Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sigan Vs Villanueva

Uploaded by

wesleybooks0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

171 views2 pagescase digest

Original Title

Sigan vs Villanueva

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentcase digest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

171 views2 pagesSigan Vs Villanueva

Uploaded by

wesleybookscase digest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Sig-an vs Villanueva

G.R. No. 173227 January 20, 2009

SEBASTIAN SIGA-AN, Petitioner, vs. ALICIA VILLANUEVA, Respondent.

FACTS:

Villanueva was a businesswoman engaged in supplying office materials and equipment to PNO (Phil Navy

Office), while petitioner was a military officer and comptroller. Villanueva claims that in 1992, Siga-an

approached her inside the PNO and offered to loan her the amount of 540k, which she accepted. The loan

agreement was not reduced in writing, nor was there any stipulation as to interest.

In Aug 1993, Villanueva issued a check worth 500k to Siga-an as partial payment. In Oct 1993, she issued

another check for 200k as payment of the remaining balance. Siga-an told her that since she paid a total

amount of 700k for the 540k loan, the excess amount of 160k would be applied as interest. Not satisfied with

the excess amount as interest, Siga-an pestered Villanueva for additional interest. Siga-an threatened to block

Villanuevas transactions with PNO if she would not comply with his demand. Villanueva was thus forced to

pay additional amounts as interest for the loan (amounting to 1.2M for both the loan and interest paid).

Thereafter, respondent consulted a lawyer and was told that petitioner could not validly collect interest since

there was no agreement regarding the payment of interest. Respondent sent a demand letter to petitioner,

asking for the return of the excess amount of 660k, which was ignored by the petitioner. Respondent

subsequently filed a complaint for sum of money before the RTC.

RTC held that respondent made an overpayment of her loan obligation and that the petitioner should refund

the excess amount pursuant to the principle of solutio indebiti (RTC ruled that interests due should not be

included since there was no agreement regarding interest). CA affirmed.

ISSUE: W/N respondent is liable for interest NO

HELD:

Interest is a compensation fixed by the parties for the use or forbearance of money. Article 1956 of the Civil

Code, which refers to monetary interest, specifically mandates that no interest shall be due unless it has been

expressly stipulated in writing. As can be gleaned from the foregoing provision, payment of monetary interest

is allowed only if: (1) there was an express stipulation for the payment of interest; and (2) the agreement for

the payment of interest was reduced in writing. The concurrence of the two conditions is required for the

payment of monetary interest. Thus, we have held that collection of interest without any stipulation therefor

in writing is prohibited by law.

It appears that petitioner and respondent did not agree on the payment of interest for the loan. We have

carefully examined the RTC Decision and found that the RTC did not make a ruling therein that petitioner and

respondent agreed on the payment of interest at the rate of 7% for the loan. The RTC clearly stated that

although petitioner and respondent entered into a valid oral contract of loan amounting to P540,000.00, they,

nonetheless, never intended the payment of interest thereon.

There are instances in which an interest may be imposed even in the absence of express stipulation, verbal or

written, regarding payment of interest. Article 2209 of the Civil Code states that if the obligation consists in the

payment of a sum of money, and the debtor incurs delay, a legal interest of 12% per annum may be imposed

as indemnity for damages if no stipulation on the payment of interest was agreed upon. Likewise, Article 2212

of the Civil Code provides that interest due shall earn legal interest from the time it is judicially demanded,

although the obligation may be silent on this point.

All the same, the interest under these two instances may be imposed only as a penalty or damages for breach

of contractual obligations. It cannot be charged as a compensation for the use or forbearance of money. In

other words, the two instances apply only to compensatory interest and not to monetary interest. The case at

bar involves petitioners claim for monetary interest.

Issue on solutio indebiti

Under Article 1960 of the Civil Code, if the borrower of loan pays interest when there has been no stipulation

therefor, the provisions of the Civil Code concerning solutio indebiti shall be applied. Article 2154 of the Civil

Code explains the principle of solutio indebiti. Said provision provides that if something is received when there

is no right to demand it, and it was unduly delivered through mistake, the obligation to return it arises. In such

a case, a creditor-debtor relationship is created under a quasi-contract whereby the payor becomes the

creditor who then has the right to demand the return of payment made by mistake, and the person who has

no right to receive such payment becomes obligated to return the same. The quasi-contract of solutio indebiti

harks back to the ancient principle that no one shall enrich himself unjustly at the expense of another.31 The

principle of solutio indebiti applies where (1) a payment is made when there exists no binding relation

between the payor, who has no duty to pay, and the person who received the payment; and (2) the payment is

made through mistake, and not through liberality or some other cause.32 We have held that the principle of

solutio indebiti applies in case of erroneous payment of undue interest.33

It was duly established that respondent paid interest to petitioner. Respondent was under no duty to make

such payment because there was no express stipulation in writing to that effect. There was no binding relation

between petitioner and respondent as regards the payment of interest. The payment was clearly a mistake.

Since petitioner received something when there was no right to demand it, he has an obligation to return it.

You might also like

- Digest Credit Trans CasesDocument7 pagesDigest Credit Trans CasesGracelyn Enriquez Bellingan100% (1)

- Siga-An v. VillanuevaDocument2 pagesSiga-An v. VillanuevaAbbyElbambo100% (1)

- Silos vs. PNBDocument2 pagesSilos vs. PNBAnathea CadagatNo ratings yet

- Case Digest For Credit TransactionsDocument13 pagesCase Digest For Credit TransactionsEqui TinNo ratings yet

- Sales DigestDocument5 pagesSales DigestJohansen FerrerNo ratings yet

- Timber Company Judgment Paid in FullDocument2 pagesTimber Company Judgment Paid in FullCeline GarciaNo ratings yet

- Victorias Milling Co. Inc. v. CADocument20 pagesVictorias Milling Co. Inc. v. CADexter CircaNo ratings yet

- Crimpro Case v1Document68 pagesCrimpro Case v1roxiel chuaNo ratings yet

- CREDIT DigestDocument14 pagesCREDIT Digestmaximum jicaNo ratings yet

- BUS ORG Partnership CompleteDocument197 pagesBUS ORG Partnership CompleteResci Angelli Rizada-Nolasco0% (1)

- G.R. No. 133632Document1 pageG.R. No. 133632Sherwin Delfin CincoNo ratings yet

- Cordillera Vs SM Case DigestsDocument2 pagesCordillera Vs SM Case DigestsMarie Vera LeungNo ratings yet

- LUCMAN Vs MALAWIDocument2 pagesLUCMAN Vs MALAWIakimo0% (1)

- Loans and Interest RatesDocument1 pageLoans and Interest RatesMichelle CatadmanNo ratings yet

- PNB v. Sps NatividadDocument2 pagesPNB v. Sps NatividadJamMenesesNo ratings yet

- Interest Computation and Nature of Transaction in Bank Loan CaseDocument2 pagesInterest Computation and Nature of Transaction in Bank Loan CaseJerelleen RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 20.) PNB vs. SEDocument2 pages20.) PNB vs. SEMartin RegalaNo ratings yet

- REMEDIAL (En Banc Cases)Document18 pagesREMEDIAL (En Banc Cases)Your Public ProfileNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippine (Complaint) Civil ProDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippine (Complaint) Civil ProEd ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Central Bank vs CA - Partial release of loan amount makes mortgage unenforceable for unreleased amountDocument17 pagesCentral Bank vs CA - Partial release of loan amount makes mortgage unenforceable for unreleased amountMayr Teruel0% (1)

- Republic Planters Bank Vs CADocument2 pagesRepublic Planters Bank Vs CAMohammad Yusof Mauna MacalandapNo ratings yet

- Credit Case DigestDocument10 pagesCredit Case DigestMhayBinuyaJuanzon100% (4)

- Spouses Cuyco v. Spouses Cuyco, GR No. 168736 April 19, 2006Document1 pageSpouses Cuyco v. Spouses Cuyco, GR No. 168736 April 19, 2006franzadonNo ratings yet

- CASE NO. 6 First Metro Investment Corporation v. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc.Document4 pagesCASE NO. 6 First Metro Investment Corporation v. Este Del Sol Mountain Reserve, Inc.John Mark MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs CADocument2 pagesCaltex Vs CAArthur Archie TiuNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank vs. CA 194 Scra 169Document7 pagesMetropolitan Bank vs. CA 194 Scra 169Roselle Manlapaz LorenzoNo ratings yet

- Collection of Sales DigestsDocument34 pagesCollection of Sales DigestsKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Cabagnot v. CSCDocument3 pagesCabagnot v. CSCRaymond RoqueNo ratings yet

- 92 International Finance Corporation v. Imperial Textile MillsDocument2 pages92 International Finance Corporation v. Imperial Textile MillsAgus DiazNo ratings yet

- NHA vs. AlmeidaDocument3 pagesNHA vs. Almeidagianfranco0613100% (1)

- Sales Digest Batch 2Document6 pagesSales Digest Batch 2Joannalyn Libo-onNo ratings yet

- Granada v. PNB (Pamatmat)Document2 pagesGranada v. PNB (Pamatmat)Telle MarieNo ratings yet

- Perez V Monetary BoardDocument4 pagesPerez V Monetary BoardlawNo ratings yet

- Credit Transactions Case DoctrinesDocument14 pagesCredit Transactions Case DoctrinesKobe BullmastiffNo ratings yet

- Diño's Continuing Suretyship LiabilityDocument11 pagesDiño's Continuing Suretyship LiabilityKayeNo ratings yet

- Rule 18 Monzon Vs RelovaDocument2 pagesRule 18 Monzon Vs RelovaManu SalaNo ratings yet

- Sales Digested Case of LeanoDocument4 pagesSales Digested Case of Leanokelela_12018554No ratings yet

- Fide Takers of Insurance and The Public in GeneralDocument2 pagesFide Takers of Insurance and The Public in GeneralRoger Montero Jr.No ratings yet

- Javellana Vs Lim DigestDocument2 pagesJavellana Vs Lim DigestJohnson LimNo ratings yet

- Crisologo-Jose v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 80599, September 15, 1989Document9 pagesCrisologo-Jose v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 80599, September 15, 1989Krister VallenteNo ratings yet

- Sps Cha and Us v. CA and CksDocument3 pagesSps Cha and Us v. CA and CksSNo ratings yet

- CARPO vs. CHUA & DY NG Loan Interest Rate CaseDocument1 pageCARPO vs. CHUA & DY NG Loan Interest Rate CaseLennart ReyesNo ratings yet

- 120 Scra 864Document2 pages120 Scra 864Diana Rose Talibong - AlguraNo ratings yet

- CA rules Presidential Anti-Dollar Salting Task Force not a quasi-judicial bodyDocument4 pagesCA rules Presidential Anti-Dollar Salting Task Force not a quasi-judicial bodyNina CastilloNo ratings yet

- Salvador Chua and Violeta Chua Vs Rodrigo Timan Case DigestDocument1 pageSalvador Chua and Violeta Chua Vs Rodrigo Timan Case DigestMina AgarNo ratings yet

- Nego Week 6 DigestsDocument6 pagesNego Week 6 DigestsRealKD30No ratings yet

- 166 Scra 256Document1 page166 Scra 256Maria QibtiyaNo ratings yet

- TRANSPO Golden NotesDocument42 pagesTRANSPO Golden NotesJoanna Christabelle x. BellezaNo ratings yet

- Dino VS CaDocument2 pagesDino VS CaJulioNo ratings yet

- Manuel Ubas, Sr. vs. Wilson ChanDocument7 pagesManuel Ubas, Sr. vs. Wilson ChanArvy VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Eddie Tamondong For Petitioners. Lope Adriano and Emmanuel Pelaez, Jr. For Private RespondentDocument4 pagesSupreme Court: Eddie Tamondong For Petitioners. Lope Adriano and Emmanuel Pelaez, Jr. For Private RespondentJerommel GabrielNo ratings yet

- Corpo CasesDocument2 pagesCorpo CasesGela Bea BarriosNo ratings yet

- Equitable Pci V FernandezDocument10 pagesEquitable Pci V Fernandezrgtan3No ratings yet

- Saura Import Disputes DBP Loan CancellationDocument9 pagesSaura Import Disputes DBP Loan CancellationAlelie BatinoNo ratings yet

- Eusebio - Calderon Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesEusebio - Calderon Vs PeopleDan Alden ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Court Rules on Validity of Dragnet Clause in Real Estate MortgageDocument10 pagesCourt Rules on Validity of Dragnet Clause in Real Estate MortgageBigs BeguiaNo ratings yet

- Cadiz V CaDocument2 pagesCadiz V CaCarlyn Belle de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Narra Nickel Mining and Development Corp. v. Redmont Consolidated Mines Corp., G.R. No. 195580, 21 April 2014.Document4 pagesNarra Nickel Mining and Development Corp. v. Redmont Consolidated Mines Corp., G.R. No. 195580, 21 April 2014.laraLee100% (1)

- No Interest Due Without Written AgreementDocument5 pagesNo Interest Due Without Written AgreementsophiaNo ratings yet

- Credit - Loan DigestDocument12 pagesCredit - Loan DigestAlyssa Fabella ReyesNo ratings yet

- Gallanosa Vs ArcangelDocument4 pagesGallanosa Vs ArcangelwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Gallanosa Vs ArcangelDocument4 pagesGallanosa Vs ArcangelwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Tacay V RTC TagumDocument2 pagesTacay V RTC TagumwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Lachenal V SalasDocument1 pageLachenal V Salaswesleybooks100% (1)

- Lim vs Saban: Agency Not Revoked When Broker's Efforts Led to Property SaleDocument2 pagesLim vs Saban: Agency Not Revoked When Broker's Efforts Led to Property SalewesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Roque Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesRoque Vs ComelecwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Bier Vs BierDocument1 pageBier Vs BierwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Sumaoang Vs JudgeDocument2 pagesSumaoang Vs Judgewesleybooks100% (1)

- SSC V FavilaDocument2 pagesSSC V FavilawesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Proton V Banque National ParisDocument2 pagesProton V Banque National PariswesleybooksNo ratings yet

- De Castro Vs JBCDocument1 pageDe Castro Vs JBCwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Alzaga Vs SandiganbayanDocument1 pageAlzaga Vs SandiganbayanwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Meneses V SecretaryDocument1 pageMeneses V SecretarywesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Ang Yu Asuncion Vs CADocument3 pagesAng Yu Asuncion Vs CAwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument2 pagesCase DigestwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Claudel Vs CADocument2 pagesClaudel Vs CAwesleybooks100% (2)

- UNION - Maricalum V BrionDocument1 pageUNION - Maricalum V BrionwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Gabatan V CADocument1 pageGabatan V CAwesleybooks100% (1)

- Victorias Milling V CADocument2 pagesVictorias Milling V CAwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Philippine Health Insurance Corp Vs Chinese General Hospital and Medical CenterDocument1 pagePhilippine Health Insurance Corp Vs Chinese General Hospital and Medical CenterwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- GVM Vs NLRCDocument1 pageGVM Vs NLRCwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Mayor vs Macaraig: Removal of Labor Arbiters under RA 6715 UnconstitutionalDocument1 pageMayor vs Macaraig: Removal of Labor Arbiters under RA 6715 UnconstitutionalwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Employer Shall Pay Compensation in The Sums and To The Person Hereinafter Specified. - . (Section 2.)Document1 pageFacts:: Employer Shall Pay Compensation in The Sums and To The Person Hereinafter Specified. - . (Section 2.)wesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Vda de Tupas Vs RTC of Negros OccidentalDocument2 pagesVda de Tupas Vs RTC of Negros OccidentalwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Sumaoang Vs JudgeDocument2 pagesSumaoang Vs Judgewesleybooks100% (1)

- Dong Seung Inc Vs BLRDocument5 pagesDong Seung Inc Vs BLRwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Lim vs Saban: Agency Not Revoked When Broker's Efforts Led to Property SaleDocument2 pagesLim vs Saban: Agency Not Revoked When Broker's Efforts Led to Property SalewesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Roque Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesRoque Vs ComelecwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez Vs HernandezDocument1 pageGutierrez Vs HernandezchiccostudentNo ratings yet

- Vina V CADocument1 pageVina V CAwesleybooksNo ratings yet

- Where To Invest in Africa 2020Document365 pagesWhere To Invest in Africa 2020lindiNo ratings yet

- The Quarters Theory Chapter 1 BasicsDocument11 pagesThe Quarters Theory Chapter 1 BasicsKevin MwauraNo ratings yet

- The Greatest Trade of The CenturyDocument280 pagesThe Greatest Trade of The Centurysalsa94No ratings yet

- Curriculam Vitae: Rohit Kumar GoyalDocument2 pagesCurriculam Vitae: Rohit Kumar GoyalRohit kumar goyalNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets and Institutions PowerPoint SlidesDocument24 pagesFinancial Markets and Institutions PowerPoint Slideshappy aminNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document1 pageAssignment 2foqia nishatNo ratings yet

- Application Summary FormDocument2 pagesApplication Summary Formjqm printingNo ratings yet

- Hablon Production Center Statement of Financial Performance For The Years Ended December 31Document41 pagesHablon Production Center Statement of Financial Performance For The Years Ended December 31angelica valenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Audit Materiality and TolerancesDocument8 pagesAudit Materiality and TolerancesAlrac GarciaNo ratings yet

- Accountancy and Auditing 2-2011Document7 pagesAccountancy and Auditing 2-2011Muhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Mahmood Textile MillsDocument33 pagesMahmood Textile MillsParas RawatNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management (Assignment)Document4 pagesPortfolio Management (Assignment)Isha AggarwalNo ratings yet

- ObjectionDocument10 pagesObjectionMy-Acts Of-SeditionNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceDocument4 pagesMathematical Modeling and Computation in FinanceĐạo Ninh ViệtNo ratings yet

- Dignos V Court of AppealsDocument7 pagesDignos V Court of AppealsJoshua ParilNo ratings yet

- Understanding Natural Gas and LNG OptionsDocument248 pagesUnderstanding Natural Gas and LNG OptionsTivani MphiniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Credit ManagementDocument37 pagesChapter 3 Credit ManagementTwinkle FernandesNo ratings yet

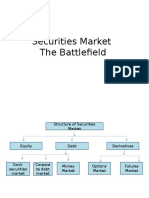

- Securities Market The BattlefieldDocument14 pagesSecurities Market The BattlefieldJagrityTalwarNo ratings yet

- Man Company investment income from Kind CorpDocument12 pagesMan Company investment income from Kind Corpbobo kaNo ratings yet

- Residual Income Model PowerpointDocument29 pagesResidual Income Model Powerpointqwertman3000No ratings yet

- Invoice DocumentDocument1 pageInvoice DocumentAman SharmaNo ratings yet

- Definition of A ChequeDocument2 pagesDefinition of A Chequeashutoshkumar31311No ratings yet

- Central Textile Mills V National Wages CommissionDocument2 pagesCentral Textile Mills V National Wages CommissionPatrick ManaloNo ratings yet

- Bbbscamtrackerannualreport Final 2017Document48 pagesBbbscamtrackerannualreport Final 2017KOLD News 13No ratings yet

- Audit:2auditing Unit 2Document31 pagesAudit:2auditing Unit 2Lalatendu MishraNo ratings yet

- SEC Vs BalwaniDocument23 pagesSEC Vs BalwaniCNBC.comNo ratings yet

- Finance For Non-Financial Managers Final ReportDocument11 pagesFinance For Non-Financial Managers Final ReportAli ImranNo ratings yet

- Level of Financial Literacy (HUMSS 4, Macrohon Group)Document37 pagesLevel of Financial Literacy (HUMSS 4, Macrohon Group)Charyl MorenoNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual Chapter 1Document52 pagesSolution Manual Chapter 1octorp77% (13)

- Project Management Concepts And ClassificationDocument29 pagesProject Management Concepts And Classificationankitgupta16No ratings yet