Professional Documents

Culture Documents

LO Week 5

Uploaded by

noorgianilestariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

LO Week 5

Uploaded by

noorgianilestariCopyright:

Available Formats

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ICM 1 WEEK V

LO.1. > Rotator Cuff tear , when one or more of the rotator cuff tendons is torn, the

tendon no longer fully attaches to the head of the humerus. Most tears occur in the

supraspinatus muscle and tendon, but other parts of the rotator cuff may also be

involved.

In many cases, torn tendons begin by fraying. As the damage progresses, the tendon

can completely tear, sometimes with lifting a heavy object.

There are different types of tears :

1. Partial Tear, this type of tear damages the soft tissue, but does not completely

sever it.

2. Full-Thickness Tear, this type of tear is also called a complete tear. It splits the

soft tissue into two pieces. In many cases, tendons tear off where they attach

to the head of the humerus. With a full-thickness tear, there is basically a hole

in the tendon.

there are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: injury and degeneration.

Acute tear, if fall down on outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking

motion, can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur with other shoulder

injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

Degenerative tear, most tears are the result of a wearing down of the tendon that

occurs slowly over time or by rotator cuff impingement. This degeneration naturally

occurs as we age. Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm. If you

have a degenerative tear in one shoulder, there is a greater risk for a rotator cuff tear

in the opposite shoulder -- even if you have no pain in that shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears :

- Repetitive stress. Repeating the same shoulder motions again and again can

stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and

weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for

overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply. As we get older, the blood supply in our rotator cuff

tendons lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body's natural ability to

repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs. As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the

underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the

rotator cuff tendon. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over

time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

Pain at rest and at night, particularly if lying on the affected shoulder

Pain when lifting and lowering your arm or with specific movements

Weakness when lifting or rotating your arm

Crepitus or crackling sensation when moving your shoulder in certain positions

Tears that happen suddenly, such as from a fall, usually cause intense pain. There may be a

Noorgiani Lestari-07120100056

snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm

LO.2. > Rotator cuff tendinitis refers to irritation of these tendons and inflammation

of the bursa (a normally smooth layer) lining these tendons or damage the rotator cuff

tendons. A rotator cuff tear occurs when one of the tendons is torn from overuse or

injury.

Symptoms :

Early on, pain occurs with overhead activities and lifting your arm to the side.

Activities include brushing hair, reaching for objects on shelves, or playing an

overhead sport.

Pain is more likely in the front of the shoulder and may radiate to the side of the

arm. However, this pain always stops before the elbow. If the pain travels

beyond the arm to the elbow and hand, this may indicate a pinched nerve.

There may also be pain with lowering the shoulder from a raised position.

At first, this pain may be mild and occur only with certain movements of the

arm. Over time, pain may be present at rest or at night, especially when lying on the

affected shoulder. Weakness and loss of motion when raising the arm above your

head. Your shoulder can feel stiff with lifting or movement. It may become more

difficult to place the arm behind your back.

LO.3.>Frozen shoulder, also called adhesive capsulitis, causes pain and stiffness in

the shoulder. Over time, the shoulder becomes very hard to move.

Frozen shoulder occurs in about 2% of the general population. It most commonly

affects people between the ages of 40 and 60, and occurs in women more often than

men.

frozen shoulder, the shoulder capsule thickens and becomes tight. Stiff bands of

tissue called adhesions develop. In many cases, there is less synovial fluid in

the joint.

The hallmark sign of this condition is being unable to move your shoulder - either on

your own or with the help of someone else. It develops in three stages:

1. Freezing, In the"freezing" stage, you

slowly have more and more pain. As

the pain worsens, your shoulder loses

range of motion. Freezing typically

lasts from 6 weeks to 9 months.

2. Frozen, Painful symptoms may

actually improve during this stage, but

the stiffness remains. During the 4 to 6

months of the "frozen" stage, daily

activities may be very difficult.

3. Thawing, Shoulder motion slowly

improves during the "thawing" stage.

Complete return to normal or close to

normal strength and motion typically

takes from 6 months to 2 years.

The causes of frozen shoulder are not fully understood. There is no clear connection

to arm dominance or occupation. A few factors may put you more at risk for

developing frozen shoulder.

Diabetes. Frozen shoulder occurs much more often in people with diabetes, affecting

10% to 20% of these individuals. The reason for this is not known.

Other diseases. Some additional medical problems associated with frozen shoulder

include hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Parkinson's disease, and cardiac disease.

Immobilization. Frozen shoulder can develop after a shoulder has been immobilized

for a period of time due to surgery, a fracture, or other injury. Having patients move

their shoulders soon after injury or surgery is one measure prescribed to prevent

frozen shoulder.

Pain from frozen shoulder is usually dull or aching. It is typically worse early in the

course of the disease and when you move your arm. The pain is usually located over

the outer shoulder area and sometimes the upper arm.

LO.4.> Paraneoplastic syndromes are a group of rare disorders that are triggered by

an abnormal immune system response to a cancerous tumor known as a "neoplasm."

Paraneoplastic syndromes are thought to happen when cancer-fighting antibodies or

white blood cells (known as T cells) mistakenly attack normal cells in the nervous

system. These disorders typically affect middle-aged to older people and are most

common in individuals with lung, ovarian, lymphatic, or breast cancer. Neurologic

symptoms generally develop over a period of days to weeks and usually occur prior to

the tumor being discovered. These symptoms may include difficulty in walking or

swallowing, loss of muscle tone, loss of fine motor coordination, slurred speech,

memory loss, vision problems, sleep disturbances, dementia, seizures, sensory loss in

the limbs, and vertigo or dizziness. Paraneoplastic syndromes include Lambert-Eaton

myasthenic syndrome, stiff-person syndrome, encephalomyelitis, myasthenia gravis,

cerebellar degeneration, limbic or brainstem encephalitis, neuromyotonia, opsoclonus,

and sensory neuropathy.

The pathophysiology of paraneoplastic syndromes is complex and intriguing.

When a tumor arises, the body may produce antibodies to fight it by binding to and

destroying tumor cells. Unfortunately, in some cases, these antibodies cross-react with

normal tissues and destroy them, which may result in a paraneoplastic disorder.[5]

For example, antibodies or T cells directed against the tumor may mistakenly attack

normal nerve cells. The detection of paraneoplastic anti-neural antibody was first

reported in 1965.[6]

In other cases, paraneoplastic syndromes result from the production and release of

physiologically active substances by the tumor. Tumors may produce hormones,

hormone precursors, a variety of enzymes, or cytokines. Several cancers produce

proteins that are physiologically expressed in utero by embryonic and fetal cells but

not expressed by normal adult cells. These substances may serve as tumor markers

(eg, carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], alpha-fetoprotein [AFP], carbohydrate antigen

19-9 [CA 19-9]). More rarely, the tumor may interfere with normal metabolic

pathways or steroid metabolism. Finally, some paraneoplastic syndromes are

idiopathic.

Paraneoplastic syndromes most commonly occur in patients not known to have

cancer, as well as in those with active cancer and those in remission after treatment. A

complete history and physical examination findings can suggest neoplasia. Persons

with a family history of malignancies (eg, breast,[7, 8] colon) may be at increased risk

and should be screened for cancer. Nonspecific syndromes can precede the clinical

manifestations of the tumor, and this occurrence is a negative prognostic factor.

Because of their complexity and variety, the clinical presentations of these syndromes

may vary greatly. Usually, paraneoplastic syndromes are divided into the following

categories: (1) miscellaneous (nonspecific), (2) rheumatologic, (3) renal, (4)

gastrointestinal, (5) hematologic, (6) cutaneous, (7) endocrine, and (8) neuromuscular.

Miscellaneous (nonspecific)

Fever, dysgeusia, anorexia, and cachexia

are included in this category.

Fever is frequently associated with

lymphomas,[9] acute leukemias,

sarcomas, renal cell carcinomas

(Grawitz tumors), and digestive

malignancies (including the liver).

Rheumatologic

Paraneoplastic arthropathies arise as

rheumatic polyarthritis[10] or

polymyalgia, particularly in patients

with myelomas; lymphomas; acute

leukemia; malignant histiocytosis;

and tumors of the colon, pancreas,

prostate, and CNS.

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy may be

observed in patients with lung

cancers, pleural mesothelioma, or

phrenic neurilemmoma.

Scleroderma may precede direct evidence

of tumor

The widespread form is typical of

malignancies of the breast,

uterus, and lung (both alveolar

and bronchial forms).

The localized form is characteristic

of carcinoids and of lung

tumors (bronchoalveolar

forms).

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may

develop in patients with lymphomas

or cancers of the lung, breast, or

gonads.

Secondary amyloidosis of the connective

tissues is a rare presentation in

patients with myeloma, renal

carcinoma, and lymphomas.

Renal

Hypokalemic nephropathy, which is

characterized by urinary potassium

leakage of more than 20 mEq per 24

hours, may develop in patients with

tumors that secrete

adrenocorticotropic hormone

(ACTH) or ACTH-like substances. It

occurs in 50% of individuals with

ACTH-secreting tumors of the lung

(ie, small cell lung cancer[11] ).

Hypokalemia, hyponatremia or

hypernatremia, hyperphosphatemia,

and alkalosis or acidosis may result

from other types of tumors that

produce ACTH, antidiuretic hormone

(ADH), or gut hormones (see

Endocrine and neuromuscular,

below).

Nephrotic syndrome is observed, although

infrequently, in patients who have

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL); non-

Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL);

leukemias; melanomas; or

malignancies of lung, thyroid, colon,

breast, ovary, or pancreatic head.

Secondary amyloidosis of the kidneys,

heart, or CNS may rarely be a

presenting feature in patients with

myeloma, renal carcinoma, or

lymphomas. The clinical picture of

secondary amyloidosis is related to

renal and cardiac injuries.

Gastrointestinal

Watery diarrhea[12] accompanied by an

electrolyte imbalance leads to

asthenia, confusion, and exhaustion.

These problems are typical of patients with

proctosigmoid tumors (both benign

and malignant) and of medullary

thyroid carcinomas (MTCs) that

produce several prostaglandins (PGs;

especially PG E2 and F2) that lead to

malabsorption and, consequently,

unavailability of nutrients.

These alterations also can be observed in

patients with melanomas, myelomas,

ovarian tumors, pineal body tumors,

and lung metastases.

Hematologic

Symptoms related to erythrocytosis or

anemia,[12] thrombocytosis,

disseminated intravascular

coagulation (DIC), and leukemoid

reactions may result from many types

of cancers.

In some cases, symptoms result from

migrating vascular thrombosis (ie,

Trousseau syndrome)[13] occurring

in at least 2 sites.

Leukemoid reactions, characterized by the

presence of immature WBCs in the

bloodstream, are usually

accompanied by hypereosinophilia

and itching. These reactions are

typically observed in patients with

lymphomas or cancers of the lung,

breast, or stomach.

Cryoglobulinemia may occur in patients

with lung cancer or pleural

mesothelioma.

Cutaneous[14]

Itching is the most frequent cutaneous

manifestation in patients with cancer.

Herpes zoster, ichthyosis,[15] flushes,

alopecia, or hypertrichosis also may

be observed.

Acanthosis nigricans and dermic melanosis

are characterized by a blackish

pigmentation of the skin and usually

occur in patients with metastatic

melanomas or pancreatic tumors.

Endocrine

Endocrine symptoms related to

paraneoplastic syndromes usually

resemble the more common

endocrine disorders (eg, Cushing

syndrome). Neuromuscular

symptoms may mimic common

neurological conditions (eg,

dementia).

Cushing syndrome, accompanied by

hypokalemia, very high plasma

ACTH levels, and increased serum

and urine cortisol concentrations, is

the most common example of an

endocrine disorder linked to a

malignancy.[16, 17, 3, 18] This is

related to the ectopic production of

ACTH or ACTH-like molecules from

many tumors (eg, small cell cancer of

the lung).

Neuromuscular

Neuromuscular disorders related to cancers

are now included among the

paraneoplastic syndromes. Such

disorders affect 6% of all patients

with cancer and are prevalent in

ovarian and pulmonary cancers.

Examples include the following:

Myasthenia gravis[19] is the most

common paraneoplastic

syndrome in patients with

thymoma,[20] a malignancy

arising from epithelial cells of

the thymus. Indeed, thymoma

is the underlying cause in

approximately 10% to 15% of

cases of myasthenia

gravis.[21] Rarely,

hypogammaglobulinemia and

pure red cell aplasia occur as

paraneoplastic syndromes in

patients with thymoma.[20]

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic

syndrome (LEMS), which

manifests as asthenia of the

scapular and pelvic girdles

and a reduction of tendon

reflexes. LEMS sometimes

can be accompanied by

xerostomia, sexual impotence,

myopathy, and peripheral

neuropathy. It is associated

with cancer 40-70% of the

time, most commonly small

cell lung cancer (SCLC). It

seems to result from

interference with the release

of acetylcholine due to

immunologic attack against

the presynaptic voltage-gated

calcium channel.

Opsoclonus-myoclonus

syndrome[22] usually affects

children younger than 4 years.

It is associated with

hypotonia, ataxia, and

irritability. One in two

patients has neuroblastoma.

Paraneoplastic limbic

encephalitis[23] is

characterized by depression,

seizures, irritability, and

short-term memory loss. The

neurologic symptoms develop

rapidly and can resesmble

dementia. Paraneoplastic

limbic encephalitis is most

commonly associated with

SCLC.[24]

Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis is

characterized by a complex of

symptoms derived from

brainstem encephalitis, limbic

encephalitis, cerebellar

degeneration, myelitis, and

autonomic dysfunction. Such

neurologic deficits and signs

seem to be related to an

inflammatory process

involving multiple areas of

the nervous system.

Paraneoplastic cerebellar

degeneration causes gait

difficulties, dizziness, nausea,

and diplopia, followed by

ataxia, dysarthria, and

dysphagia. Paraneoplastic

cerebellar degeneration is

frequently associated with

Hodgkin lymphoma,[25]

breast cancer,[26] SCLC, and

ovarian cancer; it may occur

in association with prostate

carcinoma.[27]

Paraneoplastic sensory neuropathy

affects lower and upper

extremities and is

characterized by progressive

sensory loss, either symmetric

or asymmetric. It seems to be

related to the loss of the

dorsal root ganglia with early

involvement of major fibers

responsible for detecting

vibration and position.

You might also like

- Lebel Contoh PrintDocument1 pageLebel Contoh PrintnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Kahlil Gibran Part ViiDocument1 pageKahlil Gibran Part ViinoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Supraventricular TachycardiaDocument37 pagesSupraventricular TachycardianoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Proteomic ReportDocument25 pagesProteomic ReportnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- ACHMDocument1 pageACHMnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Body Dysmorphic TraynorDocument12 pagesBody Dysmorphic TraynornoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Fluid and Electrolyte TherapyDocument136 pagesBasic Concepts of Fluid and Electrolyte Therapynoorgianilestari100% (2)

- Medical Disciplinary-Tugas Prof EkaDocument3 pagesMedical Disciplinary-Tugas Prof EkanoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Pa To GenesisDocument1 pagePa To GenesisnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Hipertensi, Diabetes dan AsmaDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Hipertensi, Diabetes dan AsmanoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Van Den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Et Al. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med 345: 1359-1367, 2001Document1 pageVan Den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Et Al. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med 345: 1359-1367, 2001noorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Van Den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Et Al. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med 345: 1359-1367, 2001Document1 pageVan Den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Et Al. Intensive Insulin Therapy in Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med 345: 1359-1367, 2001noorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Family Medicine Residents Orthopedic Rotation HandoutDocument18 pagesFamily Medicine Residents Orthopedic Rotation HandoutRuth PoeryNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument30 pagesBlood TransfusionnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Koas IPDDocument11 pagesJadwal Koas IPDnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis MeningitisDocument25 pagesDiagnosis MeningitisnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Hasil UrinalysisDocument1 pageHasil UrinalysisnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Visum et repertum report 1 October 2014Document4 pagesVisum et repertum report 1 October 2014noorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Otitis Media AkutDocument9 pagesOtitis Media AkutnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Frozen ShoulderDocument14 pagesFrozen ShouldernoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- WEEK Orthopedics DR JohnDocument16 pagesWEEK Orthopedics DR JohnnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

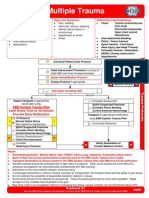

- Multiple Trauma: EMS System Trauma Plan Limit Scene Time To 10 Minutes Provide Early NotificationDocument1 pageMultiple Trauma: EMS System Trauma Plan Limit Scene Time To 10 Minutes Provide Early NotificationKelly JacksonNo ratings yet

- CiminoDocument2 pagesCiminonoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis MeningitisDocument25 pagesDiagnosis MeningitisnoorgianilestariNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Flight Instructor Patter Ex17Document1 pageFlight Instructor Patter Ex17s ramanNo ratings yet

- Pub - Perspectives On Global Cultures Issues in Cultural PDFDocument190 pagesPub - Perspectives On Global Cultures Issues in Cultural PDFCherlyn Jane Ventura TuliaoNo ratings yet

- Agitators: Robert L. Bates, President Chemineer, IncDocument24 pagesAgitators: Robert L. Bates, President Chemineer, InctenshinomiyukiNo ratings yet

- Footprints 080311 For All Basic IcsDocument18 pagesFootprints 080311 For All Basic IcsAmit PujarNo ratings yet

- WP1019 CharterDocument5 pagesWP1019 CharternocnexNo ratings yet

- Soil Testing Lab Results SummaryDocument2 pagesSoil Testing Lab Results SummaryMd SohagNo ratings yet

- 2022 - J - Chir - Nastase Managementul Neoplaziilor Pancreatice PapilareDocument8 pages2022 - J - Chir - Nastase Managementul Neoplaziilor Pancreatice PapilarecorinaNo ratings yet

- Graphs & Charts SummariesDocument20 pagesGraphs & Charts SummariesMaj Ma Salvador-Bandiola100% (1)

- Community Development A Critical Approach PDFDocument2 pagesCommunity Development A Critical Approach PDFNatasha50% (2)

- All Types of Switch CommandsDocument11 pagesAll Types of Switch CommandsKunal SahooNo ratings yet

- Vsip - Info - Ga16de Ecu Pinout PDF FreeDocument4 pagesVsip - Info - Ga16de Ecu Pinout PDF FreeCameron VeldmanNo ratings yet

- RFID Receiver Antenna Project For 13.56 MHZ BandDocument5 pagesRFID Receiver Antenna Project For 13.56 MHZ BandJay KhandharNo ratings yet

- Jiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. SOT-89-3L Transistor SpecificationsDocument2 pagesJiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. SOT-89-3L Transistor SpecificationsIsrael AldabaNo ratings yet

- Monetary System 1Document6 pagesMonetary System 1priyankabgNo ratings yet

- MATH6113 - PPT5 - W5 - R0 - Applications of IntegralsDocument58 pagesMATH6113 - PPT5 - W5 - R0 - Applications of IntegralsYudho KusumoNo ratings yet

- The Power of Networking for Entrepreneurs and Founding TeamsDocument28 pagesThe Power of Networking for Entrepreneurs and Founding TeamsAngela FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Fire Pump System Test ReportDocument12 pagesFire Pump System Test Reportcoolsummer1112143100% (2)

- GEd 105 Midterm ReviewerDocument17 pagesGEd 105 Midterm ReviewerAndryl MedallionNo ratings yet

- Classification of MatterDocument2 pagesClassification of Matterapi-280247238No ratings yet

- English ProjectDocument10 pagesEnglish ProjectHarshman Singh HarshmanNo ratings yet

- Pankaj Screener 10 Oct 2014Document127 pagesPankaj Screener 10 Oct 2014Sadul Singh Naruka100% (1)

- Ethics Book of TAMIL NADU HSC 11th Standard Tamil MediumDocument140 pagesEthics Book of TAMIL NADU HSC 11th Standard Tamil MediumkumardjayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - The Empirical Beginnings and Basic Contents of Educational PsychologyDocument9 pagesChapter 1 - The Empirical Beginnings and Basic Contents of Educational PsychologyJoshua Almuete71% (7)

- Unit 01 Family Life Lesson 1 Getting Started - 2Document39 pagesUnit 01 Family Life Lesson 1 Getting Started - 2Minh Đức NghiêmNo ratings yet

- Hearing God Through Biblical Meditation - 1 PDFDocument20 pagesHearing God Through Biblical Meditation - 1 PDFAlexander PeñaNo ratings yet

- LAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023Document16 pagesLAU Paleoart Workbook - 2023samuelaguilar990No ratings yet

- Escalado / PLC - 1 (CPU 1214C AC/DC/Rly) / Program BlocksDocument2 pagesEscalado / PLC - 1 (CPU 1214C AC/DC/Rly) / Program BlocksSegundo Angel Vasquez HuamanNo ratings yet

- "The Meeting of Meditative Disciplines and Western Psychology" Roger Walsh Shauna L. ShapiroDocument13 pages"The Meeting of Meditative Disciplines and Western Psychology" Roger Walsh Shauna L. ShapiroSayako87No ratings yet

- Clinnic Panel Penag 2014Document8 pagesClinnic Panel Penag 2014Cikgu Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- AWS S3 Interview QuestionsDocument4 pagesAWS S3 Interview QuestionsHarsha KasireddyNo ratings yet