Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fundamental Hebrew Grammar

Uploaded by

joabeilonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fundamental Hebrew Grammar

Uploaded by

joabeilonCopyright:

Available Formats

Fundamental

Biblical Hebrew

and

Fundamental

Biblical Aramaic

ALSO FROM CONCORDIA

Hebrew and Greek Studies

Workbook and Supplementary Exercises

for Fundamental Biblical Hebrew

and Aramaic

Andrew H. Bartelt and Andrew E.

Steinmann

Intermediate Biblical Hebrew:

A Reference Grammar with Charts

and Exercises

Andrew E. Steinmann

Concordia Hebrew Reader: Ruth

John R. Wilch

Fundamental Greek Grammar

James W. Voelz

Religion and Resistance in Early Judaism:

Greek Readings in 1 Maccabees

and Josephus

John G. Nordling

Biblical Studies

Concordia Commentary Series:

A Theological Exposition

of Sacred Scripture

Leviticus, John W. Kleinig

Joshua, Adolph L. Harstad

Ruth, John R. Wilch

Ezra and Nehemiah, Andrew E.

Steinmann

Proverbs, Andrew E. Steinmann

Ecclesiastes, James Bollhagen

The Song of Songs, Christopher W.

Mitchell

Isaiah 4055, R. Reed Lessing

Ezekiel 120, Horace D. Hummel

Ezekiel 2148, Horace D. Hummel

Daniel, Andrew E. Steinmann

Amos, R. Reed Lessing

Jonah, R. Reed Lessing

Matthew 1:111:1, Jeffrey A. Gibbs

Matthew 11:220:34, Jeffrey A. Gibbs

Luke 1:19:50, Arthur A. Just Jr.

Luke 9:5124:53, Arthur A. Just Jr.

Romans 18, Michael Middendorf

(forthcoming May 2013)

1 Corinthians, Gregory J. Lockwood

Colossians, Paul E. Deterding

Philemon, John G. Nordling

2 Peter and Jude, Curtis P. Giese

13 John, Bruce G. Schuchard

Revelation, Louis A. Brighton

FUNDAMENTAL

BIBLICAL HEBREW

ANDREW H. BARTELT

FUNDAMENTAL

BIBLICAL ARAMAIC

ANDREW E. STEINMANN

Fundamental Biblical Hebrew 2000 Concordia Publishing House

Fundamental Biblical Aramaic 2004 Andrew E. Steinmann

Published by Concordia Publishing House

3558 S. Jeferson Ave.,

St. Louis, MO 63118-3968

1-800-325-3040 www.cph.org

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Concordia

Publishing House.

Tis work uses the SBL Hebrew Unicode font developed by the Font Foundation

under the leadership of the Society of Biblical Literature. For further

information on this font or on becoming a Font Foundation member, see

http://www.sbl-site.org/educational/biblicalfonts.aspx

Te TranslitLSU font used to print this book is available from Linguists Sofware, Inc.,

PO Box 580, Edmonds, WA 98020-0580, USA; telephone (425) 775-1130;

www.linguistsofware.com.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12

FUNDAMENTAL

BIBLICAL HEBREW

ANDREW H. BARTELT

Contents

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xiii

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1. Spelling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

2. Noun Morphology: Gender and Number . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3. Prefixes: Article, Prepositions, the Conjunction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

4. Verb Morphology: The Perfect Aspect

(Afformative Verb Forms). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

5. Verb Morphology: Variations of the Perfect Aspect . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

6. Verb Morphology: The Imperfect Aspect

(Preformative Verb Forms) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

7. Verb Morphology: Major Variations of the Imperfect Aspect . . . . . 54

8. Waw Consecutive (wayyiql) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

9. Noun Morphology: Absolute and Construct States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

10. Personal Pronouns, Pronominal Suffixes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

11. Adjectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

12. Participles, Relative Clauses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

13. Nominal Sentences of Existence; Possession; Interrogatives . . . . . . . 118

14. Imperative, Jussive, Cohortative . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

15. Infinitives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

16. Object Suffixes, Review of Qal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

17. Derived Conjugations, Piel Conjugation (D) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

18. Hiphil Conjugation (H) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

19. Niphal Conjugation (N) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

20. Pual (Dp) and Hithpael (HtD) Conjugations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193

21. Hophal Conjugation (Hp), Hishtaphel, Qal Passive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

22. Geminate Verbs; Polel, Polal, Hithpolel; and Verbal Hendiadys . . . 210

23. Numerals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

24. Masoretic Accents and Spelling, Sentence Syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

Appendices

I. Noun Formation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

II. Pronominal Suffixes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

III. Regular (Strong) Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

IV. Irregular Verbs

A. I-Guttural Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

B. II-Guttural Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 244

C. III-Guttural Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246

D. III-Alep Verbs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 248

E. I-Nun Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 250

F. I-Yo (Original I-Waw) Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

G. Hollow (II-Waw / Yo) Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

H. III-H Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 256

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 258

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

ix

Preface

T

he title of this textbook addresses at least two basic issues of scope

and purpose. Te term Biblical Hebrew indicates a focus on a specifc

corpus of Hebrew texts also known as the Hebrew Scriptures, the Tanak, or

the so-called Old or First Testament. Even within that limited corpus, however,

the reader fnds a wide spectrum of stylistic, historical, and even dialectical difer-

ences and distinctions, some of which still remain discussed and debated within

learned circles. Variations in spelling, oddities in morphology, archaic forms as

well as characteristics of later development, or the vast stylistic and even gram-

matical diferences between prose and poetry soon confront the beginning reader

of the biblical text. Nevertheless, there is signifcant consensus concerning basic

Hebrew grammar of the so-called classical, monarchic, or pre-exilic period of

biblical Hebrew, and it is essentially such a consensus that is refected in the pre-

sentation in this textbook.

With that focus, this is also a fundamental approach. Te objective of this text-

book is to provide a basic understanding of grammar, including vocabulary, mor-

phology, and syntax, to facilitate reading of elementary to intermediate level bibli-

cal texts with the aid of a lexicon. While the presentation is consistent with the

insights of more technical grammars, many fne points are lef for the additional

refnement that comes with further study.

Alreadyespeciallyat a fundamental level, however, students should

be aware of two axioms of language study: all grammars leak (as one pundit

has put it), and all language teachers lie (especially at the fundamental level), or

at least they occasionally conceal the fact that all grammars leak! Tat is to say that

a fundamental approach focuses on the regular and normative with the full rec-

ognition that the realities of languages are flled with irregularities and deviations

from the norm, some of which can be explained and predicted, some of which

cannot. At the same time, such irregularities confrm both the existence and

the helpfulness of recognizing and learning the regular principles and patterns.

Exceptions prove the rules even as they probe the rules.

Tis textbook unashamedly follows a more traditional and deductive approach,

emphasizing the memorization of basic vocabulary, morphology, and paradigms.

While an artifcial and unnatural mode of learning a language, this method is both

time-tested and time-efcient in presenting and learning material in a systematic

manner and logical sequence.

On the other hand, there is an intentionally more inductive and user-

friendly manner to the presentation. Students will be engaged in the actual

x Fundamental Biblical Hebrew

biblical text already in chapter one. Examples and exercises move logically from

the known to the unknown, from regular to irregular forms, from general rules

to exceptions. Technical fne points are acknowledged but not overly emphasized.

An outline format provides a sense of order and is reproduced in summary form at

the end of each chapter to faciliate self-study and review.

Both students and instructors might note the following specifc features which

may add to the usefulness of this text:

1. Te chapters tend to treat a specifc grammatical topic in a com-

plete manner. For example, the defnite article is covered in one chapter,

presented in logical order from the regular to the irregular features.

Pronouns are discussed in a holistic way (Chapter 10), so that the stu-

dents quickly see the relationships between the independent pronouns

and the various uses of pronominal sufxes. Experience has shown this

form of organization to be extremely helpful also for later review and

reference.

2. Tus some chapters are longer than others and should not be per-

ceived as lessons in every case. Instructors can easily adjust to the

needs of a class, including multiple presentations on single chapters

as needed. Certain exercises and drills are prescribed at specifc points

within chapters.

3. Te presentation of verb forms begins with the fnite tenses (and not the

participle) to enable understanding of common sentence structure early

on. Beginning with the traditional paradigms of Qal (G) perfect and

imperfect (using the standard third-second-frst person format), the

student is immediately introduced to the so-called waw consecutive

(wayyiql) to facilitate reading narrative texts within a few lessons.

4. Since the vast majority of verb forms are in the Qal conjugation (68.8

percent, according to Waltke and OConnor, p. 361), this binyan is pre-

sented fully (moving from regular to irregular forms in logical and reg-

ularized sequence) as a template for understanding the distinctions in

form and translation of the other conjugations. While traditional termi-

nology is used (Qal, Piel, Hiphil, etc.), the student is also introduced to

the general Semitic descriptors (G, D, H, etc.).

5. Te vocabulary has been carefully selected on the basis of frequency and

biblical use. At the conclusion of the book, the student should be famil-

iar with most words in the 100+ frequency categories. Te number of

new words in each chapter is slightly smaller than in some textbooks

to reduce the burden of rote memorization of vocabulary, arguably the

most difcult aspect of learning Hebrew, especially for adult learners.

Words introduced in a chapter are ofen used in examples within the

presentation of that chapter, and no additional words are used in exam-

ples or in presentation that have not already been learned. Grouping of

Preface xi

vocabulary by idiomatic phrases, word pairs, or semantic felds has been

attempted where possible.

6. Te exercises, like the presentations in each chapter, are structured

to move from the regular to the irregular, from the known to the

unknown. Te drills are constructed with very specifc teaching objec-

tives in mind for every question, and they move logically to illustrate

specifc features. Teachers will quickly observe that drills can be used

as supplemental and inductive teaching tools, and that ofen a students

question will be answered by the next example. Tis also helps the

student in self-study and review.

7. Sentences used both as examples and as translational exercises are care-

fully written to teach biblical style and idiom while meeting the spe-

cifc learning objectives of each chapter. Tis has proven to be more

helpful than fnding actual biblical quotations, which, while psychologi-

cally helpful in presenting real biblical texts, do not always achieve the

most efective pedagogical results.

8. A supplemental exercise book with additional and annotated bibli-

cal readings provides a workbook for completing all the exercises (in

larger format), allowing the exercises in the textbook to remain clean

for students to use as review, if desired. Te workbook will also contain

an answer key, a composite list of each chapter summary, and a

larger version of the noun and verb paradigm charts from the appendi-

ces in the textbook.

xiii

Acknowledgments

T

his work is dedicated to all students of the Hebrew Scriptures, past,

present, and future, as they share the joy of being engaged by the bibli-

cal text through its original language. As those who introduced me to

the fundamentals of biblical Hebrew and who taught with such a wonderful

and contagious enthusiasm for both language and text, I am grateful to Roddy

Braun, Herbert Spomer, Merlin Rehm, and John Ribar, participants at that time

in the great educational enterprise known as Concordia Senior College. Tose

who honed those basic skills into scholarly tools include Ronald Clements and

especially Henry St. John Hart, whose love for both the language and his learn-

ers remains legendary in the lore of Cambridge. Recognition is due those at the

University of Michigan who placed Hebrew into the larger world of the Ancient

Near East: George Mendenhall, Charles Krahmalkov, Piotr Michalowski, Peter

Machinist, and especially David Noel Freedman, whose dedication to a close and

careful reading of texts highlights the importance of appreciating both basic struc-

tures and sophisticated nuances of grammar and style.

Above all, I would honor my teachers, colleagues, and friends at

Concordia Seminary, who share also the profound message of Gods salvation

in yea hamma, which is the truth that the text conveys. Among so many

I would note especially Horace Hummel, Paul Raabe, Paul Schrieber, and James

Voelz, whose encouragement has taken the form of both personal motivation

and professional model through his well received and much used Fundamental

Greek Grammar, to which this work stands as both complement and compliment.

Of those directly involved in this project I would hold in highest esteem

the hundreds of students from whom I have learned much in the teaching of

biblical Hebrew, especially those who have served in the living laboratory

as these materials were produced and tested. For some, those pages are prob-

ably long lost from a loose-leaf binder; for many, I hope, this book will serve

as a more permanent replacement. Especially helpful, also in feld testing these

materials and ofering numerous suggestions, are colleagues Stephen Stohlmann

of Concordia University, St. Paul, and Mark Meehl of Concordia University,

Seward.

Closer to home, William Carr has made signifcant contributions toward both

presentation and pedagogy, as has Philip Penhallegon, who has also come to know

with patience and good cheer the very close reading of text that is the editorial

process. Tis project would not have been completed without his valuable assis-

tance, and I owe him a special debt of gratitude and my highest respect for his

xiv Fundamental Biblical Hebrew

careful and diligent work. I would also extend to Marilyn Kincaid a hearty th

rabbh for her encouragement and energetic ima trh from the perspective of

the synagogue.

Finally, I would express my appreciation for the support and patience of those

involved with Concordia Academic Press, to Charles Arand and Ken Wagener,

and especially to Wilbert Rosin, whose steady guidance has played a major role in

bringing this project to publication.

Above all others, it is to my family, to Lucy, Marybeth, Allison, and Amy, whose

patience and prayer, love and loyalty, support and sacrifce are treasured beyond

measure, that I ofer my loving thanks even as I repent of the time too ofen taken

from them.

May God grant wisdom and insight to all whose study of biblical Hebrew will

provide greater understanding of Gods torah and truth, of His goodness and grace,

of His prophetic Word and of that prophetic Word made sure in the Word Made

Flesh.

1

Introduction

L

earning biblical Hebrew is, indeed, fundamental for anyone who takes seri-

ously the text of the Hebrew Scriptures. Every student of literature knows the

basic importance of utilizing the primary sources and original texts,

but those who understand such scripture as an authoritative Word of God have

a particular interest in the particularities of that text. Luthers comments regard-

ing the need for knowing and using the biblical languages in pastoral ministry

are well known but worth repeating:

Let us, then, foster the languages as zealously as we love the Gospel. . . . Let

us ever bear this in mind: we shall have a hard time preserving the Gospel

without the languages. The languages are the sheath in which this sword of

the Spirit is contained. They are the case in which we carry this jewel. . . .

Although faith and the Gospel may be preached by ordinary ministers

without the languages, still such preaching is sluggish and weak, and the

people finally become weary and fall away. But a knowledge of the language

renders it lively and strong, and faith finds itself constantly renewed through

rich and varied instruction.

1

Te Hebrew language itself has a long and noble history, though modern lin-

guistic research has dispelled the romantic notion fostered at least since Jerome

that God communicated a hebraica veritas through a special language of revela-

tion. Quite the opposite is true, with even greater theological signifcance. Not

unlike koine Greek, biblical Hebrew was a common and popular language, very

much integrated into the everyday realities of life and woven into the fabric of a

particular social-cultural history that, in turn, was set within the larger context of

the ancient world.

As a Semitic language, biblical Hebrew is part of a vast family of ancient Near

Eastern languages that is ofen divided into East Semitic or Akkadian (Babylonian

and Assyrian) in the Mesopotamian areas and into West Semitic that includes

the languages of Canaan. Further dividing into quadrants, the Mesopotamian lan-

guages make up a northeastern group, with various forms of Arabic to the south-

east and southwest. From the northwest quadrant of this entire region comes the

family of Northwest Semitic that divides into Ugaritic, Aramaic, and Canaanite.

Te Canaanite subgroup includes Hebrew, along with Phoenician, Moabite,

Ammonite, Edomite, and some lesser-known dialects.

Within the Bible itself, the few references to Hebrew describe persons or

a social group. Te language of Jerusalem and Judah is once called only the tongue

1 Martin Luther, To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany That They Establish

and Maintain Christian Schools in Luthers Works, American Edition, vol. 45,

ed.Walther I. Brant (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg, 1962), 359ff. passim.

2 Fundamental Biblical Hebrew

(lip) of Canaan (Isaiah 19:18) or otherwise simply Judahite (as distinct from

Aramaic, 2 Kings 18:26, 28 = Isaiah 36:11, 13). Students should consult standard

reference works for further detail concerning the history and place of the Hebrew

language, including inscriptional evidence and the ancient poetry which refects

the oldest form of the language within the biblical corpus.

Te importance of learning Hebrew for biblical studies cannot be over-

stated. Both Judaism and Christianity share a common bond in claiming the

Hebrew Scriptures as their own. Even for Christians, these texts (including the

chapters in Ezra and Daniel written in Aramaic) comprise about 75 percent of

the Bible, and knowledge of this First Testament is simply fundamental to

understanding the Jewish religious claims of the frst century that came to be

called Christianity (from the Greek word for messiah) and for understand-

ing the Jewish writings that became the New Testament. Indeed, anyone who

would understand the Scriptures as authoritative certainly must recognize

that they were not written in English. Such students will rejoice at the insight

gained in reading the biblical text in the very language and words of Moses and

the prophets.

In addition to the obvious awareness that any translation only approximates the

original, students will also quickly realize that diferences in various translations,

from questions of vocabulary or nuance to variants in the ancient manuscripts,

can only be addressed through access to the original sources. So also word studies,

concordance work, and other textual research cannot yield any signifcant results

without reference to the actual biblical text in its original language and without an

understanding of basic principles and practices of translation. To be sure, numer-

ous scholarly tools, reference works, biblical helps, and a host of modern transla-

tions can aid the Bible reader, but those who would be true students and interpret-

ers of the text are soon aware of the limitations of a translation-bound approach.

Although so ofen taken for granted, clear communication through careful

use of language is ofen more difcult than it may appear, and students of even

ancient languages may well discover a new appreciation and understanding for

their own mother tongue, as well as for the art of translation and of the transfer-

ence of message and meaning from source to receptor, both within and across

linguistic, cultural, and chronological barriers. Indeed, it is ofen at the level of

simple translation that much of the interpretive work is appreciated and already

achieved.

Finally, the study of biblical language draws us into the realities and the partic-

ularities of the biblical world, even into the very lives of those to whom God chose

to reveal His plan of salvation, for them and for all. Indeed, the fact that God chose

an ancient language of real people in a particular time and place is signifcant in

itself, but it is also consistent with His mode of revelation and communication

throughout history. Difcult though it may seem to bridge the gap from ancient

language to modern reader, God used, and still uses, ordinary words to speak the

most extraordinary message, the common to communicate the most uncommon,

even as He chose to send His divine Word in human body and blood.

3

1

Spelling

1 The Hebrew Alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet consists of 22 consonantal signs (read from right

to left). (See table below, D, p. 4).

/

A. Six letters have both a hard (stop) and a soft (spirant) sound:

= bgdkpt, known as the b

e

g

a

d k

e

p

a

t letters

A dot (dagesh lene) marks the hard sound

(used following a consonant or no sound).

The absence of the dagesh lene marks the soft sound

(following a vowel).

B. Five letters have a final form, used at the end of a word:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

C. Four letters are distinguished as guttural letters (sound is made

in the back of the throat, from the Latin guttur), which cause some

special problems in spelling and pronunciation:

( )

NOTE: Re shows one of the problems of the guttural letters, to be

discussed below ( 3 F, p. 10).

4 Hebrew Chapter 1

D. Summary of Consonantal Alphabet

sign name transliteration sound

dagesh

lene

final

form guttural

alep (glottal stop)

be van

b bed

gimel g dog

g get

dale these

d dog

h h hay

waw w

way

(also v, vav)

zayin z zebra

e Bach

e get

yo y yet

kap ache ( )

k key

lame l lad

mem m mad

nun n now

samek s sip

ayin (guttural stop)

peh p phone

p pot

ade pots

qop q unique

re r rat ( )

in sad

in shine

taw thin

t top

Spelling 5

COMPLETE DRILL 1A

2 Vowels (See vowel chart below, D, p. 6)

A. Vowels are divided into three families:

a / (e) i / (o) u

B. Within each family there are long and short vowels. Long vowels

can shorten; short vowels can lengthen.

1. a family:

short: paa ( )

long: qme ( )

2. (e) / i family:

short: segl ( )

req ( )

long: r ( )

3. (o) / u family:

short: qme-p ( )

qibb ( )

long: lem ( )

NOTE: The name of each vowel is a Hebrew word represented

in transliteration. Hereafter, the vocalic diacritical marks will

be omitted for simplicity.

C. Some long vowels are marked by vowel letters called mater letters

(from matres lectionis, Latin for mothers [helpers] of reading).

Such letters do not function as consonants but simply indicate a

long vowel.

used with a family vowels

used with e / i family vowels (and sometimes a)

used with o / u family vowels

NOTE: Vowels marked with mater letters are unchangeable. They

will not ordinarily shorten.

6 Hebrew Chapter 1

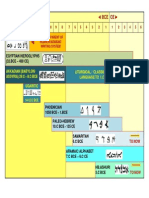

D. Vowel chart

vocal shewa

short

vowels

long

vowels

with

mater

letter

vowel

family regular

composite

(with

gutturals)

( e )

aep-

paa

( )

paa

(a)

father

(dad)

qame

( )

father

(h)

father

A

aep-

segol

( )

segol

( e )

bet

ere

( )

they

( )

( )

they

(E) / I

ireq

( i )

bit

( )

unique

aep-

qame

( )

qame

aup

( o )

bottle

olem

( )

bone

( )

bone

(O) / U

qibbu

( u )

but

ureq

( )

tune

Spelling 7

E. The shewa symbol ( ) marks two different shewas, which serve

two functions:

1. The vocal shewa indicates a true shewa, i.e., an inarticulate

vowel sound.

a. The regular vocal shewa is used after consonants except

the gutturals.

EG 1 de / / rm

b. Following a guttural letter, a composite shewa is used.

(1) This sign is also called a reduced vowel or a aep

vowel.

EG 2 / / m

(2) Although there is a composite shewa for each of the

vowel families, the a family is the most common.

NOTE: Gutturals prefer a vowels.

2. The silent shewa is used to mark the empty space after a closed

syllable (see below, 3 A). Words that end with a consonant

do not show a silent shewa at the end, except in the case of

final kap ( ).

EG 3 mi / p

EG 4 mal /

COMPLETE DRILL 1B AND 1C

3 Spelling

A. Syllables

1. All syllables begin with a consonant.

2. Syllables are either open or closed:

a. An open syllable ends in a vowel: Consonant + vowel (Cv)

EG 5 The first syllable of

( / = d / r )

8 Hebrew Chapter 1

b. A closed syllable ends in a consonant: CvC

EG 6 The second syllable of

( / = d / r )

3. As a general rule,

a. an open syllable will have a long vowel;

b. a closed syllable will have a short vowel (but see accent

rules, below, C).

B. Accent

1. The accented syllable (in a multi-syllable word) is called the

tonic syllable (accent = tone).

2. Most words are accented on the final syllable (ultima).

(Such an accent is called milra : from below, i.e., from the

end of the word. Words accented elsewhere than the final

syllable are called mill: from above, i.e., from the beginning

of the word.)

3. For now, accent marks will be used only if the accent is not on

the last syllable.

NOTE: Words are accented on the last syllable unless

otherwise noted.

4. As a general rule,

a. an accented syllable will have a long vowel;

b. an unaccented syllable will have a short vowel (unless it is

also open, see below, C).

C. Summary of vowels and accents in syllables:

1. A syllable that is either open or accented will likely have a long

vowel.

2. A syllable that is both closed and unaccented will (always!)

have a short vowel.

long vowel short vowel

open syllable

or

accented syllable

closed syllable

and

unaccented syllable

Spelling 9

3. A metheg (a secondary accent marked as a short vertical line)

is used to mark an open syllable and to indicate that the vowel

( ) is qame and not qame-aup.

EG 7 = b / re / (h)

not bor / (h)

D. The most significant exception to these principles is the segolate

class of nouns, with an accented first syllable (and a dominance

of the vowel segol). This is due to their historical development

from two-syllable nouns (when Hebrew had case endings) to

monosyllabic nouns and back to two-syllable nouns:

malku malk malk melek = (a family)

sipru sipr sipr sper = (e / i family)

boqru boqr boqr bqer = (o / u family)

COMPLETE DRILL 2

E. Dagesh: There are two dageshes:

1. Dagesh lene hardens a bgdkpt letter (see above, 1 A, p. 3).

This has to do only with pronunciation and not with spelling.

2. Dagesh forte indicates a doubled consonant.

EG 8 is really /

a. Dagesh forte hides a closed syllable with a silent shewa:

EG 9 is really /

cf. = /

NOTE: It is really the first of the two (double) letters (with

its silent shewa) that is written as the dagesh forte.

b. If a dagesh forte falls in a bgdkpt letter, the doubled

consonant will also be pronounced hard. Thus a dagesh

forte in a bgdkpt letter also functions as a dagesh lene.

EG 10 is really /

NOTE: Technically, this should be pronounced di / br,

but in reality, both bgdkpt letters are heard as hard.

10 Hebrew Chapter 1

F. Guttural letters cause some special problems:

1. Guttural letters cannot be doubled. (They will never have a

dagesh forte.)

In this regard, re ( ) acts as a guttural.

2. Guttural letters followed by a vocal shewa will use a composite

shewa in place of the regular shewa.

3. A mappiq (another type of dot) is used to mark a h ( ) that

is used as a consonant instead of as a mater letter.

EG 11 has three consonants, with a short vowel

in the second, closed syllable: g / ah

EG 12 has only two consonants, with a final

mater vowel (in an open syllable): g / (h)

4. Guttural letters generally prefer a family vowels.

a. An a vowel often replaces the expected vowel of a

certain pattern:

EG 13 The segolate noun is of the same pattern

as .

b. A furtive paa usually appears before a final gut-

tural, especially e ( ) or ayin ( ), for the sake of

pronunciation.

EG 14 / la

EG 15 ra

EG 16 n / a

COMPLETE DRILL 3

Spelling 11

Vocabulary, Chapter 1

father (m) king (m)

man, husband (m) justice, judgment (m)

earth (f) boy, lad (m)

son (m) scroll (m)

morning (m) servant, slave (m)

word, thing, matter (m) evening (m)

day (m) Torah, instruction,

law (f)

night (m)

Summary, Chapter 1

I. Consonants

A. bgdkpt letters:

B. Final forms:

C. Gutturals: ()

II. Vowels

A. a / (e) i / (o) u families

B. Short / long / mater letters

C. Shewa

1. Vocal (open syllable, will follow bgdkpt with dagesh

lene)

2. Silent (fills space after a closed syllable and a short vowel,

will follow a bgdkpt without dagesh lene)

III. Spelling

A. Syllables: open and closed

B. Accent: on last syllable unless noted

C. Vowels:

1. Long vowel: open or accented syllable

2. Short vowel: closed and unaccented syllable

D. Dagesh

1. Lene hardens bgdkpt letters.

2. Forte doubles all but gutturals (and re [ ]).

12 Hebrew Chapter 1

Exercises, Chapter 1

Drill 1

A. Practice writing each consonant, including final forms.

1. Learn the name of each letter and the transliteration symbols.

2. Insert dagesh lene in those letters in which it may appear.

3. Know which letters are gutturals.

B. Name each letter and write in transliteration.

(1) (6)

(2) (7)

(3) (8)

(4) (9)

(5) (10)

C. Write in Hebrew letters.

(1) dr (6) k

(2) ym (7) om(h)

(3) khn (8) yelm

(4) (9) arhm

(5) r (10) yirl

Spelling 13

Drill 2

Read out loud, identify each letter (consonants and vowels), and divide

into syllables, noting whether syllables are open or closed:

(1) (6) (11)

(2) (7) (12)

(3) (8) (13)

(4) (9) (14)

(5) (10) (15)

Drill 3

Divide into syllables.

Identify every shewa as silent or vocal.

Identify every dagesh as lene or forte.

(1) (5) (9)

(2) (6) (10)

(3) (7) (11)

(4) (8) (12)

14 Hebrew Chapter 1

Reading Exercise

Practice reading Deuteronomy 5:1:

FUNDAMENTAL

BIBLICAL Aramaic

ANDREW E. STEINMANN

Contents

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

2. Basic Concepts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

3. Phonology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

4. Nouns and Adjectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

5. Prepositions, Pronominal Suffixes, and the Relative Pronoun . . . 300

6. The Verbal System and the G Perfect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306

7. G Perfect: Weak Verbs and Pronominal Suffixes for Verbs . . . . . . . . 310

8. G Imperfect and Jussive: The Strong Verb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315

9. G Imperfect: Weak and Unusual Verbs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

10. G Participle, Imperative, and Infinitive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324

11. Pronouns and Syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 330

12. D Stem: The Strong Verb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335

13. D Stem: Weak Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 339

14. H Stem: The Strong Verb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 343

15. H Stem: Weak and Unusual Verbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 348

16. Reflexive/Passive Conjugations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 353

17. Passive Conjugations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 358

18. Numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361

Appendix: The Strong Verb . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 363

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 365

Topical Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 373

Scripture Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 376

281

Preface

T

he study of the Bible is not truly comprehensive without a knowledge of

Aramaic. While many learn Greek and Hebrew to read the Scriptures

in their original languages, the study of Aramaic, unfortunately, is ofen

neglected. Perhaps the additional efort to learn Aramaic is considered too high a

price to pay to read a few chapters in Ezra and Daniel. Perhaps the limited avail-

ability of instructors trained to teach this biblical language proves problematic.

Tis grammar cannot, by itself, overcome these obstacles. However, it is hoped

that it will make the entire Scriptures more accessible to those who seek to study

Gods Word.

Te goal of this grammar is a modest one: to enable undergraduate and semi-

nary students who possess a working knowledge of biblical Hebrew to obtain

reading profciency in biblical Aramaic. While it is not designed to introduce other

Aramaic dialects, such as Old Aramaic, Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, Palmyrene, or

Nabatean, it is written so the advanced student may continue on to explore other

ancient Aramaic dialects. To that end, periodic references are made to the histori-

cal developments in ancient Aramaic.

To reach the goal of reading profciency, this grammar concentrates on biblical

Aramaic, primarily emphasizing the grammatical features the student will need

to understand. Each of the eighteen chapters can serve as a one-hour lesson for

students who already read Hebrew. Tis allows the student to fnish the grammar

and to read the biblical texts in a typical semester of about ffeen weeks. All the

exercises, with the exception of the beginning exercise in chapter 3, are drawn

directly from the Bible, exposing the student to biblical Aramaic while learning

the grammar. Te only variation from the text is an occasional substitution of a

qer form for a ke form. Te reading of biblical passages will be challenging at

frst and will require the instructor to review the passages with students. However,

such exercises will build student confdence in handling Aramaic. In addition, the

vocabulary introduces all words that occur fve times or more in the Aramaic texts

of the Bible. Words occurring less frequently, but necessary to complete the exer-

cises, are given in the exercises themselves.

Because many students will learn Aramaic only to read the Bible and may

never buy another Aramaic grammar, this grammar is designed not only to be

a teaching tool but also a reference book. Tus the student will fnd a complete

strong verb paradigm in the back of the text, as well as a topical index and an index

to Scripture passages cited in the text or assigned in the exercises.

282 Fundamental Biblical Aramaic

It is hoped that this grammar will be used fruitfully by those who wish to

explore the full counsel of God in the languages that He has used to communicate

His word of Law and Gospel to us.

283

Acknowledgments

I

would like to thank those who have helped produce this book, including stu-

dents who studied Aramaic with me, especially Emily Carder, Ryan Markel,

Kevin Austin, Paul Elliott, Adam Gless, and Aldebaran Schneefock.

I would also like to thank those at Concordia Publishing House who saw this

project through to completion, especially the Rev. Mark Sell, for his vision that a

complete set of grammars for biblical languages is needed for students, and Dawn

Weinstock, who handled many of the production details.

295

4

Nouns and Adjectives

1 Declension of Nouns

A. In Aramaic there is no formal distinction between nouns and

adjectives, though the vowel patterns peil and pail are more closely

associated with adjectives (e.g., frightening; wise).

B. Some patterns in nouns indicate various classes.

pa l profession judges

(cf. Ezra 4:9)

preformative or place dwelling

(cf. Ezra 7:15)

suffixed or abstract concept kingdom

(Dan 5:9, 20, 21)

suffixed (plural ) gentilic noun Chaldeans

(Dan 2:10; 4:4; 5:7)

C. As in Hebrew, nouns and adjectives exist in one of two genders:

masculine or feminine. They also may have three numbers: singular,

dual, and plural.

D. Like Hebrew, the dual is normally reserved for numbers, nouns

denoting time, and items that are thought of as naturally occurring

in pairs. The dual ending for both masculine and feminine nouns

and adjectives is ( for dual determined nouns, see 2). Only

a few duals are used in biblical Aramaic. They are:

two thousand (ke)

(two) hands

the two days

two hundred

(two) feet

(two) horns

the dominion

296 Aramaic Chapter 4

the heavens

(upper and lower sets of) teeth

two (construct state)

two (absolute state)

E. Nouns and adjectives exist in three states in Aramaic: absolute,

construct, and determined. The absolute and construct states are

familiar from Hebrew. The determined state corresponds to the noun

with an article in Hebrew. The endings for these three states are:

Masculine Feminine

singular absolute [none]

construct [none]

determined

plural absolute

construct

determined

It should be noted that the feminine suffix is sometimes spelled

and the determined suffix is sometimes spelled .

The declension of masculine and feminine nouns from the root

is:

Masculine Feminine

singular absolute

construct

determined

plural absolute

construct

determined

Some nouns are feminine but do not show a feminine ending.

Most of these are nouns that naturally come in pairs (e.g.,

hand), though some do not fall into this category (e.g.,

stone). A few nouns and adjectives have irregular plurals:

fathers

Nouns & Adjectives 297

women (singular does not occur in biblical Aramaic)

great

names

2 Determined State of Nouns

Nouns in the determined state are generally equivalent to Hebrew

nouns with the prefixed article. Thus means the king,

means the kings, the queen, and the queens.

Occasionally, Aramaic will use the number (one) to denote lack of

determination. A few examples are:

a letter Ezra 4:8

a scroll Ezra 6:2

a statue Dan 2:31

an hour (a while) Dan 4:16

a stone Dan 6:18

one side Dan 7:5

The determined state also is used for vocatives; thus also can

mean your majesty (O king). Compare the analogous use of

in Hebrew (Judg 3:19; 1 Sam 17:55; 23:20, etc.). Perhaps the most famil-

iar use of the determined state as a vocative is = , which

means Father! (Mark 14:36; Rom 8:15; Gal 4:6).

3 Genitives

A. Construct chains are similar in Aramaic and Hebrew. Occasionally,

the final noun in the chain is indeterminate (in the absolute state),

making all elements of the chain indeterminate (e.g.,

property fine [Ezra 7:26]). More often, however, the final

element in the chain is determinate (i.e., in the determined state,

having a pronominal suffix or a proper noun), making all the

elements in the chain determinate (e.g., the house

of God [Ezra 4:24, etc.]). In general, nothing can interrupt a

construct chain, but some exceptions do exist. Most common is the

use of a construct noun before a prepositional phrase, such as

the kingdoms under all the heavens (Dan 7:27)

298 Aramaic Chapter 4

B. Use of

The genitive relationship may also be expressed in Aramaic by the

use of the relative pronoun (see chapter 5, 3).Two nouns in the

determined state are linked by this pronoun, forming the equiva-

lent of a construct chain. Thus

lions den (construct chain)

lions den (use of ; lit. the den that is

the lions )

4 Adjectival Modification

Adjectives decline in both genders and in all three states. As in Hebrew,

attributive adjectives follow the noun that they modify. Predicate adjec-

tives are always in the absolute state and may precede or follow the

noun they modify. They will agree in number and gender (but not nec-

essarily in state).

Vocabulary, Chapter 4

god; God (when this

Aramaic word is plural, it

always refers to pagan gods)

temple, palace

wise

furnace lord

Babylon fire

, interior bronze, copper

relative pronoun iron

decree, law great; much, many; very

(m),

(f)

one heaven, sky

Nouns & Adjectives 299

Exercises, Chapter 4

Translate

(Dan 2:47) (1)

(Dan 2:47) (2)

(Ezra 5:13) (3)

(Ezra 6:3) (4)

(Dan 4:7) (5)

(Dan 3:6) (6)

(Ezra 5:14) (7)

(Dan 2:18) (8)

(Dan 5:8) (9)

(Dan 2:32) (10)

(Dan 2:31) (11)

(Dan 5:4) (12)

(Ezra 7:12) (13)

You might also like

- Introductory Biblical HebrewDocument98 pagesIntroductory Biblical Hebrewjoabeilon100% (1)

- From Bible To Rabbinic Literature in A NutshellDocument3 pagesFrom Bible To Rabbinic Literature in A NutshelljoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Ancient Hebrew PhonologyDocument20 pagesAncient Hebrew PhonologyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Holman Bible AtlasDocument69 pagesHolman Bible AtlasBea Christian0% (1)

- Torah Hebrew PDFDocument323 pagesTorah Hebrew PDFjoabeilon50% (2)

- Hebrew ResourcesDocument5 pagesHebrew ResourcesjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Thanksgiving in Jewish LiturgyDocument3 pagesThanksgiving in Jewish LiturgyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Uploaded by MistakeDocument1 pageUploaded by MistakejoabeilonNo ratings yet

- From Cuneiform To ABGD - Visual PresentationDocument1 pageFrom Cuneiform To ABGD - Visual PresentationjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewDocument44 pagesThe Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew Bible in S NutshellDocument4 pagesThe Hebrew Bible in S NutshelljoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Mourners KaddishDocument1 pageThe Mourners KaddishjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Letters Vowel Practice Grid Modern Color CodedDocument1 pageHebrew Letters Vowel Practice Grid Modern Color CodedjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- 1) Remained in Ur 2) Left Ur For Haran 2) Left Haran For CanaanDocument1 page1) Remained in Ur 2) Left Ur For Haran 2) Left Haran For CanaanjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyDocument4 pagesLearning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyDocument4 pagesLearning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Near East: Cradle of The JewsDocument37 pagesThe Ancient Near East: Cradle of The JewsjoabeilonNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Us Aers Roadmap Noncontrolling Interest 2019 PDFDocument194 pagesUs Aers Roadmap Noncontrolling Interest 2019 PDFUlii PntNo ratings yet

- Awareness Training On Filipino Sign Language (FSL) PDFDocument3 pagesAwareness Training On Filipino Sign Language (FSL) PDFEmerito PerezNo ratings yet

- Earth-Song WorksheetDocument2 pagesEarth-Song WorksheetMuhammad FarizNo ratings yet

- Ocimum Species Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological ImportanceDocument13 pagesOcimum Species Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological ImportanceManika ManikaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Brief Starting A Small BusinessDocument3 pagesAssignment Brief Starting A Small BusinessFaraz0% (1)

- Dark Matter and Energy ExplainedDocument3 pagesDark Matter and Energy ExplainedLouise YongcoNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Classification GuideDocument32 pagesBiodiversity Classification GuideSasikumar Kovalan100% (3)

- Hannah Money Resume 2Document2 pagesHannah Money Resume 2api-289276737No ratings yet

- A Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFDocument7 pagesA Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFsayeeNo ratings yet

- Elements of Service-Oriented Architecture: B. RamamurthyDocument15 pagesElements of Service-Oriented Architecture: B. RamamurthySaileshan SubhakaranNo ratings yet

- Second Periodic Test - 2018-2019Document21 pagesSecond Periodic Test - 2018-2019JUVELYN BELLITANo ratings yet

- AnovaDocument26 pagesAnovaMuhammad NasimNo ratings yet

- Absolute TowersDocument11 pagesAbsolute TowersSandi Harlan100% (1)

- Compiler Design Lab ManualDocument24 pagesCompiler Design Lab ManualAbhi Kamate29% (7)

- Fs Casas FinalDocument55 pagesFs Casas FinalGwen Araña BalgomaNo ratings yet

- BRM 6Document48 pagesBRM 6Tanu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 78, No. 4, 2020Document199 pagesProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 78, No. 4, 2020Scientia Socialis, Ltd.No ratings yet

- Book of ProtectionDocument69 pagesBook of ProtectiontrungdaongoNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 12Document5 pagesProblem Set 12Francis Philippe Cruzana CariñoNo ratings yet

- Family Health Nursing Process Part 2Document23 pagesFamily Health Nursing Process Part 2Fatima Ysabelle Marie RuizNo ratings yet

- Red ProjectDocument30 pagesRed ProjectApoorva SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- CvSU Vision and MissionDocument2 pagesCvSU Vision and MissionJoshua LagonoyNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Document6 pagesProposal For Funding of Computer Programme (NASS)Foster Boateng67% (3)

- Internal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-MunirDocument53 pagesInternal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-Munirsimone333No ratings yet

- Configure Windows 10 for Aloha POSDocument7 pagesConfigure Windows 10 for Aloha POSBobbyMocorroNo ratings yet

- Letter of Recommendation SamplesDocument3 pagesLetter of Recommendation SamplesLahori MundaNo ratings yet

- Olimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 7 A PDFDocument4 pagesOlimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 7 A PDFAnthony Adams100% (3)

- Cps InfographicDocument1 pageCps Infographicapi-665846419No ratings yet

- Course Syllabus (NGCM 112)Document29 pagesCourse Syllabus (NGCM 112)Marie Ashley Casia100% (1)

- AREVA Directional Over Current Relay MiCOM P12x en TechDataDocument28 pagesAREVA Directional Over Current Relay MiCOM P12x en TechDatadeccanelecNo ratings yet