Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In Conversation With Anne Sebba

Uploaded by

Heidi KingstoneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In Conversation With Anne Sebba

Uploaded by

Heidi KingstoneCopyright:

Available Formats

__________________________________________________________________________________

1

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

March 16

th

2011

Heidi Kingstone in conversation with Anne Sebba.

I wanted to start off and talk about my life in Kabul, which is fairly normal in an

abnormal place. Life there is referred to as The Kabubble, and I think most of us are

aware of the parallel existences we live compared to the lives most Afghans live.

My day starts off quite normally. The house I live in is a bungalow and is divided into

two halves. Each morning I pad over to the neighbours and use her coffee machine to

make coffee. Around that time I promise myself that i will do the Cindy Crawford work

out DVD but generally I put it off.

The house is one of those beautiful old Afghan style homes not dissimilar from

something Frank Lloyd Wright might have designed. During Taliban times it probably

would have cost about $200.00 a month to rent, if that. These days the war economy has

inflated the price of everything.

Everything, too, in Afghanistan is behind high walls and closed gates. Once you walk

though the unassuming doors you enter into a large garden, which attracts a legion of

feral cats and is home to a solitary rabbit.

I have a bathroom, a bedroom, a kitchen - that I hardly use a living room and a

conservatory that we call the winter garden the idea was to remind us of the ice house

in the film Dr Zhivago.

Despite the high walls everyone on the street know exactly what is going on. Men are

called chawkidors - security guards - keep watch. They are unarmed, and your safety is

really in their hands. We live in a low key way - no guns - and these men know

everything that goes on in the 'hood.

Outside the front door are the muddy streets which I often walk down to go to Flower

Street Cafe, an internet cafe, which is very confusingly not anywhere near Flower Street,

which is near Chicken Street in the Shar-e-Naw district.

Most of us use it as an office, despite its creakingly slow internet and undrinkable coffee.

We use it by force of habit but also because putting in high speed internet can cost about

__________________________________________________________________________________

2

$3000.00 - and more. It is also a meeting place, which is part of its charm. Kabul is a like

a small village of foreigners, including Afghan ex-pats, catapulted in the larger town of

Kabul - it is the type of place where everyone knows everyone.

I usually leave FSC about 4 or 5pm in winter - but before it gets dark, for reasons of

security. You can't talk about Afghanistan, or Kabul, without mentioning security.

Security is a the back of everyone's mind, but it is Afghans who are murdered and

particularly Afghan businessmen who are kidnapping targets.

As a result most foreigners don't walk. To travel around the city four taxi companies

cater to ex-pats - the newest one is called Hope. Needless to say there are all sorts of

jokes like - hope you get there. Inshallah.

No matter what you do from getting out of the car to waking across the street you

inevitably get caked in mud. Kabul is a city of mud and dust. It's dirty outside defintely

but you also breath in an enormous amount of fecal matter that floats in the air- the air

itself is very polluted and it is estimated that everyday spent in Kabul is akin to smoking

two packs of cigarettes a day. I don't want you to think that most of just get splattered

in mud because there is also a vigorous social scene. Most people work extremely hard,

and the intensity of the environment is a contributing factor.

I rarely spend a night in - one week I went to quiz night at the Golden Key Chinese

Restaurant. The food wasn't bad, but most of us couldnt name the seven dwarves but

did ok with the Greek mythology. Later with Richard Dunwoody, the jockey, we ended

up at the wrap party for a film that had just finished production. The next night the

social scene was totally different, a group of Afghan returnees, educated, successful,

interesting and engaged, entertained at a restaurant called Rumi, decorated in a 60s

style, and had been the elegant home of the owner's family. The conversation took place

in English, Dari and French.

Usually on Thursday nights, the start of the Afghan weekend, it's party night, admittedly

aimed at the 20 -30 year olds who have come to work in Kabul. One recent venue was

was a tent set up in a compound with carpets laid on the ground. plants dotted around,

loud western music, flashing lights, lots of dancing and alcohol. On aggregate men

outnumber women, the best phrase that sums up the situation is - the odds are good

but the goods are odd.

In the way that Helmand is not Afghanstan, for those of us who live in Britain and only

heard news about that particular southern province, Kabul in not Afghanistan. Kabul is

a protected city - protected by a ring of steel that clamps around it. It is a city of

sandbags, blast walls, hescos and barbed wire. The best analogy is to compare it to

living in a Graham Greene novel.

It is also a difficult place from which to tell reality from illusion. Kabul itself is booming.

Shopping malls sprout like mushrooms, roads are slowly being paved, the hills around

the city shine at night fuelled by city power, which did not exist a few years ago. A whole

construction industry has built up around the narcotecture that has also fuelled the

uncontrollable demand for poppy palaces, gaudy, garish, enormous, mirrored and vast

__________________________________________________________________________________

3

hideous houses.

It is a false economy equally fuelled by drug money and foreign aid money. Afghanistan

exports $400 million but imports $4 billion; very little internal market exists. While the

economy may be an illusion what is most definitely not illusion is the overall grim

reality of the situation for women.

While Afghanistan has over decades signed up to virtually every human rights treaty,

ratified a slew of laws protecting women and children and enshrined women's rights in

the constitution, no political will exists to implement them. The culture is becoming

increasingly conservative, and women's status remains frightening low. That is not the

whole picture but it is the overwhelming overview.

There have been some positive changes. Some women work, some are educated, some

are the main breadwinners supporting their families. In many women don't wear

burqas, and in the capital a few young girls bravely wear tight jeans, short jackets and

knee length boots. A new generation of impressive young men and women exists who

could be future leaders, given the opportunity. Any success women have had has to be

seen in pockets.

Compared to the ghost town that Kabul was after during and after the Taliban, Kabul

has transformed. The city had largely been destroyed by the mujahidin who preceded

the Taliban, and widows in burqas begged in the street for money to feed their children.

Widows are still the most disadvantaged sector of society.

Historically change has been imposed from the top down, by the elite who are

disconnected from the majority of Afghans who are some of the poorest people in the

world.

Illiteracy for women is still about 80 percent; domestic abuse is endemic. food

insecurity for men and women forms the basis of most Afghans main concern. I recently

asked an Afghan taxi driver what he thought of the political situation. He replied that he

didn't have time to think about that, his concern was how to feed his family.

Despite all these things, women, like women everywhere, are nuanced, amazing, some

are strong and powerful, smart and determined.

I wanted to tell you a few stories about some of the women I have met.

Last autumn I went to the north of Afghanistan to do some work for the German

government. Gul Jan was involved in one of the projects. She used a solar dryer for her

fruit and vegetables. She had one tooth left in her mouth, a long grey plait under her

white hijab, and a face wrinkled like a shar pei. She beamed and spoke about how happy

she was to have been involved in the project. Thrilled to get out of the house, to have

learned a skilled, to have felt important and useful and to contribute to her family's

income.

Hasina (not her real name) was in charge of one of the German projects. Like many

__________________________________________________________________________________

4

ShiaAfghans she had gone to Iran as a refugee but had returned to help other women.

Smart, insightful, modern over the last five years her original optimism had turned to

despair. In Kunduz, where Hasina lives, the Taliban have made in roads, and so threaten

daily life. She now wears a burka which she had not done before.

Hasina oversaw the disabled women's leather project. The women had eah lost a leg,

some in mine accidents. They were all very, very poor and were glad to have learned a

skill to be able to generate an income. but the reason they loved the project was that it

had brought them all together. They felt comfortable within this group and not like the

freaks they felt like outside, Hasina also told me how depressed women were and how

difficult their lives were. As if this needs any emphasis on one day I spoke to two

friends. One had to cancel meeting for dinner because she had to counsel a friend whose

sister had been killed by her in-laws. After that phone call another friend, who I was

sitting with, read out a text message she had just received, informing her that a high

school friend she had not seen for many years had been killed by her mother-in-law.

There are happy and sad tales, and Afghanistan remains an exotic, beautiful country, but

also one that if you don't go to Afghanistan as a feminist, you certainly return as one. As

one women I interviewed at a shelter said, in Afghanistan, all women have bad fate.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Upper Wimpole Street Literary Salon provides a forum for women writers to meet and exchange

ideas about ongoing work. We are a diverse group of over 100 writers from the fields of biography,

journalism, fiction, poetry and scriptwriting. We meet about 5 times a year in central London. Each salon

features members presenting a recently published book or a work-in-progress. Our informal setting

allows for frank discussion of our craft and of the particular challenges women writers face in promoting

and publishing their work.

You might also like

- Toppled in Baghdad, Clueless in WhitehallDocument6 pagesToppled in Baghdad, Clueless in WhitehallHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Suffering in Silence - The Jerusalem PostDocument4 pagesSuffering in Silence - The Jerusalem PostHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Can Both Peace and Justice Grow Out of The Turmoil in Volatile Sudan?Document1 pageCan Both Peace and Justice Grow Out of The Turmoil in Volatile Sudan?Heidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Iraqi Women See Upheaval As A Chance To Advance Their RightsDocument1 pageIraqi Women See Upheaval As A Chance To Advance Their RightsHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- A Little Goes A Long Way in War Torn AfghanistanDocument1 pageA Little Goes A Long Way in War Torn AfghanistanHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Iraq's 'Northern Alliance'Document2 pagesIraq's 'Northern Alliance'Heidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- While West Obsesses, The Front Line Talks of WarDocument1 pageWhile West Obsesses, The Front Line Talks of WarHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Returning Exiles Struggle To Make Sense of A Land With No DreamsDocument1 pageReturning Exiles Struggle To Make Sense of A Land With No DreamsHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Worst Refugee Crisis in The WorldDocument1 pageThe Worst Refugee Crisis in The WorldHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Iraqi TranslatorDocument4 pagesThe Iraqi TranslatorHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Human Rights Activitst Who Would Be President of LebanonDocument1 pageThe Human Rights Activitst Who Would Be President of LebanonHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- DiaryDocument1 pageDiaryHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- High Times in The Foothills of The HimalayasDocument1 pageHigh Times in The Foothills of The HimalayasHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- 'You Don't Know The Fear I Lived In'Document1 page'You Don't Know The Fear I Lived In'Heidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- A Nuclear SaladinDocument2 pagesA Nuclear SaladinHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Iranian JourneyDocument1 pageIranian JourneyHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- A Little Goes A Long Way in War Torn AfghanistanDocument1 pageA Little Goes A Long Way in War Torn AfghanistanHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Zagreb Is On A High... It Must Be All The CoffeeDocument1 pageZagreb Is On A High... It Must Be All The CoffeeHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Man With Afghanistan's Fate in His HandsDocument2 pagesThe Man With Afghanistan's Fate in His HandsHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- I Love ChiracDocument1 pageI Love ChiracHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Drive Through The 'Land of Eternal Winter'Document3 pagesDrive Through The 'Land of Eternal Winter'Heidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Reporting War & The Effect of New MediaDocument4 pagesReporting War & The Effect of New MediaHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Albania, The Hidden TreasureDocument1 pageAlbania, The Hidden TreasureHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Roddick ParadoxDocument1 pageRoddick ParadoxHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- What If The Kabubble Bursts?Document6 pagesWhat If The Kabubble Bursts?Heidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Arafat Is Riding A TigerDocument1 pageArafat Is Riding A TigerHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Storming of NormanDocument1 pageThe Storming of NormanHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- You Could Cut The Atmosphere With A KnifeDocument1 pageYou Could Cut The Atmosphere With A KnifeHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Death in Fiji Looked On Cards For McKinnonDocument1 pageDeath in Fiji Looked On Cards For McKinnonHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The ExileDocument2 pagesThe ExileHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- AdamhenryDocument11 pagesAdamhenryapi-349031810No ratings yet

- Login: AO VIVODocument5 pagesLogin: AO VIVOFagner CruzNo ratings yet

- Department of Agriculture Farm-To-Market Roads: Official Gazette 'Document29 pagesDepartment of Agriculture Farm-To-Market Roads: Official Gazette 'russell obligacionNo ratings yet

- Company Law: Study TextDocument11 pagesCompany Law: Study TextTimo PaulNo ratings yet

- The Titanic: How Was Titanic Made?Document4 pagesThe Titanic: How Was Titanic Made?AprilNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Grave and Sudden Provocation:An Analysis As Defence With Respect To Provisions of Indian Penal CodeDocument31 pagesAssignment: Grave and Sudden Provocation:An Analysis As Defence With Respect To Provisions of Indian Penal Codevinay sharmaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Corruption Speech TextDocument1 pageAnti-Corruption Speech TextBeryl CholifNo ratings yet

- G C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerDocument4 pagesG C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerChristine Torrepenida RasimoNo ratings yet

- AhalyaDocument10 pagesAhalyanieotyagiNo ratings yet

- Mini Mock Bar Rem - NeriDocument4 pagesMini Mock Bar Rem - NeriTauniño Jillandro Gamallo NeriNo ratings yet

- Q Paper English Language 2013Document14 pagesQ Paper English Language 2013Trade100% (1)

- Anatomy and Physiology of Male Reproductive SystemDocument8 pagesAnatomy and Physiology of Male Reproductive SystemAdor AbuanNo ratings yet

- Juridical Capacity and Capacity To ActDocument4 pagesJuridical Capacity and Capacity To ActChap ChoyNo ratings yet

- 7 CALUZOR v. Llanillo, July 1, 2015, G.R. No. 155580Document4 pages7 CALUZOR v. Llanillo, July 1, 2015, G.R. No. 155580SORITA LAWNo ratings yet

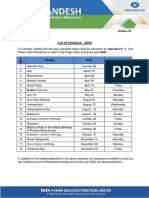

- Holiday List - 2020Document3 pagesHoliday List - 2020nitin369No ratings yet

- Addressing Social Issues in the PhilippinesDocument3 pagesAddressing Social Issues in the PhilippinesAaron Santiago OchonNo ratings yet

- Demat Account Closure Form PDFDocument1 pageDemat Account Closure Form PDFRahul JainNo ratings yet

- Purpose: To Ascertain and Give Effect To The Intent of The LawDocument11 pagesPurpose: To Ascertain and Give Effect To The Intent of The LawApril Rose Flores FloresNo ratings yet

- Villanueva vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageVillanueva vs. Court of AppealsPNP MayoyaoNo ratings yet

- Final Tilikum V SeaWorld ComplaintDocument20 pagesFinal Tilikum V SeaWorld ComplaintRene' HarrisNo ratings yet

- North 24 Parganas court document on property disputeDocument5 pagesNorth 24 Parganas court document on property disputeBiltu Dey89% (9)

- Alice AdventuresDocument3 pagesAlice Adventuresapi-464213250No ratings yet

- How To Get A Passport For A U.S. Citizen Child Under The Age 16Document7 pagesHow To Get A Passport For A U.S. Citizen Child Under The Age 16J CoxNo ratings yet

- Access To Public Records in NevadaDocument32 pagesAccess To Public Records in NevadaLas Vegas Review-JournalNo ratings yet

- Flight Detls: Guwahati To New Delhi 29 Jun 11: PriceDocument12 pagesFlight Detls: Guwahati To New Delhi 29 Jun 11: Pricevsda007No ratings yet

- Dreadful MutilationsDocument2 pagesDreadful Mutilationsstquinn864443No ratings yet

- Vs 3 GuideDocument3 pagesVs 3 Guideapi-260052009No ratings yet

- Caste in Contemporary India Divya VaidDocument23 pagesCaste in Contemporary India Divya Vaidshyjuhcu3982No ratings yet

- LwOffz S-Z 2018 PDFDocument934 pagesLwOffz S-Z 2018 PDFJean Paul Sikkar100% (1)

- Memories Currencies of CountriesDocument13 pagesMemories Currencies of CountriesQIE PSNo ratings yet