Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Philippine Constitution

Uploaded by

Sarabeth Silver Macapagao0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views11 pagescase digest

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentcase digest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views11 pagesPhilippine Constitution

Uploaded by

Sarabeth Silver Macapagaocase digest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

G.R. No.

83820 May 25, 1990

JOSE B. AZNAR (as Provincial Chairman of PDP Laban in Cebu), petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON

ELECTIONS and EMILIO MARIO RENNER OSMEA, respondents.

Ponente: J. Paras

Facts:

Private respondent Emilio "Lito" Osmea filed his certificate of candidacy with the COMELEC for

the position of Provincial Governor of Cebu Province in the January 18, 1988 local elections. On

January 22, 1988, the Cebu PDP-Laban Provincial Council (Cebu-PDP Laban, for short), as

represented by petitioner Jose B. Aznar in his capacity as its incumbent Provincial Chairman,

filed with the COMELEC a petition for the disqualification of private respondent on the ground

that he is allegedly not a Filipino citizen, being a citizen of the United States of America.

On January 27, 1988, petitioner filed a Formal Manifestation submitting a Certificate issued by

the then Immigration and Deportation Commissioner Miriam Defensor Santiago certifying that

private respondent is an American and is a holder of Alien Certificate of Registration (ACR) No.

B-21448 and Immigrant Certificate of Residence (ICR) No. 133911, issued at Manila on March

27 and 28, 1958, respectively. (Annex "B-1").

The petitioner also filed a Supplemental Urgent Ex-Parte Motion for the Issuance of a

Temporary Restraining Order to temporarily enjoin the Cebu Provincial Board of Canvassers

from tabulating/canvassing the votes cast in favor of private respondent and proclaiming him

until the final resolution of the main petition.Thus, on January 28, 1988, the COMELEC en banc

resolved to order the Board to continue canvassing but to suspend the proclamation.

Private respondent, on the other hand, maintained that he is a Filipino citizen, alleging: that he

is the legitimate child of Dr. Emilio D. Osmea, a Filipino and son of the late President Sergio

Osmea, Sr.; that he is a holder of a valid and subsisting Philippine Passport No. 0855103 issued

on March 25, 1987; that he has been continuously residing in the Philippines since birth and has

not gone out of the country for more than six months; and that he has been a registered voter

in the Philippines since 1965.

On March 3, 1988, COMELEC (First Division) directed the Board of Canvassers to proclaim the

winning candidates. Having obtained the highest number of votes, private respondent was

proclaimed the Provincial Governor of Cebu. Thereafter, on June 11, 1988, COMELEC (First

Division) dismissed the petition for disqualification for not having been timely filed and for lack

of sufficient proof that private respondent is not a Filipino citizen. Hence, the present petition

for certiorari.

Issue: won the respondent is an alien

Ruling:

The records show that private respondent filed his certificate of candidacy on November 19,

1987 and that the petitioner filed its petition for disqualification of said private respondent on

January 22, 1988. Since the petition for disqualification was filed beyond the twenty five-day

period required in Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, it is clear that said petition was

filed out of time.

However, We deem it is a matter of public interest to ascertain the respondent's citizenship and

qualification to hold the public office to which he has been proclaimed elected. There is enough

basis for us to rule directly on the merits of the case, as the COMELEC did below.

Petitioner's contention that private respondent is not a Filipino citizen and, therefore,

disqualified from running for and being elected to the office of Provincial Governor of Cebu, is

not supported by substantial and convincing evidence.

In the proceedings before the COMELEC, the petitioner failed to present direct proof that

private respondent had lost his Filipino citizenship by any of the modes provided for under C.A.

No. 63. Among others, these are: (1) by naturalization in a foreign country; (2) by express

renunciation of citizenship; and (3) by subscribing to an oath of allegiance to support the

Constitution or laws of a foreign country. From the evidence, it is clear that private respondent

Osmea did not lose his Philippine citizenship by any of the three mentioned hereinabove or by

any other mode of losing Philippine citizenship.

Parenthetically, the statement in the 1987 Constitution that "dual allegiance of citizens is

inimical to the national interest and shall be dealt with by law"(Art. IV, Sec. 5) has no

retroactive effect. And while it is true that even before the 1987 Constitution, Our country had

already frowned upon the concept of dual citizenship or allegiance, the fact is it actually existed.

Be it noted further that under the aforecited proviso, the effect of such dual citizenship or

allegiance shall be dealt with by a future law. Said law has not yet been enacted.

WHEREFORE, the petition for certiorari is hereby DISMISSED and the Resolution of the

COMELEC is hereby AFFIRMED.

G.R. No. L-83882 January 24, 1989

IN RE PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS OF WILLIE YU, petitioner,

vs. MIRIAM DEFENSOR-SANTIAGO, BIENVENIDO P. ALANO, JR., MAJOR PABALAN, DELEO

HERNANDEZ, BLODDY HERNANDEZ, BENNY REYES and JUN ESPIRITU SANTO, respondent.

Ponente: J. Padilla

Facts:

In the case at bar, herein petitioner, despite his naturalization as a Philippine citizen, applied

and renewed his Portuguese passport. Moreover, while still a citizen of the Philippines,

petitioner also declared his nationality as Portuguese in commercial documents he signed.

Issue: Whether or not the acts of applying for a foreign passport and declaration of foreign

nationality in commercial documents, constitute an expressrenunciation of ones Philippine

citizenship acquired through naturalization.

Ruling:

While still a citizen of the Philippineswho had renounced, upon his naturalization, "absolutely

and forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince,potentate, state or sovereignty" and

pledged to "maintain true faith and allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines," 19 he

declared his nationality as Portuguese in commercialdocuments he signed, specifically, the

Companies registry of Tai Shun Estate Ltd. 20 filed in Hongkong sometime in April 1980.

To the mind of the Court, the foregoing acts considered together constitute an express

renunciation of petitioner's Philippine citizenship acquired through naturalization.

Petitioner, with full knowledge, and legal capacity, after having renounced Portuguese

citizenship upon naturalization as a Philippine citizen 22 resumed or reacquired his prior status

as a Portuguese citizen, applied for a renewal of his Portuguese passport 23 and represented

himself as such in official documents even after he had become a naturalized Philippine citizen.

Such resumption or reacquisition of Portuguese citizenship is grossly inconsistent with his

maintenance of Philippine citizenship.

ANTONIO BENGSON III, petitioner, vs . HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL and

TEODORO C. CRUZ, respondents

[G.R. No. 142840. May 7, 2001

Ponente: J. Kapunan

Facts:

Respondent Cruz was a natural-born citizen of the Philippines. He was born in San Clemente,

Tarlac, on April 27, 1960, of Filipino parents. The fundamental law then applicable was the 1935

Constitution.On November 5, 1985, however, respondent Cruz enlisted in the United States

Marine Corps and, without the consent of the Republic of the Philippines, took an oath of

allegiance to the United States. As a consequence, he lost his Filipino citizenship for under

Commonwealth Act No. 63, Section 1(4), a Filipino citizen may lose his citizenship by, among

others, "rendering service to or accepting commission in the armed forces of a foreign country."

On March 17, 1994, respondent Cruz reacquired his Philippine citizenship through repatriation

under Republic Act No. 2630. [3] He ran for and was elected as the Representative of the

Second District of Pangasinan in the May 11, 1998 elections. He won by a convincing margin of

26,671 votes over petitioner Antonio Bengson III, who was then running for reelection.

Subsequently, petitioner filed a case for Quo Warranto Ad Cautelam with respondent House of

Representatives Electoral Tribunal (HRET) claiming that respondent Cruz was not qualified to

become a member of the House of Representatives since he is not a natural-born citizen as

required under Article VI, Section 6 of the Constitution.

On March 2, 2000, the HRET rendered its decision [5] dismissing the petition for quowarranto

and declaring respondent Cruz the duly elected Representative of the Second District of

Pangasinan in the May 1998 elections. The HRET likewise denied petitioner's motion for

reconsideration of the decision in its resolution dated April 27, 2000. [6] Petitioner thus filed

the present petition for certiorari.

Issue: WON Cruz, a natural-born Filipino who became an American citizen, can still be

considered a natural-born Filipino upon his reacquisition of Philippine citizenship.

Ruling:

As respondent Cruz was not required by law to go through naturalization proceedings in order

to reacquire his citizenship, he is perforce a natural- born Filipino. As such, he possessed all the

necessary qualifications to be elected as member of the House of Representatives.

A final point. The HRET has been empowered by the Constitution to be the "sole judge" of all

contests relating to the election, returns, and qualifications of the members of the House. [29]

The Court's jurisdiction over the HRET is merely to check "whether or not there has been a

grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction" on the part of the latter.

[30] In the absence thereof, there is no occasion for the Court to exercise its corrective power

and annul the decision of the HRET nor to substitute the Court's judgment for that of the latter

for the simple reason that it is not the office of a petition for certiorari to inquire into the

correctness of the assailed decision. [31] There is no such showing of grave abuse of discretion

in this case.

Said provision of law reads: Section 1. How citizenship may be lost. -- A Filipino citizen may lose

his citizenship in any of the following ways and/or events:

x x x

(4) By rendering services to, or accepting commission in, the armed forces of a foreign country:

Provided, That the rendering of service to, or the acceptance of such commission in, the armed

forces of a foreign country, and the taking of an oath of allegiance incident thereto, with the

consent of the Republic of the Philippines, shall not divest a Filipino of his Philippine citizenship

if either of the following circumstances is present:

(a) The Republic of the Philippines has a defensive and/or offensive pact of alliance with said

foreign country; or

(b) The said foreign country maintains armed forces on Philippine territory with the consent of

the Republic of the Philippines: Provided, That the Filipino citizen concerned, at the time of

rendering said service, or acceptance of said commission, and taking the oath of allegiance

incident thereto, states that he does so only in connection with his service to said foreign

country; And provided, finally, That any Filipino citizen who is rendering service to, or is

commissioned in, the armed forces of a foreign country under any of the circumstances

mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b), shall not be permitted to participate nor vote in any election

of the Republic of the Philippines during the period of his service to, or commission in, the

armed forces of said country. Upon his discharge from the service of the said foreign country,

he shall be automaticallyentitled to the full enjoyment of his civil and political rights as a

Filipino citizen x x x.

To be naturalized, an applicant has to prove that he possesses all the qualifications 12] and

none of the disqualifications [13] provided by law to become a Filipino citizen. The decision

granting Philippine citizenship becomes executory only after two (2) years from its

promulgation when the court is satisfied that during thei ntervening period, the applicant has (1)

not left the Philippines; (2) has dedicated himself to a lawful calling or profession; (3) has not

been convicted of any offense or violation of Government promulgated rules; or (4)

committedany act prejudicial to the interest of the nation or contrary to any Government

announced policies.

[ 14] Filipino citizens who have lost their citizenship may however reacquire the same in the

manner provided by law. Commonwealth Act. No. 63 (C.A. No. 63), enumerates the three

modes by which Philippine citizenship may be reacquired by a former citizen: (1) by

naturalization, (2) by repatriation, and (3) by direct act of Congress.

Naturalization is a mode for both acquisition and reacquisition of Philippine citizenship.

Repatriation, on the other hand, may be had under various statutes by those who lost their

citizenship due to: (1) desertion of the armed forces; [19] (2) service in the armed forces of the

allied forces in World War II; [20] (3) service in the Armed Forces of the United States at any

other time; [21] (4) marriage of a Filipino woman to an alien; [22] and (5) political and economic

necessity. 23]

As distinguished from the lengthy process of naturalization, repatriation simply consists of the

taking of an oath of allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines and registering said oath in the

Local Civil Registry of the place where the person concerned resides or last resided.

Repatriation results in the recovery of the original nationality.

R.A. No. 2630, which provides:

Section 1. Any person who had lost his Philippine citizenship by rendering service to, or

accepting commission in, the Armed Forces of the United States, or after separation from the

Armed Forces of the United States, acquired United States citizenship, may reacquire Philippine

citizenship by taking an oath of allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines and registering the

same with Local Civil Registry in the place where he resides or last resided in the Philippines.

The said oath of allegiance shall contain a renunciation of any other citizenship.

[G.R. No. 132244. September 14, 1999]

GERARDO ANGAT, petitioner, vs. REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondent.

Ponente: J. Vitug

Facts:

Petitioner Gerardo Angat was a natural born citizen of the Philippines until he lost his

citizenship by naturalization in the United States of America. Now residing at No. 69 New York

Street, Provident Village, Marikina City, Angat filed on 11 March 1996 before the RTC of

Marikina City, Branch 272, a petition to regain his status as a citizen of the Philippines under

Commonwealth Act No. 63, Republic Act No. 965 and Republic Act No. 2630 (docketed as N-96-

03-MK).

He has resided in the Philippines at least six months immediately preceding the date of this

petition, to wit: since 1991. He has conducted himself in a proper and irreproachable manner

during the entire period of his residence in the Philippines, in his relations with the constituted

government as well as with the community in which he is living.It is his intention to reacquire

Philippine citizenship and to renounce absolutely and forever all allegiance and fidelity to any

foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, and particularly to the United State of America

to which at this time he is a citizen.

On 13 June 1996, petitioner sought to be allowed to take his oath of allegiance to the Republic

of the Philippines pursuant to R.A. 8171 . The motion was denied by the trial judge in his order

of 12 July 1996. Another motion filed by petitioner on 13 August 1996 to have the denial

reconsidered was found to be meritorious by the court a quo in an order, dated 20 September

1996, which stated, among other things, that - A close scrutiny of R.A. 8171 shows that

petitioner is entitled to the benefits of the said law considering that herein petitioner is a

natural born Filipino citizen who lost his citizenship by naturalization in a foreign country. The

petition and motion of the petitioner to take his oath of allegiance to the Republic of the

Philippines likewise show that the petitioner possesses all the qualifications and none of the

disqualifications under R.A. 8171.

FACTS:

Petitioner Gerardo Angat was a natural born citizen of the Philippines until he lost his

citizenship by naturalization in the United States of America. On 11 March 1996, he filed before

the RTC of Marikina City, Branch 272, a petition to regain his Status as a citizen of the

Philippines under Commonwealth Act No. 63, Republic Act No. 965 and Republic Act No. 2630.

The case was thereafter set for initial hearing.

On 13 June 1996, petitioner sought to be allowed to take his oath of allegiance to the Republic

of the Philippines pursuant to R.A. 8171. The motion was initially denied by the trial judge but

after a motion for reconsideration, it was granted. The petitioner was ordered to take his oath

of allegiance pursuant to R.A. 8171. After taking his oath of allegiance, the trial court issued an

order repatriating petitioner and declaring him as citizen of the Philippines pursuant to Republic

Act No. 8171. The Bureau of Immigration was ordered to cancel his alien certificate of

registration and issue the certificate of identification as Filipino citizen. On 19 March 1997, the

Office of the Solicitor General filed a Manifestation and Motion (virtually a motion for

reconsideration) asserting that the petition itself should have been dismissed by the court a

quo for lack of jurisdiction because the proper forum for it was the Special Committee on

Naturalization consistently with Administrative Order No. 285 ("AO 285"), dated 22 August

1996, issued by President Fidel V. Ramos. AO 285 had tasked the Special Committee on

Naturalization to be the implementing agency of R.A 8171. The trial court granted the motion

and dismissed the petition. Petitioner appealed contending that the RTC seriously erred in

dismissing the petition by giving retroactive effect to Administrative Order No. 285, absent a

provision on Retroactive Application.

ISSUES:

WON Court erred in dismissing the petition by giving retroactive effect to AO 285, absent a

provision on Retroactive Application

HELD:

No. Under Section 1 of Presidential Decree ("P.D.") No. 725, 8 dated 05 June 1975, amending

Commonwealth Act No. 63, an application for repatriation could be filed by Filipino women

who lost their Philippine citizenship by marriage to aliens, as well as by natural born Filipinos

who lost their Philippine citizenship, with the Special Committee on Naturalization. The

committee, chaired by the Solicitor General with the Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs and the

Director of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency asthe other members, was created

pursuant to Letter of instruction ("LOI") No. 270, dated 11 April 1975, as amended by LOI No.

283 and LOI No. 491 issued, respectively, on 04 June 1975 and on 29 December 1976. Although

the agency was deactivated by virtue of President Corazon C. Aquino's Memorandum of 27

March 1987, it was not however, abrogated. In Frivaldo vs. Commission on Elections, 9 the

Court observed that the aforedated memorandum of President Aquino had merely directed the

Special Committee on Naturalization "to cease and desist from undertaking any and all

proceedings . . . under Letter of Instruction ("LOI") 270." 10 The Court elaborated: This

memorandum dated March 27, 1987 cannot by any stretch of legal hermeneutics be construed

as a law sanctioning or authorizing a repeal of P.D. No. 725. Laws are repealed only by

subsequent ones and a repeal may be express or implied. It is obvious that no express repeal

was made because then President Aquino in her memorandum-based on the copy furnished us

by Lee-did not categorically and/or impliedly state that P.D. 725 was being repealed or was

being rendered without any legal effect. In fact, she did not even mention it specifically by its

number or text. On the other hand, it is a basic rule of statutory construction that repeals by

implication are not favored. An implied repeal will not be allowed "unless it is convincingly

andunambiguously demonstrated that the two laws are clear repugnant and patently

inconsistent that they cannot co-exist."

Indeed, the Committee was reactivated on 08 June 1995 ; hence, when petitioner filed his

petition on 11 March 1996, the Special Committee on Naturalization constituted pursuant to

LOI No. 270 under P.D. No. 725 was in place. Administrative Order 285, promulgated on 22

August 1996 relative to R.A. No. 8171, in effect, was merely then a confirmatory issuance.

The Office of the Solicitor General was right in maintaining that Angat's petition should have

been filed with the Committee, aforesaid, and not with the RTC which had no jurisdiction

thereover. The court's order of 04 October 1996 was thereby null and void, and it did not

acquire finality nor could be a source of right on the part of petitioner. It should also be

noteworthy that the was one for repatriation, and it was thus incorrect for petitioner to initially

invoke Republic Act No. 965 and R.A. No. 2630 since these laws could only apply to persons

who had lost their citizenship by rendering service to, or accepting commission in, the armed

forces of an allied foreign country or the armed forces of the United States of America, a factual

matter not alleged in the petition, Parenthetically, under these statutes,the person desiring to

re-acquire Philippine citizenship would not even be required to file a petition in court , and all

that he had to do was to take an oath of allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines and to

register that fact with the civil registry in the place of his residence or where he had last resided

in the Philippines.

[G.R. No. 161434. March 3, 2004]

MARIA JEANETTE C. TECSON and FELIX B. DESIDERIO, JR., petitioners, vs. The COMMISSION ON

ELECTIONS, RONALD ALLAN KELLY POE (a.k.a. FERNANDO POE, JR.) and VICTORINO X. FORNIER,

respondents.

Ponente: J. Vitug

Petitioners sought for respondent Poes disqualification in the presidential elections for having

allegedly misrepresented material facts in his (Poes) certificate of candidacy by claiming that

he is a natural Filipino citizen despite his parents both being foreigners. Comelec dismissed the

petition, holding that Poe was a Filipino Citizen. Petitioners assail the jurisdiction of the

Comelec, contending that only the Supreme Court may resolve the basic issue on the case

under Article VII, Section 4, paragraph 7, of the 1987 Constitution.

Issue:

Whether or not it is the Supreme Court which had jurisdiction.

Whether or not Comelec committed grave abuse of discretion in holding that Poe was a Filipino

citizen.

Ruling:

The Supreme Court had no jurisdiction on questions regarding qualification of a candidate for

the presidency or vice-presidency before the elections are held. "Rules of the Presidential

Electoral Tribunal" in connection with Section 4, paragraph 7, of the 1987 Constitution, refers to

contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the "President" or "Vice-

President", of the Philippines which the Supreme Court may take cognizance, and not of

"candidates" for President or Vice-President before the elections. Comelec committed no grave

abuse of discretion in holding Poe as a Filipino Citizen. The 1935 Constitution on Citizenship, the

prevailing fundamental law on respondents birth, provided that among the citizens of the

Philippines are "those whose fathers are citizens of the Philippines."

Tracing respondents paternal lineage, his grandfather Lorenzo, as evidenced by the latters

death certificate was identified as a Filipino Citizen. His citizenship was also drawn from the

presumption that having died in 1954 at the age of 84, Lorenzo would have been born in 1980.

In the absence of any other evidence, Lorenzos place of residence upon his death in 1954 was

presumed to be the place of residence prior his death, such that Lorenzo Pou would have

benefited from the "en masse Filipinization" that the Philippine Bill had effected in 1902. Being

so, Lorenzos citizenship would have extended to his son, Allan--- respondents

father.Respondent, having been acknowledged as Allans son to Bessie, though an American

citizen, was a Filipino citizen by virtue of paternal filiation as evidenced by the respondents

birth certificate. The 1935 Constitution on citizenship did not make a distinction on the

legitimacy or illegitimacy of the child, thus, the allegation of bigamous marriage and the

allegation that respondent was born only before the assailed marriage had no bearing on

respondents citizenship in view of the established paternal filiation evidenced by the public

documents presented.

But while the totality of the evidence may not establish conclusively that respondent FPJ is a

natural-born citizen of the Philippines, the evidence on hand still would preponderate in his

favor enough to hold that he cannot be held guilty of having made a material misrepresentation

in his certificate of candidacy in violation of Section 78, in relation to Section 74 of the Omnibus

Election Code.

You might also like

- 03-Security of Tenure PDFDocument2 pages03-Security of Tenure PDFSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Handout 04-Speech of Dean Abad Re DO No. 3Document10 pagesHandout 04-Speech of Dean Abad Re DO No. 3emerbmartinNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument27 pagesPDFSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Provisional Remedies Full TextDocument10 pagesProvisional Remedies Full TextSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- WHO HIV 2016.20 EngDocument68 pagesWHO HIV 2016.20 EngConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

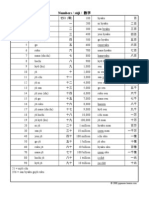

- KanjiDocument3 pagesKanjiSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 5, Number 19Document2 pagesAssignment 5, Number 19ConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: How Many Words?Document2 pagesVocabulary: How Many Words?Sarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Japanese Numbers PDFDocument1 pageJapanese Numbers PDFchvsuneelNo ratings yet

- Spec Pro Assigned CasesDocument7 pagesSpec Pro Assigned CasesConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

- LP CitizenshipDocument13 pagesLP CitizenshipSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Contracts Full CasesDocument331 pagesContracts Full CasesSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court Rules on Abrogation of Spanish Penal Code ArticleDocument18 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court Rules on Abrogation of Spanish Penal Code ArticleSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- LP CitizenshipDocument13 pagesLP CitizenshipSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Canon 14 Ledesma vs. ClimacoDocument1 pageCanon 14 Ledesma vs. ClimacoSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Canon 6Document4 pagesCanon 6Sarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestSarabeth Silver MacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Obama Ballot Illinois Jackson Complaint PagesDocument283 pagesObama Ballot Illinois Jackson Complaint PagesPamela BarnettNo ratings yet

- Crim Law 2 - Up Notes PDFDocument102 pagesCrim Law 2 - Up Notes PDFMaitaNo ratings yet

- 3C Laurel PT 1Document13 pages3C Laurel PT 1John Paulo Genesis AquinoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law II Digest SummariesDocument206 pagesCriminal Law II Digest SummariesMustapha AmpatuanNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Misa: Treason Prosecution During Japanese OccupationDocument3 pagesLaurel vs. Misa: Treason Prosecution During Japanese OccupationJohnson YaplinNo ratings yet

- Philippine Law Reviewers Criminal Law Book 2 Title OneDocument14 pagesPhilippine Law Reviewers Criminal Law Book 2 Title OneShaira Mae CuevillasNo ratings yet

- Valles Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesValles Vs Comelectimothymarkmaderazo100% (1)

- Petition To Deny Due CourseDocument9 pagesPetition To Deny Due CourseBill Diaz100% (1)

- B11. AASJS V Datumanong - DIGESTDocument2 pagesB11. AASJS V Datumanong - DIGESTChap ChoyNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Book 2: Title One I. Crimes Against National SecurityDocument13 pagesCriminal Law Book 2: Title One I. Crimes Against National SecurityDaphne Dianne MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Notarial Tribunal For The United States of America Public NoticeDocument7 pagesThe Notarial Tribunal For The United States of America Public NoticeGovernment of The United States of America67% (3)

- Are Approved, Taking The Necessary Oath of Allegiance To The Republic of TheDocument6 pagesAre Approved, Taking The Necessary Oath of Allegiance To The Republic of TheKyle BanceNo ratings yet

- Tanzania Citizenship Act 1995 PDFDocument19 pagesTanzania Citizenship Act 1995 PDFNerson KanyikiNo ratings yet

- Art. IV & V Case Digests and Bar QuestionsDocument7 pagesArt. IV & V Case Digests and Bar QuestionsClaire Culminas100% (1)

- Philippine citizenship law allows dual citizenshipDocument9 pagesPhilippine citizenship law allows dual citizenshipriaheartsNo ratings yet

- Bengson vs. CruzDocument9 pagesBengson vs. CruzWilfredNo ratings yet

- 15-Maquiling v. COMELEC G.R. No. 195649 April 16, 2013Document16 pages15-Maquiling v. COMELEC G.R. No. 195649 April 16, 2013Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- RA 9225 Dual CitizenshipDocument4 pagesRA 9225 Dual CitizenshipmarthaNo ratings yet

- Article 114-117 of The RPCDocument4 pagesArticle 114-117 of The RPCRALPH CORTESNo ratings yet

- Wong Kim Ark US V 169 US 649 1898 STATEMENT of The Case by Thomas D Riordan Atty For Respondent WKADocument14 pagesWong Kim Ark US V 169 US 649 1898 STATEMENT of The Case by Thomas D Riordan Atty For Respondent WKANative Born CitizenNo ratings yet

- Article IV and VDocument12 pagesArticle IV and VNorienne Teodoro0% (1)

- FT Labo, Jr. v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 86564, August 1, 1989)Document11 pagesFT Labo, Jr. v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 86564, August 1, 1989)1D OFFICIALDRIVENo ratings yet

- Citizenship Just The Facts - ReadingDocument3 pagesCitizenship Just The Facts - Readingmaddycad28No ratings yet

- 9 ROMEL ARNADO v. COMELEC CAPITAN GR No. 210164 18 August 2015Document27 pages9 ROMEL ARNADO v. COMELEC CAPITAN GR No. 210164 18 August 2015Jaime Rariza Jr.No ratings yet

- Laurel Vs MisaDocument5 pagesLaurel Vs MisaAj Guadalupe de MataNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument28 pagesReportRico T. MusongNo ratings yet

- What Is The Church by A.T. JonesDocument19 pagesWhat Is The Church by A.T. JonesTrent Riffin Wilde100% (4)

- D2-Oath of AllegianceDocument1 pageD2-Oath of AllegiancejameelNo ratings yet

- Crime 2 TableDocument120 pagesCrime 2 TableDaNiel Kien GauDielNo ratings yet

- Calilung Vs DatumanongDocument2 pagesCalilung Vs DatumanongInez Monika Carreon PadaoNo ratings yet