Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Murray S. Davis - Frame Analysis An Essay On The Organization of Experience.

Uploaded by

contscribd11Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Murray S. Davis - Frame Analysis An Essay On The Organization of Experience.

Uploaded by

contscribd11Copyright:

Available Formats

Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience.

by Erving Goffman

Review by: Murray S. Davis

Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 4, No. 6 (Nov., 1975), pp. 599-603

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2064021 .

Accessed: 20/06/2014 04:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Contemporary Sociology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW

SYMPOSIUM

Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, by ERVINGGOFFMAN.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University

Press, 1974. 586 pp. $12.50 cloth.

MURRAYS. DAVIS

Universityof California,San Diego

Goffmanhas devoted most of his work to

underminingthe integrityof some accepted

social entities (like the individual) and the

legitimacy of others (like the total institution). Frame Analysis is no exception, except in thisbook Goffmanattemptsto undermine everyday reality itself, particularly

James' and Schutz' claim that it is the prime

reality,more fundamentalthan other realities

(like dreams or play). (One wonders what

Goffmanwill subtlysubvertnext. Watch out,

God!)

Goffmanbegins by dividingthe world into

an empirical part-a "strip"-which he definesas "any arbitraryslice or cut from the

stream of ongoing activity" (p. 10), and a

subjective part-a "frame"-which he definesas the "principlesof organizationwhich

govern events-at least social ones-and our

subjective involvementin them" (p. 10-11).

(In his later, concrete applications of frame

analysis, however, he is sometimes unclear

whether frames organize the individual experience of events, as he claims (p. 13), or

whetherthey determinethe actual social organization of the events themselves.) We

"frame" "strips" of activityby seeing them

as natural ("unguided events") or social

("guided doings")-the two fundamental

frames;or as fantasiedor faked-two of the

many instancesof secondaryframesGoffman

discusses.

Frame analysis seems to have two aspects,

which I will call the cellular and the concentric. The cellular aspect of frame analysis

involves describingthe membranearound an

activity-the spatial and temporalbracketsof

each particularframe.For instance,the theaterframe (which Goffmananalyzes in greater

detail than other frames) usually has a sharp

beginning and ending as well as a highly

definedspatial location. Cellular frameanalysis also involves distinguishing

the nucleus of

an activityfrom its surroundingcytoplasmthe innerofficialevents (the play itself) from

the outer spectacular occasion (going to the

theater). One of Goffman's most incisive

conceptual scalpels dissects framed strips of

activityinto"tracks"or "channels"-a "main"

or "story"line at the centerof the frameand

several subordinatelines "out of frame" (disattended,directional,overlaid, and concealed

lines).

The concentric (onion skin) aspect of

frame analysis involves discriminatingthe

various levels or "laminations" that frame a

strip of activity and specifying the ways

natural and social frames (basic) are transformed into other, less fundamentalframes.

One kind of frame transformationGoffman

calls "keying," which he defines as "the set

of conventionsby which a given activity,one

already meaningfulin termsof some primary

framework, is transformedinto something

patterned on this activitybut seen by the

participantsto be somethingquite else" (p.

43-44). We key a stripof activityby making

it into a movie, novel, radio drama, theatrical

play, cartoon, puppet show, etc. A second

kind of frame transformationGoffmancalls

"fabrication,"which he defines as "the intentional effortof one or more individuals

to manage activity so that a party of one

or more others will be induced to have a

false belief about what it is that is actually

going on" (p. 83). We fabricate "benign"

frames by indulging in leg-pulls, practical

jokes, psychologyexperiments,etc.; we fabricate "exploitative" frames by engaging in

espionage, con games, frame-ups,etc. Keyed

frames,in which all parties are aware of the

differfromfabricatedframes,

transformation,

in which some parties are not aware of the

transformation.

Since laminated frames are blown up out

of fundamentalframes("upkeying"), theyare

more vulnerableto deflation("downkeying").

Keyed frames are liable to fall when they

are based on ambiguity(someone is not certain which frame to apply), error (someone

thought a bank was being robbed but it

was only a filmingof a bank robbery), or

dispute (the police contend someone dies

of a heart attack-a natural frame-but the

detectivecontendshe was murdered-a social

frame). Fabricated frames are liable to fall

when the deceived discover that the frame

theythoughtorganizedtheiractivitynaturally

599

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

600

CONTEMPORARY SOCIOLOGY: A JOURNALOF REVIEWS

was actually manufacturedby the deceivers ambiguities in his earlier work, particularly

artificially(someone findsout he was conned whether the dramaturgical perspective reout of his money). Since fabricatedframes veals that people spend most of their lives

are based on a differentialdistributionof actually "acting" or whether it merely proknowledge, they are more likely to break vides a vocabulary borrowed from theater

down and are more discreditingof theirsus- with which to describe unstaged aspects of

life. Goffman now asserts the former with

tainersthan keyed frames.

A collapsing frame has several conse- more confidenceand in more detail. He shows

quences. The collapse of the meaning of the how much of our talkingconsists of dramaframe may leave everyone disoriented.The tizing events that have happened to us. At

collapse of involvementin the frame may these points,at least, talk is similarto theater.

leave everyone either uninvolved (like a In dramatizingthese events, we do to ourbored audience at a bad play) or intensely selves what the playwrightdoes to his charinvolved with whoever or whateverdestroyed acters and the director does to his actors:

the frameand withtheirown lack of involve- withholdinformationto generatesuspense,rement and meaning. The latter,Goffmancalls hearse and replay, and even split ourselves

"negative experience-negative in the sense into several parts (e.g., through irony or

that it takes its character from what it is mocking) to reduce the responsibilityof our

not. . ." (p. 379). (In Goffman's model, present selves for what our past selves did

negative experience seems to be to normal or what our futureselves would like to doexperience as role distance is to role: the all this to gain audience appreciation for

individual can defineboth his experienceand ourselvesand sympathyfor our predicaments:

his self in termsof what theyare not.)

. . . what the individualspends most of his

Given the often greater intensityof exspoken momentsdoing is providingevidence

perience when it is negative,some peoplefor the fairnessor unfairnessof his current

particularlyentertainers-deliberatelymanipsituationand other grounds for sympathy,

approval, exoneration, understanding,or

ulate the deflationof frames to create this

And whathis listeners

amusement.

are primarintense, though negative, experience. Piranily obliged to do is to show some kind of

dello intentionallydisorientshis audience by

audienceappreciation.They are to be stirred

continually collapsing their theater frame

not to take action but to exhibitsigns that

(some of his characters discuss their own

theyhave been stirred.

acting or play at being membersof the audiFor what a speakerdoes usuallyis to preence). Many staged sportscontests,like telesent for his listenersa versionof what hapvised wrestlingor roller derby, intentionally pened to him. . . . Even if his purposeis to

involve theiraudience by continuallycollapspresentthe cold facts as he sees them,the

ing the game frame (some of the contestants

meanshe employsmay be intrinsically

theatrical, not because he necessarilyexaggeratesor

violate the rules outside of the referee'spurfollowsa script,but because he may have to

view of control), causing their audience to

engage in somethingthat is a dramatization

become attentiveless to the ruled actions than

-the use of such arts as he possesses to

to the infractions.Other people-particularly

reproducea scene, to replayit. He runs off

terroristsand counter-terrorists-deliberately a

tape of a past experience(p. 503-504).

manipulate the deflation of frames for the

more practical end of political disorienta- But whereas life is much like the stage, the

tion. Letter bombs (which destroy frame stage is not much like life. For in their

brackets as well as people) undermine the everyday lives people do not speak nearly

safety of the postal system,treason in high as well as characters on the stage, and the

places underminesfaith in the government, events they encounter are much more likely

agent provocateurs (by advocating extreme to be irrelevantand unconnected and much

unlawful activity) underminethe legitimacy less likelyto be critical and fateful(p. 557).

of revolutionarygroups.

Goffman's assertion that much of human

Before finishingwith his main concernlife consists of dramatizingbrings us to the

the nature of everydayreality-Goffman re- most eerie of his central themes-the disinturns to the topic that has preoccupied him tegration of the individual. Throughout his

since The Presentationof Self in Everyday works, Goffmandeepens the sociological enLife: the notion that we are all actors. In terprise;he is not content with the ordinary

fact, Goffman'ssecondarypurpose in writing sociological excavation of the individual

Frame Analysis seems to be to expand on which findsonly roles to be social, with the

his "dramaturgicalperspective"and to answer "true" self hidden beneath them. Goffman

some of the objections others have made to is much more "radical" than that. He be-

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW SYMPOSIUM

601

lieves the so-called person behind the mask In short,everydaylife is not the fundamental

of a social role to be just as much a sociologi- realm, but only one among many realms,for

cal construct as the mask itself. Man is it is composed of bits and pieces of these

sociological almost (as we shall see) to the otherrealms-its distinctnessbeing only that,

core, not just to the skin. The person essen- unlike these other realms, we believe that it

tially is the ways he animates a character is fundamental.

for himself (p. 547), and the ways he

*

*

*

separates himselffromhis role (p. 573). The

Frame Analysisprovidesa good vehicle for

frame of the situation in which the role is

performedgoverns how the self of the per- discussing the thoughtmodel underlyingalmost all of Goffman's work. Goffman has

formeris glimpsed:

be- been called many thingsfromsymbolicinterSelf, then,is not an entityhalf-concealed

hind events, but a changeable formulafor actionist to Machiavellian dramaturgist.But

managingoneself duringthem. Just as the while his writingsdo reveal the influenceof

currentsituationprescribesthe officialguise all these schools, behind them he is, more

behindwhichwe will conceal ourselves,so it essentially,a social constructionist.

He is alprovidesfor where and how we will show ways tryingto point out the social constructhrough. . . (p. 573-574).

tion of the seemingly natural-the human

Goffmandissolves the individualinto process fabricationof what most people considerpre(while holding constant the social structure fabricated (the individual, the ritual order,

roles). As a social constructionand norms of the situationout of which the institutions,

individualis continuallycreated) in much the ist, he begins by separating his subject into

same way that Garfinkeldissolves the social its basic elementsand then shows how these

structure and norms of the situation into elements are socially transformed (conprocess (while holdingconstantthe individual structed) into something more elaborate.

who continuallycreates them). Only our cul- Furthermore,he believes we can understand

turalideas about the ongoingbiological person how most people "naturally" construct a

give continuityto the individual'sintermittent social entity (the ways someone learns the

characteristics,

each of which he socially gen- role of a doctor) by looking at how some

erates anew from one situation to the next. people deceitfullyconstructthis social entity

Just as the individual is composed of a (the ways someone impersonatesa doctor).

number of loosely integratedcharacters and Thus Goffmanoften studies how something

roles, as well as the ways he shows distance (like reality) is faked to determinehow it is

fromthem,so Goffman-ever the sociological normallyfashioned.Assuming that all social

cubist-concludes that everydayreality,too, units,from roles to realities,are constructed

is not of one piece but consists of many implies that they are essentiallyarbitrary-a

loosely integrated frames-traffic systems, furtherfeature of his work which unsettles

ritual systems,bodily manipulatorysystems, many of his readers.

But what upsets them even more is the

religioussystems,etc. Moreover,much of our

for

ordinary activity is modeled after various other side of Goffman'sconstructionism,

ideal realms, found in folk tales, novels, Goffman is also a social destructionist.If

somethingis made, it can easily be unmade

advertisements,

myths,bibles, etc.:

So everydaylife . . . often seems to be a (whereas it is much harderto denaturesomelaminatedadumbration

of a patternor model thing natural). After showing how elaborate

that is itselfa typification

of quite uncertain social entities are built up, Goffman shows

realm status.. . . Life may not be an imita- how theyare vulnerableto breakingdown, a

tion of art,but ordinaryconduct,in a sense, painful process. (Our self-claimscan be disis an imitation

of the proprieties,

a gestureat credited,resultingin our shame; our sense of

theexemplary

and theprimalrealization realitycan be deflated,resultingin our disforms,

of these ideals belongsmore to make-believe orientation.)Social constructionsare not only

thanto reality(p. 562).

able to collapse; they are likely to, for

Of course we do not see everydaylife this small failures have great repercussions. If

way. We see it as unified,and we see a per- we can generate a whole self and a whole

son's everyday behavior as a "direct" indi- realityfrom a few small elements,then our

cation of his inner state, of the doer's being, whole self and our whole reality can coland of nothingelse. But this unifieddirect- lapse should its few small supports be

ness, Goffman affirms,is merely the dis- destroyed.In Goffmanland,both the individtinguishingfeature of the frame of every- ual and the universeare highlyunstable: one

day life, not a featureof everydaylife itself. embarrassing incident, one misinvolvement

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

602

CONTEMPORARY SOCIOLOGY: A JOURNALOF REVIEWS

can spread rapidly until one's whole self as

well as one's whole realityis broughtdown,

not only for the individualto whom it occurs

but also for everyoneconnected with him in

his vicinity.This repercussivemotifis prevalent throughoutGoffman's work. But note

that Goffmanfocuses only on negativerepercussions, not on positive ones. For instance,

he discusses how spreading embarrassment

destroys meaning but omits how spreading

charisma generatesmeaning. In this way he

makes the world even more desolate than it

actually is, thus expanding his personal

pessimisminto a universalprincipleof social

life.

Along side Goffman'sconstructionistsubjectivism,there runs a smaller positivistobjectiviststream-often concealed in footnotes

-which allows him an escape from the implicationsof the extremesubjectivistposition.

Goffman reveals his positivistside when he

asserts that beyond our socially constructed

world there is a real world impingingon it:

back from the brink of pansociologizingeverything.He is contentto have his cosmos and

doubt it too.

*

play

Since the means of self-presentation

so large a role in Goffman'sbooks, it is appropriate to say somethingabout Goffman's

own self-presentation.For a writer,self is

presentedthroughstyle.And Goffman'sstyle

is certainly unique. He has always written

to a differentdrummer from any other

sociologist. In his early work Goffman's

singular voice-which implied that behind

thosedead wordsa human being actuallylived

-was especially seductive to graduate students alternately bored and frightenedby

the insipid,impersonalstyle of most of their

mentors. So they are now greatlysaddened

by his writing's recent deterioration,much

discussed among Goffmanwatchersin hushed

and worriedtones. AlthoughGoffman'sideas

are as good as ever, stylisticdecline has set

in on the level of the sentence. Frame

to subordinateall sociologicalinterests Analysis (as well as Relations in Public) is

to this one-the issue of framedefinition-is a virtual thesaurus of stylistic gaffes and

dea bit much.It is a usefulmethodological

vice to assumethatsocial inquiryhas no con- gaucheries. If all the unnecessary "as to's,"

cern withwhat a physicalor biologicalevent "that's," "so as's," "in regard to's," and

mightbe "in itself,"but only interestin what other useless words and phrases were rethe membersof societymake of it. However, moved, the book would be 25% shorterwith

it is also necessaryto ask what the event no loss of substance and much gain in immakes societymake of it, and how it condi- pact. It is not clear why Goffman's style

tions social life in ways not appreciatedas has worsened. Perhaps its decay resultsfrom

such by participants

(p. 196n).

the well-known tendency of the successful

Outside the staged world there is an unstaged middle aged to thinktheirevery word worth

world in which "you need to findplaces for saying,perhaps fromthe loss of his previous

editor(s?) whose contributionto the appealcars to park and coats to be checked" (p. 1).

These positivistassumptions also appear in ing compressionof his earlier works has been

his earlierwork on self-presentation

where he unjustlyoverlooked. Perhaps he gets paid by

concludes that human beings must contain the word or (like most sociologists) has come

somethingnonsocial to animate their social to confuse obscuritywith profundity.Whatparts. Thus Goffmanseems to have encoun- ever the cause, let's hope the editingof Gofftered the same problem as Kant and other man's futurework becomes more disciplined.

Not that his style is entirelybad. There

moderate subjectivists:in Kant's case, where

to locate the noumena thatproduce the sensa- are still choice morselslike:

tionsour mind turnsintophenomena;in Goffsuch ceremonialization

of killing

Interestingly,

man's case, whereto locate the bio-psychologiis sometimescontrastedto the way in which

cal substrataof the performerwho performs

savages might behave, although I think it

our social charactersand where to locate the

would be hard to finda more savage practice

thanours-thatof bestowing

praiseupona man

bio-physical substrata of the world we turn

forholdinghimselfto thoseformsthatensure

into a social world of meaning. On these

an orderly,

styleto his execution

self-contained

metasociological assumptions,whatever cre(p. 355n).

ates socially or whateversomethingsocial is

In TV wrestling,the umpire'srulingis not

createdout of, cannot itselfbe social. Whether

merelyflouted,so that he must continuously

such nonsocial noumena are necessary on

come close to disqualifyingthe villian, but

other metasociological assumptions,whether

the umpirehimselfmay be directlyattackedwe can conceive of a person or a world even

a monstrousinfractionof framingrules-as

more sociological than Goffman dares to, I

thougha sentencewere to disregardits own

cannot say. But Goffman seems to draw

punctuationmarks(p. 417).

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW SYMPOSIUM

603

able member of the sociologist's lexicon,

referringto a recognizablegenre in the field.

Goffmanattemptsin Frame Analysisto codify

this genre-or more accurately,to begin the

work of codificationby delineatingpart of the

basic conceptual framework.The attemptinvites assessmentof the genre: an identification of the present state of the art and a

laying out of the unfinishedbusiness.

Judgedfromthe perspectiveof otherkinds

of sociology, this genre has certain apparent

vulnerabilities.These include the question of

its ability to generate testable propositions

about its chosen subject matter;the difficulties

of transmitting

analytictechniquefrommaster

to novice; and an undevelopedset of methods

for implementingits epistemology.

These are serious questions. Some may

suspect that they are unanswerable,that they

representfundamentalflaws in this way of

doing sociology. I argue here that they are

fully answerable although in some cases not

yet answered in any very satisfactoryway.

I believe they point to unfinishedbusiness

*

*

*

ratherthan fundamentalflaws.

For all its problemsand prolixity,I recomBefore I address these questions, it is

mend this book strongly.No sociologistsince necessaryto take a closer look at thatpart of

Simmel has tied together so wide a range the unfinishedbusinesswhich Goffmanunderof apparentlydisconnectedevents and activi- takes in Frame Analysis. This is a more amties withina single framework-fromnatural bitious book than Goffman's earlier work.

disasters (mine cave-ins) to verbal disasters Where he was satisfiedbefore to illuminate

(puns). He has extendedthe sociological ap- some strip of social activity by doing his

proach to realms seemingly immune to so- kind of analysis,here he takes a step back to

ciological penetration (hypnosis, possession, consider the enterpriseitself.It is, Goffman

insanity,drunkenness,childishness). And he concedes, "another go at analyzing fraud,

has broughtaspects of human existencefrom deceit, con games, shows of various kinds,

the edge of awareness to the center of sci- and the like" but here "I am tryingto order

entificconcern. Most of all, he has dignified my thoughtson these topics, tryingto conour ordinary insights into everyday life so structa general statement."

that we need not forget them but can inThe general statementconsists of a set of

corporate them into an ongoing scientific relatedconceptsthatcan be used in analyzing

corpus, allowing us to integrateour thought how people organize their experience. The

and our life,our work and our leisure-allow- question has deep ontologicalrootsbut for its

ing us, in the words of Stendhal, "the joy of translationinto a sociological question, Goffhaving one's passion as part of one's pro- man credits William James. Abandon the

fession."

bewilderingissue of what realityis and substitutethe manageable question, "Under what

circumstancesdo we think things are real?"

By studying the conditions under which a

WILLIAM A. GAMSON

sense of realness is generated,one can isolate

Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor

a fundamentalbut workable problem "having

If someone were to use the term "Goff- to do with the camera and not what it is the

manesque" to describe the work of a soci- camera takes picturesof."

ologist, most of us would readily understand

Goffman,then, is talkingabout the organwhat was meant. There would, no doubt, ization of experience-"something that an

be much fuzziness around the boundaries of individualactor can take into his mind"-and

this category, and we might well disagree not the organizationof society. He disclaims

about whetherwork near the edge was inside imperialisticdesigns on his colleagues' terrior out. Nevertheless,the term is a service- tory,grantingthe existence of a wide array

Unfortunatelythey come all too rarely.The

book is tedious to read-all 576 pages of

the paperback edition. The best way to

read Goffman I found is to plow through

him slowly, savoring his exquisite examples,

underliningthe "good parts." Rereading one's

underliningsbefore setting the book aside

allows one to appreciate his pearls and to

clarifyhis argumentwithoutbeing distracted

by the dross of his overly padded prose.

On the conceptual level, however,Goffmanis

still a master of the systematicand the interesting,whose combinationis no easy task.

Even on this level he sometimesstressessystem at the cost of interest,especially at the

beginning,but the ratio improvesas the book

continues. His most ingenious stylistictechnique is his reflexive asides in which he

applies frame analysis to the act of writing

books in general and his own book in particular, a technique carefully calculated to

induce the reader to have the "negative experience" he is discussing.

This content downloaded from 119.15.93.148 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 04:36:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- W. Weber - The History of The Musical CanonDocument10 pagesW. Weber - The History of The Musical CanonCelina Adriana Brandão Pereira100% (1)

- 1971 Elliott Versions of CreativityDocument14 pages1971 Elliott Versions of Creativitypacoperez2008100% (1)

- Native Speaker DeadDocument110 pagesNative Speaker Deadantigona_br100% (1)

- Gestalt Case Study - Group 2Document27 pagesGestalt Case Study - Group 2Ramyaa Ramesh67% (3)

- Being in The Body, Being in The Sound - A Tale of Modulating Identities and Lost PotentialDocument14 pagesBeing in The Body, Being in The Sound - A Tale of Modulating Identities and Lost Potentialsound hourNo ratings yet

- Weber (1994) The Intellectual Origins of Musical Canon in Eighteenth-Century EnglandDocument34 pagesWeber (1994) The Intellectual Origins of Musical Canon in Eighteenth-Century EnglandFederico BejaranoNo ratings yet

- Ah, I See! Metaphorical Thinking and The Pleasure of Re-CognitionDocument25 pagesAh, I See! Metaphorical Thinking and The Pleasure of Re-CognitionEduardo Souza100% (1)

- On Repetition in Ragnar Kjartansson and PDFDocument3 pagesOn Repetition in Ragnar Kjartansson and PDFBrett SmithNo ratings yet

- Nothingness Made VisibleDocument13 pagesNothingness Made VisiblemilkjuceNo ratings yet

- Postdramatic Theatre (Review) - Jeanne WillcoxonDocument3 pagesPostdramatic Theatre (Review) - Jeanne WillcoxonBülent GültekinNo ratings yet

- Gothic Voices - The Spirits of England and France, Vol. 1 PDFDocument17 pagesGothic Voices - The Spirits of England and France, Vol. 1 PDFIsrael100% (1)

- Bataille ExperienceDocument247 pagesBataille ExperienceMartinaNo ratings yet

- Music and Multimedia: Theory and HistoryDocument25 pagesMusic and Multimedia: Theory and HistoryAndrew RobbieNo ratings yet

- Peter Manuel - Music As Symbol, Music As SimulacrumDocument14 pagesPeter Manuel - Music As Symbol, Music As SimulacrumJos van Leeuwen100% (1)

- Performance Theory and The Study of RitualDocument30 pagesPerformance Theory and The Study of RitualDaniel Jans-PedersenNo ratings yet

- Zbikowski Music Theory Multimedia 2002Document10 pagesZbikowski Music Theory Multimedia 2002Sebastián Díaz CantoNo ratings yet

- Frame Analysis As A Discourse Method - Framing Climate Change Politics, Mat HopeDocument16 pagesFrame Analysis As A Discourse Method - Framing Climate Change Politics, Mat HopeCjLizasuainNo ratings yet

- Alva Noe Art As EnactionDocument5 pagesAlva Noe Art As Enactionr4wsh4rkNo ratings yet

- Technologies of Spectacle and 'The Birth of The Modern World'Document27 pagesTechnologies of Spectacle and 'The Birth of The Modern World'laurent lescop100% (1)

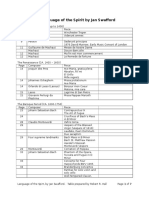

- Language of The Spirit Byjan Swafford, Recommended Music Pieces.Document7 pagesLanguage of The Spirit Byjan Swafford, Recommended Music Pieces.nantucketbobNo ratings yet

- Choreography As An Aesthetics of ChangeDocument36 pagesChoreography As An Aesthetics of ChangeMatthewDelNevo100% (1)

- World Happiness Report 2017Document188 pagesWorld Happiness Report 2017Luming LiNo ratings yet

- I Have Never Seen A SoundDocument6 pagesI Have Never Seen A SoundAna Cecilia MedinaNo ratings yet

- Stoic Fatalism, Determinism, and Acceptance - Stoicism and The Art of HappinessDocument8 pagesStoic Fatalism, Determinism, and Acceptance - Stoicism and The Art of HappinessjoiesdelhiverNo ratings yet

- Bachelard G - The Poetic of Space in HDM Reviewed by J OckmanDocument4 pagesBachelard G - The Poetic of Space in HDM Reviewed by J Ockmanleone53No ratings yet

- Memory, Imagination, and The Cognitive Value of The Arts: Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All Rights ReservedDocument14 pagesMemory, Imagination, and The Cognitive Value of The Arts: Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All Rights ReservedsuzannaNo ratings yet

- Statement On NeuroestheticsDocument2 pagesStatement On NeuroestheticsAvengingBrainNo ratings yet

- 7 Beacons of WritingDocument10 pages7 Beacons of WritingCluethun DerNo ratings yet

- Being Like Jesus and HitlerDocument17 pagesBeing Like Jesus and Hitlerjohnstone kennedyNo ratings yet

- Performing Feminisms, Histories, Rhetorics Author(s) - Susan C. Jarratt PDFDocument6 pagesPerforming Feminisms, Histories, Rhetorics Author(s) - Susan C. Jarratt PDFatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Film SylabiDocument5 pagesSociology of Film SylabiPalupi SabithaNo ratings yet

- Leppert Gestures TextDocument42 pagesLeppert Gestures TextNanda AndradeNo ratings yet

- Tracing The Other in The Theatre of The PrecariousDocument16 pagesTracing The Other in The Theatre of The PrecariousHospodar VibescuNo ratings yet

- Chaim PerelmanDocument9 pagesChaim PerelmanRejane AraujoNo ratings yet

- Humour As Art FormDocument9 pagesHumour As Art FormKapil SinghNo ratings yet

- ארכיטיפיםDocument71 pagesארכיטיפיםlev2468No ratings yet

- The Quest For Happiness in Self-Tracking Mobile TechnologyDocument145 pagesThe Quest For Happiness in Self-Tracking Mobile TechnologyAna RitaNo ratings yet

- Christina Bashford, Historiography and Invisible Musics Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century BritainDocument71 pagesChristina Bashford, Historiography and Invisible Musics Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century BritainVd0No ratings yet

- The Routledge Companion To Transmedia STDocument12 pagesThe Routledge Companion To Transmedia STZé MariaNo ratings yet

- Gallagher - "Hegel, Foucault, and Critical Hermeneutics PDFDocument24 pagesGallagher - "Hegel, Foucault, and Critical Hermeneutics PDFkairoticNo ratings yet

- The Nineteenth Century The Romantic PeriDocument87 pagesThe Nineteenth Century The Romantic PeriMahmut KayaaltiNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Affect and EmotionDocument7 pagesTheorizing Affect and EmotionRuxandra LupuNo ratings yet

- Creativity As A Sociocultural ActDocument16 pagesCreativity As A Sociocultural ActLou VreNo ratings yet

- The Objectivity of Taste Hume and Kant PDFDocument19 pagesThe Objectivity of Taste Hume and Kant PDFRicardo PickmanNo ratings yet

- TextureDocument4 pagesTextureapi-180230978No ratings yet

- Life Design-MadisonwittmayerDocument43 pagesLife Design-Madisonwittmayerapi-562153405No ratings yet

- Foucault Key ConceptDocument5 pagesFoucault Key Concept高夏怡No ratings yet

- Langer, SDocument3 pagesLanger, SgreggflaxmanNo ratings yet

- Arvidson-Askander-bruhn-fuhrer - Changing Borders. Contemporary Positions in IntermedialityDocument437 pagesArvidson-Askander-bruhn-fuhrer - Changing Borders. Contemporary Positions in IntermedialityMiguel Sáenz CardozaNo ratings yet

- Modelling The Structure of Binds and Double BindsDocument7 pagesModelling The Structure of Binds and Double Bindsthe_tieNo ratings yet

- Thinking No-One's Thought: Maaike BleekerDocument17 pagesThinking No-One's Thought: Maaike BleekerLeonardo MachadoNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Theatral PerformanceDocument19 pagesThe Analysis of Theatral PerformanceDaria GontaNo ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Route To A Composer's Subjectivity'Document13 pagesA Phenomenological Route To A Composer's Subjectivity'IggNo ratings yet

- Stories of Symphonic Music: A Guide to the Meaning of Important Symphonies, Overtures, and Tone-poems from Beethoven to the Present DayFrom EverandStories of Symphonic Music: A Guide to the Meaning of Important Symphonies, Overtures, and Tone-poems from Beethoven to the Present DayNo ratings yet

- Stanley N. Salthe-Development and Evolution - Complexity and Change in Biology-The MIT Press (1993)Document363 pagesStanley N. Salthe-Development and Evolution - Complexity and Change in Biology-The MIT Press (1993)JaimeNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Semiotics 0Document130 pagesCognitive Semiotics 0Gabriele FerriNo ratings yet

- Trauma and Memory in HousekeepingDocument3 pagesTrauma and Memory in HousekeepingspaceshipignitionNo ratings yet

- Catholic Religious OrderDocument4 pagesCatholic Religious Ordercontscribd11No ratings yet

- Space ConsiderationsDocument6 pagesSpace Considerationscontscribd11No ratings yet

- Review by William Caudill - Asylums Essays On The Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. by ErvingGoffmanDocument5 pagesReview by William Caudill - Asylums Essays On The Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. by ErvingGoffmancontscribd11No ratings yet

- Philip K. Bock - The Importance of Erving Goffman To Psychological AnthropologyDocument19 pagesPhilip K. Bock - The Importance of Erving Goffman To Psychological Anthropologycontscribd11No ratings yet

- Review by Randall Collins and Joel Aronoff - Relations in Public Microstudies of The Public Order by Erving Goffman Peter K. ManningDocument10 pagesReview by Randall Collins and Joel Aronoff - Relations in Public Microstudies of The Public Order by Erving Goffman Peter K. Manningcontscribd11No ratings yet

- Erving Goffman - The Neglected SituationDocument5 pagesErving Goffman - The Neglected Situationcontscribd11No ratings yet

- Frances Chaput Waksler and George Psathas - Selected Books and Articles About Erving Goffman and of Related InterestDocument6 pagesFrances Chaput Waksler and George Psathas - Selected Books and Articles About Erving Goffman and of Related Interestcontscribd11No ratings yet

- Clock Tree Design ConsiderationsDocument4 pagesClock Tree Design Considerationscontscribd11No ratings yet

- Anthony Giddens - On Rereading The Presentation of Self Some ReflectionsDocument7 pagesAnthony Giddens - On Rereading The Presentation of Self Some Reflectionscontscribd11No ratings yet

- JDBC and Database Programming in Java: Alexander Day ChaffeeDocument72 pagesJDBC and Database Programming in Java: Alexander Day Chaffeecontscribd11No ratings yet

- From Randal. in The Preface of The First Edition Of: Learning PerlDocument2 pagesFrom Randal. in The Preface of The First Edition Of: Learning Perlcontscribd11No ratings yet

- Proverbs 31:10-31 in A South African Context: A Bosadi (Womanhood) PerspectiveDocument43 pagesProverbs 31:10-31 in A South African Context: A Bosadi (Womanhood) PerspectiveChristopher SalimNo ratings yet

- TRAN 2018 Conceptual Structures VietnameseEmotionsDocument343 pagesTRAN 2018 Conceptual Structures VietnameseEmotionsRosío Molina-LanderosNo ratings yet

- Swales DiscoursecommunityDocument8 pagesSwales Discoursecommunityapi-242872902No ratings yet

- Valueclarificationpresentation 110717222953 Phpapp01Document15 pagesValueclarificationpresentation 110717222953 Phpapp01Josephine NomolasNo ratings yet

- 02-Serenity Tri-FoldDocument2 pages02-Serenity Tri-FoldWallace FirmoNo ratings yet

- Voegelins PlatoDocument33 pagesVoegelins PlatodidiodjNo ratings yet

- Dasgupta - Absolutism Vs Comparativism About QuantityDocument33 pagesDasgupta - Absolutism Vs Comparativism About QuantityGlen Canessa VicencioNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Sources HandoutDocument6 pagesEvaluating Sources HandoutSarah DeNo ratings yet

- Ideologies That Justify Political Vio - 2020 - Current Opinion in Behavioral SciDocument5 pagesIdeologies That Justify Political Vio - 2020 - Current Opinion in Behavioral SciMIANo ratings yet

- Fazlur Rahman's Influence On Contemporary Islamic PDFDocument26 pagesFazlur Rahman's Influence On Contemporary Islamic PDFisyfi nahdaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Philosophy of EducationDocument55 pagesWhat Is The Philosophy of EducationsoniaatyagiiNo ratings yet

- Marxist Approach To LawDocument10 pagesMarxist Approach To LawkushNo ratings yet

- (Guido Stein) Managing People and Organizations PDocument196 pages(Guido Stein) Managing People and Organizations PkailashdhirwaniNo ratings yet

- Experiencing Identity - I CraibDocument199 pagesExperiencing Identity - I CraibMichel HacheNo ratings yet

- Ilmu Pengetahuan Dari John Locke Ke Al-Attas: Izzatur Rusuli Dan Zakiul Fuady M. DaudDocument11 pagesIlmu Pengetahuan Dari John Locke Ke Al-Attas: Izzatur Rusuli Dan Zakiul Fuady M. DaudPutrioktalizaNo ratings yet

- Brief Overview of The Previous Assignment & How To Build ArgumentsDocument8 pagesBrief Overview of The Previous Assignment & How To Build ArgumentsZainal AthoNo ratings yet

- On Actor-Network Theory LatourDocument10 pagesOn Actor-Network Theory LatourfenixonlineNo ratings yet

- Political PhilosophyDocument43 pagesPolitical PhilosophyDr. Abdul Jabbar KhanNo ratings yet

- D NG 1: Agree or Disagree: For Your WritingDocument3 pagesD NG 1: Agree or Disagree: For Your WritingVy Đặng ThảoNo ratings yet

- Athens - Philosophical Challenges To The Sociology of ScienceDocument17 pagesAthens - Philosophical Challenges To The Sociology of ScienceNelida GentileNo ratings yet

- Argument Writing Graphic OrganizerDocument3 pagesArgument Writing Graphic Organizerapi-292725933No ratings yet

- The Rise of Informal Logic: Essays On Argumentation, Critical Thinking, Reasoning and Politics by Ralph JohnsonDocument269 pagesThe Rise of Informal Logic: Essays On Argumentation, Critical Thinking, Reasoning and Politics by Ralph JohnsonoriginalpositionNo ratings yet

- What Is ArtDocument36 pagesWhat Is Artyour mamaNo ratings yet

- 1LANG algMERGED PDFDocument12 pages1LANG algMERGED PDFjaveNo ratings yet

- HPS100H Exam NotesDocument16 pagesHPS100H Exam NotesJoe BobNo ratings yet

- Robert Moss - Dream Gates Chapter InformationDocument1 pageRobert Moss - Dream Gates Chapter InformationMihaela Poliana - PsihoterapeutNo ratings yet

- MODULE NA YELLOW PROFEd 104Document14 pagesMODULE NA YELLOW PROFEd 104Shiella mhay FaviNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Review of LiteratureDocument4 pagesFundamentals of Review of LiteratureJesah Christa MontañoNo ratings yet