Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comdev - Jim Ife

Uploaded by

Azman Hafid57%(7)57% found this document useful (7 votes)

3K views386 pagesThe book explores the interrelated Irameworks oI social justice, ecological responsibility and post-enlightenment thinking. It promotes a holistic approach to Community Development and emphasises the diIerent dimensions oI human community. Written in Jim IIes characteristic engaging and accessible style, Communitv Development in an Uncertain World is an essential resource Ior students and practitioners now more than ever.

Original Description:

Original Title

Comdev- Jim Ife

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe book explores the interrelated Irameworks oI social justice, ecological responsibility and post-enlightenment thinking. It promotes a holistic approach to Community Development and emphasises the diIerent dimensions oI human community. Written in Jim IIes characteristic engaging and accessible style, Communitv Development in an Uncertain World is an essential resource Ior students and practitioners now more than ever.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

57%(7)57% found this document useful (7 votes)

3K views386 pagesComdev - Jim Ife

Uploaded by

Azman HafidThe book explores the interrelated Irameworks oI social justice, ecological responsibility and post-enlightenment thinking. It promotes a holistic approach to Community Development and emphasises the diIerent dimensions oI human community. Written in Jim IIes characteristic engaging and accessible style, Communitv Development in an Uncertain World is an essential resource Ior students and practitioners now more than ever.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 386

COMMUNITY

DEVELOPMENT

IN AN

UNCERTAIN WORLD

VISTON, ANALYSIS AND PRACTICE

JIM IFE

Community Development in an Uncertain

World

Vision, analysis and practice

Community Development in an Uncertain World provides a comprehensive and lively introduction

to modern community development. The book explores the interrelated frameworks of social justice,

ecological responsibility and post-Enlightenment thinking, drawing on various sources including the

wisdom of Indigenous peoples, Recognising the increasing complexity and uncertainty of the times in

which we live, Jim Ife promotes a holistic approach to community development and emphasises the

different dimensions of human community: social, economic, political, cultural, environmental,

spiritual, personal and survival

‘The first section of the book examines the major theories and concepts that underpin community

development. This includes a discussion of core principles: change and wisdom ‘from below’, the

importance of process and valuing diversity. The second section focuses on practical elements, such

as community work roles and essential skills. The final chapters discuss the problematic context of

much contemporary practice and offer vision and hope for the future.

Written in Jim Ife’s characteristic engaging and accessible style, Community Development in an

Uncertain World is an essential resource for students and practitioners — now more than ever.

Emeritus Professor Jim Ife holds adjunct positions at the Centre for Human Rights Education at

Curtin University, Perth, at the Centre for Citizenship and Human Rights at Deakin University, and at

Victoria University, Melbourne.

Community Development in an Uncertain

World

Vision, analysis and practice

Jim Ife

CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, So Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City

Cambridge University Press

477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107628496

© Cambridge University Press 2013

This publication is copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant

collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written

permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published by Pearson Education as Community Development in 1995

Second edition 2002

First published by Cambridge University Press as Community Development in an Uncertain World

in 2013

Cover design by Marianna Berek-Lewis

Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd

Printed in China by Print Plus Ltd

A catalogue record for this publication ts available from the British Library

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the catalogue of the National Library of

Australia at www nla,gov.au

ISBN 978-1-107-62849-6 Paperback

Reproduction and communication for educational purposes

‘The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of the pages

of this work, whichever is the greater, to be reproduced and/or communicated by any educational

institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or the body that

administers if) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

For details of the CAL licence for educational institutions contact:

Copyright Agency Limited

Level 15, 233 Castlereagh Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Telephone: (02) 9394 7600

Facsimile: (02) 9394 7601

E-mail: info@copyright.com.au

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for

external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any

content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Contents

List of figures and tables

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The crisis in human services and the need for community

‘The crisis in the welfare state and the emergence of neo-liberalism

Away forward

Commumity-based services as an alternative

‘The missing ingredient: community devel opment

‘The next steps

2 Foundations of commumity development: An ecological perspective

Crisis

Environmental responses and Green responses

‘Themes within Green analysis

An ecological perspective

An ecological perspective: is it enough?

3 Foundations of community development: A social justice perspective

Approaches to disadvantage: the limitations of social policy

Empowerment

Need

Rights

4 Foundations of community development: Beyond Enlightenment modernity

‘The Enlightenment

Beyond the Enlightenment

Indigenous understandings

Conclusion

5 A vision for community devel opment

Why each perspective is insufficient unless informed by the others

‘The promise of integration

Community

Development

Community-based human services

An alternative vision: grounds for hope

6 Change from below

Valuing local knowledge

Valuing local culture

Valuing local resources

Valuing local skills

Valuing local processes

Working in solidarity

Ideological and theoretical foundations for change from below

Conclusion

7 The process of commmity devel opment

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Process and outcome

‘The integrity of process

Consciousness-raising

Participatory democracy

Cooperation

‘The pace of development

Peace and non-violence

Consensus

Commumity-buil ding

Conclusion

‘The global and the local

Globalisation

Localisation

Protest

Global and local practice

Universal and contextual issues

Colonialism, colonialist practice and working internationally

Guarding against colonialist practice

Working internationally

Community devel opment: Social, economic and political

Social development

Economic development

Political devel opment

Community devel opment: Cultural, environmental, spiritual, personal and survival

Cultural devel opment

Environmental development

Spiritual development

Personal devel opment

Survival development

Balanced development

Principles of community development and their application to practice

Foundational principles

Principles of valuing the local

Process principles

Global and local principles

Conclusion

Roles and skills 1: Facilitative and educational

With head, heart, hand and feet

‘The problem with ‘cookbooks*

Competencies

Practice, theory, reflection and praxis

‘The language of roles

Facilitative roles and skills

Educational roles and skills

Roles and skills 2: Representational and technical

15

16

Refer

Index

Representational roles and skills

Technical roles and skills

‘Two special cases: needs assessment and evaluation

Demystifying skills

‘The organisational context

Managerialism

Responding to managerialism: community development as subversive

Introducing community devel opment processes: the power of the collective

Conclusion

Practice issues

Practice frameworks

Categories of community worker

Values and ethics

Professionalism

Education and training

‘The use and abuse of power

Internal and external community work

Long-term commitment

Support

Passion, vision and hope

ences

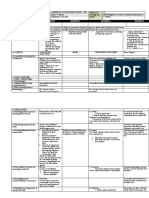

Figures and tables

Figure 5.1. The vision of community devel opment

Figure 10.1 Integrated community development

Figure 10.2 Social devel opment

Figure 10.3 Community economic development

Figure 10.4 Political development

Figure 11.1 Cultural development

Figure 13.1 Commumity work practice roles

Figure 16.1 A framework for community workers

Table 2.1 Schools of Green thought

Table 2.2 An ecological perspective

Table 3.1 Accounts of social issues

Table 3.2 Perspectives on power

Table 3.3. Empowerment

Table 3.4 Types of need statements

Table 16.1 Categories of community workers

Acknowledgements

‘The ideas represented in a book like this have many sources, and it is impossible to acknowledge —

or even remember — them all. I have never been comfortable with the idea of ‘intellectual property’,

as ideas can never be owned, but are shared, and are constantly being reconstructed in dialogue with

a wide range of people. This book has been influenced by a large number of colleagues, friends,

students, community workers, activists and authors at various times stretching back over more than 40

years of involvement with community work. I began working on the first edition of this book some 20

years before the publication of this fifth edition, so there have been many influences on its ongoing

development. The book has been an evolving project, and many people have, knowingly or otherwise,

contributed to it along the way.

‘There are some people who have contributed significantly to this book, and who need special

acknowledgement. First, my wife, Dr Sonia Tascon, has been a continuing source of support and

inspiration at both a personal and an intellectual level; I owe her a tremendous debt, and her presence

in this bookis strong.

It is important to acknowledge Dr Frank Tesoriero, who took over the third and fourth editions of

this book while my academic and practice interests moved more into the field of human rights. I am

grateful to him for undertaking this work, and also feel a sense of sadness that circumstances have

dictated that he can no longer be involved with the project. It is important to point out that this edition

contains only material from the first and second editions (for which I was the sole author) together

with substantial additions and alterations I have made to bring it up to date. It contains none of the

material that Frank added in the third and fourth editions, and hence it is published with my name as

the sole author. I am also gratefull to the many colleagues throughout Australia and overseas who

encouraged me to take up this project again and to commit to a new edition.

Other people I wish to acknowledge, whose influence on the early editions and/or on the present

edition has been particularly important, are, in alphabetical order, Jacques Boulet, Linda Briskman,

Ingrid Burkett, Love Chile, Phil Comors, Jo Dillon, Wendy Earles, Erica Faith, Lucy Fiske, Vic

George, Amanda Hope, Adam Jamrozik, Sue Kenny, Nola Kunnen, Mary Lane, Louise Morley, Robyn

Munford, Rob Nabben, Jean Panet Raymond, Stuart Rees, Gavin Rennie, Monica Romeo, Dyann

Ross, Rodney Routledge, Evelyn Serrano, Pat Shannon, Joanne Stone, David Woodsworth and Susan

Young.

The section in chapter 4, on Indigenous contributions to community development, was read by

Auntie Sue Blacklock, Gillian Bonser, Carmen Daniels, Paula Hayden, Helen Lynes and Cheryl

Kickett Tucker, who provided important feedback. Their contribution is particularly valued.

I wish also to acknowledge the generosity of students and colleagues at the University of Western

Australia, Curtin University, and Victoria University (Melbourne), who over the years have shared

ideas and helped to create enriching climates to explore issues of community development. Beyond

the traditional university, Borderlands Cooperative is a special place of shared scholarship, learning

and activism, with a wonderful community development library, which has provided me with a

particularly stimulating environment in which to develop ideas for this edition. Earlier editions were

particularly influenced by friends and colleagues at the Greens (WA), Amnesty International and the

International Federation of Social Workers.

‘This edition is published by a different publisher, and I am gratefill to Pearson Education for their

generosity in releasing the copyright of the first two editions so that they could be incorporated in this

new edition. I am also grateful to Isabella Mead, publisher at Cambridge University Press, for her

enthusiasm for the project, and her support throughout the process. My association with Cambridge

University Press goes back over 15 years now, and it has been a very professional, positive and

trouble-free relationship that I have come to value highly.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my grandchildren, Ben, Emma, Joe, Hamish and Phoebe. It is, I

hope, a small contribution towards creating a better future for them and for all those who will inherit

the world that my generation has so comprehensively trashed and stripped of its communitarian

traditions.

Jim Ife

Melbourne, 2013

Introduction

Despite the formidable achievements of modern, Western, industrialised society, it has become

clear that the current social, economic and political order has been unable to meet two of the

most basic prerequisites for human civilisation: the need for people to be able to live in

harmony with their environment, and the need for them to be able to live in harmony with each

other. If these two needs cannot be met, in the long term, the achievements and benefits of

modern society will be transitory.

The inability of the dominant order to meet these needs can be seen in the crises currently facing

not only Western industrialised societies but all societies. The world is characterised by

increasing instability — whether ecological, economic, political, social or cultural — and existing

institutions seem only able to provide solutions which in the long term, and even in the short

term, only make things worse.

Those were the words that introduced the first edition of this book, published in 1995. Eighteen years

on, they are as true today as they were then, if not more so, and the justification for this book remains

the same. Many things have changed in those 18 years, but the above paragraphs also remind us that

many things — the most important things — have not. The world is still on a course that is headed for

major crises — environmental, economic, social and political — and despite the fact that many more

people are now aware of, and concerned about, the parlous state of the world and its very uncertain

future, governments are still showing themselves unwilling or unable (or both) to do anything

significant about it. There have been great disappointments in those 18 years: the failure of the

Copenhagen summit on climate change in 2009, the inability to respond to the Global Financial Crisis

in any way except by bailing out the banks and propping up global capital, the resulting austerity

measures, the draconian response to the threat of terrorism since ‘9/11°, which has served only to

heighten global tensions and make a terrorist response more likely, ongoing tension and conflict in the

Middle East, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as continuing conflicts in parts of Affica, the

widening gap between the increasingly wealthy global elite and the rest of the world, the inability to

meet the modest Millennium Development Goals, the hardening of attitudes towards refugees and

asylum seekers, the emergence of right-wing and racist political groups in many countries. These

suggest that the current structures of national and global government are utterly unable to meet the

pressing global problems that threaten the future of human civilisation. The words that immediately

followed the above 1995 passage — ‘In this context, the need for alternative ways of doing things

becomes critical’ — now seem almost an understatement.

There are, however, signs of hope. The continuing demonstrations against globalisation,

culminating in the Occupy movement of 2011, suggest that there are many people who are seeking an

alternative. The widespread disillusionment with mainstream political parties, caused by the

perceived irrelevance of mainstream politics and meaningless elections that fail to address many of

the major issues facing the world, can also lead to people seeking a new form of politics, although it

is yet unclear how this will evolve. Social media and the internet have made possible the

documentation of human rights abuses and the mobilisation of opposition in the so-called Arab Spring

and in other protest movements. Campaigning groups such as GefUp! and Avaaz have successfully

mobilised large numbers of concerned people to oppose oppressive legislation or to struggle for

environmental and social justice, Latin American social movements and progressive governments

have been developing inspiring commmmity-based alternatives: the Zapatistas in Mexico, the

community response to the oil crisis in Cuba, the popular governments of Chavez in Venezuela and

Morales in Bolivia, the education demonstrations in Chile, the ‘horizontalidad’ movement in

Argentina. Despite their inevitable problems, facing the hostility of global capital and conservative

media interests, these represent bold initiatives towards an alternative future that are an inspiration to

the world.

It is in this context, both of impending crisis and of new signs of hope, that commmnity

development can play a crucial role. There has been increasing interest in development at the

community level as potentially providing a more viable and sustainable basis for the meeting of

human need and for interaction with the environment, and it is not surprising that the Latin American

examples above all include a strong component of alternative commmity development. Among

activists concerned with both environmental and social justice issues, the establishment of viable

community-based structures has become a key component of strategies for change. Community

development represents a vision of how things might be organised differently, so that genuine

ecological sustainability and social justice, which seem unachievable at global or national levels, can

be realised in the experience of human community. This book represents an attempt to articulate that

vision, and to provide a theoretical framework for commmmity development that will relate analysis,

context and action.

In the years since the first edition, the organisational context of practice, dominated by

managerialism, has become less conducive to good community development, as discussed in chapter

15, but nevertheless the need for, and the continuing interest in, community development remains

strong, This is particularly so among those concerned for social justice and ecological sustainability,

as community development is seen as a potential alternative way to organise human society; if indeed

there are to be economic, political and ecological crises, as now seems inevitable, it will be our

ability to work at community level that will determine the capacity of human civilisation to survive.

However, the interest in community development is also driven by a belief that human community is

important, and that strong communities will enrich our lives and provide a positive context for human

interaction and for the meeting of human need, especially given the continuing erosion of the welfare

state.

‘This ongoing interest in community devel opment is shown by reaction to the earlier editions of this

book, which have had a wider appeal than first imagined. This wider appeal has been evident in two

directions. One is the embracing of community devel opment by a wide range of occupational groups,

not merely the human-service professionals and community activists that one might expect, and who

were implicitly the readership for which the first edition was intended, I have discovered a much

broader range of occupational and interest groups who feel that community development is important

in their work, and this has underscored the power of the comnumity development perspective. The

other is the way the book has been found usefull in different cultural contexts. Although the book is

written from the perspective of a white Australian male, earlier editions have resonated with workers

in different cultures, and it has been translated into several different languages. This inevitably raises

questions about colonialism, a topic that is covered in chapter 9, but it also emphasises that the

concerns of community devel opment are universal, and many of the broad principles discussed in this

book (such as wisdom from below, the importance of process, interdependence, participation,

empowerment and so on) apply across cultural boundaries, although the way they are constructed and

applied will differ significantly in different contexts.

For readers familiar with earlier editions, it is important to outline some history of this publication

to avoid any confusion as to authorship. This is the fifth edition of this book, although it is the first to

be published by Cambridge University Press. Iwas the sole author of the first two editions (1995 and

2002), but the third and fourth editions were prepared by Dr Frank Tesoriero; our names appeared as

joint authors for the third edition (2006), and he was the sole named author of the fourth edition

(2010), although much of the content was continued from the earlier versions. Sadly, Frank is no

longer associated with the project, and this current edition contains none of the material he added for

the third and fourth editions. It does contain material written for the first two editions, together with a

good deal of new material; there are 16 chapters, compared with 11 in the first edition and 12 in the

second. However, the overall trajectory of the book remains the same.

‘The first five chapters lay the foundation for a vision of community development, Chapter 1

examines the crisis of modern Western societies and the crisis of the welfare state, and argues the

need for community development. Chapter 2 explores the ecological crisis and its imperatives, in the

light of Green political theory, developing an ecological perspective for community development.

Chapter 3 outlines a social justice perspective, including discussion of rights, needs, equity, justice,

empowerment and so on. It explores issues of class, gender and race/ethnicity from both structural

and poststructural perspectives. Chapter 4 outlines elements of a post-Enlightenment position,

including ideas of postmodernism and relational reality. A particularly important section of this

chapter discusses Indigenous cultures, and the significant contributions they can make to community

development, Chapter 5 then seeks to integrate the perspectives of the previous three chapters, in a

vision for community development and for community-based human services.

‘The next two chapters explore two significant principles of community development. Chapter 6 is

concerned with change from below, valuing the wisdom, expertise and skills of the commmity, and

the importance of decentralisation and community control. Chapter 7 discusses the processes of

community development, including the primacy of process over outcomes, and the issues of

participation, democracy, consciousness-raising, peace and non-violence.

Chapters 8 and 9 outline a more global, or international, perspective. Chapter 8 is concerned with

globalisation and understanding commmity development in a globalising world, while chapter 9

explores the important issue of colonialism, which can affect all community development practice,

and considers issues around working internationally.

Chapters 10 and11 outline eight dimensions of commmity development: social, economic,

political, cultural, environmental, spiritual, personal and survival. Practice in each of these eight

areas is discussed, with various issues identified in relation to each. The approach taken is one that

emphasises the importance of all eight, in a holistic and integrated understanding of what community

development means

Chapter 12 seeks to summarise the ideas of previous chapters in a series of practice principles.

‘There are 30 principles discussed altogether and, although there is little in this chapter that has not

been covered in previous chapters, readers have found such a summary at this point to be particularly

usefill as a way of encapsulating the principles of community devel opment.

‘The remaining chapters are concerned with issues of practice. Chapters 13 and14 discuss the

various roles taken by community workers, and identify the skills needed to fill those roles. In doing

so they discuss issues of practice/theory, the problems with prescriptive ‘cookbooks’, and the ways

in which community workers can develop their skills. Chapter 15 is concerned with the managerial

environment in which many community workers have to practice, and which is hostile to community

development principles. It outlines some approaches community workers can use either to adapt to, or

to directly challenge, managerialism. Chapter 16 discusses a number of other issues relating to

practice, such as professionalism, value conflicts, ethics, support for workers and so on.

‘The book moves, in a general way, from more theoretical to more practical considerations, but it

is far from a simple linear development. Indeed, part of the discussion in the earlier chapters

emphasises the need to reject linear thinking, so the reader is encouraged to ‘jump around’ and not

necessarily read the book in the order in which it is written, The book does attempt to follow a

logical sequence, but there are other equally valid logical sequences that could have resulted in a

very different order of the material.

Although I have attempted to make the ideas accessible to a wide readership, it has been necessary

to make some assumptions about the background of those for whom the book is written. I have

assumed that the reader has some familiarity with basic social and political ideas, such as social

class, power, the division of labour, Marxism, feminism, socialism and so on. This is not to say that

detailed or expert knowledge of such topics is necessary; completion of first-year university study in

sociology, anthropology, politics or some other social science discipline, or alternatively a

comparable understanding gained from general reading, should provide the reader with a more than

adequate background.

Ihave updated the references to incorporate contemporary sources; a lot has been written since

1995. However, I have also included a number of older sources for the earlier editions where I

believe they have something important to say. In this age when the ‘here and now’ is so valued, and

where history is often marginalised, it is important that we challenge this by listening to the voices of

the past as well as the present, and there is much of value to community development in earlier

literature.

‘This book makes frequent use of a number of terms that have been grossly overused and misused in

recent years, such as community, empowerment, development, sustainable, ecological, Green,

social justice, community-based, holistic, participation, consciousness-raising, non-violence, and

participatory democracy. Although these terms have been overused, they still represent powerful

ideas; indeed, their very popularity is a testament to their power and their perceived relevance. They

have an important contribution to make to the vision and the practice principles of this book the aim

of the book is to clarify rather than obscure these ideas, and to reinvest them with some substantive

meaning for community workers.

Throughout the book, the terms community development andcommunity work have slightly

different meanings. I have used the former to refer to the processes of developing community

structures, while the latter refers to the actual practice of a person (whether paid or unpaid) who is

consciously working to facilitate or achieve such development.

Ihave opted for the most part to use the terms the South and the North rather than developing

nations, Third World or other similar terms and their opposites. None is wholly satisfactory, and

living in Australia the South offends one’s geographical consciousness but, as in other ways it is the

least offensive term, it is the one I have chosen. The term Western (or the West) similarly takes

liberties with geographical principles, particularly for an Australian. The term is nonetheless a useful

one, and in the context of this book it refers primarily to Western culture, whereas the terms North

and South are used more in an economic context; of course the distinction is not always clear-cut, as

economics and culture are themselves inextricably entwined. It should, however, be noted that there

is no necessary single antithesis of Western in cultural terms, whereas the economic constructs of the

North and the South are not only opposites but also in such a structural relationship that neither could

exist without the other, and each serves to define the other. Ihave used the term Aotearoa rather than

New Zealand, as a deliberate political and cultural statement; I only wish that Australia had a

similarly accepted Indigenous name

Throughout the book there are a number of tables and diagrams that illustrate in summary form the

ideas discussed in the text, culminating in figure 16.1 (see page 366), which ambitiously attempts to

summarise the entire framework. They are included with mixed feelings: several readers have

commented that such tables and diagrams are helpful in obtaining an overview and in seeing how the

material fits together, but this needs to be balanced against the dangers of categorisation and

oversimplification. Tables and diagrams can have the effect of imposing a false sense of order on a

complex and chaotic reality and, hence, of inviting simplistic solutions to complex problems. To

represent complex concepts by a few words in a cell of a table is to change the very nature of the

content itself, and invites a dangerous reductionism. A too-rigid interpretation of such tables is

antithetical to the holistic approach advocated in the early chapters, and the reader is cautioned to

remember that the boundaries of the tables do not represent rigid distinctions or impermeable

barriers. If the tables and diagrams are regarded as an aid to comprehension but not as rigid

categorisations or definitions, they will have served their purpose.

While this book has a practical application, and attempts to incorporate both theory and practice, it

does not provide simple prescriptions of how to ‘do’ community work. The reasons for rejecting such

an approach are given in chapter 13. A number of principles of practice are outlined, but the way in

which they are translated into practice reality will vary from community to comity, and from

worker to worker. Commmity work is, at heart, a creative exercise, and it is impossible to prescribe

creativity. Rather, one can establish theoretical understandings, a sense of vision and an examination

of the nature of practice, in the hope that this will stimulate a positive, informed, creative, critical and

reflective approach to community work. That is the aim of this book

1 The crisis in human services and the need for community

‘There is no clear agreement on the nature of the activity described as community work. Some see it as

a profession; some see it as one aspect of some other profession or occupation such as social work or

youth work, some see it as anti-professional; some see it as people coming together to improve their

neighbourhood; some see it in more ambitious terms, of righting social injustice and trying to make the

world a better place; some see it in terms of social action and conflict; some see it in terms of

solidarity, cohesion and consensus; some see it as inherently radical; some see it as inherently

conservative; and so on (Butcher et al. 2007, Chile 2007b, Kenny 2010, Ledwith 2005, Craig, Popple

& Shaw 2008). Not only do people's understandings of community work differ but also the

terminology is similarly confused, The terms community work, community development, community

organisation, community action, community capacity-building, community enterprise, community

practice andcommunity change are all commonly used, often interchangeably, and although many

would claim that there are important differences between some or all of these terms, there is no

agreement as to what these differences are, and no clear consensus as to the different shades of

meaning that each implies.

There is similar confusion about the idea of community-based human services. The term

comiaunity-based is used in a variety of contexts, and often has little substantive meaning beyond a

vague indication that the service concerned is somewhat removed from the conventional bureaucratic

mode. There is, however, considerable interest in the development of a community-based approach to

the delivery of human services such as health, education, housing, justice, childcare, income security

and personal welfare, and a belief that this represents an important improvement over the current mix

of welfare state and private market (De Young & Princen 2012, Clark & Teachout 2012).

This book is an attempt to make sense of community work and community-based services. It is

based on the premise that the main reason for much of the confuusion, and the seeming inadequacy of

what passes for community work ‘theory’, is that community work has often not been adequately

located in its social, political and ecological context, or linked to a clearly articulated social vision,

in such a way that the analysis relates to action and ‘real-life’ practice. Many of the stated principles

of practice are fragmentary and context-free, and often the goals of commmmity work remain vague,

uncharted and contradictory. Similarly, the literature on community-based services is often rhetorical

rather than substantive, and often does not relate specifically to relevant social and political theory.

‘This book attempts to remedy that deficiency. It seeks to locate community work and community-

based services within a broader context of an approach to community development. This latter term is

seen as the process of establishing, or re-establishing, structures of human community within which

new, or sometimes old but forgotten, ways of relating, organising social life and meeting human need

become possible. In this context, community work is seen as the activity, or practice, of a person who

seeks to facilitate that process of commumity development, whether or not that person is actually paid

for filling that role, Community-based services are seen as structures and processes for meeting

human need, drawing on the resources, expertise and wisdom of the community itself

‘The starting point for this exploration will be the crisis in the contemporary welfare state and the

emergence of neo-liberalism, alongside the recurring interest in developing some form of

“community-based? alternative. It is from examining the shortcomings of many attempts to move to a

community-based model, and the identification of what is missing from these attempts, that the vision

ofa more viable alternative can begin to emerge.

The crisis in the welfare state and the emergence of neo-liberalism

Contemporary community work must be seen within the context of the crisis in the welfare state, and

the erosion of government and popular support for continued growth in welfare state provision. The

crisis in the welfare state became evident in the 1980s, as the ‘new Right” ideology and economic

theory of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher began to influence government policy and public

opinion. This was the beginning of the era of neo-liberalism, an ideology that had its origins in the

philosophy of Friedrich Hayek and the economic theory of Milton Friedman, emphasising the primacy

of individual freedom and the superiority of the private market as the best way to allocate wealth and

resources. In such a world view, public, or state, provision plays a secondary role, and indeed should

be reduced to a minimum. The belief in the superiority of the unregulated market and private initiative

leaves little room for the state.

This ideology challenged the previous ‘postwar consensus’, which defined a central role for

government in the meeting of human need and the creation of a fairer society. This earlier view was

exemplified by the Beveridge Report in Britain, which laid the foundation for the postwar British

welfare state, and the social policy writing of Richard Titmuss and T-H. Marshall. Similarly Franklin

D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ in the USA in the 1930s had identified a strong role for government in

lifting the nation out of economic depression, Welfare states were also established in most European

countries following World War IL, and in other so-called developed nations (such as Canada,

Australia and Aotearoa) whose economies were able to afford significant public expenditure on the

provision of health, education, housing, income security and personal services. These welfare states

took different forms — some were more extensive and well developed than others, and some were

more dependent on a social insurance model — but they all accepted the notion that a major role of

government was to provide for the needs ofits citizens.

This view was challenged by neo-liberalism, which emphasised the importance of individual

responsibility rather than state provision, and saw government’s role as to support the market and to

“get out of people’s lives’ (Harvey 2005, Saad-Filho & Johnston 2005, Honeywill 2006, Beder 2006,

Beck 2012, Kempf 2009, Panitch & Gindin 2012). Under neo-liberalism, the termnanny state

became a popular epithet for the criticism of the idea of a welfare state, and government expenditure

moved from being seen as positive, enhancing the common good, to being seen in negative terms as a

drain on the productive economy; governments were elected on promises to do less rather than more,

and to reduce taxes rather than to expand services. In this context, it has become common for many

commentators to deride a ‘culture of entitlement’ and to encourage individual autonomy and

‘independence’ (we shall see in later chapters that ‘independence’ is a nonsense). With the end of the

Cold War around 1989, and the consequent delegitimising not only of communism as it had been

manifest in the Soviet bloc but also of Marxism more generally, and even of socialism, there was no

effective opposing ideology to capitalism, and so neo-liberalism — essentially an extreme form of

unregulated capitalism — could reign supreme (Harvey 2005). This, of course, has exacerbated

economic inequalities, as the welfare state and strong government regulation — mechanisms for

reducing inequality and ensuring a reasonably equal sharing of available wealth and opportunity —

were simply not available. Neo-liberalism, indeed, accepts inequality as both necessary and

desirable, if economic growth and individual prosperity are to be maximised.

Since the arrival of neo-liberalism as a mainstream ideology, it has become clear not only that the

welfare state is unable to meet fully the needs of citizens but also that there is a strong belief among

many political and opinion leaders that it should not attempt to do so, as this would reduce incentive

and encourage ‘dependency’. But neo-liberalism is not alone in its criticism of the welfare state.

There is now almost complete agreement about the inadequacy, instability and uncertainty of the

contemporary welfare state and its apparent continuing inability to meet the full range of human needs.

Even critics from the political Left have been forced to admit that a centralised welfare state is

unable to meet all our social needs, and can be dehumanising and alienating because of its inhumane

bureaucratic structures.

One of the important characteristics of neo-liberalism is that its emergence coincided with, and

embraced, globalisation. This became possible initially because of the increased availability of

global travel and then with the coming of the computer age and the possibility of instant

communication on a scale previously unimaginable, making possible new global networks of power

(Castells 1996, 1997, 1998), Hence neo-liberalism became a global force, and the markets became

globalised, and were thus beyond the capacity of national governments to regulate, even if they had

wished to. Governments had to take careful note of the requirements and preferences of global

markets, if they did not want to face sudden and dramatic withdrawal of capital and corresponding

economic collapse. What became known as ‘globalisation’ was effectively the globalisation of the

economy and of markets, together with a form of ‘cultural globalisation’ so that the purchasing

choices of consumers became as similar as possible (e.g, in clothes, entertainment, food, cars, etc.)

(Niezen 2004, Castells, Caraga & Cardoso 2012); it is easier to produce for a market if everybody

wants to buy more or less the same things. We did not see a corresponding globalisation of social or

environmental concerns. This difference is seen in the relative lack of mobility of labour as opposed

to the instant mobility of capital, and the strength and power of those international mechanisms

established to serve the global economy (e.g. the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World

Trade Organization), compared with the weakness of international structures (through the United

Nations or international NGOs) to achieve social justice or environmental sustainability at a global

level (Beder 2006, Satz 2010). Globalisation will be discussed in more detail in chapter 8.

‘The effects of the crisis in the welfare state and the rise of neo-liberalism are clearly visible at the

level of service delivery. Continuing cutbacks in public services, lowering of the quality of service

as overburdened workers are urged to ‘do more with less’, longer waiting lists and waiting periods,

lack of access to health care (except for those who can afford private insurance), the deterioration of

the public education system, poor staff morale, and a general lack of confidence in the capacity of the

public system to cope, are all familiar themes in many Western societies. Policy responses have

tended to reflect neo-liberal orthodoxy, through privatisation, the creation of quasi-markets (e.g, in

health care with different ‘providers’ competing with each other), the role of government as a

purchaser of service rather than as a provider, and encouraging the private sector to be involved

either through public/private ‘partnerships’ or through total privatisation and the principle of ‘user

pays’. Other policy options, requiring increased taxation and spending, are simply unacceptable in the

neo-liberal world.

‘The neo-liberal perspective is not always readily accepted by the people, as can be seen in the

reactions of people in the European region to the ‘austerity measures” imposed on them by neo-liberal

orthodoxy following the Global Financial Crisis (Castells, Caraga & Cardoso 2012). In this regard,

the people of Europe are sharing the experience of the people of other regions, such as Latin America

and Africa, who have had to face the hard edge of neo-liberal policies for decades (Klein 2007).

Hence many governments feel powerless to address significant problems — from unemployment and

substance abuse to climate change and land degradation — while still retaining some measure of

popularity with voters. One consequence can be the substitution of public relations spin for policy,

and several policy techniques have become depressingly familiar as strategies to give the impression

that much is being achieved, One is the production of glossy publications full of rhetoric about ‘steps

forward’, ‘new initiatives’, ‘social advantage’, ‘social dividend’, ‘equity and access’ and other high-

minded goals. Another is an apparently perpetual succession of task forces, working parties, summits

and commissions, which can take up a good deal of time while giving the impression that ‘something

is being done’. A third is organisational restructuring, which is a time-honoured way of appearing to

take ‘decisive action’. A fourth is the repackaging of already existing programs under new, catchy

titles; publications about ‘family policy’, for example, are notorious in this regard. Thus, if one asks a

government representative about the policy on a particularly problematic issue (e.g. domestic

violence, youth homelessness or unemployment), one is likely to be handed a slick publication full of

rhetoric, and to be told about a significant new task force that has been established to deal with the

problem, within a newly restructured government department. Such responses have become apologies

for genuine policy, and represent a tacit admission that many of the problems with which governments

are required to deal are in fact insoluble within existing social, political and economic constraints.

‘The situation is indeed grim, with inadequate human services, rising inequality and a declining

resource base, made worse by the economic instability now affecting or threatening most countries in

the ‘developed’ West. Various alternatives have been proposed by those concerned for social justice,

the three most common being: (1) seeking to defend and re-establish the welfare state, (2) moving

towards a more ‘corporatist’ state, where a consensus is sought between the various interests such as

capital and labour, and (3) a more radical socialist alternative with human need being given highest

priority, bolstered by a strong regulatory state. Each of these has some advantages, but they also have

significant drawbacks and seem to have little likelihood of success in the current social, economic

and political context.

Defenders of the welfare state have found it difficult to counter the criticism that large, centralised

bureaucratic structures, which seem to be an inevitable consequence of a traditional welfare state

system, are neither effective nor efficient in the delivery of human services, and that they dehumanise,

alienate and disempower those whom they purport to serve. In addition, the weak theoretical

foundation of the social democratic approach to welfare (Taylor-Gooby & Dale 1981) has left the

advocates of the welfare state open to attack from both the Right and the Leff; it can be argued that it

was only in the era of the postwar consensus that the ideological foundations of the welfare state

could remain intact, and this consensus has long gone.

Corporatism is subject to significant criticism on the grounds that it represents an artificially

manufactured compromise between essentially competing interests, such as capital and labour, so that

at best it can be only a short-term and inevitably unstable arrangement. It can, perhaps, succeed only

under certain specific economic and political conditions (e.g, relatively stable economic growth and

prosperity), which cannot be expected to last indefinitely. Another criticism of the corporatist

approach is that it requires trade-offs to be made at the level of peak organisations representing

particular sectors of society and the economy. This militates against democratic or participatory

forms of policy- and decision-making, and serves to reinforce the power of existing elites.

‘The socialist alternative, while arguably resting on a much stronger theoretical and intellectual

base than the other approaches, also fails to take account of the alienating and dehumanising effects of

state bureaucracies and central planning. Despite the rhetorical ideals of a truly socialist society, the

imposition of communism in practice has been accompanied by extremely repressive measures.

While it can be argued that this need not be the case, the experience makes it difficult for Marxists to

gain significant legitimacy within contemporary social and political debate. As will be evident in the

following discussion, a Marxist analysis has much to offer in developing an alternative, but the

classical Marxist solution of state socialism does not seem a credible alternative at this time.

‘The problems of these responses have been exacerbated by the success of neo-liberal ideology in

dominating public discourse. Neo-liberalism is presented as natural, and it is assumed that indeed

there is no practical alternative. Thus it has come to be regarded by many people as the natural order

of things, and the role of governments has been reduced to one of managing and supporting the

capitalist system, rather than seeking alternatives. Government intervention in the market is assumed

to be negative, hence any proactive government policy is viewed with a mixture of scepticism and

alarm, as is only too clear to those who have so desperately sought government action to avert serious

climate change.

A way forward

The above very complex issues deserve more thorough treatment than can be covered here. The

purpose of this quick — and inevitably superficial — discussion is simply to highlight some of the

specific objections to each of the three conventional responses to the crisis in the welfare state and

the emergence of neo-liberalism. For the purposes of this book it is significant to concentrate on one

overriding objection to all the above responses to the crisis, which can be summarised as follows:

The crisis in the welfare state, and the tragedy of neo-liberalism, are the result of a wider

crisis of a social, economic and political system which is unsustainable, which has reached a

point of ecological crisis, and which is only exacerbated by the neo-liberal agenda. Each

conventional response to the crisis in the welfare state and the emergence of neo-liberalism

is itself based on the same unsustainable, growth-oriented assumptions, and is therefore itself

unsustainable.

This objection to the traditional policy responses to the crisis in the welfare state and to the

emergence of neo-liberalism is the basis for the remainder of the book, which aims to develop an

alternative approach to human service policy and practice that is more consistent with a truly

sustainable society. Therefore it is appropriate to consider this objection in more detail.

As Marxist writers have pointed out since the 1970s (e.g, O’Connor 1973, Offe 1984), the welfare

state has grown alongside industrial capitalism, and must be seen as an integral part of the existing

social, economic and political order. The state provision of such public services as health, education,

housing and welfare has not been simply the result of altruistic views of benign and caring

governments but has been necessary in order for industrial capitalism to grow and flourish, and as a

means of establishing and maintaining social control. The Marxist analysis has been particularly

significant in demonstrating this, and sees the welfare state as being in a symbiotic relationship with

advanced capitalism: each is necessary for the other’s survival. Thus modern capitalism would not be

possible without some form of welfare state in order to meet human need, to maintain stability and

security and to keep the workforce healthy, happy and ‘appropriately’ educated so that the key

processes of production and reproduction can be maintained (George & Wilding 1984).

Such an analysis, which developed in the social policy literature of the 1970s and 1980s, before

the fill emergence of neo-liberalism, means that the welfare state must be seen within the context of,

and not as separate from, advanced capitalism, While capitalism, in its present form, cannot survive

without some form of welfare state, the corollary is that the welfare state in its present form cannot

survive without the industrial capitalist economic order within which it has developed. There is now

ample evidence that this existing order is unsustainable, as the contradictions of the system (of which

the contradictions of the welfare state are only a part) become more apparent (Homer-Dixon 2006,

Castells, Caraga & Cardoso 2012). The system is based on continued growth, which is having

disastrous effects on the global environment. As the ecological and human costs of continuing growth

and ‘progress’ become more evident, and as the warnings that the global industrial and economic

system is reaching the limits to growth are more clearly recognised (Shiva 2005), the urgency of the

situation is highlighted. Western governments are finding it increasingly difficult to sustain economic

development, standards of living and full employment (by whatever statistical artifice that is

measured). The conventional economic solutions do not seem to work very well, and are at best short

term. The inequities and limits of the global economic system, to which all Western economies are

now inextricably linked, are becoming more apparent. Increasing numbers of economists and other

commentators are reaching the conclusion that the major economic and social problems facing

modern society can no longer be solved from within the existing system, and that a radical change is

necessary —to a quite different society, based on different economic principles (Quiggin 2012, Ekins

& Max-Neef 1992, Doorman 1998, Greco 2009, Boulet 2009, Honeywill 2006). This change would

clearly include the welfare state.

‘The argument thus far is in many ways consistent with a Marxist analysis; indeed, Marx and his

successors have clearly identified the contradictions of capitalism, and have similarly suggested the

need for a radical reformulation, However, there is a findamental difference between the Marxist

position and the alternative “Green” position on which this book is based. Marxists have still assumed

that continuing economic growth, with a corresponding increase in productivity, wealth and personal

income, is not only possible but also desirable (and, one might argue, necessary). In this they are in

agreement with other ideological positions, including both neo-liberalism and social democracy. Itis

common in elections to hear parties from many differing ideological positions, including the Leff,

assuming that the way out of current economic problems is to step up economic growth and to argue

about the best way this can be achieved, Over the years, in a remarkable case of language slippage,

the idea of ‘sustainable development” coined in 1987 by the Brundtland Commission (World

Commission on Environment and Development 1987) has morphed first to ‘sustainable growth’, then

in the Rio ‘Earth Summit’ of 2012 into ‘sustained growth’. An alternative ‘Green’ position, however,

maintains that economic growth is at best a doubtful benefit, in that it causes more problems

(including environmental, social and economic problems) than it solves. Indeed, in a finite world, it

is clearly ludicrous to assume that growth can continue indefinitely, and there is a growing body of

evidence to suggest that the effective limits to growth are being reached (Hamilton 2003, De Young &

Princen 2012).

It is thus necessary to seek a system that breaks the cycle of growth and is not dependent on

continuing growth for its maintenance (in contrast to the existing form of industrial capitalism, as well

as the Marxist socialist alternative). This requires a genuinely ecological perspective incorporating a

notion of sustainability, and this will be explored in chapter 2. It is worth noting, however, that in this

context sustainability represents a more significant departure from existing practices than is implied

by many contemporary politicians and public figures, given the current trend to justify virtually any

policy under the now almost meaningless term ‘sustainable development’, or the blatantly self-

contradictory ‘sustainable growth’.

From this perspective, the crisis in the welfare state cannot be satisfactorily resolved using any of

the four policy strategies outlined above. The existing growth-oriented social, economic and political

system, within which the welfare state is located, is clearly unsustainable in anything other than a

very short time span. The welfare state, certainly in the form to which we have become accustomed in

the West, seems unlikely to last much longer, and as the structures of society change (as from the

ecological perspective they nuist), different structures and services for the meeting of human need

will have to be developed. This should not be a surprising conclusion: the modern welfare state,

although its origins can be traced back several hundred years (de Schweinitz 1943), is essentially a

creature of the twentieth century and of the affluent West. Throughout all but a hundred years of

history the human species has been able to survive without the welfare state, and even in this hundred

years its supposed benefits have been enjoyed by only a minority. The welfare state is not a

permanent fixture, nor is it necessarily a natural component of human civilisation.

Community-based services as an alternative

‘Throughout history, there have been different institutions and mechanisms for the meeting of human

need. At different times and in different contexts the extended family, the tribe, the village, the

Church, the market and the state have all been seen as playing critical roles in this process, often in

combination. Each institution has had a dominant role in the meeting of need, yet as society has

changed each has proven to be by itself inadequate for the needs of the new order, although each has

retained a lesser role in subsequent times. The crisis in the welfare state is simply another of these

historical transitions, where the nation state, for which such great hopes were held, is demonstrating

its inadequacy as new forms of social, economic and political structures emerge.

From this perspective it is inappropriate to put too much energy into defending or strengthening the

welfare state. A more useful direction is to ask what might be an alternative form of social provision

that would be consistent with the newly emerging social and economic order. Many of the policy

prescriptions that enjoy contemporary popularity represent an attempt to reinstate some of the earlier

forms of the meeting of need, principally through the market and the family. Historically, the

limitations of both of these have become apparent, and are even more evident within the

contemporary social and economic system, where the market is again proving its inadequacy to meet

human need equitably, and where the family is under continuing pressure and is increasingly

fragmented (Jamrozik & Sweeny 1996); there is a crisis in the institution of the contemporary family

that renders it utterly incapable of meeting the demands of social care with which some seek to

burden it.

Within this context, there is an increasing interest in community-based programs as an alternative

mode for the delivery of human services and the meeting of human need (Wheatley 2009, Wheatley &

Frieze 2011, Ball 2011, Bauman 2001, Block 2009, De Young & Princen 2012, Clark & Teachout

2012). After the family, the Church, the market and the state, it may now be the turn of the

‘community’ to carry major responsibility for the provision of services in such fields as health,

education, housing and welfare. The idea of commumity is a central theme in much of the Green

literature (Hopkins 2008, Pahl 2007, Vanclay 2006, Harding 2011, Manzini 2011, Wheatley 2009),

and at first sight it may seem that a community-based approach to human services is consistent with

the idea of a ‘post-welfare state’ system based on principles of sustainability. Later chapters in this

book will explore the potential of such a community-based approach as the next stage in service

provision ‘beyond the welfare state’, and will discuss how such a system might operate and what it

would mean for those ‘doing’ community work.

As already noted, the terms community and community-based are highly problematic, and mean

different things to different people. The approach to community work and commmmity-based services

developed in this book is not necessarily consistent with the frequent usage of the terms in

government policy discourse, where they have come to have as little substantive meaning as the word

sustainable. Before outlining the community development approach on which this book is based, itis

necessary first to identify some of the significant problems often associated with approaches to human

services that are labelled ‘commmity-based’. Only then will it be possible to attempt to develop an

approach to community development that overcomes these difficulties and has the potential to become

the basis of a system of human services in a future society based on principles of sustainability.

Problems with conventional approaches to ‘community-based services’

Policies of community-based human services have the potential for both progressive and regressive

change. Although such an approach may provide an opportunity for the kind of radical developments

outlined in later chapters of this book, it has also been criticised for its inherent conservatism, on a

number of grounds. This is not the place to explore these criticisms in detail, yet they need to be

summarised and specifically acknowledged. Later chapters seek to describe an approach that

overcomes these objections to community-based social provision.

1 Reducing the commitment to welfare

In an era when governments are seeking to reduce expenditure on human services, community-based

programs provide an expedient way for this to occur, and represent a form of ‘services on the cheap’.

This is particularly true of the move from institutional care to community care, where the high costs of

institutional care can be reduced, but it is also true of other ‘community-based’ options, in that they

tend to rely more on the use of volunteers and on staff who are paid lower wages than those in the

public sector. The practice of tendering, increasingly popular with governments, can lead to a ‘race to

the bottom’ where agencies try to outbid each other as to which can provide the cheapest service.

Such cost-cutting is a frequent result of moving to community-based services, and has a tendency to

become the de facto justification for such a move.

In addition, for a government intent on cost-cutting, it is often easier to reduce funding for

community-based programs than to reduce funding for an equivalent service provided by the state.

This is because the hard decision to reduce services is made at community level, usually by a local

management committee, so it is not as readily seen as the fault of the government, even though it

directly flows from a reduction in government funding. The community management committee can in

this way easily be set up as the scapegoat for the withdrawal or reduction of public services

Thus community-based services can readily serve the political agenda of a government that is

committed to reducing public expenditure, and can facilitate the reduction in the share of the nation’s

wealth going to human services.

2. Covert privatisation

Another way in which community-based services can serve a conservative political agenda is by

providing a rationale for the withdrawal of government responsibility and a corresponding move to a

market-based approach. By simply withdrawing from service provision, loosely using the thetoric of

“community responsibility’, a government can allow the private market to move in to fill the gap. This

can result in a community-based project being operated by a market-driven philosophy with the goal

of maximisation of profit rather than the meeting of human need, Thus the terms community and

market can become synonymous. This is not necessarily so; the community development approach

outlined in later chapters foresees a reduction in direct government activity but does not imply an

increased reliance on the private market, at least in its large-scale manifestation,

3. The family

Just as the rhetoric of ‘commumity-based services’ can be used as a justification for a retun to

reliance on the market to meet human need, so it can be used to support a system where the family

accepts a greater burden of care; as with privatisation, this is simply seeking to return to an older

form of service provision, which is inappropriate for the contemporary context. Such a trend is

particularly seen in the field of ‘commumity care’. This often does not imply that some form of local

autonomous community will accept responsibility for a person’s care (as would be the case with a

genuinely community-based system), rather that the person concerned will be cared for ‘in the

community’ by members of their nuclear or extended family, usually women. It can therefore have the

effect of placing extra burdens on family members, especially on women, while not acknowledging

the pressures already placed on family structures and the breakdown of the traditional ‘family’ in

contemporary society.

4 Gender

A move to commumity-based services can place a disproportionate burden on women, both because

of their traditional role as primary caregivers and because of the higher level of participation by

women in the community sector. Within contemporary society, strongly influenced by economic

rationalism and neo-liberalism, caregiving and involvement in commmmity activities are not highly

valued, as they are not seen as creating wealth or improving productivity. Hence those who do the

caring are devalued, and community-based services can help to marginalise women and reinforce

dominant patriarchy. As will be discussed in chapter 3, the oppression of women is one of the

fundamental forms of disadvantage in contemporary Western society, and community-based services

need to be designed in such a way that they challenge rather than reinforce this disadvantage

5 The tyranny of locality

Personal mobility is a characteristic of modern Western societies, and it has become accepted, even

valued, that people should travel long distances to meet their needs for social interaction,

entertainment, education, social services and so on. A community-based approach can be seen as

restricting people to their local community when they may prefer to seek man services elsewhere,

either because of a belief that a better service is available in another location or because of a wish

for anonymity and a desire to avoid gossip and intrusive neighbours.

6 Locational inequality

Because some communities are better resourced than others, a move to a commmity-based approach

could simply reinforce existing inequalities between communities, often based on class lines.

Communities with more resources would be able to provide higher levels of service, and

disadvantaged communities might be further disadvantaged by being denied support from a strong

central administration.

The above criticisms of a community-based approach to human services are powerful. Taken

together they suggest that community-based services can be profoundly conservative, and they explain

why a community-based approach has been popular, at least at the rhetorical level, with conservative

governments. While the rhetoric might appear progressive, or even radical, a commumity-based

strategy can be used to reinforce traditional conservative understandings of the family, privatisation,

government cutbacks and class and gender inequalities. It is hardly surprising that some critics have

demonstrated a cynicism about community-based services — at least as understood within

conventional policy discourse — and have been critical of their potential to present a truly radical

alternative.

‘The approach presented in the following chapters seeks to overcome these objections, and to

demonstrate how a community development approach need not be conservative but could challenge

such conservative ideas, and could help to initiate an alternative society based on social justice as

well as on ecological sustainability.

The missing ingredient: community development

‘The criticisms above relate to a strategy of community-based services developed within the existing

social, economic and political order. Such a strategy has a fundamental weakness, namely it assumes

that there is an entity called ‘commmmity’ within which human services can be based, This assumption

is problematic, given the lack of strong commumity structures in contemporary Western society. The

history of industrial society — and indeed of capitalism — has been a history of the destruction of

traditional community structures, whether based on the village, the extended family or the Church.

This has been necessary for the development of industrial capitalism, which has required a mobile

labour force, rising levels of individual and household consumption, increased personal mobility and

the dominance of an individualist ideology. This is even more the case in the current experience of

industrial and postindustrial capitalism, driven by neo-liberal ideology and global markets. While

there remain some elements of traditional community structures, especially in rural areas, and while

some community bonds are maintained through non-geographical commumities (e.g. ethnic

communities), it is nevertheless true that community in the traditional sense is not a significant

element of contemporary Western society, especially in urban or suburban settings.

For this reason, the development of commumity-based structures seems somewhat contradictory,

and it is little wonder that commmity-based services have proven problematic, as suggested by the

criticisms in the previous section. The central issue can best be expressed as follows: how can there

be commumity-based services if there is no community in which to base them? The primary

assumption of community-based services must surely be that there are community structures and

processes that can take over all or some of the responsibility for the provision of human services.

Although for centuries traditional communities performed these roles, more or less adequately, it is

much more problematic in a society where the dominant social and economic order discourages the

establishment of community and undermines community soli darity.

Thus, a strategy of community-based services will not be effective unless steps are taken at the

same time to reverse the trend of the erosion of community structures, which has been an integral part

of capitalist industrial development. Community-based services therefore need to be accompanied by

a program of community development that seeks to re-establish those structures. Such a program goes

beyond the specifics of a particular commuity-based program, such as community-based childcare,

education or health, It needs to encompass all aspects of human activity and interaction, and amounts

to a radical restructuring of society. This might sound like a tall order but, as will be demonstrated in

later chapters, there are grounds for believing that we have reached a point in history where such a

transformation will not only become possible but also in fact be necessary for survival.

The promise of community

Despite the problems associated with commumity development, and the factors working against

community in modern Western societies, the idea of community remains powerful. Many people feel

strongly the oss of community’ or ‘loss of identity’ in modern society, and see rebuil ding community

structures as a priority for the future (Bauman 2001). The power of the idea of commumity has long

been recognised, and is seen in the tendency over the years for governments to use the term liberally

in titles, speeches and so on, often with little substantive meaning, in 1981 Bryson and Mowbray

famously described conmmmity as a ‘spray-on solution’ (Bryson & Mowbray 1981), and this has

resonated with many writers since then. However, despite the problematic nature of the word, the

power of the idea is significant as a basis for the organisation and development of alternative social

and econoniic structures, as outlined in later chapters. It has served as a powerful vision for a number

of writers in the field of commumity work (Block 2009, Butcher 2007b, Ingamells 2009, Ingamells et

al, 2009, Ball 2011, Wheatley 2009, Chile 2007b, Kenny 2010, Campfens 1997, Kelly & Sewell

1988, Craig, Popple & Shaw 2008, Westoby & Dowling 2009, Clark & Teachout 2012).

‘The feeling of loss of community is often interpreted as nostalgia for an ideal that never really

existed, and advocates of community development have been accused of idealising the ‘village

community’ whose reality was in many instances oppressive. This is an important criticism, and it is

essential that the notion of community be based on more substantial grounds than simply an ideal,

even though the power of that ideal, and the importance of vision, must not be underrated. The

chapters that follow seek to provide such a foundation.

Social capital and civil society