Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Elliot Lake Judicial Inquiry Report (Part Two)

Uploaded by

CityNewsTorontoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Elliot Lake Judicial Inquiry Report (Part Two)

Uploaded by

CityNewsTorontoCopyright:

Available Formats

Report of the Elliot Lake

Commission of Inquiry

Part Two:

The Emergency Response

and Inquiry Process

The Honourable Paul R. Blanger

Commissioner

Report of the Elliot Lake

Commission of Inquiry

Part Two:

The Emergency Response

and Inquiry Process

The Honourable Paul R. Blanger

Commissioner

The Report consists of three volumes:

1. The Events Leading to the Collapse of the Algo Centre Mall;

2. The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process; and

3. Executive Summary.

Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General

ISBN 978-1-4606-4558-1 (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-4606-4556-7 (PDF two volume set)

ISBN 978-1-4606-4555-0 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-4606-4553-6 (Print two volume set)

Queens Printer for Ontario, 2014

Disponible en franais

Recycled

paper

This volume is dedicated to all rst responders

those who put their life and health in harms way

to help others. They are our heroes.

True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is

not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the

urge to serve others at whatever cost.

Arthur Ashe

The Emergency Response

and Inquiry Process

PART

Chapter 1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management . . . . . . . . . . 5

Chapter 3 First Responders and Deployments of Various Teams

(Collapse to 11 p.m. on June 23) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Chapter 4 Rescue Eforts (12:30 a.m. on June 24 to 9:30 a.m. on June 25) . . . .109

Chapter 5 Calling of the Rescue: Now Recovery

(9:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. on June 25) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .163

Chapter 6 Political Intervention and Resumption of the Rescue / Recovery

(7:30 p.m. on June 25 to 6:00 a.m. on June 27) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .207

Chapter 7 Victim Recovery on June 27 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .287

Chapter 8 The Victims: Cause and Time of Death . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .297

Chapter 9 After-Action Reports, Debriefngs, and Lessons Learned . . . . . . . . . .323

Chapter 10 General Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .369

Chapter 11 Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .385

Inquiry Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .435

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

vi

APPENDICES

PART TWO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 475

Appendix A Key people in the emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 478

Appendix B Chronology of the emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 482

Appendix C Schedule of witnesses Part Two . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 485

Appendix D Policy roundtables Part Two . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 487

Appendix E List of appearances for Participants with standing and witnesses Part Two . . . . . . . 495

INQUIRY PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496

Appendix F Order in Council . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496

Appendix G Order in Council extension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 499

Appendix H Commission personnel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 500

Appendix I Inquiry statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 502

Appendix J Letters and statements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 503

Appendix K Commission Rules and Procedural Orders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 521

Appendix L List of overview reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 544

Appendix M Rulings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 545

Appendix N Example of summons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 624

Appendix O Undertaking re confdentiality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 627

Appendix P Certifcate of production . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 633

Appendix Q Example of Section 17 Notice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 635

Appendix R Letter to Attorney General requesting extension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 637

GLOSSARY, ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 641

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 643

Abbreviations and Acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 647

CHAPTER

Introduction

Before, you are wise; after, you are wise. In between you are otherwise.

David Zindell, The Broken God

u

It is easy to be wise after the event.

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Sherlock Holmes

u

This second volume of the Report examines the emergency response in the aftermath of the Algo Mall collapse.

Unlike Part One, which reviewed a span of more than 30 years, these chapters set out a story of less than a

week in duration. Compared to the behaviour of many of the players whose three-decade-long involvement in

the Malls well-being may be questioned and criticized, the emergency response cannot be faulted for lack of

praiseworthy intentions, engagement, determination, and, not infrequently, bravery and courage.

During this response, a congruence of errors some minor, some more important led to a rescue efort that

was no model of perfection. As a result, questions will long persist about the possibility that Lucie Aylwin could

have been rescued. As I pointed out elsewhere in this Report, we learn best through experience. A critical analysis

of that experience is crucial to identify error or to confrm success. The lessons learned can then be transmitted to

others to improve future responses.

In this part of the Report, I will attempt a detailed narrative of the events that followed the collapse on

June 23, 2012. Inevitably, given the varying quality of observation in times of stress, there will be diferent

interpretations of discrete events. That is the nature of human memory, particularly when it is unaided by

contemporaneous recording and prompt, careful debriefng.

Doloris Perizzolos death was unquestionably and mercifully quick. But the extent to which miscues,

miscommunications, and mistakes prevented the rescue of Lucie Aylwin is a difcult question. Some medical

evidence supports the proposition that death came quickly. However, living for a period of time was not

inconsistent with any of the medical indicia discussed by one medical witness. Tantalizing signs may lead one to

conclude that it is probable (though by no means certain) that she lived for some time after the initial collapse

and might have been found alive had the rescue efort been executed more rapidly and efectively. By 5 a.m. on

June 25, however, it is probable (but again, not conclusively certain) that she had died. We will never confdently

know the answer to these troubling concerns.

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

2

The hearings for this part of the Inquiry lasted 36 days, and I heard 52 witnesses. Many of those witnesses, family

members and loved ones in particular, recounted being desperate for information and decried the quality and

manner in which it was communicated to them.

I heard from frst responders who worked to exhaustion, yet resisted and resented being ordered to stop. I heard

from community and frst-response leaders who were well-meaning, but often appeared confused about their

roles and responsibilities.

I heard from the provinces premier, Dalton McGuinty, whose concern and support throughout the ordeal was

genuine and constant. He gave hope and renewed determination when the rescue efort had ebbed to its lowest

point. I also heard from the regions MPP (Algoma-Manitoulin), Michael Mantha, whose presence, assistance, and

moral support to the community was unfagging and tireless and who represented the best of what is expected

of our elected representatives.

My analysis of the facts underpinning this narrative follows, along with my recommendations to improve

emergency responses. I also describe the process of this Inquiry and make suggestions for future such

commissions. Improvement is achieved gradually and incrementally and builds on the shoulders of others.

Perfection is an impossibly elusive goal one that is virtually never achieved. As Vince Lombardi is quoted

assaying, Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.

I embark on that analysis with difdence and some signifcant reservation, because I am aware of this

Commissions lack of expertise in emergency rescue operations. The training and practical experience of many of

the frst responders was decades long. My learning period, as well as that of Commission counsel, has been brief

and purely theoretical.

I am also conscious, as I previously commented, of the perils of judging events in hindsight. Choosing the right

path through the thicket is easy when you can look down on it from a high vantage point, but not when you

are enmeshed in it on perilous ground. Although hindsight is a dangerous tool in assessing past conduct, it is,

however, essential in crafting recommendations. Many witnesses, experts in their own right, commented in their

testimony on what they and others should have done diferently. Their views are important and valuable, and, in

crafting my recommendations, I gave a lot of weight to their opinions.

Unfortunately, the rescue efort that was mounted after the collapse did not save any lives. The measure of a

responses efectiveness cannot simply be gauged by whether lives were saved as a result of it. That measure

is far too simplistic. An inept rescue may save lives by pure luck or cause the further loss of life; by contrast,

circumstances may defeat the best-executed plans.

One constant, however, stands out above all the others: an efective and efcient frst-response system is

essential to the health, safety, and security of Ontarios citizens. With the integration of Ontarios frst-response

organizations with those of other provinces, this system is now also essential for all Canadians. Any diminution

in the fnancial contributions of governments municipal, provincial, or federal is unwarranted and dangerous.

Quite the opposite: those contributions should be enhanced.

The evidence I heard in the second phase of the Inquiry provided me with a view into the world of emergency

management and response. This world, I have come to learn, is heavily populated by totally committed, selfess,

and courageous men and women. That said, it still remains that few human endeavours cannot be improved

upon. Any criticism I make about any aspect of the response to the Algo Mall collapse should not be interpreted

as a lessening of my esteem and admiration for our frst responders.

Chapter 1 Introduction

3

Stated in their simplest terms, my principal conclusions for this part of the Inquiry are as follows:

Doloris Perizzolos death was nearly instantaneous after the collapse, but it is probable (though by no

means certain) that Lucie Aylwin survived under the rubble for a period of up to 39 hours. It is unlikely that

she survived beyond 5 a.m. on June 25. There exists a possibility she might have been rescued, but we will

never know for sure.

Local authorities acted promptly and appropriately in the immediate aftermath of the collapse. They

assisted in the evacuation of the Mall, helped the injured, and secured the site by shutting of utilities and

establishing site control. Provincial authorities were rapidly informed, and assistance was summoned after

the declaration of a municipal emergency.

HUSAR/TF3 could have deployed more rapidly. UCRTs deployment speed was exceptional.

Both HUSAR/TF3 and UCRT deployment numbers were not optimal, particularly at the command level.

The lack of an incident action plan was detrimental to the rescue efort.

The Incident Management System was improperly applied: no one understood or respected its mandated

command structure.

The relationship between HUSAR/TF3 and UCRT was occasionally problematic.

There was a failure to resort to crane / rigging operations early and consistently they were relegated to a

solution of last resort.

Record-keeping and note-taking were defcient.

Communications among responders, with victims families, and with the media and the general

public were poor.

Although it was proper to remove the rescuers from the building because of the dangerous state of the

rubble pile, the rescue was called of, instead of being paused while alternatives were considered.

The services ofered by Ontario Mine Rescue should not have been ignored.

The role of Ministry of Labour ofcials was widely misunderstood.

After-action debriefngs and many after-action reports were either non-existent or poorly done.

Provincial legislation, including the Coroners Act, does not allow an ofcial to demolish a building to

retrieve a body.

The premier of Ontario, his ofce, and other provincial authorities acted with leadership, genuine

compassion, and assistance when hope seemed lost.

Ontarios urban search and rescue system needs a careful re-examination to provide better overall coverage

and quality of service.

One fnal comment: I was informed during the hearings that Fire Chief Paul Ofcers nomination of certain of

his Elliot Lake frefghters for the Ontario Medal for Firefghter Bravery Award have been put on hold until this

Commission has completed its work. These awards should wait no longer. They are richly deserved.

CHAPTER

Background of Responders

and Emergency Management

Emergency management in Ontario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Graduated problem solving and emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

The role of the municipality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

The municipal emergency management program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Municipal emergency control groups . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Municipal emergency management program coordinator and committee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Declaration of an emergency by the municipality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Community emergency operations centres . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Mutual aid system and municipal capacity expectations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Volunteers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

The role of the province . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Premier of Ontario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Lieutenant governor in council . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Provincial Emergency Response Plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

The Provincial Emergency Response Plan for Building Structural Collapse 2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Provincial Emergency Operations Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Emergency Management Ontario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Ofce of the Fire Marshal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Mutual assistance between provinces and territories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

The role of the federal government . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Incident Management System: the system as it is intended towork . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Background and purpose of the Incident Management System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

The Incident Management System is not mandatory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Incident Management System organizational structure and management functions . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

The incident commander . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Operations, planning, logistics, and fnance and administration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

6

The incident action plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Planning cycle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Training . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Overview of key players in the Elliot Lake response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Elliot Lake Fire Department . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Training and equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Tactical priorities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

City of Elliot Lake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Emergency response plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Community Control Group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Responsibilities of some of the key players of the Community Control Group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Emergency Operations Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

East Algoma OPP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

City of Toronto Heavy Urban Search and Rescue team . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Classifcation of Urban Search and Rescue teams . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

History of the Toronto HUSAR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Composition of the Toronto HUSAR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Training standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Team member training . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Mobilization of HUSAR/TF3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Ontario Provincial Police . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Composition of UCRT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Training of UCRT members . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Deployment of UCRT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

The Ministry of Labour in an emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Why the Ministry of Labour may get involved in an emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

The applicability of the Occupational Health and Safety Act at the scene of an emergency response . . . . . . 36

The expected roles of Ministry of Labour personnel at an emergency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Ontario Mine Rescue a successful emergency response organization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Safety of responders is the frst priority . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Extensive training and equipment, similar to that of HUSAR/TF3 and UCRT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Response time: on site within 30 minutes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Chain of command . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

One ofcial in charge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Support and information from the mine rescue ofcer and the emergency control group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Briefng ofcer as the liaison between the control group and the operations team . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Team captain in charge of operations team . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

7

Planning is absolutely critical . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Briefng team members: in writing, with opportunity for questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Written logs and reports required . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Debriefngs: essential and useful . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

OMRs experience: extensive and useful . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

8

To understand the response to the collapse of the Algo Mall, it is necessary to frst review the way the province,

the municipalities, and other responders are organized to deal with emergencies of this type. Accordingly, I will

provide background information in this chapter on

emergency management in Ontario;

the Incident Management System;

organizations that participated directly in the rescue; and

organizations that provided support and advice.

The description of the emergency management structure in Ontario that follows refects the one in place at

the time of the Malls collapse. Although there have been some administrative changes since then, it is my

understanding that the framework remains essentially the same.

Emergency management in Ontario

The primary provincial legislation dealing with emergency management is the Emergency Management and Civil

Protection Act (EMCPA). It refects the fve pillars of emergency management:

mitigation

prevention

preparation

response

recovery

1

The Act defnes emergency as a situation or an impending situation that constitutes a danger of major

proportions that could result in serious harm to persons or substantial damage to property and that is caused by

the forces of nature, a disease or other health risk, an accident or an act whether intentional or otherwise.

2

Graduated problem solving and emergency response

The frst response is almost always local: it begins with the individual or the

family and evolves from there. The provinces emergency response regime is

designed to refect this process. The Ontario governments Provincial Emergency

Response Plan expects individuals and families to be able to respond to

an emergency and be self-sufcient for the frst 72 hours.

3

This approach is

described as graduated problem-solving.

4

It is bottom up and meant to keep

emergency response as localized as possible while ensuring that all the necessary

resources are available in a timely fashion.

Where an emergency escalates beyond the capacities of the individual or family,

the expectation is that the local community or municipality will take over.

Communities assist as a matter of routine through emergency responders such

aspolice, fre, and emergency medical services.

5

Where an emergency

escalates beyond the

capacities of the individual

or family, the expectation

is that the local community

or municipality will take

over. Communities assist as

a matter of routine through

emergency responders

such as police, fre, and

emergency medical services.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

9

Where the emergency in question overwhelms the capacities of the local municipality or community and its

frst responders, the next step is to seek mutual aid or assistance from neighbouring services, municipalities, and

communities or from the local county or region. Mutual aid programs are unique to fre services and are required

under the Fire Protection and Prevention Act.

6

Municipalities can also form agreements with neighbouring

communities to provide assistance to each other in times of need for matters that are not related to fres. These

agreements are called mutual assistance.

7

Where the mutual aid or assistance system will not sufce, the local community

can look to the Ontario government for further support. The Province of

Ontario has emergency resources and expertise which may be used to deal

with emergency response needs that are beyond the capabilities of local

communities.

8

Indeed, the local community can ask for provincial assistance at

any time, even where the mutual aid or mutual assistance systems are sufcient.

9

Finally, and depending on the nature and severity of the incident in question,

the province may require the assistance of the federal government or even

international assistance. The nature of the emergency may also be such that

jurisdiction falls automatically to the federal government.

10

The provision of assistance from one level of government to another may require a declaration of emergency,

unless normal powers and procedures will sufce. A declaration of emergency, in keeping with the graduated

approach, should be at the lowest level of jurisdiction. As such, it should seldom be necessary to declare a

provincial or federal emergency, even though resources from these jurisdictions will frequently be provided in

support of an emergency declared by a municipality or a First Nation.

11

The role of the municipality

In accordance with the graduated problem-solving model, emergency response in Ontario is to be managed at

the lowest level possible at the community or municipality level. As such, Ontario municipalities are subject

to a series of legislated responsibilities related to emergency response, chiefy pursuant to the Emergency

Management and Civil Protection Act. The Act also sets out powers that may be exercised by the municipality and

the province during an actual emergency, but without expressly defning the relationship between the province

and the municipalities.

12

All municipalities must have in place the following structure for emergency response. It includes the creation of

community emergency management programs, emergency plans, control groups, emergency operation centres,

and mutual aid arrangements.

The municipal emergency management program

Every municipality in Ontario is required by law to develop and implement an emergency management program

and to pass a by-law specifcally adopting the program. It must include an emergency response plan, training

programs, and exercise sessions for municipal employees and others as well as the procedures to be followed

in emergency response and recovery activities. It must also provide for public education on the risks to public

safety and on how the public can best be prepared for emergencies.

13

The training programs and exercises for

municipal employees and others allow for the inclusion of non-governmental organizations that are expected to

play a role in the emergency response plan for example, the Salvation Army or the Red Cross.

14

The Province of Ontario has

emergency resources and

expertise which may be used

to deal with emergency

response needs that are

beyond the capabilities of

local communities.

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

10

Dan Hefkey holds the position of commissioner for community safety, as he did when he appeared at the Inquiry.

The fre marshal and the chief of Emergency Management Ontario both report directly to him. He explained that

the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act does not contain any provision dealing with non-compliance

with the Act.

15

Although the Act requires municipalities to have an emergency management program that

includes an emergency plan, there is no statutory penalty for those that do not comply. He testifed, however,

that there is almost complete compliance. At any time, on average, only four to eight municipalities in the

province are defcient in some aspect of the requirements.

16

Municipalities must conduct annual reviews of their emergency management programs and make

recommendations to the local council about any revisions that are required.

17

The emergency management

program must also assess various hazards and risks to public safety in the community which could give rise

to emergencies and, in addition, identify facilities and infrastructure that are at risk of being afected by

emergencies and for which the municipality is responsible.

18

This process of hazard identifcation and risk assessment is expected to shape the plan. It identifes what the

hazards are within the municipality and makes a judgment on the likelihood of an event happening as well as its

consequences in terms of lives and property damage. Emergency Management Ontario, a branch of the Ministry

of Community Safety and Correctional Services which is responsible for developing, promoting, and maintaining

emergency programs, expects that each municipality will regularly revisit this assessment, simply because

changes in circumstances require changes to emergency plans. Municipalities are not required to provide

Emergency Management Ontario with a copy of their hazard identifcation and risk assessment.

19

The emergency response plan sets out the procedures on how each particular municipality will respond to an

emergency.

20

In addition, it lays out the responsibilities of municipal employees in carrying out the plan.*

Municipal emergency control groups

Municipalities are also required by regulation to have in place a municipal emergency control group to direct

the municipalitys response in an emergency, including the implementation of the emergency response plan.

21

This group is more commonly referred to as the Community Control Group (CCG).

22

Mr. Hefkey explained that the role of the CCG is to act in support of those who are actually dealing with the

emergency. The group does not direct the responders its concern is generally broader than the emergency

incident itself and includes the efects and consequences of the emergency on the community.

23

The group

must be composed of ofcials or employees of the municipality appointed by the municipal council, and it may

include members of the City Council itself. All members of the group must complete annual training as required

by the chief of Emergency Management Ontario.

24

According to Mr. Hefkey, a CCG would typically include the mayor, deputy mayor, chief administrative ofcer, and

the heads of the municipal departments such as public works, police, fre, emergency management services,

public health, and social services.

25

When an emergency occurs, the municipalitys emergency control group

will usually convene to activate the emergency plan and, using that plan, access local resources to support

emergency operations.

26

* Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, O Reg 380/04, s 15.

Further instruction on minimum standards for municipal (and provincial) emergency management programs is found in Ontario Regulation

380/04, created to support the requirements in the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

11

An incident commander may be appointed by the CCG to manage operations at the site of the emergency event.

This commander is usually a senior ofcer from one of the local emergency services.

27

That said, an incident

command structure will likely already have been in place at the onset of the emergency response, set up by the

emergency frst responders even before the declaration of emergency by the community.

Municipal emergency management program coordinator and committee

The municipality must also designate an employee of the municipality or a member of the city council as its

emergency management program coordinator. In addition, it must have in place an Emergency Management

Program Committee (EMPC).

28

The emergency management program coordinator manages the development and implementation of the

municipalitys emergency management program within the municipality and, to the extent possible, coordinates

it with that of other municipalities, ministries of the Ontario government, and organizations outside government

that are involved in emergency management.

29

The EMPC advises the municipal council on the development and

implementation of the municipalitys emergency management program. It also conducts an annual review of the

program and makes recommendations to council for its revisions resulting from an updated hazard identifcation

and risk assessment.

30

Declaration of an emergency by the municipality

Section 4 of the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act provides that the head of the council in a

municipality may declare that an emergency exists in either the whole or a part of the municipality. The council

head will then take such action and make such orders as he or she considers

necessary, and which are not contrary to law, to implement the municipalitys

emergency plan and to protect both the property and the health, safety, and

welfare of the residents in the emergency area.

31

The declaration can be made

whenever the head of council considers that an emergency exists. There is no

condition precedent, or particular event, that must occur before the exercise of

this power.

32

Of course, municipalities can (and do) take steps to respond to an

emergency without making a formal declaration.

33

If a municipality declares an emergency, it must notify the province.

34

On

average, every year some 23 municipal emergency declarations are made in

Ontario. However, no provincial emergency has been declared since the Act came into force in 2006.

35

Community emergency operations centres

During an emergency, municipalities are required to have a community Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) in

place, operating under the direction of the municipal emergency control group.

36

From there the group manages

the emergency. When an emergency situation arises, local municipalities are expected to follow their emergency

plans and, where necessary, activate their EOC in order to coordinate local emergency response eforts.

37

The municipality must appoint an emergency information ofcer to act as its primary media and public contact

during an emergency.

38

That does not mean, however, that the emergency information ofcer has to be the

spokesperson for the municipal emergency control group. It is expected that the designation of a spokesperson

will be addressed within the emergency response plan.

39

If a municipality declares

an emergency, it must notify

the province.

On average,

every year some 23 municipal

emergency declarations are

made in Ontario.

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

12

The municipality should have appropriate technological and telecommunications systems in place to ensure

efective communication in an emergency. It must also have a procedure to inform the Provincial Emergency

Operations Centre (PEOC) of an emergency and of possible requirements for assistance.

40

Mutual aid system and municipal capacity expectations

Within the gradual problem-solving approach, a municipality can rely on provincial mutual aid systems for fre

departments when an emergency exceeds its capacity. The mutual aid system is established under the authority

of the Fire Protection and Prevention Act, 1997, and administered by the Ofce of the Fire Marshal.

Fire coordinators, appointed by the Ofce of the Fire Marshal, are responsible for establishing and maintaining

a mutual aid plan through which the various fre departments serving a designated area agree to assist each

other in the event of an emergency.

41

Fire coordinators submit these mutual

aid plans to the fre marshal for review and approval, and the Ministry of

Community Safety and Correctional Services maintains a repository of all

Ontario mutual aid plans for use in emergency situations.

42

The mutual aid can take the form of providing personnel and/or equipment

to deal with the emergency. It also includes the provision of personnel from

the neighbouring fre service to tend to the ongoing needs for fre protection

services in the host community while the host fre service deals with

the emergency.

43

The Fire Protection and Prevention Act, 1997, requires that municipalities

provide fre protection services to their communities as necessary and

in accordance with their needs and circumstances. Municipalities are

not required to possess more extensive capacities such as urban search

and rescue teams.

44

Volunteers

Ontarios emergency response plan briefy addresses the role of volunteers and supporting organizations

in an emergency response. Municipalities may require personnel, services, equipment, and/or material from

non-proft or voluntary organizations and should include these types of considerations in their emergency

response planning processes.

45

The Provincial Emergency Response Plan makes the following cautionary comment about the use of volunteers

during an emergency:

Municipalities and provincial ministries should carefully consider their need for, and the capabilities

of, unafliated volunteer assistance during an emergency and systematically register all those who

participate in the emergency response.

46

The Fire Protection and

Prevention Act, 1997, requires

that municipalities provide

fre protection services to their

communities as necessary

and in accordance with their

needs and circumstances.

Municipalities are not required

to possess more extensive

capacities such as urban search

and rescue teams.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

13

The role of the province

Where the municipal and local structure is insufcient to deal with an emergency, the municipality can look to

the province for further resources and assistance.

The Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act contains organizational structures, roles, and responsibilities

for all ministries that are analogous to those required of municipalities. For example, ministries must have a

ministry emergency management coordinator and a ministry action group. The groups role and responsibilities

are the same as those of a municipalitys emergency control group.

47

Premier of Ontario

The Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act provides that the premier of Ontario may, if in his or her

opinion the urgency of the situation requires that an order be made immediately, declare that an emergency

exists throughout Ontario or in any part thereof.

48

If the emergency area or any part of it is within the

jurisdiction of a municipality, the premier may, if deemed necessary, direct and control the administration,

facilities, and equipment of the municipality in the emergency area

49

and may direct other municipalities to

render assistance.

50

The premier and the lieutenant governor in council may provide overall direction to the management of an

emergency response when a provincial emergency has been declared, but not where the province has merely

provided provincial resources or assistance to a municipality.

51

Lieutenant governor in council

Powers to declare an emergency are also conferred on the lieutenant governor in council. While the premier

may declare a provincial emergency only if the urgency of the situation requires that such a declaration be made

immediately, the lieutenant governor in council may do so if the resources normally available to the government

are considered insufcient to respond adequately to the crisis.

52

Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services

The key ministry within the Government of Ontario for emergency response is the Ministry of Community

Safety and Correctional Services. It houses important players in the emergency response feld, including

Emergency Management Ontario and the Ofce of the Fire Marshal. In August 2013, these two divisions were

merged to form the Ofce of the Fire Marshal and Emergency Management. According to a government press

release, [t]his new, integrated organization will strengthen the co-ordination and delivery of community

safety programs, without impacting front-line services.

53

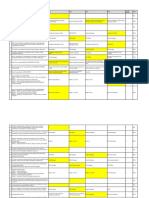

Figure 2.2.1 sets out an organizational chart for the

Community Safety side of the ministry as it existed on June 1, 2012.

If several ministries require a coordinated efort, the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services will

coordinate the joint response, normally through the Provincial Emergency Operations Centre (PEOC) described

below. In addition, the ministry has the primary responsibility for managing the consequences of any structural

collapse of buildings in Ontario.

54

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

14

Figure 2.2.1 Organizational chart of the community safety side of Ministry of Community Safety and

Correctional Services

Source Exhibit 7886

Advisory and Adjudicative Agencies,

Boards & Commissions

Const. Joe MacDonald

Public Safety Ofcers Survivors Scholarship

Fund Chair

Fire Safety Commission Chair

Animal Care Review Board Chair

Fire Marshals Public Fire Safety Council Chair

Ontario Police Arbitration Commission Chair

Ontario Civilan Police Commission Chair

Ontario Parole Board Chair

Death Investigation Oversight Council

Minister of Community

Safety and Correctional

Services

Deputy Minister

Community Safety

Executive Assistant

Project

Management

A. Director

Operational

Services

Director

Prov. Command

Field Operations

Dep. Comm.

Prov. Command

Investigations/

Organized Crime

Dep. Comm.

Prov. Command

Trafc Safety &

Ops. Support

Dep. Comm.

Commissioner,

Community Safety

Commissioner

Ofce of the Chief

Coroner

Chief Coroner

Ontario Forensic

Pathology Service

Chief Forensic Pathologist

Ofce of the Fire

Marshal

Fire Marshal

Emergency

Management Ontario

ADM/Chief

External Relations

Director

Private Security &

Investigative Services

Director

Ontario Police College

A. Director

Centre of Forensic

Sciences

Director

Criminal Intelligence

Service Ontario

Director

Ontario

Provincial Police

Commissioner

Public Safety

ADM

Deputy Fire Marshal

A. Dep. Fire Marshal

Administration and

Business Services

A. Director

Support Programs

Director

Bureau Commander

Business &

Financial Planning

Director

Bureau Commander

Career

Development

Chief Superintendent

Prov. Command

Corporate

Services

Prov. Comm.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

15

Provincial Emergency Response Plan

The Ontario government is responsible for protecting public health and safety, property, and the environment

within its borders. It has primary responsibility for managing the consequences of an emergency, such as a

buildings structural collapse or a chemical spill, once the community or the municipality has exceeded its

resources, and for implementing mutual aid agreements. The Provincial Emergency Response Plan, developed

pursuant to the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, is used to coordinate the overall provincial

emergency response. It outlines how Emergency Management Ontario and the ministries respond to widespread

or large-scale emergencies.

55

The stated purpose of the Provincial Emergency Response Plan is to establish a framework for a systematic,

coordinated and efective emergency response by the Province of Ontario to safeguard the health, safety,

welfare and property of its citizens, as well as to protect the environment and economy of the area afected by an

emergency, excluding nuclear emergencies.

56

The Act requires the lieutenant governor in council to formulate a

distinct emergency plan respecting emergencies arising in connection with nuclear facilities.

57

The Provincial Emergency Response Plan for Building Structural Collapse 2010

All ministries of the provincial government are required to develop an emergency management program that

includes an emergency plan. All ministers must develop an emergency plan for any emergency that afects the

continuity of operations and services in their respective ministries. In addition, 13 ministers have been given

the responsibility to develop emergency plans with respect to specifc types of emergencies set out in Order

in Council 1157-2009. These plans, developed by the ministries, ft within the overall Provincial Emergency

Response Plan.

58

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services was given responsibility to develop

the emergency response plan for the structural collapse of buildings.

59

The Provincial Emergency Response Plan for Building Structural Collapse 2010 recognizes that the primary

responsibility for managing an emergency resulting from a buildings structural collapse rests with the

community and with local resources. The plan addresses how the province is intended to respond to such an

emergency. It does not require the declaration of a provincial emergency to become operational. In fact, it does

not specifcally require the declaration of a municipal emergency. Since the community has responsibility for

managing the emergency, the province has a supporting role by providing assistance. This assistance may take

the form of simply providing advice, but it may also expand to the provision of personnel, equipment, and other

resources to assist the community in dealing with the cause of the emergency.

60

The province, through the Ofce of the Fire Marshal, has access to a number of specialized teams that can

assist in the response to a building collapse urban search and rescue teams as well as chemical, biological,

radiological, nuclear, and explosive teams. Nearly all these teams are operated by municipalities. The province

has entered into a memorandum of understanding with all the municipalities which allows it to deploy these

teams under specifed circumstances.

61

When provincial resources are sent to support a local municipality, they

come under the operational control of the local incident commander in accordance with the provincial Incident

Management System (IMS) doctrine described later.

62

In the event of a buildings structural collapse, the province has access to two urban search and rescue teams.

The frst, known as Canada Task Force 3 (TF3), or Toronto HUSAR, is a heavy-level urban search and rescue team

operated by the City of Toronto.

63

The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) has an urban search and rescue team as well

as a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRNE) team that is collectively known as UCRT.

64

The UCRT team is available to the province on request as long as it is not otherwise occupied.

65

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

16

The OPP team is located in Bolton, Ontario, a few kilometres north of Toronto. Therefore, the provinces

entire inventory of urban search and rescue assets is located in the Greater Toronto Area. The cities of Ottawa

and Thunder Bay each operate their own medium-level search and rescue team.* The province has not

signed a memorandum of understanding with either city, and, therefore, these teams are not deployable

by the province.

66

Municipalities in Ontario operate nine CBRNE teams in all. The cities of Toronto, Ottawa, and Windsor have

level 3teams,

and the cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay, Cornwall, Peterborough, North Bay, and Kitchener /

Cambridge / Waterloo have level 2 teams.

67

The cost of deployment by the province of any of the specialized teams, whether urban search and rescue or

CBRNE, is borne by the province, not the municipality.

68

Provincial Emergency Operations Centre

The Provincial Emergency Operations Centre (PEOC) is located within the Ministry of Community Safety and

Correctional Services in Toronto and is managed by Emergency Management Ontario. It is stafed at all times.

69

Ontarios Provincial Emergency Response Plan calls for potential or actual emergencies to be reported promptly

to the centre. These reports may come from many sources, including municipalities or other ministries.

70

Ontario has provided a description of how Emergency Management Ontario (EMO) and the PEOC respond

to an emergency declaration:

When a Head of Council declares an emergency, the province must be notifed. Typically a municipality

will notify the province via a telephone call/fax to the 24/7 Duty Ofce in the Provincial Emergency

Operations Centre (PEOC).

When the PEOC Duty Ofcer receives a declaration of an emergency, a series of questions are posed

to the person notifying the PEOC to verify contact information, situational details and to determine

if any provincial assistance is being requested by the municipality. If provincial assistance is required,

the PEOC Duty Ofcer will notify the applicable provincial ofcials regarding the request and the

circumstances thereof.

During normal business hours, Emergency Management Ontario staf in the PEOC and EMOs Operations

Section will lead EMOs response to the emergency declaration. This will include creating an Emergency

Information Notifcation (EIN) [replaced after May 2013 by an Incident Briefng Form], disseminating this

document to designated provincial and ministry representatives, contacting ministry representatives

who may be able to support response operations and scheduling a teleconference with impacted

municipalities, ministry ofcials and, as necessary[,] federal departments and agencies.

Outside of normal business hours, this work follows a similar path, but is truncated due to fewer staf

being readily available. The PEOC Duty Ofcer is in regular contact with an EMO Duty Operations Chief

(DOC) and Duty Commander (DC) and these three ofcials would work collaboratively to create the

necessary EINs and notify provincial staf of the emerging situation.

71

When a municipality declares an emergency, all the various ministry emergency management coordinators are

notifed by the PEOC. A ministry may choose to send staf to the event if it has implications for its mandate.

72

* Urban search and rescue teams are classifed as heavy, medium, or light, based in part on their capacity to operate. These distinctions

will be explained in greater detail later on in this Report.

These levels refer to National Fire Protection Standard 472, which covers minimum competencies of persons responding to incidents

involving hazardous materials. Level 3 refers to the technician level, whereas level 2 to operational level. Further details are explained

later in the Report.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

17

Emergency Management Ontario

Emergency Management Ontario (EMO) is the organization within the Ministry of Community Safety and

Correctional Services with the responsibility to monitor, coordinate, and assist with the promotion, development,

implementation, and maintenance of emergency management programs in Ontario at both the municipal and

the provincial ministry levels. This responsibility includes the coordination of these programs with the federal

government. In fulflling this special coordination role, EMO coordinates provincial emergency response through

the PEOC when required and provides advice and assistance to communities and ministries in all areas of

emergency management. This assistance includes regular contact with municipalities to assess their compliance

with the requirements of their particular emergency management program.

73

EMO also maintains the Provincial Emergency Response Plan and the Provincial Nuclear Emergency Response

Plan. The Provincial Emergency Response Plan must be fully reviewed, amended, and brought forward for

ministerial approval at least once every four years.

74

As discussed, EMO has also developed an emergency

response plan specifcally for structural collapses the Provincial Emergency Response Plan for Building Structural

Collapse 2010.

75

The Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act provides for the appointment of a chief of EMO, who, under

the direction of the minister of community safety and correctional services, is to be responsible for monitoring,

coordinating and assisting in the development and implementation of municipal and provincial emergency

management programs throughout Ontario.

76

EMO has feld ofcers throughout the province who live and work in the geographical area they serve. They

can ofer subject matter expertise, support, and advice to the community emergency management program

coordinators located within their respective areas.

77

During an emergency, whether declared or not, an EMO representative may be deployed to a community to

act as a liaison and to provide emergency management advice to council and senior staf. Other provincial staf

may be deployed to provide additional advice, assistance, and services, under the coordination of EMO.

78

Such

deployed staf are referred to by the Government of Ontario as the EMO Provincial Emergency Response Team

(PERT), primarily made up of EMO feld ofcers.

79

EMO also has training available for all emergency management personnel in Ontario (including provincial and

local emergency management personnel and frst responders). Some of the courses available are as follows:

80

Basic Emergency Management Course, which covers all the basic principles of emergency management.

Basic Emergency Management Instructor Course, which enables the candidate to be a certifed basic

emergency management instructor.

Community Emergency Management Coordinators Course, which provides specifc training to enable the

designated community emergency management coordinator to administer the municipalitys emergency

management program.

Incident Management System (IMS) courses, which provide a progressive learning system to train

emergency responders in how to perform specifc emergency management functions on a coordinated

basis during emergency operations. Five IMS courses were available in Ontario at the time of the

Commission hearings.

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

18

Ofce of the Fire Marshal

The Ofce of the Fire Marshal, along with the Ontario Provincial Police and Emergency Management Ontario feld

ofcers, may be one of the frst provincial-level actors involved with emergency response at the local level, either

monitoring or responding directly to the emergency.

As mentioned earlier, the fre marshal is responsible for appointing fre coordinators for designated areas.

These, in turn, establish and maintain mutual aid plans under which the fre departments that serve a

designated area agree to assist each other in the event of an emergency and to perform other duties the fre

marshal may assign.

81

In addition to overseeing the implementation of mutual aid plans, the Ofce of the Fire Marshal has an

Emergency Preparedness and Response Unit. This unit is designed to deal with situations where individual

fre departments need to respond to incidents beyond their capabilities and beyond the capabilities of the

mutual aid system.

82

The unit responds on a full-time (24/7) basis to requests for assistance from municipal fre departments,

including heavy urban search and rescue. Personnel in the Ofce of the Fire Marshal assess the need of a

particular situation to ensure that the appropriate resource is deployed. In addition, program specialists

from the unit are available to be deployed principally for liaison and for supporting the operations.

83

Carol-Lynn Chambers was the operations manager of the Emergency Preparedness and Response Unit at

the Ofce of the Fire Marshal at the time of the collapse. She explained that, typically, a local fre chief would

contact the Provincial Emergency Operations Centre, which in turn would contact the operations manager.

She would then get the phone number of the fre chief and call the chief directly to discuss what was needed,

activate the appropriate response, and, if desirable, allocate any of her staf. She would then advise the Provincial

Emergency Operations Centre of the appropriate response, which in turn would advise the commissioner of

community safety.

84

Other resources available through the Ofce of the Fire Marshal include

advice, technical assistance, and equipment for hazardous material emergencies; and

support for other major emergencies, in various forms, including portable lighting and generator support,

radio / communications equipment, and incident documentation.

85

Finally, the Ofce of the Fire Marshal can be involved with the operation and deployment of the Toronto Heavy

Urban Search and Rescue team, as discussed further below.

86

Mutual assistance between provinces and territories

There are also mutual assistance agreements between the provinces and territories in Canada. A Memorandum

of Understanding on Jurisdictional Emergency Management Assistance has been approved by all provinces and

territorial ministers responsible for emergency management. This memorandum provides the framework within

which provinces and territories would provide support to other Canadian jurisdictions.

87

Heavy urban search and rescue teams are located in Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, and Brandon, Manitoba.

88

If a

province needed the assistance of any of these teams, a province-to-province request would be made under this

memorandum of understanding. The expectation is that the team will be deployed if it is available.

89

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

19

The role of the federal government

If an emergency requires support or resources beyond what a municipality or the province is capable of

providing, the province can make a formal request for assistance from the federal government. Municipalities

may not apply directly for federal emergency assistance, which would include assistance from the military.

90

The federal government intervenes in an emergency in a province only when requested to do so by provincial

emergency management organizations or when an emergency clearly will have an impact on areas of federal

jurisdiction

91

such as emergencies created by acts of terrorism.

92

Incident Management System: the system as it is intended

to work

The Incident Management System (IMS) is a doctrine sponsored by the Government of Ontario which is intended

to provide a single, province-wide system for emergency management and to be used by the various response

organizations in the province. In this section of the Report, I describe in summary form how IMS is intended

to operate. I will not, at this time, comment either on its efcacy or the extent to which it was followed in the

response to the collapse of the Algo Mall. That analysis will come later in the Report.

Background and purpose of the Incident Management System

The Government of Ontario developed the IMS doctrine in an attempt to coordinate emergency management

among the afected community and the related organizations, institutions, and industries. The stated objective is

to provide a fexible, scalable and consistent IMS structure and process for all levels of government, emergency

response organizations, communities, ministries, NGOs and the private sector.

93

The IMS was sponsored by Emergency Management Ontario and developed by a steering committee and several

working groups made up of representatives from organizations involved in emergency response, including fre

services, police services, and governmental departments. Their work produced the IMS doctrine, a 140-page

document in which the system is described. The IMS doctrine was ultimately approved on January 30, 2009, by

the Ontario government.

94

The impetus for developing this doctrine arose following the terrorist attacks in New York City, Pennsylvania,

and Washington, DC, in September 2001. In the wake of that event, as well as other more recent emergencies

including the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) pandemic, the provincial government struck

a commission to review Ontarios emergency response capabilities and to make recommendations for

improvement.

95

The commission noted that the response to SARS, which was principally a health emergency,

involved many diferent disciplines, including police and fre services. In view of the myriad organizations that

can be called upon to respond to an emergency in Ontario, the commission recommended that a common

protocol system be put in place so that the management of an emergency involving diferent response

organizations could be coordinated more easily.

96

The IMS doctrine was originally premised on a similar emergency response regime, the Incident Command

System (ICS), which had been developed by the fre service.

97

The IMS was developed for the purpose of

expanding the ICS so that other responding organizations could be similarly organized in an emergency.

98

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

20

In emergencies such as SARS and, indeed, the response to the collapse of the Algo Mall, diferent response

organizations, which do not typically coordinate their operations, are called upon to work together. The IMS

purports to coordinate a uniform response protocol among entities responding to a particular emergency. It

seeks to establish a standardized organizational structure that may be distinct from the individual responding

organizations day-to-day administrative structures. The stated purpose of having a standardized organizational

structure is to help diferent organizations work together in an emergency response including by establishing

clear terminology and roles.

99

The Incident Management System is not mandatory

As noted, one of the stated primary purposes behind the development of the IMS doctrine was to provide one

standardized emergency response system across Ontario so that diferent entities, individuals, and organizations

can more efectively respond to emergency incidents.

100

Indeed, the provincial

government recommends that the IMS be used for managing all incidents.

101

However, the IMS is not mandatory; rather, it is voluntary.

102

In fact, it provides

that responders are able to use only those aspects of the doctrine that are

suited to a given incident.

103

As a practical matter, therefore, organizations that are involved in emergency

response such as fre, police, and emergency management services are

not required to use the IMS doctrine in their day-to-day operations. It exists

theoretically and may be used within emergency response organizations

selectively, or, presumably, not at all. In his evidence before the Commission,

Mr.Hefkey was not able to advise what percentage of emergency response

organizations in the province actually use the IMS doctrine in their operations.

It follows that certain emergency response organizations use IMS more than

others do and have a correspondingly greater familiarity with its components. Accordingly, not all response

organizations share the same level of understanding of the doctrine.

In introducing the doctrine, the province recognized that achieving a standardized IMS that cuts across

organizational boundaries may necessarily involve cultural shifts, over time, among some incident management

practitioners. The province also stated that province-wide implementation is envisaged over time The

expectation is that gradually all of Ontarios response organizations will implement the IMS and will train their

personnel in the content of this doctrine to the extent deemed necessary by their respective organizations.

104

The extent to which Ontarios emergency responders exhibited familiarity with the IMS will be considered

later in this Report.

Incident Management System organizational structure and

management functions

Five major management functions provide the foundation on which the IMS is structured. These fve are

command, operations, planning, logistics, and fnance and administration.

105

These functions must form part of

every incident response.

106

The IMS literature depicts the structure as in fgure 2.2.2.

One of the stated primary

purposes behind the

development of the IMS

doctrine was to provide one

standardized emergency

response system across Ontario

so that diferent entities,

individuals, and organizations

can more efectively respond

to emergency incidents.

Chapter 2 Background of Responders and Emergency Management

21

Command

Command is the paramount organizational component of the IMS structure. It is the act of directing, ordering,

or controlling the operation of an emergency response.

107

Incident command is responsible for managing the

response to an emergency event.

Under the IMS doctrine, there are two models of incident command that may be used during an incident: single

and unifed. A single command model may be arrived at by default when only one jurisdiction or organization

is involved; by the nature of the emergency; or by legislation, if the responsibility is legally that of a single

jurisdiction or organization.

108

In a unifed command situation, two or more organizations that are participating in the emergency response

designate members to be a part of the unifed command. Those participants are intended to work together

to establish and implement a common set of objectives. It is, in essence, command by committee. Unifed

command is to be used on rare occasions when incident decision-making is complex, interdependent, and a

single command cannot be established.

109

The incident commander

The individual who exercises the command function is known as the incident commander. An incident

commander has overall authority and responsibility for conducting emergency response operations and is

responsible for the management of all operations at the location of the incident. In a single command situation,

only one person will exercise the function of the incident commander at any one time. Therefore, while several

jurisdictions may respond, there will be only one incident commander.

110

The IMS is intended to operate so that all responders from diferent jurisdictions and organizations are working

toward a common goal. It contemplates the integration of resources and personnel, with the result that the

incident commander may be from a diferent service than many of the other responders. This arrangement

creates a cultural anomaly where persons can be commanded by individuals who are not from their own

organization or who may even hold a lower rank.

Assuming incident command means taking overall responsibility for managing the incident and providing the

overall leadership. According to the IMS doctrine, command must be clearly established at the beginning of an

incident and maintained until the end.

111

Figure 2.2.2 The Incident Management System organizational structure

Source Exhibit 887

Command

Operations Planning Logistics

Finance /

Administration

Report of the Elliot Lake Commission of Inquiry Part Two

n

The Emergency Response and Inquiry Process

22

Although there is only one incident commander, that function may transfer from one individual to another. Any

such transfer of command always requires that there be a full briefng for the incoming incident commander and

notifcation to all personnel that a change in command is taking place.

112

The incident commanders responsibilities include

ensuring the safety of all responders;

assessing and reassessing the situation, which may require obtaining information from other

levels of response;

determining goals, strategies, objectives, and priorities appropriate to the level of response;