Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alves 2008

Uploaded by

Renan M. BirroCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alves 2008

Uploaded by

Renan M. BirroCopyright:

Available Formats

Hum Ecol (2008) 36:443447

DOI 10.1007/s10745-008-9174-5

Use of Tucuxi Dolphin Sotalia fluviatilis for Medicinal

and Magic/Religious Purposes in North of Brazil

Rmulo R. N. Alves & Ierec L. Rosa

Published online: 31 May 2008

# Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008

Introduction

Sotalia fluviatilis (Gervais 1853) commonly known as the

tucuxi is one of the least known cetacean species. The main

threats that affect the species are directly related to habitat

degradation and loss. The rivers and lakes in which

freshwater cetaceans are found are subject to many, often

intensive, human activities that have caused extensive

habitat degradation and loss (WWF 2006). In Brazil, S.

fluviatilis is associated with highly productive and economically important ecosystems, such as mangroves, bays,

and estuaries. This creates a number of situations for

interactions between the species and activities related to

artisanal fisheries, including incidental captures and competition for common resources (Borobia 1989). The use of

S. fluviatilis obtained from bycatch as food or bait has been

amply recorded in Brazil (Siciliano 1994).

Dolphins are the subject of numerous myths and legends

in South America, and are an integral form of Amazonian

folklore. People believe that a person who kills a pink river

dolphin (Inia geofreensis) will not succeed in killing

anything else afterwards, and will always be punished.

There are also stories of dolphins taking paddles away from

lone canoeists, and also of dolphins helping people whose

boats have capsized by pushing them ashore. There are

R. R. N. Alves (*)

Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Estadual da Paraba,

Av. das Baranas, 351/Campus Universitrio, Bodocong,

58109-753 Campina Grande, Paraba, Brazil

e-mail: romulo_nobrega@yahoo.com.br

I. L. Rosa

Departamento de Sistemtica e Ecologia,

Universidade Federal da Paraba,

58051-900 Joo Pessoa, PB, Brazil

e-mail: ierecerosa@yahoo.com.br

even stories of fishermen training dolphins to help them

fish by steering fish towards them (Lamb 1967). Many

people purportedly believe that dolphins seduce girls and

are the father of all children of unknown paternity, and

some women name dolphins as legally responsible for their

illegitimate children. When women give birth to children

with spina bifida, they blame it on dolphins because the

defect leaves an opening in the head that resembles a

dolphin's blowhole (Morell 1997). Dolphins are often

believed to transform themselves in the early hours of the

night into handsome, young, tall, white men, who are

talented dancers, who, before dawn, jump into the water

and turn into dolphins again (Cravalho 1999). During their

transformation into humans, dolphins are believed to enter

households and paralyze their occupants. At such times,

they are said to engage in sexual intercourse with men or

women, depending on the gender of the dolphin. They

often return to the same household, and the victims become

ill, suffering from loss of appetite, body stiffness, and vocal

aberration. Some people are believed to die from it as a

consequence and their soul is taken to the bottom of the sea

to serve as the dolphin's consort (Cravalho 1999). To

defend themselves from a dolphin's attack people are

advised to draw a cross with garlic under their hammocks,

on the back of their neck, and on their foreheads, in the

belief that dolphins do not like garlic.

To a certain extent, such myths have given dolphins

some protection for many generations, and they are

generally left unmolested by the local people. As noted by

Culik (2004), freshwater dolphins have been protected by

such beliefs from Colombia to southern Brazil as well as in

the Amazon. Nevertheless, myths alone have not been

sufficient to preserve the dolphins.

Despite the lack of records of past or recent commercial

fisheries for Sotalia (IWC 2000), gill nets deployed in the

444

dolphins favored habitats clearly have the potential to

cause significant damage to these species at the population

level, as they have to cetaceans worldwide (Northridge and

Hofman 1999). As pointed by Martin et al.( 2004),

Amazonian dolphins selectively occur in areas known to

be favored for gill net deployment by local fishermen, and

this may explain why entanglement is apparently a common

cause of mortality. Additionally, some are deliberately

hunted for their meat and oil, which are used as fish bait

and as an emulsion to protect boats from water. They are

also occasionally hunted for their body parts, which are

used in traditional medicine.

S. fluviatilis is listed in Appendix I of the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and in

Appendix II of the Convention on Migratory species

(CMS), while Sotalia is considered as insufficiently

known by the IUCN (IUCN 2007). In Brazil, it is

protected under the Federal Law, which prohibits hunting

of any wildlife found in its territory for sale nationally or

internationally (Article 1 Law 5,197 January 3, 1967 and

Article 29 of Law 9,605 February 12, 1998). Despite laws

and treaties, use and trade of the species for medicinal and

magic/religious purposes persist in the country.

In Brazil, mainly in north, there is a market for the eyes,

teeth, and genital organs of the dolphins, which are used as

magical charms. The fat and oil of the skin also are used

commercially and in traditional medicine (Alves et al.

2007). Despite intensive use and commercialization, there

is a general lack of information, which renders difficult

evaluation of the magnitude and impact of the harvesting

and trade on the natural populations.

As part of broader study of medicinal and magic/

religious fauna in Brazil, this note reports aspects of the

use and commercialization of S. fluviatilis for medicinal

and magic/religious purposes in Northern Brazil. The study

was conducted in the City of Belm and in the fishing

community of Pesqueiro Beach, both located in the state of

Par. Human communities in the surveyed areas represent

both African and native populations.

Methods

Our study was carried from September to November 2005

in Belm and Pesqueiro Beach, in Par State, Brazil. Belm

is the capital and the largest city in Par (012721 S and

483016 W). Its population exceeds 1.3 million, making it

the tenth largest city in Brazil. Its metropolitan area has

approximately 2.01 million inhabitants. Belm has

hundreds of outdoor markets and shops selling agricultural

commodities, fish, and a wide range of Amazonian flora

and fauna. One of the regions most famous outdoor

markets is the Ver-O-Peso in the City of Belm, where

Hum Ecol (2008) 36:443447

fruit, fish, meat, herbs, medicinal products, and handicrafts

are sold (Shanley 2003).

Pesqueiro Beach is located in the Municipality of Soure,

on the eastern side of the Maraj Island, which is the largest

fluvial island in the world. Soure encompasses an area of

3,528.7 km2 with a population of 19,195 inhabitants. Cattle

ranching is Soures main economic activity, followed by subsistence fisheries and agriculture (Alves and Santana 2008).

Information on the use and commercialization of S.

fluviatilis for medicinal and magic/religious purposes was

obtained through semistructured interviews, complemented

by unstructured interviews (Huntington 2000), which were

conducted on a one-to-one basis. In the City of Belm,

information was collected through interviews with 38

merchants (19 men and 19 women). Of these, 15 were

owners of religious articles stores, and 23 sold herbs or

roots for medicinal purposes in open markets. In Pesqueiro

Beach, interviews were conducted with 41 inhabitants (23

men and 18 women). Knowledge about medicinal animals

is widespread in fishing communities, chiefly amongst the

elderly (Alves and Rosa 2006, 2007a). Information on the

medicinal use of products of S. fluviatilis in traditional

medicines was collected mainly from the elderly populations, who still retain the major portion of traditional

knowledge in their communities. Species identification was

done through photographs taken during interviews, and

with the aid of taxonomists familiar with the study areas

and with local vernacular names.

Results and Discussion

In Belm, interviewees (n=30) stated that they obtain

specimens or parts of S. fluviatilis through sellers that

periodically bring these products to them, or directly from

fishers that come from rural areas and accidentally captured

dolphins. Besides S. fluviatilis, 14 merchants interviewed in

the city of Belm mentioned products derived from the

Amazon River dolphin (Inia geofreensis) which are traded

for same purposes as S. fluviatilis. All interviewees at

Belm and Pesqueiro Beach reported that dolphins are

harpooned, or killed by blows to their heads while

entangled in nets. Incidental captures seem to be common,

as well as mortality due to collisions with boat engines.

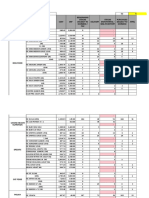

Information on prices and volumes traded is summarized in

Table 1.

Of the 41 interviewees at Pesqueiro Beach, 36 (89%)

reported the use fat and oil of the skin, generally as an

ointment rubbed on a wound or sore place, or swallowed,

depending on the illness to be treated. According to the

interviewees in Belm city (n=15), the fat of S. fluviatilis is

used for treating four diseases: haemorrhoids, rheumatism,

arthrosis and arthritis, being administered in a similar way

Hum Ecol (2008) 36:443447

445

Table 1 Parts and products derived of Sotalia fluviatilis commercialized in Belm City, state of Para

Parts or products

Magic religious use

Amount paid to

supplier (US$)

Sale price (US$)

Volume traded

(monthly)

Vagina

Attract sexual partners,

make money

Attract sexual partners,

make money

Amulets, attract sexual partners,

make money, improve business,

and to bring good luck

Attract sexual partners

US$ 2.3 to 9.0/whole

organ

US$ 1.4 to 4.5/whole

organ

US$ 0.5 to 2.3/unit

US$ 0.9 to 1.4 (a piece),

US$ 6.8 to 22.8 (whole organ)

US$ 0.9 to 1.4 (a piece),

US$ 18 to 27.2 (whole organ)

US$ 3.6 to 13.6/unit

3 to 4 units

Produced using a

penis or vagina

US$ 1.2 to 2.3 (10 ml)

20 to 300 bottles

Penis

Eye

Asseio (dolphin's

perfume)

to that described at Pesqueiro Beach. Dolphins teeth were

also reportedly used in a concoction for treating asthma,

after being sun-dried, grated and crushed to powder.

At Pesqueiro Beach (n=36 interviewees), oil and fat of

the tucuxi dolphin were prescribed for the treatment of 12

diseases (asthma, rheumatism, injuries caused by the spines

of the arraia (stingray) or other fish species, haemorrhoids,

inflammation, wounds, earache, erysipelas (an acute streptococcus bacterial infection of the dermis, resulting in

inflammation and characteristically extending into underlying fat tissue), athletes foot, arthritis (a group of conditions

where there is damage to the joints of the body), cancer and

swelling), while at Belm (n=30 interviewees) the oil and fat

were used for the treatment of three illnesses (haemorrhoids,

rheumatism and arthritis). The much higher number of

conditions quoted at Pesqueiro Beach suggests a broader

knowledge base, focused on the well-being of locals rather

than on trade.

In relation to magic/religious uses, on the other hand,

interviewees at Belem (n=15) provided information on

aspects such as forms of use, while at Pesqueiro Beach the

36 interviewees, despite recognizing the mythic nature of

the dolphin, did not provide detailed information on magic/

religious usesa reflection of links between some traders

and users with Afro-Brazilian religions at Belm. In fact,

two of the interviewees were pais-de-santo and one was a

me-de-santo, respectively, Afro-Brazilian priests and

priestesses of the Yoruba religion known as Candombl,

which according to Voeks (1997), take the role of herbalist,

folk healer, diviner and shaman, as well as that of magician

and sorcerer in Brazil.

Alves and Rosa (2006, 2007a) documented the use of

the fat of S. fluviatilis and S. guianensis for therapeutic

purposes in the states of Piau, Paraba and Maranho, and

these results suggest a geographic continuum in the use of

dolphins as medicine in fishing communities located in

coastal of Brazil, which needs to be further examined in the

context of their conservation and management.

1 to 4 units

10 to 50 units

Beyond their utilization as medicines, parts of S.

fluviatilis are traded for their purported magical/religious

attributes, being popular mainly among adepts of the AfroBrazilian religions. Dolphins products traded are: eyes,

teeth, brain, embryo, penis and vagina. Additionally, these

parts are also used in the preparation of purifying baths

which are indicated for attracting sexual partners. For the

baths, interviewees stated that the water of the

dolphin is prepared using parts of S. fluviatilis (vagina or

penis, according to gender of user) immersed in alcohol or

patchouly oil (Pogostemon sp.). The water also can be

produced using parts of dolphin (penis or vagina) and other

animal species. In one shop in the city of Belm, a

dolphins embryo and the crab Ucides cordatus were used

as ingredients for making the water. The extracts are

subsequently mixed with water during baths, or applied as a

perfume. According to interviewees (n=15), this procedure

will ensure that the user is successful in love-related

matters. Another product indicated to assure the user

success in love is the perfume do boto (dolphins

perfume), also called asseio do (a) boto (a), which is

produced using a penis or vagina of S. fluviatilis. This

product is either used as a perfume or rubbed on the genital

organ prior to intercourse, observing gender distinction:

women should use the product made with the sexual organ

of a female dolphin, while men should use the infusion

containing the sexual organ of a male dolphin.

Our results are in line with some previous studies which

have demonstrated that the dolphins sexual organs are

believed to have special powers. Women grate a dolphin

penis, mix it with talcum powder, and apply it to their vagina

to increase the pleasure they can give a man. A dolphin's

vagina that is grated and applied to a man's penis is believed

to have the same effect (Cravalho 1999). Dolphin parts, such

as eyeballs, genitalia and oil, are increasingly being sold as

aphrodisiacs or medicines throughout their range. This is

especially true in areas with a large influx of new settlers

(Smith 1996; Alves and Rosa 2007b).

446

Another very popular product derived from Sotalia is the

patu, a kind of amulet that is hung around the neck

glued on a piece of cloth, or kept in ones pocket or wallet.

Patus are square or rounded objects, usually made of

leather or some plastic material, containing animal parts

(such as pieces of snake skin or a dolphin eye). Parts of the

dolphins that are used in the patu are: eyes, or pieces of

the penis or vagina. Patus can be produced using one or

more animal parts derived from one or more species of

animal. For example, the same patu can contain a

dolphin eye and a dried seahorse (Hippocampus spp.).

According to the shop owners (n=15) where they are sold,

these amulets are very popular among customers seeking

good luck, love, or financial success.

The use of body parts of dolphins for their magical

power is clearly of some antiquity (Agassiz and Agassiz

1868; Cascudo 1972). A nineteenth-century source mentions that in spite of the respect they have for him as

sorcerer (who at will changes from dolphin to human and

from human to dolphin), still they kill him, to take out the

eyes, the teeth, and the penis, things to all of which they

attribute extraordinary virtues (Cascudo 1972). Beliefs

about dolphins apparently derive from African, European,

and indigenous cultures (Slater 1994), and Brazilian stories

of humans encountering enchanted dolphins have been told

for decades (Cravalho 1999).

Given the volumes traded, and the fact that we did not

carry analyses of the material traded in the two surveyed

localities, we cannot fully discount the possibility that

dolphin eyes were being replaced with other more readily

available products. Nevertheless, Soto and Lessa (2005),

examined a pair of eyes and one penis sold at the Ver-OPeso market, and concluded they indeed belonged to a

small species of dolphin, probably S. fluviatilis.

The demand for dolphin products in local markets may

impact S. fluviatilis populations. However the magnitude

of this impact needs to be further investigated and better

understood. The combination of direct catch, incidental

catch in trawl nets (bycatch), and habitat destruction has

placed dolphin populations at risk. The demand for dolphin

products for use in traditional medicine and for magic/

religious is an additional pressure and should be considered

in conservation and management strategies for those

species. River dolphins are flagship species for their

habitatscharismatic representatives of the biodiversity

within the complex ecosystems they inhabit (Karczmarski

2000; Walpole and Leader-Williams 2002; WWF 2006).

Efforts to safeguard these cetaceans will not only help save

many other species, but will directly contribute to human

development and survival by ensuring the availability of

adequate and clean freshwater (WWF 2006).

Zootherapy is intertwined with sociocultural and

religious beliefs that must be understood by those

Hum Ecol (2008) 36:443447

engaged in modern conservation and protection of

Brazils biodiversity; effective ways to include socioeconomic information and expertise in conservation are

needed. From a biological perspective, there is a need

to increase our understanding of the biology and ecology

of species commonly used as remedies to better assess

the impacts of harvesting them (for medicinal or other

purposes) on their wild populations. Medicinal species

whose conservation status is in question should receive

urgent attention, and aspects such as habitat loss and

alteration should be discussed in connection with present

and future medicinal uses (Alves and Pereira-Filho 2007;

Alves et al. 2007). As Anyinam (1995) remarked,

environmental degradation affects users of traditional

medicine both by limiting their access to the resources

traditionally used, and by diminishing the knowledge

base in their community upon which traditional medicine

is constructed.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the use of the products or parts of

S. fluviatilis is widespread in Northern Brazil, both in urban

and rural areas, reflecting the cultural importance of the

species in the region. Conservation and management plans

are urgently required, but these will have to recognize the

cultural aspects of human communities that use dolphins

for food, medicines or for magic/religious purposes.

Understanding the socioeconomic aspects of use and trade

of dolphins is also important for the development of any

successful management plan. Given that this is the first

report on this subject, further investigations of this topic

may bring important additional information for the conservation of the species.

References

Agassiz, E., and Agassiz, E. C. (1868). A journey in Brazil. Ticknor

and Fields, Boston.

Alves, R. R. N., and Pereira-Filho, G. A. (2007). Commercialization

and use of snakes on North and Northeastern Brazil: implications

for conservation and management. Biodiversity and Conservation

16: 969985.

Alves, R. R. N., and Rosa, I. L. (2006). From cnidarians to mammals:

the use of animals as remedies in fishing communities in NE

Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 107: 259276.

Alves, R. R. N., and Rosa, I. L. (2007a). Zootherapeutic practices

among fishing communities in North and Northeast Brazil: a

comparison. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 111: 83103.

Alves, R. R. N., and Rosa, I. L. (2007b). Zootherapy goes to town: the

use of animal-based remedies in urban areas of NE and N Brazil.

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 113: 541555.

Alves, R. R. N., and Santana, G. G. (2008). Use and commercialization of Podocnemis expansa (Schweiger 1812) (Testudines:

Hum Ecol (2008) 36:443447

Podocnemididae) for medicinal purposes in two communities in

North of Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 4:

3119.

Alves, R. R. N., Rosa, I. L., and Santana, G. G. (2007). The role of

animal-derived remedies as complementary medicine in Brazil.

BioScience 57(11): 949955.

Anyinam, C. (1995). Ecology and ethnomedicine: exploring links

between current environmental crisis and indigenous medical

practices. Social Science & Medicine 40: 321329.

Borobia, M. (1989). Distribution and morphometrics of South

American dolphins Sotalia. 81p. PhD Dissertation, McGill

University, Montreal.

Cascudo, L. C. (1972). Dicionrio de folclore Brasileiro. So Paulo.

Cravalho, M. A. (1999). Shameless creatures: an ethnozoology of the

Amazon river dolphin. Ethnology 38: 14758.

Culik, B. M. (2004). Review of Small Cetaceans: Distribution,

Behaviour, Migration and Threats. Marine Mammal Action

Plan/Regional Seas Reports and Studies, N. 177. Bonn, DEU:

UNEP/CMS Secretariat.

Huntington, H. P. (2000). Using traditional ecological knowledge in

science: methods and applications. Ecological Applications 10:

512701274.

IUCN (2007). 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. www.

iucnredlist.org [accessed 15 January 2007].

IWC, International Whaling Commission (2000). Scientific Committee (2000) Report of the Scientific Sub-Committee on Small

Cetaceans. IWC, Cambridge, UK.

Karczmarski, L. (2000). Conservation and management of humpback

dolphins: the South African perspective. Oryx 34: 3207216.

Lamb, F. B. (1967). The fishermen's porpoise. In Eleanore, D., and

Clark, M. (eds.), The dolphin smile: twenty-nine centuries of

dolphin lore. MacMillan, New York.

447

Martin, A. R., Da Silva, V. M. F., and Salmon, D. L. (2004). Riverine

habitat preferences of botos (Inia geoffrensis) and tucuxis (Sotalia

fluviatilis) in the central Amazon. Marine Mammal Science 20:

2189200.

Morell, V. (1997). Looking for big pink. International Wildlife,

Vienna, Nov/Dec 1997.

Northridge, S. P., and Hofman, R. J. (1999). Marine mamma1

interactions with fisheries. In Twiss, J. R. Jr., and Reeves, R. R.

(eds.), Conservation and management of marine mammals.

Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Shanley, P., and Luz, L. (2003) The impacts of forest degradation on

medicinal plant use and implications for health care in eastern

Amazonia. BioScience 53: 573584

Siciliano, S. (1994) Review of small cetaceans and fishery interactions

in coastal waters of Brazil. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. Special Issue

15. Cambridge, RU.

Slater, C. (1994). The dance of the dolphin. University of Chicago

Press, Chicago.

Smith, A. (1996). The river dolphins: the road to extinction. In

Simmonds, M. P., and Hutchinson, J. D. (eds.), The conservation

of whales and dolphins science and practice. Wiley, New York.

Soto, J. M. R., and Lessa, B. (2005). O comrcio de rgos de tucuxi,

Sotalia fluviatilis (Gervais, 1853) (Cetacea, Delphinidae) na

regio Norte do Brasil. In IV Encontro Nacional sobre Conservao e Pesquisa de Mamferos Aquticos, Itaja (SC).

Voeks, R. A. (1997). Sacred leaves of candombl: African magic,

medicine, and religion in Brazil. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Walpole, M. J., and Leader-Williams, N. (2002). Tourism and flagship

species in conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 11: 543547.

WWF (2006) Species/Freshwater fact sheet: river dolphins. [http://

assets.wwf.ch/downloads/riverdolphinsw.pdf.]. [accessed 15

January 2007].

You might also like

- Beginner S1 #1 Important First Impressions in Brazil: Lesson NotesDocument5 pagesBeginner S1 #1 Important First Impressions in Brazil: Lesson NotesRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Dendroecology of Amazonian tree speciesDocument7 pagesDendroecology of Amazonian tree speciesRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Kin Tigh 2015Document15 pagesKin Tigh 2015Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- A Landscape Converted in M Carver Ed. THDocument16 pagesA Landscape Converted in M Carver Ed. THRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Metraux 1959Document16 pagesMetraux 1959Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Steinforth - Balladoole v.1Document4 pagesSteinforth - Balladoole v.1Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Certificado - CybeleDocument1 pageCertificado - CybeleRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Carl Anderson - Early History of ViaDocument218 pagesCarl Anderson - Early History of Viamarlon1971100% (2)

- Bolin 1953Document36 pagesBolin 1953Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Regna and GentesDocument718 pagesRegna and Genteskalekrtica100% (8)

- $GDSWDQGR 0Dfxqdtpd Sdudrv Dphvprghodjhphsurwrwlsdjhpgh - Rjrv'Ljlwdlvsdud&Lrqfldv6Rfldlvh/Lqjxdjhqvqd (Gxfdomr%IvlfdDocument9 pages$GDSWDQGR 0Dfxqdtpd Sdudrv Dphvprghodjhphsurwrwlsdjhpgh - Rjrv'Ljlwdlvsdud&Lrqfldv6Rfldlvh/Lqjxdjhqvqd (Gxfdomr%IvlfdRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Money Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria A Review of Current DebatesDocument227 pagesMoney Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria A Review of Current DebatesRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- BibliografiaDocument23 pagesBibliografiaRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Author, Jocelin: BiographiesDocument9 pagesAuthor, Jocelin: BiographiesRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Miroslav Hroch-Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe-Cambridge University Press (1985) PDFDocument117 pagesMiroslav Hroch-Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe-Cambridge University Press (1985) PDFRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Mitchell. Reconstructing Old Norse Oral TraditionDocument4 pagesMitchell. Reconstructing Old Norse Oral TraditionRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- HEIZMANN. Die Mythische Vorgeschichte Des Nibelungenhorts PDFDocument34 pagesHEIZMANN. Die Mythische Vorgeschichte Des Nibelungenhorts PDFRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- ENGEN. The Christian Middle Ages As An Historiographical ProblemDocument35 pagesENGEN. The Christian Middle Ages As An Historiographical ProblemRenan M. Birro100% (1)

- Oxford DNB Article - Kermode, Philip Moore CallowDocument2 pagesOxford DNB Article - Kermode, Philip Moore CallowRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- PEIRCE. A Theory of Probable Inference In.. Studies LogicDocument76 pagesPEIRCE. A Theory of Probable Inference In.. Studies LogicRenan M. Birro100% (1)

- Viking Sculpture in CumbriaDocument12 pagesViking Sculpture in CumbriaRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Land or GoldDocument19 pagesLand or GoldRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- 12 Byock ReviewDocument7 pages12 Byock ReviewDaniela RositoNo ratings yet

- The - Historiography - of - A - Construct - Feudalism and Medieval Historian PDFDocument24 pagesThe - Historiography - of - A - Construct - Feudalism and Medieval Historian PDFRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- TURVILLE-PETRE & ROSS (1936) - Agrell's ''Magico-Numerical'' Theory of The Runes. Vol. 47, No. 2Document11 pagesTURVILLE-PETRE & ROSS (1936) - Agrell's ''Magico-Numerical'' Theory of The Runes. Vol. 47, No. 2Renan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- Netgear WGR614v9 Setup ManualDocument36 pagesNetgear WGR614v9 Setup ManualsdinahNo ratings yet

- PEIRCE. Passing Into PoetryDocument34 pagesPEIRCE. Passing Into PoetryRenan M. Birro100% (1)

- COLE, Richard. The French Connection, or Þórr Versus The GolemDocument24 pagesCOLE, Richard. The French Connection, or Þórr Versus The GolemRenan M. BirroNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 200 Best Questions (P-Block Elements)Document31 pages200 Best Questions (P-Block Elements)Tanishq KumarNo ratings yet

- Items FileDocument139 pagesItems FileKzyl Joy CeloricoNo ratings yet

- ABC AIRLINES CASE STUDY Detailed Passenger Analysis and Airline PolicyDocument13 pagesABC AIRLINES CASE STUDY Detailed Passenger Analysis and Airline PolicyBAarunShNo ratings yet

- Love Between LiesDocument254 pagesLove Between LiesBjcNo ratings yet

- GENERAL PHYSICS 2 - Q3 - Week 5Document24 pagesGENERAL PHYSICS 2 - Q3 - Week 5ariinnggg onichaNo ratings yet

- Class6 SyllabusDocument2 pagesClass6 SyllabusMonika SinghalNo ratings yet

- Free Vibration Analysis of Timoshenko Beams UnderDocument16 pagesFree Vibration Analysis of Timoshenko Beams UnderolavusNo ratings yet

- Allen: Modern PhysicsDocument11 pagesAllen: Modern PhysicsOMNo ratings yet

- Quadratic Equations Shortcuts with ExamplesDocument21 pagesQuadratic Equations Shortcuts with ExamplesamitNo ratings yet

- Peran Guru Pendidikan Agama KristenDocument10 pagesPeran Guru Pendidikan Agama KristenAgnes GintingNo ratings yet

- MCT Use Only. Tudent UsrohibitedDocument4 pagesMCT Use Only. Tudent UsrohibitedcnuNo ratings yet

- Mapúa Institute of Technology General Chemistry CourseDocument5 pagesMapúa Institute of Technology General Chemistry CourseMikaella TambisNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Ventilation Made Easy Jaypee PDFDocument97 pagesNeonatal Ventilation Made Easy Jaypee PDFfloare de coltNo ratings yet

- Single ply waterproofing membrane technical data sheetDocument4 pagesSingle ply waterproofing membrane technical data sheetWES QingNo ratings yet

- CBSE CLASS 6 SYLLABUS SUBJECT OVERVIEWDocument9 pagesCBSE CLASS 6 SYLLABUS SUBJECT OVERVIEWAnkita SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- The Geranium Frame With Bullet PointsDocument3 pagesThe Geranium Frame With Bullet Pointso100% (1)

- Theory and Social Research - Neuman - Chapter2Document24 pagesTheory and Social Research - Neuman - Chapter2Madie Chua0% (1)

- 2022 CA Security Assessment and Authorization StandardDocument25 pages2022 CA Security Assessment and Authorization StandardDonaldNo ratings yet

- Dee Christopher - The KnowledgeDocument45 pagesDee Christopher - The Knowledgenikoo1286% (7)

- Kinase InhibitorDocument85 pagesKinase InhibitorSowjanya NekuriNo ratings yet

- LNL Iklcqd /: Grand Total 11,109 7,230 5,621 1,379 6,893Document2 pagesLNL Iklcqd /: Grand Total 11,109 7,230 5,621 1,379 6,893Dawood KhanNo ratings yet

- ISO 27001 Lead Implementer - UdemyDocument1 pageISO 27001 Lead Implementer - UdemyjldtecnoNo ratings yet

- DMart An Ace in Indian Retail SpaceDocument11 pagesDMart An Ace in Indian Retail SpaceSushma Mishra100% (1)

- Calculate Macquarie Uni tuition fees and payment optionsDocument2 pagesCalculate Macquarie Uni tuition fees and payment optionsAsif IqbalNo ratings yet

- Trafficking Body Parts in Mozambique and South Africa Research Report 2010Document80 pagesTrafficking Body Parts in Mozambique and South Africa Research Report 2010simon100% (1)

- ISUZU - Manual Common Rail Motor Isuzu 6DE1-1 PDFDocument35 pagesISUZU - Manual Common Rail Motor Isuzu 6DE1-1 PDFAngelNo ratings yet

- C2 - Tourism Planning Process - FinalDocument56 pagesC2 - Tourism Planning Process - FinalAngel ArcaNo ratings yet

- MinimaxDocument10 pagesMinimaxRitesh Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- Characterization DefinitionDocument3 pagesCharacterization DefinitionAnonymous C2fhhmoNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights Movement Journal Teachers VersionDocument2 pagesCivil Rights Movement Journal Teachers Versionapi-581217100No ratings yet