Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effective Audit Report Writing CPA JOURNAL

Uploaded by

mistercobalt3511Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effective Audit Report Writing CPA JOURNAL

Uploaded by

mistercobalt3511Copyright:

Available Formats

A

& A

auditing

C C O U N T I N G

U D I T I N G

Effective Audit Report Writing

Following the Objective-Based Approach

By Gaurav Kapoor and Connie Valencia

riting an effective audit report

is more of an art than a science.

Although an internal audit

report contains hard facts and requires

internal auditors to maintain their independence and objectivity, it must still deliver a clear message that generates the appropriate reaction. Stakeholders and other

readers of the report should be able to

understand the purpose, value, and results

of the audit within the first few moments

of reading the report. (It is also important

to distinguish between internal audit reports

and the audit report on the financial statements, which is prepared by a companys

independent auditors.)

An effective audit report should engage

the audience, specify and simplify the facts,

and create a call to action. Such a report

must try to answer one main question: why

is the audit report critical? The answer

lies in applying the 80/20 rule, as well as

creating an objective-based audit report

structured around recommendations. A

simplified process, detailed later, can help

internal auditors achieve these objectives.

Although this discussion focuses primarily on internal audit reporting, the

recommendations provided might also be

useful to independent auditors when

addressing internal communication letters

to management. (Such lettersmandated

by Statement on Auditing Standards

[SAS] 115, Communicating Internal

Control Related Matters Identified in an

Auditallow auditors to communicate

information to management regarding

material weaknesses and other deficiencies

noted during an audit.)

The 80/20 Rule

The 80/20 rule essentially states that

20% of input drives 80% of output; thus,

if 80% of a companys revenue comes

36

from 20% of its customers, the company

would naturally want to direct the majority of its efforts and attention toward that

segment. Unfortunately, most auditors find

themselves on the wrong side of the

80/20 rule, where only 20% of their audit

stitutes approximately 20% of the audit

report) is properly communicated, it can

achieve 80% of the buy-in to the recommendations. Consequently, stakeholders

would be more likely to realize the full

value of the conclusions and recommen-

output is reflected in the audit reportthat

is, only 20% of the value of the internal

audit function is reflected in the audit

report. This usually happens because auditors get so tied up in detailed audit findings that they miss the purpose of the audit.

All too often, they forget to tell the story

of why the process needed to be audited,

and thus the question of why the audit matters goes unanswered. Because a sense of

urgency is never created, the recommendations are not implemented and the risks

that triggered the internal audit in the first

place often remain unaddressed.

dations that the auditor presenting the

report brings to the table.

An objective-based audit report continually reinforces the purpose of the audit.

More importantly, it focuses on the audits

observations and answers the question of

why the audit matters. By doing so, the

report focuses on the value of the audit and

greatly increases the chances of the company following through on the auditors

recommendations. The first step in creating an objective-based report is to understand exactly what the key terms in the

report should convey, as described in the

following sections.

Objective. This is the premise and purpose of the report. A meaningful objective creates a connection between the report

and the audience. When identifying the

objective, auditors should ask the several

Creating an Objective-Based

Audit Report

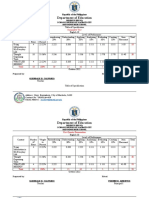

The objective-based approach is depicted in Exhibit 1 as a triangle. It indicates

that if the premise statement (which con-

APRIL 2013 / THE CPA JOURNAL

questions about the report and its audience,

shown in Exhibit 2. For example, the objective of an audit report for Company A

might be to express the opinion that a

newly acquired business unit, which is

material to the business, will not pass the

year-end Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

(SOX) compliance testing. Will the audience take notice? In all probability, they

willespecially, if the company is heavily regulated or publicly traded.

Risk. Anything that threatens the

objective is considered a risk. The risks

identified in the audit report should elicit

a reaction from the audience. When outlining risks, it is important for internal auditors to understand which emotions the

report should generate. In the example

above, a sense of urgency should arise

among Company As stakeholders when

they realize that the newly acquired business entity will be unable to pass the

year-end SOX financial controls testing.

Impact. This is the measurement of the

threat to the objective, and it is where the

call to action is generated. To continue the

previous example, the recommendation

might be to enhance the financial controls

over the newly acquired business entity by

n upgrading to a system that has more

control functionality,

n performing restricted-access reviews, and

n providing training to the accounting

department on how to use the system and

follow the processes more accurately.

and what it was expected to achieve.

Scope statements should identify the

audited activities [content] and include,

where appropriate, supportive information [that describes] the nature and extent

of engagement work performed.

Results should include observations,

conclusions, opinions, recommendations

and action plans.

Introduction. In the introduction, internal auditors should tell the audience exactly what will be discussed in the report. The

most important function of the introduction

is to engage the audience. By illuminating

the impact of the audit observation, the report

can create a sense of urgency among readers; for maximum effectiveness, this should

occur within the first or second line of the

Structuring the Audit Report

As with any professional piece of writing,

an objective-based audit report needs to follow a certain structure. It should have an introduction (a greeting and the reports premise),

a body (the reports main content), and a closing (the reports recommendations and final

review). This format is aligned with the

International Professional Practices

Framework (IPPF) Standard 2410, Criteria

for Communicating Results (http://www.

iadb.org/aug/includes/ProfPracFramework.

pdf). This standard states that all final engagement communications should contain, at a

minimum, the purpose, scope, and results.

The related Practice Advisory 2410-1,

Communication Criteria, goes on to state:

Purpose statements should describe the

engagements objectives [premise] and

may, where necessary, inform the reader why the engagement was conducted

APRIL 2013 / THE CPA JOURNAL

37

audit report. In the example of Company

A, the introduction to the report could start

by saying, Based on the significant weaknesses identified as a result of this audit,

we believe the company will not pass our

2011 SOX evaluation.

With that one statement as the premise,

the audit report will engage the audiences attention and will most likely establish a sense of urgency. Immediately, readers will want to know how the auditor

arrived at this conclusion. The next step

should be to support this bold conclusion

with specific examples. In the case of

Company A, the audit report can state,

Specifically, during our audit, we found

a lack of financial and operational controls

over the following processes:

n Purchasing process. Purchase requisitions do not have supervisor approval.

Purchase orders are not sequentially

numbered or monitored for duplicate

orders.

n Disbursement process. Cash disbursement process does not follow corporate

policy. No limits for electronic cash disbursements are established.

n Accounting for property, plant, and equipment (PPE) balances. Initial balances for

PPE are not properly supported. $XXX million, net effect for PPE as of 12/31/2011.

Once the audience is engaged and a

sense of urgency has been created, the natural next step is to provide solutions to

the specific problems identified. This is

where the content of the report begins.

EXHIBIT 1

The Objective-Based Approach

80%

I. Intro

II. Content

cify

Spe

Eng

age

20%

III. Recommendation

Action

EXHIBIT 2

Knowing the Audience

The following are several questions that internal auditors should ask when writing

their reports:

n

Who should read and who is reading this report?

How much do they know about the subject?

Why should they care about the audit results?

What kind of reaction is the report looking to incite?

38

Body and content. If the introduction is

where internal auditors tell the audience

what the report will discuss, then the

content section of the report is where the

auditors should explain that information.

This represents the meat of the report

and should constitute a majority of the text.

It should explain the relationship between

the causes and effects of the findings,

while simplifying and specifying the facts.

The more specific the facts are in the content of the report, the more credible the

report and recommendations will be.

In the example of Company A, the

content section would explain exactly and

specifically where and how the companys

controls broke down. Examples are the

most effective way to communicate facts

and evidence that support the initial

premise statement.

Recommendations and closing. The recommendations section is where 80% of the

results come shining through. This is where

auditors repeat the information that theyve

conveyed in the report. In other words, this

is where the premise statement is summarized and the call to action is established.

For Company A, the recommendation

section must offer a step-by-step solution

detailing how the company can remediate

the failed controls and ensure compliance

by the end of the year. An executive

audience generally prefers such recommendations when they address specific,

quantifiable savings or when they provide

revenues or profit-enhancing initiatives.

Tips for Creating an Audit Report

The following techniques can aid internal auditors in crafting their reports:

n Define the purpose of the report.

n Only include important and directly

relevant information.

n Simplify the facts; start off with a clear

premise statement.

n Keep sentences and paragraphs short.

n Personalize the pain pointsthat is, the

places where the report identifies the greatest riskby creating a sense of urgency that

can lead to the proper course of action.

n Use the active voice.

n When appropriate, use images to express

conceptsfor example, instead of writing

out financial data, auditors should perhaps insert a chart that displays the relevant balance sheet or income statement

accounts.

APRIL 2013 / THE CPA JOURNAL

Use percentages to express change,

and make sure that a benchmark is established to create meaning and add value to

the percentagefor example, saying that

inventory leakage is at 10% has more value

when the industry average is 7%.

n Know the audience and answer the question of why the report is important.

n

Simplifying and Enhancing

Report Creation

Most auditors struggle with report writing, regardless of the size or range of talent in the audit department. Multiple

types of audit reportsincluding financial audit reports, operational audit reports,

and internal audit reportsneed to be written quickly, simply, and effectively.

Technology can help track the status of

the audit and provide quick access to information when auditors need to refer to audit

results, recommendations, and issues

through centralized information repositories. Standardization of the report-creation

process can make writing audit reports eas-

APRIL 2013 / THE CPA JOURNAL

ier, with specific formats and templates for

multiple types of reports. This allows the

information collected during the audit to

be reported in a consistent manner, using

reports that have a standardized look and

feel. At the same time, the data in the report

can be formatted, downloaded, and exported in various formats. The format can be

structured to have a hard-hitting premise

statement, a comprehensive content section, and a call to action in the recommendations.

Automation of the audit process can provide robust audit trails in order to track

who made changes to which part of the

report and when they did so. Appropriate

stakeholders can be notified when they

have to review an audit or view either the

published draft or the final report.

should make it count by taking the time

to structure the report in an engaging

manner. It might be an independent, factfilled document, but like any piece of

professional writing, it needs to command and sustain the attention of the

reader.

Internal auditors writing such reports

should ensure that the audience is engaged

by creating a strong premise statement that

is well supported by the content (i.e., examples). A sense of urgency and eagerness

should be generated by the report in order

to prepare the audience for the recommendations and solutions provided later.

Lastly, it is important to remember that

technology can simplify and strengthen the

reporting process.

Making the Audit Report Count

Gaurav Kapoor is the chief operating officer of MetricStream Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.

Connie Valencia, CIA, CRMA, and Six

Sigma Yellow Belt, is a principal at

Elevate, Victoria, British Columbia.

The internal audit department is of significant value to any organization. The

primary vehicle for sharing this value is

the audit report; thus, internal auditors

39

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- "Purpose Power Questions": To Unlock Your Purpose Is To Open Your Mind To A Different Set of QuestionsDocument3 pages"Purpose Power Questions": To Unlock Your Purpose Is To Open Your Mind To A Different Set of Questionsmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- FundamentalsofFeedbackFormatted ScottMautz PDFDocument5 pagesFundamentalsofFeedbackFormatted ScottMautz PDFmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Risk-TakingConversationStarters ScottMautz PDFDocument3 pagesRisk-TakingConversationStarters ScottMautz PDFmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- How To Craft A Learning Environment - Part IDocument2 pagesHow To Craft A Learning Environment - Part Imistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Fitness Gym Soft Roller ExercisesDocument11 pagesFitness Gym Soft Roller Exercisesmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- FundamentalsofFeedbackFormatted ScottMautz PDFDocument5 pagesFundamentalsofFeedbackFormatted ScottMautz PDFmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- 5 Musts For Being Mindfully Present: Scott MautzDocument6 pages5 Musts For Being Mindfully Present: Scott Mautzmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- "How To Craft A Learning Environment - Part 2": Scholars Have Long Held ThatDocument2 pages"How To Craft A Learning Environment - Part 2": Scholars Have Long Held Thatmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- How To Avoid Crushing Others Self-ConfidenceDocument3 pagesHow To Avoid Crushing Others Self-Confidencemistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- 10 Insights On Inspirational LeadershipDocument6 pages10 Insights On Inspirational Leadershipmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- 8 Ways To Grant Intelligent AutonomyDocument5 pages8 Ways To Grant Intelligent Autonomymistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Secrets RevealedDocument19 pagesGolf Secrets Revealedcorey turner0% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 10 Insights On Inspirational Leadership: Scott MautzDocument6 pages10 Insights On Inspirational Leadership: Scott Mautzmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 12WaystoKeepYourBestEmployeesFromBoltingMAUTZ PDFDocument4 pages12WaystoKeepYourBestEmployeesFromBoltingMAUTZ PDFmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- 8 Ways To Grant Intelligent AutonomyDocument5 pages8 Ways To Grant Intelligent Autonomymistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 12 Ways To Keep Your Best Employees From BoltingDocument4 pages12 Ways To Keep Your Best Employees From Boltingmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Golf Swing Transition: How To Develop A Great Golf Swing - Part 4Document3 pagesGolf Swing Transition: How To Develop A Great Golf Swing - Part 4mistercobalt35110% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- 5 Musts For Being Mindfully Present: Scott MautzDocument6 pages5 Musts For Being Mindfully Present: Scott Mautzmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Controlled Chipping SetupDocument1 pageControlled Chipping Setupmistercobalt3511100% (1)

- Golf Mickelson Flop ShotDocument1 pageGolf Mickelson Flop Shotmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Ball Striking Drill Description: Moving Up During Backswing And/or DownswingDocument3 pagesBall Striking Drill Description: Moving Up During Backswing And/or Downswingmistercobalt35110% (1)

- 4 Critical Mistakes To Avoid When Looking For Effective Golf Instruction PDFDocument12 pages4 Critical Mistakes To Avoid When Looking For Effective Golf Instruction PDFmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Pitching Set UpDocument1 pageGolf Pitching Set Upmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Golf Chipping Drill For A Consistent StrikeDocument1 pageGolf Chipping Drill For A Consistent Strikemistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Chip Shots From Awkward Lies Part 2Document1 pageGolf Chip Shots From Awkward Lies Part 2mistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Swing Transition: How To Develop A Great Golf Swing - Part 4Document3 pagesGolf Swing Transition: How To Develop A Great Golf Swing - Part 4mistercobalt35110% (1)

- Golf Chip Shots From Awkward Lies Part 2Document1 pageGolf Chip Shots From Awkward Lies Part 2mistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Coaching Setup-CheckpointDocument6 pagesGolf Coaching Setup-Checkpointmistercobalt3511100% (1)

- Golf Coaching Transition-To-Impact-CheckpointsDocument5 pagesGolf Coaching Transition-To-Impact-Checkpointsmistercobalt3511No ratings yet

- Golf Rotation-Follow-Through-CheckpointsDocument4 pagesGolf Rotation-Follow-Through-Checkpointsmistercobalt3511100% (2)

- Roland Barthes and Struggle With AngelDocument8 pagesRoland Barthes and Struggle With AngelAbdullah Bektas0% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Páginas Desdeingles - Sep2008Document1 pagePáginas Desdeingles - Sep2008anayourteacher100% (1)

- Rhodium Catalyzed Hydroformylation - CH 07Document14 pagesRhodium Catalyzed Hydroformylation - CH 07maildesantiagoNo ratings yet

- Appointment Letter JobDocument30 pagesAppointment Letter JobsalmanNo ratings yet

- Failure Reporting, Analysis, and Corrective Action SystemDocument46 pagesFailure Reporting, Analysis, and Corrective Action Systemjwpaprk1No ratings yet

- Companies DatabaseDocument2 pagesCompanies DatabaseNIRAJ KUMARNo ratings yet

- حقيبة تعليمية لمادة التحليلات الهندسية والعدديةDocument28 pagesحقيبة تعليمية لمادة التحليلات الهندسية والعدديةAnjam RasulNo ratings yet

- Dasha TransitDocument43 pagesDasha Transitvishwanath100% (2)

- Antiepilepticdg09gdg 121231093314 Phpapp01Document145 pagesAntiepilepticdg09gdg 121231093314 Phpapp01Vaidya NurNo ratings yet

- Consistency ModelsDocument42 pagesConsistency ModelsPixel DinosaurNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- © Call Centre Helper: 171 Factorial #VALUE! This Will Cause Errors in Your CalculationsDocument19 pages© Call Centre Helper: 171 Factorial #VALUE! This Will Cause Errors in Your CalculationswircexdjNo ratings yet

- 0418 w08 QP 1Document17 pages0418 w08 QP 1pmvarshaNo ratings yet

- Sublime QR CodeDocument6 pagesSublime QR Codejeff_sauserNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ultras 2016 09 002Document11 pages10 1016@j Ultras 2016 09 002Ismahene SmahenoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Electronics & Communication Institute of TechnologyDocument3 pagesPhilippine Electronics & Communication Institute of TechnologyAngela MontonNo ratings yet

- Develop Your Kuji In Ability in Body and MindDocument7 pagesDevelop Your Kuji In Ability in Body and MindLenjivac100% (3)

- Table of Specification ENGLISHDocument2 pagesTable of Specification ENGLISHDonn Abel Aguilar IsturisNo ratings yet

- Platon Si Academia Veche de ZellerDocument680 pagesPlaton Si Academia Veche de ZellerDan BrizaNo ratings yet

- Stereotype Threat Widens Achievement GapDocument2 pagesStereotype Threat Widens Achievement GapJoeNo ratings yet

- Gpredict User Manual 1.2Document64 pagesGpredict User Manual 1.2Will JacksonNo ratings yet

- RBI and Maintenance For RCC Structure SeminarDocument4 pagesRBI and Maintenance For RCC Structure SeminarcoxshulerNo ratings yet

- Date ValidationDocument9 pagesDate ValidationAnonymous 9B0VdTWiNo ratings yet

- The History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle NightingaleDocument21 pagesThe History of American School Libraries: Presented By: Jacob Noodwang, Mary Othic and Noelle Nightingaleapi-166902455No ratings yet

- Final Thesis Owura Kofi AmoabengDocument84 pagesFinal Thesis Owura Kofi AmoabengKunal AgarwalNo ratings yet

- LuberigthDocument24 pagesLuberigthEnrique BarriosNo ratings yet

- Rolfsen Knot Table Guide Crossings 1-10Document4 pagesRolfsen Knot Table Guide Crossings 1-10Pangloss LeibnizNo ratings yet

- Imports System - data.SqlClient Imports System - Data Imports System PartialDocument2 pagesImports System - data.SqlClient Imports System - Data Imports System PartialStuart_Lonnon_1068No ratings yet

- Applying Ocs Patches: Type Area Topic AuthorDocument16 pagesApplying Ocs Patches: Type Area Topic AuthorPILLINAGARAJUNo ratings yet

- Comparing Social Studies Lesson PlansDocument6 pagesComparing Social Studies Lesson PlansArielle Grace Yalung100% (1)

- CV Raman's Discovery of the Raman EffectDocument10 pagesCV Raman's Discovery of the Raman EffectjaarthiNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesFrom EverandLegal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesNo ratings yet

- Everybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeFrom EverandEverybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersFrom EverandDictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsFrom EverandEssential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- LLC or Corporation?: Choose the Right Form for Your BusinessFrom EverandLLC or Corporation?: Choose the Right Form for Your BusinessRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyFrom EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)