Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Media Business A Cheaper Times of London Wins Readers

Uploaded by

Aman Anshu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views3 pages,,

Original Title

The Media Business

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document,,

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views3 pagesThe Media Business A Cheaper Times of London Wins Readers

Uploaded by

Aman Anshu,,

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

THE MEDIA BUSINESS

A Cheaper Times of London Wins

Readers

By RICHARD W. STEVENSON

Published: June 13, 1994

In the rough and tumble of the British newspaper business, the decision by The

Times of London last September to lower its newsstand price by a third, to the

equivalent of 45 cents, was greeted with jeers from competitors who predicted the

move would win over few new readers and decimate the paper's profits.

Nine months later, the jeering has stopped, and newspaper publishers and analysts

in Britain and around the world are wondering whether The Times is on to

something. The Times's circulation, which had been declining steadily for years, has

surged beyond even the wildest dreams of its owner, Rupert Murdoch, and its other

executives. According to figures released on Friday by the Audit Bureau of

Circulations, the paper's circulation in May was 517,575, a record high, and 46

percent higher than in August, just before the price cut.

Part of the increase may be attributable to other factors, including a general

resurgence in the economy and a television advertising campaign by the paper last

month. But analysts and even competitors said the price cut, from 45 pence to 30

pence, was the primary reason for the surge in sales.

'Public Relations Triumph'

So far, the strategy has cost Mr. Murdoch and his News Corporation tens of millions

of dollars. Analysts, however, said the paper might be approaching the point where

the higher circulation and a resulting increase in advertising would offset the lost

revenue from the price reduction.

"It hasn't been a financial disaster and it's certainly been a public relations triumph,"

Mark Bielby, an analyst at S. G. Warburg & Company in London, said.

The move seems to have taken some readers from the largest of Britain's three other

general-interest broadsheet papers, The Daily Telegraph, which has since August

seen circulation fall 3 percent, to 993,395 in May. It also appears to have contributed

to a continuing decline at The Independent, the youngest and smallest of the

broadsheet papers. Its circulation in May was 276,660, down 15 percent since

August.

The fourth broadsheet, The Guardian, has seen circulation increase 2.6 percent since

August, to 401,831.

A New Look at Pricing

But the major impact may have been on the industry's assumptions about prices.

British publishers have long assumed that readers, being creatures of habit, are

relatively insensitive to price, at least when it comes to broadsheet papers aiming at

relatively affluent readers.

As a result, most papers have gradually raised prices in recent years -- Mr. Murdoch

bumped the price of The Times from 30 pence to 45 pence between 1990 and 1993 --

and have only rarely dropped prices, believing that a few pennies of savings would

not be enough to lure new readers.

On newsstands, The Times now costs at least one-third less than its main

competitors. The Independent costs 50 pence; The Telegraph, 48 pence, and The

Guardian, 45 pence.

"If you look back at what people said when we began this experiment, almost

everyone said it wouldn't work," Peter Stothard, the editor of The Times, said. "The

truth of the matter is -- and we've been cautious about making too much of it until

now -- that it has worked."

Mr. Stothard said it had become clear that price increases during Britain's deep

recession gave some middle-class readers second thoughts about buying a daily

newspaper. Many of those readers, he said, started buying The Times only a few

times a week instead of every day.

The Times cut its price after watching the experience of another Murdoch-owned

paper here, The Sun, one of London's anything-goes, mass-market tabloids. Tabloid

papers generally have less affluent readerships than broadsheet papers and are thus

more sensitive to price changes.

In July, The Sun began offering a temporary promotional price of 20 pence, or about

30 cents, down from the normal price of 25 pence. Circulation surged, and the

promotional price has been extended indefinitely. The Sun's circulation has jumped

nearly 21 percent since July, to 4.18 million.

Tabloids like The Sun derive about 75 percent of their revenues from circulation,

with the remainder from advertising, analysts said. Among the broadsheets, the

division is about 50-50, they said. In the case of The Times, Mr. Stothard said, the

increase in circulation has made the paper a more attractive vehicle for advertisers.

He declined to provide details.

"The advertising rates are firming very satisfactorily and the volumes are also rising

sharply," he said.

But there is no question that The Times and its parent company, News International,

a subsidiary of the News Corporation, paid a price for the strategy. Largely because of

the price cuts at the newspapers, the News Corporation's operating income in Britain

fell 30 percent, to $218 million (Australian), or about $160 million, in the nine

months that ended March 31, compared with the corresponding period a year earlier.

"This company looks at this as an investment, just as it would look at an investment

in plant or machinery," Mr. Stothard said. "It makes the paper more powerful and

successful."

QUESTIONS

1. What was the price elasticity of demand for The Times? (-1.393)

2. Did the price reduction increase or decrease The Times total revenue from

newspaper sales? (Increased)

3. Was this price reduction profitable for The Times? (No)

4. If not, why did it reduce its price? Under what situation, could this price

reduction be profitable? (To increase the market share and for new customer

acquisition.

5. How did this decision (price reduction) affect the sales of its competitors (Use

cross price elasticity)?

.09,

.078,

.45

You might also like

- Guardian Most Trusted Newspaper in BritainDocument2 pagesGuardian Most Trusted Newspaper in BritainMrs DownieNo ratings yet

- Nonprofit Models for The New York TimesDocument23 pagesNonprofit Models for The New York TimesrivabornmasterNo ratings yet

- The Wall Street Journal, A National Financially Oriented Daily Newspaper - andDocument3 pagesThe Wall Street Journal, A National Financially Oriented Daily Newspaper - andRagini PantNo ratings yet

- Competition Among Newspaper in UKDocument5 pagesCompetition Among Newspaper in UKShaza OzirNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of The British Tabloid PressDocument1 pageDynamics of The British Tabloid PressRichardRooneyNo ratings yet

- Sunday Newspaper Readership Survey Kantar MediaDocument2 pagesSunday Newspaper Readership Survey Kantar MediaKantar MediaNo ratings yet

- Wall Street Journal SubscriptionDocument9 pagesWall Street Journal SubscriptionSamurrick0% (9)

- Open Case - How To Make Money in Newspaper AdvertisingDocument1 pageOpen Case - How To Make Money in Newspaper Advertisingইবনুল মাইজভাণ্ডারীNo ratings yet

- Case Study - New York TimesDocument5 pagesCase Study - New York TimesMichael FinleyNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis May Take Toll On Business MediaDocument3 pagesFinancial Crisis May Take Toll On Business Mediaazaleea_roseNo ratings yet

- Guardian News & Media To Be A Digital-First Organisation: Printing Sponsored byDocument3 pagesGuardian News & Media To Be A Digital-First Organisation: Printing Sponsored bymassimediaNo ratings yet

- History of The TribuneDocument4 pagesHistory of The TribuneCazzac111No ratings yet

- Assignment2 EconomistDocument8 pagesAssignment2 EconomistSarwat KhanNo ratings yet

- Final Report News Media Economic Impact StudyDocument37 pagesFinal Report News Media Economic Impact StudyAlban TabakuNo ratings yet

- Cosmo Revision BookletDocument17 pagesCosmo Revision BookletImmy ParslowNo ratings yet

- Who Killed The NewspaperDocument5 pagesWho Killed The NewspaperLuis Vazquez MoralesNo ratings yet

- The GuardianDocument10 pagesThe GuardianABDUL SHAFINo ratings yet

- 'It's A Ghost Town' - City of London Market Reacts To Covid Slump - Business - The GuardianDocument4 pages'It's A Ghost Town' - City of London Market Reacts To Covid Slump - Business - The GuardianEly PNo ratings yet

- Newspapers - Stabilizing, But Still Threatened - State of The MediaDocument11 pagesNewspapers - Stabilizing, But Still Threatened - State of The MediaThiago SouzaNo ratings yet

- The State of Newspapers: and What It Means For Retail AdvertisersDocument7 pagesThe State of Newspapers: and What It Means For Retail AdvertisersIvie100% (1)

- The Times - PresentationDocument16 pagesThe Times - PresentationAlexandra DobocanNo ratings yet

- Announced: or How To Fund Content Creation in Web 2.0Document3 pagesAnnounced: or How To Fund Content Creation in Web 2.0mediabiteNo ratings yet

- Newspaper 10 2008Document36 pagesNewspaper 10 2008marketing mix magazine100% (1)

- NewspaperDocument72 pagesNewspaperSang PhamNo ratings yet

- Print 21 ReportDocument68 pagesPrint 21 ReportAnkit BansalNo ratings yet

- The Death of The Local Press by Mick Temple, Staffordshire UniversityDocument4 pagesThe Death of The Local Press by Mick Temple, Staffordshire UniversityTHEAJEUKNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Magazine IndustryDocument1 pageOverview of The Magazine Industryecole871No ratings yet

- UK House Prices Fall as Job Losses SurgeDocument6 pagesUK House Prices Fall as Job Losses SurgeTerry JonesNo ratings yet

- NewspaperToday 10 WaysDocument5 pagesNewspaperToday 10 WaysEng. SamNo ratings yet

- Cityam 2011-12-12Document44 pagesCityam 2011-12-12City A.M.No ratings yet

- Why print newspapers remain dominant in Britain despite online's riseDocument4 pagesWhy print newspapers remain dominant in Britain despite online's riseMasudi Buyuk ImamNo ratings yet

- The Guardian Is A British Daily NewDocument1 pageThe Guardian Is A British Daily Newk.szulc12313No ratings yet

- E-Book CPD Log Book 22082017Document4 pagesE-Book CPD Log Book 22082017toekang printNo ratings yet

- Definition and History of NewspapersDocument8 pagesDefinition and History of NewspaperskishankrrishNo ratings yet

- The Iphone 5: Europe Back Incrisis ModeDocument35 pagesThe Iphone 5: Europe Back Incrisis ModeCity A.M.No ratings yet

- Analysis Mode" - Do You Agree ? Why ?Document1 pageAnalysis Mode" - Do You Agree ? Why ?loriNo ratings yet

- Case Study 3: Marketing Strategies for The Wall Street JournalDocument3 pagesCase Study 3: Marketing Strategies for The Wall Street JournalSonia AngrishNo ratings yet

- Better Red Than DeadDocument3 pagesBetter Red Than DeadVisual EditorsNo ratings yet

- Cityam 2012-05-17bDocument35 pagesCityam 2012-05-17bCity A.M.No ratings yet

- News Industry Struggles With Economies of ScaleDocument3 pagesNews Industry Struggles With Economies of ScaleheyNo ratings yet

- Britain and US Agree On Steel Tariffs As Hopes of Broader Trade Deal Recede - International Trade - The GuardianDocument3 pagesBritain and US Agree On Steel Tariffs As Hopes of Broader Trade Deal Recede - International Trade - The GuardianSheila MejíasNo ratings yet

- Newspapers in Times of Low Advertising RevenuesDocument37 pagesNewspapers in Times of Low Advertising RevenuesShikha BansalNo ratings yet

- The Life Cycle of A Free Newspaper Business Model in Newspaper-Rich MarketsDocument19 pagesThe Life Cycle of A Free Newspaper Business Model in Newspaper-Rich MarketsottoviNo ratings yet

- The Life Cycle of NewsDocument23 pagesThe Life Cycle of NewsMangesh KarandikarNo ratings yet

- Future of Local Papers Briefing December 2013Document12 pagesFuture of Local Papers Briefing December 2013ValentinaNo ratings yet

- Business Press Misses Financial MeltdownDocument8 pagesBusiness Press Misses Financial Meltdownwmartin46No ratings yet

- Reimagining Journalism and The Service' Media Business ModelDocument13 pagesReimagining Journalism and The Service' Media Business Modelchanning_j_turnerNo ratings yet

- The Bugle, at Least Until Circulation Increases To Former Levels. The Increased Circulation of The Mercury Will AttractDocument2 pagesThe Bugle, at Least Until Circulation Increases To Former Levels. The Increased Circulation of The Mercury Will AttractDeep VarsaniNo ratings yet

- UN Sable: Good BADDocument23 pagesUN Sable: Good BADCity A.M.No ratings yet

- The Bugle, at Least Until Circulation Increases To Former Levels. The Increased Circulation of The Mercury Will AttractDocument2 pagesThe Bugle, at Least Until Circulation Increases To Former Levels. The Increased Circulation of The Mercury Will AttractDeep VarsaniNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Numbers - Print Media Job Cuts Between 2008-2013 - CMGDocument13 pagesPreliminary Numbers - Print Media Job Cuts Between 2008-2013 - CMGjsource2007No ratings yet

- Case Study - GannettDocument22 pagesCase Study - GannettSuzanne YadaNo ratings yet

- Market Competition Impacts News QualityDocument28 pagesMarket Competition Impacts News QualityMartín Echeverría VictoriaNo ratings yet

- BBC News AssDocument2 pagesBBC News AssVIJIL VIJAYANNo ratings yet

- Comm420-R PefanisDocument14 pagesComm420-R PefanischartemisNo ratings yet

- Situation Analysis of The Wall Street JournalDocument22 pagesSituation Analysis of The Wall Street JournalJm NvNo ratings yet

- How to Write Bids That Win Business: A guide to improving your bidding success rate and winning more tendersFrom EverandHow to Write Bids That Win Business: A guide to improving your bidding success rate and winning more tendersNo ratings yet

- Thomas Piketty's 'Capital in the Twenty-First Century': An IntroductionFrom EverandThomas Piketty's 'Capital in the Twenty-First Century': An IntroductionNo ratings yet

- University Colleges ERPDocument2 pagesUniversity Colleges ERPVudaya KumarNo ratings yet

- Managerial Decision-Making Process ExplainedDocument33 pagesManagerial Decision-Making Process ExplainedAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Fin 1Document43 pagesFin 1Aman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Black HoleDocument37 pagesBlack HoleAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- The Financial Objective in Widely Held CorporationsDocument9 pagesThe Financial Objective in Widely Held CorporationsAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Carnot CycleDocument3 pagesCarnot CycleAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- SADDocument21 pagesSADAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- The Financial Objective in Widely Held CorporationsDocument9 pagesThe Financial Objective in Widely Held CorporationsAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- 4phases of Research Process - HanacekDocument22 pages4phases of Research Process - HanacekMichelle Luba OlsenNo ratings yet

- Zara RetailDocument8 pagesZara RetailAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Plant / Facility LayoutDocument17 pagesPlant / Facility Layoutعبدالله عمرNo ratings yet

- 02 (1) - The Concept of Strategy 1.2Document17 pages02 (1) - The Concept of Strategy 1.2Aman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Lead Time Reduction in Merchandising ProcessesDocument22 pagesLead Time Reduction in Merchandising ProcessesAman Anshu75% (4)

- Are You AlrightDocument1 pageAre You AlrightAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Crompton Greaves: Channel ConflictsDocument3 pagesCrompton Greaves: Channel ConflictsAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Equinox Event Calendar - View Mail Bypass-Aman Our Recruitment. Plan Event Document Form PPT Pgpwe Ask Clubs and Committee Ppts - AmanDocument1 pageEquinox Event Calendar - View Mail Bypass-Aman Our Recruitment. Plan Event Document Form PPT Pgpwe Ask Clubs and Committee Ppts - AmanAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Group2 ITT CaseDocument16 pagesGroup2 ITT CaseAman Anshu100% (1)

- Variance CovarianceDocument1 pageVariance CovarianceAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- DC Location Model Case Electronica - Data For Students AmanDocument15 pagesDC Location Model Case Electronica - Data For Students AmanAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Porters Value ChainDocument3 pagesPorters Value ChainAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Swot AnalysisDocument2 pagesSwot AnalysisAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Measures TestDocument1 pageMeasures TestAman AnshuNo ratings yet

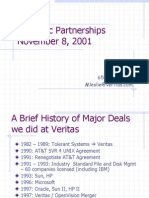

- 0110 Strategic Partnerships1Document26 pages0110 Strategic Partnerships1Aman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Final Reduced Objective Allowable Allowable Cell Name Value Cost Coefficient Increase DecreaseDocument13 pagesFinal Reduced Objective Allowable Allowable Cell Name Value Cost Coefficient Increase DecreaseAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Theory of CostDocument49 pagesTheory of CostAman Anshu100% (1)

- Xiomi and Apple Supply ChainDocument6 pagesXiomi and Apple Supply ChainAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Establishing Contouring Incremental Growth Between Varied Bust SizesDocument33 pagesEstablishing Contouring Incremental Growth Between Varied Bust SizesAman AnshuNo ratings yet

- Bergerac Systems Group 10Document7 pagesBergerac Systems Group 10Aman Anshu0% (1)

- Crowd Behaviour Theories ExplainedDocument25 pagesCrowd Behaviour Theories ExplainedKarthik GpNo ratings yet

- Answer Key of Listening Stratergies - N. T. Sinh - KTC 21 - HANUDocument21 pagesAnswer Key of Listening Stratergies - N. T. Sinh - KTC 21 - HANUNguyen Truong Sinh100% (1)

- The Work (Publication)Document4 pagesThe Work (Publication)Abigail PalasigueNo ratings yet

- List 2017Document55 pagesList 2017seasonNo ratings yet

- Campusjournalism 160209115721Document21 pagesCampusjournalism 160209115721Dungon B JaroNo ratings yet

- TDC II III Practical Examination 2016 PDFDocument3 pagesTDC II III Practical Examination 2016 PDFMUNNA KumarNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Role of NewspapersDocument2 pagesEssay On The Role of NewspapersTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- ASWA Voting Ballots, Oct. 27Document8 pagesASWA Voting Ballots, Oct. 27Montgomery AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- Print Media PPT 120119095156 Phpapp01Document11 pagesPrint Media PPT 120119095156 Phpapp01Divya GuptaNo ratings yet

- InnovationDocument14 pagesInnovationankit_has7190No ratings yet

- Raleigh Mayor Letter To Bankruptcy JudgeDocument2 pagesRaleigh Mayor Letter To Bankruptcy JudgeKate MurphyNo ratings yet

- Newz PaperDocument32 pagesNewz PaperShrey GhosalNo ratings yet

- The Manila Times - Campus Press AwardsDocument2 pagesThe Manila Times - Campus Press AwardsKenneth G. PabiloniaNo ratings yet

- The Cincinnati Enquirer Is A Morning Daily Newspaper PublishedDocument13 pagesThe Cincinnati Enquirer Is A Morning Daily Newspaper PublishedArmandoNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh Media ListDocument23 pagesChandigarh Media ListJuhi Jain100% (1)

- Publication Journalists Contact DetailsDocument48 pagesPublication Journalists Contact DetailsYasin HamidaniNo ratings yet

- Lucknow Media ListDocument3 pagesLucknow Media Liststuti.tocNo ratings yet

- Journalism: National and Campus Newspapers ComparedDocument16 pagesJournalism: National and Campus Newspapers ComparedRhian SecjadasNo ratings yet

- Top UK & US Newspapers by CirculationDocument3 pagesTop UK & US Newspapers by CirculationКатерина Леонідівна ЛяшенкоNo ratings yet

- Compatative Analysis of Business Standard & Economic TimesDocument66 pagesCompatative Analysis of Business Standard & Economic TimesPrashant VermaNo ratings yet

- Parts of A NewspaperDocument7 pagesParts of A NewspaperMelo fi6No ratings yet

- 1077 Vocabulary Test About Newspapers and Magazines Choose The Right Answer MCQ Exercise 164Document3 pages1077 Vocabulary Test About Newspapers and Magazines Choose The Right Answer MCQ Exercise 164Вчитель АнглійськоїNo ratings yet

- MeTC DirectoryDocument3 pagesMeTC Directoryprinsesa0810No ratings yet

- Foreign Tours of Indian Prime MinistersDocument27 pagesForeign Tours of Indian Prime Ministersभक्त योगी आदित्यनाथ काNo ratings yet

- 1 Newspapers Broadsheets Vs Tabloids Article Vocabulary WorksheetDocument1 page1 Newspapers Broadsheets Vs Tabloids Article Vocabulary WorksheetMonika SłupkowskaNo ratings yet

- Page 3 - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument15 pagesPage 3 - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaksadfksadhNo ratings yet

- Analysing Newspapers: A Critical EyeDocument6 pagesAnalysing Newspapers: A Critical EyeFerida TasholliNo ratings yet

- PRIORITY LAND ACQUISITIONDocument27 pagesPRIORITY LAND ACQUISITIONHappy HourNo ratings yet

- All Hindi Newspapers PDFDocument3 pagesAll Hindi Newspapers PDFAbhishek DwivediNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis Between Hindustan Times and Times of IndiaDocument10 pagesComparative Analysis Between Hindustan Times and Times of IndiaARUNA SHARMA33% (3)

- Payment PDFDocument68 pagesPayment PDFanupam kamble100% (1)