Professional Documents

Culture Documents

UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6340.501.07s Taught by Monica Rankin (Mar046000)

Uploaded by

UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6340.501.07s Taught by Monica Rankin (Mar046000)

Uploaded by

UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupCopyright:

Available Formats

Course Syllabus

HIST 6340, SEC. 501

MEXICAN REVOLUTION

SPRING 2007, WED, 7:00-9:45, JO 4.708

PROFESSOR CONTACT INFORMATION

Dr. Monica Rankin

JO 5.408

(972) 883-2005

Mobile: (972) 822-5375

mrankin@utdallas.edu

www.utdallas.edu/~mrankin

Office Hours: W 6:00-7:00; TH 11:30-12:30 or by appointment

COURSE DESCRIPTION

The course will examine the nature of Mexico’s 1910 Revolution using a combination of historical

studies, first-hand accounts, and literary accounts. The course will start with an overview of the causes

and course of the revolution, followed by an in-depth consideration of the legacy and meaning of the

revolutionary era. The emphasis will be on how participants and observers of the war molded the

revolution into a movement that took on increasing cultural importance and became intricately linked to

evolving notions of Mexican identity. Focusing on representations of the revolution in various

expressions of popular culture throughout the twentieth-century, we will examine how “revolutionaries”

became legendary icons of greater meaning not only for Mexico, but for U.S. and other foreign observers.

STUDENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES/OUTCOMES

• Students will demonstrate a thorough knowledge of the causes, course, and legacy of the Mexican

Revolution in the twentieth century.

• Students will demonstrate an ability to evaluate the shifting meaning of the Mexican Revolution

in national and international cultural contexts over the course of the twentieth century.

• Students will demonstrate an ability to construct an original research project or historiographical

analysis of a topic relating to Mexican Revolutionary culture.

REQUIRED TEXTBOOKS AND MATERIALS

Weekly Monographs:

Anita Brenner, The Wind that Swept Mexico (University of Texas Press, 1984) ISBN: 0292790244

John Reed, Insurgent Mexico (International Publishers; Reprint edition, 1988) ISBN: 0717800997

Max Parra, Writing Pancho Villa's Revolution: Rebels in the Literary Imagination of Mexico (University

of Texas Press, 2006) ISBN: 0292709781

William Davis, Experiences and Observations of an American Consular Officer During the Mexican

Revolutions (Kessinger Publishing, 2005) ISBN: 1417989211

Martin Luis Guzman, The Eagle and the Serpent (Peter Smith Publisher, 1969) ISBN: 0844606685

Mark Cronlund Anderson, Pancho Villa’s Revolution by Headlines (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000)

ISBN: 0806131721

Course Syllabus Page 1

Elena Poniatowska Here’s to You, Jesusa! (Penguin (Non Classics) 2002) ISBN: 0142001228

John Steinbeck, Zapata (Penguin (Non Classics) 1993) ISBN: 0140173226

Hector Aguilar Camin, In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution: Contemporary Mexican History, 1910-

1989 (University of Texas Press, 1993) ISBN: 0292704518

Recommended:

Adolfo Gilly, The Mexican Revolution (The New Press, 2005) ISBN: 978-1-59558-123-5

Articles and Chapters:

1. James C. Davies, “Toward a Theory of Revolution,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 27, No.

1 (Feb. 1962) pp5-19.

2. Cole Blasier, “Studies of Social Revolution: Origins in Mexico, Bolivia, and Cuba,” Latin

American Research Review, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Summer 1967) pp28-64.

3. Friedrich Katz, “Forward,” in Adolfo Gilly, The Mexican Revolution, (New York: The New

Press, 2005) ppvii-xiv.

4. William D. Raat, “Ideas and Society in Don Porfirio’s Mexico,” The Americas, Vol. 30, No. 1

(Jul. 1973), pp32-53.

5. Steven Bunker, “Consumers of Good Taste: Marketing Modernity in Northern Mexico, 1890-

1910” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Summer 1997) pp227-269.

6. Maria Elena Diaz, “The Satiric Penny Press for Workers in Mexico, 1900-1910: A Case Study in

the Politicisation of Popular Culture,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Oct.

1990) pp497-526.

7. Ann S. Blum, “Conspicuous Benevolence: Liberalism, Public Welfare, and Private Charity in

Porfirian Mexico City, 1877-1910, The Americas, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Jul. 2001), pp7-38.

8. David C. Bailey, “Revisionism and the Recent Historiography of the Mexican Revolution,” The

Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 58-, NO. 1 (Feb. 1978) pp62-79.

9. Paul J. Vanderwood, “Resurveying the Mexican Revolution: Three Provocative New Syntheses

and Their Shortfalls,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Winter 1989) pp145-

163.

10. Alan Knight, “Paul Vanderwood’s Resurveying the Mexican Revolution: A Clarification,”

Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol 6, No. 1 (Winter 1990) pp161-167.

11. Paul Vanderwood, “Paul Vanderwood Responds,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 6,

No. 1 (Winter 1990) p167.

12. Eric Van Young, “Review: Making Leviathan Sneeze: Recent Works on Mexico and the Mexican

Revolution,” Latin American Research Review, Vol. 34, No. 3 (1999) pp143-165.

13. Helen Delpar, “Political Pilgrims in the ‘New Mexico’: Cultural Relations, 1920-1927,” The

Enormous Vogue of Things Mexican (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1992) pp15-54.

Course Syllabus Page 2

14. “Revolution,” The Mexico Reader: History Culture, Politics,” Gilbert M. Joseph et. al (eds.)

(Durham: Duke University Press, 2002) pp333-460.

15. Alan Knight, “The Mexican Revolution: Bourgeois? Nationalist: Or Just a ‘Great Rebellion”?

Bulletin of Latin American Research, Vol. 4, No. 2, (1985) pp1-37.

16. Elizabeth M. Henry, “Revolution as Mexican Novelists See It,” Hispania, Vol. 15, No. 5/6 (Nov.

– Dec. 1932) pp423-436.

17. Beatrice Berler, “The Mexican Revolution as Reflected in the Novel,” Hispania, Vol. 47, No. 1

(March 1965) pp41-46.

18. Ruth Stanton, “Martin Luis Guzman’s Place in Modern Mexican Literature,” Hispania, Vol. 26,

No. 2 (May 1943) pp136-138.

19. Nancy Brandt, “Pancho Villa: The Making of a Modern Legend,” The Americas, Vol. 21, No. 2

(Oct. 1964) pp146-162.

20. Friedrich Katz, “Pancho Villa and the Attack on Columbus, New Mexico,” The American

Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Feb. 1978) pp101-130.

21. Paul J. Vanderwood, “The Picture Postcard as Historical Evidence: Veracruz, 1914,” The

Americas, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Oct. 1988) pp201-225.

22. Merle E. Simmons, “Attitudes toward the United States Revealed in Mexican Corridos,”

Hispania, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Feb. 1953) pp34-42.

23. Victor Alba, “The Mexican Revolution and the Cartoon,” Comparative Studies in Society and

History (Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jan. 1967) pp121-136.

24. Anna Macias “Women and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920,” The Americas, Vol. 37, No. 1

(Jul. 1980) pp53-82.

25. Andres Resendez Fuentes, “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the

Mexican Revolution,” The Americas, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Apr. 1995) pp525-553.

26. Joel Hancock, “Elena Poniatowska’s Hasta no verte Jesus mio: The Remaking of the Image of

Woman,” Hispania, Vol. 66, No. 3 (Sep. 1983) pp353-359.

27. Samuel Brunk, “Remembering Emiliano Zapata: Three Moments in the Posthumous Career of the

Martyr of Chinameca,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Aug. 1998)

pp457-490.

28. Lola E. Boyd, “Zapata in the Literature of the Mexican Revolution,” Hispania, Vol. 52, No. 4

(Dec. 1969) pp903-910.

29. Vincent T. Gawronski, “The Revolution is Dead. “Viva la revolucion!:” The Place of the

Mexican Revolution in the Era of Globalization,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 18,

No. 2 (Summer 2002) pp363-397.

Course Syllabus Page 3

GRADING POLICY

The grading in this course is based on weekly discussions, weekly notes, a presentation, and a final

project. The breakdown of the grading is as follows:

Weekly Notes 20%

Participation 20%

Project Presentation 20%

Final Project 40%

COURSE & INSTRUCTOR POLICIES

No late assignments will be accepted and there is no make-up policy for in-class work.

All assignments for this class are mandatory. Materials used in this course have been carefully selected

for their scholarly value, but some audiences may take offense at topics of a sensitive nature. There will

be NO substitutions of readings, films, documents, presentations, and/or other course requirements to suit

personal preferences. There are NO EXCEPTIONS to this rule.

ASSIGNMENTS

Weekly Notes: You will prepare a reading response for all readings assigned. The papers should include

a statement of the author’s main argument, followed by supporting evidence the author provides. You

should examine the author’s use of sources, methodology, and theory. Your notes should conclude with a

critical analysis of the readings. In your analysis, you should provide your critique of the readings. This

is also where you should include any information you have about the author that may influence your

interpretation of the readings. It is also appropriate to compare your critique to published reviews of the

readings (where available). Peer-reviewed journals publish reviews of many historical monographs, and

these should be available for most books assigned in this course. For literary sources and primary

sources, you should prepare an analytical response emphasizing the historical relevance of the source.

Response papers should be typed and prepared prior to class meetings. You must upload each week’s

paper to WebCT by 7:00 pm every Tuesday to give your classmates an opportunity to read your reaction

to the readings. Based on those reading responses, everyone should prepare a list of 3-5 discussion ideas

and/or question to present to the class. Please bring a paper copy of your notes/reading response to turn in

to me at the end of each class. Since this is a graduate-level reading seminar, I expect your reading

responses to be thorough and to reflect graduate-level analysis. I suggest using the following note-taking

format.

SUGGESTED NOTE-TAKING FORMAT:

• Title/Author: Is there any significance in the title chosen for the work? Who is the author?

What do you know about him/her? Field? Discipline? Institutional affiliation?

Peers/colleagues? For books, was it first a dissertation? What else has the author written?

• Publisher: Who is the publisher? What do you know about the press? Is it academic or

otherwise? What is the publisher known for? What other types of works has the publisher

produced? Is the book part of a series? What is the nature of the series? Who is the series

editor? What do you know about him/her?

• Thesis: What is the author’s main argument (as opposed to the subject of the book)?

• Evidence: How does the author support his/her main argument?

• Research/sources: Look at the notes and bibliography. What primary and secondary sources

did the author consult? Which libraries, collections, archives, etc. were involved?

Course Syllabus Page 4

• Methodology: How did the author approach his/her sources? What questions were asked? Are

any theoretical frameworks involved? Are there any inherent challenges to the sources and/or

approach? How has the author attempted to contend with those challenges?

• Body of Scholarship: Who else has written on the topic? Who else has used similar sources

and/or theoretical models? Where does the work fit within the existing body of literature? It is

responding to a previous study? Was it a seminal work? What have other scholars said about it?

• Critique/analysis: What is your overall critique of the work? Is the thesis solid? Has the author

defended it well? What is your opinion of the use of sources and methodology? How can you

use the information presented? How can you use the methodological model?

Class Participation: This is a graduate readings/research seminar and all students are expected to

participate in class discussions. Approximately half or more of every class meeting will be devoted to

discussing that week’s readings. Please come to class prepared to contribute to a graduate-level

discussion. You should have clear opinions about the week’s readings, authors, topics, etc. You should

review postings on WebCT and prepare yourself accordingly. You may also have questions to pose to the

rest of the class. Class participation is a large portion of your final grade.

Final Project: For the final project in this course, you will select either a research oriented topic or a

historiographical topic dealing with the Mexican Revolution and write a seminar paper due at the end of

the semester. We will periodically discuss potential topics in class and you should contact me early in the

semester to discuss your topic and have it approved. The course schedule includes various progress

report stages where everyone will report on the status of their projects. In the last two weeks of the

semester, you will give an oral presentation of your topic (conference paper style) followed by comments

and questions.

LIBRARY RESOURCES:

Linda Snow, Liaison to the School of Arts and Humanities

snow@utdallas.edu

(972) 883-2626

Library Webpage: www.utdallas.edu/library

TexShare Card: Library card available through the McDermott Library that gives all UTD students

borrower privileges at most university and public libraries throughout the state of Texas.

World Cat: Database of general collections at lending libraries throughout the United States. This

should be the first database you search for sources (primary and secondary) on Latin American history.

World Cat specifies which books are owned by the McDermott Library and includes an inter-library loan

link for books the library does not own.

JSTOR: an electronic archive of core scholarly journals from the humanities, social sciences, and

sciences. The journals have been digitized, starting with their very first issues, often dating back to the

1800s. It does not contain current issues. Everything in JSTOR is full-text. Full-length journals articles

and book reviews can be downloaded on or off campus through the library’s webpage.

Project Muse: a collection of the full text of over 300 high quality humanities, arts, and social sciences

journals from 60 scholarly publishers. Coverage for most journals began around 1995. Full-length

journals articles and book reviews can be downloaded on or off campus through the library’s webpage.

Course Syllabus Page 5

OTHER RESOURCES:

Casahistoria (Documents on the Mexican Revolution):

http://www.casahistoria.net/mexicorevolution.htm#Documents

Primary Documents on the Mexican Revolution (Documents on the web provided by Our Lady of

the Lake University Library):

http://lib.ollusa.edu/netguides/mexico/mexrev.htm#web

Historical Text Archive (Sources on the Mexican Revolution):

http://historicaltextarchive.com/links.php?op=viewslink&sid=224

Robert Runyon Photograph Collection of the South Texas Border Area (Provided by the University

of Texas at Austin Library):

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award97/txuhtml/runyhome.html

Latin American History Links (CSU Ohio):

http://www.csuohio.edu/history/courses/Josehis165/LINKS.htm

Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin:

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/

Revolutionary Mexico in Newspapers (1910-1920) Microfilm collection:

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/revolutionarymexico/

Latin American Network Information Center (LANIC)

http://lanic.utexas.edu/

H-LATAM: Web-based, scholarly discussion network of Latin American historians and other scholars.

This is a good forum for keeping up on current literary debates and also to query experts in the field for

advice on literature, methodology, archives, etc.

http://www.h-net.org/

H-Mexico: H-Net discussion group dedicated to Mexican history and studies. Features subscription

details and reviews

http://www.h-net.org/~mexico/

Gene Z. Hanrahan (ed.) Documents on the Mexican Revolution (3vol, 6parts) (Documentary Publications,

1976-78).

ACADEMIC CALENDAR:

The following schedule outlines the topics and reading assignments for each class. This schedule is

subject to change. Any changes made to the schedule and/or any other course requirements will be

announced in class and will be posted on the course website: www.utdallas.edu/~mrankin.

Course Syllabus Page 6

WEEK 1

Jan. 10 Course Introduction

Lecture: Introduction to the Porfiriato

WEEK 2

Jan. 17 Discussion of Readings

Reserve Readings #s 1-7

Creelman Interview (distributed in class)

Lecture: Introduction to Revolutionary Factions

WEEK 3

Jan. 24 RMLCAS – no class meeting

Work on developing project topics

Reserve Readings #s 8-12

Upload notes/responses to WebCT for virtual discussion

WEEK 4

Jan. 31 Discussion of Readings

Brenner

Reserve Reading #13

Reserve Reading #14 (pp333-350)

Lecture: Overview of Revolutionary Violence

WEEK 5

Feb. 7 Discussion of Readings

Reed

Davis (selected excerpts)

Reserve Reading #15

Reserve Reading #14 (pp387-397)

Presentation of Final Project Topics

WEEK 6

Feb. 14 Discussion of Readings:

Parra

Reserve Readings #s16-17

Presentation of Final Project Topics

WEEK 7

Feb. 21 Discussion of Readings:

Guzman

Reserve Reading #18

Reserve Reading #14 (pp351-363)

FILM: Vamonos con Pancho Villa

Course Syllabus Page 7

WEEK 8

Feb. 28 Discussion of Readings:

Anderson

Davis (selected excerpts)

Reserve Readings #s 19-20

FILM: And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself

WEEK 9

March 14 Discussion of Readings:

Reserve Readings #s21-23

Reserve Reading #14 (pp372-374; 418-420

Final Project Progress Reports

WEEK 10

March 21 Discussion of Readings:

Poniatowska

Reserve Readings #s 24-26

Final Project Progress Reports

Week 11

March 28 Discussion of Readings

Steinbeck

Reserve Readings #s27-28

Reserve Reading #14 (pp375-386)

FILM: Viva Zapata

Week 12

April 4 Discussion of Readings:

Camin

Reserve Reading #29

Reserve Reading #14 (pp411-417; 421-427; 439-455)

Week 13

April 11 Final Project Presentations

Week 14

April 18 Final Project Presentations

April 25 FINAL PROJECT DUE BY 5:00

Course Syllabus Page 8

Student Conduct & Discipline

The University of Texas System and The University of Texas at Dallas have rules and regulations for the orderly and efficient conduct

of their business. It is the responsibility of each student and each student organization to be knowledgeable about the rules and

regulations which govern student conduct and activities. General information on student conduct and discipline is contained in the

UTD publication, A to Z Guide, which is provided to all registered students each academic year.

The University of Texas at Dallas administers student discipline within the procedures of recognized and established due process.

Procedures are defined and described in the Rules and Regulations, Board of Regents, The University of Texas System, Part 1, Chapter

VI, Section 3, and in Title V, Rules on Student Services and Activities of the university’s Handbook of Operating Procedures. Copies

of these rules and regulations are available to students in the Office of the Dean of Students, where staff members are available to

assist students in interpreting the rules and regulations (SU 1.602, 972/883-6391).

A student at the university neither loses the rights nor escapes the responsibilities of citizenship. He or she is expected to obey federal,

state, and local laws as well as the Regents’ Rules, university regulations, and administrative rules. Students are subject to discipline

for violating the standards of conduct whether such conduct takes place on or off campus, or whether civil or criminal penalties are

also imposed for such conduct.

Academic Integrity

The faculty expects from its students a high level of responsibility and academic honesty. Because the value of an academic degree

depends upon the absolute integrity of the work done by the student for that degree, it is imperative that a student demonstrate a high

standard of individual honor in his or her scholastic work.

Scholastic dishonesty includes, but is not limited to, statements, acts or omissions related to applications for enrollment or the award

of a degree, and/or the submission as one’s own work or material that is not one’s own. As a general rule, scholastic dishonesty

involves one of the following acts: cheating, plagiarism, collusion and/or falsifying academic records. Students suspected of

academic dishonesty are subject to disciplinary proceedings.

Plagiarism, especially from the web, from portions of papers for other classes, and from any other source is unacceptable and will be

dealt with under the university’s policy on plagiarism (see general catalog for details). This course will use the resources of

turnitin.com, which searches the web for possible plagiarism and is over 90% effective.

Email Use

The University of Texas at Dallas recognizes the value and efficiency of communication between faculty/staff and students through

electronic mail. At the same time, email raises some issues concerning security and the identity of each individual in an email

exchange. The university encourages all official student email correspondence be sent only to a student’s U.T. Dallas email address

and that faculty and staff consider email from students official only if it originates from a UTD student account. This allows the

university to maintain a high degree of confidence in the identity of all individual corresponding and the security of the transmitted

information. UTD furnishes each student with a free email account that is to be used in all communication with university personnel.

The Department of Information Resources at U.T. Dallas provides a method for students to have their U.T. Dallas mail forwarded to

other accounts.

Withdrawal from Class

The administration of this institution has set deadlines for withdrawal of any college-level courses. These dates and times are

published in that semester's course catalog. Administration procedures must be followed. It is the student's responsibility to handle

withdrawal requirements from any class. In other words, I cannot drop or withdraw any student. You must do the proper paperwork to

ensure that you will not receive a final grade of "F" in a course if you choose not to attend the class once you are enrolled.

Student Grievance Procedures

Procedures for student grievances are found in Title V, Rules on Student Services and Activities, of the university’s Handbook of

Operating Procedures.

In attempting to resolve any student grievance regarding grades, evaluations, or other fulfillments of academic responsibility, it is the

obligation of the student first to make a serious effort to resolve the matter with the instructor, supervisor, administrator, or committee

with whom the grievance originates (hereafter called “the respondent”). Individual faculty members retain primary responsibility for

assigning grades and evaluations. If the matter cannot be resolved at that level, the grievance must be submitted in writing to the

respondent with a copy of the respondent’s School Dean. If the matter is not resolved by the written response provided by the

respondent, the student may submit a written appeal to the School Dean. If the grievance is not resolved by the School Dean’s

decision, the student may make a written appeal to the Dean of Graduate or Undergraduate Education, and the deal will appoint and

convene an Academic Appeals Panel. The decision of the Academic Appeals Panel is final. The results of the academic appeals

process will be distributed to all involved parties.

Course Syllabus Page 9

Copies of these rules and regulations are available to students in the Office of the Dean of Students, where staff members are available

to assist students in interpreting the rules and regulations.

Incomplete Grade Policy

As per university policy, incomplete grades will be granted only for work unavoidably missed at the semester’s end and only if 70%

of the course work has been completed. An incomplete grade must be resolved within eight (8) weeks from the first day of the

subsequent long semester. If the required work to complete the course and to remove the incomplete grade is not submitted by the

specified deadline, the incomplete grade is changed automatically to a grade of F.

Disability Services

The goal of Disability Services is to provide students with disabilities educational opportunities equal to those of their non-disabled

peers. Disability Services is located in room 1.610 in the Student Union. Office hours are Monday and Thursday, 8:30 a.m. to 6:30

p.m.; Tuesday and Wednesday, 8:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m.; and Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

The contact information for the Office of Disability Services is:

The University of Texas at Dallas, SU 22

PO Box 830688

Richardson, Texas 75083-0688

(972) 883-2098 (voice or TTY)

Essentially, the law requires that colleges and universities make those reasonable adjustments necessary to eliminate discrimination on

the basis of disability. For example, it may be necessary to remove classroom prohibitions against tape recorders or animals (in the

case of dog guides) for students who are blind. Occasionally an assignment requirement may be substituted (for example, a research

paper versus an oral presentation for a student who is hearing impaired). Classes enrolled students with mobility impairments may

have to be rescheduled in accessible facilities. The college or university may need to provide special services such as registration,

note-taking, or mobility assistance.

It is the student’s responsibility to notify his or her professors of the need for such an accommodation. Disability Services provides

students with letters to present to faculty members to verify that the student has a disability and needs accommodations. Individuals

requiring special accommodation should contact the professor after class or during office hours.

Religious Holy Days

The University of Texas at Dallas will excuse a student from class or other required activities for the travel to and observance of a

religious holy day for a religion whose places of worship are exempt from property tax under Section 11.20, Tax Code, Texas Code

Annotated.

The student is encouraged to notify the instructor or activity sponsor as soon as possible regarding the absence, preferably in advance

of the assignment. The student, so excused, will be allowed to take the exam or complete the assignment within a reasonable time

after the absence: a period equal to the length of the absence, up to a maximum of one week. A student who notifies the instructor and

completes any missed exam or assignment may not be penalized for the absence. A student who fails to complete the exam or

assignment within the prescribed period may receive a failing grade for that exam or assignment.

If a student or an instructor disagrees about the nature of the absence [i.e., for the purpose of observing a religious holy day] or if there

is similar disagreement about whether the student has been given a reasonable time to complete any missed assignments or

examinations, either the student or the instructor may request a ruling from the chief executive officer of the institution, or his or her

designee. The chief executive officer or designee must take into account the legislative intent of TEC 51.911(b), and the student and

instructor will abide by the decision of the chief executive officer or designee.

Off-Campus Instruction and Course Activities

Off-campus, out-of-state, and foreign instruction and activities are subject to state law and University policies and procedures

regarding travel and risk-related activities. Information regarding these rules and regulations may be found at the website address

given below. Additional information is available from the office of the school dean. (http://www.utdallas.edu/Business

Affairs/Travel_Risk_Activities.htm)

These descriptions and timelines are subject to change at the discretion of the Professor.

Course Syllabus Page 10

You might also like

- UConn Course Explores Mexican PoliticsDocument6 pagesUConn Course Explores Mexican PoliticsgpelaezmNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6360.501.10f Taught by Monica Rankin (Mar046000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6360.501.10f Taught by Monica Rankin (Mar046000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- THE 1960s BALS 2018 RevisedDocument9 pagesTHE 1960s BALS 2018 RevisedhoneromarNo ratings yet

- HI 165 Franz Santos SyllabusDocument5 pagesHI 165 Franz Santos SyllabusBea LegataNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Mexico: Papers of the IV International Congress of Mexican HistoryFrom EverandContemporary Mexico: Papers of the IV International Congress of Mexican HistoryNo ratings yet

- Msem 2011 27 2 449Document22 pagesMsem 2011 27 2 449Ena ChelNo ratings yet

- Syllab Hiw745 2009 FinDocument6 pagesSyllab Hiw745 2009 FinRolando Rios ReyesNo ratings yet

- Spanish Conquest of the AmericasDocument5 pagesSpanish Conquest of the AmericasJorge YanovskyNo ratings yet

- Duke University PressDocument38 pagesDuke University PressJosep Romans FontacabaNo ratings yet

- History, Anthropology and Interdisciplinary DialogueDocument7 pagesHistory, Anthropology and Interdisciplinary DialogueSargam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Paul Strand in Mexico PDFDocument26 pagesPaul Strand in Mexico PDFAdela Pineda FrancoNo ratings yet

- Jia-Chen - Fu@case - Edu: VerviewDocument5 pagesJia-Chen - Fu@case - Edu: VerviewSofia Crespo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Idolatry and Iconoclasm in Revolutionary MexicoDocument35 pagesIdolatry and Iconoclasm in Revolutionary MexicorenatebeNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Propaganda Movement and Noli Me TangereDocument6 pagesRizal's Propaganda Movement and Noli Me TangereNHELBY VERAFLORNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Culture SyllabusDocument5 pagesSociology of Culture Syllabusgaius014No ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist3377.001.09s Taught by Daniel Wickberg (Wickberg)Document9 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Hist3377.001.09s Taught by Daniel Wickberg (Wickberg)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- (Studies of The Americas) Matthew Butler (Eds.) - Faith and Impiety in Revolutionary Mexico-Palgrave Macmillan US (2007)Document298 pages(Studies of The Americas) Matthew Butler (Eds.) - Faith and Impiety in Revolutionary Mexico-Palgrave Macmillan US (2007)Alfredo BadilloNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Introduction To Anthropology 2004 PDFDocument8 pagesSyllabus Introduction To Anthropology 2004 PDFAditya SanyalNo ratings yet

- 1213 Pol2351h1f l0101-NBDocument4 pages1213 Pol2351h1f l0101-NBS-ndyNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - Democracy Security and Migration in The AmericasDocument18 pagesSyllabus - Democracy Security and Migration in The AmericasKevin NesbittNo ratings yet

- CV Hayden WhiteDocument21 pagesCV Hayden WhiteAtila BayatNo ratings yet

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México University of California Institute For Mexico and The United StatesDocument23 pagesUniversidad Nacional Autónoma de México University of California Institute For Mexico and The United StatesAlejandro OliveiraNo ratings yet

- History 667: Problems in Cultural HistoryDocument11 pagesHistory 667: Problems in Cultural Historysilvana_seabraNo ratings yet

- Cult Anthro: Theory and EthnographyDocument5 pagesCult Anthro: Theory and Ethnographyyukti mukdawijitraNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist3377.001.11s Taught by Daniel Wickberg (Wickberg)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Hist3377.001.11s Taught by Daniel Wickberg (Wickberg)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Chicanoa Art ICDocument12 pagesChicanoa Art ICjtobiasfrancoNo ratings yet

- HIST360 Winter2011 LeGrandDocument11 pagesHIST360 Winter2011 LeGrandcajuaisNo ratings yet

- Soc 202 Fall 2015 SyllabusDocument7 pagesSoc 202 Fall 2015 SyllabusBasak CanNo ratings yet

- Quillian Syllabus UrbanDocument8 pagesQuillian Syllabus UrbanCristián ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Books: (Love's A Bitch) (Revolution)Document7 pagesBooks: (Love's A Bitch) (Revolution)Renata CastroNo ratings yet

- Anthropology and History Course Explores Disciplinary IntersectionsDocument11 pagesAnthropology and History Course Explores Disciplinary Intersectionsmsteele242185No ratings yet

- Minimalism IcDocument6 pagesMinimalism IcjtobiasfrancoNo ratings yet

- Lehman - Hiw 350.2009Document7 pagesLehman - Hiw 350.2009Rolando Rios ReyesNo ratings yet

- List of Published Writings by Horacio de La CostaDocument17 pagesList of Published Writings by Horacio de La CostaAnton Mercado0% (1)

- Lamont CulturalsociologyagendaDocument7 pagesLamont CulturalsociologyagendaGadowlNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae 2013 HLFDocument16 pagesCurriculum Vitae 2013 HLFRonnie Frederick Vásquez PonceNo ratings yet

- Latino Cultures and Museums BibliographyDocument9 pagesLatino Cultures and Museums BibliographyEugenia PescaruNo ratings yet

- Art and Anticolonialism SyllabusDocument14 pagesArt and Anticolonialism SyllabusXymon ZubietaNo ratings yet

- American Intellectual History SyllabusDocument11 pagesAmerican Intellectual History Syllabuspaleoman8No ratings yet

- SOC 395D: Poverty and Marginality in The Americas: Emerging Problems, Enduring Debates, Ethnographic PerspectivesDocument6 pagesSOC 395D: Poverty and Marginality in The Americas: Emerging Problems, Enduring Debates, Ethnographic PerspectivesAndreaNo ratings yet

- Searching for Madre Matiana: Prophecy and Popular Culture in Modern MexicoFrom EverandSearching for Madre Matiana: Prophecy and Popular Culture in Modern MexicoNo ratings yet

- How Teaching Profession Helps TeachersDocument5 pagesHow Teaching Profession Helps TeachersAzalea NavarraNo ratings yet

- Mexico 1Document4 pagesMexico 1Styler42No ratings yet

- International Relations Theory UCSBDocument13 pagesInternational Relations Theory UCSBHiroaki OmuraNo ratings yet

- SU1140 - Course OutlineDocument4 pagesSU1140 - Course OutlineAnita SharmaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial ReadingsDocument2 pagesTutorial ReadingsJenniferNo ratings yet

- Nation-Building in Latin America: The Andean Republics in Comparative PerspectiveDocument12 pagesNation-Building in Latin America: The Andean Republics in Comparative PerspectiveRolando Rios ReyesNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives in Cultural History - Syllabus - Ata - 598 - Spring - 2009Document5 pagesNew Perspectives in Cultural History - Syllabus - Ata - 598 - Spring - 2009praxishabitusNo ratings yet

- Mary Kay Vaughan1Document38 pagesMary Kay Vaughan1Orisel CastroNo ratings yet

- Leaders of the Mexican American Generation: Biographical EssaysFrom EverandLeaders of the Mexican American Generation: Biographical EssaysNo ratings yet

- BibliografiaDocument23 pagesBibliografiaMiguel GonzálezNo ratings yet

- ¡México, La Patria! - Propaganda and Production During World War IIDocument384 pages¡México, La Patria! - Propaganda and Production During World War IITimoteo AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Mfissell@jhu - Edu Rpackar2@jhmi - Edu: Olonial NowledgeDocument4 pagesMfissell@jhu - Edu Rpackar2@jhmi - Edu: Olonial NowledgeSebastián GuerraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Latin America II: Prof. José L. RéniqueDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Latin America II: Prof. José L. RéniqueRolando Rios ReyesNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6310.001.10f Taught by Eric Schlereth (Exs082000)Document5 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Hist6310.001.10f Taught by Eric Schlereth (Exs082000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- A Bibliography of The Published and Unpublished Works of John Leon SorensonDocument16 pagesA Bibliography of The Published and Unpublished Works of John Leon SorensonO993No ratings yet

- Methods of Art HistoryDocument7 pagesMethods of Art HistoryPablo Muñoz PonzoNo ratings yet

- Caulfield 2001Document42 pagesCaulfield 2001Valentina BravoNo ratings yet

- Exits from the Labyrinth: Culture and Ideology in the Mexican National SpaceFrom EverandExits from the Labyrinth: Culture and Ideology in the Mexican National SpaceNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Arts3367.001.11f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)Document10 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Arts3367.001.11f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Huas6391.501.10f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Huas6391.501.10f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Arts3373.501.11f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Arts3373.501.11f Taught by Greg Metz (Glmetz)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ce3120.105.11f Taught by Tariq Ali (Tma051000)Document4 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ce3120.105.11f Taught by Tariq Ali (Tma051000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.001.11f Taught by Qiongxia Song (qxs102020)Document6 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.001.11f Taught by Qiongxia Song (qxs102020)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For hdcd6315.001.11f Taught by Cherryl Bryant (clb015400)Document6 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For hdcd6315.001.11f Taught by Cherryl Bryant (clb015400)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Opre6271.pjm.11f Taught by James Szot (jxs011100)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Opre6271.pjm.11f Taught by James Szot (jxs011100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ba3361.502.11f Taught by David Ford JR (Mzad)Document13 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ba3361.502.11f Taught by David Ford JR (Mzad)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Opre6372.pjm.11f Taught by James Szot (jxs011100)Document15 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Opre6372.pjm.11f Taught by James Szot (jxs011100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs1336.501.11f Taught by Feliks Kluzniak (fxk083000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cs1336.501.11f Taught by Feliks Kluzniak (fxk083000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Mech4110.101.11f Taught by Mario Rotea (Mar091000)Document4 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Mech4110.101.11f Taught by Mario Rotea (Mar091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ee3120.105.11f Taught by Tariq Ali (Tma051000)Document5 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ee3120.105.11f Taught by Tariq Ali (Tma051000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs6322.501.11f Taught by Sanda Harabagiu (Sanda)Document6 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cs6322.501.11f Taught by Sanda Harabagiu (Sanda)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ob6301.001.11f Taught by David Ford JR (Mzad)Document11 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ob6301.001.11f Taught by David Ford JR (Mzad)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.002.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.002.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs6320.001.11f Taught by Sanda Harabagiu (Sanda)Document5 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cs6320.001.11f Taught by Sanda Harabagiu (Sanda)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs6390.001.11f Taught by Kamil Sarac (kxs028100)Document5 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cs6390.001.11f Taught by Kamil Sarac (kxs028100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.001.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.001.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math1316.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math1316.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology Group0% (1)

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs6390.001.11f Taught by Kamil Sarac (kxs028100)Document5 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cs6390.001.11f Taught by Kamil Sarac (kxs028100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.003.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Atec3351.003.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math2312.001.11f Taught by Manjula Foley (mxf091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cldp3494.001.11f Taught by Shayla Holub (sch052000)Document4 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For cldp3494.001.11f Taught by Shayla Holub (sch052000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Math4301.001.11f Taught by Wieslaw Krawcewicz (wzk091000)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Math4301.001.11f Taught by Wieslaw Krawcewicz (wzk091000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psy2301.001.11f Taught by James Bartlett (Jbartlet, sch052000)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Psy2301.001.11f Taught by James Bartlett (Jbartlet, sch052000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Atec6341.501.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Atec6341.501.11f Taught by Timothy Christopher (Khimbar)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psy2301.hn1.11f Taught by James Bartlett (Jbartlet, sch052000)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Psy2301.hn1.11f Taught by James Bartlett (Jbartlet, sch052000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Teacher Resume 2Document2 pagesTeacher Resume 2api-253136603No ratings yet

- PNU North Luzon Extension Program Aids COVID VictimsDocument2 pagesPNU North Luzon Extension Program Aids COVID VictimsCharissa CalingganganNo ratings yet

- Liste Des Éditeures Scientifiques PrédateursDocument32 pagesListe Des Éditeures Scientifiques Prédateursمولاي أمحمد عكرميNo ratings yet

- Pros2019 PDFDocument249 pagesPros2019 PDFSanjana sNo ratings yet

- Clemen Tablante Form SF5Document16 pagesClemen Tablante Form SF5MelanioNo ratings yet

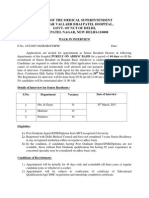

- Office of The Medical Superintendent Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel Hospital, Govt. of NCT of Delhi, East Patel Nagar, New Delhi-110008Document3 pagesOffice of The Medical Superintendent Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel Hospital, Govt. of NCT of Delhi, East Patel Nagar, New Delhi-110008JeshiNo ratings yet

- Sa Maths 2012 (Kadapa Dist)Document4 pagesSa Maths 2012 (Kadapa Dist)Narasimha SastryNo ratings yet

- Maharishi Uni. Jabalpur Fees StructureDocument2 pagesMaharishi Uni. Jabalpur Fees Structuresubbu502No ratings yet

- Https WWW - Lsf.hs-Weingarten - de Qisserver Servlet de - His.servletDocument3 pagesHttps WWW - Lsf.hs-Weingarten - de Qisserver Servlet de - His.servletttNo ratings yet

- Office of The District Education Officer (M-Ee) Jhelum: Check List of Regularization Cases Documents Attached (Yes / No)Document14 pagesOffice of The District Education Officer (M-Ee) Jhelum: Check List of Regularization Cases Documents Attached (Yes / No)Nadeem AfzalNo ratings yet

- UPRA Catalog (2016-2020)Document362 pagesUPRA Catalog (2016-2020)Edwin R. CaballeroNo ratings yet

- PavanDocument2 pagesPavanVenkatsai GadiparthiNo ratings yet

- Fee Structure For The Batch 2014 (Final) - 27 March 2014 PDFDocument12 pagesFee Structure For The Batch 2014 (Final) - 27 March 2014 PDFnavedNo ratings yet

- Unitar Online Catalogue: UOC - UNITAR Master in International Affairs and Diplomacy - Full-Time (March 2022)Document4 pagesUnitar Online Catalogue: UOC - UNITAR Master in International Affairs and Diplomacy - Full-Time (March 2022)Dr YusufNo ratings yet

- Bharathiar University:: Coimbatore - Ph.D. Doctoral Commitiee FormDocument3 pagesBharathiar University:: Coimbatore - Ph.D. Doctoral Commitiee FormBabitha DhanaNo ratings yet

- Interactive Writing ReferencesDocument2 pagesInteractive Writing ReferencesWandi SuwandiNo ratings yet

- Advt. No.7-2020Document11 pagesAdvt. No.7-2020anon_303469603No ratings yet

- Code Volume Chapter XVI Teachers of The UniversityDocument109 pagesCode Volume Chapter XVI Teachers of The UniversityKrishnamohan VaddadiNo ratings yet

- Contoh Format CV Fresh Graduate 2Document1 pageContoh Format CV Fresh Graduate 2Muhammad AzharNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Political Science First Lecture BbaDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Political Science First Lecture BbaAfzaal Mohammad100% (1)

- Data Engineers Inauguration 2019 (Responses) PDFDocument2 pagesData Engineers Inauguration 2019 (Responses) PDFBagoes Rezky RamdhaniNo ratings yet

- Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee Roorkee Rolling Advertisement For Ph.D. Admission 2019-20Document6 pagesIndian Institute of Technology Roorkee Roorkee Rolling Advertisement For Ph.D. Admission 2019-20Nibedita DakuaNo ratings yet

- Calendar of Activities - Ay 2013-2014 - 3rd EdDocument4 pagesCalendar of Activities - Ay 2013-2014 - 3rd EdPrincess Kimberly Ubay-ubayNo ratings yet

- King's College STUDY GUIDE on Turabian citationsDocument12 pagesKing's College STUDY GUIDE on Turabian citationsAlcindorLeadonNo ratings yet

- Pimentel v. Legal Education BoardDocument73 pagesPimentel v. Legal Education BoardChristian Edward CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Arbitral Award WritingDocument2 pagesArbitral Award WritingSyed Imran AdvNo ratings yet

- DGKDocument48 pagesDGKShahbaz Hassan WastiNo ratings yet

- Fulltext1 PDFDocument19 pagesFulltext1 PDFJohn Renheart WacayNo ratings yet

- Velan Nagar, P.V.Vaithiyalingam Road, Pallavaram, Chennai – 600 117Document430 pagesVelan Nagar, P.V.Vaithiyalingam Road, Pallavaram, Chennai – 600 117Bollu SatyanarayanaNo ratings yet

- A0136Document602 pagesA0136RajatPratapSinghNo ratings yet