Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Coyote in Florida

Uploaded by

News-PressCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Coyote in Florida

Uploaded by

News-PressCopyright:

Available Formats

IHR2007-007

________________________________________________________________

The Coyote in Florida

Compiled by Walter McCown and Brian Scheick

Fish and Wildlife Research Institute

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

June 2007

________________________________________________________________

Executive Summary

Coyotes are medium sized canids in the same family as dogs, wolves, and foxes.

They are generally salt and pepper gray or brown with a bushy tail and weigh 9

16 kg (20-35 lbs). Tracks resemble those of dogs. Coyotes are habitat

generalists and use all habitat types in Florida except dense urban areas. They

are opportunistic omnivores, meaning that they eat whatever animal and plant

material is most abundant. Although food items include wild species, conflicts

with humans arise when coyotes prey on domestic animals such as sheep,

goats, chickens, house cats, and consume agricultural products such as

watermelons and cantaloupes.

Coyotes can occur singly, in pairs, or in small family groups depending on habitat

quality and food supply. Home ranges typically average 10 square miles. They

breed once per year during winter months, denning in thickets, brush piles,

hollow logs, or burrows. Litters average 6 pups, and they are weaned at 8 weeks.

Juveniles may disperse long distances in the fall or stay with their parents 2-3

years and provide care for future litters. In years with high food supply, 2 females

in the group may breed, litters are larger, and some young may breed the year

after they are born. Most mortality occurs in the first year of life and may exceed

60%; average life span is 5-6 years. In other areas, wolves and cougars kill them,

but coyotes in Florida have few natural predators besides man. Coyotes can be

legally hunted and trapped year-round, but there is little incentive to do so.

Coyotes should be considered native or naturalized species, not exotics. Fossil

fragments recovered from Florida indicate coyotes occurred in the state as early

as the late Pliocene (2 million years before present), but coyotes disappeared

from eastern North America 12,000 years ago near the end of the last glacial

period. After this period, the red wolf was the only canid in the region until the

late 1920s when habitat loss and persecution (including government programs)

reduced their numbers to near extinction. The extirpation of the wolf and

deforestation of eastern forests opened a niche, and the nonspecific habitat and

food requirements, large litters, short gestation times, and adaptable nature

allowed coyotes to expand eastward. By the 1960s, coyotes had expanded past

the Mississippi river into the Southeast. Although private citizens released

coyotes in a few places around Florida, Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish

Commission (GFC) surveys documented the expansion of coyote populations

IHR2007-007

from the panhandle southward, which suggested natural expansion as the main

source of the current population. In 1983, coyotes were in 18 counties, mostly in

the panhandle, but by 1990 they occupied at least 48 counties. In recent years,

coyotes have been found in all 67 counties of Florida. Evidence suggests that

population levels continue to increase in south Florida, where they recently

arrived.

Coyotes have attacked humans only rarely, and most attacks have resulted in

minor bites or scratches to adults attempting to save their pets. As with many

wildlife species, habituation is a factor but in areas where they are hunted and

trapped, coyotes remain wary of people. Coyote depredation on livestock has

caused conflicts with humans throughout their range and sheep and calf losses

(mainly in western states) amount to millions of dollars each year. In response,

tens of thousands of coyotes are killed annually by landowners and by county,

state, and federal agencies. The United States Department of Agricultures

(USDA) Wildlife Services in Florida remove only 75-100 coyotes per year in

response to livestock depredations, threats to listed species, and potential

collisions with aircraft on airport runways.

Efforts at controlling coyote populations in Florida have been temporary

and localized. Although coyotes now occur statewide, FWC regional offices

receive few complaints about them. Further, livestock losses due to coyotes are

not significant relative to other causes. The Livestock Protection Collar has

been successful in reducing losses but will not be available in Florida until the

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services applies to the

Environmental Protection Agency for approval for its use. Coyotes can cause

damage to certain agricultural crops, but these losses are low as well. The

conflict with potential to affect the greatest number of Floridians and increase the

most in the future is coyote depredation on cats and small dogs. Because

coyotes are often attracted to garbage, the remedies recommended by FWC staff

are the same as for raccoons and bears. While problems with coyotes are

currently low, they can be expected to increase in those areas where coyote

numbers are still increasing. Attempting to completely eliminate coyotes is both

expensive and futile; however, it may be possible to eliminate specific problem

coyotes.

The impact and interactions between coyotes and other species is complex and

dynamic. Because they prey on a wide variety of common species, coyotes are

unlikely to have a significant affect on prey populations. However, predation can

be a concern for listed species that are already in decline, such as beach-nesting

birds and eggs from sea turtles and gopher tortoises. While some evidence

suggests fewer bobcats in areas with coyotes, other studies found no negative

impact and niche separation between the species based on food selection.

Although birds and their eggs make up a small part of a coyotes diet, they prey

on species such as raccoons and foxes that are more abundant and prey more

frequently on birds. By reducing populations of these smaller predators, coyotes

may improve nest success and survival of turkey, quail, and waterfowl. In the

IHR2007-007

absence of red wolves and with panthers restricted to south Florida, coyotes may

fill an important predator niche in most of the state. Furthermore, coyotes also

prey on feral cats and hogs, both species that cause serious ecological damage.

The coyote is classified as a furbearer, and can be legally hunted all year long

with guns, dogs, live traps, or snares. A permit is required to use steel traps, to

trap on another persons property, or to use a gun and light at night. Possessing

or transporting a live coyote requires a Class II captive wildlife permit.

IHR2007-007

Description

The coyote is a member of

the same family (Canidae) as

wolves, foxes and dogs. Coyotes

are about 1-1.5m (3-5 ft) in length;

about 0.6 meters (2 ft) tall and

generally weigh 9 to 16 kg (20-35

lbs). Coyote coloration is most often

a salt and pepper gray or brown,

commonly with a reddish tint and

black animals are occasionally seen.

The tail is thick and bushy, and

generally points downward even

when running. They have large,

erect, triangle-shaped ears and a

long slender muzzle. The coyote is

an extremely lean animal and

appears underfed even when

healthy. Coyote tracks resemble

those of dogs but are more elongate

and compact than dog tracks. Claw

marks are less prominent and middle

claw marks usually converge in

contrast to the splayed pattern

typical of dogs. The coyotes

scientific name, Canis latrans literally

means barking dog, and they

frequently reveal their presence with

a chorus of yipping and howling at

evening or dawn. Coyotes are a

social animal, and these

vocalizations seem to function as a

greeting among individuals.

General Biology

The coyote is a habitat

generalist. In Florida, the coyote

uses all available habitats, including

swamps, dense forest, agricultural

lands, and parks and other green

spaces of cities. The only exception

seems to be dense urban areas.

Coyotes are opportunistic

omnivores, meaning they eat

whatever animal and plant material

is most abundant. Food in Florida

includes prey such as rodents,

rabbits, feral cats, deer (adults and

fawns), insects, opossums,

armadillos, birds, reptiles,

amphibians, hogs, livestock, eggs

(birds and turtles), and carrion and

plant material including palmetto

berries, persimmons, black berries,

wild plums, wild grapes,

cantaloupes, and watermelons.

Conflicts with humans occur when

coyotes prey upon domestic animals

such as sheep, goats, and chickens

and eat agricultural products such as

watermelons and cantaloupes.

Coyote social behavior is shaped

by habitat quality and food supply.

Where food and habitat are plentiful,

coyotes form larger groups.

Generally though, the coyote is less

social than wolves and the basic

social unit is a breeding pair and

their offspring. However, coyotes

can occur singly, in pairs, or in small

family groups. Coyotes are most

active around dusk and dawn.

Coyotes breed only once per

year between January and March.

They are capable of producing fertile

offspring with domestic dogs, but

such pairings are not common in the

wild. Mated pairs may breed for

several consecutive years, but not

necessarily for life. Dens are located

in thickets, brush piles, hollow logs,

or burrows. Gestation lasts about 63

days, and a litter averages 6 (2-12)

pups. Young weigh about 250 g (9

oz.) and are blind and helpless at

birth. Young are cared for by the

mother and occasionally by siblings

from a previous litter. The father and

other males may provide food to

growing young.

IHR2007-007

Pups are weaned at eight weeks

of age but remain with their parents

until fall, when they reach adult

weight. Dispersal by juveniles

usually occurs during fall though

some offspring may stay with their

parents and provide care to future

siblings. Coyotes are capable of

extensive movements and some

dispersing juveniles have traveled

over 160 km (100 miles) from their

birthplace. Home range size

typically averages 3.9 km

2

(10

square miles). In years with high

food supply, litters are larger, 2

females in the family group may

breed, and some 1-year old young

may breed.

Most mortality to coyotes occurs

in the first year of life and frequently

exceeds 60%. Average life span is 5-

6 years in the wild, but maximum

known longevity is 14.5 years.

Coyotes in Florida have few natural

predators besides man, but in other

areas wolves and cougars kill them.

Coyotes can be legally hunted in

Florida all year long, but low pelt

prices provide little incentive for

people to hunt them and most

animals are killed for sport or to

reduce depredation.

Coyote Range in Florida

The first canids in the new

world were relatively small, but they

evolved into increasingly larger

species. The fossil record in Florida

contains canid specimens from the

same family (Canidae) as coyotes

that date from the late Miocene (7

million years before present). This

coyote-like species was eventually

replaced by a small wolf and the

modern coyote did not appear until

the wolf line had grown much larger.

Fossilized skull fragments from the

earliest member of direct coyote

lineage were recovered from the

Sante Fe River in north Florida and

date from the late Pliocene (2 million

years before present). Fossil

records of a species of large wolf

and the coyote disappear from

eastern North America in the late

Pleistocene (15,000 20,000 years

before present) near the end of the

last glacial period at about the time

humans began to inhabit North

America and fossils of the red wolf

(Canis rufus) became evident. From

the late Pleistocene until recent

years, the red wolf appears to be the

only species of wild Canis that was

present in much of the region. It was

described by Bartram in 1791 during

his Florida travels and persisted in

the east until the late 1920s when

habitat loss, broad scale

persecution, government control

programs, intensive hunting and

hybridization with coyotes caused

the near extinction of the red wolf

(Note: the status of the red wolf as a

distinct species remains uncertain.).

Without competition from the larger

red wolf, the coyotes nonspecific

needs in habitat and food, large litter

sizes, short generation time, and the

ability of the species to adapt to

human dominated landscapes they

were able to successfully recolonize

the eastern United States.

By the 1960s, coyotes had

noticeably extended their range

beyond the Mississippi River into

southeastern states. This range

expansion was in part natural, but

was also aided by humans who

imported and released coyotes to be

chased by hounds. Early known

releases in Florida included 2

IHR2007-007

coyotes in Palm Beach County

(1925), 26 in DeSoto County (1925-

1931), and 11 in Gadsden County

(1940s). Coyotes have been noted

in Polk County since at least 1970

shortly after several were released

by a local fox hunter who believed he

was stocking a depleted native fox

population with animals sold to him

as black fox.

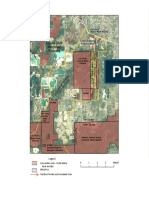

A survey by Florida Game

and Fresh Water Fish Commission

published in 1983 indicated that

coyotes were reliably present in 18

Florida counties, mostly in the

panhandle. The next year, an article

in GFCs periodical, Florida Wildlife,

noted that coyote populations

occurred in two discrete locations; in

the western panhandle (Gadsden

County westward) and in the

Columbia County Hamilton County

area. By 1990 coyotes were present

in at least 48 counties that included

most of the peninsula (Figure 1) and

by 1992 they were occasionally seen

as far south as Collier County (Roy

McBride, personal communication).

A cursory survey of coyote tracks

and other field sign conducted in

south Florida in 1995 found evidence

of coyotes in Polk, Highlands,

Glades, and Hendry counties. In

recent years coyotes have been

noted in all 67 Florida counties but

their presence in the Florida Keys

appears to be restricted to the upper

keys.

Human-Coyote Conflicts

There has been little

systematic documentation of attacks

on humans by coyotes in the eastern

United States. However, in

California, where a more complete

record is available, 89 attacks on

humans took place from 1978

2003 including one fatality of a 3-

year old child. Most of the attacks

occurred in southern California

where approximately 20 million

humans share their living space with

as many as 11 coyotes per square

mile. Most attacks in California

resulted in minor bites and scratches

to adults attempting to intervene in

an attack upon a pet. In areas

where they are hunted or trapped,

coyotes are wary of humans.

However, most attacks occurred in

suburban neighborhoods where

wildlife-loving residents rarely

showed aggression towards coyotes,

allowed them to wander unimpeded

through neighborhoods, and even

fed them on occasion, with the result

that coyotes learned to associate

humans with a dependable source of

food. This association often led to a

sequence of increasingly bold coyote

behaviors that typically preceded

human-coyote contact, including day

and nighttime attacks on pets,

attacks on leashed pets, and chasing

joggers and bicyclists.

Coyote depredation on

livestock has created significant

conflicts with humans. Livestock

losses to sheep and calf producers

amount to millions of dollars each

year, primarily in western states.

Tens of thousands of coyotes are

killed each year by the combined

efforts of private landowners, and

county, state, and federal agencies.

The USDAs Division of Wildlife

Services alone killed more than

75,000 coyotes in 2004. These

efforts are typically only temporary

and localized. In Florida, USDAs

Wildlife Services removes 75 -100

coyotes each year due to livestock

IHR2007-007

depredations, threats to listed

species, and for public safety

reasons around airport runways.

The best example of a large-

scale, concerted effort to eradicate

coyotes occurred in Texas. By the

1950s, a multi-decade organized

effort by woolgrowers in Texas was

successful in creating a coyote free

zone of approximately 24 million

acres in the intensive sheep

producing hill country of central

Texas. It was accomplished only

through a concerted, multi-faceted,

and persistent effort by an army of

ranchers, their employees,

volunteers, and county and state

agencies coincident with a lengthy

drought. This effort was ultimately

thwarted when low prices for wool

and lambs and high labor costs

caused the conversion of a few

sheep ranches in the zone to other

uses not dependant upon predator

removal. By 1973, coyotes were

found in every formerly coyote-free

county.

Although they currently reside

in every county in the state, FWC

regional offices receive very few

complaints regarding coyotes.

Further, losses due to coyotes are

not currently a major concern for

livestock producers in Florida (Jim

Handley, Florida Cattlemens

Association, Andrew Walmsley,

Florida Farm Bureau, personal

communication). Since predation on

livestock is a learned behavior,

ranchers without problems should

consider not removing resident

coyotes. As territorial animals, non-

problem coyotes may prevent other

coyotes that may have learned to

prey on livestock from becoming

established. Should depredations

occur, removing the offending animal

is more efficient than indiscriminate

elimination. In the event that coyote

predation becomes a serious issue

for Florida livestock producers, the

best available remedy is the

Livestock Protection Collar (LP).

The LP collar is manufactured by the

Livestock Protection Company and is

used in many western states as well

as in a number of other countries. It

consists of a bladder filled with

pesticide (sodium fluoroacetate,

Compound 1080) and mounted on a

collar that is affixed to a live animal.

The collar exploits the coyotes usual

predatory focus on the throat of

sheep, goats and calves and

therefore it is a highly selective

method of predator control compared

to leg-hold traps and snares. The

Environmental Protection Agency

has tested the LP collar and found

no secondary toxicity. Use of the

collar in Florida is not currently

permitted pending application by

Florida Department of Agriculture

and Consumer Services to the

Environmental Protection Agency.

However, no application for its use

has been sought by the state. Its

use should be restricted to areas of

the state that are not inhabited by

Florida panthers due to the potential

risk to them.

Perhaps more significant is

the potential impact coyotes have

upon crop agriculture. Among the

many food items eaten by Florida

coyotes are watermelons. Although

Florida growers planted 27,000

acres in watermelons and produced

a crop worth $67 million dollars in

2004, coyotes have not been

reported as a significant nuisance to

Florida watermelon growers (Adam

IHR2007-007

Walmsley, Florida Farm Bureau,

personal communication). Of more

direct significance to most Floridians

is the coyotes established habit of

preying upon domestic cats and

small dogs and their attraction to

garbage. If coyotes become so

numerous around and within human

communities that predation upon

pets and their presence around

dwellings becomes a problem, FWC

personnel will likely be contacted to

alleviate the problem. Many of the

remedies that FWC can suggest to

residents with coyote problems

mirror the technical assistance

currently provided residents

experiencing bear problems.

Problems can be significantly

reduced if residents remove

attractants (garbage, pet food, and

bird seed) and protect their animals

(fencing, secure nighttime housing).

FWC educational materials and

spokespersons should clearly

communicate these prevention

techniques. The emphasis should

be on living with coyotes in the area

rather than eradication.

Attempting to eliminate

coyotes is both expensive and has

proven to be futile. In addition, large

scale eradication may be

ecologically irresponsible because

baits, snares, and leg-hold traps

often kill non-target species.

Furthermore propulsion baits (M-44,

coyote getters) have killed people

and are illegal.

Interactions with native species

Data are lacking to precisely

describe the impact coyotes have on

Floridas wildlife. As a predator, they

impact prey species, and as a

competitor they impact other

carnivores, but both of these

systems are dynamic and complex.

Coyotes are opportunistic and prey

upon many species, but because

their food habits are diverse, coyotes

are unlikely to significantly affect the

population of any single species.

Most of the coyotes common prey

species, such as white-tailed deer,

rodents, and rabbits are common in

most of Florida.

Populations of any species

are lower in the presence of a

competitor, and coyotes usually do

not tolerate the presence of foxes or

bobcats unless food is abundant. A

study of bobcats and coyotes in

Avon Park of South-central Florida

suggested coyotes had no negative

impact on bobcats. Despite

inhabiting similar habitats and

displaying similar activity patterns,

their diets overlapped very little, as

bobcats primarily preyed on rodents

and rabbits and coyotes consumed

primarily large ungulates and large

amounts of fruit. Where the ranges

of both animals overlap coyotes

appear as a common food item of

cougars.

Although localized, coyote

predation can become a concern for

listed species such as the beach-

nesting least tern and black skimmer

and sea turtle and gopher tortoise

eggs. Most of the control efforts by

USDA Wildlife Services in Florida

are along turtle-nesting beaches to

mitigate this (Parker Hall, USDA

Wildlife Services South Region

District Supervisor, personal

communication).

The presence of coyotes in

Florida may have some positive

aspects. Coyotes may fill part of the

niche left vacant when red wolves

IHR2007-007

were extirpated, and they prey on

unwelcome species. Although eggs

of ground-nesting birds are a small

part of the coyotes diet, these birds

may actually benefit from the

presence of coyotes. Coyotes also

prey upon other predators of bird

nests such as raccoons and foxes

that exist at much greater densities

than do coyotes. Coyotes may

reduce numbers of both species

improving survival of turkey, quail,

and waterfowl. In the absence of red

wolves and with panthers restricted

to southern Florida, coyotes fill an

available predator niche in most of

the state.

Coyotes also prey upon feral

cats and hogs. Managing feral cats

is both controversial and difficult, but

the negative impact they have on

birds, small mammals, and reptiles

(including endangered species) and

the competition they constitute for

native carnivores is well

documented. Coyotes can

significantly reduce feral cat

numbers. Feral hogs are known to

cause severe and wide-spread

damage to habitats through their

rooting, and they also prey on

ground nesting species. Coyotes are

not likely to have a major effect on

hog populations, but they do prey on

smaller individuals.

Status of Coyotes in Florida

The seasons and method of

take for coyotes in Florida are very

liberal. The FWC Code Book

classifies coyotes as furbearers

regarding license and tagging

requirements and the seasons of

take (68A-1.004) and as such,

coyotes may be taken throughout the

year using guns, dogs, live traps or

snares (68A-24.002). However,

possession and transport of live

coyotes is prohibited unless

authorized through a captive wildlife

permit from FWC. Coyotes are

Class II captive wildlife (68A-6.002).

There are general FWC

regulations that affect taking

coyotes. No permit is needed to kill

coyotes causing damage to personal

property, and a landowner may use

traps (excluding steel traps) on their

own property to catch coyotes.

Hunting coyotes at night using a gun

and light requires a permit from

FWC, as does trapping coyotes with

steel traps.

Implications

The coyote should be considered a

naturalized, not exotic species

because fossil records indicate that

they occurred in Florida in pre-

historical times and resettled the

state in recent decades primarily on

their own in a natural expansion of

their range. Their presence in

Florida may be somewhat beneficial

through filling the niche left empty by

the eradication of the red wolf, or be

no more harmful than the recently-

arrived cattle egret. Negative effects

of coyotes on native species are less

than those caused by hogs and feral

cats, and depredation upon livestock

is likely less from coyotes than from

feral dogs. Little research is available

to specify the coyotes impacts on

native species, but there is little

reason to surmise a strongly

negative association. Additionally,

coyotes are known to prey on feral

cats, an unwanted species that has

been implicated in significantly

reducing numbers of several species

of small mammals, birds, and

IHR2007-007

rodents. Coyotes may prey on small

hogs, which cause wide-spread

habitat damage, a more serious

threat to native species of animals

and plants in Florida.

IHR2007-007

IHR2007-007

Sources Used

Bekoff, M. 1982. Coyote. Pp 447-459 In: J.A. Chapman and G.A. Feldhamer

(editors) Wild Mammals of North America. The John Hopkins University

Press, Baltimore.

Berta, A. 2001. Fossil wolves, coyotes, and dogs of Florida. Pp 188-225 in R.C.

Hulburt (editor) The fossil vertebrates of Florida. University Press of

Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Brady, J.R., and H.W. Campbell. 1983. Distribution of coyotes in Florida.

Florida Field Naturalist. 11:40-41.

Coates, S.F., M.B. Main, J.J. Mullahey, J.M. Schaefer, G.W. Tanner, M.E.

Sunquist, and M.D. Fanning. 2002. The Coyote (Canis latrans) : Floridas

newest predator. University of Florida IFAS Extension Bulletin WEC 124.

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu.

Conover, M. R. 2002. Resolving human-wildlife conflicts: the science of wildlife

damage management. Lewis Publishers. 418pp.

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. 2004. Florida

Agriculture Statistical Directory 2004. http://www.Florida-

Agriculture.com/pubs/Florida_Agriculture_ Statistical_Directory.

Gese, E.M., and M. Bekoff. 2004. Coyote: Canis latrans. Pp 81-87 in C. Sillero-

Zubiri, M. Hoffman, and D.W. Macdonald (editors) Canids: foxes, wolves,

jackals, and dogs. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland

and Cambridge, U.K.

Green, J.S., F.R. Henderson, and M.D. Collinge. 1994. Coyotes. Pp C-51-76 in

S.E. Hygnstrom, R.M. Timm, and G.E. Larson (editors) Prevention and

control of wildlife damage. United States Department of Agriculture

Animal Damage Control and Great Plains Agricultural Council Wildlife

Committee.

Hall, D. and F. Boyd. 2001. Coyote control Part 1. Wildlife Trends 1:1-5.

Hill, E.P., P.W. Summner, and J.B. Wooding. 1987. Human influences on range

expansion of coyotes in the southeast. Wildlife Society Bulletin 15:521-

524.

Kelly, B.T., A. Beyer, and M.K. Phillips. 2004. Red wolf: Canis rufus. Pp 87-92

in C. Sillero-Zubiri, M. Hoffman, and D.W. Macdonald (editors) Canids:

foxes, wolves, jackals, and dogs. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.

Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, U.K.

Nunley, G.L. 1996. The reestablishment of the coyote in the Edwards Plateau of

Texas. Coyotes in the Southwest: A compendium of our knowledge.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. San Angelo, Texas.

Maehr, D.S., R.T. McBride, and J.J. Mullahey. 1996. Status of coyotes in south

Florida. Florida Field Naturalist 24:101-107.

Main, M. 2004. Monitoring coyote populations in Florida: 2003 annual report of

the statewide scent station survey. Southwest Florida Research and

Education Center, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation,

University of Florida, IFAS, Southwest Research and Education Center

Report No.: SWFREC-IMM-2004.

IHR2007-007

Main, M. B., M. D. Fanning, J. J. Mullahey, D. H. Thornton, and S. Coates. 2001.

Rancher Perceptions of Coyote in Florida. Department of Wildlife Ecology

and Conservation, Florida Cooperative Extension System, University of

Florida, WEC 146. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/UW143.

Nowak, R.M. 1978. Evolution and taxonomy of coyotes and related Canis. Pp

3-16 in M. Bekoff, (editor) Coyotes: biology, behavior, and management.

Academic Press, New York.

Nowak, R.M. 1991. Coyote. Pp 1068-1070 in R.M. Nowak (editor) Walkers

Mammals of the World, Fifth Edition Volume II. Johns Hopkins University

Press. Baltimore, Maryland.

Nowak, R.M. 1992. The red wolf is not a hybrid. Conservation Biology 6:593-

595.

Nowak, R.M. 2002. The original status of wolves in eastern North America.

Southeastern Naturalist 1:95-130.

Phillips, M.K., and V.G. Henry. 1992. Comments on red wolf taxonomy.

Conservation Biology 6:596-599.

Sargeant, A.B., R.J. Greenwood, M. A. Sovada, T.L. Schaffer. 1993. Distribution

and abundance of predators that affect duck production Prairie Pothole

Region. US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service Resource

publication 194.

Sprenkel, C.B. Coyote. 1984. Florida Wildlife July-August, pp 31-33.

Timm, R.M., R.O. Baker, J.R. Bennett, and C.C. Coolahan. 2004. Coyote

attacks: an increasing suburban problem. Proceedings 21

st

Vertebrate

Pest Conference.

Wooding, J.B. and T.S. Hardisky. 1990. Coyote distribution in Florida. Florida

Field Naturalist. 18:12-14.

Young, S.P., and H.H.T.Jackson. 1951. The clever coyote. Wildlife

Management Institute, Washington D.C.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- ComplaintDocument21 pagesComplaintNews-PressNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Speech in ActionDocument160 pagesSpeech in ActionSplashXNo ratings yet

- Endocrine ChartDocument7 pagesEndocrine Chartwjg2882No ratings yet

- From The Archives: Homicide of Betty Jeanette RuppertDocument7 pagesFrom The Archives: Homicide of Betty Jeanette RuppertNews-PressNo ratings yet

- 7 Magic Fish - Fish TycoonDocument4 pages7 Magic Fish - Fish TycoonDwindaHarditya100% (1)

- The Sign of The BeaverDocument13 pagesThe Sign of The Beaverjuan marcos100% (1)

- The Little SquirrelDocument10 pagesThe Little SquirrelNgọc Ngọc100% (10)

- Document review provides concise summariesDocument58 pagesDocument review provides concise summariesClaudia ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Food and DrinksDocument14 pagesLesson Plan Food and DrinksRamona Iuliana Necula50% (2)

- Helping Our Seniors Get The Covid 19 VaccineDocument1 pageHelping Our Seniors Get The Covid 19 VaccineNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Ethics Complaint Credit CardsDocument15 pagesEthics Complaint Credit CardsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Letters of Findings From CCPS To Charles MaurerDocument9 pagesLetters of Findings From CCPS To Charles MaurerNews-PressNo ratings yet

- A Look Back: The 1992 Fort Myers Green WaveDocument33 pagesA Look Back: The 1992 Fort Myers Green WaveNews-PressNo ratings yet

- LCSD COVID-19 Student Release FormDocument2 pagesLCSD COVID-19 Student Release FormNews-PressNo ratings yet

- State of Florida: The Governor Executive NumberDocument3 pagesState of Florida: The Governor Executive NumberNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Signed Paramedicine Agreement With DOH - EsteroDocument32 pagesSigned Paramedicine Agreement With DOH - EsteroNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Helping Our Seniors Get The Covid 19 VaccineDocument1 pageHelping Our Seniors Get The Covid 19 VaccineNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Kitson Proposal For Civic CenterDocument52 pagesKitson Proposal For Civic CenterNews-Press0% (1)

- Lee Health Board of Directors LetterDocument2 pagesLee Health Board of Directors LetterNews-PressNo ratings yet

- North Collier COVID-19 Vaccine MemorandumDocument6 pagesNorth Collier COVID-19 Vaccine MemorandumNews-PressNo ratings yet

- CCPS COVID-19 WaiverDocument2 pagesCCPS COVID-19 WaiverNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Paramedicine Vaccine Administration Memorandum of Agreement Cape CoralDocument29 pagesParamedicine Vaccine Administration Memorandum of Agreement Cape CoralNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Eo 21-46Document2 pagesEo 21-4610News WTSPNo ratings yet

- Publix Pharmacy Covid 19 Vaccine FL Store List Jan 18, 2021Document7 pagesPublix Pharmacy Covid 19 Vaccine FL Store List Jan 18, 2021Michelle MarchanteNo ratings yet

- FHSAA 2020-21 Season OptionsDocument1 pageFHSAA 2020-21 Season OptionsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Dec-01 David Dorsey WatershedMap No ContoursDocument1 pageDec-01 David Dorsey WatershedMap No ContoursNews-PressNo ratings yet

- US Sugar LawsuitDocument26 pagesUS Sugar LawsuitNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Ivey Nelson Response EmailsDocument2 pagesIvey Nelson Response EmailsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Lee Schools Memorandum of UnderstandingDocument15 pagesLee Schools Memorandum of UnderstandingNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Lee Schools Memorandum of UnderstandingDocument15 pagesLee Schools Memorandum of UnderstandingNews-PressNo ratings yet

- FHSAA 2020 Football OptionsDocument3 pagesFHSAA 2020 Football OptionsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Honorable Lisa Davidson 04-27-20Document2 pagesHonorable Lisa Davidson 04-27-20News-PressNo ratings yet

- North Fort Myers High School Family LetterDocument2 pagesNorth Fort Myers High School Family LetterNews-PressNo ratings yet

- A Federal Judge Found Rick Scott Vilified Ex-Broward Elections SupervisorDocument15 pagesA Federal Judge Found Rick Scott Vilified Ex-Broward Elections SupervisorNews-PressNo ratings yet

- US District 24-2018 General Election Ballot ProofsDocument6 pagesUS District 24-2018 General Election Ballot ProofsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- US District 24-2018 General Election Ballot ProofsDocument6 pagesUS District 24-2018 General Election Ballot ProofsNews-PressNo ratings yet

- William "Coot" Ferrell Jr.Document1 pageWilliam "Coot" Ferrell Jr.News-PressNo ratings yet

- NG TubeDocument3 pagesNG TubeKenny JosefNo ratings yet

- Catclass NotesDocument3 pagesCatclass NotesIssac CaldwellNo ratings yet

- March P2 (Q & A) Sem Paper BioDocument13 pagesMarch P2 (Q & A) Sem Paper BioDineish MurugaiahNo ratings yet

- Cryo Fructo Qual KitDocument3 pagesCryo Fructo Qual KitSuryakant HayatnagarkarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3-Using The Simple PresentDocument26 pagesChapter 3-Using The Simple PresentnoravintelerNo ratings yet

- Histology AssignmentDocument4 pagesHistology AssignmentNico LokoNo ratings yet

- A Lenâpe English DictionaryDocument263 pagesA Lenâpe English DictionarynpeyrafitteNo ratings yet

- Collins HaurisDocument27 pagesCollins HaurisjipnetNo ratings yet

- Shakti Precision Components (I) PVT LTD: COVID-19 Preventive Measures - QuizDocument2 pagesShakti Precision Components (I) PVT LTD: COVID-19 Preventive Measures - Quizshrinath bhatNo ratings yet

- Find The Temperature Using CricketsDocument2 pagesFind The Temperature Using CricketsMoreMoseySpeedNo ratings yet

- A - Specialist Catalogue Fall 2019-Web PDFDocument29 pagesA - Specialist Catalogue Fall 2019-Web PDFFelipe YacumalNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Drug TablesDocument6 pagesAnaesthetic Drug TablesNanaNo ratings yet

- Infectios DiseasesDocument183 pagesInfectios DiseasesAnonymous eson90No ratings yet

- Ex Situ Conservation: R.R.Bharathi 2 Yr BiochemistryDocument20 pagesEx Situ Conservation: R.R.Bharathi 2 Yr BiochemistryVishal TakerNo ratings yet

- Does Sastra Prescribes Animal Sacrifices For The Sake of ReligionDocument15 pagesDoes Sastra Prescribes Animal Sacrifices For The Sake of Religionkeshav3kashmiriNo ratings yet

- Pemeriksaan Foto Thorax Pada Anak-AnakDocument29 pagesPemeriksaan Foto Thorax Pada Anak-AnakRenaldy PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Arthropod ParasiteDocument3 pagesArthropod ParasiteJayson Tafalla LopezNo ratings yet

- Case Report: First Report of Orchitis in Man Caused by Brucella Abortus Biovar 1 in EcuadorDocument5 pagesCase Report: First Report of Orchitis in Man Caused by Brucella Abortus Biovar 1 in EcuadorChandra Gunawan SihombingNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 - Lymph and ImmunityDocument13 pagesChapter 14 - Lymph and Immunityapi-220531452No ratings yet

- Saawariya (Draft Working Copy)Document224 pagesSaawariya (Draft Working Copy)busbysemperfiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 843291Document91 pagesNihms 843291Mae PNo ratings yet

- Kirata Varahi StothraDocument4 pagesKirata Varahi StothraSathis KumarNo ratings yet

- EUS教學 (19) 急診超音波在睪丸急症之應用Document58 pagesEUS教學 (19) 急診超音波在睪丸急症之應用juice119100% (1)