Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income Growth For The Poor in Rural Pakistan

Uploaded by

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) Ltd0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views18 pagesIn spite of substantial growth in agricultural real GDP in the 1990s, however, rural poverty did not decline. Instead, the percentage of poor was essentially unchanged between 1990-91 and 1998-99 and may have risen slightly by 2001 Several factors help explain the stagnation in rural poverty in the 1990s in spite of substantial agricultural growth, including overestimates of livestock income growth, a rise in the real consumer price of major staples, and the skewed distribution of returns to land coupled with a declining share of the crop sector in overall GDP (Malik, 2005; Dorosh, Niazi, and Nazli, 2003). This study explores these questions related to agricultural growth and rural poverty using household panel data and secondary data sources to examine income dynamics in four districts of Pakistan from the late 1980s to 2002.

Original Title

Transitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income Growth for the Poor in Rural Pakistan

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn spite of substantial growth in agricultural real GDP in the 1990s, however, rural poverty did not decline. Instead, the percentage of poor was essentially unchanged between 1990-91 and 1998-99 and may have risen slightly by 2001 Several factors help explain the stagnation in rural poverty in the 1990s in spite of substantial agricultural growth, including overestimates of livestock income growth, a rise in the real consumer price of major staples, and the skewed distribution of returns to land coupled with a declining share of the crop sector in overall GDP (Malik, 2005; Dorosh, Niazi, and Nazli, 2003). This study explores these questions related to agricultural growth and rural poverty using household panel data and secondary data sources to examine income dynamics in four districts of Pakistan from the late 1980s to 2002.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views18 pagesTransitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income Growth For The Poor in Rural Pakistan

Uploaded by

Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdIn spite of substantial growth in agricultural real GDP in the 1990s, however, rural poverty did not decline. Instead, the percentage of poor was essentially unchanged between 1990-91 and 1998-99 and may have risen slightly by 2001 Several factors help explain the stagnation in rural poverty in the 1990s in spite of substantial agricultural growth, including overestimates of livestock income growth, a rise in the real consumer price of major staples, and the skewed distribution of returns to land coupled with a declining share of the crop sector in overall GDP (Malik, 2005; Dorosh, Niazi, and Nazli, 2003). This study explores these questions related to agricultural growth and rural poverty using household panel data and secondary data sources to examine income dynamics in four districts of Pakistan from the late 1980s to 2002.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 18

Transitions Out of Poverty: Drivers of Real Income

Growth for the Poor in Rural Pakistan

Paul A. DOROSH

Sohail J. MALIK

Contributed paper prepared for presentation at the

International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference,

Gold Coast, Australia, August 12-18, 2006

Copyright 2006 by Paul A. DOROSH and Sohail J. MALIK. All rights reserved. Readers

may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means,

provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies.

Transitions Out of Poverty:

Drivers of Real Income Growth for the Poor in Rural Pakistan

1

Paul A. Dorosh*

and

Sohail J. Malik**

* Senior Rural Development Economist, World Bank (pdorosh@worldbank.org).

** Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, Professor of Economics, University of Sargodha, Pakistan.

1

We wish to thank Kelly Jones and Hina Nazli for their assistance with the statistical analysis presented in

this paper. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and are not meant to represent

the views of their respective institutions.

2

Transitions Out of Poverty:

Drivers of Real Income Growth for the Poor in Rural Pakistan

Paul A. Dorosh and Sohail J. Malik

I. Introduction

In the 1980s, rapid growth in agricultural GDP of 3.9 percent contributed to a

steady decline in rural poverty from 49.3 percent in 1984-85 to 36.9 percent in 1990-91.

In spite of substantial growth in agricultural real GDP in the 1990s (4.6 percent),

however, rural poverty did not decline. Instead, the percentage of poor was essentially

unchanged between 1990-91 (36.9 percent) and 1998-99 (35.9 percent), and may have

risen slightly by 2001 to 38.9 percent.

2

Several factors help explain the stagnation in rural poverty in the 1990s in spite of

substantial agricultural growth, including overestimates of livestock income growth, a

rise in the real consumer price of major staples, and the skewed distribution of returns to

land coupled with a declining share of the crop sector in overall GDP (Malik, 2005;

Dorosh, Niazi, and Nazli, 2003).

This study explores these questions related to agricultural growth and rural

poverty using household panel data and secondary data sources to examine income

dynamics in four districts of Pakistan from the late 1980s to 2002. Section 2 of this paper

describes the sample and presents both primary and secondary data on the economic

structure and infrastructure of the selected districts. Following earlier work on poverty

transitions in Pakistan for a subset of the panel through 1992 (McCullough and Baulch,

2

There remains considerable debate surrounding the 2001-02 poverty figures and the poverty lines used,

however, and recent government figures for this year show a povert y decline. The figures in the text are

from World Bank (2002), p. 20 and Government of Pakistan (2003), Pakistan Economic Survey, 2002-03).

3

2000) and in Bangladesh (Sen, 2003), section 3 includes compute poverty transition

matrices over the period, and examines sources of income for poor households.

Regressions on the determinants of household welfare, incorporating data on levels of

infrastructure across villages and over time, are discussed in section 4. The last section

presents conclusions and policy implications.

II. Economic Structure of the Sample Districts

Economic structure of the districts included in this sample varies substantially

(Table 1).

3

Attock and Lower Dir in northern Pakistan and Badin on the southern coast

of Pakistan are primarily rural districts, with total populations of 0.7 to 1.3 million and

only 6 to 21 percent urbanization rates. By contrast, Faisalabad district in north-central

Pakistan, with a similar area to Attock and Badin, has a population of 5.4 million, a major

industrial (textile) city (also named Faisalabad), and is 57 percent urban. Only one-

quarter of the labor force in Faisalabad is employed in agriculture as a primary

occupation, compared to 80 percent in Badin. Even in predominantly rural Attock and

Dir, however, less than half of the labor force has agriculture as a primary occupation.

Agricultural land distribution and production also vary considerably, reflecting

both agro-ecology and historical patterns of land accumulation. Most of agriculture in

Faisalabad, as in most of the Indus basin of Pakistan is irrigated by canals, along with

supplemental tubewell irrigation. Sixty percent of farms are 5 to 25 acres in size (2.0 to

10.1 hectares) and 91 percent are less than 25 acres in size. Wheat, the major staple of

Pakistan, accounts for 37 percent of area cultivated in the district, but sugarcane and to a

3

Three of the four districts included in this study, Attock in Punjab province, Badin in Sindh province and

Lower Dir in Northwest Frontier province (NWFP) were originally selected because they were among the

poorest districts in Pakistan. The fourth distsrict, Faisalabad in Punjab province, was selected as a control

to represent a higher income district. See Alderman and Garcia (1993).

4

lesser extent, cotton are also major crops. Rice and sugar cane dominate cropping

patterns in Badin, where large farms dominate: farms larger than 50 acres (20 hectares)

account for about one-third of area cultivated. Most agriculture in Attock and Lower Dir

is rainfed, and wheat accounts for one-half of area cultivated in Attock and three-fourths

of area cultivated in lower Dir.

There have been major changes in infrastructure in these districts between 1980

and 1998, the years of the last two national population censuses in Pakistan (Table 2).

The percentage of households with electricity according increased from 42 to 61 percent

in Faisalabad, 17 to 49 percent in lower Dir and 22 to 35 percent in Badin (no data for

1980 is available for Attock). Similar large gains were observed for piped water, though

even by 1998 only 13 to 33 percent of households in these four districts had access to

piped water. Less than half of households had latrines in 1998 in these districts except

for the more-highly urbanized Faisalabad.

Considering only villages included in the household survey sample, almost all

were electrified in 1988, except in Badin, where only 2 of the 19 villages had electricity

in that year. By 2001, 10 of the 19 villages in the Badin sample had been electrified.

There were major improvements in the number of villages with paved roads in Attock,

Faisalabad and Badin, as well. Almost none of the villages had public drainage in either

1988 or 2001.

5

III. Household incomes and poverty transitions

The household data set used in this analysis is made up of 14 rounds of the

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) sample from 1986/87 to 1990/91,

together with a sub-sample of panel data households included in the 2001/02 Pakistan

Rural Household Survey (PRHS). The 571 household sample used in the analysis

includes only the base households. Households that have split off from the base

household are not included in this analysis.

Note also that 103 households that had data for all five years of the IFPRI survey

could not be traced after 11 years. On average, these households were poorer than the

average household that could be traced: 24 percent lower real incomes per adult

equivalent (Rs (2002) 11,756 compared with 13,842) and 39 percent lower value of

household assets (Rs (2002) 160, 314 compared with 264,144).

Table 3 presents data on the composition of average real incomes for the 1986/87

91/92 period by district, as well as the percentage change in 2002. The use of average

real incomes in the first five year period is designed to provide a measure of medium-

term incomes that smooths out transitory fluctuations in real incomes due to changes in

crop output, prices and other factors from year to year (McCullough and Baulch, 2000).

Unfortunately, there is only a single observation per household for 2002, a year of poor

rainfall in much of Pakistan.

For the sample as a whole, real incomes per adult equivalent declined by 13.1

percent between the first and second periods, with most of the decline attributable to a

decline in non-farm incomes and remittances. Non- farm incomes accounted for 33

percent of total incomes in the first period, and fell by 30.2 percent in real terms in 2002.

6

Remittances (both domestic and foreign), which accounted for only 13.2 percent of real

incomes in the first period, fell by almost half (49.4 percent). Net crop profits (25.4

percent of incomes in the first period) rose on average by 37.8 percent, though these

gains were partially offset by a decline in livestock incomes (13.9 percent of real incomes

in the first period) of 18.3 percent.

There were sharp differences in both the structure of incomes and the changes

across district, however. For the sample households, average real incomes per adult

equivalent rose moderately between the 1986/87 91/92 average and 2002 in Faisalabad

(11.7 percent) and Attock (9.2 percent) the two districts in Punjab province. In contrast,

real incomes fell in Badin (-15.7 percent) and Dir (-60.5 percent). Large declines in non-

farm income in Badin (-58.8 percent) and Dir (-67.3 percent), compared with only small

changes in Faisalabad (1.4 percent) and Attock (-8.1 percent), explain much of these

patterns in changes in real incomes across districts. These latter two districts are also the

two districts with highest growth in net crop profits; (net crop profits actually fell sharply

in Dir). The decline in remittance earnings for households in Faisalabad, Badin and Dir

mirrors an overall decline in remittances from workers in the Middle East during this

period. Remittance earnings actually rose slightly in Attock, though these earnings were

mainly domestic earnings, largely from jobs in nearby Islamabad and Rawalpindi.

Poor households (defined as the bottom 40 percent of households in terms of

average real income from 1987 to 1991 fared better on average than did non-poor

households, in terms of percentage gains in real incomes (Table 4). Crop incomes rose

faster (80.7 percent compared with 34.5 percent) for poor than for non-poor households.

Non-farm incomes also fell by less (-15.7 percent compared with -39.6 percent). Finally,

7

remittance earnings actually rose for poor households (by 2.5 percent), but fell by 62.5

percent for non-poor households, as households that had received substantial foreign

remittances in the first period were generally among the non-poor.

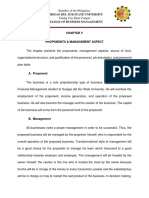

Figure 1 shows the rural poverty transitions over time, (again defining poverty as

the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution for the 1987 to 1991 period). Several

points can be noted. First, there was substantial movement in and out of poverty in the

first period (1986/87 to 1990/91). Although poverty rates tended to rise slightly over this

period, as reflected in the combined area of poor and became poor in the figure,

about one quarter of households moved into or out of poverty each year. Second, over

time, the number of households that were poor in the previous and were still poor in the

next period rose from 18 percent in 1987/88 to 31 percent in 1990/91. Over the much

longer period between 1990/91 and 2001/02, the percentage of chronic poor was only

slighter higher (35 percent) than in 1990/91. Third, poverty in the sample rose

substantially in 2001/02, though 15 percent of households made a transition out of

poverty in this 11 year period, essentially the same percentage as in the earlier period.

Poverty transitions using the 1987-91 average income and the 2001/02 incomes

are similar (Table 5). 33 percent of households were classified as poor in the first period

and 64 percent were poor in 2002. Only 9 percent of households rose out of poverty and

40 percent fell into poverty. Half of the sample had no change in poverty status. Poverty

actually fell among the households in the lowest two income quintiles of the first period

(from 83 to 73 percent), with 23 percent of these households ascending out of poverty.

Nearly one half of non-farm households in the sample descended into poverty in 2002,

compared with 38 percent of the farm households.

8

IV. Determinants of Household Welfare

Table 6 presents the results of several regressions on measures of welfare (natural

logarithms of real expenditures per adult equivalent and real incomes per adult

equivalent) using the panel data set. Village level dummy variables are also included to

control for unobserved fixed effects.

Regressions on the average real income per adult equivalent for the first period

(1986/87 to 1990/91) are similar to the results of McCullough and Baulch (2000) for the

entire sample (including the 103 households which could not be traced in 2001/02

(regression 1). Coefficients on household structure (number of male youths, number of

children, number of female youths), education (number of males with secondary

education), land (irrigated and non- irrigated) and capital (value of vehicles and tools) are

all significant at the 95 percent confidence level. Regressions on 2001/02 real incomes

per adult equivalent (not shown here) produced poor results, with few significant

variables, likely reflecting the high degree of variability in income from year to year.

Instead of real incomes per adult equivalent, we therefore use real expenditures as

a measure of household welfare that is generally more stable and a better reflection of

medium-term welfare than current income. Using average real expenditures per adult

equivalent as a dependent variable for 1990 and 1991 and period 1 averages for

explanatory variables produces results similar to regression 1, though the variables for

value of capital are no longer significant (regression 2). This regression performs well

for the 2001-02 data, as well (column 3). Education appears as a more important

explanatory variable in 2001/02, though, particularly education of the household head.

9

Regression 4 on real expenditure per capita uses a two-period panel of average

1989/90 1990/91 and 2001/02 controlling for random effects across households. The

coefficient of 0.487 on percentage of males with secondary education implies that adding

an additional educated male increases real expenditures by about (0.2)*(0.487) 1 = 10.2

percent; having a household head with primary education increases real expenditures by

exp(0.1949) 1 = 21.5 percent. Owning 5 acres of either irrigated or non- irrigated land

(a small farm by Pakistan standards) raises real expenditures by about 13 percent. The

regression coefficients also imply that village electrification raises real expenditures by

about 75 percent and paved roads approximately double real expenditures.

V. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The disaggregated analysis of household panel data for rural Pakistan presented in

this paper shows levels and trends of income vary substantially across region and over

time. Real incomes of many households declined between the early 1990s and 2002, in

spite of modest gains in agricultural output at the provincial and national levels. Net crop

income increased by 38 percent for the total sample and by 81 percent growth for poor

farmers, whose total incomes rose by 23 percent. Nevertheless, rural non-agricultural

incomes fell by 30 percent overall and by 16 percent for poor households. Thus, income

and employment multipliers of agricultural growth were insufficient to lead to substantial

gains in rural non-farm incomes. These findings emphasize the importance of raising

non-agricultural incomes through other pathways in rural Pakistan.

The analysis also highlights the crucial importance of location-specific factors in

driving rural incomes, not only because of agro-ecology, but also because of differences

in infrastructure and even social networks for migration. The decline in international

10

remittances was a major factor in driving overall income and poverty changes in three of

the four districts included in the sample.

Finally, this study shows the importance of education in raising real incomes in

Pakistan. Returns to education are positive and significant in all regressions. Moreover,

given the relatively low spillover effects of agricultural growth on rural non-farm

incomes, some combination of out- migration, increased worker remittances or rural non-

agricultural income growth separate from agricultural growth linkages, will be crucial for

reducing poverty in the future. Education is thus likely to become even more important

for raising households out of poverty in the future.

References

Adams, Richard and Jane He. 1996. Sources of Income Inequality and Poverty in Rural

Pakistan. Research Report 102. Washington, D.C., International Food Policy Research

Institute.

Alderman, Harold and Marito Garcia. 1993. Poverty, Household Security, and Nutrition

in Rural Pakistan. Research Report 96. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy

Research Institute.

Datt, Gaurav and Martin Ravallion. 1993. Regional Disparities, Targeting, and Poverty

in India, in M. Lipton and J. van der Gaag, Including the Poor. Washington, D.C.:

World Bank.

Dorosh, Paul A., Muhammad Khan Niazi and Hina Nazli. (2003). Distributional

Impacts of Agricultural Growth in Pakistan: A Multiplier Analysis. The Pakistan

Development Review. 42(3): 249-275.

Government of Pakistan (2003). Pakistan Economic Survey, 2002-03. Islamabad,

Pakistan: Finance Division, Economic Advisers Wing.

Malik, Sohail J. 2005. Agricultural Growth and Rural Poverty: A Review of the

Evidence. Pakistan Resident Mission Working Paper Series. Working Paper No. 2.

Islamabad: Asian Development Bank.

11

Malik, S. J. and Hina Nazli. 1998. Rural Poverty and Land Degradation: A Review of

the Current State of Knowledge, Pakistan Development Review 37(4).

McCullough, Neil and Bob Baluch. 2000. Simulating the Impact of Policy Upon

Chronic and Transitory Poverty in Rural Pakistan. Journal of Development Studies

36(6).

Sen, Binayak. 2003. Drivers of Escape and Descent: Changing Household Fortunes in

Rural Bangladesh. World Development 31(3):513-534.

World Bank. 2002. Pakistan Poverty Assessment; Poverty in Pakistan: Vulnerabilities,

Social Gaps, and Rural Dynamics. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

12

Table 1: Economic Structure of Sample Districts

District Attock Faisalabad Badin Lower Dir

(Province) (Punjab) (Punjab) (Sindh) (NWFP)

Area (thousand square kms) 6.86 5.86 6.73 1.58

Population 1998 (millions) 1.275 5.429 1.136 0.718

Population density (1998) 185.9 927.1 168.9 453.3

Urban population 0.271 3.11 0.186 0.044

Urbanization 21.3% 57.3% 16.4% 6.2%

Labor force in agriculture (%) 32.3 25.2 80.2 45.8

Land distribution (2000)

(percent of cropped area)

Less than 5 acres 17.4 31.2 9.3 71.3

5 25 acres 49.5 59.9 40.3 27.8

25 - 50 acres 17.6 6.5 18.0 0.4

50 acres or more 15.4 2.5 32.4 0.6

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Change in Cropped Area

1990 to 2000 16% 5% 40% -46%

Major crops (share of area, 2000)

Wheat 49% 37% 12% 74%

Cotton 0% 8% 1% 0%

Rice 1% 4% 36% 13%

Sugarcane 0% 12% 13% 0%

Others 50% 39% 38% 14%

Wheat yields (2002, tons/ha) 1.52 2.82 1.58 1.30

Source: 1980 and 1998 Population Censuses. 2000 Agricultural Census. Agricultural

Statistics of Pakistan.

13

Table 2: Physical Infrastructure of Sample Villages and Districts

District Attock Faisalabad Badin Lower Dir

(Province) (Punjab) (Punjab) (Sindh) (NWFP)

Panel Data Sample (number of villages)

Total villages

1988 8 5 19 12

2001 7 5 19 11

Villages electrified

1988 7 4 2 12

2001 7 5 10 11

Villages with paved roads

1988 1 0 4 6

2001 7 5 12 8

Villages with public drainage

1988 2 0 0 0

2001 1 1 0 1

District level Population Census data

Road density (kms/square km) 0.30 0.34 0.29 0.22

% Households with electricity

1980 n.a. 42 22 17

1998 67 61 35 49

% Households with piped water

1980 n.a. 12 4 7

1998 27 28 13 33

% Households without latrine

1980 n.a. 65 59 n.a.

1998 65 44 56 74

Source: 1988 and 2000 Pakis tan Population Censuses; IFPRI-PRHS Household Surveys

(various years).

14

Table 3: Real incomes in Rural Pakistan by Source and District, 1986/87-91/92 and 2002

District / Year

Rental

earnings

in crops

Net crop

profit

Farm

wage

income

Non-farm

income

Net

livestock

profit

Returns

to capital

Remit-

tances Pension

Total

income

All households by region

Faisalabad

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 1,139 4,708 186 5,232 2,269 1,276 1,709 56 16,480

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.069 0.286 0.011 0.317 0.138 0.077 0.104 0.003 1.000

% change to 2002 -10.4% 82.3% 101.0% 1.4% 9.7% -63.9% -92.8% 28.2% 11.7%

Attock

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 816 1,622 50 5,206 1,343 988 1,576 399 11,996

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.068 0.135 0.004 0.434 0.112 0.082 0.131 0.033 1.000

% change to 2002 -61.4% 106.5% 221.8% -8.1% 75.3% -71.4% 7.8% -47.7% 9.2%

Badin

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 2,024 4,340 297 3,589 2,197 331 556 72 13,264

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.153 0.327 0.022 0.271 0.166 0.025 0.042 0.005 1.000

% change to 2002 -29.5% 39.7% 5.7% -58.8% -32.7% -19.2% -82.6% 2.5% -15.7%

Dir

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 683 1,714 13 5,230 1,862 116 4,028 42 13,683

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.050 0.125 0.001 0.382 0.136 0.008 0.294 0.003 1.000

% change to 2002 -17.6% -47.7% -61.8% -67.3% -92.8% 44.0% -53.5% 104.2% -60.5%

Source: Authors calculations from IFPRI panel data set and PRHS (2001/02).

15

Table 4: Real incomes in Rural Pakistan by Source for Poor Households, 1986/87-91/92 and 2002

District / Year

Rental

earnings

in crops

Net crop

profit

Farm

wage

income

Non-farm

income

Net

livestock

profit

Returns

to capital

Remit-

tances Pension

Total

income

Full sample

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 1,156 3,436 157 4,472 1,882 575 1,780 123 13,522

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.086 0.254 0.012 0.331 0.139 0.043 0.132 0.009 1.000

% change to 2002 -24.4% 37.8% 37.2% -30.2% -18.1% -49.7% -49.4% -15.7% -13.1%

Poor households in 1986/87-91/92 (bottom 40 percent)

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 215 1,705 167 2,911 1,476 75 648 61 7,239

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.030 0.236 0.023 0.402 0.204 0.010 0.090 0.008 1.000

% change to 2002 -10.2% 80.7% 76.3% -15.7% -6.9% 60.0% 2.5% 22.0% 13.9%

Poor farm households

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 245 2,313 177 2,300 1,733 100 593 61 7,498

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.033 0.308 0.024 0.307 0.231 0.013 0.079 0.008 1.000

% change to 2002 -5.2% 80.7% 54.0% -16.6% 3.0% 63.2% 6.3% 1.8% 23.1%

Poor non-farm households

1986/87-91/92 (Rs/hh) 135 103 140 4,521 797 9 793 61 6,556

1986/87-91/92 (share) 0.021 0.016 0.021 0.690 0.122 0.001 0.121 0.009 1.000

% change to 2002 -33.9% 81.4% 150.8% -14.4% -63.4% -30.0% -5.0% 74.7% -14.0%

Source: Authors calculations from IFPRI panel data set and PRHS (2001/02).

16

Table 5: Poverty Transitions in Rural Pakistan: 1987-91 to 2002

1987-1991 2002 Chronic Chronic Sample

Total Poor Total Poor Poor Ascending Non-Poor Descending Size

Entire Sample 33% 64% 24% 9% 26% 40% 571

Bottom 40% 83% 73% 60% 23% 4% 13% 229

Farm 32% 60% 22% 10% 30% 38% 431

Non-Farm 37% 79% 31% 6% 15% 48% 140

Notes:

The bottom 40 percent is defined according to the 5-year average of real income per adult

equivalent from 1987 to 1991.

Farmer households have a minimum average of 0.5 acres of land in operation (on average?) over

the 1987 to 1991 period.

Poverty is defined relative to the national poverty line of 3,648 (1991) Rs/adult equivalent/year.

Figure 1: Rural Poverty Transitions in Pakistan, 1987/88 to 2001/02

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1987/88 1988/89 1989/90 1990/91 2001/02

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

o

f

H

o

u

s

e

h

o

l

d

s

Poor Became Poor Became Non-Poor Non-Poor

Source: Authors calculations from IFPRI panel data set and PRHS (2001/02).

17

Table 6: Determinants of Real Incomes and Expenditures in Rural Pakistan, Regression Results

Period Average 87-91 Average 90-91 2002 Panel changes

Dependent variable Real income Real Expenditure Real Expenditure Real Expenditure

Coef. t-statistic Coef. t-statistic Coef. t-statistic Coef. z-statistic

Share of remittances in income --- --- -0.0459 -0.30 0.0020 0.07 0.0055 0.13

Male youths (% of household) -0.9445 ** -5.20 -0.7631 ** -2.69 -0.1289 -0.49 -0.4667 * -1.89

Children (% of household) -0.6292 ** -4.89 -0.6510 ** -3.30 -0.4005 * -1.75 -0.4698 ** -2.92

Female youths (% of household) -0.8836 ** -4.96 -0.6765 ** -2.78 -0.5691 ** -2.17 -0.5499 ** -2.32

Males w/ basic educ. (% of males) 0.1145 0.73 -0.1592 -0.76 -0.1146 -0.97 -0.1844 -0.90

Males w/ second. educ. (% of males) 0.9198 ** 5.06 0.6295 ** 2.73 0.3489 ** 2.15 0.4869 ** 2.14

Females w/ basic educ. (% of females) 0.0316 0.16 0.0663 0.25 -0.0677 -0.36 -0.1544 -0.62

Females w/ sec. educ. (% of females) 0.1913 0.38 -0.6054 -0.94 0.2846 0.96 0.4752 0.74

Household head basic educ. (yes = 1) 0.0788 1.44 0.0126 0.18 0.1854 ** 2.78 0.1949 ** 3.01

Rainfed land owned (acres) 0.0066 ** 3.07 0.0078 ** 3.84 0.0088 ** 3.24 0.0099 ** 4.45

Irrigated land owned (acres) 0.0163 ** 7.04 0.0115 ** 2.67 0.0049 ** 2.61 0.0096 ** 5.15

Value of vehicles (th 2002 Rs) 0.0016 ** 2.23 0.0004 0.54 0.0000 0.92 0.0008 ** 2.23

Value of tools (th 2002 Rs) 0.0028 ** 3.13 0.0002 0.15 0.0000 0.05 0.0018 ** 2.56

Own a tractor (yes = 1) 0.0960 ** 2.04 0.0023 0.03 0.0099 0.09 -0.5273 ** -8.78

Village electrified 0.1101 0.39 -0.0575 -0.15 0.7528 1.41 0.5659 ** 8.89

Village - paved road 0.4614 1.38 -0.6392 -1.47 0.3503 * 1.68 0.6975 ** 14.55

Village - public drainage -0.4702 ** -1.92 -0.0817 -0.43 -0.5613 -0.99 -0.0103 -0.12

Constant 9.2359 ** 24.37 8.7335 ** 11.03 8.5548 ** 108.06 7.6577 ** 87.01

N 571 571 571 1142

R-squared 0.545 0.259 0.259 0.339

within --- --- --- 0.4745

between --- --- --- 0.175

* Significant at 90 percent confidence level; ** Significant at 95 percent confidence level.

Note: Regression 4: Random effects estimation: u_i ~ Gaussian, Wald chi2(17) = 576.36. corr(u_i, X)=0 (assumed), Prob > chi2 = 0.000.

Source: Authors calculations.

You might also like

- Choice of Techniques: The Case of Cottonseed Oil-Extraction in PakistanDocument10 pagesChoice of Techniques: The Case of Cottonseed Oil-Extraction in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Production Functions For Wheat Farmers in Selected Districts in Pakistan: An Application of A Stochastic Frontier Production Function With Time-Varying Inefficiency EffectsDocument36 pagesProduction Functions For Wheat Farmers in Selected Districts in Pakistan: An Application of A Stochastic Frontier Production Function With Time-Varying Inefficiency EffectsInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- List of PublicationsDocument1 pageList of PublicationsInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- A Note On The Edible Oil Milling Sector, Output, Value-Added and EmploymentDocument15 pagesA Note On The Edible Oil Milling Sector, Output, Value-Added and EmploymentInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Female Time Allocation in Selected Districts of Rural PakistanDocument13 pagesDeterminants of Female Time Allocation in Selected Districts of Rural PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- The Role of Institutional Credit in The Agricultural Development of PakistanDocument10 pagesThe Role of Institutional Credit in The Agricultural Development of PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Rural-Urban Differences and The Stability of Consumption Behavior: An Inter-Temporal Analysis of The Household Income Expenditure Survey Data For The Period of 1963-85Document12 pagesRural-Urban Differences and The Stability of Consumption Behavior: An Inter-Temporal Analysis of The Household Income Expenditure Survey Data For The Period of 1963-85Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES Production Functions Using Aggregative Data On Selected Manufacturing Industries in PakistanDocument28 pagesEstimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES Production Functions Using Aggregative Data On Selected Manufacturing Industries in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES and VES Production Functions Using Firm-Level Data For Food-Processing Industries in PakistanDocument24 pagesEstimation of Elasticities of Substitution For CES and VES Production Functions Using Firm-Level Data For Food-Processing Industries in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Rural Poverty in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument20 pagesRural Poverty in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Differential Access and The Rural Credit Market in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument8 pagesDifferential Access and The Rural Credit Market in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Solving Organizational Problems With Intranet TechnologyDocument16 pagesSolving Organizational Problems With Intranet TechnologyInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Consumption Pattern of Major Food Items in Pakistan: Provincial Sectoral, and Inter-Temporal Differences, 1979-85"Document6 pagesConsumption Pattern of Major Food Items in Pakistan: Provincial Sectoral, and Inter-Temporal Differences, 1979-85"Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Production Relations in The Large Scale Textile Manufacturing Sector of PakistanDocument16 pagesAn Analysis of Production Relations in The Large Scale Textile Manufacturing Sector of PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Capital Labour Substitution in The Large-Scale Food-Processing Industry in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceDocument12 pagesCapital Labour Substitution in The Large-Scale Food-Processing Industry in Pakistan: Some Recent EvidenceInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Some Tests For Differences in Consumption Patterns: The Impact of Remittances Using Household Income and Expenditure Survey 1987-1988Document13 pagesSome Tests For Differences in Consumption Patterns: The Impact of Remittances Using Household Income and Expenditure Survey 1987-1988Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Development Strategy - The Importance of The Rural Non Farm Economy in Growth and Poverty Reduction in PakistanDocument16 pagesRethinking Development Strategy - The Importance of The Rural Non Farm Economy in Growth and Poverty Reduction in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Rural Poverty and Land Degradation: A Review of The Current State of KnowledgeDocument18 pagesRural Poverty and Land Degradation: A Review of The Current State of KnowledgeInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Poverty DimentioDocument14 pagesPoverty DimentioNaeem RaoNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitating Agriculture and Promoting Food Security Following The 2010 Pakistan Floods: Insights From The South Asian Experience.Document26 pagesRehabilitating Agriculture and Promoting Food Security Following The 2010 Pakistan Floods: Insights From The South Asian Experience.Innovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Role of Infaq in Poverty Alleviation in PakistanDocument18 pagesRole of Infaq in Poverty Alleviation in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Rural Poverty and Credit Used: Evidence From PakistanDocument18 pagesRural Poverty and Credit Used: Evidence From PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its Impact On Poverty in PakistanDocument47 pagesGlobalization and Its Impact On Poverty in PakistanInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- PunjabEconomicReport2007 08Document225 pagesPunjabEconomicReport2007 08Ahmad Mahmood Chaudhary100% (2)

- National Plan of Action For ChildrenDocument163 pagesNational Plan of Action For ChildrenInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Rural Investment Climate Survey: Background and Sample Frame DesignDocument29 pagesPakistan Rural Investment Climate Survey: Background and Sample Frame DesignInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Access To Finance in NWFPDocument97 pagesAccess To Finance in NWFPInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Poverty Marker and Loan Classification Systems in Multilateral Development Banks With Lessons For The Asian Development BankDocument28 pagesAn Assessment of The Poverty Marker and Loan Classification Systems in Multilateral Development Banks With Lessons For The Asian Development BankInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Tax Potential in NWFPDocument79 pagesTax Potential in NWFPInnovative Development Strategies (Pvt.) LtdNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Strategies in The Job-Search ProcessDocument27 pagesStrategies in The Job-Search ProcessKhan AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Own Your Computer Policy PDFDocument2 pagesOwn Your Computer Policy PDFvimmydivyaNo ratings yet

- Basic Consideration in MasDocument8 pagesBasic Consideration in Masrelatojr25No ratings yet

- Ra 10771Document8 pagesRa 10771Jayvie GacutanNo ratings yet

- Internship ReportDocument51 pagesInternship ReportMd. Saber Siddique100% (1)

- Facts:: Francisco V. Del Rosario, Petitioner, Vs - National Labor Relations Commission - Writ of Execution Expired LicenseDocument2 pagesFacts:: Francisco V. Del Rosario, Petitioner, Vs - National Labor Relations Commission - Writ of Execution Expired LicenseMichelle Joy ItableNo ratings yet

- Salary Statement 10 01 2018Document7 pagesSalary Statement 10 01 2018lewin neritNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Employee Engagement and Satisfaction With Reference To Case of Asian PaintsDocument2 pagesAssignment: Employee Engagement and Satisfaction With Reference To Case of Asian PaintsRameez AhmedNo ratings yet

- Npos vs. PoDocument4 pagesNpos vs. Pocindycanlas_07No ratings yet

- Calculation of Benefit Value On Pension Fund Using Projected Unit CreditDocument6 pagesCalculation of Benefit Value On Pension Fund Using Projected Unit CreditAprijon AnasNo ratings yet

- Reeves - Twentieth-Century America - A Brief History (1999) PDFDocument322 pagesReeves - Twentieth-Century America - A Brief History (1999) PDFEn T100% (1)

- 6th Pay Commission GR For MaharashtraDocument2 pages6th Pay Commission GR For Maharashtratushar_ingale100% (1)

- Great Pacific Life Employees vs. Great Pacific Life AssuranceDocument15 pagesGreat Pacific Life Employees vs. Great Pacific Life AssuranceHipolitoNo ratings yet

- ACCT 701 Chapter 10 AtkinsonDocument54 pagesACCT 701 Chapter 10 AtkinsonAnonymous I03Wesk92No ratings yet

- PSM Compliance ManualDocument6 pagesPSM Compliance ManualMohammed Zubair100% (1)

- Social Concerns and Social IssuesDocument26 pagesSocial Concerns and Social IssuesVoxDeiVoxNo ratings yet

- Virgel Dave Japos VsDocument13 pagesVirgel Dave Japos VsPat PoticNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument17 pagesAnnotated BibliographypingoroxzNo ratings yet

- Home Based Contact Centres - A Time For New ThinkingDocument12 pagesHome Based Contact Centres - A Time For New ThinkingMauriceWhelanNo ratings yet

- Toeic Basic - Textbook - Tuyen Tuyen ToeicDocument311 pagesToeic Basic - Textbook - Tuyen Tuyen ToeicVương Thảo LinhNo ratings yet

- WB Police Recruitment 2018Document7 pagesWB Police Recruitment 2018TopRankersNo ratings yet

- Cachitty@samford - Edu: Chad Chitty Cell: (205) 317-2072 Current AddressDocument2 pagesCachitty@samford - Edu: Chad Chitty Cell: (205) 317-2072 Current Addressapi-240184674No ratings yet

- VP Director Compensation Benefits in New York City Resume Alexander DeGrayDocument4 pagesVP Director Compensation Benefits in New York City Resume Alexander DeGrayAlexanderDeGrayNo ratings yet

- NikeDocument11 pagesNikeAnimo TonibeNo ratings yet

- Central Information Commission: Prof. M. Sridhar Acharyulu (Madabhushi Sridhar)Document11 pagesCentral Information Commission: Prof. M. Sridhar Acharyulu (Madabhushi Sridhar)Parivar ManchNo ratings yet

- SBN-0832: Philippine Nursing Practice Reform ActDocument28 pagesSBN-0832: Philippine Nursing Practice Reform ActRalph RectoNo ratings yet

- Abraham Maslow Theory NewDocument19 pagesAbraham Maslow Theory NewRidawati LimpuNo ratings yet

- Operations Management Chapter 1 and 2Document8 pagesOperations Management Chapter 1 and 2NOOBONNo ratings yet

- Sagicor Insurance Company V Carter Et Al AXeZm3Cdo5CdlDocument23 pagesSagicor Insurance Company V Carter Et Al AXeZm3Cdo5CdlNathaniel PinnockNo ratings yet

- Surigao Del Sur State University College of Business ManagementDocument5 pagesSurigao Del Sur State University College of Business ManagementKuya KimNo ratings yet