Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Torts and Damages

Uploaded by

annesd29Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Torts and Damages

Uploaded by

annesd29Copyright:

Available Formats

Elements of a Wrongful Death Lawsuit

In order to bring a successful wrongful death cause of action, the following elements must be present:

The death of a human being;

Caused by another's negligence, or with intent to cause harm;

The survival of family members who are suffering monetary injury as a result of the death, and;

The appointment of a personal representative for the decedent's estate.

A wrongful death claim may arise out of a number of circumstances, such as in the following situations:

Medical malpractice that results in decedent's death;

Automobile or airplane accident;

Occupational exposure to hazardous conditions or substances;

Criminal behavior;

Death during a supervised activity.

Damages in a Wrongful Death Lawsuit

Pecuniary, or financial, injury is the main measure of damages in a wrongful death action. Courts have interpreted "pecuniary injuries" as

including the loss of support, services, lost prospect of inheritance, and medical and funeral expenses. Most laws provide that the damages

awarded for a wrongful death shall be fair and just compensation for the pecuniary injuries that resulted from the decedent's death. If the

distributees paid or are responsible for the decedent's funeral or medical care, they may also recover those expenses. Finally, a damage award

will include interest from the date of the decedent's death.

Determining Pecuniary Loss

When determining pecuniary loss, it is relevant to consider the age, character and condition of the decedent, his/her earning capacity, life

expectancy, health and intelligence, as well as the circumstances of the distributees. This determination may seem straightforward, but it often

becomes a complicated inquiry, keeping in mind that the measure of damages is actual pecuniary loss. Usually, the main consideration in

awarding damages is the decedent's circumstances at the time of death. For example, when an adult wage earner with dependants dies, the

major parts of the recovery are: 1) loss of income, and 2) loss of parental guidance. The jury may consider the decedent's earnings at the time

of death, the last known earnings if unemployed, and potential future earnings.

Adjustments in the Jury's Award

In a wrongful death action, the jury determines the size of the damages award after hearing the evidence. The jury's determination is not the

final word, however, and the size of the award may be adjusted upward or downward by the court for a variety of reasons. For example, if the

decedent routinely squandered his income, this might reduce the family's recovery. Similarly, the courts will reduce a jury's award if the

decedent had poor earnings, even though he was young, had great potential, and supported several children. At the same time, a jury may

award lost earnings despite the decedent's having been unemployed, if he had worked in the past and if the plaintiff presented evidence of the

decedent's average earnings while employed. If the plaintiff fails to present such evidence of the decedent's average earnings, the court may

set aside the jury's damage award and order a new trial.

Using Expert Testimony to Determine Pecuniary Loss

Plaintiffs are able to present expert testimony of economists to establish the value of the decedent to his family. Until recently, this testimony

was not admissible when a housewife died, but that rule has changed. When the decedent is a housewife who was not employed outside the

home, the financial impact on the survivors will not involve a loss of income, but increased expenditures to continue the services she was

providing or would have provided if she had lived. Because jurors may not be knowledgeable regarding the monetary value of a housewife's

services, experts may aid the jury in this evaluation.

Punitive Damages

Punitive damages are awarded in cases of serious or malicious wrongdoing to punish the wrongdoer, or deter others from behaving similarly. In

most states, a plaintiff may not recover punitive damages in a wrongful death action. There are some states, however, that have specific

statutes that permit the recovery of punitive damages. In states that do not explicitly allow or disallow punitive damages in wrongful death

actions, courts have held punitive damages permissible. An attorney will be able to advise you as to whether your state allows punitive

damages.

Survival Actions for Personal Injury

In addition to damages for wrongful death, the distributees may be able to recover damages for personal injury to the decedent. These are

called "survival actions," since the personal injury action survives the person who suffered the injury. The decedent's personal representative

can bring such an action together with the wrongful death action, for the benefit of the decedent's estate.

In a survival action for a decedent's conscious pain and suffering, the jury may make several inquiries to determine the amount of damages,

including: 1) the degree of consciousness; 2) severity of pain; and, 3) apprehension of impending death, along with the duration of such

suffering.

Getting Help

If a loved one has dies after an accident or injury caused by the negligence or misconduct of another individual, company or entity, you may be

entitled to bring a legal action for wrongful death against those responsible. Especially in light of time deadlines for filing such a lawsuit, you

should contact an experienced personal injury attorney as soon as possible, to discuss your legal rights and your potential case.

Fraud is the intentional deception of another in order to induce that person to act in such a way that the deceived person is damaged in some

way. The specific legal definition varies from state to state, but under Illinois law, the plaintiff must prove the following:

(1) a false statement of material fact was made;

(2) the defendant knew that the statement was false;

(3) the defendant intended to use the false statement to induce the plaintiff to act;

(4) the plaintiff's relied upon the truth of the statement; and

(5) the plaintiff suffered damages as a result of his or her reliance on the statement.

Not only is fraud a criminal offense, but it is also an intentional tort which may entitle the plaintiff to monetary compensation to recover for

their damages caused by the fraudulent activity. The skilled Chicago fraud attorneys at Ankin Law Offices are well-versed inintentional tort law

and can help you recover for any losses you may have suffered as a result of fraud.

Fraud can be committed in a wide variety of settings and situations, including:

Mortgage fraud

Consumer fraud

Insurance fraud

False advertising

Embezzlement, or the taking of money entrusted to another

Forgery of documents and/or signatures

Health fraud, such as the sale of fake medication

Identity theft

Securities fraud

Tax fraud

Investment fraud, such as Ponzi schemes or pyramid schemes

Because a civil action for fraud requires the proof of certain specific elements, it is important to consult with a knowledgeable and skilled

intentional tort litigator like the attorneys at the Chicago area law firm of Ankin Law Offices. Our experienced intentional tort lawyers have

years of experience upon which we can draw in order to best advise you regarding your potential claims of fraud. We have years of courtroom

experience as well, so we can aggressively advocate on your behalf in order to receive a maximum recovery for your losses. Contact one of

our Chicago fraud lawyers for a free consultation to discuss whether you have a cause of action.

Intentional torts are an area of the law not often examined in detail. However, intentional torts, such as false arrest and malicious prosecution,

offer a fascinating look at how criminal and civil litigation overlap and eventually come to terms with each other.

A case based on false arrest and malicious prosecution begins in criminal court. A classic example is the shoplifter who is arrested and

prosecuted by a merchandise establishment. Normally (although by no means always) the criminal complaint for retail theft is signed by the

individual who witnessed the alleged theft. If the criminal complaint is dismissed or if the case goes to trial and the individual is found not

guilty, a cause of action may exist against the merchandise establishment and/or the individual who signed the criminal complaint.

If a civil complaint is filed based on false arrest and malicious prosecution, Illinois law offers several solid defenses, not the least of which is the

Illinois Retail Theft Act. The Illinois Retail Theft Act, discussed below, offers an affirmative defense to merchants accused of false arrest,

although it is not an absolute bar to such a cause of action. Other defenses work in conjunction with the Illinois Retail Theft Act, weaving a web

a legal defenses when criminal charges are made based on solid facts.

Malicious Prosecution is a separate cause of action, and initial criteria necessary to file such and action has fairly recently been modified by the

Illinois courts. This article will review the torts of false imprisonment/false arrest and malicious prosecution, the primary defenses available to

each of these torts and the evolving nature of malicious prosecution claims.

FALSE IMPRISONMENT/FALSE ARREST

To sustain an action for false arrest or false imprisonment, plaintiff has the burden of proving:

restraint or arrest, against plaintiff's will,

caused or procured by defendants

without having reasonable grounds or probable cause to believe that the offense was committed by plaintiff.

Meerbrey v. Marshall Field & Co., Inc., 139 Ill.2d 455, 464, 564 N.E.2d 1222, 1231, 151 Ill.Dec. 560, 569 (Ill. 1990); Davis v. Temple, 284

Ill.App.3d 983, 988, 673 N.E.2d 737, 472, 220 Ill.Dec. 593, 598 (5th Dist. 1996); Hanna v. Marshall Field & Co., 279 Ill.App.3d 784, 790, 665

N.E.2d 343, 349, 216 Ill.Dec. 283, 289 (1st Dist. 1996). reh'g denied, May 21, 1996.

DEFENSES

A. Voluntarily Consent To Confinement.

The alleged confinement must be against plaintiff's will. Lopez v. Winchell's Donut House, 126 Ill.App.3d 46, 49, 466 N.E.2d 1309, 1312, 81

Ill.Dec. 507, 510 (1st Dist. 1984). Voluntary consent to confinement often nullifies false imprisonment. Hanna v. Marshall Field & Co., 279

Ill.App.3d at 790, 665 N.E.2d at 349, 216 Ill.Dec. at 289.

In Lopez, the plaintiff (an employee of the defendant) was suspected of selling donuts to patrons and pocketing the money she received.

Without explaining his suspicions, plaintiff's manager called plaintiff at home and asked her to come to Winchell's. Plaintiff voluntarily came to

the store and accompanied two managers to a back room. One of the managers put a "latch" on the door and confronted plaintiff with his

suspicions. The court affirmed summary judgment for employer defendant Winchell's stating:

It is essential ... that the confinement be against plaintiff's will and if a person voluntarily consents to the confinement, there can be no false

imprisonment. Moral pressure, as where the plaintiff remains with the defendant to clear himself of suspicion of theft ... is not enough ...

Lopez, 126 Ill.App.3d at 49, 446 N.E.2d at 1312, 81 Ill.Dec. at 510 citing Fort v. Smith, 85 Ill.App.3d 479, 481, 407 N.E.2d 117, 119, 40 Ill.Dec. 886,

888 (5th Dist. 1980)

Voluntary confinement is not as strong a defense when the plaintiff is not an employee. In such situations, courts have found that to hold the

customer/plaintiff could have "unilaterally ended the confrontation ignores the reality of the situation". Robinson v. Weibolts Stores, Inc., 104

Ill.App.3d 1021 (1st Dist 1982).

B. Probable Cause to Effectuate the Arrest.

Existence of probable cause is an absolute bar to claims for false arrest or false imprisonment. Nielsen v. Village of Lake in the Hills, 948 F.Supp.

786 (N.D.Ill. 1996); Kincaid v. Ames Dept. Stores, Inc., 283 Ill.App.3d 555, 561, 670 N.E.2d 1103, 1109, 219 Ill.Dec. 215, 221 (1st Dist. 1996),

reh'd denied, appeal denied, 169 Ill.2d 569, 675 N.E.2d 634, 221 Ill.Dec. 439 (Ill. 1996). Some courts have held that whether the circumstances

amount to probable cause is a question of law to be decided by the court (and not the jury). Serpico v. Menard, Inc., 927 F.Supp. 276 (N.D.Ill.

1996); Ely v. National Super Markets, Inc., 149 Ill.App.3d 752, 756, 500 N.E.2d 120, 124, 102 Ill.Dec. 498, 502 (4th Dist. 1986), appeal denied,

114 Ill.2d 544, 508 N.E.2d 727, 108 Ill.Dec. 416 (Ill. 1987).

Probable cause is defined as "a state of facts ... as would lead a man of ordinary caution and prudence to believe or entertain an honest and

strong suspicion that the person accused is guilty of the offense charged." Carbaugh v. Peat, 40 Ill.App.2d 37, 47, 189 N.E.2d 14, 24 (2d. Dist.

1963). It is not necessary to verify the correctness of each item of information obtained; it is sufficient to act with reasonable prudence and

caution in so proceeding. Turner v. City of Chicago, 91 Ill.App.3d 931, 935, 415 N.E.2d 481, 485, 47 Ill.Dec. 476, 480 (1st Dist. 1980). "It is the

state of mind of the one commencing the [arrest or imprisonment], and not the actual facts of the case or the guilt or innocence of the accused

which is at issue". Serpico v. Menard, Inc., 927 F.Supp. 276, 279 (N.D.Ill. 1996) citing Burghardt v. Remiyac, 207 Ill.App.3d 402, 565 N.E.2d 1049,

152 Ill.Dec. 367, (2d Dist. 1991). Probable cause is determined at the time of subscribing a criminal complaint and it is immaterial that the

accused thereafter may be found not guilty. Ely v. National Super Markets, Inc., 149 Ill.App.3d at 754, 500 N.E.2d at 124, 102 Ill.Dec. at 502.

In Burghardt v. Remiyac, 207 Ill.App.3d. 402, 565 N.E.2d 1049, 152 Ill.Dec. 367, the court affirmed summary judgment in favor of the employer

(office manager of Swanson True Value Hardware Store) who accused plaintiff employee of falsifying refund slips to steal money from the store.

In reviewing whether probable cause existed, the court stated that the "theft complaint against the plaintiff was based upon facts that would

lead a man of ordinary caution and prudence to believe or to entertain an honest and strong suspicion that the plaintiff had committed the

offense of theft." Burghardt, 565 N.E.2d at 1053, 152 Ill.Dec. at 371. Accordingly, the defendant was entitled to summary judgment. In

Burghardt, Defendants systematically reviewed refund receipts which showed that each time plaintiff worked the suspicious receipts were

made. Defendant followed up by questioning one of plaintiff's customers. This revealed the customer never returned any merchandise.

In addition, the Illinois Supreme Court has been very clear to point out that "public policy favors the exposure of crime, and the cooperation of

citizens possessing knowledge thereof is essential to effective implementation of that policy. Persons acting in good faith who have probable

cause to believe crimes have been committed should not be deterred from reporting them by the fear of unfounded suits by those accused.

Joiner v. Benton Community Bank, 82 Ill.2d 40, 42, 411 N.E.2d 229, 231, 44 Ill.Dec. 260, 262 (Ill. 1980).

C. The Illinois Retail Theft Act Provides an Affirmative Defense to Merchants Accused of False Arrest/Imprisonment

The Illinois Retail Theft Act 720 ILCS 5/16(a)-1 et seq. states:

Any merchant who has reasonable grounds to believe that a person has committed retail theft may detain such person, on or off the premises

of a retail mercantile establishment, in a reasonable manner and for a reasonable length of time for all or any of the following purposes:

1. In request identification;

2. To verify such identification;

3. To make reasonable inquiry as to whether such person has in his possession unpurchased merchandise and, to make reasonable

investigation of the ownership of such merchandise;

4. To inform a peace officer of the detention of the person and surrender that person to the custody of a peace officer; ...

720 ILCS 5/16A-5.

Any detention as permitted under the Illinois Retail Theft Act "does not constitute an arrest or an unlawful restraint," and it shall not "render

the merchant liable to the person so detained." 720 ILCS 5/16A-6.

MALICIOUS PROSECUTION

To sustain an action for malicious prosecution, plaintiff has the burden of proving:

1. commencement or continuance of an original criminal or civil judicial proceeding by defendant;

2. termination of proceeding in favor of plaintiff;

3. absence of probable cause for such proceeding;

4. presence of malice;

5. and damages resulting to plaintiff.

Gonzalez v. Chicago Steel Rule Die & Fabricators Co., 106 Ill.App.3d 848, 849, 436 N.E.2d 603, 604, 62 Ill.Dec. 577, 578 (1st Dist. 1982).

DEFENSES

A. Termination Of The Proceedings

Recent Illinois case law has broadened the use of malicious prosecution actions by broadening the definition of "favorable termination." What

constitutes a "favorable termination" is evolving in the Illinois courts. Illinois was formerly in the minority, holding that a favorable termination

required a factual determination of the underlying case, traditionally by trial or by motion for summary judgment. Siegel v. City of Chicago, 127

Ill.App.2d 84, 261 N.E.2d 802 (1970). Accordingly, if a case was voluntarily dismissed, there was no factual ruling and the plaintiff could not

subsequently plead malicious prosecution.

The Illinois Supreme Court has recently reviewed this requirement in two separate cases, one dealing with an underlying criminal case, the

other dealing with an underlying civil case. The Illinois Supreme Court relied heavily on the Restatement (Second) of Torts. In essence, this

element no longer requires an adjudication on the merits. The courts now look at the underlying reason for the termination, irregardless of

whether the termination was based on the merits of the case.

The Illinois Supreme Court also recently reviewed a malicious prosecution case where the underlying case was a criminal charge. Zwick v.

Liautaud, 662 N.E.2d 1238, 215 Ill.Dec. 98 (1996). In Zwick, the underlying criminal charges were nolle prosequi (a nolle prosequi is not a final

disposition of a case but ... is a procedure which reverts the matter to the same condition which existed before the commencement of the

prosecution. People v. Woolsey, 139 Ill.2d 157, 151 Ill.Dec. 309 (1990)). Once again following the Restatement (Second) of Torts, the supreme

court held that "in a civil malicious prosecution context, the majority rule is that a criminal proceeding has been terminated in favor of the

accused when a prosecutor formally abandons the proceeding via a nolle prosequi, unless the abandonment is for reasons not indicative of the

innocence of the accused." Zwick is a case of first impression, and it holds that the "favorable termination" element of a malicious prosecution

case has been broadened beyond an adjudication of the merits. It is important to note that the Supreme Court held the burden of proof of a

favorable termination remained with the plaintiff. Accordingly, just because a matter is nolle prosequi does not mean plaintiff automatically has

proven favorable termination.

The Appellate Courts have had a limited opportunity to explore the parameters of the newly broadened "favorable termination". In one

Appellate Court case which came down only a few months after Zwick v. Liautaud, the First District Appellate Court (Cook County) made a

distinction for criminal cases which were stricken on leave to reinstate (sol). (Traditionally, a criminal case which is sol'd can be reinstated by

the State's Attorney upon proper motion. A case which is Nolle prosequi can not be reinstated.) Relying on case law which pre-dated Zwick v.

Liautaud, the First District held that "a plaintiff whose case is stricken on leave must obtain a final determination in his favor by bringing a

motion for discharge on speedy trial grounds. Failing to do so, the plaintiff failed to meet his burden of proving a favorable final determination."

Vincent v. Williams, 664 N.E.2d 650, 216 Ill.Dec. 13 (1st Dist. 1996). The Fist District court, however, found support from the Supreme Court's

decision of Zwick v. Liautaud, stating that a nolle prosequi charge did not establish that the criminal proceedings were terminated in a manner

consistent with plaintiff's innocence. The Appellate Court did not examine the Illinois Supreme Court's ruling that evidence had to be presented

which established whether or not the discharge of the case was consistent with the plaintiff's innocence.

In a more recent case, Adams v. Sussman and Hertzberg, Ltd., 684 N.E.2d 935, 225 Ill.Dec. 944 (1st Dist 1997), the complaining witness testified

in the malicious prosecution proceedings that his superiors had instructed him not to testify in the criminal action. Because the witness did not

testify, the State's Attorney dismissed the criminal charges. The court in Adams held that "a dismissal on that basis is a termination in favor of

the accused indicative of the accused's innocence." Adams v. Sussman and Hertzberg, Ltd., 225 Ill.Dec. 944, 952. The court in Adams, however,

did affirm the defendant's judgment notwithstanding the verdict on the malicious prosecution claim because the defendant had probable cause

to proceed with the criminal charges.

B. Probable Cause

The existence of probable cause acts as a defense to an action for malicious prosecution. Ely v. National Super Markets, Inc., 149 Ill.App.3d at

754, 500 N.E.2d at 124, 102 Ill.Dec. at 502. The issues involved in asserting probable cause are discussed under false arrest/false imprisonment.

C. Lack of Malice.

In addition, plaintiff must offer at least some evidence of malice, which is an essential element of the claim of malicious prosecution. Ritchey v.

Maksin, 71 Ill.2d 470, 472, 376 N.E.2d 991, 993, 17 Ill.Dec. 662, 664 (Ill. 1978); Robinson v. Econ-O-Corporation, Inc., 62 Ill.App.3d 958, 960, 379

N.E.2d 923, 925, 20 Ill.Dec. 90, 92 (4th Dist. 1978). Malice is defined as initiation of prosecution for any reason other than to bring the party to

justice. Ritchey v. Maksin, 71 Ill.2d 470, 472, 376 N.E.2d 991, 993, 17 Ill.Dec. 662, 664; Salmen v. Kamberos, 206 Ill.App.3d 686, 690, 565 N.E.2d

6, 10, 151 Ill.Dec. 735. 739 (1st Dist. 1990). Malice is not a legal presumption which can be inferred merely from lack of probable cause. Hughes

v. New York Cent. System, 20 Ill.App.2d 224, 227, 155 N.E.2d 809, 812 (1st Dist. 1959). Malice is also not established merely by the fact that

plaintiff was acquitted of the criminal charge. Carbaugh v. Peat, 40 Ill.App.2d 37, 42, 189 N.E.2d 14, 19.

D. Advice of Counsel

Advice of legal counsel is another defense to a claim for malicious prosecution. Karow v. Student Inns, Inc, 43 Ill.App.3d 878, 347 N.E.2d 282, 2

Ill.Dec. 515 (4th Dist. 1976); Accord Wright v. Young, 128 Ill.App.2d 100, 262 N.E.2d 769 (1st Dist. 1970); Galarza v. Sprague, 284 Ill.App. 254; 1

N.E.2d 275 (1st Dist. 1936). In Karow, plaintiff was arrested for criminal trespass even though he was present on the property with the

permission of a lawful tenant. The court held that plaintiff could not have been found guilty of criminal trespass as a matter of law. However,

the court affirmed judgment on behalf of the defendants in part based on the affirmative defense of legal advice. In Karow, the defendant had

made a full disclosure of the plaintiff's activities to the State's Attorney and accordingly, could not have been found liable. In general, this

affirmative defense is viable if the defendant can show it relied on an attorney's advice after making a full, truthful and correct disclosure.

CONCLUSION

Not every criminal charge will lead to a finding of guilty. Some will be dismissed when a primary witness can not be located or when evidence is

lost. Some will be defeated at trial because the necessary elements are not established. (For example - when it is not shown that the

perpetrator passed the last possible place to pay for the merchandise).

But, as evidenced by the defenses outlined above, the best response to a claim of false arrest and/or malicious prosecution is a solidly

supported criminal charge. Documentation of the observations, written down immediately after the occurrence, and videotape of the arrest,

when possible, are critical to establishing probable cause. All witnesses to the occurrence, or even the events leading up to the theft, are

important to defend the civil litigation.

With the facts in place and the defenses offered by Illinois law, a motion for summary judgment is often a viable, and successful, strategy.

Invasion of privacy is a relatively new tort in American law, having appeared on the scene in the late 1800s. According to the Restatement

(Second) of Torts, an individual's right to privacy, and a corresponding right to personal injury compensation for the invasion of that right, has

now come to be recognized in virtually all U.S. jurisdictions.

What one considers the tort of invasion of privacy is actually four separate and distinct causes of action. Each of the invasion of privacy torts

involves the intrusion into a person's private activities in such a manner as to embarrass, humiliate or outrage a person of ordinary sensibilities.

Intentional Intrusion Invasion of Privacy

Intrusion is a form of invasion of privacy that involves the intentional and unauthorized intrusion, physically or otherwise, into someone's

solitude or private activities. In order to be actionable, the intrusion must be of a type that would be highly offensive to the ordinary reasonable

person. Examples of intrusion may include such things as eavesdropping, reading someone's e-mail, wire tapping someone's telephone, or

searching through someone's private possessions.

Appropriating Someone's Publicity Rights to Their Name or Likeness

The tort of appropriation is a form of invasion of privacy that invades someone's right of publicity. Appropriation consists of the unauthorized

use of someone's name, personality or photograph for the defendant's benefit. In other words, this tort involves appropriating some element

of the plaintiff's personality for commercial use without the plaintiff's permission. An example would be the unauthorized use of a famous

basketball player's photograph on an advertisement for sporting goods.

Public Disclosure of Private Facts

The public disclosure of private facts is an actionable invasion of privacy if it would be highly offensive to the ordinary person to have those

facts publicized, and if the facts are not legitimately matters of public concern. This tort amounts to unreasonable publicity about the plaintiff,

but it must involve facts that are not already part of the public record. It is not a defense that the facts about the plaintiff are true, so long as

the other criteria are met.

Publicity Placing Someone in a False Light

False light invasion of privacy involves publicizing something about the plaintiff that places the plaintiff in a false and objectionable position in

the public eye. The law does not require that the publicized information be private, but it does require that it be false or be given a false

connotation. This tort may involve attributing to the plaintiff characteristics, conduct or beliefs that are false. Similar to defamation, false light

invasion of privacy exposes the plaintiff to ridicule, hatred or contempt.

Not all U.S. jurisdictions recognize all the invasion of privacy torts. Those that do recognize these torts may have differing approaches to each

tort. Moreover, most states impose time limits on bringing tort lawsuits. A person who believes he or she is entitled to personal injury

compensation for invasion of privacy should contact a local attorney for advice and counsel.

Sources: Restatement (Second) of Torts, 652 (1965); S.B. v. St. James School, 959 So. 2d 72 (Ala. 2006).

Additional Resource: How to Hire an Attorney

Disclaimer: This article is in no way intended as legal advice. For help with specific legal issues, one should contact a licensed attorney in one's

own jurisdiction.

A conversion is the unauthorized assumption of the right of ownership over the personal property of another to the exclusion of the owners

rights[i].

The tort of conversion is an intentional exercise of dominion and control over a chattel which so seriously interferes with the right of another to

control it that the actor may justly be required to pay the other the full value of the chattel[ii].

Thus, conversion is the deprivation of anothers right of property in or use or possession of a chattel or other interference therewith without

the owners consent and without lawful justification[iii].

The elements of conversion are[iv]:

the plaintiffs ownership or right to possession of the property;

the defendants conversion by wrongful act inconsistent with the property rights of the plaintiff; and

damages.

A conversion may be committed by unreasonably withholding possession from one who has the right to it.

A person not in lawful possession of a chattel may commit conversion by [v]:

intentionally dispossessing the lawful possessor of the chattel,

intentionally using a chattel in his possession without authority so to use it,

receiving a chattel pursuant to an unauthorized sale with intent to acquire for himself or for another a proprietary interest in it,

disposing of a chattel by an unauthorized sale with intent to transfer a proprietary interest in it, or

refusing to surrender a chattel on demand to a person entitled to lawful possession.

A conversion may be proved in one of three ways:

by tortious taking;

by any use or appropriation to the use of the person in possession, indicating a claim of right in opposition to rights of the owner; or

refusal to give up possession to the owner on demand[vi].

A conversion is an intentional tort[vii]. The element of intent that must be proven is the intent to exercise dominion and control over the

plaintiffs property in a manner inconsistent with the plaintiffs rights[viii]. The intent required is not necessarily a matter of conscious

wrongdoing.

However, the intent or purpose to do a wrong is not a necessary element to establish conversion[ix]. In Chem-Age Indus. v. Glover, 2002 SD

122 (S.D. 2002), the court held that the foundation for the action of conversion rests neither in the knowledge nor the intent of the defendant.

It rests upon the unwarranted interference by a defendant with the dominion over the property of the plaintiff from which injury to the latter

results.

Since the act must be knowingly done, neither negligence active or passive nor a breach of contract even though it result in injury to or loss of

specific property, constitutes a conversion[x]. It follows therefore that mistake, good faith, and due care are ordinarily immaterial and cannot

be set up as defenses in an action for conversion.

A person is not relieved of liability to another for trespass to a chattel or for conversion by his/her belief because of a mistake of law or fact not

induced by the other that s/he:

has possession of the chattel or is entitled to its immediate possession;

has the consent of the other or of one with power to consent for him or her; or

is otherwise privileged to act.

The essence of a conversion is not the acquisition of property, but the wrongful deprivation of that property from its true owner[xi]. One who

is lawfully in possession of property may nevertheless be liable for a conversion for exceeding the scope of authority for that lawful possession

when the use seriously violates the true owners right of control.

To establish a conversion claim, a plaintiff must prove that:

it had a possessory interest in the property,

the defendants intentionally interfered with the plaintiffs possession, and

the defendants acts are the legal cause of the plaintiffs loss of property.

At common law, even unwitting acts by the trespasser are sufficient to sustain a cause of action for conversion. A creditors improper

treatment of collateral can amount to a conversion[xii]. A creditor who converts collateral is entitled to a credit against the debtors recovery

for the debt secured by the collateral. The tort of conversion generally may extend to the type of intangible property rights that are merged or

incorporated into a transferable document.

A possessory interest in personal property is sufficient to maintain an action for conversion against one who sells that property without

notifying the lawful possessor. Even though the lawful possessors do not have legal title, if s/he exercises control of it by taking possession of it

and maintaining it for a period of time, his or her rights in the chattel are sufficient.

The gravamen of an action for conversion lies in the defendants taking the plaintiffs personalty without consent and exercising dominion over

it inconsistent with the plaintiffs right to possession[xiii]. The focus of inquiry is whether a defendant has appropriated to his/her own use the

chattel of another without the latters permission and without legal right.

In order to sustain an action for conversion of personal chattels, a plaintiff must demonstrate an ownership or possessory interest in the

property at the time of the conversion[xiv].

A plaintiff must also identify the allegedly converted property with reasonable certainty, in order to render it capable of identification, for the

purpose of determining whether the property in fact belonged to the plaintiff at the time of its conversion.

One jurisdiction states that a conversion is a continuing tort, lasting as long as the person entitled to the use and possession of property is

deprived of it. It does not necessarily end when the original wrongdoer transfers physical possession to another.

However, another jurisdiction states that conversion is not a continuing tort and damages for a conversion are based upon the propertys fair

market value at the time and place of the conversion, plus interest on it.

Further, another jurisdiction has held that a wrongful conversion cause of action must be filed before the statute of limitations runs out and the

continuing tort theory does not apply.

A plaintiff who proved conversion in a common law action is entitled to damages equal to the full value of the chattel at the time and place of

conversion[xv]. The measure of damages in conversion is the fair market value of the property at the time and place of the conversion[xvi].

When the defendant satisfies the judgment in the action for conversion, title to the chattel passes to him so that he is in effect required to buy

it at a forced judicial sale.

The modern tort of conversion subjects the wrongdoer to liability to the possessor for the entire value of the chattel in addition to any special

damages resulting from the conversion and this liability does not depend on the existence of the possessors responsibility to the owner for the

loss of the chattel[xvii].

Although the normal measure of damages for conversion is the value of the property at the time of the conversion and a fair compensation for

the time and money properly expended in pursuit of the property, emotional distress damages are also allowed[xviii].

[i] Litzinger v. Estate of Litzinger (In re Litzinger), 340 B.R. 897 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2006)

[ii] Carver v. Quality Inspection & Testing, 946 P.2d 450 (Alaska 1997)

[iii] Stevenson v. Economy Bank of Ambridge, 413 Pa. 442 (Pa. 1964)

[iv] Kasdan, Simonds, McIntyre, Epstein & Martin v. World Sav. & Loan Assn (In re Emery), 317 F.3d 1064 (9th Cir. Cal. 2003)

[v] Baram v. Farugia, 606 F.2d 42 (3d Cir. Pa. 1979)

[vi] Litzinger v. Estate of Litzinger (In re Litzinger), 340 B.R. 897 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2006)

[vii] Vaughn v. Vaughn, 146 Md. App. 264 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 2002)

[viii] Id

[ix] Chem-Age Indus. v. Glover, 2002 SD 122 (S.D. 2002)

[x] Taylor v. Forte Hotels Intl, 235 Cal. App. 3d 1119 (Cal. App. 4th Dist. 1991)

[xi] Yaeger v. Magna Corp. (In re Magna Corp.), 2005 Bankr. LEXIS 1114 (Bankr. M.D.N.C. Mar. 14, 2005)

[xii] Chemical Sales Co. v. Diamond Chemical Co., 766 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. Mo. 1985)

[xiii] DeChristofaro v. Machala, 685 A.2d 258 (R.I. 1996)

[xiv] Id

[xv] Baram v. Farugia, 606 F.2d 42 (3d Cir. Pa. 1979)

[xvi] Vaughn v. Vaughn, 146 Md. App. 264 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 2002)

[xvii] Wallander v. Barnes, 341 Md. 553 (Md. 1996)

[xviii] Spates v. Dameron Hospital Assn., 114 Cal. App. 4th 208 (Cal. App. 3d Dist. 2003)

Elements of Conversion

Conversion is a tort that exposes you to liability for damages in a civil lawsuit. It applies when someone intentionally interferes with personal

property belonging to another person. To make out a conversion claim, a plaintiff must establish four elements:

First, that the plaintiff owns or has the right to possess the personal property in question at the time of the interference;

Second, that the defendant intentionally interfered with the plaintiff's personal property (sometimes also described as exercising

"dominion and control" over it);

Third, that the interference deprived the plaintiff of possession or use of the personal property in question; and

Fourth, that the interference caused damages to the plaintiff.

The most direct and obvious way to commit conversion is by taking personal property that belongs to someone else without permission. For

example, if you take a framed photograph from the wall of a local restaurant or a document from someone's desk, you may be held liable for

conversion, assuming you retain the property for a substantial period of time and thereby interfere with the rightful owner's use and

possession of it. It does not matter whether you intend to publish the information, photos, or other content.

However, if you remove paperwork or photographs from someone's office or home temporarily in order to copy the information -- intending to

return the documents to the owner -- you might not be liable for conversion because this temporary interference does not necessarily deprive

the rightful owner of the possession or use of the property. See Harper & Row Pubs. v. Nation Enters., 723 F.2d 195, 201 (2nd Cir. 1983)

("Conversion requires not merely temporary interference with property rights, but the exercise of unauthorized dominion and control to the

complete exclusion of the rightful possessor."). You should be aware that taking property from someone can also expose you to criminal liability

under state laws.

You can also commit conversion by receiving and retaining property from someone who does not have the right to give the property away. This

issue could come up when you receive documents from sources. For example, if a bank employee gives you checking account records for bank

customers, you may both be liable for conversion because the employee likely does not have permission from his or her employer to turn over

a customer's records. But the legal analysis is not that simple, and whether or not you could be held liable for conversion under these

circumstances depends on whether the records you receive are originals or copies.

As a rule of thumb, you can generally receive and retain copies of documents that belong to someone else, but you may not receive and retain

the originals of such documents. The reason is that "the possession of copies of documents -- as opposed to the documents themselves -- does

not amount to an interference with the owner's property sufficient to constitute conversion."FMC Corp. v. Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 915 F.2d

300, 303 (7th Cir. 1990). However, you may be held liable for conversion for receiving and retaining copies if the rightful owner no longer has

either originals or copies of the documents in question. Even if you are held liable for conversion and must return the documents in question,

you generally are entitled under the First Amendment to retain copies of the documents for yourself and to disseminate any information

contained in them. See id. at 304-05.

California has long recognized the right to recover damages for the intentional and unreasonable infliction of mental or emotional

distress which results in foreseeable physical injury to plaintiff. California courts have also acknowledged the right to recover damages for

emotional distress alone, without consequent physical injuries, in cases involving extreme and outrageous intentional invasions of one's mental

and emotional tranquility. (State Rubbish etc. Assn. v. Siliznoff (1952) 38 Cal.2d 330, 336-337)

INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS

The elements of a prima facie case for the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress are:

(1) outrageous conduct by the defendant;

(2) the defendant's intention of causing or reckless disregard of the probability of causing emotional distress;

(3) the plaintiff's suffering severe or extreme emotional distress; and

(4) actual and proximate causation of the emotional distress by the defendant's outrageous conduct. (Alcorn v. Anbro Engineering, Inc (1970) 2

Cal.3d 493, 497-498

EMOTIONAL DISTRESS-DEFINED

The term "emotional distress" means mental distress, mental suffering or mental anguish. It includes all highly unpleasant mental reactions,

such as fright, nervousness, grief, anxiety, worry, mortification, shock, humiliation and indignity, as well as physical pain.

SEVERE-DEFINED

The word "severe," in the phrase "severe emotional distress," means substantial or enduring as distinguished from trivial or transitory. Severe

emotional distress is emotional distress of such substantial quantity or enduring quality that no reasonable person in a civilized society should

be expected to endure it. In determining the severity of emotional distress consideration is given to its intensity and duration.

The Restatement view is that liability "does not extend to mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions, or other trivialities,"

but only to conduct so extreme and outrageous "as to go beyond all possible bonds of decency, and to be regarded as atrocious, and utterly

intolerable in a civilized community." (Rest. 2d Torts, 46, com. d; see Prosser, Law of Torts, supra, at pp. 46-47.) "The emotional distress must

in fact exist, and it must be severe." (Prosser, Law of Torts, supra, p. 51; Rest.2d Torts, supra, 46, Com. j.)

EXTREME AND OUTRAGEOUS CONDUCT-DEFINED

Extreme and outrageous conduct is conduct which goes beyond all possible bounds of decency so as to be regarded as atrocious and utterly

intolerable in a civilized community.

Extreme and outrageous conduct is not mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions or other trivialities. All persons must

necessarily be expected and required to be hardened to a certain amount of rough language and to occasional acts that are definitely

inconsiderate and unkind.

Extreme and outrageous conduct, however, is conduct which would cause an average member of the community to immediately react in

outrage.

EFFECT OF RELATIONSHIP OF PARTIES

The extreme and outrageous character of the conduct of a defendant may arise from an abuse of a position, or relationship to a plaintiff, which

gives such a defendant actual or apparent authority over a plaintiff, or power to affect a plaintiff's interests.

SUSCEPTIBILITY OF PLAINTIFF

The extreme and outrageous character of a defendant's conduct may arise from defendant's knowledge that a plaintiff is peculiarly susceptible

to emotional distress by reason of some physical or mental condition or peculiarity. Conduct may become extreme and outrageous when a

defendant proceeds in the face of such knowledge, where it would not be so if defendant did not know.

INTENTIONAL AND RECKLESS -- DEFINED

A defendant intended to inflict emotional distress if it is established that he or she desired to cause such distress or knew that such distress was

substantially certain to result from his or her conduct.

A defendant's conduct is in reckless disregard of the probability of causing emotional distress if he or she has knowledge of a high degree of

probability that emotional distress will result and acts with deliberate disregard of that probability or with a conscious disregard of the probable

results.

PRIVILEGE

Conduct, which under other conditions would be extreme and outrageous, may be privileged and a defendant is not liable:

When a defendant has done no more than to insist upon his or her legal rights in a permissible way, even though he or she is well aware that

such insistence is certain to cause emotional distress. If you find that defendant in good faith believed that he or she was acting under a legal

right, he or she shall be considered as having been acting under such right even though, in fact, he or she had no such right.

When a defendant makes statements in the course of an official proceeding.

NEGLIGENT INFLICTION OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS

The elements of a claim of negligent infliction of emotional distress are:

1. The defendant engaged in negligent conduct or a willful violation of a statutory standard;

2. The plaintiff suffered serious emotional distress;

3. The defendant's negligent conduct or willful violation of statutory standards was a cause of the serious emotional distress.

Serious emotional distress is an emotional reaction which is not an abnormal response to the circumstances. It is found where a reasonable

person would be unable to cope with the mental distress caused by the circumstances.

CAUSES OF NERVOUS SHOCK

A shock to the nervous system may be caused either by some physical impact or by fright caused by exposure to imminent peril.

BYSTANDER RECOVERY OF EMOTIONAL DISTRESS

Bystanders may recover for emotional distress damage only under very limited circumstances. The emotional disturbance suffered must be

"serious and verifiable," and must be tied as a matter of proximate causation to the observation of the serious injury or death of an immediate

family member. Finally, the plaintiff himself must have been in the "zone of danger" i.e, must have been exposed to a risk of bodily harm by the

conduct of the defendant.

The essential elements of a claim of wrongful infliction of emotional distress upon a bystander are:

1. The defendant was negligent; or the defendant manufactured or supplied a defective product;

2. Defendant's negligence or defective product was a cause of injury or death to the victim;

3. Plaintiff was the spouse, parent, or child, of the victim;

4. Plaintiff was present at the scene of the injury-producing event or accident at the time it occurred;

5. Plaintiff was then aware that such event or accident caused the injury to the victim;

6. As a result, plaintiff suffered serious emotional distress.

Serious emotional distress is an emotional reaction beyond that which would be anticipated in a witness not related to the injured person and

which is not an abnormal response to the circumstances. It is found when a reasonable person would be unable to cope with the mental

distress caused by the circumstances of the accident and injury to the near relative.

You might also like

- Bards RecommendationsDocument135 pagesBards RecommendationsthewizardsofcontentNo ratings yet

- Torts and Strict LiabilityDocument46 pagesTorts and Strict LiabilityRaiyan AzimNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property Law: Laws Control Businesses Formed ManagedDocument19 pagesIntellectual Property Law: Laws Control Businesses Formed ManagedNadia BurchardtNo ratings yet

- Personal Injury Lawsuits & SettlementsFrom EverandPersonal Injury Lawsuits & SettlementsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Data DiddlingDocument6 pagesData DiddlingTaher RangwalaNo ratings yet

- Writ of ConspiracyDocument4 pagesWrit of Conspiracysaoudtaha60No ratings yet

- Torts and Cyber Torts Chapter 5Document7 pagesTorts and Cyber Torts Chapter 5Tino AlappatNo ratings yet

- Wilfully NegligenceDocument7 pagesWilfully NegligenceEditha RoxasNo ratings yet

- Torts TopicsDocument8 pagesTorts TopicsMazhar Ali BalochNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Criminal Defenses and Their Role in Criminal ProceedingsFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Criminal Defenses and Their Role in Criminal ProceedingsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Finals Reading 1Document12 pagesFinals Reading 1rina apostolNo ratings yet

- Who in Identity Theft Needs A LawyerDocument8 pagesWho in Identity Theft Needs A LawyerRizky Amalia PutriNo ratings yet

- Fraud in InsuranceDocument54 pagesFraud in Insurance9220501752No ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Torts and Insurance LawDocument17 pagesUnit 3 - Torts and Insurance LawmmNo ratings yet

- Fatal Accident Claims PresentationDocument19 pagesFatal Accident Claims PresentationaNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Glossary of Legal Terms, Law Essentials: Essential Legal Terms Defined and AnnotatedFrom EverandComprehensive Glossary of Legal Terms, Law Essentials: Essential Legal Terms Defined and AnnotatedNo ratings yet

- Love Thy Neighbor, Barangay Legal Aid Free Information GuideFrom EverandLove Thy Neighbor, Barangay Legal Aid Free Information GuideNo ratings yet

- Victim Impact Statement InfoDocument2 pagesVictim Impact Statement InfoWendy Warren VilleneuveNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Civil and CriminalDocument3 pagesDifference Between Civil and CriminalShubham Saurabh100% (1)

- Frauds and ScamsDocument100 pagesFrauds and ScamsSunil Rawat100% (1)

- What Is Tort Law?: Key TakeawaysDocument11 pagesWhat Is Tort Law?: Key TakeawaysTouhid SarrowarNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Civil Law and Criminal LawDocument5 pagesDifferences Between Civil Law and Criminal LawAmita SinwarNo ratings yet

- Victim Restitution For Financial and Emotional Suffering From FraudDocument25 pagesVictim Restitution For Financial and Emotional Suffering From FraudCharlton Butler100% (1)

- Witnesses Who LieDocument4 pagesWitnesses Who LieTaskmasters Canada100% (1)

- RestitutionDocument5 pagesRestitutionKomalNo ratings yet

- NegligenceDocument24 pagesNegligenceJosh LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts ExplainedDocument28 pagesLaw of Torts ExplainedSam KariukiNo ratings yet

- Victim Impact StatementDocument3 pagesVictim Impact StatementCheemTalzNo ratings yet

- ContentsDocument46 pagesContentsTilak SalianNo ratings yet

- Damages: Atty. Misheena Joyce C. Tiatco 14 February 2020Document20 pagesDamages: Atty. Misheena Joyce C. Tiatco 14 February 2020MJ CarreonNo ratings yet

- Dirty Little Secrets of Personal Injury Claims: What Insurance Companies Don't Want You to Know; and What Attorneys Won't Tell You, About Handling Your Own ClaimFrom EverandDirty Little Secrets of Personal Injury Claims: What Insurance Companies Don't Want You to Know; and What Attorneys Won't Tell You, About Handling Your Own ClaimNo ratings yet

- Tort of Negligence (Studypol, Pineda)Document3 pagesTort of Negligence (Studypol, Pineda)Kassandra Mae PinedaNo ratings yet

- The Law of Torts - IntroductionDocument5 pagesThe Law of Torts - IntroductionRohanNo ratings yet

- Group TWO Members NegligenceDocument26 pagesGroup TWO Members NegligenceAllan SsemujjuNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts in KenyaDocument42 pagesLaw of Torts in KenyaDickson Tk Chuma Jr.100% (1)

- B2000632 (Chanic Suining)Document6 pagesB2000632 (Chanic Suining)ChanicSuiningNo ratings yet

- Loan Modifications, Foreclosures and Saving Your Home: With an Affordable Loan Modification AgreementFrom EverandLoan Modifications, Foreclosures and Saving Your Home: With an Affordable Loan Modification AgreementNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort: Liability For Damages That Arise From Breach of A Legal DutyDocument13 pagesLaw of Tort: Liability For Damages That Arise From Breach of A Legal DutyimtiazbulbulNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 Torts LawDocument17 pagesLecture 3 Torts LawHasnain HaiderNo ratings yet

- I Need You To LoseDocument22 pagesI Need You To LoseBrandon FerrickNo ratings yet

- Unidad Derecho DañosDocument12 pagesUnidad Derecho DañosmilagrosNo ratings yet

- What Is Fraud On The CourtDocument5 pagesWhat Is Fraud On The CourtJohnnyLarsonNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts and The Construction IndustryDocument48 pagesLaw of Torts and The Construction IndustryIdowuNo ratings yet

- Torts Damages Flow ChartDocument3 pagesTorts Damages Flow Chartmkelly2109100% (2)

- Avoidance of Fees Another Advantage of Structured SettlementsDocument1 pageAvoidance of Fees Another Advantage of Structured SettlementsBob NigolNo ratings yet

- How To Properly Handle Criminal Offences - Melbourne Cirminal LawyersDocument12 pagesHow To Properly Handle Criminal Offences - Melbourne Cirminal LawyersFiona ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Affirmative Defenses - Defenses To Use in Debt LawsuitsDocument3 pagesAffirmative Defenses - Defenses To Use in Debt LawsuitsWarriorpoetNo ratings yet

- TORT LAWDocument14 pagesTORT LAWvelinagrNo ratings yet

- Asset Protection for the Rest of Us: A Layman's Guide to Asset Protection PlanningFrom EverandAsset Protection for the Rest of Us: A Layman's Guide to Asset Protection PlanningRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Good Samaritan law protects emergency aid providersDocument9 pagesGood Samaritan law protects emergency aid providersma_tabora6283No ratings yet

- Tort LawDocument2 pagesTort Law9wvzxxpb5nNo ratings yet

- Insurance Fraud: What is it and Types ExplainedDocument19 pagesInsurance Fraud: What is it and Types ExplainedDaniela DcNo ratings yet

- Capacity of Parties: Chapter - 04Document25 pagesCapacity of Parties: Chapter - 04Okasha AliNo ratings yet

- Intentional ListDocument5 pagesIntentional ListLindaGuan100% (1)

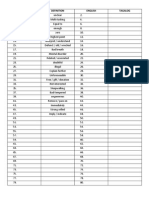

- SpellingDocument5 pagesSpellingannesd29No ratings yet

- VocabulariesDocument4 pagesVocabulariesannesd29No ratings yet

- Base Form Past Present FutureDocument1 pageBase Form Past Present Futureannesd29No ratings yet

- Singular and PluralDocument1 pageSingular and PluralLindaGuanNo ratings yet

- Simple: Positive Comparative SuperlativeDocument1 pageSimple: Positive Comparative Superlativeannesd29No ratings yet

- Verb conjugations: base, past, present formsDocument1 pageVerb conjugations: base, past, present formsannesd29No ratings yet

- Crim Board ExamDocument7 pagesCrim Board Examannesd29100% (1)

- English ExerciseDocument1 pageEnglish Exerciseannesd29No ratings yet

- Singular Plural Singular PluralDocument3 pagesSingular Plural Singular Pluralannesd29No ratings yet

- Crim Digested CasesDocument81 pagesCrim Digested Casesannesd29No ratings yet

- Singular and PluralDocument1 pageSingular and PluralLindaGuanNo ratings yet

- Simple: Positive Comparative SuperlativeDocument1 pageSimple: Positive Comparative Superlativeannesd29No ratings yet

- List of Verb TensesDocument9 pagesList of Verb Tensesannesd29No ratings yet

- Special Torts OutlineDocument5 pagesSpecial Torts Outlineannesd29No ratings yet

- English Vocabulary With DefinitionDocument1 pageEnglish Vocabulary With Definitionannesd29No ratings yet

- Philippine Constitution and GovernmentDocument90 pagesPhilippine Constitution and Governmentannesd29No ratings yet

- Engaging The Powers Discernment and Resistance in A World of Domination by Walter Wink - MagnificentDocument3 pagesEngaging The Powers Discernment and Resistance in A World of Domination by Walter Wink - MagnificentMiroslavNo ratings yet

- Dubai Aviation Exhibition and Sponsorship 2019Document4 pagesDubai Aviation Exhibition and Sponsorship 2019Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Bellefonte Walkout Letter To ParentsDocument1 pageBellefonte Walkout Letter To ParentsMatt StevensNo ratings yet

- English Act 3 Scene 2Document3 pagesEnglish Act 3 Scene 2Anonymous QN2QVwNNo ratings yet

- 3.15, 4.15 Taking and Leaving Phone MessageDocument4 pages3.15, 4.15 Taking and Leaving Phone MessageRinto Bagus pNo ratings yet

- Citizenship Law IntroductionDocument10 pagesCitizenship Law Introductionanusid45No ratings yet

- The Clash - A Brief HistoryDocument11 pagesThe Clash - A Brief HistoryDan AlexandruNo ratings yet

- CAPITOL SUBDIVISIONS, INC. v. PROVINCE OF NEGROS OCCIDENTAL G.R. No. L-16257, January 31, 1963, 7 SCRA 60Document2 pagesCAPITOL SUBDIVISIONS, INC. v. PROVINCE OF NEGROS OCCIDENTAL G.R. No. L-16257, January 31, 1963, 7 SCRA 60ben carlo ramos srNo ratings yet

- Solidary Liability of Principals: ExamplesDocument6 pagesSolidary Liability of Principals: Examplessui_generis_buddyNo ratings yet

- Ir Unit 2Document26 pagesIr Unit 2Richa SharmaNo ratings yet

- Maltese History NotesDocument18 pagesMaltese History NotesElise Dalli100% (2)

- Citizen's Surety v. Melencio HerreraDocument1 pageCitizen's Surety v. Melencio HerreraVanya Klarika NuqueNo ratings yet

- Angat vs. RepublicDocument6 pagesAngat vs. RepublicternoternaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document69 pagesAssignment 3Era Yvonne KillipNo ratings yet

- Manning Prosecution ExhibitsDocument1,460 pagesManning Prosecution ExhibitsLeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Sister Brother Incest Data From Anonymous Computer Assisted Self InterviewsDocument39 pagesSister Brother Incest Data From Anonymous Computer Assisted Self InterviewsianjdrojasgNo ratings yet

- Prosperity Gospel and The Catholic Errol FernandesDocument3 pagesProsperity Gospel and The Catholic Errol FernandesFrancis LoboNo ratings yet

- Zulm Hindi MovieDocument21 pagesZulm Hindi MovieJagadish PrasadNo ratings yet

- Drug Abuse - Effects and Solutions (Informal Letter)Document6 pagesDrug Abuse - Effects and Solutions (Informal Letter)Qing Yi0% (1)

- Michael Rubens BloombergDocument3 pagesMichael Rubens BloombergMarina Selezneva100% (1)

- Makati City charter provisions challengedDocument2 pagesMakati City charter provisions challengedJovelan V. EscañoNo ratings yet

- Lee Tek Sheng Vs CA Case DigestDocument2 pagesLee Tek Sheng Vs CA Case DigestXuagramellebasiNo ratings yet

- Aion Gladiator GuideDocument173 pagesAion Gladiator GuideSamuel Torrealba50% (2)

- 5.implantasi & PlasentasiDocument111 pages5.implantasi & PlasentasiherdhikaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Correction of Transcript of Stenographic NotesDocument5 pagesMotion For Correction of Transcript of Stenographic Notesmisyeldv0% (1)

- Difference Between Cheque and Bill of Exchange: MeaningDocument6 pagesDifference Between Cheque and Bill of Exchange: MeaningDeeptangshu KarNo ratings yet

- COMS241 Example 1Document3 pagesCOMS241 Example 1Ujjaval PatilNo ratings yet

- Quotes For PageDocument161 pagesQuotes For PageSteve DurchinNo ratings yet

- An Impasse in SAARC - ORFDocument4 pagesAn Impasse in SAARC - ORFTufel NooraniNo ratings yet

- Contract Between Advertising Agency and Individual ArtistDocument11 pagesContract Between Advertising Agency and Individual ArtistDOLE Region 6No ratings yet