Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robert McCulloch Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert McCulloch Motion To Dismiss

Uploaded by

Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsCopyright:

Available Formats

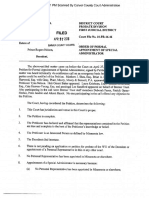

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc.

#: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 1 of 17 PageID #: 108

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI

EASTERN DIVISION

GRAND JUROR DOE,

Plaintiff,

v.

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCH, in his

official capacity as Prosecuting Attorney

for St. Louis County, Missouri,

Defendant.

)

)

)

)

) Case 4:15-cv-6-RWS

)

)

)

)

)

)

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCHS MOTION TO DISMISS

INTRODUCTION

In his Complaint for Prospective Relief, Plaintiff alleges he1 was a member of

the state grand jury tasked with investigating former Ferguson Police Officer

Darren Wilson in the August 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown. Doc. 1 1.

Plaintiff alleges he began his grand jury service in May 2014, and that his term was

extended shortly before its scheduled expiration in September 2014 in order to

investigate Officer Wilson. Doc. 1 10-12. The grand jury ultimately declined to

indict Wilson on any charges, and on November 24, 2014, Plaintiff was discharged

from his grand jury service. Doc. 1 25-26.

Shortly after the grand jury was discharged, Defendant released testimony,

reports, interviews, photographs, and other materials presented to the grand jury

Plaintiff is proceeding in this case under a pseudonym, Grand Juror Doe, and it is unclear from

the Complaint whether Doe is a man or a woman. For the sake of convenience and to avoid

unnecessary confusion, Defendant will use male pronouns in this memorandum to refer to Plaintiff.

1

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 2 of 17 PageID #: 109

during the Wilson investigation pursuant to the Missouri Sunshine Law. Doc. 1

30. The transcripts and documents released by Defendant were redacted to

protect the identities of witnesses and other persons connected to the Wilson

investigation, and no information was released disclosing the names, votes,

opinions, or deliberations of the grand jurors. Doc. 1 30-31 and at Exhibit C.

As a general rule, grand jury investigations in Missouri are kept secret.

Doc. 1 2, 41. Witnesses and others who appear before a grand jury are sworn to

secrecy, and grand jurors are prohibited by law from disclosing their votes,

deliberations, the evidence, or the names of witnesses that appear before them.

Doc. 1 41 (citing Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320, 540.310, 540.080, and 540.120); see

also Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.110 & 540.150. As a grand juror for the St. Louis County

Circuit Court, Plaintiff was subject to Missouri laws governing the scope and terms

of his grand jury service, and he was sworn to keep secret the counsel of the state,

his fellows, and his own. Doc. 1 41 (citing Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.080).

Nevertheless, and despite his obligations under the law and under his oath,

Plaintiff claims he should be freed from any obligation to maintain secrecy, and that

he should be permitted to speak freely about his experiences as a grand juror,

including his perceptions that the presentation of evidence, the behavior of

prosecutors, the focus of the investigation, and the presentation of the law were

handled differently in the Wilson investigation than in the hundreds of other

matters heard by the grand jury. Doc. 1 19-22. Plaintiff believes his experience

as a grand juror could contribute to the current public dialogue concerning race

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 3 of 17 PageID #: 110

relations, and he claims he would like to use his experience to educate the public

and advocate for change in the way grand juries are conducted in Missouri. Doc. 1

34-37.

Although Plaintiff acknowledges "there is a long tradition of grand jury

secrecy," he alleges that under the specific circumstances of this case, continued

secrecy does not advance the interests served by the confidentiality of grand jury

proceedings, and is contrary to Plaintiffs rights under the First Amendment.

Doc. 1 2. Specifically, Plaintiff alleges that because the grand jury has been

discharged and declined to indict Officer Wilson on any charges, there is no risk

the interests furthered by secrecy would be undermined if Plaintiff were allowed to

ignore Missouri law and violate his oath. Doc. 1 45-48.

Plaintiff claims the laws requiring secrecy constitute an impermissible prior

restraint on Plaintiffs rights under the First Amendment, and that he has been

chilled from expressing his individual views and experiences because he fears the

imposition of criminal penalties or other punishments by unnamed government

officials. Doc. 1 40, 57. Plaintiff further claims that the chilling effect is caused

by certain statutes allegedly enforced by Defendant. Doc. 1 41, 50.

Assuming for the sake of argument that Plaintiffs factual allegations are

true, the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs claims. Plaintiff has not alleged sufficient

facts to demonstrate a justiciable case or controversy currently exists between the

parties, and thus, this Court lacks subject matter jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims

under Article III of the Constitution. The claims are also barred by the Eleventh

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 4 of 17 PageID #: 111

Amendment. Further, even if Plaintiffs claims were otherwise ripe for adjudication,

Plaintiff has failed to state a claim upon which relief may be granted. Finally, and

in the alternative should the Court find it has subject matter jurisdiction, the Court

should abstain from exercising jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims because this case

involves important issues of state law that should be decided by a Missouri court.

ARGUMENT

I.

The Court lacks jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1) permits a party to move to dismiss a

complaint for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. Motions to dismiss for lack of

subject-matter jurisdiction can be decided in three ways: at the pleading stage, like

a Rule 12(b)(6) motion; on undisputed facts, like a summary judgment motion; and

on disputed facts. Jessie v. Potter, 516 F.3d 709, 712 (8th Cir. 2008) (citing Osborn

v. U.S., 918 F.2d 724, 72830 (8th Cir. 1990)). Lack of subject matter jurisdiction

cannot be waived, and may be raised at any time by a party to an action or by the

court, sua sponte. Bueford v. Resolution Trust Corp., 991 F.2d 481, 485 (8th Cir.

1993). Once raised, the burden of proving subject matter jurisdiction falls on the

plaintiff. V S Ltd. Pship v. Dept of Housing & Urban Devel., 235 F.3d 1109, 1112

(8th Cir. 2000). Where a plaintiff lacks standing, the district court has no subject

matter jurisdiction. Fabisch v. Univ. of Minn., 304 F.3d 797, 801 (8th Cir. 2002).

In this case, the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs claims for lack of subject

matter jurisdiction because Plaintiff has not alleged sufficient facts to plausibly

establish that he has standing to sue.

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 5 of 17 PageID #: 112

A. Plaintiff lacks standing to assert claims against Defendant.

Article III of the Constitution limits federal courts to adjudicating actual

ongoing cases or controversies. 281 Care Comm. v. Arneson, 638 F.3d 621, 627

(8th Cir. 2011) (citing Republican Party of Minn. v. Klobuchar, 381 F.3d 785, 789

90 (8th Cir. 2004)). A party invoking federal jurisdiction must show a right to

assert a claim in federal court by showing injury in fact, causation, and

redressability. Missouri Roundtable for Life v. Carnahan, 676 F.3d 665, 672 (8th

Cir. 2012) (citing Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560-61 (1992)).

A federal court has subject matter jurisdiction only where an alleged injury

fairly can be traced to the challenged action of the defendant, and not injury that

results from the independent action of some third party not before the court. Simon

v. E. Ky. Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26, 41-42 (1976). Likewise, a party cannot

show an injury in fact by mere allegations of possible future injury. Missouri

Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 672 (quoting Whitmore v. Arkansas, 495 149, 158 (1990)

(punctuation altered from original)). While a party need not expose himself to

actual arrest or prosecution to be entitled to challenge a statute he claims deters his

exercise of constitutional rights, he must show that his injury is more than

imaginary or speculative. Id. (citations and punctuation removed); see also Lujan,

504 U.S. at 560-61; Zanders v. Swanson, 573 F.3d 591, 593-94 (8th Cir. 2009).

In this case, Plaintiff alleges he is chilled from expressing his constitutionally

protected views and experiences because he fears the imposition of criminal

penalties or other punishment by government officials. Doc. 1 40-41, 50. In

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 6 of 17 PageID #: 113

support, Plaintiff points to four Missouri statutes that, according to Plaintiff, are

enforced by Defendant. Doc. 1 41 (citing Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320, 540.310,

540.080 & 540.120). However, a close reading of the statutes cited by Plaintiff

reveals that Plaintiffs purported fears of criminal prosecution by Defendant are

unfounded, and that an injunction entered against Defendant would not redress the

injuries alleged by Plaintiff.

Plaintiff claims that sections 540.320, 540.310, 540.080, and 540.120 are

statutes that Defendant enforces. Doc. 1 41. However, of the four statutes cited

by Plaintiff, only section 540.320 carries criminal penalties enforceable against

grand jurors. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320, 540.310, 540.080, & 540.120. Indeed,

contrary to Plaintiffs allegations, sections 540.080 (Oath of grand jurors) and

540.310 (Cannot be compelled to disclose vote) carry no criminal penalties, and

thus, are not enforceable by Defendant. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.080 & 540.310.

Likewise, although section 540.120 makes it a class B misdemeanor for a witness

before the grand jury to violate the oath administered pursuant to section 540.110,

the statute has nothing to do with enforcing the oath sworn by Plaintiff as a grand

juror under section 540.080. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.120, 540.110, & 540.080.

Given that Defendant lacks authority to prosecute Plaintiff under sections

540.310, 540.080, and 540.120, any injuries stemming from those statutes would not

be redressed if the Court were to enter an injunction against Defendant. See Simon,

426 U.S. at 41-42; see also Wieland v. U.S. Dept of Health & Human Services, 978

F. Supp. 2d 1008, 1014-15 (E.D. Mo. 2013). Indeed, the only statute cited by

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 7 of 17 PageID #: 114

Plaintiff that restricts grand jurors and also carries a criminal penalty enforceable

by Defendant is section 540.320, which makes it a class A misdemeanor for a

grand juror to disclose any evidence given before the grand jury, [or] the name of

any witness who appeared before them, except when lawfully required to testify as

a witness in relation thereto. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320. However, under the

circumstances in this case, Plaintiffs fear that he will be prosecuted for disclosing

evidence or witnesses under section 540.320 is speculative at best, and thus,

insufficient to establish a justiciable case or controversy. See Missouri

Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 672; Zanders, 573 F.3d at 593-94.

Defendant has already released the evidence and testimony given before the

grand jury in the Wilson investigation under the Missouri Sunshine Law, and it is

not objectively reasonable for Plaintiff to believe Defendant will prosecute him for

disclosing the same information. Cf. 281 Care Comm., 638 F.3d. at 631 ([t]he

relevant inquiry is whether a partys decision to chill his speech in light of the

challenged statute is objectively reasonable (quotations omitted)). Indeed, although

the information released by Defendant was redacted to protect the identities of

witnesses and others involved in the investigation, Plaintiff has not alleged that he

wants to disclose any new evidence or reveal the names of any persons that have

not already been publicly identified.

[S]elf-censorship based on mere allegations of a subjective chill resulting

from a statute is not enough to support standing . . . and persons having no fears of

state prosecution except those that are imaginary or speculative, are not to be

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 8 of 17 PageID #: 115

accepted as appropriate plaintiffs. 281 Care Comm., 638 F.3d at 627 (quoting

Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 13-14 (1988), and Babbitt v. United Farm Workers Natl

Union, 442 U.S. 289, 298 (1979)) (punctuation altered from original). Accordingly,

and absent an allegation that Plaintiff plans to disclose evidence or witnesses that

have not previously been disclosed, Plaintiff cannot show he is in any danger of

being prosecuted under section 540.320, and his injuries are insufficiently concrete

to invoke this Courts jurisdiction under Article III. Id.; see also Simon, 426 U.S. at

41-42; Lujan, 504 U.S. at 560-61; Missouri Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 672; Zanders,

573 F.3d at 593-94.

B. Plaintiffs claims against Defendant are not ripe.

In order for a claim to be justiciable, it must be ripe. 281 Care Comm., 638

F.3d at 631. Standing and ripeness are sometimes closely related. Missouri

Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 674 (citing Johnson v. Missouri, 142 F3d 1087, 1090 n.4

(8th Cir. 1998)). Unlike standing, however, ripeness is a prudential doctrine that

permits a court to avoid deciding issues until the facts in the case have become more

fully developed. Id. In assessing ripeness, the inquiry focuses on whether the case

involves contingent future events that may not occur as anticipated, or indeed may

not occur at all. Missouri Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 674 (quotations omitted).

The Court should dismiss Plaintiffs claims against Defendant in this case on

ripeness grounds because Plaintiffs claims depend entirely on contingent events

that may never occur. Indeed, although Plaintiff claims to fear that Defendant will

prosecute him for exercising his First Amendment rights, his fears are unsupported

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 9 of 17 PageID #: 116

by any factual allegations. Plaintiff claims that sections 540.320, 540.310, 540.080,

and 540.120 are statutes that Defendant enforces. Doc. 1 41. However, as

argued above in Part I.A., Defendant lacks authority to prosecute Plaintiff under

sections 540.310, 540.080, and 540.120.

Moreover, although Defendant retains

authority to prosecute Plaintiff under section 540.320, Plaintiffs fears of

prosecution are unreasonable given that Plaintiff has not alleged that he plans to

disclose evidence or witnesses that have not previously been disclosed.

Given that Plaintiffs claims against Defendant depend entirely upon his

alleged fear of a criminal prosecution that may never occur, the Court should

dismiss Plaintiffs claims as unripe. Missouri Roundtable, 676 F.3d at 674.

C. The Eleventh Amendment bars Plaintiffs claims.

The Eleventh Amendment confirms that the fundamental principle of

sovereign immunity limits the grant of judicial authority in Article III. Green v.

Mansour, 474 U.S. 64, 68 (1985). Eleventh Amendment immunity bars actions

against a state for both money damages and equitable relief. Cory v. White, 457 U.S.

85, 90-91 (1982). Although the Supreme Courts decision in Ex Parte Young created

an exception to immunity for suits to prevent state officials from taking illegal

actions, the exception requires a defendant official to have some connection with

the enforcement of the act, or else it is merely making him a party as a

representative of the state, and thereby attempting to make the state a party. Ex

Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123, 157 (1908). Accordingly, [a]bsent a real likelihood that

[a] state official will employ his supervisory powers against plaintiffs interests, the

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 10 of 17 PageID #: 117

Eleventh Amendment bars federal court jurisdiction. 281 Care Comm. v. Arneson,

766 F.3d 774, 797 (8th Cir. 2014) (citing Long v. Van de Kamp, 961 F.2d 151, 152

(9th Cir.1992)); see also Reprod. Health Serv. of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis

Region, Inc. v. Nixon, 428 F.3d 1139, 1145 (8th Cir. 2005).

In this case, as discussed above in Parts I.A. and I.B, Plaintiff has not alleged

or demonstrated a real likelihood that Defendant will employ his powers against

Plaintiffs claimed interests. Accordingly, the Court lacks jurisdiction over Plaintiffs

claims under the Eleventh Amendment. 281 Care Comm., 766 F.3d at 797, Reprod.

Health Serv., 428 F.3d at 1145.

II.

Plaintiff has not stated a claim upon which relief may be granted.

Unlike a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, the facts

alleged in the complaint must be accepted as true on a motion to dismiss pursuant

to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). Schmidt v. Des Moines Pub. Sch., 655

F.3d 811, 815 (8th Cir. 2011). To survive such a motion, a complaint must contain

sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief that is plausible

on its face. . . . A claim has facial plausibility when the plaintiff pleads factual

content that allows the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is

liable for the misconduct alleged. Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009)

(quoting Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 556 (2007)); see also L.L.

Nelson Enter., Inc. v. County of St. Louis, Mo., 673 F.3d 799, 804-05 (8th Cir. 2012).

Plaintiffs purported First Amendment claims against Defendant stem from

his alleged fear that Defendant will prosecute Plaintiff for speaking about his

10

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 11 of 17 PageID #: 118

experiences as a grand juror. However, the only statute cited by Plaintiff that

restricts grand jurors and also carries a criminal penalty enforceable by Defendant

is section 540.320, which prohibits grand jurors from disclosing evidence or the

names of witnesses that appear before them. As argued above, Plaintiff has not

alleged he wishes to disclose any evidence or witnesses that have not already been

disclosed, and thus, his fears of prosecution under section 540.320 are speculative,

and his claims against Defendant are not justiciable. However, assuming for the

sake of argument that Plaintiff does plan to disclose evidence and witnesses that

have not previously been made public, the Court should dismiss his claims for

failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted.

The Grand Jury is an arm of the court and is a body with functions of a

judicial nature. State ex rel. Burke v. Scott, 262 S.W.2d 614, 618 (Mo. banc 1953).

Grand jurors are sworn to secrecy and apprised by the circuit court of their duties

under the law to keep their deliberations and their votes secret. See Mo. Rev. Stat.

540.080 & 540.330. Proceedings before Missouri grand juries are generally held

secret, and the secrecy is intended, among other things, to protect the jurors

themselves; to promote a complete freedom of disclosure; to prevent the escape of a

person indicted before he may be arrested; to prevent the subornation of perjury in

an effort to disprove facts there testified to; and to protect the reputations of

persons against whom no indictment may be found. Mannon v. Frick, 295 S.W.2d

158, 162 (Mo. 1956); see also Palmentere v. Campbell, 205 F. Supp. 261, 264 (W.D.

Mo. 1962).

11

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 12 of 17 PageID #: 119

Although disclosure of grand jury materials may be had when required by the

general public interest or in the protection of private rights, grand jurors are not

permitted to issue reports, and the deliberations, votes, and opinions of grand jurors

are forbidden from disclosure. See In the Matter of Interim Report of the Grand

Jury, 553 S.W.2d 479, 482 (Mo. banc 1977); In the Matter of the Report of the Grand

Jury, 612 S.W.2d 864, 865-66 (Mo. App. E.D. 1981); In the Matter of Regular Report

of Grand Jury, 585 S.W.2d 76, 77 (Mo. App. E.D. 1979); see also Mannon, 295

S.W.2d at 162; Palmentere, 205 F. Supp. at 266 (secrecy imposed upon grand juries

has not been relaxed in respect to what was said and done by grand jurors

themselves in regard to any indictment or matter under investigation).

In this case, Defendant released the testimony, reports, interviews,

photographs, and other materials presented to the grand jury during the Wilson

investigation pursuant to the Missouri Sunshine Law. Doc. 1 30; see also Doc. 1-4.

However, Defendant redacted the materials prior to release in order to protect the

identities of witnesses and other persons involved in the investigation as required

under section 610.100.3. See Doc. 1 at Exhibit C; Doc. 1-4.

Plaintiff alleges that the Supreme Courts decision in Butterworth v. Smith,

410 U.S. 1 (1973), authorizes him to share information that he learned as a grand

juror. Doc. 1 2. However, the Butterworth decision does not support Plaintiffs

position or provide Plaintiff a constitutional justification for violating the

prohibition under section 540.320 against disclosing evidence and witnesses before

the grand jury. Mo. Rev. Stat. 540.320.

12

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 13 of 17 PageID #: 120

In Butterworth, the Supreme Court held that a witnesses who testified before

a Florida grand jury could not be prohibited from disclosing the substance of his

testimony after the term of the grand jury had ended. Butterworth, 410 U.S. at 626.

However, the Supreme Court did not permit the witness to discuss his experience

before the grand jury, and limited its holding to allow the witness to divulge

information of which he was in possession before he testified before the grand jury,

and not information which he may have obtained as a result of his participation in

the proceedings of the grand jury. Id. at 629 n.2, 631-32 (emphasis added).

In this case, unlike in Butterworth, Plaintiff proposes to divulge information

that he obtained as a direct result of his participation in the Wilson grand jury

proceedings. Such information, especially as it relates to evidence and witnesses, is

not Plaintiffs to disclose, and would pose a clear and present danger to the persons

whose identities remain unknown to the public. Mo. Rev. Stat. 610.100.3.

Moreover, the disclosure of such information would be contrary to Missouri law, and

would be counter to the states interest in promoting a freedom of disclosure before

future grand juries. See, e.g., Mannon, 295 S.W.2d at 162; Douglas Oil Co. of

California v. Petrol Stops Northwest, 441 U.S. 211, 222 (1979) (in considering the

effects of disclosure on grand jury proceedings, the courts must consider not only

the immediate effects upon a particular grand jury, but also the possible effect upon

the functioning of future grand juries); see also Seattle Times Co. v. Rhinehart, 467

U.S. 20, 36 (1984) (protective order entered by state court was not an impermissible

prior restraint on free speech); Butterworth, 494 U.S. at 636-37 (loosening grand

13

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 14 of 17 PageID #: 121

jury secrecy risks subject[ing] grand jurors to a degree of press attention and public

prominence that might in the long run deter citizens from fearless performance of

their grand jury service (Scalia, J., concurring)).

Given that Plaintiff cannot show that he has a right under the First

Amendment to divulge evidence and witnesses that have not already been disclosed

to the public, the Court should dismiss Plaintiffs claims in this case.

III.

The Court should abstain from exercising jurisdiction.

As argued above in Part I.A, Plaintiff lacks standing to assert his claims

against Defendant in this case. However, even if the Court had jurisdiction to hear

Plaintiffs claims, the Court should abstain from exercising its jurisdiction in order

to preserve traditional principles of equity, comity, and federalism. Beavers v.

Arkansas State Bd. of Dental Examiners, 151 F.3d 838, 840 (8th Cir. 1998) (quoting

Alleghany Corp. v. McCartney, 896 F.2d 1138, 1142 (8th Cir. 1990)).

An injunction is an extraordinary remedy. Winter v. Natural Res. Def.

Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 24 (2008). In this case, Plaintiff is requesting the Court to

issue an injunction that would threaten the continued health and sound functioning

of Missouris grand jury system. Given the important state issues raised in this

case, the Court should abstain from exercising its jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims.

Indeed, abstention is proper under Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971), because

the oath sworn by Plaintiff is ongoing, and is subject to the continuing jurisdiction

of the St. Louis County Circuit Court where Plaintiff received his charge. See Mo.

Rev. Stat. 540.080 & 540.330; Chem. Fireproofing Corp. v. Bronksa, 553 S.W.2d

14

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 15 of 17 PageID #: 122

710, 718 (Mo. App. 1977) (Contempt proceedings are sue generis and are triable

only by the court against whose authority the contempts are charged. (punctuation

and citations removed)); see also Norwood v. Dickey, 409 F.3d 901, 903-04 (8th Cir.

2005) (abstaining from deciding whether attorney could be required to maintain

silence on disciplinary matter).

Abstention is also proper under the Supreme Courts decision in Railroad

Commission v. Pullman Co., because the resolution of Plaintiffs First Amendment

claims depend upon whether the St. Louis County Circuit Court would hold

Plaintiff to his oath, and thus, such claims are dependent upon, or may be

materially altered by, the determination of an uncertain issue of state law.

Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528, 534 (1965) (citing R.R. Commn v. Pullman

Co., 312 U.S. 496 (1941)).

Where Younger abstention is otherwise appropriate, the district court must

generally dismiss the action, not stay it pending final resolution of the state court

proceedings. Geier v. Missouri Ethics Commn, 715 F.3d 674, 678 (8th Cir. 2013)

(quotations and citation omitted). Accordingly, and for the foregoing reasons, the

Court should abstain from exercising jurisdiction over Plaintiffs claims in this case,

and dismiss all of Plaintiffs claims.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, Defendant McCulloch respectfully

requests the Court grant his Motion to Dismiss, and any other relief the Court

deems fair and appropriate.

15

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 16 of 17 PageID #: 123

Respectfully submitted,

CHRIS KOSTER,

Attorney General

/s/ David Hansen

DAVID HANSEN

Assistant Attorney General

Missouri Bar No. 40990

Post Office Box 899

Jefferson City, MO 65102

Phone: (573) 751-9635

Fax: (573) 751-2096

David.Hansen@ago.mo.gov

PETER J. KRANE

St. Louis County Counselors Office

Missouri Bar No. 32546

41 South Central Avenue

Clayton, MO 63015

Phone: (314) 615-7042

PKrane@stlouisco.com

H. ANTHONY RELYS

Assistant Attorney General

Missouri Bar No. 63190

Assistant Attorney General

Post Office Box 861

St. Louis, MO 63188

Phone: (314) 340-7861

Fax: (314) 340-7029

Tony.Relys@ago.mo.gov

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT

ROBERT P. MCCULLOCH

16

Case: 4:15-cv-00006-RWS Doc. #: 28 Filed: 02/09/15 Page: 17 of 17 PageID #: 124

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on February 9, 2015, the foregoing Memorandum in

Support of Defendant Robert P. McCullochs Motion to Dismiss was filed

and served via the Courts electronic filing system upon all counsel of record.

/s/ David Hansen

David Hansen

Assistant Attorney General

You might also like

- Orlando Shooter Omar Mateen's AutopsyDocument17 pagesOrlando Shooter Omar Mateen's AutopsyJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Carlson ComplaintDocument8 pagesCarlson ComplaintMediaite100% (1)

- Read Remarks of FBI Director James ComeyDocument7 pagesRead Remarks of FBI Director James Comeykballuck1100% (2)

- Prince Search Warrant SealedDocument5 pagesPrince Search Warrant SealedJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Prince Invoice From City of Moline, Illinois For Emergency ResponseDocument1 pagePrince Invoice From City of Moline, Illinois For Emergency ResponseJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Unredacted Transcript of Call Between Omar Mateen and Orlando 911Document1 pageUnredacted Transcript of Call Between Omar Mateen and Orlando 911Jason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Orlando Nightclub Shooting TranscriptDocument3 pagesOrlando Nightclub Shooting TranscriptJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

- Prince Autopsy ReportDocument1 pagePrince Autopsy ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Omar Mateen Letter of RecommendationDocument1 pageOmar Mateen Letter of RecommendationJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Omar Mateen Criminal ChargeDocument1 pageOmar Mateen Criminal ChargeJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Omar Mateen Florida Security Guard RecordsDocument63 pagesOmar Mateen Florida Security Guard RecordsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Prince Documentation of DeathDocument1 pagePrince Documentation of DeathJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Jason Dalton's Interview With Kalamazoo PoliceDocument10 pagesJason Dalton's Interview With Kalamazoo PoliceJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Meechaiel Criner Arrest Warrant in UT Student HomicideDocument5 pagesMeechaiel Criner Arrest Warrant in UT Student HomicideJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Order Appointing Special Administrator in Prince Rogers Nelson EstateDocument2 pagesOrder Appointing Special Administrator in Prince Rogers Nelson EstateMinnesota Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Waco Police Response To Yahoo NewsDocument4 pagesWaco Police Response To Yahoo NewsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Moline, Illinois Fire Department Records On Prince Emergency LandingDocument8 pagesMoline, Illinois Fire Department Records On Prince Emergency LandingJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Understanding Firearms Assaults Against Police in The USDocument60 pagesUnderstanding Firearms Assaults Against Police in The USJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Dylann Roof Arrest Police Incident ReportDocument4 pagesDylann Roof Arrest Police Incident ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

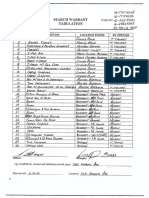

- Jason Dalton Police Search Warrant ReturnsDocument4 pagesJason Dalton Police Search Warrant ReturnsJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Ferguson Chief of Police Final Four CandidatesDocument2 pagesFerguson Chief of Police Final Four CandidatesJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- TSA Terms and Conditions For Trained CaninesDocument30 pagesTSA Terms and Conditions For Trained CaninesJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Suspected Kalamazoo Shooter Jason Dalton Criminal ComplaintDocument3 pagesSuspected Kalamazoo Shooter Jason Dalton Criminal ComplaintJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Judge's Evidence Ruling in Eric Casebolt Arrest of Albert BrownDocument4 pagesJudge's Evidence Ruling in Eric Casebolt Arrest of Albert BrownJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Jared Fogle Guilty Plea AgreementDocument27 pagesJared Fogle Guilty Plea AgreementJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- James Holmes NotebookDocument35 pagesJames Holmes NotebookJason Sickles, Yahoo News75% (4)

- Michael Brown Family Wrongful Death SuitDocument44 pagesMichael Brown Family Wrongful Death SuitJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- Waco, Texas Twin Peaks Arrest ReportDocument1 pageWaco, Texas Twin Peaks Arrest ReportJason Sickles, Yahoo News100% (1)

- State of Colorado v. James Holmes Jury QuestionnareDocument18 pagesState of Colorado v. James Holmes Jury QuestionnareJason Sickles, Yahoo NewsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- E2415 PDFDocument4 pagesE2415 PDFdannychacon27No ratings yet

- Teacher swap agreement for family reasonsDocument4 pagesTeacher swap agreement for family reasonsKimber LeeNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Development of High School LearnersDocument30 pagesCognitive Development of High School LearnersJelo BacaniNo ratings yet

- Rock Art and Metal TradeDocument22 pagesRock Art and Metal TradeKavu RI100% (1)

- 7 Q Ans Pip and The ConvictDocument3 pages7 Q Ans Pip and The ConvictRUTUJA KALE50% (2)

- Organizational CultureDocument76 pagesOrganizational Culturenaty fishNo ratings yet

- Surgical Orthodontics Library DissertationDocument5 pagesSurgical Orthodontics Library DissertationNAVEEN ROY100% (2)

- Annexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IDocument4 pagesAnnexure 2 Form 72 (Scope) Annexure IVaghasiyaBipinNo ratings yet

- GeM Bidding 2920423 - 2Document4 pagesGeM Bidding 2920423 - 2Sulvine CharlieNo ratings yet

- Individual Assessment Forms1Document9 pagesIndividual Assessment Forms1Maria Ivz ElborNo ratings yet

- (Section-A / Aip) : Delhi Public School GandhinagarDocument2 pages(Section-A / Aip) : Delhi Public School GandhinagarVvs SadanNo ratings yet

- Sewing Threads From Polyester Staple FibreDocument13 pagesSewing Threads From Polyester Staple FibreganeshaniitdNo ratings yet

- The Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerDocument33 pagesThe Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerBeto TNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Document17 pages10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Aubin DiffoNo ratings yet

- Solar Powered Rickshaw PDFDocument65 pagesSolar Powered Rickshaw PDFPrãvëèñ Hêgådë100% (1)

- 14 Worst Breakfast FoodsDocument31 pages14 Worst Breakfast Foodscora4eva5699100% (1)

- Timpuri Verbale Engleza RezumatDocument5 pagesTimpuri Verbale Engleza RezumatBogdan StefanNo ratings yet

- General Ethics: The Importance of EthicsDocument2 pagesGeneral Ethics: The Importance of EthicsLegendXNo ratings yet

- Oilwell Fishing Operations Tools and TechniquesDocument126 pagesOilwell Fishing Operations Tools and Techniqueskevin100% (2)

- Final Project Report On Potential of Vending MachinesDocument24 pagesFinal Project Report On Potential of Vending Machinessatnam_monu80% (5)

- Bell I Do Final PrintoutDocument38 pagesBell I Do Final PrintoutAthel BellidoNo ratings yet

- Total Product Marketing Procedures: A Case Study On "BSRM Xtreme 500W"Document75 pagesTotal Product Marketing Procedures: A Case Study On "BSRM Xtreme 500W"Yasir Alam100% (1)

- M8 UTS A. Sexual SelfDocument10 pagesM8 UTS A. Sexual SelfAnon UnoNo ratings yet

- Bondor MultiDocument8 pagesBondor MultiPria UtamaNo ratings yet

- Rev Transcription Style Guide v3.3Document18 pagesRev Transcription Style Guide v3.3jhjNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters vs Drilon Guidelines on Deployment BanDocument1 pagePhilippine Association of Service Exporters vs Drilon Guidelines on Deployment BanRhev Xandra AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Lab Report FormatDocument2 pagesLab Report Formatapi-276658659No ratings yet

- Jason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Document284 pagesJason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Abdalmonem Albaz100% (1)

- Scantype NNPC AdvertDocument3 pagesScantype NNPC AdvertAdeshola FunmilayoNo ratings yet

- FE 405 Ps 3 AnsDocument12 pagesFE 405 Ps 3 Anskannanv93No ratings yet