Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taxation Law II Case Digest on United States v. Wells

Uploaded by

StradivariumOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taxation Law II Case Digest on United States v. Wells

Uploaded by

StradivariumCopyright:

Available Formats

TAXATION LAW II | B2015

CASE DIGESTS

United States v. Wells

April 13, 1931

Chief Justice Hughes

Raeses, Roberto Miguel O.

SUMMARY: John W. Wells, a resident of Menominee, Michigan, died

on August 17, 1921. The Commissioner of Internal Revenue assessed

additional estate taxes, upon the ground that certain transfers by the

decedent within two years prior to his death, were made in

contemplation of death and should be included in the taxable estate

under the provisions of 402(c) of the Revenue Act of 1918, 40 Stat.

1057, 1097. The amount of the additional tax was paid by the

executors and claim for refund was filed. The claim having been

rejected, the executors brought this suit in the Court of Claims to

recover the amount paid. The Court of Claims decided in favor of the

executors. The US SC affirmed the ruling of the Court of Claims.

DOCTRINE: Whether a gift inter vivos was made "in contemplation of

death" within the meaning of the Revenue Act of 1918 depends upon

the donor's motive, to be determined in each case from the

circumstances, including his bodily and mental condition.

A gift is made "in contemplation of death" when the motive inducing it

is of the sort that leads to testamentary disposition, but not when the

motive is merely to attain an object desirable to the donor in his life,

as where the immediate and moving cause of transfers was the

carrying out of a policy, long followed by the decedent in dealing with

his children, of making liberal girts to them during his lifetime.

A transfer may be "in contemplation of death" though not induced by

a fear that death is near at hand.

FACTS: John W. Wells, a resident of Menominee, Michigan, died on

August 17, 1921. The decedent died at the age of seventy-three years;

his wife and five children, three sons and two daughters, survived him.

As early as 1901, Wells made advancements of money and other

property to his children. He kept a set of books on which he charged to

his children some, but not all, of the amounts transferred to them. Wells

believed that the proper thing to do was to give to his children

substantial sums of money during his lifetime while he could advise

with them as to its proper use. He wanted to know what his children

would do with the money so he knew what he would do with the

balance when he died.

On January 1, 1921, after carefully examining his accounts in preparing

for the final equalization of the prior advancements, decedent

transferred to his children 68,985 shares of the stock of the Girard

Lumber Company.

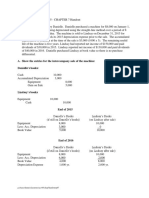

The transfers which the Commissioner deemed to be subject to the

additional estate tax are these:

(1) That of December, 1919, to his sons Daniel and Artemus, of 416

shares of the stock of the J. W. Wells Lumber Company, increased

by a subsequent stock dividend to 1,280 shares at the date of the

decedent's death;

(2) That of January 1, 1921, to his children, of 68,985 shares of the

stock of the Girard Lumber Company:

(3) That of January 26, 1921, in trust for his wife and children, of 3,713

shares of the stock of the Lloyd Manufacturing Company.

The aggregate value at the time of the decedent's death of all the

property embraced in these transfers was $782,903. Excluding this

property, the value of decedent's estate at the time of his death was

$881,314.61, on which the decedent's annual income was

approximately $50,000 a year.

The Court of Claims made detailed findings as to the state of decedent's

health.

(1) Some time prior to the year 1919, Wells had suffered from attacks

of asthma.

(2) In May of that year, he went to a hospital in Chicago for treatment,

and remained eleven days.

(3) About the middle of April, 1920 he began to be afflicted with

ulcerative colitis, a condition in which the large intestine becomes

inflamed. This was a curable disease.

TAXATION LAW II | B2015

CASE DIGESTS

(4) In June, 1920, Wells was advised by physicians in California that he

was suffering from cancer of the intestines.

(5) In the following July, WElls again entered the hospital in Chicago

and, on an examination by a specialist in diseases of the bowels, the

case was diagnosed as ulcerative colitis.

(6) Between July and September, 1920, decedent was informed in

detail of his condition. His physician told him that "he would get

well."

(7) While at the hospital, following an inquiry by a business associate

as to whether had made any agreement with his second wife

regarding the division of property, Wells made an agreement

providing that his wife "should have $100,000 in money and

certain other property in lieu of her statutory and dower rights."

(8) Mrs. Wells ratified all gifts made by the decedent to his children

and all gifts which might be made to his children thereafter "and

before his death whether any of such gifts be made in

contemplation of his death or otherwise." Pursuant to the

agreement, Wells made his will on August 18, 1920, the provisions

of which differed only slightly from those of an earlier will. After

providing for the payment of $100,000 to his widow and making

other bequests, decedent devised his residuary estate to his five

children, with the proviso hat the amount shown to be due me from

each of his children severally in accordance with his books at the

time of his death shall be considered advancement made by him to

them from time to time and shall be chargeable to each of them

severally as advancements and shall be deducted from their

respective shares.

(9) On September 14, 1920, decedent wrote to his son Ralph that he

would be absolutely cured if he was careful.

(10) On September 22, 1920, decedent was discharged from the

hospital in an improved condition. He was in excellent health at

that time.

(11) Wells was again admitted to the hospital in Chicago, on November

30, 1920, for the purpose of an operation to relieve his asthma.

His physician stated that, at that time, "he found him to be in good

general condition." With respect to his ulcerative colitis, he had

greatly improved.

(12) On January 26, 1921, the date of the trust agreement (constituting

the last of the transfers in question), he wrote to his son Ralph,

saying that the doctors had pronounced him cured of bowel

troubles even if he would always have asthma.

(13) On February 3, 1921, he left for California, At that time, his

physician said that he was in good health.

(14) But, in April, 1921, while still in California, decedent had such a

recurrence. He consulted a specialist of reputation who, after

examination, informed him that he might have a cancer, and

advised an operation.

(15) In June, 1921, decedent reentered the hospital in Chicago. His

condition proved to be due to a virulent form of infection that failed

to yield to treatment.

(16) Returning to his home, he continued to lose ground, and he died on

August 17, 1921. An autopsy disclosed a severe and extensive

inflammation of the large intestine, with ulceration of the bowel.

The Court of Claims did not find, in terms, that the transfers in

question were not made in contemplation of death and thus not

liable for the additional estate taxes.

(1) The immediate and moving cause of the transfers was the carrying

out of a policy long followed by decedent in dealing with his children

of making liberal gifts to them during his lifetime.

(2) He had consistently followed that policy for nearly thirty years, and

the three transfers in question were a continuation and final

consummation of such policy. In the last transfer, such amounts

were given to his children as would even them up one with another

in the gifts and advancements made to them.

(3) At the time the transfers were made, decedent had no reason to

believe otherwise than, aside from his asthma, he was, for a man of

his age, in ordinary health. While he had gone through a most

serious and painful illness, he had, as he believed, made an almost

complete recovery. He was assured of this fact by his physician, an

eminent specialist in whom he had great confidence.

(4) The best evidence of the state of the decedent's health at the time

the transfers were made is the statement of his doctor. The best

evidence of the decedent's state of mind at that time and the reasons

actuating him in making the transfers are the statements and

expressions of the decedent himself, supported as such statements

are by all the circumstances concerning the transfers.

TAXATION LAW II | B2015

CASE DIGESTS

ISSUE: WON the transfers were done in contemplation of death.

RULING: No, they were not. Therefore, no additional estate tax should

be charged upon these transfers.

RATIO:

Ruling by the Court of Claims:

"Contemplation of death" does not mean that general knowledge of all

men that they must die, but that there must be a present apprehension,

from some existing bodily or mental condition or impending peril,

creating a reasonable fear that death is near at hand, and that such

reasonable fear or apprehension must be the direct or animating cause,

and the only cause of the transfer.

Contention of the United States:

The definition is too narrow; that transfers in contemplation of death

are not limited to those induced by a condition causing expectation of

death in the near future; that the character of such gifts is determined

by the state of mind of the donor at the time they are made, and that the

statutory presumption may be overcome only by proof that the

decedent's purpose in making the gift was to attain some object

desirable to him during his life, as distinguished from the distribution

of his estate as at death.

Ruling by the Supreme Court:

The phrase "in contemplation of death," previously found in state

statutes, was first used by the Congress in the Revenue Act of 1916,

imposing an estate tax. It was coupled with a clause creating a statutory

presumption in case of gifts within two years before death. The

provision was continued in the Revenue Act of 1918, which governs the

present case, and in later legislation.

While the interpretation of the phrase has not been uniform, there had

been agreement upon certain fundamental considerations.

(1) It is recognized that the reference is not to the general

expectation of death which all entertain. It must be a

particular concern, giving rise to a definite motive.

(2) The provision is not confined to gifts causa mortis, which are made

in anticipation of impending death, are revocable, and are defeated

if the donor survives the apprehended peril. The statutory

description embraces gifts inter vivos, despite the fact that they are

fully executed, are irrevocable and indefeasible.

(3) The quality which brings the transfer within the statute is indicated

by the context and manifest purpose. Transfers in contemplation of

death are included within the same category, for the purpose of

taxation, with transfers intended to take effect at or after the death

of the transferor. The dominant purpose is to reach substitutes

for testamentary dispositions, and thus to prevent the evasion

of the estate tax.

(4) As the transfer may otherwise have all the indicia of a valid gift

inter vivos, the differentiating factor must be found in the

transferor's motive. Death must be "contemplated" -- that is, the

motive which induces the transfer must be of the sort which

leads to testamentary disposition.

a. As a condition of body and mind that naturally gives rise to the

feeling that death is near, that the donor is about to reach the

moment of inevitable surrender of ownership, is most likely to

prompt such a disposition to those who are deemed to be the

proper objects of his bounty, the evidence of the existence or

nonexistence of such a condition at the time of the gift is

obviously of great importance in determining whether it is

made in contemplation of death.

(5) The natural and reasonable inference which may be drawn from the

fact that but a short period intervenes between the transfer and

death is recognized by the statutory provision creating a

presumption in the case of gifts within two years prior to death. But

this presumption is rebuttable, and the mere fact that death ensues

even shortly after the gift does not determine absolutely that it is in

contemplation of death. The question, necessarily, is as to the state

of mind of the donor.

(6) As the test, despite varying circumstances, is always to be found in

motive, it cannot be said that the determinative motive is lacking

merely because of the absence of a consciousness that death is

imminent. It is contemplation of death, not necessarily

contemplation of imminent death, to which the statute refers.

TAXATION LAW II | B2015

CASE DIGESTS

(7) If it is the thought of death, as a controlling motive prompting

the disposition of property, that affords the test, it follows that

the statute does not embrace gifts inter vivos which spring from

a different motive. Such transfers were made the subject of a

distinct gift tax, since repealed.

(8) The government is right in its criticism of the narrowness of the

rule laid down by the Court of Claims, in requiring that there be a

condition "creating a reasonable fear that death is near at hand,"

and that "such reasonable fear or apprehension" must be "the only

cause of the transfer. It is sufficient if contemplation of death be

the inducing cause of the transfer whether or not death is

believed to be near.

(9) The court [of claims] regarded the transfers in question as "a

continuation and and final consummation of such policy," saying

"that this was the motive which actuated the decedent in making

these transfers seems unquestioned." In the view of the court as

thus explicitly stated, not only was there no fear at the time of the

transfers that death was near at hand, but the motive for the

transfers brought them within the category of those which, as

described by the government, are intended by the donor "to

accomplish some purpose desirable to him if he continues to live."

DISPOSITIVE: Judgment affirmed.

You might also like

- The Province of Affliction: Illness and the Making of Early New EnglandFrom EverandThe Province of Affliction: Illness and the Making of Early New EnglandNo ratings yet

- TaxRev - 4B - Estate, Donor - S, VAT, Percentage, Excise, DSTDocument76 pagesTaxRev - 4B - Estate, Donor - S, VAT, Percentage, Excise, DSTJeunaj LardizabalNo ratings yet

- Colorado Bank v. Comm'r, 305 U.S. 23 (1938)Document7 pagesColorado Bank v. Comm'r, 305 U.S. 23 (1938)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- US v. Wells Estate Tax Transfers RulingDocument4 pagesUS v. Wells Estate Tax Transfers RulingAlexis Elaine BeaNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong vs. Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192Document3 pagesCuaycong vs. Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192bernadeth ranolaNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong V Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192Document4 pagesCuaycong V Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192PJFilm-ElijahNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Estate of Donald M. Nelson, Deceased, Lena M. Nelson, Respondent-Petitioner, 396 F.2d 519, 2d Cir. (1968)Document9 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue v. Estate of Donald M. Nelson, Deceased, Lena M. Nelson, Respondent-Petitioner, 396 F.2d 519, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tax Case Digest - 7.6.12Document3 pagesTax Case Digest - 7.6.12nicktortsNo ratings yet

- Carolyn S. Volis v. Puritan Life Insurance Company, 548 F.2d 895, 10th Cir. (1977)Document14 pagesCarolyn S. Volis v. Puritan Life Insurance Company, 548 F.2d 895, 10th Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong Vs Cuaycong (1967)Document6 pagesCuaycong Vs Cuaycong (1967)Joshua DulceNo ratings yet

- Plaintiffs-Appellants vs. vs. Defendants-Appellees Benito C Jalandoni M. S. Gomez Hilado & HiladoDocument5 pagesPlaintiffs-Appellants vs. vs. Defendants-Appellees Benito C Jalandoni M. S. Gomez Hilado & HiladoApa MendozaNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong vs. CuaycongDocument6 pagesCuaycong vs. CuaycongAngelica AbalosNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument47 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Riley v. United States, 212 F.2d 692, 4th Cir. (1954)Document9 pagesRiley v. United States, 212 F.2d 692, 4th Cir. (1954)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estate of Arthur H. Hull, Deceased, Central Trust Capital Bank, Kathrine W. Hull and Margaret Hull Daniels, Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 325 F.2d 367, 3rd Cir. (1963)Document5 pagesEstate of Arthur H. Hull, Deceased, Central Trust Capital Bank, Kathrine W. Hull and Margaret Hull Daniels, Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 325 F.2d 367, 3rd Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- WHITING v. The Bank of The United States, 38 U.S. 6 (1839)Document12 pagesWHITING v. The Bank of The United States, 38 U.S. 6 (1839)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cases DonationDocument29 pagesCases DonationellaNo ratings yet

- Mrs. Seena H. Quillin v. Prudential Insurance Company of America, 280 F.2d 771, 4th Cir. (1960)Document9 pagesMrs. Seena H. Quillin v. Prudential Insurance Company of America, 280 F.2d 771, 4th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Property 404 Adraincem v. Bullecer Cabusas Jamero NaresDocument31 pagesProperty 404 Adraincem v. Bullecer Cabusas Jamero NaresJhean NaresNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law Ii Case DigestDocument37 pagesTaxation Law Ii Case DigestAhmed-Adhiem Bahjin KamlianNo ratings yet

- International Arbitral Awards ReportDocument4 pagesInternational Arbitral Awards ReportshedzaNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong V CuaycongDocument36 pagesCuaycong V CuaycongJepz FlojoNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong V CuaycongDocument36 pagesCuaycong V CuaycongJepz FlojoNo ratings yet

- Yeaton and Others v. Lenox and Others., 33 U.S. 123 (1834)Document5 pagesYeaton and Others v. Lenox and Others., 33 U.S. 123 (1834)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- First National Bank at Lubbock, Trustee v. United States, 463 F.2d 716, 1st Cir. (1972)Document8 pagesFirst National Bank at Lubbock, Trustee v. United States, 463 F.2d 716, 1st Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Insurance CasesDocument27 pagesInsurance CasesBianca de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- United States v. Walter R. Conlin, 551 F.2d 534, 2d Cir. (1977)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Walter R. Conlin, 551 F.2d 534, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. William H. Addington, 471 F.2d 560, 10th Cir. (1973)Document12 pagesUnited States v. William H. Addington, 471 F.2d 560, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Succession Case DigestDocument6 pagesSuccession Case DigestTreblif Adarojem0% (1)

- Cuaycong V CuaycongDocument13 pagesCuaycong V CuaycongCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henning, 191 F.2d 588, 1st Cir. (1951)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Henning, 191 F.2d 588, 1st Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Huntington v. IRS, 1st Cir. (1994)Document25 pagesHuntington v. IRS, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cramer v. Wilson, 195 U.S. 408 (1904)Document5 pagesCramer v. Wilson, 195 U.S. 408 (1904)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Connor v. Featherstone, 25 U.S. 199 (1827)Document6 pagesConnor v. Featherstone, 25 U.S. 199 (1827)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Study Guide No. 7 SuccesionDocument4 pagesStudy Guide No. 7 SuccesionLaika CorralNo ratings yet

- United States v. Louis Rifkin, 451 F.2d 1149, 2d Cir. (1971)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Louis Rifkin, 451 F.2d 1149, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nicholson v. INS, 9 F.3d 1535, 1st Cir. (1993)Document4 pagesNicholson v. INS, 9 F.3d 1535, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Whiting v. United States, 231 F.3d 70, 1st Cir. (2000)Document9 pagesWhiting v. United States, 231 F.3d 70, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estate of Lydia G. Maxwell, Deceased First National Bank of Long Island Victor C. McCuaig JR., Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 3 F.3d 591, 1st Cir. (1993)Document18 pagesEstate of Lydia G. Maxwell, Deceased First National Bank of Long Island Victor C. McCuaig JR., Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 3 F.3d 591, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Essilfie and Another v. QuarcooDocument12 pagesEssilfie and Another v. QuarcooISAAC ADUSI-POKUNo ratings yet

- United States v. Mitchell, 403 U.S. 190 (1971)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Mitchell, 403 U.S. 190 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mattingly v. Boyd, 61 U.S. 128 (1858)Document5 pagesMattingly v. Boyd, 61 U.S. 128 (1858)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nichols v. Coolidge, 274 U.S. 531 (1927)Document10 pagesNichols v. Coolidge, 274 U.S. 531 (1927)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Zapanta Et Al V Posadas - PROPERTYDocument1 pageZapanta Et Al V Posadas - PROPERTYLaura R. Prado-LopezNo ratings yet

- Orlo G. Burch and Marjorie C. Burch v. United States, 698 F.2d 575, 2d Cir. (1983)Document8 pagesOrlo G. Burch and Marjorie C. Burch v. United States, 698 F.2d 575, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Bernard W. Coblentz, 453 F.2d 503, 2d Cir. (1972)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Bernard W. Coblentz, 453 F.2d 503, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong Vs CuaycongDocument4 pagesCuaycong Vs CuaycongZahraMinaNo ratings yet

- Rosales vs. Rosales, G.R. No. L-40789, 148 SCRA 59, February 27, 1987Document3 pagesRosales vs. Rosales, G.R. No. L-40789, 148 SCRA 59, February 27, 1987AliyahDazaSandersNo ratings yet

- Argente Vs West Coast Life Insurance Co., 51 Phil. 725, March 19, 1928Document8 pagesArgente Vs West Coast Life Insurance Co., 51 Phil. 725, March 19, 1928BREL GOSIMATNo ratings yet

- Estate of Daniel McNichol Deceased, Ellen McNichol Evangelista and Joseph G. McNichol Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 265 F.2d 667, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document9 pagesEstate of Daniel McNichol Deceased, Ellen McNichol Evangelista and Joseph G. McNichol Executors v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 265 F.2d 667, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Monique G. Caron v. United States, 548 F.2d 366, 1st Cir. (1976)Document8 pagesMonique G. Caron v. United States, 548 F.2d 366, 1st Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Eddie C. Wilson, SR., 81 F.3d 1300, 4th Cir. (1996)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Eddie C. Wilson, SR., 81 F.3d 1300, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estate Tax Case DigestsDocument7 pagesEstate Tax Case DigestsVince Albert TanteNo ratings yet

- Notre Dame University - College of Law Taxation II Course OutlineDocument19 pagesNotre Dame University - College of Law Taxation II Course OutlineLucifer MorningstarNo ratings yet

- Citizenship Rights of Persons Born in the US to Non-Citizen ParentsDocument3 pagesCitizenship Rights of Persons Born in the US to Non-Citizen ParentsmocorruptNo ratings yet

- Eusebio v. Eusebio PDFDocument7 pagesEusebio v. Eusebio PDFd-fbuser-49417072No ratings yet

- Donation CasesDocument6 pagesDonation CasessalpanditaNo ratings yet

- Argente Vs West Coast Life Insurance Co., 51 Phil. 725, March 19, 1928Document8 pagesArgente Vs West Coast Life Insurance Co., 51 Phil. 725, March 19, 1928BREL GOSIMATNo ratings yet

- Portugal v. AustraliaDocument3 pagesPortugal v. AustraliaStradivarium100% (1)

- Perez v. GutierrezDocument2 pagesPerez v. GutierrezStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Merritt-Chapman & Scott Corp. v. New York Trust Co. stock dividend case digestDocument3 pagesMerritt-Chapman & Scott Corp. v. New York Trust Co. stock dividend case digestStradivariumNo ratings yet

- (Tax 1) (Mactan Cebu v. Marcos)Document3 pages(Tax 1) (Mactan Cebu v. Marcos)StradivariumNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Laws Sample For Legal BibliographyDocument8 pagesMemorandum of Laws Sample For Legal BibliographyStradivariumNo ratings yet

- (Tax2) (CIR v. CA)Document4 pages(Tax2) (CIR v. CA)StradivariumNo ratings yet

- LABOR II | B2015 SUMMARY: Carpo v Chua usury caseDocument3 pagesLABOR II | B2015 SUMMARY: Carpo v Chua usury caseStradivarium0% (1)

- Digest For Magsaysay v. AganDocument3 pagesDigest For Magsaysay v. AganStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Olympia V RazonDocument2 pagesOlympia V RazonStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Tax Report Summaries and Doctrines VDocument2 pagesTax Report Summaries and Doctrines VStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Dividend Declaration Creates Debt Against CorporationDocument2 pagesDividend Declaration Creates Debt Against CorporationStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Hottenstein Et Al. v. York Ice Machinery Corp.Document3 pagesHottenstein Et Al. v. York Ice Machinery Corp.StradivariumNo ratings yet

- Sps. Belen v. Hon. ChavezDocument4 pagesSps. Belen v. Hon. ChavezStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Eritrea v. YemenDocument8 pagesEritrea v. YemenStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Rivera v. Unilab: Labor - B2015 CasesDocument6 pagesRivera v. Unilab: Labor - B2015 CasesStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Local Government | B2015 Case DigestsDocument3 pagesLocal Government | B2015 Case DigestsStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Seguritan V PeopleDocument3 pagesSeguritan V PeopleStradivariumNo ratings yet

- COA v. HinampasDocument4 pagesCOA v. HinampasStradivariumNo ratings yet

- EVIDENCE | B2015 CASE DIGESTSDocument4 pagesEVIDENCE | B2015 CASE DIGESTSStradivariumNo ratings yet

- EVIDENCE | B2015 Jison v. C.A. Case DigestDocument8 pagesEVIDENCE | B2015 Jison v. C.A. Case DigestStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Digest For Magsaysay v. AganDocument3 pagesDigest For Magsaysay v. AganStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Camacho-Reyes v. ReyesDocument8 pagesCamacho-Reyes v. ReyesStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Compiled NIRC ProvisionsDocument13 pagesCompiled NIRC ProvisionsStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Summary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Document4 pagesSummary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Stradivarium0% (1)

- (Planters Products v. CADocument4 pages(Planters Products v. CAStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law 1 Selected JurisprudenceDocument7 pagesTaxation Law 1 Selected JurisprudenceStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Summary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Document4 pagesSummary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Stradivarium0% (1)

- Summary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Document4 pagesSummary of Belgium's War Crimes Statute (Ratner)Stradivarium0% (1)

- Taxation Law 1 Selected JurisprudenceDocument7 pagesTaxation Law 1 Selected JurisprudenceStradivariumNo ratings yet

- Buying and Selling: and Net Profit/LossDocument19 pagesBuying and Selling: and Net Profit/LossMarc Graham NacuaNo ratings yet

- 3 Analysis of Foreign Financial StatementsDocument32 pages3 Analysis of Foreign Financial StatementsMeselech Girma100% (1)

- LOP CalculationDocument5 pagesLOP Calculationpradeeprajendran1988No ratings yet

- Indian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement: Do Not Send This Acknowledgement To CPC, BengaluruDocument1 pageIndian Income Tax Return Acknowledgement: Do Not Send This Acknowledgement To CPC, BengaluruggNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was Shared Via: de La Salle LipaDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was Shared Via: de La Salle LipaAngel ObligacionNo ratings yet

- BUSS 517 Managerial Economics Lecture 3 Group PresentationDocument25 pagesBUSS 517 Managerial Economics Lecture 3 Group PresentationHarish HarishNo ratings yet

- Certain Government Payments: Copy B For RecipientDocument2 pagesCertain Government Payments: Copy B For RecipientDylan Bizier-Conley100% (1)

- Engineering EconomicsDocument40 pagesEngineering EconomicsManoj GautamNo ratings yet

- FinePlanner WorksheetDocument132 pagesFinePlanner Worksheetafifah allias0% (1)

- Acc 211 MidtermDocument8 pagesAcc 211 MidtermRinaldi Sinaga100% (2)

- Form ST-105: Indiana Department of RevenueDocument2 pagesForm ST-105: Indiana Department of RevenueRenn DallahNo ratings yet

- Ferrari Company Presentation: Strategic AnalysisDocument25 pagesFerrari Company Presentation: Strategic AnalysisEmanuele BoreanNo ratings yet

- Tiffany and CoDocument2 pagesTiffany and Comitesh_ojha0% (2)

- Angelwood Development Phase II - 2009 VADocument298 pagesAngelwood Development Phase II - 2009 VADavid LayfieldNo ratings yet

- Director Finance Controller in Boston MA Resume Gregory MurphyDocument2 pagesDirector Finance Controller in Boston MA Resume Gregory MurphyGregoryMurphyNo ratings yet

- System LimitedDocument11 pagesSystem LimitedNabeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- Group 10 VivendiDocument18 pagesGroup 10 Vivendipkm84uch100% (1)

- 2019 Ncaa Eada Report Kent StateDocument80 pages2019 Ncaa Eada Report Kent StateMatt BrownNo ratings yet

- Estate of W. R. Olsen, Deceased, Kenneth M. Owen and First National Bank of Minneapolis, Co-Executors, and Hazel D. Olsen v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 302 F.2d 671, 1st Cir. (1962)Document6 pagesEstate of W. R. Olsen, Deceased, Kenneth M. Owen and First National Bank of Minneapolis, Co-Executors, and Hazel D. Olsen v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 302 F.2d 671, 1st Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Pointers for Finals TAX 301Document4 pagesIncome Tax Pointers for Finals TAX 301Jana RamosNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Science and TechnologyDocument14 pagesFaculty of Science and TechnologyLechumy Pariyasamay100% (1)

- A Case Study of Reebok Acquisition by AdidasDocument4 pagesA Case Study of Reebok Acquisition by AdidasIrtaza Zaidi0% (1)

- A Project Report On Direct TaxDocument44 pagesA Project Report On Direct Taxrani26oct100% (2)

- Equity Resurch ReportDocument10 pagesEquity Resurch ReportZatch Series UnlimitedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Handout Solution - Accounting 405-1Document5 pagesChapter 7 Handout Solution - Accounting 405-1Bridget ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Bunin Business Planning For Financing For Linkedin 10-12-12 Show 97-2003 No PWDocument43 pagesBunin Business Planning For Financing For Linkedin 10-12-12 Show 97-2003 No PWJeffrey H. BuninNo ratings yet

- SPCC Accounts Term 2 HomeworkDocument2 pagesSPCC Accounts Term 2 HomeworkHarsh MishraNo ratings yet

- Plant Business PlanDocument9 pagesPlant Business PlanramsekherNo ratings yet

- Eco-Elasticity of DD & SPDocument20 pagesEco-Elasticity of DD & SPSandhyaAravindakshanNo ratings yet

- Unincorporated Business TrustDocument9 pagesUnincorporated Business TrustSpencerRyanOneal98% (42)