Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Harvard Theological Review

Uploaded by

Pablo CarreñoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Harvard Theological Review

Uploaded by

Pablo CarreñoCopyright:

Available Formats

Harvard Theological Review

http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR

Additional services for Harvard Theological

Review:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

The Gospel of Jesus's Wife: A Preliminary

Paleographical Assessment

Malcolm Choat

Harvard Theological Review / Volume 107 / Issue 02 / April 2014, pp 160 - 162

DOI: 10.1017/S0017816014000145, Published online: 10 April 2014

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0017816014000145

How to cite this article:

Malcolm Choat (2014). The Gospel of Jesus's Wife: A Preliminary Paleographical

Assessment . Harvard Theological Review, 107, pp 160-162 doi:10.1017/

S0017816014000145

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 200.121.41.169 on 17 Apr 2014

HTR 107:2 (2014) 16071

The Gospel of Jesuss Wife: A Preliminary Paleographical

Assessment

*

Malcolm Choat

Macquarie University

It is the simple truth that paleographical analysis alone is sometimes not suffcient

to settle questions of authenticity.

1

In the present case, while further conservation

is required for a fnal judgment on some issues,

2

I have not found a smoking gun

that indicates beyond doubt that the text was not written in antiquity, but nor can

such an examination prove that it is genuine. I do, however, believe the present case

is less straightforward than some proponents of forgery have assumed.

3

I confne

myself here to a few observations.

*

The remarks below are based on autopsy of the papyrus on November 14 and 15, 2012, at the

invitation both of Professor King and of Professors Madigan and Levenson in their capacity as editors

of the Harvard Theological Review, and on high defnition images subsequently provided to me.

1

Witness most obviously the continuing controversy over the Artemidorus papyrus. I do not

take any account here of analysis of the textual content or scientifc testing, both of which are also

required to make a judgment on authenticity.

2

Specifcally, correct positioning of the dislodged fbers at the beginning of lines 25 on the

front; see further below.

3

As the discussion concerning this fragment has taken place almost exclusively online or via the

media since it was made public, I respond here inter alia to points that have been raised by various

commentators both in conversation (which I have not attributed) and in fora such as blogs: the lat-

ter include Peter Head, More questions on Jesus Wife Fragment, Evangelical Textual Criticism

[blog], October 3, 2012, http://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/more-questions-

on-jesus-wife-fragment.html; Hugo Lundhaug and Alin Suciu, On the So-Called Gospel of Jesuss

Wife: Some Preliminary Thoughts by Hugo Lundhaug and Alin Suciu, Patristics, Apocrypha,

Coptic Literature and Manuscripts [blog], September 26, 2012, http://alinsuciu.com/2012/09/26/

on-the-so-called-gospel-of-jesuss-wife-some-preliminary-thoughts-by-hugo-lundhaug-and-alin-suciu/;

and the remarks of Christian Askeland on the fragment (JesusWife, video clip, 9:43, September

28, 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7LtRVtLXpkQ). See also Michael Peppard, Gospel

of Jesus WifeOne year later, dotCommonweal [blog], December 5, 2013, https://www.com-

monwealmagazine.org/blog/gospel-jesus-wife-one-year-later. I should emphasize (with apologies

to others who have contributed paleographical observations) that this list is not exhaustive and that

I do not respond here to every point made in these blogs.

REPORTS OF EXPERT ANALYSIS AND TESTING 161

The hand suggests an informal context of production.

4

The handwriting is

not similar to formal literary productions of any period and should be compared

rather to documentary or paraliterary texts (though it does not closely resemble

typical fourth-century Coptic documentary hands).

5

While I cannot adduce an

exact parallel, I am inclined to compare paraliterary productions such as magical

or educational texts.

6

The way the same letter is formed sometimes varies.

7

Thin trails of ink at the

bottom of many letters, multiple thin lines instead of one stroke,

8

and the forked

ends of some letters could suggest the use of a brush, rather then a pen: one may

compare Ptolemaic-period Greek documents written with a brush.

9

The brush had

largely ceased to be used by the Roman period

10

and should not be encountered in

this context. However, one can observe analogous phenomena in later texts that are

neither presumed to have been made by a brush nor suspected of being forgeries.

11

I have been unable to confrm that there is any ink on the lower layer of fbers

in the start of lines 25 or inside the damaged area of what has been read as the

4

One might also note in this connection that the fact that there are six lines of text on the back

and eight on the front is not uncommon in less formal contexts.

5

Now well attested: see P.Lond. 6.192022, P.Ryl.Copt. 268276, and the documentary papyri

published in Coptic Documentary Texts from Kellis: P. Kell.V (P. Kell. Copt. 1052; O. Kell. Copt.

12) (ed. Iain Gardner, Anthony Alcock, and Wolf-Peter Funk; Dakhleh Oasis Project 9; Oxford:

Oxbow, 1999). For the abbreviations for papyrus volumes used here, see Roger S. Bagnall et al.,

Checklist of Greek, Latin, Demotic and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca and Tablets, June 1, 2011, http://

scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/papyrus/texts/clist.html.

6

See, e.g., the irregular and informal script found in magical texts such as P.Bad. 5.126 (VI

VIII), P.Mich. inv. 594r (VIVII), or P.Kln inv 20806r (IVVIII) and, among educational texts,

papyri such as such as P.Rain.UnterrichtKopt. 15 (VIII/IX?), 268 (VII), or 279 (XXI). I cite these

papyri here only as examples of less formal hands, and I would not compare the hand of the GJW

papyrus specifcally to them, especially not for dating purposes.

7

Sometimes letters are made very chunkily, at other times not: compare, e.g., the tau of

in 1 with that in in 2.

8

See, e.g., the nu of in 1; the fnal pi in 1; the ti in 1; and the frst mu of

in 2. See also especially the frst epsilon (?) and the nu of in 6; many other examples

could be cited.

9

E.g., P.Cair.Zen. 2.59243r and P.Mich. 1.29. On the use of the brush in Ptolemaic texts, see

William J. Tait, Rush and Reed: The Pens of Egyptian and Greek Scribes, in Proceedings of the

XVIII International Congress of Papyrology, Athens, 2531 May 1986 (ed. Basil G. Mandilaras;

2 vols.; Athens: Greek Papyrological Society, 1988) 2:47781; Willy Clarysse, Egyptian Scribes

Writing Greek, ChrEg 68 (1993) 185201; Joshua D. Sosin and Joseph G. Manning, Palaeography

and Bilingualism: P.Duk. inv. 320 and 675, ChrEg 78 (2003) 20210.

10

Mark Depauw, The Demotic Letter: A Study of Epistolographic Scribal Traditions against Their

Intra- and Intercultural Background (Demotische Studien 14; Sommerhausen: Zauzich, 2006) 7677.

11

See, e.g., P.Rain.UnterrichtKopt. 279, an educational text from the 10

th

or 11

th

cent. C.E.:

the editor (Monika Hasitzka) remarks simply Breiter Kalamos in her introduction to the edition

(compare the remarks on the GJW papyrus of R. S. Bagnall quoted by King: the pen itself may

have been blunt and not holding the ink well). For an image of this text, see the Tafelband for

P.Rain.UnterrichtKopt. (in which it is Taf. 100) or search for P.Rain.UnterrichtKopt. 279 on the

website of the Austrian National Library Papyrus Collection: http://aleph.onb.ac.at/F?func=fle&fle_

name=login&local_base=ONB08.

162 HARVARD THEOLOGICAL REVIEW

second mu of in line 3 (which would surely indicate a modern forgery).

Further conservation of the papyrus is required to confrm this beyond doubt. It

is, however, clear that some issues that have been brought forward as evidence of

forgery are apparent only on the digital images that were originally made available:

this primarily concerns cases in which holes in the papyrus appear to be ink in

the image

12

and where pooling of ink is not apparent on the papyrus itself.

13

The

text in line 7 is also clearly under the blob of foreign matter (some type of

wax?).

14

The oblique stroke before in 4 is more likely the remains of

a letter than a mark of punctuation.

15

One can also note that the lack of ink on the

left two-thirds of the back is clearly caused by the loss of most of the upper

layer of fbers at this point and that, while the top edge of the papyrus does give

the appearance of having been cut, not broken,

16

such a clean straight break is not

unknown in genuine papyri.

17

Overall, if the general appearance of the papyrus prompts some suspicion, it is

diffcult to falsify by a strictly paleographical examination. This should not be taken

as proof that the papyrus is genuine, simply that its handwriting and the manner in

which it has been written do not provide defnitive grounds for proving otherwise.

Characterization of the Chemical Nature of the Black Ink in the

Manuscript of The Gospel of Jesuss Wife through Micro-Raman

Spectroscopy

James T. Yardley

Department of Electrical Engineering, Columbia University

Alexis Hagadorn

Conservator and Head of the Conservation Program, Columbia University Libraries

Brief Summary

Date of study: March 1112, 2013

A research team at Columbia University consisting of Professor James T.

Yardley of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Alexis Hagadorn, Head

of Conservation, Columbia University Libraries, with the support of Dr. David

12

See, e.g., the frst alpha of in line 3, where there is a tiny hole in the papyrus at the

bottom right of the alpha.

13

E.g., to the bottom right of the frst alpha of in 3 and in the diagonal stroke before

(4), where I can see neither the hole that was noted in the draft edition, nor ink pooling around it.

14

See especially the frst of .

15

Note that the scribe varies letter forms elsewhere (compare the upsila in 4 and 5 [,

] with that in 6 []), and something like ] or ] ] might be considered.

16

On the front, there appear to be no remains of a line above line 1: a trace of ink on a

partially detached fber above the second alpha of probably comes from the alpha itself.

17

Such cuts are commonly made in modern times (e.g. to cut up a text to sell to different buy-

ers), but similar breaks also occur in papyri discovered in archaeological context.

You might also like

- Asser's Life of King Alfred, Together with the Annals of Saint NeotsFrom EverandAsser's Life of King Alfred, Together with the Annals of Saint NeotsNo ratings yet

- The Discovery of The Pentateuch of The Syro-HexaplaDocument3 pagesThe Discovery of The Pentateuch of The Syro-HexaplaJean-Charles CoulonNo ratings yet

- The Sin of Sloth: Acedia in Medieval Thought and LiteratureFrom EverandThe Sin of Sloth: Acedia in Medieval Thought and LiteratureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Cambridge University Press The Classical AssociationDocument6 pagesCambridge University Press The Classical AssociationPablo MizrajiNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary of The Greek Testament Moulton MilliganDocument737 pagesVocabulary of The Greek Testament Moulton MilliganJason Jones100% (1)

- Family (Pi) and The Codex Alexandrinus (Microform) - The Text According To Mark Por Silva LAKE y David VOSSDocument184 pagesFamily (Pi) and The Codex Alexandrinus (Microform) - The Text According To Mark Por Silva LAKE y David VOSSmompou88No ratings yet

- NOCK A JEA 192911 Greek Magical PapyriDocument18 pagesNOCK A JEA 192911 Greek Magical Papyriivory2011No ratings yet

- Paul and SenecaDocument193 pagesPaul and Senecadragonwarrior83100% (4)

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument15 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University PressSebastien Jones HausserNo ratings yet

- Exposito Rs Greek T 02 NicoDocument970 pagesExposito Rs Greek T 02 NicodavidhankoNo ratings yet

- Lewis, Papyrus in Classical Antiquity chpt 1 'Habitats and Translants' (1974) + some reviews)Document36 pagesLewis, Papyrus in Classical Antiquity chpt 1 'Habitats and Translants' (1974) + some reviews)luzuNo ratings yet

- Galatians Lightfoot PDFDocument395 pagesGalatians Lightfoot PDFRavi100% (1)

- Epistle To Hebrews 00 RendDocument220 pagesEpistle To Hebrews 00 RendAbigailGuido89No ratings yet

- Patristic Evidence and Textual CriticismDocument2 pagesPatristic Evidence and Textual CriticismFADI KNo ratings yet

- KIRSOPP LAKE - The Text of The Gospel in AlexandriaDocument11 pagesKIRSOPP LAKE - The Text of The Gospel in AlexandriaJorge H. Ordóñez T.No ratings yet

- Plutarch and History by PellingDocument447 pagesPlutarch and History by PellingRenatoNo ratings yet

- 14145early Medieval Glosses On Prudentius PsychomachiaDocument4 pages14145early Medieval Glosses On Prudentius PsychomachiaRodrigoNo ratings yet

- Grenfell, Hunt (Eds.) - The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 1898. Volume 01.Document336 pagesGrenfell, Hunt (Eds.) - The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 1898. Volume 01.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Dating The Oldest New Testament ManuscriptsDocument4 pagesDating The Oldest New Testament ManuscriptsRosevarte DeSouzaNo ratings yet

- Sandy ChristianPapyrus GTJDocument11 pagesSandy ChristianPapyrus GTJcirojmedNo ratings yet

- Notices of Books: Virt. 14 Are Contrasted To Show That 'There Is FarDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: Virt. 14 Are Contrasted To Show That 'There Is FarbrunojbrcursosNo ratings yet

- Gnostic Corruptions in The Critical TextsDocument37 pagesGnostic Corruptions in The Critical TextsJesus Lives50% (2)

- A Very Brief Introduction To The Critical Apparatus of The Nestle-Aland (Brent Nongbri)Document7 pagesA Very Brief Introduction To The Critical Apparatus of The Nestle-Aland (Brent Nongbri)Jaguar777xNo ratings yet

- The Classical ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Classical Reviewaristarchos76No ratings yet

- BarclayDocument7 pagesBarclayMonika Prša50% (2)

- The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and The Editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary HistoryDocument4 pagesThe Massachusetts Institute of Technology and The Editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary Historytongyi911No ratings yet

- Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics: Review of T. V. Evans and D. D. Obbink (Eds.), The Language of The PapyriDocument7 pagesPrinceton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics: Review of T. V. Evans and D. D. Obbink (Eds.), The Language of The PapyriMehboob Subhan QadiriNo ratings yet

- James The Lost Apocrypha of The Old Testament Their Titles and Fragments 1920Document140 pagesJames The Lost Apocrypha of The Old Testament Their Titles and Fragments 1920Paul Alexander100% (7)

- Gnostic Corruptions in The Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament PDFDocument34 pagesGnostic Corruptions in The Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament PDFLuis D. Mendoza Pérez0% (1)

- Wilson - An Alchemical Manuscript by Arnaldus de BruxellaDocument188 pagesWilson - An Alchemical Manuscript by Arnaldus de BruxellaRafael Marques GarciaNo ratings yet

- Kenyon - Our Bible and The Ancient Manuscripts - 1-1895Document358 pagesKenyon - Our Bible and The Ancient Manuscripts - 1-1895Bert Jan Lietaert Peerbolte91% (11)

- Cartas Marruecas, Documentos de Marruecos en Archivos Espanoles (Siglos XVI-XVII) - Jis - Eti180Document3 pagesCartas Marruecas, Documentos de Marruecos en Archivos Espanoles (Siglos XVI-XVII) - Jis - Eti180Ahmed KabilNo ratings yet

- The Age of The Fathers, Chapters in The History of The Church During The Fourth and Fifth Centuries Vol. 1, W. Bright. 1903Document564 pagesThe Age of The Fathers, Chapters in The History of The Church During The Fourth and Fifth Centuries Vol. 1, W. Bright. 1903David Bailey100% (1)

- Robinson. Texts and Studies: Contributions To Biblical and Patristic Literature. 1891. Volume 2, Part 3.Document234 pagesRobinson. Texts and Studies: Contributions To Biblical and Patristic Literature. 1891. Volume 2, Part 3.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- John M. Burnam, The Placidus Commentary On Statius, 1901Document46 pagesJohn M. Burnam, The Placidus Commentary On Statius, 1901José Antonio Bellido DíazNo ratings yet

- Review O'Brien, Peter T., The Epistle To The PhilippiansDocument3 pagesReview O'Brien, Peter T., The Epistle To The Philippiansgersand6852No ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument3 pagesThe University of Chicago PresspericoNo ratings yet

- Lake and Lake 1943 - The Scribe EphraimDocument7 pagesLake and Lake 1943 - The Scribe EphraimJosh AlfaroNo ratings yet

- 4th International Conference On The Science of ComputusDocument16 pages4th International Conference On The Science of Computusa1765No ratings yet

- Zeno Clean The Spears OnDocument368 pagesZeno Clean The Spears OnumitNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey, Peter - Martani, SandraDocument547 pagesJeffrey, Peter - Martani, SandraRobert-Andrei BălanNo ratings yet

- M. L. W. Laistner, The Western Church and Astrology During The Early Middle AgesDocument25 pagesM. L. W. Laistner, The Western Church and Astrology During The Early Middle Agesdiadass100% (1)

- Ancient LiteracyDocument406 pagesAncient Literacygreta_reads100% (5)

- Chrysostom's Address on Vainglory and ParentingDocument38 pagesChrysostom's Address on Vainglory and ParentingthesebooksNo ratings yet

- THE ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCI, AND ANASTASIOS THE SINAITEDocument8 pagesTHE ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCI, AND ANASTASIOS THE SINAITEderfghNo ratings yet

- [Ancient Language Resources] H. St J. Thackeray, K. C. Hanson - A Grammar of the Old Testament in Greek_ According to the Septuagint_ Introduction, Orthography, and Accidence Volume 1(1909, Wipf & Stock Publishers.pdfDocument344 pages[Ancient Language Resources] H. St J. Thackeray, K. C. Hanson - A Grammar of the Old Testament in Greek_ According to the Septuagint_ Introduction, Orthography, and Accidence Volume 1(1909, Wipf & Stock Publishers.pdfAnonymous b8zdpnAkhNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of The Old Testament in Greek According To The Septuagint PDFDocument344 pagesA Grammar of The Old Testament in Greek According To The Septuagint PDFDano Hernandez100% (2)

- Crum, Rez Hebbelynck U. Van LantschootDocument4 pagesCrum, Rez Hebbelynck U. Van LantschootbantockNo ratings yet

- Criticalexegetic 43 BroouoftDocument352 pagesCriticalexegetic 43 BroouoftAlexey LevchukNo ratings yet

- The Pauline Authorship of HebrewsDocument450 pagesThe Pauline Authorship of HebrewsAlex SavinNo ratings yet

- India and The Apostle ThomasDocument358 pagesIndia and The Apostle Thomas056Albin Joy 219No ratings yet

- The Apocalypse of ST John in A Syriac VerseDocument323 pagesThe Apocalypse of ST John in A Syriac VerseGaius DesdunNo ratings yet

- Montgomery, Daniel ICC 22 1927Document528 pagesMontgomery, Daniel ICC 22 1927AristogitoneNo ratings yet

- Loveday Alexander, "The Living Voice. Skepticism Towards The Written Word in Early Christian and in Graeco-Roman Texts"Document27 pagesLoveday Alexander, "The Living Voice. Skepticism Towards The Written Word in Early Christian and in Graeco-Roman Texts"JonathanNo ratings yet

- Roger Casement - The Crime Against Europe (The Project Gutenberg EBook)Document72 pagesRoger Casement - The Crime Against Europe (The Project Gutenberg EBook)Pablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Let's Make Science Metrics More Scientific - 464488aDocument2 pagesLet's Make Science Metrics More Scientific - 464488aPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Several Ancient Egyptian Numerals Are CoDocument12 pagesSeveral Ancient Egyptian Numerals Are CoPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Book of Thoth PDFDocument130 pagesBook of Thoth PDFamaliabogs-1No ratings yet

- Oportunity To LearnDocument32 pagesOportunity To LearnPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Mathematical AnalysisDocument31 pagesMathematical AnalysisPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- UnderstandingQualitativeResearch PDFDocument245 pagesUnderstandingQualitativeResearch PDFMarco MallamaciNo ratings yet

- QUEEN NITOCRIS: Ruler of Ancient Egypt's Sixth DynastyDocument4 pagesQUEEN NITOCRIS: Ruler of Ancient Egypt's Sixth DynastyPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Early history of Neanderthals and Denisovans revealed through statistical analysis of genetic dataDocument6 pagesEarly history of Neanderthals and Denisovans revealed through statistical analysis of genetic dataSixto Gutiérrez SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Predictive BrainsDocument12 pagesPredictive BrainsPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Assessment Test in Latin 2016-2017: Name: Country: Date: .Document1 pageAssessment Test in Latin 2016-2017: Name: Country: Date: .Pablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Michael Prince - Does Active Learning Work A Review of The Research PDFDocument10 pagesMichael Prince - Does Active Learning Work A Review of The Research PDFPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- C68147 LM PDFDocument22 pagesC68147 LM PDFJackeline Charapaqui ReluzNo ratings yet

- Social Constructionism ExplainedDocument13 pagesSocial Constructionism ExplainedPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Concept of Law - Beyond Positivism and Natural Law PDFDocument31 pagesAristotle's Concept of Law - Beyond Positivism and Natural Law PDFstephone84No ratings yet

- IMP 007 Ward - John Duns Scotus On Parts, Wholes, and Hylomorphism 2014 PDFDocument210 pagesIMP 007 Ward - John Duns Scotus On Parts, Wholes, and Hylomorphism 2014 PDFGrossetestis Studiosus100% (2)

- Evolutionary Theory for Greater Male VariabilityDocument22 pagesEvolutionary Theory for Greater Male VariabilityPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Stories From Panchatantra - Sanskrit EnglishDocument105 pagesStories From Panchatantra - Sanskrit Englishmmsingi100% (9)

- Horace Catullus and MaecenasDocument15 pagesHorace Catullus and MaecenasPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Horace Catullus and MaecenasDocument15 pagesHorace Catullus and MaecenasPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Major Philosophers and Their IdeasDocument1 pageIntroduction to Major Philosophers and Their IdeasPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- The Interpretation of Adjective-N Sequences in Spanish HeritageDocument20 pagesThe Interpretation of Adjective-N Sequences in Spanish HeritagePablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Major Philosophers and Their IdeasDocument1 pageIntroduction to Major Philosophers and Their IdeasPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Horace Catullus and Maecenas PDFDocument18 pagesHorace Catullus and Maecenas PDFPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Introduction - The Origins of Numerical AbilitiesDocument4 pagesIntroduction - The Origins of Numerical AbilitiesPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Andrea Cabel - La Caída Del Cielo o El Derrumbe de Las Dualidades Un Análisis Del Testimonio de Davi KopenawaDocument20 pagesAndrea Cabel - La Caída Del Cielo o El Derrumbe de Las Dualidades Un Análisis Del Testimonio de Davi KopenawaPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Introduction - The Origins of Numerical AbilitiesDocument4 pagesIntroduction - The Origins of Numerical AbilitiesPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Concept of Law - Beyond Positivism and Natural Law PDFDocument31 pagesAristotle's Concept of Law - Beyond Positivism and Natural Law PDFstephone84No ratings yet

- SCH 0001Document6 pagesSCH 0001Pablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Margie Martyn - Clickers in The Classroom - An Active Learning Approach PDFDocument4 pagesMargie Martyn - Clickers in The Classroom - An Active Learning Approach PDFPablo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Css LabDocument21 pagesCss LabZahid AliNo ratings yet

- Books and CatalogsDocument3 pagesBooks and CatalogsJoseph HayesNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Grammar & Writing Skills Learner's Book 1Document90 pagesCambridge Grammar & Writing Skills Learner's Book 1CiaHue LimNo ratings yet

- From The Books To The StreetsDocument31 pagesFrom The Books To The StreetsEllieNo ratings yet

- 13-LS6 DL Display and Hide Nonprinting Formatting MarksDocument16 pages13-LS6 DL Display and Hide Nonprinting Formatting MarksjosefadrilanNo ratings yet

- GR 11 MAGAZINE RUBRICDocument1 pageGR 11 MAGAZINE RUBRICLouise Katreen NimerNo ratings yet

- Terminology Related To TypographyDocument12 pagesTerminology Related To TypographyRiver PointNo ratings yet

- Paper Formatting GuidelinesDocument4 pagesPaper Formatting GuidelinesisaulNo ratings yet

- Visual Arts: With The Corresponding Contemporary ArtistsDocument20 pagesVisual Arts: With The Corresponding Contemporary ArtistsVinSynth100% (1)

- Wbsu New SyllabusDocument4 pagesWbsu New SyllabusTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- Consonant DigraphsDocument9 pagesConsonant DigraphsRossmin UdayNo ratings yet

- Jayanta MahapatraDocument1 pageJayanta MahapatraAshis Kumar MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Business Writing Workbook PDFDocument79 pagesBusiness Writing Workbook PDFAdam Diaz100% (17)

- Kaligrafi InternasionalDocument18 pagesKaligrafi Internasionaluswatun hasanahNo ratings yet

- Kanji LessonDocument5 pagesKanji LessonBivian GarciaNo ratings yet

- Surat Pernyataan Calon DosenDocument9 pagesSurat Pernyataan Calon DosenDPW PSISULTRANo ratings yet

- Businessman Hand Golden Key PowerPoint TemplatesDocument48 pagesBusinessman Hand Golden Key PowerPoint Templatesdeni wahyudinNo ratings yet

- Genres of Chinese Poetry: Shih, Sao, Fu, Lushi & MoreDocument10 pagesGenres of Chinese Poetry: Shih, Sao, Fu, Lushi & Morecristine joyNo ratings yet

- Highly Immersive ProgramDocument17 pagesHighly Immersive Programzaidi07No ratings yet

- VTU Project Report GuidelinesDocument2 pagesVTU Project Report GuidelinesAkhilesh Ravichandran83% (6)

- Springer Paper TemplateDocument9 pagesSpringer Paper TemplateAyush JNo ratings yet

- 42947-IJPRT-Instruction For AuthorsDocument7 pages42947-IJPRT-Instruction For AuthorsAndrés Berrío AlzateNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Beauty SalonDocument7 pagesLiterature Review of Beauty Salonfvf66j19100% (1)

- 張詩勤全文Document181 pages張詩勤全文13006655363No ratings yet

- Parenthetical Documentation Cheat Sheet (A.k.a. In-Text Citations)Document5 pagesParenthetical Documentation Cheat Sheet (A.k.a. In-Text Citations)Ova Ra AkbarNo ratings yet

- Calligraphy Introduction 2Document3 pagesCalligraphy Introduction 2MJ BotorNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Machine ShorthandDocument11 pagesModule 6 Machine ShorthandJulius A. MuicoNo ratings yet

- MultiSyllable IeDocument4 pagesMultiSyllable Iee.v.nicholsNo ratings yet

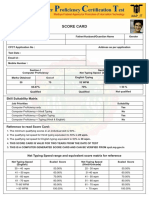

- CPCT - Score Card - CDRDocument1 pageCPCT - Score Card - CDRmuskan onlineNo ratings yet

- Regents Writing GuideDocument10 pagesRegents Writing GuideprettylocxterNo ratings yet

- Political Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandPolitical Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Christian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesFrom EverandChristian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Jack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesFrom EverandJack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Patricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideFrom EverandPatricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Help! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyFrom EverandHelp! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyNo ratings yet

- Colleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListFrom EverandColleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListNo ratings yet

- 71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Sources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksFrom EverandSources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksNo ratings yet

- David Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderFrom EverandDavid Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderNo ratings yet

- 71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- My Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsFrom EverandMy Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsNo ratings yet

- American Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersFrom EverandAmerican Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreFrom EverandEnglish Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Seven Steps to Great LeadershipFrom EverandSeven Steps to Great LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Myanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionFrom EverandMyanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionNo ratings yet

- Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to EcofictionFrom EverandWhere the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to EcofictionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Seeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksFrom EverandSeeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksNo ratings yet

- Memory of the World: The treasures that record our history from 1700 BC to the present dayFrom EverandMemory of the World: The treasures that record our history from 1700 BC to the present dayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

![[Ancient Language Resources] H. St J. Thackeray, K. C. Hanson - A Grammar of the Old Testament in Greek_ According to the Septuagint_ Introduction, Orthography, and Accidence Volume 1(1909, Wipf & Stock Publishers.pdf](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/405416225/149x198/812e7612cd/1554734222?v=1)