Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lepromatous Leprosy A Case Simulating Verrucous

Uploaded by

Hadi FirmansyahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lepromatous Leprosy A Case Simulating Verrucous

Uploaded by

Hadi FirmansyahCopyright:

Available Formats

Hong Kong J. Dermatol. Venereol.

(2012) 20, 77-81

Case Report

Lepromatous leprosy: a case simulating verrucous

carcinoma

MM Chang

and PCL Choi

A 59-year-old immigrant from China presented with a rapidly-enlarging exophytic growth on his

left heel for 4 months. He was also found to have peripheral neuropathy, Charcot's joint, diffuse

erythematous papules and acquired ichthyosis. Classical histologic features of leprosy were noted,

together with atypical verrucoid proliferation. The diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made

after clinical-pathological correlation and confirmation by polymerase chain reaction.

Keywords: Digitate papules, lepromatous leprosy, leprosy, multibacillary leprosy, verrucous

carcinoma

Introduction

The cutaneous manifestations of leprosy are vast.

We report a case of lepromatous leprosy with

Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine and

Therapeutics, Prince of W

ales Hospital, Hong Kong

Wales

MM Chang, MBChB, MRCP

Department of Anatomical and Cellular P

athology

Pathology

athology,,

Prince of W

ales Hospital, Hong Kong

Wales

PCL Choi, MBChB, FRCPA

Correspondence to: Dr. MM Chang

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, 9/F Clinical

Sciences Building, Prince of Wales Hospital, 30-32 Ngan

Shing Street, Shatin, New Territories

classical clinical and histological features, but also

co-existing with verrucoid growth, which is seldom

encountered.

Case report

A 59-year-old man was referred to the Orthopaedic

Tumour Clinic for a fungating growth on his left

heel for four months. It was asymptomatic but

growing rapidly. There was no history of trauma

or contact with fish. He had a history of closed

fracture on the same ankle that was treated

conservatively in childhood, and carcinoma of

rectum, now in remission, following surgery and

chemo-radiation therapy 12 years ago.

78

MM Chang and PCL Choi

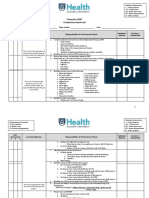

Clinically, the mass was 45 cm, with verrucous

surface and irregular border (Figure 1). There was

no satellite lesion or regional lymphadenopathy.

The provisional diagnosis by the orthopaedic team

was squamous cell carcinoma. MRI excluded deep

fascial invasion. Wide local excision followed by

staged skin graft was performed.

The patient was referred to the dermatology team

when the histology suggested otherwise. On

further enquiry, he complained of insidious onset

of dry skin, sensation loss of the extremities causing

frequent scald injuries after handling hot water

and progressive painless deformity of left ankle

from which he reported difficulty finding

appropriate shoes. Social history revealed that he

was born and immigrated from a village in

Guangdong 40 years ago, but he did not recall

any history of similar condition among his close

family members. On examination, he had slight

saddle-nose deformity, Charcot's joint on the left

ankle (Figure 2), acquired ichthyosis on the limbs,

multiple non-descript ill-defined erythematous

papules on the back (Figures 3 & 4) and enlarged

ulnar nerves on palpation. Peripheral neuropathy

was confirmed on nerve conduction study.

Histologically, there was verrucoid epidermal

hyperplasia without invasion, atypia or increased

mitotic activities (Figure 5). There were patchy

mixed inflammatory lymphohistiocytic infiltrates

and some plasma cells. Globi formation was

noted with foamy histiocytes (Figures 6 & 7). ZiehlNeelsen stain and Wade-Fite stains showed

abundant acid-fast bacilli (Figure 8), while PAS,

Grocott, Warthin-Starry and Gram stains were all

negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

of paraffin tissue was positive for Mycobacterium

leprae DNA but not M. tuberculosis. A second skin

Figure 1. Verrucous growth on heel.

Figure 2. Charcot's joint.

Figure 3. A close-up of digitate-like ill-defined

papules on back.

Lepromatous leprosy in a Chinese male

79

biopsy on a papule on the back also showed

identical histology (Figure 6).

The diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made

and the patient was started on rifampicin, dapsone

and minocycline in hospital. There was no

observable reaction on treatment and the graft

was taking well. Screening for HIV and diabetes

was negative. On discharge, he was referred to

the Leprosy Skin Clinic for continuation of multidrug therapy and contact tracing.

Figure 4. Multiple erythematous papules on back.

Figure 6. Biopsy from the back showed intradermal

collections of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Note the

presence of globi (H&E, Original magnification 20).

Figure 5. Low magnification showed verruoid

epidermal hyperplasia with underlying fibrous stroma

(H&E, Original magnification 20).

Figure 7. Medium magnification showed the presence

of globi admixed with lymphocytes and histiocytes

(H&E, Original magnification 200).

80

MM Chang and PCL Choi

Figure 8. Wade-Fite stain demonstrated many

intracellular acid fast bacilli (red in stain) (WF, Original

magnification 40).

Discussion

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infection of

the skin and peripheral nerves. It is transmitted

by Mycobacteria leprae (M. leprae), an obligate

intracellular Gram-positive bacillus with acid-fast

property and affinity for macrophages and

Schwann cells. It is a global disease affecting all

races, highly endemic in Africa and South

America, and prevalent in developing countries

in South-East Asia and parts of China. With the

introduction of WHO multi-drug therapy (MDT),

the disease is now controlled with decreasing

prevalence. In fact, Hong Kong is declared by

WHO to be eliminated from leprosy 1 with its

incidence of 0.088/10000 population. In the

1950s and 60s, the majority of leprosy patients

in Hong Kong (90%) were born in China,2 while

in recent years, imported leprosy from South East

Asian countries accounted for the majority.

The infection caused by M. leprae carries a long

incubation period, from months to 20 years,

averaging three to five years. The majority of

exposed individuals do not develop disease.

Host genetic and environmental factors influence

individual susceptibility to infection and

disease progression. In lepromatous leprosy, a

p r e d o m i n a n t-T h 2 r e s p o n s e s u p p r e s s e s

macrophage activity and cell mediated immunity

while a heightened Th1 response is found in

tuberculoid leprosy. Several leprosy susceptibility

loci on chromosome 6 and 10 are found; and

the presence of HLA allele DQ1 gears towards

lepromatous expression. In a genome-wide

association study in Han Chinese, novel

association with NOD2, TNFSF15, RIPK2 are

found, indicating heterogeneity of genetic

susceptibility between ethnic groups.3 Transmission

results from early childhood close contact with a

source with high infectivity (lepromatous leprosy),

and spreading by droplets of nasal or oral

secretions. The household risk of acquiring disease

in an endemic area is 10%. There are a few reports

of infections acquired through open wound and

fomites, and, recently, armadillos as a zoonotic

transmission. 4 Moreover, another species,

Mycobacterium lepromatosis, has been found to

cause diffuse form of lepromatous leprosy in

Mexico and the Caribbean.5

Our patient had classical clinical and histologic

features of lepromatous leprosy, which

represented the more severe spectrum of disease

with multi-bacillary involvement and poor host

immunity. What was atypical would be the late

age of onset, very long incubation and verrucoid

presentation. Most literature reported special

forms of leprosy as histoid, dermatofibroma-like

papules, digitate or shagreen-like patches.

Verrucoid presentations are rare in leprosy

and were found in few anecdotal reports

of lepromatous leprosy with coexistent

chromoblastomycosis, 6 or in HIV-positive

individuals.7 A more logical association would be

squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic

unhealed leg ulcers, and even with that, verrucous

carcinoma arising from such lesion was rarely

reported. 8 The underlying reason that our

immunocompetent patient developed verrucoid

growth was obscure. Without other supporting

cutaneous suggestions of leprosy, the differential

diagnosis would have been malignant tumours

(squamous cell carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma,

Lepromatous leprosy in a Chinese male

cutaneous metastasis, amelanotic melanoma), or

infection (giant condyloma, deep fungal infection,

atypical mycobacterial infection or tuberculosis

verrucosa cutis). A biopsy for histology and culture

would be helpful to establish the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of leprosy is suggested by (1) the

presence of skin lesions with definite sensory loss

(except borderline lepromatous or lepromatous

leprosy), (2) thickened peripheral nerves, or (3)

the presence of acid-fast bacilli on skin smears or

tissue biopsy. 9 The sensitivity and positive

predictive values based on the above diagnostic

features are more than 95% in endemic countries.10

M. leprae cannot be cultured in artificial media.

Newer techniques like serology for M. leprae

antibody, phenolic glycolipid-1 (PGL-1), or PCR

for M. leprae DNA detection are useful in

multibacillary disease with high bacterial load. The

sensitivity for serology ranges from 40%

(paucibacillary) to 90% (multibacillary) and it can

be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment

as its level declines with MDT. The sensitivity of

PCR using M. leprae specific repetitive sequence

in multibacillary disease is 80% and can be

performed on skin or nasal biopsy specimen and

extracts of slit skin smear.11 These tests are used

more as identification tools rather than detection

tools for leprosy, as the sensitivity for paucibacillary

disease is low overall.

Standard multi-drug therapy with monthly

supervised rifampicin 600 mg and clofazimine

300 mg, and daily self-administered dapsone

100 mg and clofazimine 100 mg was prescribed

to our patient. He tolerated treatment well with

counseling, psychological support and regular

follow-up. Podiatry assessment and footwear

adjustment was made. The relapse rate after two

years of WHO-MDT is quoted to be 0.77%

globally1 to 3% locally.12 In our locality, a more

conservative approach is adopted with prolonged

MDT until all skin lesions are inactive, followed

by dapsone monotherapy for 10 years after the

slit skin smear is negative.

81

In conclusion, although leprosy is a fading disease,

clinicians should remain vigilant in the screening

and diagnosis of leprosy in Hong Kong. Early

specialist referral is recommended in view of

its protean manifestations and infectious

implications.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Lo Kuen Kong

and Dr Luk Nai Ming, for their supervision, and

Dr Tse Lung Fung, for supplying the surgical

photo.

References

1.

2.

World health organization leprosy fact sheet.

Ho CK. Leprosy - a review. Hong Kong J Dermatol

Venereol 1999;7:65-70.

3. Zhang FR, Huang W, Chen SM, Sun LD, Liu H, Li Y, et

al. Genome wide association study of leprosy. N Engl J

Med 2009; 361: 2609-18.

4. Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, Busso P, Rougemont J,

Paniz-Mondolfi A, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in

the Southern United States. N Engl J Med 2011;364:

1626-33.

5. Han XY, Sizer KC, Thompson EJ, Kabanja J, Li J, Hu P,

et al. Comparative sequence analysis of Mycobacterium

leprae and the new leprosy-causing Mycobacterium

lepromatosis. J Bacteriol 2009;191:6067-74.

6. Silva Cde M, Silva AC, Marques SC, Saldanha AC,

Nascimento JD, Branco MR, et al. Chromoblastosis

associated with leprosy: report of 2 cases. Rev Soc Bras

Med Trop 1994;27:241-4.

7. Manjare AK, Tambe SA, Phiske MM, Jerajani HR. Atypical

presentation of leprosy in HIV. Indian J Lepr. 2010;82:

85-9.

8. Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Squamous cell carcinoma

in plantar ulcers in leprosy: a study of 11 cases. Indian

J Lepr 2003;75:219-24.

9. Walker SL, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Clin Dermatol 2007;

25:165-72.

10. Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet 2004;363:

1209-19.

11. Kang TJ, Kim SK, Lee SB, Chae GT, Kim JP. Comparison

of 2 different amplification products in the diagnosis of

Mycobacterium leprae. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28:

420-4.

12. Ho CK, Lo KK. Epidemiology of leprosy and response

to treatment in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2006;

12:174-9.

You might also like

- Lower Blepharoplasty: How To Avoid Complications: Dr. Vincent KH KWANDocument3 pagesLower Blepharoplasty: How To Avoid Complications: Dr. Vincent KH KWANHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Medical Journals Year in Body Mods 2012 12-30-12Document24 pagesMedical Journals Year in Body Mods 2012 12-30-12Hadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Medical Journals Year in Body Mods 2012 12-30-12Document24 pagesMedical Journals Year in Body Mods 2012 12-30-12Hadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Fatal Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Evolving From A Localized Verrucous Epidermal NevusDocument11 pagesFatal Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Evolving From A Localized Verrucous Epidermal NevusHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Co-Isolation of Trichosporon Inkin and CandidaDocument8 pagesCo-Isolation of Trichosporon Inkin and CandidaHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Chae Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyDocument7 pagesChae Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 10 5923 J Surgery 20140301 03 PDFDocument4 pages10 5923 J Surgery 20140301 03 PDFJacobMsangNo ratings yet

- Bleomycin and The SkinDocument8 pagesBleomycin and The SkinHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic ScarsDocument9 pagesTreatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic ScarsHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Bleomycin in The Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars by Multiple Needle PuncturesDocument10 pagesBleomycin in The Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars by Multiple Needle PuncturesHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- White Piedra in A Mother and DaughterDocument3 pagesWhite Piedra in A Mother and DaughterHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- A Case of Basal Cell Carcinoma Arising in Epidermal Nevus: CameoDocument3 pagesA Case of Basal Cell Carcinoma Arising in Epidermal Nevus: CameoHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Xerosis CutisDocument6 pagesXerosis CutisHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument3 pagesDocumentHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Wilske B. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis 2005Document12 pagesWilske B. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis 2005Hadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Thayer Martin Agar Procedure 08Document1 pageThayer Martin Agar Procedure 08Hadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Verrucous Lepromatous Leprosy A Rare Form ofDocument4 pagesVerrucous Lepromatous Leprosy A Rare Form ofHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Collodion Baby and Loricrin Keratoderma: A Case Report and Mutation AnalysisDocument5 pagesCollodion Baby and Loricrin Keratoderma: A Case Report and Mutation AnalysisHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- JorgenDocument5 pagesJorgenHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Cutaneous Annular Sarcoidosis Developing On A Background of Exogenous Ochronosis: A Report of Two Cases and Review of The LiteratureDocument5 pagesCutaneous Annular Sarcoidosis Developing On A Background of Exogenous Ochronosis: A Report of Two Cases and Review of The LiteratureHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Dermatologica Sinica: Cheng-Han Lee, Yi-Chun Chen, Yung-Tsu Cho, Chia-Ying Chang, Chia-Yu ChuDocument5 pagesDermatologica Sinica: Cheng-Han Lee, Yi-Chun Chen, Yung-Tsu Cho, Chia-Ying Chang, Chia-Yu ChuHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 1999 1 1 29 36Document8 pages1999 1 1 29 36Hadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- New Developments in Ochronosis: Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesNew Developments in Ochronosis: Review of The LiteratureHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 1486 - Vitamin D PaperDocument9 pages1486 - Vitamin D PaperHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- JorgenDocument5 pagesJorgenHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- New Developments in Ochronosis: Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesNew Developments in Ochronosis: Review of The LiteratureHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Xerosis CutisDocument6 pagesXerosis CutisHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Patch Test FDEDocument8 pagesPatch Test FDEHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Can P Rio Biotics Prevent VaginitisDocument2 pagesCan P Rio Biotics Prevent VaginitisHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Informed Consent TimetableDocument11 pagesInformed Consent TimetableAkita C.No ratings yet

- Med school memes that are medically funnyDocument1 pageMed school memes that are medically funnylostinparadise0331No ratings yet

- Eosinophin in Infectious DiseaseDocument29 pagesEosinophin in Infectious DiseasentnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Caseheet PDFDocument23 pagesPediatric Caseheet PDFAparna DeviNo ratings yet

- Observational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant InteractionDocument34 pagesObservational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant Interactionqs-30No ratings yet

- MSA Testing Reveals Body's Energetic HealthDocument4 pagesMSA Testing Reveals Body's Energetic HealthDenise MathreNo ratings yet

- The MAST Test: A Simple Screening Tool for Alcohol ProblemsDocument3 pagesThe MAST Test: A Simple Screening Tool for Alcohol Problemsmysteryvan1981No ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Salts - A Formulation Trick or A Clinical Conundrum - The British Journal of Cardiology PDFDocument9 pagesPharmaceutical Salts - A Formulation Trick or A Clinical Conundrum - The British Journal of Cardiology PDFNájla KassabNo ratings yet

- NTR OductionDocument83 pagesNTR OductionmalathiNo ratings yet

- Blessing IwezueDocument3 pagesBlessing Iwezueanon-792990100% (2)

- Xtampza Vs Oxycontin - Main Differences and SimilaritiesDocument4 pagesXtampza Vs Oxycontin - Main Differences and SimilaritiesNicholas FeatherstonNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines For Treating Caries in Adults Following A Minimal Intervention Policy-Evidence and Consensus Based Report PDFDocument11 pagesClinical Guidelines For Treating Caries in Adults Following A Minimal Intervention Policy-Evidence and Consensus Based Report PDFFabian ArangoNo ratings yet

- Reversal of Fortune: The True Story of Claus von Bülow's Conviction and Alan Dershowitz's Innovative DefenseDocument9 pagesReversal of Fortune: The True Story of Claus von Bülow's Conviction and Alan Dershowitz's Innovative Defensetamakiusui18No ratings yet

- 2021-2022 Sem 2 Lecture 2 Basic Tests in Vision Screenings - Student VersionDocument123 pages2021-2022 Sem 2 Lecture 2 Basic Tests in Vision Screenings - Student Versionpi55aNo ratings yet

- MSDS Berkat Saintifindo PDFDocument27 pagesMSDS Berkat Saintifindo PDFDianSelviaNo ratings yet

- CIPHIDocument256 pagesCIPHIसदानंद देशपांडेNo ratings yet

- Review Article On History of LM Potency - Tracing Its Roots in The PastDocument6 pagesReview Article On History of LM Potency - Tracing Its Roots in The PastRenu BalaNo ratings yet

- 2 Months To LiveDocument26 pages2 Months To LivedtsimonaNo ratings yet

- PMLSP 2 ReviewerDocument38 pagesPMLSP 2 ReviewerSophia Mae ClavecillaNo ratings yet

- Swami Paramarthananda's Talks on Self-KnowledgeDocument332 pagesSwami Paramarthananda's Talks on Self-Knowledgemuralipmd100% (1)

- Fluconazole Final Dossier - Enrollemt Number 2Document139 pagesFluconazole Final Dossier - Enrollemt Number 2lathasunil1976No ratings yet

- Bioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookDocument228 pagesBioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- Prismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFDocument5 pagesPrismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFalex100% (1)

- Work Sheet, Lesson 5Document7 pagesWork Sheet, Lesson 5WasimHassanShahNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument10 pagesCardiovascular SystemitsmesuvekshaNo ratings yet

- Anatomic Therapy English PDFDocument339 pagesAnatomic Therapy English PDFBabou Parassouraman100% (3)

- 01 - Chance - Fletcher, Clinical Epidemiology The Essentials, 5th EditionDocument19 pages01 - Chance - Fletcher, Clinical Epidemiology The Essentials, 5th EditionDaniel PalmaNo ratings yet

- Ha Ema To PoiesisDocument38 pagesHa Ema To PoiesisEmma Joel OtaiNo ratings yet

- The Herbal Market of Thessaloniki N GreeDocument19 pagesThe Herbal Market of Thessaloniki N GreeDanaNo ratings yet

- 2) Megaloblastic AnemiaDocument17 pages2) Megaloblastic AnemiaAndrea Aprilia100% (1)