Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Balakrishnan MGRL Solutions Ch07

Uploaded by

dee0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

328 views50 pagesThis document discusses operating budgets and the budgeting process. It covers:

1) Operating budgets reflect short-term decisions that conform to long-term plans and quantify outcomes in financial statements.

2) Budgets are made for revenue, production, materials, labor, overhead, and cash to plan and control resources.

3) The budgeting process can be top-down or bottom-up and incremental changes are easier to implement than large changes.

Original Description:

Managerial accounting chapter 7 links and values

Original Title

Balakrishnan Mgrl Solutions Ch07

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses operating budgets and the budgeting process. It covers:

1) Operating budgets reflect short-term decisions that conform to long-term plans and quantify outcomes in financial statements.

2) Budgets are made for revenue, production, materials, labor, overhead, and cash to plan and control resources.

3) The budgeting process can be top-down or bottom-up and incremental changes are easier to implement than large changes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

328 views50 pagesBalakrishnan MGRL Solutions Ch07

Uploaded by

deeThis document discusses operating budgets and the budgeting process. It covers:

1) Operating budgets reflect short-term decisions that conform to long-term plans and quantify outcomes in financial statements.

2) Budgets are made for revenue, production, materials, labor, overhead, and cash to plan and control resources.

3) The budgeting process can be top-down or bottom-up and incremental changes are easier to implement than large changes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 50

CHAPTER 7

OPERATING BUDGETS: BRIDGING PLANNING AND CONTROL

SOLUTIONS

REVIEW QUESTIONS

7.1 A plan for using limited resources.

7.2 Firms budget for (1) planning, (2) coordination, and (3) control (performance evaluation

and feedback).

7.3 Operating budgets reflect the collective epression of numerous short!term decisions that

conform to the direction set b" long!term plans. Financial budgets #uantif" the outcomes

of operating budgets in summar" financial statements.

7.4 $he revenue budget. Organi%ations begin &ith the revenue budget because it is the first

line on the income statement. Additionall", organi%ations begin &ith the revenue budget

because revenues dictate the volume of operations &hich, in turn, drive man" costs such

as those related to materials and labor.

7.5 $he production budget.

7.6 $he budgets for materials, labor, and overhead.

7.7 'ost of goods sold ( 'ost of beginning finished goods inventor" ) cost of goods

manufactured * cost of ending finished goods inventor".

7.8 $he cash budget is important for managing a firm+s &orking capital. ,t allo&s companies

to determine &hether the" &ill have enough mone" on hand to sustain pro-ected

operations.

7.9 (1) ,nflo&s from operations, (2) outflo&s from operations, and (3) special items.

7.1 .ecause most businesses offer credit terms to their customers * as such, the" receive cash

a fe& da"s, &eeks, or months after the sale occurs. /oreover, a firm+s credit polic"

affects the timing and amount of cash flo&s.

7.11 (1) 0urchases of direct materials, (2) pa"ments for labor, (3) ependitures on

manufacturing overhead, and (1) outflo&s for marketing and administration costs.

7.12 2ome eamples include the purchase or sale of e#uipment, the purchase or sale of stock,

and the pa"ment of dividends.

7.13 A responsibilit" center is an organi%ational subunit. $here are three t"pes of responsibilit"

centers3 (1) cost centers, (2) profit centers, and (3) investment centers.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1

7.14 $op!do&n is more of an authoritative approach, &hereas a bottom!up approach is more

participative, encouraging organi%ation!&ide input into the budgeting process.

7.15 An incremental approach to budgeting can be useful as past trends ma" help &ith future

pro-ections. ,t is pragmatic, as it focuses attention on making changes to the previous

"ear+s budget based on actual performance and ne& information. Finall", incremental

changes are easier to -ustif" and communicate * it is human nature to compare

performance across people and periods.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

7.16 $he span of the operation often determines the need for a formal budget. ,t is easier to

plan and keep track of &hat is happening if the operation is small enough. As the business

epands to a point &here it is difficult one person can oversee the &hole operation and

multiple people have to make decisions &ith respect to different aspects of the business,

planning and coordination become necessar". /oreover, ho& can the o&ner of this

epanding business ensure that all other emplo"ees making the various decisions are in

fact making them as he &ould make them; 2ome control also becomes necessar"<

.udgets serve these purposes.

7.17 9es, this is in general a true statement. =aving a formal &ritten document that different

decision units commit to is the most efficient of ensuring that there is proper coordination

and there is goal congruence across these units.

7.18 ,t is true that there is al&a"s likel" to some deviation from &hat is epected. .ut,

deviations can occur because of factors outside decision makers+ control, and there is not

much one can do to avoid these chance deviations. >eviations can also occur because the

organi%ational actions and decisions are not in line &ith &hat the" &ere epected to do.

." providing a baseline for comparison, budgets allo& us to measure and anal"%e these

deviations so that corrective actions can be taken &hen necessar".

7.19 ,f budgets can be used to create the right organi%ational incentives, and all decision

makers in the organi%ations are motivated to do the right thing, then close supervision

ma" not be necessar". =o&ever, as discussed in the chapter, budgets cannot be a perfect

substitute for supervision monitoring because the" are susceptible to game!pla"ing? no

budget can be perfect &hen it comes to setting the right incentives. 2ome supervision and

monitoring is al&a"s beneficial.

7.2 .udgets pla" a limited role as a benchmark for performance evaluation in settings &here

forecasting is difficult and there is a high level of inherent uncertaint". =o&ever, it is

better to have rough budgets than no budgets at all, and supplement budgets &ith other

monitoring mechanisms such as close supervision.

7.21 >epending on the si%e of the organi%ation and the number of products it offers,

forecasting sales is a difficult eercise because it re#uires careful eamination of market

conditions and trends. ,naccurate sales forecasts can thro& the entire planning process out

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2

of gear. 2o, man" organi%ations devote a lot of time to develop dependable sales

forecasts. 7stimating overheads is also difficult especiall" in large organi%ations because

there are multiple drivers of overhead. ,dentif"ing the right drivers and estimating the

precise relations bet&een the overhead and its drivers is a difficult but an important step

in the budgeting process.

7.22 @ust!in!s"stem is often referred to as a ApullB s"stem because an order from a customer

triggers all the production and procurement activities. $he idea is to carr" no inventor" in

the s"stem, but respond to demand #uickl" b" achieving b" coordinating all necessar"

activities smoothl". $o the etent a perfect pull s"stem can be achieved there are minimal

inventor" budgets that reconcile the difference bet&een sales and production. 2imilarl",

there are minimal ra& and &ork!in!process inventories that account for the difference

bet&een material purchase and use.

7.23 $he budgeting process is time consuming in most organi%ations. 2ome large

organi%ations are kno&n to start their budgeting process si months ahead of time. $he

benefit of going through several iterations is that budgets become more accurate, serve as

better benchmarks to evaluate performance, and there is better coordination across the

organi%ation because ever"bod" is a&are of &hat is in it. $he cost is that it takes time and

effort.

7.24 .oth the cash budget and cash flo& statement reconcile the cash position of a compan" at

the beginning of a period to the cash position at the end of the period. .ut there are man"

differences. First, the cash flo& statement is prepared at the end of the period, and reports

past cash inflo&s and outflo&s. 2econd, the cash flo& statement reports cash flo&s

associated &ith investing, financing, and operating decisions of the firm. On the other

hand, a cash flo& budget presents a plan of cash inflo&s and outflo&s at a more detailed

level, such as &hen and ho& much cash is epected from customers, &hen cash is to be

paid to suppliers, and &orking capital re#uirements.

7.25 2ome believe that budgets promote a financial emphasis in organi%ations. ,t is true that

budgets are mostl" financial plans of organi%ational activities. $he reason for this is that

ultimatel" the performance of a compan" is -udged in terms of the financial returns it

generates for its shareholders. .ut budgets need not necessaril" be restricted to financial

measures. /an" firms are no& benchmarking ke" non!financial measures to ensure

organi%ational success.

7.26 .oth lines of reasoning have merit. For gro&th companies, it is often difficult to develop

precise budgets because of the difficult" in forecasting outcomes from research and

development and other gro&th activities. /oreover, rigid budgets are often said to stifle

innovation and gro&th b" not giving enough room to eercise discretion to sei%e

opportunities in a timel" fashion. On the other hand, budgets that allo& discretion are

also sub-ect to misuse because formal control is difficult. Often more informal control

mechanisms and closer supervision are needed to achieve a measure of control in such

organi%ations.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!3

7.27 $he advantages of participative budgeting include benefiting of the epertise and

kno&ledge of emplo"ees in all levels of the organi%ation b" involving them in the

budgeting process, promoting a sense of o&nership and empo&erment among all

emplo"ees, ensuring that ever"bod" bu"s into the budget so that implementation is

smooth, better communication and coordination. $he disadvantages are that participative

budgeting is time consuming, and can lead to conflicts and disagreements that are hard to

resolve (as the sa"ing goes !! Atoo man" cooks spoil the broth<B).

7.28 $op!do&n budgeting is preferable &hen decisions need to be taken #uickl", and time is of

essence. $op!do&n budgeting is most suitable in smaller organi%ations &ith a narro& and

manageable range of products and services, and centrali%ed decision making. ,n these

settings, top managers are likel" to possess detailed enough information for budgeting

purposes.

7.29 8ine!item budgeting is a term used to refer to budgets that are built line!item b" line!

item. 6suall", budget for line!item cannot be used for another line item even if there is

still some mone" left in it. ,n the government, for eample, each line item in the budget

represents a certain use of public mone" such as road construction, maintenance of public

buildings, parks, medical care, public securit" etc. $he reason for not allo&ing

appropriation of funds set aside for one line!item for another purpose is to ensure the no

public good or service is left underfunded. 2imilar considerations appl" to nonprofit

organi%ations. $hese considerations are not as applicable to commercial companies &here

the &hole purpose is to allocate funds in a &a" that generates most profits.

7.3 A budget is said to lapse if an" unspent amount in the budget is not carried over to the

net period. 9es, the criticism is valid. $here are man" documented instances of such

behavior. =o&ever, budget lapsing is a good &a" to force ependitures on some desirable

activities and causes. 4esearch and development budgets are a good eample in

commercial organi%ations.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1

E!ERCISES

7.31

,n solving budgeting eercises, &e repeatedl" use the Ainventor" e#uation.B ,n its

simplest form, the inventor" e#uation is3

Beginning balance ) What we put in * What we take out ( Ending balance.

Ce replace these terms &ith the appropriate account!specific terms &hen computing

specific revenue and cost budgets.

For 0remium, &e have3

.eginning inventor" 1,:DE Cindo&s

) 0roduction F,EEE

! 2ales ;

( 7nding inventor" 2,DEE &indo&s

$hus, &e find S"#$% &'( )"(*+ , 7-25 ./01'.%.

/ultipl"ing :,2DE &indo&s b" the GHE price per &indo& gives 2314$5$1 )"(*+

($6$03$ '& 7435-.

7.32

a. $his eercise illustrates that budgets allo& organi%ations to pro-ect results for various

options, helping them make the profit!maimi%ing choice. .elo&, &e calculate the

annual sales and revenues for each price.

S"#$% R$6$03$%

)'05+ Price = $60 Price = $57 Price = $60 Price = $57

@anuar" 2,DEE 2,HEE G1DE,EEE G11F,2EE

Februar" 2,HEE 2,:2D 1DH,EEE 1DD,32D

/arch 2,:EE 2,FDE 1H2,EEE 1H2,1DE

April 2,FEE 2,I:D 1HF,EEE 1HI,D:D

/a" 2,IEE 3,1EE 1:1,EEE 1:H,:EE

@une 3,EEE 3,22D 1FE,EEE 1F3,F2D

@ul" 3,1EE 3,3DE 1FH,EEE 1IE,IDE

August 3,2EE 3,1:D 1I2,EEE 1IF,E:D

2eptember 3,EDE 3,32D 1F3,EEE 1FI,D2D

October 2,IEE 3,1:D 1:1,EEE 1FE,I:D

5ovember 2,:DE 3,E2D 1HD,EEE 1:2,12D

>ecember 2,HEE 2,F:D 1DH,EEE 1H3,F:D

T'5"#% 34-1 36-7 72-46- 72-91-9

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!D

Ce see that pricing at GD: maimi%es 0remium+s revenues. 7ven though the compan"

receives a smaller amount for each Cindo&, the increased volume compensates for the

lo&er price.

b. 0erhaps the most important factor to consider is cost * after all, 0remium is interested

in maimi%ing profit, not -ust revenues. 0ricing its product at GD:, 0remium &ill be

selling additional 2,HEE &indo&s (3H,:EE * 31,1EE) over the course of the "ear.

=o&ever, reducing the price &ill not increase profit unless the additional costs of

producing and selling the etra &indo&s are less than G1D,IEE (( G2,EI1,IEE !

G2,E1H,EEE) or about G1D,IEEJ2,HEE ( G1:.HD per &indo&. Along these lines,

0remium must consider &hether it has enough capacit" to produce the higher volume,

and if the higher volume might add to congestion in the factor".

0remium also needs to consider the accurac" of its demand forecasts and &hether a price

cut &ould adversel" affect the perceived #ualit" of its product. Finall", 0remium needs to

consider &hat its competitors &ill do in terms of their pricing strateg" * if competitors

also reduce their prices, 0remium ma" not en-o" the increase in forecasted demand.

7.33

Ce can appl" the inventor" e#uation to find the missing data, as follo&s3

Number of Window !pril

"eptembe

r #ecember

>esired ending inventor" 1,FEE 2,EEE 3,2EE

) .udgeted sales 1E,EEE 1D,EEE 2E,EEE

( $otal re#uirements 11,FEE 1:,EEE 23,2EE

! .eginning inventor" 1,2EE 3,EEE 2,2EE

( .udgeted production 1-6 11,EEE 21,EEE

,n each instance, &e perform the suitable arithmetic to rearrange the terms and solve for

the re#uired item.

7.34

$o begin, &e kno& that3

.eginning inventor" (/arch) ( 7nding inventor" (Februar")

and,

>esired ending inventor" (Februar") ( 1DK of /arch sales.

( E.1D L 1D,EEE ( 2,2DE.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!H

Cith this step, &e can fill in the table partiall"3

Number of Window

$ebruar

% &arch !pril

>esired ending inventor"

M

2-25 3- 3,EEE

) .udgeted sales 1E,EEE 1D,EEE 2E,EEE

( $otal re#uirements 12,2DE 1F,EEE 23,EEE

! .eginning inventor"

MM

1,DEE 2-25 3-

( .udgeted production 8 8 8

M 2,2DE ( E.1D L 1D,EEE? 3,EEE ( E.1D L 2E,EEE

MM .eginning inventor" (/arch) ( 7nding inventor" (Februar").

Ce then use the inventor" e#uation to fill in the missing data, as follo&s3

Number of Window

$ebruar

% &arch !pril

>esired ending inventor" 2-25 3- 3,EEE

) .udgeted sales 1E,EEE 1D,EEE 2E,EEE

( $otal re#uirements 12,2DE 1F,EEE 23,EEE

! .eginning inventor" 1,DEE 2-25 3-

( .udgeted production 1-75 15-75 2-

,n each instance, &e perform the suitable arithmetic to rearrange the terms and solve for

the re#uired item. ,n particular, &e first solve for Februar" ending inventor" and Februar"

production. ,n turn, this gives us the .eginning inventor" for /arch. Ce repeat the

process for /arch to get /arch production, and so on.

7.35

a. $he follo&ing table provides the re#uired revenue budget, and income statement.

August 2eptember October 5ovember

,ndividuals :EE HIE HFE H:D

Famil" memberships 3EE 3EE 2ID 2IE

4evenue ! ,ndividual G :E,EEE

1

G HI,EEE G HF,EEE G H:,DEE

4evenue ! Famil" G 1F,EEE

1

G 1F,EEE G 1:,2EE G 1H,1EE

$otal 4evenue G 11F,EEE G 11:,EEE G 11D,2EE G 113,IEE

Nariable cost *

,ndividual G 21,DEE

1

G 21,1DE G 23,FEE G 23,H2D

Nariable cost ! Famil" G 1F,EEE

1

G 1F,EEE G 1:,:EE G 1:,1EE

'ontribution margin G :D,DEE G :1,FDE G :3,:EE G :2,F:D

Fied cost G 1E,EEE G 1E,EEE G 1E,EEE G 1E,EEE

0rofit before taes G 3D,DEE G 31,FDE G 33,:EE G 32,F:D

1

G:E,EEE ( :EE L 1EE? G1F,EEE ( 3EE L G1HE? G21,DEE ( :EE L G3D? G1F,EEE ( 3EE L GHE.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!:

b. $he follo&ing table provides the re#uired revenue budget, and income statement.

August

2eptember October

5ovember

,ndividuals :EE :EE HIE HFD

Famil" memberships 3EE 3ED 3EE 2ID

4evenue ! ,ndividual G:E,EEE G:E,EEE GHI,EEE GHF,DEE

4evenue ! Famil" 1F,EEE 1F,FEE 1F,EEE 1:,2EE

$otal 4evenue G11F,EEE G11F,FEE G11:,EEE G11D,:EE

Nariable cost ! ,ndividual G21,DEE G21,DEE G21,1DE G23,I:D

Nariable cost ! Famil" 1F,EEE 1F,3EE 1F,EEE 1:,:EE

'ontribution margin G:D,DEE G:H,EEE G:1,FDE G:1,E2D

Fied cost 1E,EEE 1E,EEE 1E,EEE 1E,EEE

Ad campaign 1E,EEE

0rofit before taes G3D,DEE G2H,EEE G31,FDE G31,E2D

c. .ased on the above, it &ould appear that profits have decreased. .ased on pro-ection

in part OaP, =ercules epected to earn G13H,I2D (( G3D,DEE ) G31,FDE ) G33,:EE )

G32,F:D). $he pro-ection in part ObP sho&s a cumulative profit of G13E,3:D ((

G3D,DEE ) G2H,EEE ) G31,FDE ) G31,E2D) onl", a decrease of about GH,DDE. =o&ever,

&e cannot conclude that the ad campaign is a bad idea. $his is because the ne&

members &ill continue to benefit =ercules in the future as &ell (but not indefinitel").

2uppose that the average ne& membership is for 12 months. $hen, the epected

benefit from the campaign is 12 months L O1E individuals L (G1EE!G3D) ) D familiesL

(G1HE *GHE) P ( G13,FEE, &hich eceeds the cost of the ad campaign.

5ote3 Firms develop Alife!c"cleB models to account for such future effects. 2uch models

are crucial in service firms such as cable operators and &ireless providers &ho epect to

get a continuing stream of revenue from each ne& customer. $hus, these firms are &illing

to take a AlossB in the first fe& months b" spending a lot to get ne& customers.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!F

7.36

$he follo&ing table provides the re#uired information. 5otice the use of the inventor"

e#uation to back out the amount of purchases.

August 2eptember October

,ndividuals :EE HIE HFE

Famil" memberships 3EE 3EE 2ID

2upplies needed 13,HEE

1

13,DEE 13,2IE

7nding inventor" D,EEE 1,DEE 1,DEE

($otal needed 1F,HEE 1F,EEE 1:,:IE

!.eginning inventor" D,EEE D,EEE 1,DEE

( 0urchases 713-6 713- 713-29

1

13,HEE ( :EE L 1E ) 3EE L 22.

5otice that the beginning inventor" in 2eptember is the ending inventor" in August. Ce

also calculate supplies needed as Q of individual memberships L G1E ) Q of famil"

memberships L G22. Finall", notice that &e cannot compute the purchases in 5ovember

because &e do not kno& the re#uired ending inventor".

7.37

8et us begin b" calculating the operating cash flo&.

Item Detail September

,ndividual fees (HIE!1FE)L G1EE GD1,EEE

Famil" (3EE * HE) L G1HE 3F,1EE

0repaid (individual) (1FEJ12) M (12 L 1EE L IEK) 1H,2EE

0repaid (famil") (HEJ12) L (12 L 1HE L IEK) F,H1E

$otal inflo&s G111,21E

0urchase (current) E.H L G13,EEE G :,FEE

0urchases (prior) E.1 L G13,HEE D,11E

Nariable costs (HIE L G2D) ) (3EE L G1D) 3E,:DE

Fied costs G11,EEE !G12,DEE 2F,DEE

$otal outflo&s G:2,1IE

Operating cash flo& G11,:DE

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!I

Ce can no& prepare the cash budget.

Item September

.eginning balance G H,EEE

Operating cash flo& 11,:DE

2pecial items ! e#uipment (2E,EEE)

Amount taken out (1D,EEE)

7nding balance G12,:DE

7.38

$his eercise is Atrick"B in the sense that &e cannot directl" appl" the inventor" e#uation

to the ne& sales pro-ection for April. $his is because &e do not kno& the original or

revised sales for April. =o&ever, &e kno& the original production for April. 6sing this

data, &e can back out the original sales as 113,EEE units (as sho&n in the table belo&).

$he revised sales therefore ( IEK of 113,EEE ( 1E1,:EE units. Ce could then back out

the ($6/%$1 9('13*5/'0 &'( A9(/# "% 16-5 30/5%. 5otice that there is no change in the

beginning inventor" for April. $his is because /arch is almost over and Rant% &ould

have alread" built up inventor" as per the original budget. =o&ever, because /a"+s

estimates are do&n 1EK, the desired ending inventor" for April &ould be do&n 1EK,

from 22,EEE to 1I,FEE.

A9(/# :'#1; A9(/# :0$.;

>esired ending inventor" 22,EEE E.I L 22,EEE ( 1I,FEE

) .udgeted sales 113,EEE

1

E.I L 113,EEE ( 1E1,:EE

( $otal re#uirements 13D,EEE 121,DEE

! .eginning inventor" 1D,EEE 1D,EEE

( .udgeted production 12E,EEE 16-5

1

113,EEE ( 12E,EEE ) 1D,EEE * 22,EEE.

7.39

$he ke" point in this problem is that &e have to perform the calculations separatel" for

each t"pe of bo (although &e use the same inventor" e#uation for all boes).

Additionall", it+s important to remember that the ending inventor" for an" one month

e#uals the beginning inventor" of the follo&ing month * thus, &e can calculate the

beginning inventor" for /arch as 2EK of /arch+s sales (&hich is the ending inventor" of

Februar").

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1E

S<"## 2'=$%:

&arch !pril

>esired ending inventor"

( (.2E L net month+s sales) 3,EEE 1,EEE

) .udgeted sales 1E,EEE 1D,EEE

( $otal 4e#uirements 13,EEE 1I,EEE

! .eginning inventor"

( (.2E L current month+s sales) 2,EEE 3,EEE

( B314$5$1 9('13*5/'0 11- 16-

R$6$03$ 2314$5 (( 2ales L G2.:D) 727-5 741-25

)$1/3< 2'=$%:

&arch !pril

>esired ending inventor"

( (.2E L net month+s sales) H,EEE F,EEE

) .udgeted sales 2D,EEE 3E,EEE

( $otal re#uirements 31,EEE 3F,EEE

! .eginning inventor"

( (.2E L current month+s sales) D,EEE H,EEE

( B314$5$1 9('13*5/'0 26- 32-

R$6$03$ B314$5 (( 2ales L G3.:D)

793-75

7112-5

L"(4$ 2'=$%:

&arch !pril

>esired ending inventor"

( (.2E L net month+s sales) 1,EEE D,EEE

) .udgeted sales 1D,EEE 2E,EEE

( $otal re#uirements 1I,EEE 2D,EEE

! .eginning inventor"

( (.2E L current month+s sales) 3,EEE 1,EEE

( B314$5$1 9('13*5/'0 16- 21-

R$6$03$ B314$5 (( 2ales L GD.EE) 775- 71-

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!11

7.4

a. Once again, &e appl" the inventor" e#uation to solve this problem. 6sing the

information provided, &e have (units in linear feet)3

)"(*+ >etail

>esired ending inventor"

(in linear feet)

:D,F1E 1EK of April needs (

E.1E L 1D,FEE boes L

12 feetJbo.

) 5eeded for production 111,EEE 12,EEE boes to be

produced L 12 feetJbo.

( $otal re#uirements 21I,F1E

! .eginning inventor" DE,EEE Riven

( B314$5$1 93(*+"%$%

(linear feet)

169-84

P3(*+"%$% 2314$5 (

budgeted purchases L GE.:D

per foot

7127-38

b. .os&orth &ould use 111,EEE linear feet of cardboard strips to produce the boes. T+$

5'5"# <"5$(/"#% *'%5 ( 111,EEE L GE.:D ( 718-. An inventor" cost flo&

assumption is not re#uired in this instance because the entire inventor" (beginning

inventor" plus purchases) is valued at GE.:D per linear foot.

c. .ecause .os&orth has different la"ers of inventor" &ith differing prices, the cost

flo& assumption no& becomes important. Cith F,FO, the firm &ill consume the

oldest la"er first before consuming purchases.

$hus, &e have3

From beginning inventor" DE,EEE linear feet S GE.:EJft

G3D,EEE

From /arch purchases I1,EEEM linear feet SGE.:DJft G:E,DEE

T'5"# <"5$(/"#% *'%5 715-5

M I1,EEE ( 111,EEE * DE,EEE

5otice that the cost of materials usage has decreased. Ch";

6nder the F,FO cost flo& assumption used b" .oso&orth, the materials in beginning

inventor" &ill be used up first. .os&orth+s beginning inventor" is valued at G3D,EEE.

$hat difference of G2,DEE (DE,EEE linear feet L E.EDJft) causes the cost of material usage

to decrease.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!12

5ote3 $he usage budget for /arch &ould not change if .os&orth uses the 8,FO method.

$he firm &ould not be dipping into the la"er of beginning inventor", meaning that all

111,EEE linear feet used &ould be valued at GE.:D per foot.

7.41

Ce compute budgeted cash inflo&s using the follo&ing table3

N'6$<2$( D$*$<2$(

4evenues G13D,EEE G1DE,EEE

'ash collections from current revenues 1E,DEE 1D,EEE

'ash collected one month later DH,EEE D1,EEE

'ash collected t&o months later 33,:DE 3D,EEE

'ash collected three months later H,EEE H,:DE

T'5"# C"%+ C'##$*5/'0% 7136-25 714-75

5otice that the collections for 5ovember include 3EK of 5ovember sales (E.3E L

G13D,EEE), 1EK of October sales (E.1E L G11E,EEE), 2DK of 2eptember sales (E.2D L

G13D,EEE), and DK of August sales (E.ED L G12E,EEE). Ce need to stagger sales in this

fashion because it takes .ruce 3) months to collect cash from his sales.

7.42

As &ith the prior problem (&hich deals &ith receivables), it is most convenient to

calculate .ruce+s cash outflo&s using a table such as the follo&ing3

O*5'2$( N'6$<2$( D$*$<2$(

0urchases 12E,EEE 11E,EEE 12E,EEE

'ash pa"ment for current purchases G:2,EEE GHH,EEE G:2,EEE

'ash pa"ment for prior month purchase 2F,DEE 3H,EEE 33,EEE

'ash pa"ment for purchases made 2 months ago I,EEE I,DEE 12,EEE

T'5"# C"%+ O35&#'. 719-5 7111-5 7117-

5otice that the total cash outflo& for >ecember includes pa"ments for >ecember

purchases (E.HE L 12E,EEE), for 5ovember purchases (E.3E L 11E,EEE), and for October

purchases (E.1E L 12E,EEE). Ce compute the cash outflo&s for October and 5ovember in

a similar fashion.

7.43

$he follo&ing items pertain to October, and illustrate the logic for the cash budget.

1. $otal cash available ( beginning balance ) receipts ( GI,DEE ) G11,1EE ( G23,HEE.

2. $otal disbursement ( 2um of pa"ments for materials, labor and overhead. .acking

out the numbers, for the pa"ments for overhead &e have G1F,3EE !G1,1EE !GF,1DE (

GD,1DE

3. .alance prior to financing ( total available * total pa"ments (or, disbursements).

$hus, G23,HEE ! G1F,3EE ( GD,3EE.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!13

1. .orro&ing needed (if an") ( /inimum balance * balance prior to financing.

D. 7nding balance (October) ( .eginning balance (5ovember)

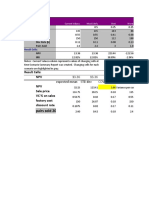

$he follo&ing table provides the completed cash budget.

C"%+ B314$5 > ?'3(5+ Q3"(5$(

'ctobe

r

No(embe

r

#ecembe

r

.eginning cash balance GI,DEE GI,DEE GI,DEE

'ash receipts 11,1EE 17-9 18-4

$otal cash available 723-6 G2:,1EE G2:,IEE

'ash disbursements

0a"ments for materials 1,1EE 3-63 1,1EE

0a"ments for labor F,1DE :,2DE 7-21

0a"ments for overhead 5-45 D,I2E D,:2E

$otal disbursements 1F,3EE 1H,FEE 1:,E3E

.alance prior to financing 5-3 1-6 1-87

/inimum cash balance I,DEE I,DEE I,DEE

Financing

.orro&ingJ(repa"ment) 4-2 :1-1; :1-37;

7nding cash balance 79-5 79-5 79-5

$he firm+s ending loan balance is therefore G1,2EE ! G1,1EE ! G1,3:E ( 71-73.

7.44

$he follo&ing table provides Rilbert+s cash budget for 5ovember and >ecember.

No(ember #ecember

Opening balance of cash G1H,EEE G2:,EEE

) 4eceipts from current sales (:EK of

current revenues)

3D,EEE 12,EEE

) 4eceipts from prior month sales (3EK of

prior month revenues)

12,EEE 1D,EEE

( $otal available GH3,EEE GF1,EEE

! 0urchase cost

(( 'OR2 ( HEK of revenues)

3E,EEE 3H,EEE

! /arketing and admin. epenses H,EEE D,EEE

7nding balance of cash 727- 743-

5otice that Rilbert+s 5ovember collections include :EK of 5ovember sales (G3D,EEE)

and 3EK of October sales (G12,EEE). .ased on our anal"sis, it appears that Rilbert &ill

have plent" of cash on hand and, thus, &ill not need to borro& mone".

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!11

7.45

a. Ce can do this problem in t&o &a"s. $he short method is to recogni%e that Tris

&ould have collected all of her sales for /arch and April b" /a" 31. 2he also &ould

have collected DEK of /a" sales in /a". $hus, her accounts receivable &ould be

DEK of /a" sales or 723- (( G1H,EEE L E.DE).

$he longer method is to &rite do&n her accounts receivable, using a format similar to

that for inventor" accounts. Ce have3

A9(/# )"@

Opening balance for receivables G2D,EEE G2E,EEE

) 'urrent sales 1E,EEE 1H,EEE

( $otal collectible GHD,EEE GHH,EEE

! 'ollections for prior month 2D,EEE 2E,EEE

! 'ollections for current month 2E,EEE 23,EEE

'losing balance for receivables 72- 723-

b. Again, &e can do this problem in t&o &a"s. $he short method is to recogni%e that

Tris &ould have paid for all of her purchases in /arch and April b" /a" 31. 2he also

&ould have paid for FEK of purchases in /a". $hus, her accounts pa"able &ould be

2EK of /a" purchases or E.2E L G1E,EEE ( 78-.

$he longer method is to &rite do&n her accounts pa"able, using a format similar to that

for inventor" accounts. Ce have3

A9(/# )"@

Opening balance for pa"ables GH,EEE GH,1EE

) 'urrent purchases 32,EEE 1E,EEE

( $otal pa"able 3F,EEE 1H,1EE

! 0a"ments for prior month H,EEE H,1EE

! 0a"ments for current month 2D,HEE 32,EEE

'losing balance for pa"ables 76-4 78-

7.46

$his is an open!ended #uestion &ith man" possible vie&s on the Cilma+s best course of

action. Ce summari%e some possible arguments belo&.

2ome might argue that Cilma should follo& 2cott Ford and @ake+s 8e&is lead and pad

her budget as &ell. $he problem appears to be ver" rigid standards and a formulaic

approach to incentive compensation. $he founder+s approach, some ma" argue, leaves the

managers no choice, but to build in some cushion. ,ndeed, &e might -ustif" @ake+s actions

as beneficial in the long term, although &e onl" have his &ord that the cushion is for

long!term improvements. 2ome might #uestion 2cott+s AecessiveB lo&!balling, although

ho& much is AOTB and ho& much is AecessiveB is not resolved easil".

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1D

At the other etreme, clearl" the firm+s plans contain information kno&n to be false.

7thical standards for accounting professionals preclude Cilma from kno&ingl"

compromising the integrit" of information. $hus, she might have no choice but to tr" and

rectif" the situation as much as possible. >oing so, ho&ever, might pit her against the

other managers, limiting her effectiveness.

Overall, a pragmatic approach might involve attempting to educate the o&ner about the

pitfalls of his methods. ,ndeed, Cilma might find that 4o" is &ell a&are of the padding

b" his managers and that this is the Ugame+ that all in the firm agree to (implicitl"). ,n this

case, Cilma+s conscience is clear and, in our opinion, she &ould compl" &ith accounting

standards as &ell. $hus, our recommendation is for Cilma to speak &ith 4o" and feel

him out on his vie&s about budget padding before taking the net step.

7.47

$his #uestion is likel" to provoke a range of ans&ers. 'learl", the manager eperienced

an unfavorable and uncontrollable event. 9et, should 'arrie revise the budget; Ce see the

issue as t&o separate problems. $he first is a planning problem in terms of scheduling

production, ordering materials, and so on. 5aturall", the firm should take the latest

information into account for such decisions.

$he second problem is &hether the manager+s performance targets should be changed.

One could argue either for or against a change * &e are inclined to not change the

performance targets in this instance. First, as 'arrie notes, a change re#uires that she

define a Ubig+ event, and this is a slipper" slope. ,t &ould not be long before an" adverse

event triggered a re#uest for a target reset. 2econd, good managers are supposed to deal

&ith risk. ,nsulating them against risk defeats the purpose. $hird, managers often are ver"

innovative &hen their back is against the &all. $his event might spur management into

un!chartered territor". And, the final argument is A&ill the manager ask for a target reset

if the fire &ere in a competitor) plant;B

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1H

PROBLE)S

7.48

a. .lue2teel appears to have enough capacit" to meet its annual sales forecast. Annual

sales are 112,DEE units (21,EEE ) 2F,DEE ) 33,EEE ) 2:,EEE) and the firm has

installed capacit" for 12E,EEE units (12 months L 1E,EEE units per month).

b. 'learl", .lue2teel needs to build up inventor" to meet the demand surge in V3.

.lue2teel could do this b" building up inventor" in V1 and V2. $he compan" &ould

need to begin in V1 because there is limited ecess capacit" is V2 * the ecess

capacit" in V2 is not enough to make the etra units to meet the demand for V3.

$he follo&ing table illustrates one possible production schedule that enables the firm to

meet its sales forecast.

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4

2ales for #uarter 21,EEE 2F,DEE 33,EEE 2:,EEE

0roduction for #uarter 2D,DEE 3E,EEE 3E,EEE 2:,EEE

,nventor" at end of #uarter 1,DEE 3,EEE E E

,n realit", the firm might &ish to build up more inventor" in V1 so that the factor" has

some slack in V2 and V3 to deal &ith unanticipated problems.

Another alternative is to produce something like 2F,DEE? 2F,DEE? 2F,DEE, 2:,EEE cabinets

in the four #uarters. $his schedule smoothes out production (from a hiring standpoint),

leaves some additional capacit" in V2 and V3 if needed, and lightens a bit in V1, perhaps

for additional maintenance, and to secure desired "ear!end inventor".

c. $he '7O+s basic approach appears to be sound. /odern management practice is to

limit the amount of inventor" as much as possible. 2uch curtailing of capacit" has

several advantages. First, it reduces the capital tied up. 2econd, it reduces

obsolescence. $hird, a lo& inventor" polic", if done in con-unction &ith suitable

changes to production processes, could help the firm improve #ualit" and increase

responsiveness.

=o&ever, the lo& inventor" polic" comes &ith a cost. For .lue2teel, a %ero inventor"

polic" &ould curtail V3 sales to 3E,EEE units. Other than building inventor", the onl"

&a" to meet demand is b" adding to capacit", &hich &ill increase capacit" for all four

#uarters.

d. ,nventor" gives firms a &a" to AmoveB capacit" across periods, as sho&n in part ObP.

=o&ever, such movement is costl" because of storage costs and the cost of capital

tied up in inventor", as &ell as intangible #ualit" costs. $he best solution is, of course,

situation specific, but the problem highlights that holding inventor" has both costs

and benefits.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1:

7.49

,t is convenient to compute /ina+s epected cash inflo&s using a table such as the

follo&ing3

O*5'2$( N'6$<2$( D$*$<2$(

2ales G1H1,EEE G1:D,EEE G1IE,EEE

'ash from current sales

G1I,2EE GD2,DEE GD:,EEE

'redit sales (current month)

3D,EEE 1D,I2E 1I,EEE

'redit (one month later)

33,2DE 13,:DE D:,1EE

'redit (t&o months later)

1,:HE D,32E :,EEE

$otal 7122-21 7 147-49 717-4

$hirt" percent of /ina+s sales are made for cash, so the collections for October include

3EK of October sales (E.3E L G1H1,EEE). $he remainder of :EK credit purchases for

October is calculated as follo&s3 1EK of the credit sales in 2eptember (E.1E L E.:E L

G12D,EEE), DEK of the credit sales in August (E.DE L E.:E L GID,EEE) and FK of the credit

sales in @ul" (E.EF L E.:E L FD,EEE). Ce need to stagger sales in this fashion because

/ina takes several months to collect cash from her sales. Ce compute the collections for

5ovember and >ecember in a similar fashion.

5otice that /ina &riting off 2K of her credit sales has no impact on her epected cash

inflo&. $he &rite off &ould, ho&ever, reduce her balance of accounts receivable b"

increasing the balance of allo&ance for doubtful accounts ($he other side of the entr" is

an epense in the income statement.)

7.5

$he numerical ans&er to this #uestion is relativel" straightfor&ard. Ash&ini &ill commit

G1DE,EEE in April, G1FD,EEE in /a" and G21E,EEE in @une. =o&ever, her bank statement

&ill record a cash outflo& e#ual to received items3 G1DE,EEE in /a", G1FD,EEE in @une,

and G21E,EEE in @ul".

$his discrepanc" bet&een committed outflo&s and actual outflo&s highlights t&o

observations. First, &e might have to pa" for some purchases before &e receive the items.

2uch arrangements are common in international settings, and in settings &here the seller

has a great deal of bargaining po&er. 2econd, Ash&ini+s actual cash outflo& (in the sense

of an outflo& from her bank account) &ould take place the same month she receives the

items. =o&ever, she needs to budget a bit differentl" because the bank &ould place a

AholdB on the mone". $his hold means that the mone" &ould not be available to Ash&ini

for other purposes.

$hus, the problem emphasi%es that cash budgets must include the commitment of cash,

even if the actual outflo& might take place later. Ce often see this in purchase budgets

that go into future months to sho& commitments triggered b" current purchases. ,n cases

like the one Ash&ini faces, firms &ould often have a separate line item for committed

funds that the" &ould remove from available cash balances.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1F

5ote3 Ash&ini+s problem is similar, in principle, to depositing a check at a bank but not

having access to the funds until the check clears.

7.51

a. $he follo&ing table provides Rar"+s income statement for October through

>ecember. ,n this statement, notice that the cost of purchases ( FEK of sales. (Rar"

marks up G1 of cost to G1.2D in sales. 2o, G1 in sales ( G1J1.2D ( GE.FE in cost.)

O*5'2$( N'6$<2$( D$*$<2$(

4evenues G1:D,EEE GD2D,EEE GDH2,DEE

0urchases cost 3FE,EEE 12E,EEE 1DE,EEE

'ontribution /argin GID,EEE G1ED,EEE G112,DEE

'ash fied costs FD,EEE FD,EEE FD,EEE

5on cash fied costs 1E,EEE 1E,EEE 1E,EEE

0rofit before taes 7 71- 717-5

Overall, Rar" appears to be running a profitable business, &ith breakeven sales of

G1:D,EEE. ('heck3 G1:D,EEE L '/4 of 2EK ! GID,EEE ( E). $hus, &hile Rar" is at

breakeven in October, he is &ell past the re#uired volume in 5ovember and >ecember.

b. $he follo&ing table provides Rar"+s cash budget for October * >ecember. ,n this

statement, 'ollections * 1 month are the collections from prior month sales (e.g.,

October ( E.3E of 2eptember sales) and 'ollections * 2 months are the collections

from sales 2 months ago (October ( E.:E L August sales). 8ike&ise, purchases *

current month ( DEK of current month purchases and purchases * 1 month are DEK

of the prior months purchases.

O*5'2$( N'6$<2$( D$*$<2$(

'ollections ! 1 month G11E,H2D G112,DEE G1D:,DEE

'ollections ! 2 months 32F,12D 32F,12D 332,DEE

$otal cash available G1HF,:DE G1:E,H2D G1IE,EEE

0urchase ! current month 1IE,EEE 21E,EEE 22D,EEE

0urchase month ago

1F:,DEE

1

1IE,EEE

2

21E,EEE

'ash fied costs FD,EEE FD,EEE FD,EEE

5et cash from operations GH,2DE (G11,3:D) (G3E,EEE)

)opening balance D,EEE 11,2DE (3,12D)

, E01/04 2"#"0*$ 711-25 :73-125; :733-125;

1

G1F:,DEE ( (1HF,:DEJ1.2D) L E.DE.

2

G1IE,EEE ( (1:D,EEEJ1.2D) L E.DE.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!1I

Overall, Rar" appears to be facing a cash crunch. Available cash dips from G11,2DE in

October to an anticipated shortfall of (G33,12D) in >ecember. $his occurs even though

sales have increased in this time period.

c. Rar"+s problem is common among firms &hich eperience gro&th. ,n essence, Rar"

is pumping mone" into &orking capital because he is financing his customers+

purchases. =e is pa"ing his suppliers faster than his customers are pa"ing him. $hus,

&hen his business gro&s, he has to put more mone" into the business. Ce can see this

b" calculating that the accounts receivable at the start of October is G:IH,F:D (( :EK

of August sales ) 2eptember sales), &hereas it is GI3E,EEE (( :EK of 5ovember sales

) >ecember sales) at the start of @anuar" net "ear.

Rar" needs to find &a"s to manage this imbalance. One avenue is to borro&, but he

has to consider interest costs. $he other avenue is to accelerate collections or defer

pa"ments, but then customers might cut back on orders and suppliers might raise

prices. .oth actions are costl" to Rar". Rar" &ould need to estimate his epected

profit to evaluate each option.

7.52

Ce kno& that the 'OR/ is the outflo& from the C,0 inventor" account. >irect

materials, direct labor, and overhead are the inflo&s into this account. Appl"ing the

inventor" e#uation then helps us fill in the re#uired data.

8ike&ise, &e kno& that the 'OR2 is the cost of the items removed from finished goods

inventor". $hus, &e can compute 'OR2 b" appl"ing the inventor" e#uation to the FR

inventor" account.

5otice that 'OR/ is the linking number bet&een the t&o accounts. $his amount is the

outflo& from the C,0 account and is the inflo& into the FR account.

8et us begin &ith the C,0 account. Ce have3

)"@ A30$

Opening C,0 G1FE,EEE 7275-5

) >irect materials usage 2DE,EEE 2FE,EEE

) >irect labor 2HD,DEE 31D,EEE

) Nariable overhead 12D,EEE 11D,EEE

( $otal inflo& into C,0 F2E,DEE 1,E1D,DEE

! Nariable cost of goods manufactured D1D,EEE D:1,EEE

( 7nding C,0 7275-5 7471-5

.eginning &ith /a", &e appl" the standard inventor" e#uation to obtain ending

inventor" as G2:D,DEE. $he ending inventor" in /a" is the beginning inventor" for @une.

$his allo&s us to calculate the remaining A;+sB for @une.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2E

5et, let us appl" the inventor" e#uation to the FR inventor" account.

)"@ A30$

Opening FR G22E,EEE 715-

) 'ost of goods manufactured D1D,EEE D:1,EEE

( 'ost of goods available for sale :HD,EEE :21,EEE

! 'ost of goods sold H1D,EEE 7499-

( 7nding FR inventor" 715- G22D,EEE

Once again, our computation uses the fact that the ending inventor" in /a" ( the

beginning inventor" in @une.

7.53

$his problem highlights the planning role for budgets. 8et us first determine the variable

and fied costs corresponding to 5aomi+s operations.

I5$< D$5"/# C3(($05 *'%5 E=9$*5$1 *'%5

>irect materials G1FE,EEEJ12E,EEE units G1Junit G1.1EJunit

>irect labor G:2E,EEEJ12E,EEE units GHJunit GH.3EJunit

2elling W Adm. G12E,EEEJG2.1 million DK of sales G DK of sales G

Fied costs GFFF,EEE GFFF,EEE

Cith this data in hand, let us prepare a pro-ected income statement if 5aomi raises her

price to G22 per unit.

Price = $22 & Number of units sold = 120,000

4evenues (12E,EEE units L G22) G2,H1E,EEE

Nariable costs

>irect materials GD2F,EEE

>irect labor :DH,EEE

2elling and administration 132,EEE G1,11H,EEE

'ontribution /argin G1,221,EEE

Fied costs

/anufacturing D1E,EEE

/arketing and sales 12E,EEE

Reneral administration 22F,EEE GFFF,EEE

P('&/5 2$&'($ 5"=$% 7336-

4eturn on sales

(G33H,EEEJG2,H1E,EEE) 12.:3K

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!21

8et us repeat the eercise &ith the lo&er!price, high!volume strateg".

Price = $19 & Number of units sold = 17,000

4evenues (1:D,EEE units L G1I) G3,32D,EEE

Nariable costs

>irect materials G::E,EEE

>irect labor 1,1E2,DEE

2elling and administration 1HH,2DE G2,E3F,:DE

'ontribution /argin G1,2FH,2DE

Fied costs

/anufacturing GD1E,EEE

/arketing and sales 12E,EEE

Reneral administration 22F,EEE GFFF,EEE

P('&/5 2$&'($ 5"=$% 7398-25

4eturn on sales

(G3IF,2DEJG3,32D,EEE) 11.IFK

.oth strategies meet 5aomi+s goals of increasing her profit and return on sales. =o&ever,

the t&o income statements conflict in terms of epected profit and epected profitabilit".

$he higher!price, lo&er volume strateg" has lo&er profit but higher profitabilit".

5aomi+s choice therefore depends on her goals and the nature of the product market. ,n

some instances, such as often occurs &ith premium products, it can make most sense to

go for a high margin strateg", sacrificing volume. ,n other instances, such as &ith

consumer goods, it might make more sense to lock up the market b" going for sales

gro&th. 4egardless, pro-ecting future income statements under alternate formats help

firms put a number on the tradeoff and make a more informed choice.

,n 5aomi+s case, she does not appear to have a sustainable competitive advantage for the

t"pes of products she offers (the barriers to entr" are likel" minimal) * thus, &e &ould

argue for setting a lo&er price and getting a larger share of the market.

7.54

$he participative budget described here seems participative in name onl". $he goal for

participative budgets is to take advantage of locali%ed kno&ledge that operating

personnel possess. ,n virtuall" ever" instance, the participative input is sub-ect to

oversight and discussion. 2ome amount of revision is also common. =o&ever, ecessive

and arbitrar" revie& that substitutes a top!do&n target for a bottom!up estimate makes a

mocker" of the process, eliminating its value. 2uch a gutting appears to be the case in

$im+s firm. /elanie+s statement hints at a ver" autocratic st"le that essentiall" sa"s, A/"

&a" or the high&a".B

$he revision process also appears to be arbitrar" and capricious. $here is little incentive

for the salespersons to spend much time and effort in pro-ecting the true epected sales

because the" kno& that the target &ould be revised up&ards and $im+s estimate &ill

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!22

prevail.

$his problem la"s the foundation for an interesting discussion about the costs and

benefits of participative budgeting. Chile these budgets are useful, the" also give rise to

game pla"ing and slack. 4evie&s b" top management cut do&n on slack, but also remove

some of the benefits. =o& best to manage the tradeoff is an open!ended problem &ith no

clear ans&er. 4esearch has identified factors that increase game pla"ing (ecessive

reliance on incentives, uncertain environment, lack of management eperience at the top,

lack of trust) but eecuting the tradeoff &ell remains an art.

7.55

a. $he follo&ing tables provide the re#uired classifications. $he classification into

manufacturing and selling depends is some&hat intuitive. $he classification into fied

versus variable costs is sub-ective to some degree. Ce gain confidence in this estimate

b" computing unit costs (for manufacturing epenses) and the cost per sales dollar

(for selling epenses) * if these costs sta" mostl" the same as volume changes, then

&e classif" the epense as variable. ,f, ho&ever, these costs decrease markedl" as

volume increases, then &e classif" the epense as fied.

)"03&"*53(/04 :);B

S$##/04 :S;

?/=$1 :?;B

V"(/"2#$ :V;

>irect materials ) V

>irect labor hours ) V

0lant maintenance ) ?

0lant depreciation ) ?

,ndirect labor ) V

7ngineering design ) ?

6tilities ) V

0lant administration ) ?

/arketing administration S ?

2ales force commissions S V

0lant supervision ) ?

.ased on the above &e conclude that3

(1) Nariable manufacturing costs >irect materials, direct labor, indirect labor, utilities

(2) Nariable selling costs 2ales commissions

(3) Fied manufacturing costs 0lant maintenance, plant depreciation, engineering

design, plant administration, and plant supervision

(1) Fied selling costs /arketing administration

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!23

b. 6sing the above table, &e obtain the follo&ing estimates (averages of three "ears)3

6nit price GDH.EEJunit

Nariable manufacturing costs G2:.H:Junit (the average for 3 months)

Nariable selling costs GE.E3 per sales G

$otal fied costs G2,1:F,EEE (the average for 3 months)

$hus, &e could &rite the firm+s contribution margin statement as follo&s3

6nits 1DE,EEE

4evenues GF,1EE,EEE

Nariable manufacturing costs 1,1DE,DEE

Nariable selling costs 2D2,EEE

'ontribution /argin G3,II:,DEE

$otal fied costs 2,1:F,EEE

P('&/5 2$&'($ 5"=$% 71-819-5

c. $his problem illustrates a A#uick and dirt"B &a" to budget operations. ,n essence, the

firm is using the 'N0 relation to pro-ect its goals for the coming "ear. $he parameters

for the 'N0 relation are the average of operations for the past three "ears. Chile this

approach has merit, there are potential concerns. First, given the significant change in

operations, it is likel" that the demand pro-ection falls outside the firm+s relevant

range of operations * thus, 7sse ma" need to add additional capacit" to manage the

additional demand. $he simple 'N0 relation ignores these complications. A second

ma-or problem is the omission of an" kind of detailed breakdo&n or basis for the

sales forecast * this is particularl" important given the optimistic nature of the

forecast * 7sse could find itself in an a&k&ard position if sales fall dramaticall"

short of pro-ections.

7.56

a. Cith the given data, &e could &rite the firm+s contribution margin statement as

follo&s3

O(/4/0"# A1C3%5<$05

R$6/%$1

B314$5

6nits 1DE,EEE 1DE,EEE

4evenues GF,1EE,EEE GF,1EE,EEE

Nariable manufacturing costs 1,1DE,DEE 1,1DE,DEE

Nariable selling costs 2D2,EEE 2D2,EEE

'ontribution /argin G3,II:,DEE G3,II:,DEE

$otal fied costs 2,1:F,EEE 7565-

1

G2,:13,EEE

P('&/5 2$&'($ 5"=$% 71-819-5 7565- 71-254-5

1

GDHD,EEE ( (22D,EEE ) 12D,EEE ) 1EE,EEE ) 1E,EEE ) :D,EEE).

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!21

5otice that &e have collapsed all of the increase in fied costs into one line item. $his

increase reflects the additional capacit" costs that stem from increasing the firm+s

production capabilities * as &e &ill learn in 'hapters I and 1E, cost allocations provide

us &ith a &a" to estimate such changes in capacit" costs.

b. Ce could pro-ect the income statement for 12D,EEE units, using the estimates for fied

and variable costs that &e derived for the previous problem. Ce have3

O(/4/0"# R$6$03$BC'%5 9$( 30/5

R$6/%$1

B314$5

6nits 1DE,EEE 125-

4evenues GF,1EE,EEE GDH.EE G:,EEE,EEE

Nariable manufacturing costs 1,1DE,DEE G2:.H: per unit 3,1DF,:DE

Nariable selling costs 2D2,EEE GE.E3 per sales G 21E,EEE

'ontribution /argin G3,II:,DEE G3,331,2DE

$otal fied costs 2,1:F,EEE 2,1:F,EEE

P('&/5 2$&'($ 5"=$% 71-819-5 71-153-25

5otice that 7sse+s profit decreases substantiall", b" 3:K, if the firm produces 12D,EEE

units.

c. .ased on our anal"sis, 7sse &ill more profitable situation if it produces 1DE,EEE

units and invests in additional capacit" resources. =o&ever, if the compan" decides to

go ahead and make the investment to meet the budgeted volume of 1DE,EEE and

demand falls short of epectations, either in the coming "ear or in future "ears, then

7sse &ill have to AeatB the additional fied costs. $his problem helps us see ho&

budgets enable firms to evaluate options in terms of their potential risks and re&ards.

7.57

$he follo&ing table provides the re#uired income statement.

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4 T'5"#

2ales G1EH,EEE GD2I,2DE G12E,DEE GDI1,DEE G1,IDE,2DE

>iscounts

1

D2,I2D DI,1DE 112,3:D

5et 2ales G1EH,EEE G1:H,32D G12E,DEE GD3D,EDE G1,F3:,F:D

'ost of merchandise

2

2FE,EEE 3HD,EEE 2IE,EEE 11E,EEE 1,31D,EEE

'redit card fees

3

H,1IH :,H21 H,:2F F,DH1 2I,1EH

Fied costs

1

1ED,EEE 1ED,EEE 1ED,EEE 1ED,EEE 12E,EEE

P('&/5 714-54 :71-296; 718-772 711-489 743-469

5otes3

1. >iscounts ( "ale L .DE L .2E in Vuarters 2 and 1.

2. 'ost of merchandise ( 2alesJ1.1D.

3. 'redit card fees ( .E2 L .FE L Net "ale.

1. Fied costs ( G3D,EEE L 3 months per #uarter.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2D

7.58

a. $he follo&ing table provides the re#uired monthl" budget.

I5$< D$5"/# A<'305

2ubscription fees

.asic 'able DE,EEE L E.ED L G2E GDE,EEE

7tended .asic DE,EEE L E.ID L GDE 2,3:D,EEE

0remium 'hannels 1D,EEE L G1E 1DE,EEE

,nternet connection 2H,EEE L G1D 1,1:E,EEE

/odem fees 2E,EEE L G3 HE,EEE

$otal subscriptions G3,FED,EEE

>iscounts

0remium channels 1,EEE L G(2EKM1E) F,EEE

.undling 2D,DEE L GD 12:,DEE

5et 4evenues G3,HHI,DEE

'ontent fees Fied G1,1EE,EEE

'ontent fee (0remium) 1D,EEE L GH IE,EEE

Franchise fee (2pudcit") 1EK L 5et 4evenues 3HH,IDE

,nternet fee 2H,EEE L G3D I1E,EEE

,nternet fee Fied FD,EEE

Operating costs

,nstallation 2DE S GHE 1D,EEE

4epair HEE S G3D 21,EEE

8ine maintenance 3D S G:D 2,H2D

Operating costs Fied 1DE,EEE

$otal costs G3,31E,D:D

P('&/5 2$&'($ T"=$% 7328-925

b. $here are man" similarities in the process. One similarit" includes the focus on output

activit" (number of subscribers) for the firm+s various products ($N, 0remium

channels, ,nternet) as the starting point. $his estimate serves as the basis for both

revenues and costs (e.g., franchise fees). @ust like a manufacturing firm, the service

firm has both variable and fied costs.

$here are a fe& differences, though. For eample, there is not much room for a

production or purchases budget for /edia /ogul. $he primar" service is to act as a pass

through agent bet&een the $N content providers and the retail customer. Other than this

difference in orientation, &e &ould argue that the budgeting process is more alike than

not.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2H

7.59

5ot!for!profit organi%ations, &hich often operate multiple programs, face uni#ue

planning, control, and reporting needs.

From the output side, ,!'are needs to track budgets and actual results b" program so that

it could assess the effectiveness of individual activities.

From the input side, ,!'are also might need to track epenses and activities b" specific

grants. For eample, suppose 62A,> gives ,!'are a grant of G1,EEE,EEE. ,!'are &ould

need to submit periodic reports that sho& ho& it used these funds. Often, the mone" ma"

be spent for multiple programs, &hich complicates the reporting process.

From a regulator" vie& point, ,!'are needs to submit reports to the ,42 and other

agencies (e.g., Form IIE). $hese forms have specific epense categories such as fund

raising epenses.

From a control perspective, a significant amount of cost is common across programs.

2uch costs often pertain to personnel because the same set of people might &ork on

several programs simultaneousl". Of course, ,!'are also needs to have appropriate

epense approval and reporting policies in place because of the significant fiduciar"

responsibilit" it bears to&ards donors. Often, charities &ill voluntaril" undergo annual

audits (b" suitabl" #ualified accountants) to increase confidence among donors.

$hus, &e see that not!for!profit institutions such as ,!'are re#uire sophisticated budgeting

and control s"stems to meet their various information needs. 6suall", such organi%ations

prepare a program!centered budget, &herein the" estimate costs for each of the man"

programs the" might eecute during a "ear. ,n addition, the organi%ation needs to budget

for common activities such as a fund!raising campaign or office administration.

Riven the number of eternal constituents, the budgeting process at ,!'are t"picall"

&ould be more detailed and involved than the process for a for!profit organi%ation (&hose

primar" goal is to make mone"). ,ndeed, for each program, ,!'are needs to estimate the

activit" volume and associated costs. /oreover, each program might comprise several

modules (such as the number of senior centers visited, &ith each visit being a module)

that might be scaled up or do&n based on the availabilit" of funds and actual epenses.

6suall", accounting s"stems in such organi%ations allo& the data to be aggregated along

multiple dimensions. For eample, an" specific ependiture &ould be classified as to

program ('orneal transplant), source of funds (Taufman Foundation grant Q11!DH:!

2EED), and functional categor" ($ravel3 Airfare).

Overall, this problem looks at ho& budgeting needs might s"stematicall" differ across

organi%ations.

7.6

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2:

$o prepare an income statement, &e need to be able to calculate the cost of goods sold

('OR2). $his is the outflo& from the finished goods (FR) inventor" account. =o&ever,

&e do not have the inflo& into the FR account.

For 0eterson, the inflo&s into the FR account comprise materials and labor (because all

overhead epenses are fied). Once again, &hile &e kno& labor costs, &e do not kno&

the materials used in production. =o&ever, &e do have information about the amount of

materials purchased and epected inventories.

$hus, &e can back out the materials issued, as sho&n belo&3

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4

Opening balance for materials

G1EE,EEE G12E,EEE G11D,EEE G12D,EEE

) 0urchases

23D,EEE 211,2EE 222,3EE 2E:,DEE

( $otal available

GH3D,EEE GH31,2EE GH3:,3EE GH32,DEE

! 7nding balance

12E,EEE 11D,EEE 12D,EEE 11E,EEE

( /aterials used for production

G21D,EEE G21H,2EE G212,3EE G222,DEE

,n this table, notice that &e link #uarters b" the fact that ending inventor" in V1 (

beginning inventor" in V2. 8et us no& compute 0eterson+s 'OR/.

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4

/aterials used for production

G21D,EEE G21H,2EE G212,3EE G222,DEE

) >irect labor

21E,EEE 211,DEE 23F,DEE 21F,HEE

( 'ost of goods manufactured

G1DD,EEE G1HE,:EE G1DE,FEE G1:1,1EE

5et, &e use the inventor" e#uation for the FR inventor" to determine 'OR2.

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4

Opening balance

G3FE,EEE G3IE,1EE G3FD,HEE G3I1,2DE

) 'ost of goods manufactured

1DD,EEE 1HE,:EE 1DE,FEE 1:1,1EE

( $otal available

GF3D,EEE GFD1,1EE GF3H,1EE GFH2,3DE

! 7nding balance

3IE,1EE 3FD,HEE 3I1,2DE 3IH,DEE

( 'ost of goods sold

G111,HEE G1HD,DEE G11D,1DE G1HD,FDE

Again, notice that ending balance in V1 ( opening balance in V2.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2F

Ce are finall" read" to prepare the 0eterson+s contribution margin income statement.

Q3"(5$( 1 Q3"(5$( 2 Q3"(5$( 3 Q3"(5$( 4

4evenue

G:ID,2EE GF31,2EE GFH1,1DE GFDH,2DE

! Nariable cost of goods sold

111,HEE 1HD,DEE 11D,1DE 1HD,FDE

( 'ontribution margin

G3DE,HEE G3HF,:EE G11I,3EE G3IE,1EE

! Fied manufacturing costs

1DE,EEE 1:2,2DE 1HI,2DE 1:1,3EE

! Fied selling epenses

FE,EEE ID,EEE 1EH,EEE 1EE,EEE

( 0rofit before taes

712-6 711-45 7144-5 7116-1

7.61

8et us begin b" first constructing 0eterson+s budgeted cash collections. Ce have3

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

Opening

receivables

balance G12D,EEE G1EH,E2: G111,22: G11D,2HE

) 2ales :ID,2EE F31,2EE FH1,1DE FDH,2DE

( $otal collectible GI2E,2EE GI1E,22: GI:D,H:: GI:1,D1E

D C'##$*5/'0% 814-173 829- 86-417 857-343

( 7nding balance G1EH,E2: G111,22: G11D,2HE G111,1H:

5otice that collections include all of the opening balance. $he" also include all sales for

the first t&o months of the #uarter and HEK for the third month. Alternativel", &e

compute the ending balance as 1EK of the last month+s sales (all else &ould have been

collected) and back out the collections.

5et, &e compute the cash outflo& for purchases.

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

Opening pa"ables

balance G12H,DEE G3I,1H: G3D,2EE G3:,EDE

) 0urchases 23D,EEE 211,2EE 222,3EE 2E:,DEE

( $otal 0a"able G3H1,DEE G2DE,3H: G2D:,DEE G211,DDE

D P"@<$05% 322-333 215-167 22-45 29-967

( 7nding balance G3I,1H: G3D,2EE G3:,EDE G31,DF3

As &ith collections, pa"ments include all of the opening balance. $he" also include all

purchases for the first t&o months of the #uarter and DEK for the third month.

Alternativel", &e compute the ending balance as DEK of the last month+s purchases

(0eterson+s &ould have paid all other bills.)

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!2I

Cith these estimates in hand, &e are no& read" to construct the overall cash budget.

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

Opening balance G:D,EEE 111,F1E G22F,I23 G3:E,11E

) 'ollections 814-173 829- 86-417 857-343

( $otal available GFFI,1:3 GI1E,F1E G1,EFI,31E G1,22:,1F3

0a"ments for purchases 322,333 21D,1H: 22E,1DE 2EI,IH:

8abor costs 21E,EEE 211,DEE 23F,DEE 21F,HEE

Fied manufacturing costs 13D,EEE 1D:,2DE 1D1,2DE 1DI,3EE

Fied selling costs FE,EEE ID,EEE 1EH,EEE 1EE,EEE

, E01/04 2"#"0*$ 7111-84 7228-923 737-14 759-616

,n our computations, notice that &e have removed G1D,EEE each #uarter for non!cash

manufacturing overhead epenses.

5otice that the cash balance is gro&ing &hile income (see the prior problem) sta"s

relativel" stable over the four #uarters. Ch" is this; $his occurs because &e assumed that

0eterson hoards all of its cash * thus, the cash balance increases each #uarter b" the

amount of income (there also is a G1D,EEE difference due to the non!cash overhead

epense, &hich is accounted for in the income statement but not in the cash budget). ,n

realit", 0eterson &ould not maintain such a large cash balance but &ould reinvest the

proceeds back in its o&n business or else&here.

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!3E

)INI CASES

7.62 $his is a fairl" involved problem, best done on a spreadsheet. Ce follo& the same

template as in the tet. Ce begin &ith 0umpkin 0atch+s revenue budget3

a.(see ehibits beginning net page)

.alakrishnan, /anagerial Accounting 1e FO4 ,52$46'$O4 627 O589

:!31

E=+/2/5 1

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > R$6$03$ B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r 'ctober No(ember

#ecembe

r $otal

S5"01"(1

2ales in units 1E,EEE 11,1EE 12,EEE 1D,HEE 1F,EEE 22,EEE FI,EEE

0rice per unit G1: G1: G 1: G1: G1: G1: G1:

4evenues G1:E,EEE G1I3,FEE G 2E1,EEE G2HD,2EE G3EH,EEE G3:1,EEE G 1,D13,EEE

D$#3=$

2ales in units 3,DEE 1,EEE 1,DEE D,EEE D,DEE H,EEE 2F,DEE

0rice per unit G2H G2H G 2H G2H G2H G2H G2H

4evenues GI1,EEE G1E1,EEE G 11:,EEE G13E,EEE G113,EEE G1DH,EEE G:11,EEE

$otal 4evenues G2H1,EEE G2I:,FEE G 321,EEE G3ID,2EE G11I,EEE GD3E,EEE G 2,2D1,EEE

:.32

:!32

Ce net prepare 0umpkin 0atch+s production budget3

E=+/2/5 2

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > P('13*5/'0 B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r

'ctobe

r No(ember

#ecembe

r

S5"01"(1

2ales in units (see 7hibit 1) 1E,EEE 11,1EE 12,EEE 1D,HEE 1F,EEE 22,EEE

) >esired ending inventor" +Note ,- 2,FDE 3,EEE 3,IEE 1,DEE D,DEE 1,DEE

( $otal re#uirements 12,FDE 11,1EE 1D,IEE 2E,1EE 23,DEE 2H,DEE

! .eginning inventor" +Note .- 2,DEE 2,FDE 3,EEE 3,IEE 1,DEE D,DEE

( 6nits to be produced 1E,3DE 11,DDE 12,IEE 1H,2EE 1I,EEE 21,EEE

D$#3=$

2ales in units (see 7hibit 1) 3,DEE 1,EEE 1,DEE D,EEE D,DEE H,EEE

) >esired ending inventor" +Note ,- 1,EEE 1,12D 1,2DE 1,3:D 1,DEE 1,EDE

( $otal re#uirements 1,DEE D,12D D,:DE H,3:D :,EEE :,EDE

! .eginning inventor" +Note .- F:D 1,EEE 1,12D 1,2DE 1,3:D 1,DEE

( 6nits to be produced 3,H2D 1,12D 1,H2D D,12D D,H2D D,DDE

+Note ,-/ >esired ending inventor" e#uals 2DK of the follo&ing month+s forecasted sales volume in

units. >esired ending inventories for @anuar", 2EEI are 1,EEE standard units and 1,EEE delue units, as

stipulated in the problem tet.

+Note .-3 $he beginning inventor" for @ul" is the desired ending inventor" of @une, &hich e#uals 2DK of

the @ul" forecast.

:.33

:!33

5et, &e prepare the materials usage budget3

E=+/2/5 3

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > D/($*5 )"5$(/"#% U%"4$ B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r

'ctobe

r No(ember

#ecembe

r

S5"01"(1

6nits of production (see 7hibit 2) 1E,3DE 11,DDE 12,IEE 1H,2EE 1I,EEE 21,EEE

0lastic (( units of production L 1

pound per set L G3 per pound) G31,EDE G31,HDE G3F,:EE G1F,HEE GD:,EEE G H3,EEE

Other materials (( units of

production L G1) 1E,3DE 11,DDE 12,IEE 1H,2EE 1I,EEE 21,EEE

2tandard materials cost G11,1EE G1H,2EE GD1,HEE GH1,FEE G:H,EEE G F1,EEE

D$#3=$

6nits of production (see 7hibit 2) 3,H2D 1,12D 1,H2D D,12D D,H2D D,DDE

0lastic (( units of production L 1.DE

pounds per set L G3 per pound) G1H,313

G1F,DH

3 G2E,F13

G23,EH

3 G2D,313 G21,I:D

Other materials (( units of

production L G1.2D) 1,D31 D,1DH D,:F1 H,1EH :,E31 H,I3F

>elue materials cost G2E,F11 G23,:1I G2H,DI1 G2I,1HI G32,311 G31,I13

B'5+ P('13*5%

$otal units of production 13,I:D 1D,H:D 1:,D2D 21,32D 21,H2D 2H,DDE

$otal plastic G1:,3H3 GD3,213 GDI,D13 G:1,HH3 GF2,313 GF:,I:D

$otal other materials G11,FF1 G1H,:EH G1F,HF1 G22,HEH G2H,E31 G2:,I3F

$otal materials cost GH2,211 GHI,I1I G:F,1I1 GI1,2HI G1EF,311 G11D,I13

:.31

:!31

For direct labor costs, &e have3

E=+/2/5 4

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > D/($*5 L"2'( B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r 'ctober No(ember

#ecembe

r

S5"01"(1

6nits of production (see 7hibit 2) 1E,3DE 11,DDE 12,IEE 1H,2EE 1I,EEE 21,EEE

8abor hours per unit E.DE E.DE E.DE E.DE E.DE E.DE

8abor cost per hour G1H G1H G 1H G1H G1H G1H

>irect labor cost GF2,FEE GI2,1EE G 1E3,2EE G12I,HEE G1D2,EEE G1HF,EEE

D$#3=$

6nits of production (see 7hibit 2) 3,H2D 1,12D 1,H2D D,12D D,H2D D,DDE

8abor hours per unit E.:D E.:D E.:D E.:D E.:D E.:D

8abor cost per hour G1H G1H G 1H G1H G1H G1H

>irect labor cost G13,DEE G1I,DEE GDD,DEE GH1,DEE GH:,DEE GHH,HEE

$otal labor cost G12H,3EE G111,IEE G1DF,:EE G1I1,1EE G21I,DEE G231,HEE

$he third component is manufacturing overhead costs3

E=+/2/5 5

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > )"03&"*53(/04 O6$(+$"1 B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r

'ctobe

r No(ember

#ecembe

r

V"(/"2#$ )"03&"*53(/04 O6$(+$"1 E E E E E E

?/=$1 )"03&"*53(/04 O6$(+$"1

'ash epenses G2H,EEE G2H,EEE G2H,EEE G2H,EEE G2H,EEE G2H,EEE

>epreciation and other non!cash epenses G22,EEE G22,EEE G22,EEE G22,EEE G22,EEE G22,EEE

$otal fied overhead G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE

:.3D

:!3D

$otal /anufacturing Overhead G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G 1F,EEE G 1F,EEE

Ce net compute the variable cost of goods manufactured3

E=+/2/5 6

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > V"(/"2#$ C'%5 '& G''1% )"03&"*53($1

From

7hibit *ul% !ugut "eptember 'ctober No(ember #ecember

S5"01"(1

0lastic 3 G31,EDE G31,HDE G3F,:EE G1F,HEE GD:,EEE GH3,EEE

Other materials 3 1E,3DE 11,DDE 12,IEE 1H,2EE 1I,EEE 21,EEE

>irect manufacturing labor 1 F2,FEE I2,1EE 1E3,2EE 12I,HEE 1D2,EEE 1HF,EEE

2tandard cost of goods manufactured G121,2EE G13F,HEE G1D1,FEE G1I1,1EE G 22F,EEE G2D2,EEE

D$#3=$

0lastic 3 G1H,313 G1F,DH3 G2E,F13 G23,EH3 G2D,313 G21,I:D

Other /aterials 3 1,D31 D,1DH D,:F1 H,1EH :,E31 H,I3F

>irect /anufacturing 8abor 1 13,DEE 1I,DEE DD,DEE H1,DEE H:,DEE HH,HEE

>elue cost of goods manufactured GH1,311 G:3,21I GF2,EI1 GIE,IHI GII,F11 GIF,D13

$otal variable cost of goods manufactured G1FF,D11 G211,F1I G23H,FI1 G2FD,3HI G32:,F11 G3DE,D13

:.3H

:!3H

As goods manufactured flo& through the FR inventor" account, let us eamine the cost flo& through the FR inventor" account as &ell.

E=+/2/5 7

C'%5 '& ?/0/%+$1 G''1% I06$05'(@ "% '& A30$ 3- 28

"tandard #elu0e

Nariable cost per unit +gi(en- G12.EE G1:.EE

C'%5 '& ?/0/%+$1 G''1% I06$05'(@ "% '& A3#@ 31- 28

"tandard #elu0e

V"(/"2#$ C'%5 9$( U0/5

0lastic G3.EE G1.DE

Other materials 1.EE 1.2D

>irect labor F.EE 12.EE

$otal G12.EE G1:.:D

C'%5 '& B$4/00/04 "01 E01/04 ?/0/%+$1 G''1% I06$05'(@ :2"%$1 '0 ?I?O /06$05'(@ "**'305/04;

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r

'ctobe

r No(ember

#ecembe

r

S5"01"(1

.eginning inventor" in units 2,DEE 2,FDE 3,EEE 3,IEE 1,DEE D,DEE

Nariable cost per unit G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE

.eginning inventor" cost G3E,EEE G31,2EE G3H,EEE G1H,FEE GD1,EEE GHH,EEE

7nding inventor" in units 2,FDE 3,EEE 3,IEE 1,DEE D,DEE 1,DEE

Nariable cost per unit G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE G12.EE

7nding inventor" cost G31,2EE G3H,EEE G1H,FEE GD1,EEE GHH,EEE GD1,EEE

D$#3=$

.eginning inventor" in units F:D 1,EEE 1,12D 1,2DE 1,3:D 1,DEE

Nariable cost per unit G1:.EE G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D

.eginning inventor" cost G11,F:D G1:,:DE G1I,IHI G22,1FF G21,1EH G2H,H2D

7nding inventor" in units 1,EEE 1,12D 1,2DE 1,3:D 1,DEE 1,EDE

Nariable cost per unit G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D G1:.:D

:.3:

:!3:

7nding inventor" cost G1:,:DE G1I,IHI G 22,1FF G21,1EH G 2H,H2D G1F,H3F

:.3F

:!3F

Ce are no& read" to compute the variable cost of goods sold.

E=+/2/5 8

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > C'%5 '& G''1% S'#1 B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r 'ctober No(ember

#ecembe

r

S5"01"(1

.eginning Finished Roods ,nventor" (see 7hibit :) G3E,EEE G31,2EE G3H,EEE G1H,FEE GD1,EEE GHH,EEE

) 'ost of Roods /anufactured (see 7hibit H) 121,2EE 13F,HEE 1D1,FEE 1I1,1EE 22F,EEE 2D2,EEE

( 'ost of Roods Available for 2ale G1D1,2EE

G1:2,FE

E G1IE,FEE

G211,2E

E G2F2,EEE G31F,EEE

! 7nding Finished Roods ,nventor" (see 7hibit :) 31,2EE 3H,EEE 1H,FEE D1,EEE HH,EEE D1,EEE

( Nariable 'ost of Roods 2old G12E,EEE G13H,FEE G111,EEE

G1F:,2E

E G21H,EEE G2H1,EEE

D$#3=$

.eginning Finished Roods ,nventor" (see 7hibit :) G11,F:D G1:,:DE G1I,IHI G22,1FF G21,1EH G2H,H2D

) 'ost of Roods /anufactured (see 7hibit H) H1,311 :3,21I F2,EI1 IE,IHI II,F11 IF,D13

( 'ost of Roods Available for 2ale G:I,21I GIE,IHI G1E2,EH3 G113,1D: G121,2DE G12D,13F

! 7nding Finished Roods ,nventor" (see 7hibit :)

1:,:

DE

1I,

IHI

22,1F

F

21,1E

H 2H,H2D 1F,H3F

( Nariable 'ost of Roods 2old GH1,1HI G:1,EEE G:I,F:D GFF,:DE GI:,H2D G1EH,DEE

:.3I

:!3I

8et us finish the final piece, marketing and administrative epenses.

E=+/2/5 9

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > )"(E$5/04 "01 A1</0/%5("5/6$ C'%5% B314$5

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r 'ctober No(ember

#ecembe

r

Nariable /arketing and Administrative 'osts

S5"01"(1

4evenues (see 7hibit 1) G1:E,EEE G1I3,FEE G 2E1,EEE G2HD,2EE G3EH,EEE G3:1,EEE

'ommissions (HK of revenues) 1E,2EE 11,H2F 12,21E 1D,I12 1F,3HE 22,11E

Other (1K of revenues) H,FEE :,:D2 F,1HE 1E,HEF 12,21E 11,IHE

Nariable 'osts G1:,EEE G1I,3FE G2E,1EE G2H,D2E G3E,HEE G3:,1EE

D$#3=$

4evenues (see 7hibit 1) GI1,EEE

G1E1,EE

E G 11:,EEE

G13E,EE

E G113,EEE G1DH,EEE

'ommissions (HK of revenues) D,1HE H,21E :,E2E :,FEE F,DFE I,3HE

Other (1K of revenues) 3,H1E 1,1HE 1,HFE D,2EE D,:2E H,21E

Nariable 'osts GI,1EE G1E,1EE G11,:EE G13,EEE G11,3EE G1D,HEE

$otal Nariable /arketing and

Administrative 'osts G2H,1EE G2I,:FE G32,1EE G3I,D2E G11,IEE GD3,EEE

Fied /arketing and Administrative 'osts

2alaries and &ages G3,EEE G3,EEE G3,EEE G3,EEE G3,EEE G3,EEE

4ent :,EEE :,EEE :,EEE :,EEE :,EEE :,EEE

>epreciation (non!cash) 1,DEE 1,DEE 1,DEE 1,DEE 1,DEE 1,DEE

$otal Fied /arketing and G11,DEE G11,DEE G11,DEE G11,DEE G11,DEE G11,DEE

:.1E

:!1E

Administrative 'osts

:.11

:!11

Cith all of the data in hand, &e can construct the income statement, as follo&s.

P3<9E/0 P"5*+ > B314$5$1 I0*'<$ S5"5$<$05

*ul% !ugut

"eptembe

r 'ctober

No(embe

r

#ecembe

r 1otal

4evenues (see 7hibit 1) G2H1,EEE G2I:,FEE G321,EEE G3ID,2EE G11I,EEE GD3E,EEE G2,2D1,EEE

Nariable 'osts

/anufacturing (see 7hibit F) 1F1,1HI 2E:,FEE 223,F:D 2:D,IDE 313,H2D 3:E,DEE 1,D:3,21I

/arketing W Admin (see 7hibit I) 2H,1EE 2I,:FE 32,1EE 3I,D2E 11,IEE D3,EEE 22D,1EE

$otal 'ontribution /argin GD3,131 GHE,22E GHD,E2D G:I,:3E GIE,1:D G1EH,DEE G1DD,3F1

Fied 'osts

/anufacturing (see 7hibit D) G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G1F,EEE G2FF,EEE

/arketing W Admin (see 7hibit I) 11,DEE 11,DEE 11,DEE 11,DEE 11,DEE 11,DEE HI,EEE

$otal Fied 'osts GDI,DEE GDI,DEE GDI,DEE GDI,DEE GDI,DEE GDI,DEE G3D:,EEE