Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4.2.7. Recommended Good Practices For Vulnerable Populations

Uploaded by

Erika PetersonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

4.2.7. Recommended Good Practices For Vulnerable Populations

Uploaded by

Erika PetersonCopyright:

Available Formats

4.2.7.

Recommended Good Practices for Vulnerable Populations

1 of 2

http://www.microlinks.org/print/3322

Published on USAID Microlinks (http://www.microlinks.org)

Home > 4.2.7. Recommended Good Practices for Vulnerable Populations

4.2.7. Recommended Good Practices for Vulnerable Populations

Pre-Value Chain Selection

Conduct initial situational assessment. Successfully incorporating vulnerable groups into value chain programming requires an understanding of their

skills, risk tolerance and barriers to participation. Practitioners are finding that broad situational assessments (e.g., Household Economy Analysis and CrossSectoral Youth Assessments) yield invaluable information for program design. Given the heterogeneity of vulnerable groups and their varying capacity to

engage in new opportunities, these assessments should analyze individual or household livelihood patterns and distributional patterns within groups, so as to

determine what strategies are most appropriate to the level of vulnerability and what complementary interventions are required to address significant

constraints. The experience of several practitioner organizations suggests that these assessments are best performed prior to performing value chain selection

and value chain analysis, so that these activities are tailored to the capacities and vulnerabilities of the target population.

Value Chain Selection

Expanded criteria. It is critical to select value chain criteria that will facilitate inclusion of vulnerable populations. While the standard criteria are important

to include (competitiveness potential, impact potential, cross-cutting issues, and industry leadership), the selection process also needs to consider the

constraints faced by the target population. Otherwise there is a risk of missing barriers to their participation, or value chains in which they are indirectly

involved. Additional lenses for value chain selection include:

1. Opportunities for employment. Employment offers a lower risk path to benefiting from growing value chains. The interest in self-employment is regularly

over-estimated; often the very vulnerable turn to the informal sector given the lack of attractive alternatives.

2. Minimal potential for harm. Economic opportunities that require long journeys away from home or entry into the public sphere have the potential for

significant harm (see text box below). Value chains should be selected in which these threats are minimal or can be mitigated.

3. Low barriers to entry. Value chains with onerous entry or upgrading requirements are usually inappropriate given limited financial and human capacity.

Multinational and NGO in Ethiopia

One seemingly promising private public partnership between an international agency and an American lead firm created new employment for adolescents as

operators of mobile carts selling soft drink. However, the project was abruptly ended after field workers discovered the young adolescent girls attracted much

greater attention from older men after being brought into the public sphere. This change created extremely detrimental health impacts, as the level of HIV among

the female cart operators jumped dramatically.

Consider cross-cutting or bundles of value chains. Working with the vulnerable as producers of goods or services is often not an appropriate entry point,

given high barriers to entry (e.g., the need to establish vertical linkages, achieve a minimal scale of production, have entrepreneurial ability, invest in

equipment and infrastructure) and the accompanying risks of market fluctuations. Supporting the vulnerable as consumers to improve their access to

products and services that cut across multiple value chains (e.g. irrigation, transport, inputs) are often of greater utility, as many do not produce a surplus or

cannot meet the needs of demanding buyers. This strategy also supports diversificationa common risk mitigation strategy among the vulnerableby not

tying the vulnerable into a single value chain. Rather, they can apply gains (e.g., cheaper or more accessible transportation services) across a range of

domestic and market-oriented activities. Promoting multiple value chains is another strategy to support diversification that reflects the livelihood strategies of

the vulnerable.

Value Chain Analysis

Broaden skill sets. Effectively analyzing the incentives and constraints to upgrading faced by vulnerable populations typically requires the inclusion of

additional expertise in the research team. It is critical to ensure the the strong participation of stakeholders knowledgeable about the vulnerable populations

to be reached through a value chain project, and of representatives of those populations during the value chain analysis process.

Competitiveness Strategy

Adjust project expectations. Project results are often slower than with non-vulnerable populations given the greater number of constraints that are

typically present, particularly at the beginning of a project when trust is weak and risk tolerance is low. Project targets should be adjusted accordingly to

reflect this.

Understand (dis)incentives. Risk aversion, social pressure, lack of confidence, food insecurity, illnesses (e.g., HIV) and other factors shape the incentives

and capacity of vulnerable groups. These incentives are often quite different from those of their less-vulnerable peers. Understanding the range of

non-economic incentives and disincentives to participation and upgrading is important to determine if and how vulnerable groups will engage with value chain

programming.

Design and Implementation

Transitioning from immediate needs. Growth in assets and income is not typically a priority for the most vulnerable. Protecting household assets and

smoothing income flows and consumption patterns may be of greater immediate importance. Working with vulnerable populations often requires support to

address immediate needs while simultaneously developing longer-term livelihood strategies.

Build assets, not over-indebtedness. External finance is a commonly-promoted source of capital for firms to invest in upgrading, particularly from

5/27/2014 1:02 PM

4.2.7. Recommended Good Practices for Vulnerable Populations

2 of 2

http://www.microlinks.org/print/3322

microfinance institutions. For the vulnerable, however, indebtedness often increases vulnerability through the loss of productive assets and social capital.

Generating capital through savings mobilization is generally a preferable strategy.

Avoid targeting when possible. Focusing programming exclusively on a vulnerable group is rarely compatible with building a competitive value chain. The

participation of the less vulnerable builds scale and leverages additional skills and capacity. Projects have more impact when horizontal linkages and other

strategies pull up the vulnerable into wider opportunities. Moreover, taking an inclusive approach avoids stigmatizing or isolating the vulnerable, who from

the perspective of other community members may be perceived as being no different than themselves.

Cardno and the 'Inclusive not Exclusive' Approach

Cardno's Stability, Peace and Reconciliation in Northern Uganda (SPRING) project targets areas of the country that have been previously affected by violence. In

such an environment, targeting specific groups such as ex-combatents, young mothers, orphans has the potential to create significant stigma and resentment

toward targeted groups and even reignite violence. Cardno has therefore adopted an 'inclusive not exclusive' strategy that remains open to the participation of all

groups, while putting in place measures to reach the most vulnerable. One component of this strategy was a 50 percent weighting on value chains that support

stability and social inclusion during the value chain selection process.[1]

Support lower risk activities. Tailor intervention strategies to the limited capacity of vulnerable populations to assume risk. Depending on the level of

vulnerability, options may include:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Developing the market for risk-reducing products and services, including health or life insurance.

Reducing initial cash outlay, such as through embedded services from lead firms.

Looking for potential linkages to lead firms.

Promoting opportunities for employment rather than investment in business start-ups.

Building on existing resources, skills and behaviors, where the vulnerable may already feel confident and that that have comparatively smaller time and

financial investment requirements. If larger changes are required, these should be divided into smaller intermediate steps to promote confidence and reduce

the psychological and financial risk of failure. The figure below presents this graphically.[2]

Recognize the diversity of vulnerability. There are variations in vulnerability within communities and even among the most impoverished. Effective

programs recognize these differences and build diverse entry points into their interventions. For instance, projects may support self-employment

opportunities for individuals with more risk tolerance, while promoting employment and asset building opportunities for those who are more risk adverse.

Take a multi-sectoral approach. The greater constraints faced by vulnerable populations often require using a more diverse set of intervention strategies

and tools to address non-economic constraints. Doing so requires that staff has skills not only in value chains but also in working with the type of vulnerable

population that is being targeted.

Build horizontal linkages to reach markets and develop confidence. Build horizontal linkages among the vulnerable to improve upon weak economies of

scale and to address social issues of empowerment and increasing confidence. These typically informal structures are not always be durable and need not be

structured to be so, but offer an entry point through which quick wins can be generated. Including the non-vulnerable within these structures is often a

powerful strategy to leverage their skills and status while benefiting the less advantaged.

Build market readiness. Vulnerability often limits the capacity and confidence to respond to market incentives. Investing in confidence building, peer

support and market exposure is likely to improve the response of vulnerable populations to value chain interventions. Promoting "quick wins"activities that

can be quickly and easily implemented and that produce immediate (if modest) paybackis especially effective in building confidence, as is supporting peer

demonstrations that prove the potential for success.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Expand measurement frameworks. The process for selection of key performance indicators needs to go beyond traditional metrics for capturing the success

of value chain programming. Measuring intermediate steps that reflect the increased capacity of vulnerable populations to take advantage of value chain

opportunities (e.g. increased self-confidence) is critical to ensure that projects are reaching their intended goals.

Disaggregate project participation. Ensuring the participation of vulnerable groups requires understanding to what extent and under what circumstances

they are active in project interventions. Project monitoring systems that disaggregate reach and performance indicators by type of client will facilitate more

nuanced analysis.

Footnotes

1. N. Felton, Early Lessons Targeting Populations with a Value Chain Approach, (2009), 12-17.

2. J. Wolfe, Household Economic Strengthening in Tanzania: Framework for PEPFAR Programming, (2009), 16.

COMMENTS (0)

5/27/2014 1:02 PM

You might also like

- Hotel Industry - Portfolia AnalysisDocument26 pagesHotel Industry - Portfolia Analysisroguemba87% (15)

- ModificationsDocument118 pagesModificationsErika Peterson100% (1)

- Project Report On WtoDocument81 pagesProject Report On WtoPoonam Saini60% (10)

- Encyclopedia of American BusinessDocument863 pagesEncyclopedia of American Businessshark_freire5046No ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis for Reet in QatarDocument3 pagesSWOT Analysis for Reet in QatarMahrosh BhattiNo ratings yet

- Asa 1202 Unit TwoDocument7 pagesAsa 1202 Unit TwoKAYEMBANo ratings yet

- Session 1 (Handayani) - SP and SPIDocument14 pagesSession 1 (Handayani) - SP and SPIPuti Sari HNo ratings yet

- Final Finance 9aug2017Document7 pagesFinal Finance 9aug2017Elhadji Abdou GUEYENo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Microfinance and Poverty ReductionDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Microfinance and Poverty Reductionea442225No ratings yet

- Financial Inclusion ApproachDocument6 pagesFinancial Inclusion ApproachUnanimous ClientNo ratings yet

- A Methodology For Assessment of The Impact of Microfinance On Empowerment and VulnerabilityDocument42 pagesA Methodology For Assessment of The Impact of Microfinance On Empowerment and VulnerabilityRahul KathaitNo ratings yet

- The Means by Which Poor People Convert Small Sums of Money Into Large Lump Sums (Rutherford 1999)Document7 pagesThe Means by Which Poor People Convert Small Sums of Money Into Large Lump Sums (Rutherford 1999)Ramachandra ReddyNo ratings yet

- Insurance For The PoorDocument38 pagesInsurance For The PooraptureincNo ratings yet

- DFID SusLivAproach GuidanceSheet Section8gloDocument10 pagesDFID SusLivAproach GuidanceSheet Section8gloRabia JamilNo ratings yet

- Finance for Humanitarian Innovation: A Breathtakingly Low 0.27Document38 pagesFinance for Humanitarian Innovation: A Breathtakingly Low 0.27Shruti8589No ratings yet

- Finance Case Study: Ian Gray and Kurt HoffmanDocument38 pagesFinance Case Study: Ian Gray and Kurt HoffmanJanus GalangNo ratings yet

- CGAP Focus Note Microfinance Grants and Non Financial Responses To Poverty Reduction Where Does Microcredit Fit Dec 2002Document12 pagesCGAP Focus Note Microfinance Grants and Non Financial Responses To Poverty Reduction Where Does Microcredit Fit Dec 2002AmituamiNo ratings yet

- Outline - Self Monitoring AgentsDocument4 pagesOutline - Self Monitoring AgentsAditya SarkarNo ratings yet

- 4.2.5. Overview of Very Poor Populations: Analytical Tools For Working With The Very PoorDocument2 pages4.2.5. Overview of Very Poor Populations: Analytical Tools For Working With The Very PoorErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- ZRBF's MEAL FrameworkJuly2016Document31 pagesZRBF's MEAL FrameworkJuly2016Shiela MagnoNo ratings yet

- Habibpura ChetganjPolicy Research Report on Access to FinanceDocument35 pagesHabibpura ChetganjPolicy Research Report on Access to Financeanupam593No ratings yet

- Stakeholder Management and Financial Inclusion StrategiesDocument21 pagesStakeholder Management and Financial Inclusion StrategiesRamakrishnanNo ratings yet

- A Personalised Approach To Safeguards in The NDISDocument21 pagesA Personalised Approach To Safeguards in The NDISThe Centre for Welfare ReformNo ratings yet

- Protection Mainstreaming Tip Sheet - FSL ProgramsDocument3 pagesProtection Mainstreaming Tip Sheet - FSL ProgramsHamidou GarbaNo ratings yet

- Financial InclusionDocument26 pagesFinancial InclusionErick McdonaldNo ratings yet

- Access To Financial Services:: Measurement, Impact and PoliciesDocument41 pagesAccess To Financial Services:: Measurement, Impact and PoliciesRjendra LamsalNo ratings yet

- Dercon Et Al 2004 - Insurance For The Poor1Document34 pagesDercon Et Al 2004 - Insurance For The Poor1aptureincNo ratings yet

- Credit in Developing CountriesDocument28 pagesCredit in Developing CountriesgiovannaprialeNo ratings yet

- STEP UP - Concept Paper Draft Feb 2011Document3 pagesSTEP UP - Concept Paper Draft Feb 2011Poverty Outreach Working Group (POWG)No ratings yet

- Roles of Civil SocietyDocument14 pagesRoles of Civil SocietyMAUREENNo ratings yet

- CGAP Donor Brief The Impact of Microfinance Jul 2003Document2 pagesCGAP Donor Brief The Impact of Microfinance Jul 2003AmituamiNo ratings yet

- Economics of Education Review: Annamaria Lusardi, Pierre-Carl Michaud, Olivia S. MitchellDocument13 pagesEconomics of Education Review: Annamaria Lusardi, Pierre-Carl Michaud, Olivia S. MitchellAnderson PazNo ratings yet

- Targeting RevisitedDocument2 pagesTargeting Revisitedkaps2385No ratings yet

- The Main Risk in FEA in The Situation of Pandemic: Management of Foreign Economic ActivityDocument6 pagesThe Main Risk in FEA in The Situation of Pandemic: Management of Foreign Economic ActivityYulia PekarNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument12 pagesExecutive SummaryZubin PurohitNo ratings yet

- Microinsurance: Literature Review OnDocument37 pagesMicroinsurance: Literature Review OnSandhya NigamNo ratings yet

- Microfinance Thesis ProposalDocument8 pagesMicrofinance Thesis ProposalPapersWritingServiceSingapore100% (2)

- "Microfinance in India An Indepth Study": Project Proposal TitledDocument7 pages"Microfinance in India An Indepth Study": Project Proposal TitledAnkush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Still Too Far To Walk Literature Review of The Determinants of Delivery Service UseDocument5 pagesStill Too Far To Walk Literature Review of The Determinants of Delivery Service Useea4gaa0gNo ratings yet

- SIB SFFedReserveDocument6 pagesSIB SFFedReservear15t0tleNo ratings yet

- Scope: The Future of PIP - A Social Model Based ApproachDocument53 pagesScope: The Future of PIP - A Social Model Based ApproachecdpNo ratings yet

- CSBDF - Moving-the-Needle-Report - 2-2-23 MilesJames - EditsDocument23 pagesCSBDF - Moving-the-Needle-Report - 2-2-23 MilesJames - EditsAdam SaferNo ratings yet

- Ed and Sustainable LivelihoodsDocument10 pagesEd and Sustainable LivelihoodsArjun KauravaNo ratings yet

- Findings From Arnold Ventures' Request For Information On The Dual-Eligible ExperienceDocument10 pagesFindings From Arnold Ventures' Request For Information On The Dual-Eligible ExperienceArnold VenturesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On MicroinsuranceDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Microinsuranceafdtrtrwe100% (1)

- MCN301 M4 - Ktunotes - inDocument29 pagesMCN301 M4 - Ktunotes - inNeerajNo ratings yet

- Localization in Humanitarian ActionDocument4 pagesLocalization in Humanitarian ActionAida JamalNo ratings yet

- CAPACITYDocument1 pageCAPACITYsameerNo ratings yet

- Abvm Gender Chapter Three ppt-1Document41 pagesAbvm Gender Chapter Three ppt-1Alemayehu BantieNo ratings yet

- Deakin Research Online: This Is The Published VersionDocument25 pagesDeakin Research Online: This Is The Published Versionbrentk112No ratings yet

- Financial Inclusion - Issues in Measurement and AnalysisDocument9 pagesFinancial Inclusion - Issues in Measurement and AnalysisKkkkNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On CONTRIBUTION OF MICROFINANCE TOWARD INCLUSIVE GROWTHDocument23 pagesResearch Paper On CONTRIBUTION OF MICROFINANCE TOWARD INCLUSIVE GROWTHRAM MAURYANo ratings yet

- 10 Designing Collective Enterprises Final 3 September 2023Document15 pages10 Designing Collective Enterprises Final 3 September 2023amithembrom64No ratings yet

- Eco-Geo Assignment IDocument11 pagesEco-Geo Assignment INal ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Banking With The PoorDocument8 pagesSustainable Banking With The PoorramiraliNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Impact of MicrofinanceDocument9 pagesLiterature Review On Impact of Microfinancec5pjg3xh100% (1)

- Policy Brief 6Document2 pagesPolicy Brief 6mutaaweNo ratings yet

- Cash Transfer Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesCash Transfer Literature Reviewfrvkuhrif100% (1)

- A Quick Guide To Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning in Fragile ContextsDocument3 pagesA Quick Guide To Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning in Fragile ContextsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyDocument15 pagesMeasurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyKule89No ratings yet

- Cash Transfers Literature Review DfidDocument6 pagesCash Transfers Literature Review Dfidfuhukuheseg2100% (1)

- Research Paper On Financial InclusionDocument57 pagesResearch Paper On Financial InclusionChilaka Pappala0% (1)

- Financial Instruments to Strengthen Women’s Economic Resilience to Climate Change and Disaster RisksFrom EverandFinancial Instruments to Strengthen Women’s Economic Resilience to Climate Change and Disaster RisksNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Management: Critical to Project Success: A Guide for Effective Project ManagersFrom EverandStakeholder Management: Critical to Project Success: A Guide for Effective Project ManagersNo ratings yet

- Using Evidence to Inform Policy: Report of Impact and Policy Conference: Evidence in Governance, Financial Inclusion, and EntrepreneurshipFrom EverandUsing Evidence to Inform Policy: Report of Impact and Policy Conference: Evidence in Governance, Financial Inclusion, and EntrepreneurshipNo ratings yet

- Cochran Alumni Interview Questions-2Document2 pagesCochran Alumni Interview Questions-2Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 4Document10 pages4Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Monthly Timesheet Format: Month /day Working Place Description of Tasks Worked Hours On The ProjectDocument2 pagesMonthly Timesheet Format: Month /day Working Place Description of Tasks Worked Hours On The ProjectErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- SC 3Document1 pageSC 3Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 5 Reg's ThreadDocument7 pages5 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- NFP Rules and RegulationsDocument22 pagesNFP Rules and Regulationsרובֿ טאַלאַנטירט טאַלמידNo ratings yet

- HgehegDocument3 pagesHgehegErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Past Present - Liner NotesDocument10 pagesPast Present - Liner Notesstringbender12No ratings yet

- Example of The Use of Cropwat 8.0Document75 pagesExample of The Use of Cropwat 8.0Iwan100% (8)

- Crop Nutrient Deficiencies - ToxicitiesDocument20 pagesCrop Nutrient Deficiencies - ToxicitiesFarsha Himeros100% (4)

- 2 Reg's ThreadDocument8 pages2 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- A Mod For The Fender Blues JR.: First ImpressionsDocument2 pagesA Mod For The Fender Blues JR.: First ImpressionsErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Scott Peterson Mix RedwirezDocument5 pagesScott Peterson Mix RedwirezErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document41 pagesChapter 4d'chulinsNo ratings yet

- Slash Chords: Triads With A Wrong' Bass Note?: Patrick SchenkiusDocument6 pagesSlash Chords: Triads With A Wrong' Bass Note?: Patrick SchenkiusErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 5 Reg's ThreadDocument7 pages5 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 1 Reg's ThreadDocument10 pages1 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 1 Reg's ThreadDocument10 pages1 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- All RegDocument38 pagesAll RegErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 8Document8 pages8Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 1 Reg's ThreadDocument10 pages1 Reg's ThreadErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 45Document2 pages45Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 4.2.8. ICT For Conflict-Affected Environments: CommentsDocument1 page4.2.8. ICT For Conflict-Affected Environments: CommentsErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 42Document3 pages42Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 4.2.5. Overview of Very Poor Populations: Analytical Tools For Working With The Very PoorDocument2 pages4.2.5. Overview of Very Poor Populations: Analytical Tools For Working With The Very PoorErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 4.2.4. Key Constraints and Promising Strategies in Applying The Value Chain Approach With WomenDocument3 pages4.2.4. Key Constraints and Promising Strategies in Applying The Value Chain Approach With WomenErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- 3.5.7. What Are The Steps in Implementing An Impact Assessment?Document2 pages3.5.7. What Are The Steps in Implementing An Impact Assessment?Erika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Understand Knowledge Flows in Value ChainsDocument1 pageUnderstand Knowledge Flows in Value ChainsErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Chairman, Infosys Technologies LTDDocument16 pagesChairman, Infosys Technologies LTDShamik ShahNo ratings yet

- Total Amount Due: P1,799.00: BIR CAS Permit No. 0415-126-00187 SOA Number: I000051735833Document2 pagesTotal Amount Due: P1,799.00: BIR CAS Permit No. 0415-126-00187 SOA Number: I000051735833Pia Ber-Ber BernardoNo ratings yet

- REFRIGERATORDocument2 pagesREFRIGERATORShah BrothersNo ratings yet

- Marico Over The Wall Operations Case StudyDocument4 pagesMarico Over The Wall Operations Case StudyMohit AssudaniNo ratings yet

- Practical IFRSDocument282 pagesPractical IFRSahmadqasqas100% (1)

- Cover NoteDocument1 pageCover NoteSheera IsmawiNo ratings yet

- Ielts Writing Task 1-Type 2-ComparisonsDocument10 pagesIelts Writing Task 1-Type 2-ComparisonsDung Nguyễn ThanhNo ratings yet

- Practice Problems For Mid TermDocument6 pagesPractice Problems For Mid TermMohit ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Beximco Pharmaceuticals International Business AnalysisDocument5 pagesBeximco Pharmaceuticals International Business AnalysisEhsan KarimNo ratings yet

- Edwin Vieira, Jr. - What Is A Dollar - An Historical Analysis of The Fundamental Question in Monetary Policy PDFDocument33 pagesEdwin Vieira, Jr. - What Is A Dollar - An Historical Analysis of The Fundamental Question in Monetary Policy PDFgkeraunenNo ratings yet

- Current Org StructureDocument2 pagesCurrent Org StructureJuandelaCruzVIIINo ratings yet

- Kanpur TOD Chapter EnglishDocument27 pagesKanpur TOD Chapter EnglishvikasguptaaNo ratings yet

- (Maria Lipman, Nikolay Petrov (Eds.) ) The State of (B-Ok - Xyz)Document165 pages(Maria Lipman, Nikolay Petrov (Eds.) ) The State of (B-Ok - Xyz)gootNo ratings yet

- Dissertation NikhilDocument43 pagesDissertation NikhilSourabh BansalNo ratings yet

- AAEC 3301 - Lecture 5Document31 pagesAAEC 3301 - Lecture 5Fitrhiianii ExBrilliantNo ratings yet

- Ficha Tecnica y Certificado de Bituminoso MartinDocument2 pagesFicha Tecnica y Certificado de Bituminoso MartinPasion Argentina EliuNo ratings yet

- DBBL (Rasel Vai)Document1 pageDBBL (Rasel Vai)anik1116jNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Project Feasibility Study ComponentsDocument2 pagesReal Estate Project Feasibility Study ComponentsSudhakar Ganjikunta100% (1)

- 2020 Retake QuestionsDocument8 pages2020 Retake Questionsayy lmoaNo ratings yet

- Addmaths FolioDocument15 pagesAddmaths Foliomuhd_mutazaNo ratings yet

- Cobrapost II - Expose On Banks Full TextDocument13 pagesCobrapost II - Expose On Banks Full TextFirstpost100% (1)

- Memorandum of Agreement Maam MonaDocument2 pagesMemorandum of Agreement Maam MonaYamden OliverNo ratings yet

- BY Sr. Norjariah Arif Fakulti Pengurusan Teknologi Dan Perniagaan, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia 2 December 2013Document31 pagesBY Sr. Norjariah Arif Fakulti Pengurusan Teknologi Dan Perniagaan, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia 2 December 2013Ili SyazwaniNo ratings yet

- Arjun ReportDocument61 pagesArjun ReportVijay KbNo ratings yet

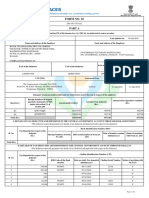

- Form 16 TDS CertificateDocument2 pagesForm 16 TDS CertificateMANJUNATH GOWDANo ratings yet

- Equity vs. EqualityDocument5 pagesEquity vs. Equalityapi-242298926No ratings yet