Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diaz Et Al (2001) - Cognition, Anxiety, and Prediction of Performance

Uploaded by

Lanz OlivesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Diaz Et Al (2001) - Cognition, Anxiety, and Prediction of Performance

Uploaded by

Lanz OlivesCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Educational Psycholog\

2001. Vol. 93, No. 2, 420-429

Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.

0O22-0663/01/S5.0O DOI: 10.1037//0022-0663.93.2.420

Cognition, Anxiety, and Prediction of Performance

in 1st-Year Law Students

Rolando J. Diaz, Carol R. Glass, Diane B. Arnkoff, and Marian Tanofsky-Kraff

The Catholic University of America

Two models to predict academic performance using ability, affective, and cognitive variables were

evaluated using students in their 1st year of law school. Participants were assessed before the beginning

of classes and prior to and immediately following 2 anxiety-arousing lst-year academic milestones: a

final exam and an oral argument. In the path analysis for the exam model, only the Law School Aptitude

Test was predictive of performance. Trait anxiety predicted self-efficacy for cognitive control, which

predicted thoughts, which in turn predicted state anxiety. State anxiety, however, did not predict exam

grades. In the oral argument model, a clear path of significant predictors could be traced from

communication apprehension to self-efficacy for affective control, to state anxiety, and finally to oral

argument score. Thus, different processes appear to operate in each of the 2 academic tasks. The

implications of the results for law school education and future research are discussed.

Law school has long been documented as a stressful experience,

with the first year being especially problematic (e.g., Mclntosh,

Key well, Reifman, & Ellsworth, 1994; Schick, 1996). Many law

students suffer from elevated levels of anxiety and depression

(Dammeyer & Nunez, 1999; Shanfield & Benjamin, 1985). The

origins of such psychological distress appear to be a number of

sources in the law school learning environment, including threats

to self-esteem from the competitive atmosphere, class ranking,

overwhelming workload, intimidating Socratic teaching methods,

and single end-of-semester exams with little prior performance

feedback (Carney, 1990). Although it has been suggested that

academic success in law school may be related to student personality (Boyle & Dunn, 1998), the extent to which anxiety and stress

impact law school performance has remained largely unexamined.

have focused on the importance of negative cognition in the form

of self-deprecatory thoughts and low self-efficacy (Beck & Emery,

1985). Further, models that suggest paths of influence may more

thoroughly explain performance than would the examination of

individual variables in relation to outcome (Ozer & Bandura,

1990). For example, in a study of performance on doctoral dissertation oral exams, Arnkoff, Glass, and Robinson (1992) proposed

a model that incorporated cognitive and affective variables into a

sequential path. Results demonstrated the importance of thoughts

and self-efficacy in the prediction of anxiety. Self-efficacy for

cognitive control was predictive of students' thoughts prior to and

during their doctoral oral examinations. The fact that neither

thoughts nor anxiety predicted student performance is likely due to

the restricted range of performance scores, as all students passed

the exam, and 90% scored at or above the midpoint of the rating

scale.

A further study used a path model to predict oral examination

performance in soldiers being evaluated by a military board, where

performance outcome was based both on soldiers' ability to answer questions and on their military bearing and composure (Glass

et al., 1995). Dispositional anxiety was found to predict preexamination anxiety but not self-efficacy for performance. Preexamination anxiety predicted negative thoughts, which in turn predicted

performance independently of the anxiety experienced during the

evaluation.

Although path models have proven informative in a variety of

contexts, no study to date has used such models to investigate

predictors of law school performance. Researchers have also

tended not to look at predictors of outcome on varying tasks in one

population. In the law school setting, an understanding of predictors of success in different tasks could have important implications

for law school educators and for counselors working with law

students.

Models of Performance

Drawing on both previous research and anxiety theory, the

present study aimed to develop and test two models of first-year

law school performance. Recent conceptualizations of anxiety

Rolando J. Diaz, Carol R. Glass, Diane B. Arnkoff, and Marian

Tanofsky-Kraff, Department of Psychology, The Catholic University of

America.

This study was conducted as part of Rolando J. Diaz's doctoral dissertation at The Catholic University of America, under the direction of Carol

R. Glass and Diane B. Arnkoff.

We thank the students at the Columbus School of Law for their willingness to participate. We are also grateful to those who facilitated this

study, including Leah Wortham (then Associate Dean for External and

Student Affairs), John F. Lord (then Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs),

Doris Malig, and Michael Koby. Special thanks go to Ronnie Siddique and

Katie Cimbolic for their assistance in data collection and entry.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Carol R.

Glass, Department of Psychology, The Catholic University of America,

Washington, District of Columbia 20064. Electronic mail may be sent to

glass@cua.edu.

Models of Examination and Oral Argument Performance

In this study, we chose to investigate two distinct yet stressful

first-year law school academic milestones: the final examination in

420

PREDICTION OF LAW STUDENT PERFORMANCE

students' first-semester course on contracts, and a second-semester

oral argument of a case in front of a panel of judges. Final

examinations in law school are highly stressful in that they typically determine the entire grade for a course, often involve the

novel experience of having to present answers in written form (as

opposed to the verbal form used in class), and pose questions often

different from those asked in class (Kissam, 1989). The oral

argument often fosters competitiveness in students (Auerbach,

1984) and can be intimidating due to the prospect of having to

speak in public in an evaluative setting. The ability to perform at

a high level on both types of tasks has important academic and

career implications. Two models were thus proposed, in which we

hypothesized that performance on examinations and oral argument

is a function of a series of variables organized into three phases: (a)

an antecedent phase, (b) a preperformance phase, and (c) a performance phase. Performance outcome was measured by examination grades and by judges' ratings of oral argument performance.

Antecedent Phase

Antecedent phase constructs consisted of dispositional anxiety

variables and ability variables, both of which were theorized to

play a role in the development of self-efficacy and ultimately to

affect actual task performance. Trait anxiety (a personality characteristic associated with a relatively high level of chronic anxiety

and a likelihood of experiencing anxiety easily), test anxiety, and

anxiety in public speaking situations have been shown to correlate

with undergraduate performance (e.g., Hunsley, 1985; Seipp,

1991). These three constructs were thus expected to play a similar

role in law students' responses to their final examination and oral

argument tasks. In addition, we included measures of academic

ability (undergraduate grade point average [GPA] and standardized test scores on the Law School Aptitude Test [LSAT]), which

have been found to be directly predictive of law school academic

performance (Linn & Hastings, 1984; Powers, 1982).

Preperformance Phase

In the second phase, preperformance factors consisted of three

aspects of self-efficacy expectations. Self-efficacy expectations are

cognitive convictions that individuals have regarding whether they

can carry out specific behaviors to achieve a desired outcome. A

number of elements, including prior accomplishments and emotional arousal, affect the development and maintenance of selfefficacy expectations (Bandura, 1977). Social cognitive theory

also postulates that perceived self-efficacy operates as a cognitive

mediator of anxiety arousal and action (Bandura, 1988). Selfefficacy beliefs have therefore been included, along with anxiety

and negative thoughts, in previous path models of behavior and

performance (e.g., Arnkoff et al., 1992; Ozer & Bandura, 1990). A

relationship between self-efficacy for performance and academic

achievement has been found (Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991;

Smith, Arnkoff, & Wright, 1990). In addition, self-efficacy for

grade attainment on a test was shown to be related to anxiety level

on that test (Zohar, 1998).

Research on self-efficacy has also revealed that individuals who

believe they can control their affect and negative cognitions may

be able to cope better with anxiety and may be less likely to

experience intrusive negative thoughts (Arch, 1992; Bandura,

421

1988). These three aspects of self-efficacy were thus assessed in

the present study: self-efficacy for successful performance, selfefficacy for affective control (over subjective anxiety), and selfefficacy for cognitive control (of intrusive, negative thoughts). We

posited that antecedent-phase predispositional constructs would

influence self-efficacy expectations during the preperformance

phase, which in turn would affect performance-phase variables.

Performance Phase

Finally, performance-related constructs, such as the thoughts

and state anxiety experienced during the exam and oral argument,

were expected to have an effect on actual performance. An individual's thoughts have been theorized to either facilitate coping or

interfere with goal behavior (e.g., Arnkoff et al., 1992; Covington

& Omelich, 1990).

Research on examinations has found that cognition is related to

both test anxiety and performance, with negative thoughts correlating positively with test anxiety (Galassi, Frierson, & Sharer,

1981; Kent & Jambunathan, 1989) and negative thoughts, test

anxiety, and worry inversely relating to academic performance

(Bruch, 1981; Deffenbacher, 1986). However, studies have found

that the state of mind (SOM) ratio of positive thoughts to positiveplus-negative thoughts (Schwartz & Garamoni, 1989) may be

more relevant to predicting anxiety and academic performance

than are negative thoughts alone (e.g., Arnkoff et al., 1992;

Schwartz & Garamoni, 1989). Therefore, we elected to use the

SOM ratio as the performance-phase cognitive variable for the

exam model in the present study.

Although no prior studies have investigated thoughts and selfefficacy in the context of oral argument, research has found that

anxious individuals generally have more negative thoughts in

speech settings than do less anxious people (Beidel, Turner, &

Dancu, 1985; Stopa & Clark, 1993). Further, Glass et al. (1995)

found that negative thoughts, but not the SOM ratio, predicted

performance on a career-related oral exam. We thus chose to use

the construct of negative thoughts as the cognitive variable in the

performance phase of the oral argument model.

In addition to thoughts, state anxiety may be an important

predictor of success during the performance phase. State anxiety is

experienced during a specified period of time and is assumed to

vary in intensity as a function of perceived threat (Spielberger &

Rickman, 1990). State anxiety in evaluation situations has been

examined often. For example, McCleary and Zucker (1991) found

anxiety levels in law students to be significantly higher than

undergraduate norms. There are also studies demonstrating that

state anxiety inversely predicts exam performance (Frierson &

Hoban, 1987; Hunsley, 1985). However, state anxiety was not

related to performance in path models that also included selfefficacy and negative thoughts (Arnkoff et al., 1992; Ozer &

Bandura, 1990).

In summary, the present study sought to predict the performance

of first-year law students on a first-semester final exam and on a

second-semester oral argument using path-analytic models. The

two models incorporated a range of predictor variables, including

dispositional anxiety, academic ability/aptitude, self-efficacy expectations, state anxiety, and negative thoughts. Correlates of law

school performance, including first-year class ranking in addition

422

DIAZ, GLASS, ARNKOFF, AND TANOFSKY-KRAFF

to exam grades and judges' oral argument ratings, were also

calculated.

Method

Participants

Participants were 184 first-year law students (91 men and 93 women,

representing 77% of the class) recruited during orientation sessions prior to

their first semester at a private, mid-Atlantic law school. Participants

ranged in age from 21 to 47 years (M = 24.04); 94% of the sample was less

than 30 years of age. The majority of the students were unmarried (n

157), and the remainder identified themselves as married or living as

married. Participants were primarily White/Caucasian (n = 154), with the

remainder being from various ethnic and racial backgrounds, including

African American (n = 11), Asian (n = 9), and Hispanic (n = 6). All

participants had taken the LSAT prior to applying to law school. Their

mean LSAT score of 154.84 (SD = 4.36) was significantly higher than the

national mean of 150. Zv = 6.51, p < .01. Participants' mean undergraduate GPA was 3.10 (SD = .36) and ranged from 1.98 to 3.81.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire included

questions assessing age, sex, education, race and ethnicity, marital status,

religious preference, and areas of potential legal specialization.

LSAT. The LSAT is a standardized aptitude test required for admission

to most U.S. law schools, and it assesses comprehension and analytical and

logical reasoning. A combined variable of LSAT score and undergraduate

GPA correlates highly with first-year law school GPA (Law School Admissions Council [LSAC], 1996).

Slate-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STA1). The STAI (Spielberger, Gorsuch,

Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs. 1983) was designed to assess both trait and state

anxiety, and it consists of two 20-item forms. The STAI-Trait asks participants to rate, on 4-point scales, how often they generally experience

certain feelings (e.g., "I am inclined to take things hard"). The STAI-State

form uses similar 4-point scales, on which participants rate how they feel

"right now" (e.g.. "1 feel nervous"). Both forms have been used extensively

in anxiety research and show good concurrent validity with other anxiety

measures. The STAI-Trait has strong test-retest reliability, whereas the

STAI-State has demonstrated low test-retest reliability, consistent with the

expected variability in state anxiety over time (Spielberger et al., 1983).

Reactions To Tests (RTT). The RTT (Sarason, 1982, 1984) is a 40-item

self-report measure of dispositional test anxiety. Four-point rating scales

are used to rate the extent to which each item is typical of one's own

reaction to tests (e.g., "I feel distressed and uneasy before tests"). The RTT

has shown moderate but significant concurrent validity with other test

anxiety measures, as well as an inverse relationship with academic performance (Sarason. 1984).

Personal Report of Communication Apprehension-24 (PRCA-24). The

PRCA-24 is a measure of apprehension or anxiety while speaking in public

situations. The most recent revision (the PRCA-24; McCroskey, 1993)

consists of 24 items on 5-point scales assessing communication apprehension in four areas; dyads, groups, meetings, and public speaking. The

PRCA-24 has demonstrated high internal consistency (McCroskey, 1984;

McCroskey, Beatty, Kearney, & Plax, 1985) and convergent validity with

the STAI-Trait form (Beatty, 1986).

Self-Efficacy Scales (SES). Two parallel 24-item questionnaires were

developed for this study to assess self-efficacy on the final exam (SESEX)

and on the oral argument (SES-OA), consistent with Bandura's (1986)

recommendation that self-efficacy expectations be assessed at the most

specific level possible. Both scales consisted of three eight-item subscales

designed to assess specific self-efficacy expectations: Cognitive ("I will be

able to stop myself from having thoughts unrelated to the contracts final

exam," "I will be able to concentrate only on the argument I'll be making"), Affective ("I will be able to control my nervousness when I take my

contracts final exam," "I will be able to relax during my moot court

argument"), and Performance ("I will do well on my contracts final exam,"

"1 will be able to argue the case I am given successfully"). Internal

consistency of each scale using Cronbach's alpha was .96.

Checklist of Positive and Negative Thoughts (CPNT). The CPNT (Galassi et al., 1981) was designed to assess thoughts during examinations

(e.g., "I won't have enough time to finish this test"). It has separate

subscales for positive and negative thoughts, which allow the calculation of

the SOM ratio (Schwartz & Garamoni, 1989). The original checklist format

was revised to assess how often students had each of these thoughts, using

a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). In addition, one item was dropped

because it was not relevant to the law school setting. Brown and Nelson

(1983), using a similar modification of the CPNT to assess thought frequency, found strong internal consistency coefficients for both positive and

negative thoughts. Galassi et al. (1981) found that highly test-anxious

individuals reported significantly higher numbers of negative and fewer

positive thoughts compared with controls.

Social Interaction Self-Statement TestPublic Speaking (S1SST-PS).

The SISST-PS is a revision of the original SISST, a measure of thoughts

in social interactions (Glass, Merluzzi, Biever, & Larsen, 1982). The

SISST-PS has two similar 15-item positive and negative thought subscales,

and it uses a response format from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). To modify

the SISST for a public speaking situation, items were rewritten to use

pronouns appropriate to this group context (e.g., "I'm really afraid of what

they'll think of me"), as had been done in an earlier revision (Turner &

Beidel, 1985). In addition, three positive items from the original SISST that

were not relevant to public speaking were replaced by three items from the

Scale of Thoughts in Oral Examinations (Arnkoff et al., 1992). Various

researchers have reported strong validity coefficients for the SISST (see

reviews by Glass & Arnkoff, 1994, 1997) and for its use in public speaking

situations (e.g., Beidel, Turner, Jacob, & Cooley, 1989).

Performance. The first-semester final exam grade for the contracts

course and the mean oral argument rating across judges served as the

primary measures of performance in the path analyses. Although students

had exams in three of their four fall courses, two of these courses were

taken by some students in the fall and some in the spring. The contracts

class was the only class with an exam taken simultaneously by all first-year

students in the fall semester. The exam was graded on a scale from 1 to 100

points. For the oral argument, attorneys and judges from the community

volunteered to serve as judges for the competition. Participants received an

overall performance rating from each member of the panel of three judges

who heard their argument, with 30 panels each hearing the arguments of

eight students. An average performance rating across judges was calculated

for each student. In addition, the judges rated students' level of observable

anxiety from 0 (not at all anxious) to 10 (extremely anxious). Finally, the

class ranking of students at the end of their first year, the key measure of

achievement used by the law school, served in correlational analyses as a

measure of overall academic performance.

Procedure

The study was conducted across five assessment points over the course

of the students' first year, and different numbers of participants were

present each time.1 At the law school orientation, prior to the beginning of

classes, 184 students volunteered to participate. They signed an informed-

Analyses were conducted to examine whether patterns of missing data

might have influenced the results. Students from the initial sample who

continued to participate at one or more of the four subsequent phases of the

study did not differ from those who chose not to participate on measures of

background ability (i.e., LSAT score and undergraduate GPA) and law

423

PREDICTION OF LAW STUDENT PERFORMANCE

consent form and a release-of-information form, allowing the investigators

access to their LSAT scores, undergraduate GPAs, contracts exam grade,

oral argument performance ratings, and first-year ranking. Participants then

completed the demographic questionnaire and a booklet that contained the

STAI-Trait, PRCA-24, and RTT (in counterbalanced order), in order to

assess trait anxiety, communication apprehension, and test anxiety,

respectively.

Four weeks prior to their first semester final exams, participants (n =

130) completed the SES-EX, which measured their self-efficacy for the

final exam. Immediately following their contracts exam, the CPNT and

STAI-State measures were administered to participants (n = 120) to assess

thoughts and state anxiety.

During their second semester of law school, participants (n = 67)

completed the SES-OA approximately 4 weeks prior to participating in an

oral argument, assessing their self-efficacy for this task. The oral argument

was a cocurricular appellate argument required of all first-year students.

Students prepared legal briefs for both the prosecution and the defense for

one of three assigned hypothetical cases. They then argued only one side

of their assigned case against a fellow student assigned to the other side.

The participants' performance did not have an impact on their course

grades, but they received specific feedback from the judges. Immediately

following the completion of the oral argument, participants (n = 87)

completed the SISST-PS and the STAI-State to measure their thoughts

and state anxiety during the argument.

Results

Correlates of Performance

Pearson correlations revealed that the only significant correlate

of exam grade was the antecedent aptitude variable of LSAT score

(see Table 1). Surprisingly, undergraduate GPA and test and trait

anxiety were not related to exam scores, nor were self-efficacy for

the exam, state anxiety, or thought variables.

For the oral argument, none of the antecedent variables (such as

LSAT, trait anxiety, or communication apprehension) were significantly correlated with performance, but the higher the preperformance level of self-efficacy for the exam, the significantly better

the oral argument scores. Self-efficacy for the oral argument was

related to performance to a similar degree, but it was not significant due to the much smaller number of participants who completed this measure. At the performance phase, the lower the

self-reported state anxiety and the anxiety observed by the judges,

the higher the oral argument performance score. Interestingly,

positive thoughts were significantly associated with oral argument

performance, but negative thoughts were not.

Finally, first-year class rank, a key outcome measure, was most

strongly related to antecedent variables. Specifically, both LSAT

and undergraduate GPA were predictive of class rank, and men

had better academic performance than did women in the first year

of law school. In addition, the greater the self-efficacy for the

contracts exam, the higher the class rank.

school performance (i.e., contracts exam grade, oral argument quality,

first-year law school class rank). However, those who chose to participate

prior to the final exam were significantly less trait and test anxious, and

those who completed measures after the oral argument had significantly

less test anxiety and communication apprehension, compared with those

who had declined to volunteer at those times.

Table 1

Correlates of Contracts Exam Grade, Oral Argument Score, and

Final Class Ranking

Outcome measure

Predictor

Demographic and ability variables

Sexb

Age

LSAT

Undergraduate GPA

Antecedent Phase Dispositional Anxiety

STAI-Trait

PRCA-24 (communication

apprehension)

RTT (test anxiety)

Preperformance phase

SES-EX

SES-OA

STAI-State (before exam)

STAI-State (before oral argument)

Performance phase

STAI-State (after exam)

STAIState (after oral argument)

CPNT-Positive Scale

CPNT-Negative Scale

SISST-PS (Positive thoughts)

SISST-PS (Negative thoughts)

Observed anxiety during oral

argument

Exam

grade

Oral

argument

Class

rank8

.13

.12

.34**

-.05

-.04

.00

-.10

.09

-.29**

.00

-.36***

-.18*

-.01

-.11

-.01

-.12

-.04

.03

-.15

.11

.06

.10

-.10

-.03

-.10

.21*

.21

.02

-.10

-.19*

.05

.01

-.04

-.16

-.04

-.02

-.16

-.10

.00

-.11

-.28**

.14

-.01

.33**

-.12

.07

-.05

-.09

.04

.20

.01

-.04

-.41***

-.02

Note, LSAT = Law School Aptitude Test; GPA = grade-point average;

STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; PRCA-24 = Personal Report of

Communication Apprehension-24; RTT = Reactions to Tests scale;

SES = Self-Efficacy Scale (EX = exam, OA = oral argument); CPNT =

Checklist of Positive and Negative Thoughts; SISST-PS = Social Interaction Self-Statement TestPublic Speaking.

a

The student at the top of the class was ranked 1. Thus, lower numbers

represent better performance (higher rank). b 0 = female, 1 = male.

*p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

Intercorrelations Among Predictor Variables

In contrast to the relatively few significant correlations between

predictor and outcome measures, there were numerous significant

intercorrelations among predictor variables (see Table 2). Dispositional anxiety scales (trait anxiety, test anxiety, and communication apprehension) were all significantly correlated with each other

and with negative thoughts and state anxiety, and they were

inversely related to self-efficacy. All three subscales of selfefficacy for the exam were significantly and inversely associated

with both state anxiety and negative thoughts during the exam

(which were highly correlated with each other). The three oralargument self-efficacy subscales were significantly inversely related to state anxiety, and self-efficacy for oral argument performance was significantly inversely correlated with negative

thoughts on that task. Again, state anxiety and negative thoughts

were strongly related. However, LSAT scores did not correlate

significantly with any of the other predictor variables.

Tests of the Causal Models

A recursive (unidirectional) path-analysis model with ordinary

least squares for the regression equations was used to test the

424

DIAZ, GLASS, ARNKOFF, AND TANOFSKY-KRAFF

Table 2

Intercorrelations Among Predictor Variables

Variable

1.LSAT

2. STAI-Trait

3. PRCA-24

4. RTT

SES-EX

5. Affective control

6. Cognitive control

7. Performance

SES-OA

8. Affective control

9. Cognitive control

10. Performance

STAI-State

11. Exam

12. Oral argument

13. CPNT, Negative

thoughts

14. SISST-PS, Negative

thoughts

2

3

4

5

6

7

10

-.01

.00

44**

-.11

.50**

39**

.03

-.36**

-.23**

_ 33**

11

12

13

-.07

-.33**

-.22*

-.35**

-.03

-.35**

-.13

-.24**

-.18

-.25*

-.58**

-.21

-.08

-.20

-.46**

-.33**

-.01

-.27*

-.40**

-.18

.05

.32**

29**

.39**

.81**

.77**

.76**

.36**

.30*

.24

.32*

.35**

.26

.31*

.32**

.36**

-.32**

-.33**

-.33**

-.14

-.08

-.01

.77**

.84**

.72**

-.36**

-.34**

-.33**

- . 4 1 * * -.24

-.30* -.29*

-.37* -.30*

8

9

10

11

12

13

.17 -.04

.17

.33**

.22*

.21*

.21*

.37**

.13

-.29**

-.33**

-.38**

.65**

.09

14

.20

.30**

.34**

.32**

-.20

-.24*

-.21

-.24

-.28

-.30*

.32**

.55**

.37*

14

Note. LSAT = Law School Aptitude Test; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; PRCA-24 = Personal Report of Communication Apprehension-24;

RTT = Reactions To Tests scale; SES = Self-Efficacy Scales (EX = exam, OA = oral argument); CPNT = Checklist of Positive and Negative Thoughts;

SISST-PS = Social Interaction Self-Statement TestPublic Speaking.

* p < . 0 5 . **/><.01.

models. Each of the two performance outcome scores was analyzed separately. All predictors for each dependent variable were

entered simultaneously on the same step. For each model, LSAT

score was used as the main ability variable, because preliminary

analyses and prior research (Wightman, 1993) indicate that the

LSAT is likely to be a better predictor of academic performance

than undergraduate GPA alone.

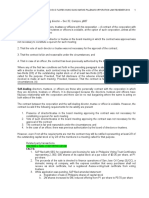

Contracts exam model. The path analysis predicting the contracts exam grade is shown in Figure 1, along with the R2 for each

endogenous variable. For the antecedent variables, only trait anxiety was predictive of self-efficacy, relating inversely to selfefficacy for cognitive control, affective control, and performance.

Although there was no significant relationship between LSAT

score and self-efficacy for performance, LSAT scores were

strongly predictive of the final exam grade. Test anxiety was found

not to be predictive of self-efficacy for the contracts exam. For the

preperformance-phase variables, self-efficacy for control of cognitions was significantly related to the SOM ratio of thoughts

during the contracts exam. The more self-efficacy for cognitive

control 4 weeks before final exams, the more positive the ratio of

thoughts during the contracts exam. However, there was no relationship between self-efficacy for affective control and state anxiety immediately following the final exam. Further, self-efficacy

for performance was not related to performance outcome.

With regard to the performance-phase variables, SOM was

significantly related to state anxiety in that the more positive the

SOM ratio, the lower the state anxiety. State anxiety was negatively, but not significantly, related to exam grade, and the SOM

ratio was unrelated to performance. When negative thoughts were

used in place of the SOM ratio as the measure of cognition in the

model, no substantive changes were found.

Oral argument path model. The model and results for the oral

argument are shown in Figure 2. For the antecedent variables,

LSAT score was not predictive of level of self-efficacy for performance. However, the PRCA-24 was significantly related to

self-efficacy in that the higher the communication apprehension,

the lower the self-efficacy for performance, affective control, and

cognitive control.

In the preperformance phase, the three self-efficacy subscales

were differentially effective in predicting performance-phase constructs. The greater the self-efficacy for affective control, the lower

the state anxiety. However, self-efficacy for performance was not

related to oral argument score.

Findings in the performance phase indicated that negative

thoughts were significantly related to state anxiety in that the more

frequent the negative thoughts, the higher the state anxiety. Similarly, the higher the level of state anxiety, the lower the oral

argument score, although the frequency of negative thoughts alone

was not related to performance.

When we substituted the SOM ratio for negative thoughts as the

measure of cognition in the path analysis, the relationship between

preperformance- and performance-phase variables shifted slightly.

State anxiety remained the only predictor of performance, /3 =

.47, p < .05, although it was not as strong a predictor as when

negative thoughts were included in the model. SOM, like negative

thoughts, did not predict outcome, /3 = - . 0 3 , p < .88, but SOM

was an even stronger predictor of state anxiety, j3 = .59, p <

.001, than were negative thoughts. However, the predictiveness of

self-efficacy for affective control and for cognitive control

changed. When SOM was used as the measure of cognition,

self-efficacy for cognitive control became a significant predictor of

SOM, /3 = .35, p < .05, whereas self-efficacy for affective control

was no longer a significant predictor of state anxiety, /3 = .19,

p < .16.

Given the correlational findings, a separate path was also calculated using positive thoughts as the cognitive measure. Self-

425

PREDICTION OF LAW STUDENT PERFORMANCE

-.16

EXAM

GRADE

STATE

ANXIETY

TRAIT

ANXIETY

SELF-EFFICACY FOR

AFFECTIVE

CONTROL

I-.65

/-.04

STATE-OFMIND

RATIO

TEST ANXIETY

.17

SELF-EFFICACY FOR

COGNITIVE

CONTROL

Figure 1. Path model for final exam performance. R2 for self-efficacy = .13 (performance), .13 (affective

control), .11 (cognitive control); R2 for state anxiety = .47; for state-of-mind ratio = .13; for exam grade = .12.

**p < .01.

efficacy for cognitive control emerged as a significant predictor of

positive thoughts, /3 = .44, p < .01. Self-efficacy for affective

control no longer predicted state anxiety, )3 = .10, p < .49, but

positive thoughts were a strong predictor, /3 = .57, p < .001,

such that the higher the frequency of positive thoughts, the lower

the level of state anxiety. State anxiety was no longer a significant

predictor of outcome, /3 = .26, p < .16.

Discussion

In summary, results of the path analysis for the exam model

revealed that among the antecedent variables, only LSAT score

directly predicted performance. Trait anxiety predicted selfefficacy for cognitive control, which was predictive of SOM ratio,

which in turn predicted state anxiety. Neither the SOM ratio nor

state anxiety, however, predicted performance on the exam. In the

oral-argument model, a clear path of significant predictors could

be traced from communication apprehension to self-efficacy for

affective control, to state anxiety, and finally to oral argument

score. In addition, negative thoughts were also predictive of state

anxiety. Specific findings relevant to the models will now be

discussed.

man, 1993), the LSAT was a reliable predictor of exam performance (and of first-year class rank, as well). The LSAT is a

standardized test designed to assess the ability to deal with novel

situations and problems with logical and careful analysis (Powers,

1982). Not surprisingly, it did not correlate with oral argument

performance, as standardized tests are poorer predictors of clinical

performance in law school (Powers, 1982). The two models also

differed with regard to the other antecedent variables. As hypothesized in the exam model, trait anxiety was predictive of all three

self-efficacy domains. Although test anxiety was not predictive of

self-efficacy in the exam model, communication apprehension was

predictive of self-efficacy for the oral argument. This unexpected

result in the exam model may be due to the overlapping variance

of trait and test anxiety. It should be noted that simple correlations

did show significant inverse relationships between test anxiety and

self-efficacy. Trait anxiety was not included as an antecedent

variable in the oral argument model, because the much smaller

number of participants necessitated fewer variables in the analysis.

In this case, the specific dispositional anxiety measure of communication apprehension was highly predictive of all three selfefficacy domains.

Antecedent-Phase Predictions

Preperformance-Phase Predictions

Findings with regard to the LSAT were as expected in the exam

model. Consistent with the literature (e.g., LSAC, 1996; Wight-

With regard to the preperformance-phase variables, the two

models were similar in that self-efficacy for performance did not

426

DIAZ, GLASS, ARNKOFF, AND TANOFSKY-KRAFF

V.08

.06

SELF-EFFICACY FOR

PERFORMANCE

STATE

ANXIETY

-.47*

-.51*

ORAL

ARGUMENT

SCORE

-.33}

-.61**

COMMUNICATION

APPREHENSION

SELF-EFFICACY FOR

AFFECTIVE

CONTROL

/.12

NEGATIVE

THOUGHTS

-.50**

-.26-tSELF-EFFICACY FOR

COGNITIVE

CONTROL

Figure 2. Path model for oral argument performance. R2 for self-efficacy = .19 (performance), .38 (affective

control), .25 (cognitive control); R2 for state anxiety = .35; for negative thoughts = .07; for oral argument

score = .23. t/> < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

predict performance, contrary to most studies reviewed by Multon

et al. (1991). However, a recent path-analytic study by Rouxel

(1999) also failed to support a direct (or indirect) effect of selfefficacy on academic performance. The lack of predictive ability in

the exam model is consistent with social cognitive theory stating

that past and vicarious experiences influence the formation of

self-efficacy expectations (Bandura, 1977). Participants had no

prior experience with law school final exams, which are different

from any they had taken as undergraduates, and had no prior

performance feedback in the course. Later in law school, perhaps

even by the end of the first year, after students have had experience

with a number of exams, self-efficacy for performance would be

expected to be related more strongly to exam outcome.

For the oral argument, although some students had done an

optional oral argument in their first semester, most were still

relative novices. The earlier argument was also before a panel of

upper level students, not actual attorneys and judges from the

community. Thus, the lack of specific past experience may have

led to weaker relationships between self-efficacy and outcome.

As hypothesized, self-efficacy for affective control was a significant predictor of state anxiety in the oral argument model, but

it failed to predict in the exam model. The opposite was true for

self-efficacy for cognitive control, which predicted cognition (the

SOM ratio) in the exam model but showed only a trend toward

predicting negative thoughts during the oral argument. When SOM

was substituted as the cognitive measure in the oral argument

model, however, the path to state anxiety became the same as for

the exam model. This finding is consistent with that of Arnkoff et

al. (1992), who found that self-efficacy to control thoughts and

anxiety predicted the SOM ratio, which in turn predicted state

anxiety.

Performance-Phase Predictions

Positive thoughts appeared to play an important role in oral

argument performance. The mean SOM ratio of positive-topositive plus negative thoughts was .71, considerably greater than

that of .59 during the exam. Although negative thoughts did

predict state anxiety in the oral argument model, the strongest

relationships between cognition and state anxiety occurred when

positive cognitions were included, either as part of the SOM ratio

or alone. In addition, there was a trend in the path model for

positive thoughts to predict performance, and the simple correlation was significant.

The importance of positive thoughts in this model is different

from that found in most previous literature, which has primarily

found a debilitating impact of negative thoughts (Arnkoff & Smith,

1988; Kendall, 1984). The high SOM ratio for the oral argument

may be a function of this task, which, unlike exams, was one of the

few things students did during their first year in which they could

feel like a practicing attorney. Further, it had no consequences for

course grades, and students had been told that to be a convincing

427

PREDICTION OF LAW STUDENT PERFORMANCE

advocate, they had to believe in their case and feel it was winnable.

The strongest correlate of state anxiety was the SOM ratio (-.63),

suggesting that it is important to take positive as well as negative

thoughts into account.

The fact that state anxiety was not predictive of exam grades

(and only LSAT scores predicted exam performance) is consistent

with some previous literature. Although anxiety may indirectly

affect performance, findings on the relationship of test anxiety and

performance have been mixed (Brown & Nelson, 1983; Hunsley,

1985). Arnkoff et al. (1992) also failed to find relationships between graduate students' thoughts and anxiety and their performance on doctoral dissertation orals, whereas ability measures

such as Graduate Record Examination (GRE) scores and graduate

GPA were highly correlated with rated performance. In contrast,

the oral argument model showed state anxiety to be highly related

to judges' ratings of oral argument performance, just as Glass et al.

(1995) found in their study of soldiers taking a career-related oral

examination before a panel of their superiors. Evaluations of

performance on public-speaking tasks like the oral argument

largely depend on the speaker's appearing calm and competent.

Effective cognitive control for the oral argument may have consisted of generating positive thoughts that enabled students to feel

less anxious. They may have thus appeared less anxious, more

enthusiastic, and more persuasive, which in turn may have affected

judges' ratings of the quality of their performance.

Implications for Future Research and Legal Education

This study offers a unique examination of models predicting

performance on two law school tasks, with different paths for

exams and oral argument. It may be that for academic exams,

which in law school essentially determine students' grades in each

course, standardized aptitude tests such as the LSAT serve as the

most reliable predictor of performance. The LSAT was also the

strongest correlate of first-year class rank. Thus the stress and

anxiety experienced by first-year law students so often documented in the literature (see Dammeyer & Nunez, 1999), although

causing significant distress, did not appear to have an impact on

their academic performance. In contrast, dispositional anxiety variables and cognitions may be the most useful predictors when the

performance task, in this case an oral argument, is one in which

outcome is in part a function of how calmly and confidently

individuals can present themselves.

Although LSAT and undergraduate GPA did correlate significantly with first-year class rank, the models explained relatively

little of the variance in performance. Thus some of the factors that

were examined in a study of variables predicting passage of the bar

exam, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, need to work while

in law school, and academic expectations (Wightman, 1998) could

be important additions to the predictive power of our model. Other

possible factors could be students' ability to understand what is

valued and what is not (i.e., knowing "how to play the game"; G.

Niedzielko, personal communication, June 15, 2000), as well as

good analytical and writing skills (G. Watson, personal communication, July 5, 2000).

Future studies might also focus more on the role of positive

thoughts, as they were significantly related to oral argument performance in the present investigation. Additionally, it could be

advantageous to examine oral arguments with academic conse-

quences, in which successful performance is seen as much more

important than in the present study. Finally, it may prove useful to

look at the strength and generality of self-efficacy expectations

later in the course of law school, after students have taken several

exams, and note the role of past performance on the development

of self-efficacy for law school success.

The results of this study have implications for law students

experiencing anxiety, as well as for law school programs interested

in furthering the welfare of their students. It has been suggested

that law schools initiate stress management programs (Gutierrez,

1985; McCleary & Zucker, 1991), and based on the differential

findings from the two models in the present study, the approaches

may need to vary depending on the type of task generating anxiety.

Results of the exam model suggest that the focus might be on

identifying cognitive patterns and negative thoughts that serve as

triggers for anxiety. The goal of such an intervention would be to

help students challenge and develop a sense of control over debilitative cognitions, in order to minimize distress (e.g., Beck &

Burns, 1979).

However, to improve exam performance, academic interventions (such as tutoring and study-skills training) may be necessary.

For example, Wangerin (1988) has suggested that students be

taught metacognitive skills in time management, efficient reading,

note taking, and reviewing material. Teaching specific lawyering

skills, such as legal analysis and research, can be based on principles of cognitive science in order to impart to students the

conceptual tools needed to analyze cases and apply rules of law

(Blasi, 1995). In addition, students could be better prepared for the

novel experience of taking law school exams if they were given

practice on this type of task before the end of the semester, thus

building a sense of self-efficacy that might be related to later

performance. The recent movement toward creating academic

support programs (ASPs) to help minority and nontraditional students acquire necessary metacognitive skills incorporates many of

these strategies (Knaplund & Sander, 1995; Lustbader, 1997).

From the oral argument model, goals for assisting law students

who have difficulties in public-speaking situations could center on

maximizing performance by reducing anxiety. Law school administrators could help by actively sanctioning and encouraging students to seek out counseling services (Carney, 1990; Gutierrez,,

1985). Cognitive-behavioral approaches (St. Lawrence, McGrath,

Oakley, & Suit, 1983) might again be especially useful in targeting

communication apprehension, so that students could better manage

their anxiety and thus increase their self-efficacy for affective

control, resulting in lower anxiety during oral argument and better

performance. Making videotaped oral arguments with judges' ratings available for student observation might also be beneficial for

reducing communication apprehension, as would giving first-year

law students the opportunity to videotape their own practice arguments and review them with faculty or advanced students. Improved academic performance and lower levels of anxiety could

make the law school experience a more positive and valuable one

for the many students who now experience the law school environment as difficult, stressful, and debilitative.

References

Arch, E. C. (1992). Affective control efficacy as a factor in willingness to

participate in a public performance situation. Psychological Reports, 71,

1247-1250.

428

DIAZ, GLASS. ARNKOFF, AND TANOFSKY-KRAFF

Arnkoff, D. B.. Glass, C. R., & Robinson, A. S. (1992). Cognitive processes, anxiety, and performance on doctoral dissertation oral examinations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39, 382-388.

Arnkoff. D. B., & Smith, R. J. (1988). Cognitive processes in test anxiety:

An analysis of two assessment procedures in an actual test. Cognitive

Therapy and Research, 12, 425-439.

Auerbach, C. A. (1984). Legal education and some of its discontents.

Journal of Legal Education, 34, 4372.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral

change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura. A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social

cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura. A. (1988). Self-efficacy conception of anxiety. Anxiety Research, I, 77-98.

Beatty, M. J. (1986). Communication apprehension and general anxiety.

Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 1, 209-212.

Beck, A. T., & Emery, G. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A

cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books.

Beck. P. W., & Burns, D. (1979). Anxiety and depression in law students:

Cognitive intervention. Journal of Legal Education, 30, 270-290.

Beidel. D. C . Turner. S. M , & Dancu, C. V. (1985). Physiological,

cognitive, and behavioral aspects of social anxiety. Behaviour Research

and Therapy, 23. 109-117.

Beidei. D. C . Turner, S. C , Jacob, R. G., & Cooley, M. R. (1989).

Assessment of social phobia: Reliability of an impromptu speech task.

Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 3, 149-158.

Blasi. G. L. (1995). What lawyers know: Lawyering expertise, cognitive

science, and the functions of theory. Journal of Legal Education, 45,

313-397.

Boyle. R. A.. & Dunn, R. (1998). Teaching law students through individual

learning styles. Albany Law Review, 62, 213-247.

Brown, S. D., & Nelson, T. L. (1983). Beyond the uniformity myth: A

comparison of academically successful and unsuccessful test-anxious

college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 363-374.

Bruch. M. A. (1981). Relationship of test-taking strategies to test anxiety

and performance: Toward a task analysis of examination behavior.

Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5, 41-56.

Carney, M. E. (1990, Spring-Summer). Narcissistic concerns in the educational experience of law students. The Journal of Psychiatry &

Law. IX, 9-34.

Covington, M. V., & Omelich, C. L. (1990). Achievement dynamics: The

interaction of motives, cognitions, and emotions over time. Anxiety

Research. I. 165-183.

Dammeyer. M. M , & Nunez, N. (1999). Anxiety and depression among

law students: Current knowledge and future directions. Law and Human

Behavior. 23. 55-73.

Deffenbacher, J. L. (1986). Cognitive and physiological components of test

anxiety in real-life exams. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 635644.

Frierson, H. T., & Hoban. D. (1987). Effects of test anxiety on performance

on the NBME Part I examination. Journal of Medical Education, 62,

431-433.

Galassi, J. P., Frierson, H. T., & Sharer, R. (1981). Behavior of high,

moderate, and low test anxious students during an actual test situation.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 51-62.

Glass, C. R., & Arnkoff, D. B. (1994). Validity issues in self-statement

measures of social phobia and social anxiety. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 32, 255-267.

Glass. C. R., & Arnkoff, D. B. (1997). Questionnaire methods of cognitive

self-statement assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 65, 911-927.

Glass. C. R.. Arnkoff, D. B., Wood, H., Meyerhoff, J. L., Smith, H. R.,

Oleshansky. M. A.. & Hedges, S. M. (1995). Cognition, anxiety, and

performance on a career-related oral examination. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 42, 47-54.

Glass, C. R., Merluzzi, T. V., Biever, J. L., & Larsen, K. H. (1982).

Cognitive assessment of social anxiety: Development and validations of

a self-statement questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6,

37-55.

Gutierrez, J. (1985). Counseling law students. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 64, 130-133.

Hunsley, J. (1985). Test anxiety, academic performance, and cognitive

appraisals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 678-682.

Kendall, P. C. (1984). Behavioral assessment and methodology. In C. M.

Franks, G. T. Wilson, P. C. Kendall, & K. D. Brownell (Eds.), Annual

review of behavior therapy (Vol. 10, pp. 47-86). New York: Guilford

Press.

Kent, G., & Jambunathan, P. (1989). A longitudinal study of the intrusiveness of cognitions in test anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27,

43-50.

Kissam, P. C. (1989). Law school examinations. Vanderbilt Law Review, 42, 433-504.

Knaplund, K. S., & Sander, R. H. (1995). The art and science of academic

support. Legal Education, 45, 157-234.

Law School Admissions Council. (1996). LSAT/LSADS registration and

information book. Newtown, PA: Author.

Linn, R. L., & Hastings, C. N. (1984). A meta analysis of the validity of

predictors of performance in law school. Journal of Educational Measurement, 21, 245-259.

Lustbader, P. (1997). From dreams to reality: The emerging role of law

school academic support programs. University of San Francisco Law

Review, 31, 839-860.

McCleary, R., & Zucker, E. L. (1991). Higher trait- and state-anxiety in

female law students than male law students. Psychological Reports, 68,

1075-1078.

McCroskey, J. C. (1984). Self-report measurement. In J. A. Daly & J. C.

McCroskey (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence and

communication apprehension (pp. 81-94). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

McCroskey, J. C. (1993). Introduction to rhetorical communication (6th

ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

McCroskey, J. C , Beatty, M. J., Kearney, P., & Plax, T. G. (1985). The

content validity of the PRCA-24 as a measure of communication apprehension across communication contexts. Communication Quarterly, 33,

165-173.

Mclntosh, D. N., Keywell, J., Reifman, A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1994).

Stress and health in first-year law students: Women fare worse. Journal

of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 1474-1499.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of selfefficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation.

Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 30-38.

Ozer, E. M., & Bandura, A. (1990). Mechanisms governing empowerment

effects: A self-efficacy analysis. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 58, 472-486.

Powers, D. E. (1982). Long-term predictive and construct validity of two

traditional predictors of law school performance. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 74, 568-576.

Rouxel, G. (1999). Path analysis of the relations between self-efficacy,

anxiety and academic performance. European Journal of Psychology of

Education, 14, 403-421.

Sarason, I. G. (1982). Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: Reactions

To Tests. Arlington, VA: Office of Naval Research.

Sarason, I. G. (1984). Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: Reactions

To Tests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 929-938.

Schick, S. R. (1996). Creating lawyers: The law school experience. The

Compleat Lawyer, 13(2), 46-49.

Schwartz, R. M., & Garamoni, G. L. (1989). Cognitive balance and

psychopathology: Evaluation of an information processing model of

PREDICTION OF LAW STUDENT PERFORMANCE

positive and negative states of mind. Clinical Psychology Review, 9,

271-294.

Seipp, B. (1991). Anxiety and academic performance: A meta-analysis of

findings. Anxiety Research, 4, 27-41.

Shanfield, S. B., & Benjamin, G. A. H. (1985). Psychiatric distress in law

students. Journal of Legal Education, 35, 65-75.

Smith, R. J., Arnkoff, D. B., & Wright, T. L. (1990). Test anxiety and

academic competence: A comparison of alternative models. Journal of

Counseling Psychology, 37, 313-321.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A.

(1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA:

Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D., & Rickman, R. L. (1990). Assessment of state and trait

anxiety. In N. Sartorius (Ed.), Anxiety: Psychobiological and clinical

perspectives (pp. 69-83). New York: Hemisphere.

St. Lawrence, J. S., McGrath, M. L., Oakley, M., & Suit, S. C. (1983).

Stress management training for law students: Cognitive-behavioral intervention. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 1, 101-110.

429

Stopa, L., & Clark, D. M. (1993). Cognitive processes in social phobia.

Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 255-267.

Turner, S. M., & Beidel, D. C. (1985). Empirically derived subtypes of

social anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 16, 384-392.

Wangerin, P. T. (1988). Learning strategies for law students. Albany Law

Review, 52, 471-528.

Wightman, L. F. (1993, December). Predictive validity of the LSAT: A

national summary of the 1990-1992 correlation studies (Research Rep.

No. 93-05). Newtown, PA: Law School Admission Council.

Wightman, L. F. (1998). LSAC national longitudinal bar passage study.

Newtown, PA: Law School Admission Council.

Zohar, D. (1998). An additive model of test anxiety: Role of exam-specific

expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 330-340.

Received August 17, 1999

Revision received July 18, 2000

Accepted October 8, 2000

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- BarangayS in General TriasDocument2 pagesBarangayS in General TriasLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Jurisprudence On Human Trafficking - Research SJDHSJDHDFDocument3 pagesJurisprudence On Human Trafficking - Research SJDHSJDHDFLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- A) CIR Vs Sony PhilippinesDocument2 pagesA) CIR Vs Sony PhilippinesLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- 43) Calaagan Golf Club vs. Sixto ClementeDocument2 pages43) Calaagan Golf Club vs. Sixto ClementeLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographyLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Affidavit of LossDocument2 pagesAffidavit of LossLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Nature Is A WhoreDocument1 pageNature Is A WhoreLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Government Procurement Reform Act SummaryDocument24 pagesGovernment Procurement Reform Act SummaryAnonymous Q0KzFR2i0% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Strictly Privileged and Confidential: MemorandumDocument3 pagesStrictly Privileged and Confidential: MemorandumLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- E. CIR vs. Mirant (Phils) Operations CorporationDocument2 pagesE. CIR vs. Mirant (Phils) Operations CorporationLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Major Scale Modes Three Notes Per StringDocument1 pageMajor Scale Modes Three Notes Per StringLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- 6) Ty Vs Filipinas Compania de SegurosDocument1 page6) Ty Vs Filipinas Compania de SegurosLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Garcia Vs Drilon (Petitioner and SC)Document3 pagesGarcia Vs Drilon (Petitioner and SC)Lanz Olives80% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 19) Advance Paper Vs ArmaDocument2 pages19) Advance Paper Vs ArmaLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Olives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesOlives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Complaint For Support SampleDocument6 pagesComplaint For Support SampleLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- 1) Public Company - Rule 3.1 (M)Document6 pages1) Public Company - Rule 3.1 (M)Lanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Part IX EMPLOYER LOCKOUTDocument6 pagesPart IX EMPLOYER LOCKOUTLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Loan AgreementDocument4 pagesReal Estate Loan AgreementLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Advanced Legal Writing Course OverviewDocument11 pagesAdvanced Legal Writing Course OverviewLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- SSS VsDocument2 pagesSSS VsLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Olives Labor Law Reflection PaperDocument5 pagesOlives Labor Law Reflection PaperLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Conclusion Draft Why Should We Not Join TPPDocument2 pagesConclusion Draft Why Should We Not Join TPPLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- RemindersDocument9 pagesRemindersLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- CLFR Nov 29 FinalDocument197 pagesCLFR Nov 29 FinalLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Mariwasa union registration upheldDocument3 pagesMariwasa union registration upheldLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Olives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesOlives, Lanz Aidan L. Olives 31 March 2016 11382597 Special Proceedings Reflection PaperLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Olives Week 1 DigestDocument8 pagesOlives Week 1 DigestLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- RemindersDocument9 pagesRemindersLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- CIR Wins Tax Remedies CasesDocument37 pagesCIR Wins Tax Remedies CasesLanz OlivesNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 MCQDocument44 pagesUnit 5 MCQcreepycreepergaming4No ratings yet

- HIP Online Reporting Template - 9 JUNEDocument23 pagesHIP Online Reporting Template - 9 JUNEpejabatNo ratings yet

- A2 UNIT 4 Flipped Classroom Video WorksheetDocument1 pageA2 UNIT 4 Flipped Classroom Video WorksheetАлена СылтаубаеваNo ratings yet

- Weekly Report, Literature Meeting 2Document2 pagesWeekly Report, Literature Meeting 2Suzy NadiaNo ratings yet

- Wac ApplicationDocument2 pagesWac Applicationapi-242989069No ratings yet

- Person Resididng Outside ManipurDocument21 pagesPerson Resididng Outside ManipurNguwruw Chungpha MoyonNo ratings yet

- Undertaking Cum Indemnity BondDocument3 pagesUndertaking Cum Indemnity BondActs N FactsNo ratings yet

- BA 301 Syllabus (Summer 2018) Chuck Nobles Portland State University Research & Analysis of Business ProblemsDocument11 pagesBA 301 Syllabus (Summer 2018) Chuck Nobles Portland State University Research & Analysis of Business ProblemsHardlyNo ratings yet

- Memorial ProgramDocument18 pagesMemorial Programapi-267136654No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Informational TextDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Informational TextEdwin Trinidad100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Table of Specification (TOS)Document2 pagesTable of Specification (TOS)Charlene FiguracionNo ratings yet

- IT1 ReportDocument1 pageIT1 ReportFranz Allen RanasNo ratings yet

- OmorakaDocument7 pagesOmorakaDamean SamuelNo ratings yet

- Science and TechnologyDocument4 pagesScience and TechnologysakinahNo ratings yet

- F18Document4 pagesF18Aayush ShahNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Quarter 4 Module 5 Lesson 1Document2 pagesPractical Research 2 Quarter 4 Module 5 Lesson 1juvy abelleraNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of student teachers towards teaching professionDocument6 pagesAttitudes of student teachers towards teaching professionHuma Malik100% (1)

- Sptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4Document12 pagesSptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4MarivicNovencidoNicolasNo ratings yet

- Punjabi MCQ Test (Multi Choice Qus.)Document11 pagesPunjabi MCQ Test (Multi Choice Qus.)Mandy Singh80% (5)

- Counselling Psychology NotesDocument7 pagesCounselling Psychology NotesYash JhaNo ratings yet

- WQuest Itools 2 Tests 5Document1 pageWQuest Itools 2 Tests 5Magdalena QuirogaNo ratings yet

- Sanjeev Resume UpdatedDocument2 pagesSanjeev Resume UpdatedSanjeevSonuNo ratings yet

- Landscape Architect Nur Hepsanti Hasanah ResumeDocument2 pagesLandscape Architect Nur Hepsanti Hasanah ResumeMuhammad Mizan AbhiyasaNo ratings yet

- Budget Proposal TVL SampleDocument4 pagesBudget Proposal TVL SampleScarlette Beauty EnriquezNo ratings yet

- San Antonio Elementary School 3-Day Encampment ScheduleDocument2 pagesSan Antonio Elementary School 3-Day Encampment ScheduleJONALYN EVANGELISTA100% (1)

- PYP and the Transdisciplinary Themes and Skills of the Primary Years ProgramDocument6 pagesPYP and the Transdisciplinary Themes and Skills of the Primary Years ProgramTere AguirreNo ratings yet

- Describing Colleagues American English Pre Intermediate GroupDocument2 pagesDescribing Colleagues American English Pre Intermediate GroupJuliana AlzateNo ratings yet

- 39-Article Text-131-1-10-20191111Document9 pages39-Article Text-131-1-10-20191111berlian gurningNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Peer Pressure To The Grade 10 Students of Colegio San Agustin Makati 2018-2019 That Will Be Choosing Their Respective Strands in The Year 2019-2020Document5 pagesThe Effect of Peer Pressure To The Grade 10 Students of Colegio San Agustin Makati 2018-2019 That Will Be Choosing Their Respective Strands in The Year 2019-2020Lauren SilvinoNo ratings yet

- Research 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Document20 pagesResearch 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Rutchel100% (2)