Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Capillary Blood Glucose

Uploaded by

Dennis Cobb0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

539 views4 pagesImproving diabetic control can significantly reduce the risk of microvascular complications (kidney, nerve and eye damage) good blood glucose control has been shown to be associated with more favourable clinical outcomes in patients who have acute cardiovascular events. The procedure blood specimens are obtained using a finger pricking device and results are analysed by a near patient blood glucose meter.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentImproving diabetic control can significantly reduce the risk of microvascular complications (kidney, nerve and eye damage) good blood glucose control has been shown to be associated with more favourable clinical outcomes in patients who have acute cardiovascular events. The procedure blood specimens are obtained using a finger pricking device and results are analysed by a near patient blood glucose meter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

539 views4 pagesCapillary Blood Glucose

Uploaded by

Dennis CobbImproving diabetic control can significantly reduce the risk of microvascular complications (kidney, nerve and eye damage) good blood glucose control has been shown to be associated with more favourable clinical outcomes in patients who have acute cardiovascular events. The procedure blood specimens are obtained using a finger pricking device and results are analysed by a near patient blood glucose meter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Wallymahmed M (2007) Capillary blood glucose monitoring. Nursing Standard. 21, 38, 35-38.

Date of acceptance: December 15 2006.

patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes especially

during periods of instability, for example, illness or

frequent hypoglycaemia. Improving diabetic

control can significantly reduce the risk of

microvascular complications (kidney, nerve and

eye damage) in patients with type 1 and type 2

diabetes (Diabetes Control and Complications

Trial (DCCT) Research Group 1993, UK

Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group

1998). In addition, good blood glucose control has

been shown to be associated with more favourable

clinical outcomes in patients who have acute

cardiovascular events such as myocardial

infarction and stroke (Malmberg et al 1995).

The procedure

Blood specimens are obtained using a finger

pricking device and results are analysed by a near

patient blood glucose meter. A variety of meters

are available and to ensure accuracy of results the

manufacturers advice must be followed carefully.

Serious errors, leading to inappropriate

management decisions, have been identified and

the Department of Health (DH) has issued hazard

warnings. These warnings highlight the need

for staff training and formal quality control

programmes (DH 1987, Medical Devices Agency

(MDA) 1996). The MDA (2002) has issued

recommendations for the training of staff using

point of care devices such as blood glucose

meters. These recommendations include

education and training in the following areas:

Knowledge of what results to expect in normal

and abnormal situations.

Correct use of equipment and knowledge of the

consequences of incorrect use.

Instruction in the collection of blood samples

including gaining consent and health and safety

issues.

The importance of documentation of results.

Capillary blood glucose monitoring

may 30 :: vol 21 no 38 :: 2007 35 NURSING STANDARD

BLOOD GLUCOSE levels are normally

maintained within relatively narrow limits at

about 5-7mmol/l (Williams and Pickup 2004).

Insulin and glucagon, produced by the pancreas,

are largely responsible for the regulation of blood

glucose. Insulin is synthesised in and secreted

from the beta cells within the islets of Langerhans.

Insulin levels are low during periods of fasting

with increased stimulated levels in response to

high blood glucose levels, for example, after

meals. Glucagon is secreted by the alpha cells in

response to low blood glucose levels and inhibited

by high blood glucose levels.

Rationale

Capillary blood glucose monitoring is a convenient

way of monitoring blood glucose patterns and can

be a useful aid in guiding treatment changes in

Summary

This article, the first in a series of articles relating to clinical skills

in nursing, outlines the procedure of capillary blood glucose

monitoring. This is a convenient way of monitoring blood glucose

patterns and can be a useful aid in guiding treatment changes in

patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, especially during periods

of illness or frequent hypoglycaemia.

Author

Maureen Wallymahmed is nurse consultant, Aintree Hospitals NHS

Trust, Diabetes Centre, Walton Hospital, Liverpool.

Email: maureen.wallymahmed@aintree.nhs.uk

Keywords

Blood glucose monitoring; Clinical procedures; Diabetes;

Hyperglycaemia; Hypoglycaemia

These keywords are based on the subject headings from the British

Nursing Index. This article has been subject to double-blind review.

For author and research article guidelines visit the Nursing Standard

home page at www.nursing-standard.co.uk. For related articles

visit our online archive and search using the keywords.

If you would like to contribute to the art and science section contact: Gwen Clarke, art and science editor, Nursing Standard,

The Heights, 59-65 Lowlands Road, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex HA1 3AW. email: gwen.clarke@rcnpublishing.co.uk

p35-38w38 22/5/07 2:21 pm Page 35

A knowledge of the meters limitations and

when use is contraindicated.

An in-depth knowledge of the individual

meter, including error codes, calibration and

quality control techniques.

Staff performing blood glucose monitoring should

also be involved in a formal quality control

programme. This involves performing and

documenting quality control checks in the clinical

area using specific high and low quality control

solutions on a daily basis. This is known as

internal quality control. External quality control

programmes should also be in operation. These

involve solutions of an unknown glucose level

being sent from the laboratories to the clinical

areas on a regular basis. Each user should perform

a quality control test and return the result to the

laboratory. In this way inaccurate performance

can be identified and additional training arranged.

Each trust has a responsibility to develop and

implement a training and quality control

programme for all staff performing capillary

blood glucose monitoring.

Indications Capillary blood glucose monitoring

is indicated in the following situations:

Day-to-day management of patients with type

1 and type 2 diabetes.

Detection of hypoglycaemia.

Detection of persistent hyperglycaemia, for

example, during periods of illness.

Management of acute complications of

diabetes causing metabolic decompensation,

for example, diabetic ketoacidosis and

hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma (once severe

dehydration is corrected).

Management of patients during periods of

fasting, for example, surgery when a glucose-

potassium-insulin regimen may be required.

It is important to note that a diagnosis of diabetes

should not be made on the basis of a capillary

blood glucose measurement obtained using a

blood glucose meter. While meters are

convenient and readily available, there is

potential for error and the diagnosis should be

confirmed on a laboratory specimen. Blood

glucose levels for the diagnosis of diabetes and

other categories of glucose intolerance have been

agreed by the World Health Organization

(Alberti and Zimmet 1998). In the UK it is

estimated that there are currently more than two

million people with diagnosed diabetes and up

to 750,000 who have diabetes but are not yet

diagnosed (Diabetes UK 2006). Other possible

indications for capillary blood glucose

monitoring:

Patients taking medications such as steroids

and atypical antipsychotics which can cause

blood glucose levels to rise.

Specific situations, for example, parenteral

feeding which can lead to a rise in blood

glucose levels.

Contraindications Staff performing capillary

blood glucose monitoring should be aware that

the accuracy of results can be affected by the

following clinical conditions (MDA 1996):

Peripheral circulatory failure and severe

dehydration, for example, diabetic

ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma,

shock and hypotension. In these situations

capillary blood glucose readings can be

artificially low due to peripheral shut down.

Haematocrit values above 55% may lead to

inaccurate results if the blood glucose level

is more than 11mmol/l.

Intravenous (IV) infusion of ascorbic acid.

Pre-eclampsia.

Some treatments for renal dialysis.

Hyperlipidaemia cholesterol levels above

13mmol/l may lead to artificially raised

capillary blood glucose readings.

Capillary blood glucose monitoring should only

be performed by staff who have undergone

formal training as agreed by each trust (Table 1).

Hypoglycaemia:low blood glucose

Hypoglycaemia occurs when blood glucose

levels fall below 4mmol/l and should be treated

promptly. It can occur in patients on insulin and

sulphonylureas. Causes of hypoglycaemia

include missed or late meals, not eating enough,

taking too much insulin or tablets, exercise and

excessive alcohol. Common manifestations

include sweating, shaking, palpitations, hunger

and poor concentration. Hypoglycaemia should

be treated with fast-acting carbohydrate, for

example, three to six glucose tablets, 150ml fizzy

drink or 50-100ml Lucozade and followed up

with some longer-acting carbohydrate such as

biscuits or a sandwich. Blood glucose should be

recorded five to ten minutes after treatment.

Severe hypoglycaemia can be managed with

intramuscular glucagon or IV dextrose.

It is important to remember that bedside blood

glucose meters are not always accurate at low

readings and that hypoglycaemia should be

36 may 30 :: vol 21 no 38 :: 2007 NURSING STANDARD

&

art &science clinical skills: 1

p35-38w38 22/5/07 2:21 pm Page 36

may 30 :: vol 21 no 38 :: 2007 37 NURSING STANDARD

TABLE 1

Capillary blood glucose monitoring procedure

Action

Check that the blood glucose meter is ready for use. Ensure the following:

The test strips are in date, have been stored correctly and have not been exposed to

the air (this does not apply to strips that are individually wrapped).

The monitor is calibrated for use* with the pack of strips in use.

If a new pack of strips is required ensure the machine is recalibrated.

Quality control tests (high and low) have been carried out and documented on that day.

*Some meters use test strips that have an automatic calibration system while others

need to be recalibrated when a new pack of strips is opened.

Refer to manufacturers instructions for information.

Ensure that you have the following equipment:

Blood glucose meter (as above).

Test strips.

Finger pricking device or lancets.

Cotton wool.

Sharps disposal container.

Gloves.

Prepare the patient

Describe the procedure to the patient, explain why it is needed, answer any questions and

gain verbal consent. Ask the patient to wash his or her hands in warm, soapy water and dry

thoroughly. Do not use alcohol swabs or rub as this can lead to an inaccurate result. Position

the patient comfortably.

Wash your hands and put on protective gloves

Take a sample of blood

Using a single use, retractable lancet take a sample from the side of the finger. If the finger

does not bleed readily, milk the finger until enough blood is obtained. Most strips need only

a small volume of blood for accurate testing (0.3-4l).

Apply the blood to the test strip

Most strips are now hydrophilic. The tip of the strip is gently applied to the drop of blood

and the blood is sucked up automatically, stopping when the correct volume of blood has

been obtained. However, some strips still require the blood to be dropped directly onto the

reagent strip.

Dispose of the lancet in the sharps disposal container

When the result is available record on the appropriate charts/nursing documentation

Dispose of waste, for example, gloves and cotton wool, appropriately

Observe the test site for bleeding, ensure that the patient is comfortable and explain the

result as required

Report any unexpected, out of range results to the nurse in charge

Results that are outside the expected range for an individual patient should be reported to

the nurse in charge and appropriate action taken.

Rationale

To ensure maximum efficiency, patient

comfort and safety.

To reduce anxiety and ensure that the

patient is aware of the reasons for

blood glucose monitoring.

To prevent cross-infection and reduce

the risk of contamination.

A single use retractable lancet is

recommended to reduce the risk of

needlestick injury and cross-infection.

The side of the finger is generally less

sensitive than the tip and sensitivity in

tips of fingers may be lost if used

regularly. Rotation of sites is advised

to avoid over use of one site as the

skin may become hard and painful.

To obtain an accurate blood

glucose measurement.

To reduce the risk of needlestick injury

and cross-infection.

To ensure accurate recording of results

which may influence management.

To reduce the risk of cross-infection.

To ensure that the patient is

comfortable and aware of the blood

glucose result. This is important

because many patients self-monitor

blood glucose at home and make

adjustments to insulin accordingly.

To ensure patient safety.

p35-38w38 22/5/07 2:21 pm Page 37

considered in patients with typical symptoms.

Diabetic treatment should not be omitted because

of a single hypoglycaemic episode; the

hypoglycaemia should be treated and the usual

medication given. However, if hypoglycaemia

occurs frequently a review of the patients

treatment should be sought.

Hyperglycaemia:raised blood glucose

Intercurrent illness can have an effect on

glycaemic control causing blood sugars to rise

and can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis especially

in patients with type 1 diabetes. If blood glucose

is persistently raised, the patients urine should

be tested for ketones and advice sought from

the diabetes team. If vomiting and diarrhoea

are present, dehydration can occur quickly

and advice should be sought. Other causes of

hyperglycaemia include systemic steroids,

dietary factors, non-concordance with

medication and stress.

Frequency of monitoring

All hospital inpatients with diabetes need regular

blood glucose monitoring because acute illness

can seriously affect blood glucose levels. The

frequency of monitoring should be decided on an

individual patient basis depending on the clinical

condition. However, on admission to hospital it

is advisable to monitor capillary blood glucose

four times a day pre-meal and pre-bed for 48

hours and then to review the frequency of

monitoring according to the results and the

patients condition. Patients being cared for at

home should have blood glucose monitoring

according to individual need.

Glycosylated haemoglobin

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA

1c

) is a

measurement of long-term diabetic control. This

blood test measures the percentage of

haemoglobin bound to glucose and is useful as it

reflects about two to three months of blood

glucose control. Target HbA

1c

levels are

6.5-7.5% depending on individual

circumstances, for example, complications

(National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2002,

2004). In addition to HbA

1c

and capillary blood

glucose monitoring, the following should be

considered when monitoring control: symptoms,

frequency of hypoglycaemia and weight. As

acute illness can adversely affect blood sugar

control, it is useful for all inpatients with diabetes

to have a HbA

1c

blood test while in hospital.

Conclusion

Capillary blood glucose monitoring is a useful

tool in the management of patients with diabetes.

However, there is potential for serious error if the

procedure is not followed correctly. All staff

performing capillary blood glucose monitoring

should be trained and assessed according to trust

policy, be aware of what results to expect and

when to seek advice NS

38 may 30 :: vol 21 no 38 :: 2007 NURSING STANDARD

&

art &science clinical skills: 1

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ (1998)

Definition, diagnosis and

classification of diabetes mellitus

and its complications. Part 1:

diagnosis and classification of

diabetes mellitus provisional report

of a WHO consultation. Diabetic

Medicine. 15, 7, 539-553.

Department of Health (1987)

Blood Glucose Measurements:

Reliability of Results Produced in

Extra-laboratory Areas. DHSS

Hazard Notice 15 October. NHS

Procurement Directorate DHSS

Blood Glucose Measurement

Department of Health and Social

Security, London.

Diabetes Control and

Complications Trial Research

Group (1993) The effect of

intensive treatment of diabetes on

the development and progression of

long-term complications in insulin

dependent diabetes mellitus. New

England Journal of Medicine. 329,

14, 977-986.

Diabetes UK (2006) What is

Diabetes? www.diabetes.org.uk/

Guide-to-diabetes/What_is_

diabetes/What_is_diabetes/ (Last

accessed: May 10 2007.)

Malmberg K, Ryden L, Efendic S

et al (1995) Randomized trial of

insulin-glucose infusion followed by

subcutaneous insulin treatment in

diabetic patients with acute

myocardial infarction (DIGAMI

study): effects on mortality at 1

year. Journal of the American

College of Cardiology. 26, 1, 57-65.

Medical Devices Agency (1996)

Extra-laboratory Use of Blood

Glucose Meters and Test Strips:

Contra-indications, Training and

Advice to the Users. Safety Notice

MDA SN 9616. www.mhra.gov.uk/

home/idcplg?IdcService=SS_GET_P

AGE&useSecondary=true&ssDocNa

me=CON2022746&ssTargetNodeId

=420 (Last accessed: May 1 2007.)

Medical Devices Agency (2002)

Management and Use of IVD Point

of Care Test Devices. The Stationery

Office, London.

National Institute for Clinical

Excellence (2002) Management of

Type 2 Diabetes. Management of

Blood Glucose. NICE, London.

National Institute for Clinical

Excellence (2004) Type 1 Diabetes:

Diagnosis and Management of Type

1 Diabetes in Children, Young People

and Adults. NICE, London.

United Kingdom Prospective

Diabetes Study Group (1998)

Intensive blood glucose control with

sulphonylureas or insulin compared

with conventional treatment and

risk of complications in patients

with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33).

The Lancet. 352, 9131, 837-853.

Williams G, Pickup JC (Eds)

(2004) Handbook of Diabetes. Third

edition. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

References

p35-38w38 22/5/07 2:21 pm Page 38

You might also like

- Impaired Tissue Perfusion Related To The Weakening / Decreased Blood Flow To The Area of Gangrene Due To Obstruction of Blood VesselsDocument3 pagesImpaired Tissue Perfusion Related To The Weakening / Decreased Blood Flow To The Area of Gangrene Due To Obstruction of Blood VesselsKat AlaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument49 pagesCase StudyLennie Marie B Pelaez100% (1)

- CystoclysisDocument2 pagesCystoclysisRaymond BasiloniaNo ratings yet

- Mcdonald Case StudyDocument12 pagesMcdonald Case StudyJohn WickNo ratings yet

- NCP Micu Hascvd Cad - RioDocument5 pagesNCP Micu Hascvd Cad - RioRio BonifacioNo ratings yet

- A Project Proposal On Case Study and Management of A Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus ClientDocument6 pagesA Project Proposal On Case Study and Management of A Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus ClientMichael Kivumbi100% (3)

- Recurrent PAF Case StudyDocument3 pagesRecurrent PAF Case StudyDanae Kristina Natasia BangkanNo ratings yet

- Blood Glucose MonitoringDocument30 pagesBlood Glucose MonitoringVictoria Castillo TamayoNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors and Treatments for Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument3 pagesRisk Factors and Treatments for Alzheimer's DiseaseKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isNo ratings yet

- Alc Intra1 Questionnaire HypertensiveDocument5 pagesAlc Intra1 Questionnaire HypertensiveAndrea Blanca100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan for Patient with Risk of BleedingDocument11 pagesNursing Care Plan for Patient with Risk of BleedingKimsha ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- HemodialysisDocument2 pagesHemodialysisJanelle MarceraNo ratings yet

- Medication and Health Teaching Discharge PlanDocument1 pageMedication and Health Teaching Discharge PlanBernalene SyNo ratings yet

- Drug Study On DigoxinDocument8 pagesDrug Study On DigoxinDonald BidenNo ratings yet

- Health TeachingDocument3 pagesHealth TeachingNyj QuiñoNo ratings yet

- Different Iv FluidsDocument2 pagesDifferent Iv FluidsBeverly DatuNo ratings yet

- CBI Procedure Guide for NursesDocument9 pagesCBI Procedure Guide for NursesAlvin OccianoNo ratings yet

- Giving of Medication 12 RightsDocument41 pagesGiving of Medication 12 RightsLeslie PaguioNo ratings yet

- Bioethical Components of CareDocument2 pagesBioethical Components of CarekeiitNo ratings yet

- Galvus Met TabDocument23 pagesGalvus Met TabMaria Nicole EconasNo ratings yet

- Selecting the Right IV Catheter SizeDocument1 pageSelecting the Right IV Catheter SizeRafael BagusNo ratings yet

- CNN Practice QuestionsDocument5 pagesCNN Practice QuestionsUri Perez MontedeRamosNo ratings yet

- Capillary Blood Glucose Monitoring or CBG MonitoringDocument5 pagesCapillary Blood Glucose Monitoring or CBG MonitoringRonilyn Mae Alvarez100% (1)

- Urinalysis Procedure & ResultsDocument6 pagesUrinalysis Procedure & ResultsbobtagubaNo ratings yet

- HemodialysisDocument3 pagesHemodialysisReem NurNo ratings yet

- Skill Performance Evaluation - Measuring Intake and OutputDocument2 pagesSkill Performance Evaluation - Measuring Intake and OutputLemuel Que100% (1)

- Nursing Responsibilities For Oxygen AdministrationDocument3 pagesNursing Responsibilities For Oxygen AdministrationJahseh WolfeNo ratings yet

- Ranitidine, ParacetamolDocument3 pagesRanitidine, ParacetamoltaekadoNo ratings yet

- G-CFA Instructor Tab 6-2 Handout 2 Sample Adequate Nursing Care Plan-R6Document2 pagesG-CFA Instructor Tab 6-2 Handout 2 Sample Adequate Nursing Care Plan-R6SriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Gunshot Wound PeritonitisDocument66 pagesGunshot Wound PeritonitisMia Charisse FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal System Disorders NCLEX Practice - Quiz #2 - 50 Questions - NurseslabsDocument52 pagesGastrointestinal System Disorders NCLEX Practice - Quiz #2 - 50 Questions - NurseslabsGypsy Joan TranceNo ratings yet

- IV FluidsDocument1 pageIV FluidsJhensczy Hazel Maye AlbaNo ratings yet

- Metformin Medication Guide - Uses, Side Effects, DosageDocument5 pagesMetformin Medication Guide - Uses, Side Effects, DosageAgronaSlaughterNo ratings yet

- Clinical Example:: What Additional Assessments Would The Nurse Want To Make To Plan Care For This Client?Document2 pagesClinical Example:: What Additional Assessments Would The Nurse Want To Make To Plan Care For This Client?Kim Kristine D. GuillenNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Risks & InterventionsDocument5 pagesPerioperative Risks & InterventionsJellou MacNo ratings yet

- Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Document21 pagesHyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Malueth AnguiNo ratings yet

- Discharge Plan for Stage 4 Lung Cancer and COPDDocument7 pagesDischarge Plan for Stage 4 Lung Cancer and COPDinah krizia lagueNo ratings yet

- DialysisDocument21 pagesDialysisReygie MarsadaNo ratings yet

- Liver Cirrhosis Care PlanDocument3 pagesLiver Cirrhosis Care PlanWendy EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Thoracentesis Reflective EssayDocument2 pagesThoracentesis Reflective EssayAnjae GariandoNo ratings yet

- Operating RoomDocument13 pagesOperating RoomrichardNo ratings yet

- EndocrinedisorderDocument3 pagesEndocrinedisorderDyan LazoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 POST TEST Maternal FrameworkDocument1 pageLesson 1 POST TEST Maternal FrameworkAnnalisa TellesNo ratings yet

- Case PresentationDocument138 pagesCase PresentationrinlopenaiNo ratings yet

- Daily Assignment PlanDocument2 pagesDaily Assignment PlanIvanne HisolerNo ratings yet

- Discharge Plan EndoDocument3 pagesDischarge Plan EndoCharlayne AnneNo ratings yet

- Drug Study Case 1Document37 pagesDrug Study Case 1Maria Charis Anne IndananNo ratings yet

- Nursing Management Pancreatic CancerDocument2 pagesNursing Management Pancreatic CancerKit NameKo100% (2)

- Chapter 1 Fundamental Concepts SPSS - Descriptive StatisticsDocument4 pagesChapter 1 Fundamental Concepts SPSS - Descriptive StatisticsAvinash AmbatiNo ratings yet

- Naso & Orogastric Tube Placement, Testing & FeedingDocument10 pagesNaso & Orogastric Tube Placement, Testing & FeedingYwagar Ywagar100% (1)

- Lowers Abnormal Lipid LevelsDocument34 pagesLowers Abnormal Lipid Levelschelle_morales260% (1)

- Fasting Blood Glucose TestDocument10 pagesFasting Blood Glucose TestBrylle ArbasNo ratings yet

- Anaphylaxis (Case)Document4 pagesAnaphylaxis (Case)drkmwaiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument8 pagesNursing Care PlanVincent QuitorianoNo ratings yet

- NCM 114 RevsDocument8 pagesNCM 114 RevsKryza B. CASTILLONo ratings yet

- Blood GlucoseDocument5 pagesBlood Glucoseediting visualsNo ratings yet

- Laboratory/Diagnostic Exams: WORKSHEET ON Endocrine System DisordersDocument153 pagesLaboratory/Diagnostic Exams: WORKSHEET ON Endocrine System DisorderskdfhjfhfNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Diagnosis and Monitoring Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - SEKAR EMSDocument29 pagesLaboratory Diagnosis and Monitoring Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - SEKAR EMSRaja Iqbal Mulya HarahapNo ratings yet

- Blood Glucose MonitoringDocument11 pagesBlood Glucose MonitoringHannaNo ratings yet

- Sistemik CaranzaDocument9 pagesSistemik CaranzawulanNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Sternal Wound Infections After Open-Heart SurgeryDocument6 pagesTreatment of Sternal Wound Infections After Open-Heart SurgeryDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Managing mediastinitis after cardiac surgeryDocument4 pagesManaging mediastinitis after cardiac surgeryDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Tugas Individu Anggun PDFDocument6 pagesTugas Individu Anggun PDFAnggun PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Assessment Constipation PDFDocument6 pagesAssessment Constipation PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- APGARDocument1 pageAPGARblazegomezNo ratings yet

- User Training AED ProDocument46 pagesUser Training AED ProDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Trend Management Patient of Transposition Great ArteryDocument3 pagesTrend Management Patient of Transposition Great ArteryDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Assessment Constipation PDFDocument6 pagesAssessment Constipation PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Content 8902 PDFDocument6 pagesContent 8902 PDFabdulNo ratings yet

- Arf Post CabgDocument19 pagesArf Post CabgDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Fluid Afterload After CabgDocument6 pagesFluid Afterload After CabgDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Autonomy of Nurse PDFDocument8 pagesAutonomy of Nurse PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Respiration Disorder PDFDocument14 pagesRespiration Disorder PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Transient Ischemic PDFDocument8 pagesTransient Ischemic PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Post Cardiac ComplicationsDocument6 pagesPost Cardiac ComplicationsGull GillNo ratings yet

- CPR Nurse LawDocument6 pagesCPR Nurse LawIpar DayNo ratings yet

- Early Postopcare After Cardiac Surgery PDFDocument23 pagesEarly Postopcare After Cardiac Surgery PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Liver Cirrhosis PDFDocument9 pagesLiver Cirrhosis PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment PDFDocument4 pagesCognitive Impairment PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Avian InfluenzaDocument6 pagesAvian InfluenzaDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Autonomy of Nurse PDFDocument8 pagesAutonomy of Nurse PDFDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- ArdsDocument7 pagesArdsIpar DayNo ratings yet

- Avian InfluenzaDocument6 pagesAvian InfluenzaDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Best Practice in The Use of SpirometryDocument6 pagesBest Practice in The Use of SpirometryDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ArrhythmiaDocument5 pagesCardiac ArrhythmiaDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Atrial FibrilationDocument10 pagesAtrial FibrilationDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Heart NotesDocument13 pagesHeart NotesDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Marfan's Syndrome Signs and Symptoms: EtiologyDocument3 pagesMarfan's Syndrome Signs and Symptoms: EtiologyDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Avian InfluenzaDocument6 pagesAvian InfluenzaDennis CobbNo ratings yet

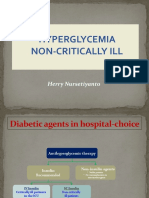

- Non-Critically Ill Hyperglycemia ManagementDocument39 pagesNon-Critically Ill Hyperglycemia ManagementHerry KongkoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Pharmacist Insulin Management On Hemoglobin A1c in Outpatient Hospital Clinic SettingDocument7 pagesImpact of Pharmacist Insulin Management On Hemoglobin A1c in Outpatient Hospital Clinic SettingSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring Devices For Patients With Diabeles Mellitus On InsulinDocument25 pagesContinuous Glucose Monitoring Devices For Patients With Diabeles Mellitus On InsulinCalifornia Technology Assessment ForumNo ratings yet

- Insulin Therapy Guide 2Document3 pagesInsulin Therapy Guide 2AimanRiddleNo ratings yet

- DR Bernstein SolutionDocument7 pagesDR Bernstein Solutionev.adilsonNo ratings yet

- Handy Health Guide To DiabetesDocument49 pagesHandy Health Guide To DiabetesDiabetes Care100% (1)

- Hypoglycemia - Prevention - Practi2 NewDocument17 pagesHypoglycemia - Prevention - Practi2 NewfitrianiNo ratings yet

- Management of Diabetic Cats With Long Acting InsulinDocument16 pagesManagement of Diabetic Cats With Long Acting Insulindia_dianneNo ratings yet

- OBAT INJEKSI AmyDocument4 pagesOBAT INJEKSI AmyKlinik MMCNo ratings yet

- Clinical Learning Log 3 Go Solo - Docx-1Document11 pagesClinical Learning Log 3 Go Solo - Docx-1JezraleFame AntoyNo ratings yet

- Quick Reference Guide - Management of Diabetes 1 2022 Version FINALDocument20 pagesQuick Reference Guide - Management of Diabetes 1 2022 Version FINALHigh Class Education (H.C.Education)No ratings yet

- Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus T2 - Samir RaflaDocument35 pagesTreatment of Diabetes Mellitus T2 - Samir Raflasamir raflaNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Sharon Angelica C (2295015)Document34 pagesJournal Reading Sharon Angelica C (2295015)Sharon Angelica CarolineNo ratings yet

- 852-Article Text-1782-1-10-20221103Document11 pages852-Article Text-1782-1-10-20221103ritaNo ratings yet

- Disclosure: Complex Case: Complications After Cardiac Surgery - Glucose, Sedation and ThrombocytopeniaDocument27 pagesDisclosure: Complex Case: Complications After Cardiac Surgery - Glucose, Sedation and ThrombocytopeniaEnrique SánchezNo ratings yet

- Guidelines and Protocols Of: Diabetes EmergenciesDocument36 pagesGuidelines and Protocols Of: Diabetes Emergenciesyassen hassanNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus Study GuideDocument5 pagesDiabetes Mellitus Study Guiderr5633No ratings yet

- Addressing Hypoglycemia in Type 1 DiabeticsDocument2 pagesAddressing Hypoglycemia in Type 1 DiabeticsTina WuNo ratings yet

- Media Video Makanan Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Kepatuhan Diet Serta Pengendalian Kadar Glukosa Darah Pasien Diabetes Melitustipe IIDocument7 pagesMedia Video Makanan Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Kepatuhan Diet Serta Pengendalian Kadar Glukosa Darah Pasien Diabetes Melitustipe IIpricillia sambekaNo ratings yet

- BMC Endocrine Disorders: Exploring How Patients Understand and Assess Their Diabetes ControlDocument31 pagesBMC Endocrine Disorders: Exploring How Patients Understand and Assess Their Diabetes Controlmaha altweileyNo ratings yet

- (MM2016-3-73) Artur Chwalba, Ewa Otto-Buczkowska: Nowe, Pediatryczne Wskazania Do Stosowania Metforminy - Systematyczny PrzeglądDocument6 pages(MM2016-3-73) Artur Chwalba, Ewa Otto-Buczkowska: Nowe, Pediatryczne Wskazania Do Stosowania Metforminy - Systematyczny PrzeglądTowarzystwo Edukacji TerapeutycznejNo ratings yet

- Farmakologi DMDocument41 pagesFarmakologi DMZainul MuttaqinNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis Case StudyDocument6 pagesDiabetic Ketoacidosis Case StudyJohn AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Diabetis 2Document33 pagesDiabetis 2Fercho MedNo ratings yet

- Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre ReportDocument1 pageShaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre ReportusmannnnNo ratings yet

- A Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Self Administration of Insulin Injection Among Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Rural Area at DehradunDocument5 pagesA Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Self Administration of Insulin Injection Among Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Rural Area at DehradunEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Jcem 0709Document20 pagesJcem 0709Rao Rizwan ShakoorNo ratings yet

- Diabetes 101 - An Overview of Diabetes and Its Management - Michael SeeDocument88 pagesDiabetes 101 - An Overview of Diabetes and Its Management - Michael SeeSangar MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate To Insulin Ratio - Breakfast-Lunch-DinnerDocument5 pagesCarbohydrate To Insulin Ratio - Breakfast-Lunch-Dinnermario rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Deteksi Dini KomplikasiDocument70 pagesDeteksi Dini KomplikasiWiwik Puji LestariNo ratings yet