Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Writing A Lab Report

Uploaded by

lsndrmrtnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing A Lab Report

Uploaded by

lsndrmrtnCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing a Lab Report

Overview

A good lab report does more than present data; it demonstrates the writer's comprehension of the

concepts behind the data. Merely recording the expected and observed results is not sufficient; you

should also identify how and why differences occurred, explain how they affected your experiment,

and show your understanding of the principles the experiment was designed to examine. Bear in mind

that a format, however helpful, cannot replace clear thinking and organized writing. You still need to

organize your ideas carefully and express them coherently.

Components of a laboratory report:

1. Title Page

- contains the name of the experiment, the names of lab partners, and the date. Titles should be

brief and concise yet informative (i.e. Not "Lab #4" but "Lab #4: Sample Analysis using the DebyeSherrer Method").

2. Abstract

- summarizes four essential aspects of the report: (a) the purpose of the experiment (sometimes

expressed as the purpose of the report), (b) key findings, (c) significance and (d) major

conclusions. The abstract often also includes a brief reference to theory or methodology. The

information should clearly enable readers to decide whether they need to read your whole report.

The abstract should be one paragraph of 100-200 words (the sample below is 191 words).

Sample Abstract

This experiment examined the effect of line orientation and arrowhead angle on a subject's

ability to perceive line length, thereby testing the Mller-Lyer illusion. The Mller-Lyer illusion is

the classic visual illustration of the effect of the surrounding on the perceived length of a line.

The test was to determine the point of subjective equality by having subjects adjust line

segments to equal the length of a standard line. Twenty-three subjects were tested in a

repeated measures design with four different arrowhead angles and four line orientations. Each

condition was tested in six randomized trials. The lines to be adjusted were tipped with outward

pointing arrows of varying degrees of pointedness, whereas the standard lines had inward

pointing arrows of the same degree. Results showed that line lengths were overestimated in all

cases. The size of error increased with decreasing arrowhead angles. For line orientation,

overestimation was greatest when the lines were horizontal. This last is contrary to our

expectations. Further, the two factors functioned independently in their effects on subjects'

point of subjective equality. These results have important implications for human factors design

applications such as graphical display interfaces.

3. Objectives

- Bulleted points. State the topic of your report clearly and concisely, in one or two sentences.

4. Materials (or Equipment)

- can usually be a simple list, but make sure it is accurate and complete. No need to put figures of

the equipment used.

5. Experimental Procedure

- describes the process in chronological order. Use flowchart for easier reference of the procedure.

Use past tense. Figures would help illustrate what was done.

- A good presentation of procedure would mean that another researcher should be able to

duplicate your experiment.

Beaker 1 was exposed

under sunlight for 30

Sample:

mins.

10 g of Sodium

Obtained 2 sets of 100

Bicarbonate was placed

ml of distilled water in

in each beaker

beaker

Beaker 2 was exposed

under moonlight for 3

years.

6. Data and Results

- usually dominated by calculations, tables and figures;

- Graphics need to be clear, easily read, and well labeled (e.g. Figure 1: Input Frequency and

Capacitor Value).

- In most cases, providing a sample calculation is sufficient in the report. You dont need to show all

computations.

7. Analysis and Discussion

- the most important part of your report, because here, you show that you understand the

experiment beyond the simple level of completing it.

- Explain. Analyse. Interpret. To substantiate this part, use both aspects of discussion:

a. Analysis

What do the results indicate clearly?

What have you found?

Explain what you know with certainty based

on your results and draw conclusions:

b. Interpretation

What is the significance of the results? What

ambiguities exist? What questions might we raise?

Find logical explanations for problems in the data:

Since none of the samples

reacted to the Silver foil test,

therefore sulfide, if present at all,

does not exceed a concentration

of approximately 0.025 g/l. It is

therefore unlikely that the water

main pipe break was the result

of sulfide-induced corrosion.

Although the water samples were

received on 14 August 2000, testing

could not be started until 10 September

2000. It is normally desirably to test as

quickly as possible after sampling in

order to avoid potential sample

contamination. The effect of the delay is

unknown.

- Compare expected results with those obtained. If there were differences, how can you account for

them? Saying "human error" implies you're incompetent. Be specific; for example, the instruments

could not measure precisely, the sample was not pure or was contaminated, or calculated values

did not take account of friction.

- Analyze experimental error. Was it avoidable? Was it a result of equipment? If an experiment

was within the tolerances, you can still account for the difference from the ideal. If the flaws result

from the experimental design explain how the design might be improved.

- Relate results to your experimental objective(s).

- Explain your results in terms of theoretical issues.

8. Conclusion

- can be very short in most undergraduate laboratories. Simply state what you know now for sure,

as a result of the lab:

Example: The Debye-Sherrer method identified the sample material as nickel due to the

measured crystal structure (fcc) and atomic radius (approximately 0.124nm).

- Notice that, after the material is identified in the example above, the writer provides a justification.

We know it is nickel because of its structure and size. This makes a sound and sufficient

conclusion.

- Generally, this is enough; however, the conclusion might also be a place to discuss weaknesses

of experimental design, what future work needs to be done to extend your conclusions, or what

the implications of your conclusion are.

9. References

- include your lab manual and any outside reading you have done.

- arrange alphabetically

Adapted from (with some personal adjustments):

http://www.ecf.utoronto.ca/~writing/handbook-lab.html

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Entrepreneurial Intentions of Cavite Business StudentsDocument12 pagesEntrepreneurial Intentions of Cavite Business StudentsKevin Pereña GuinsisanaNo ratings yet

- Key Personnel'S Affidavit of Commitment To Work On The ContractDocument14 pagesKey Personnel'S Affidavit of Commitment To Work On The ContractMica BisaresNo ratings yet

- PENGARUH CYBERBULLYING BODY SHAMING TERHADAP KEPERCAYAAN DIRIDocument15 pagesPENGARUH CYBERBULLYING BODY SHAMING TERHADAP KEPERCAYAAN DIRIRizky Hizrah WumuNo ratings yet

- Calculate Capacity of Room Air Conditioner: Room Detail Unit Electrical Appliances in The RoomDocument2 pagesCalculate Capacity of Room Air Conditioner: Room Detail Unit Electrical Appliances in The Roomzmei23No ratings yet

- All Paramedical CoursesDocument23 pagesAll Paramedical CoursesdeepikaNo ratings yet

- LEONI Dacar® 110 enDocument1 pageLEONI Dacar® 110 engshock65No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 and 5 - For StudentsDocument6 pagesChapter 4 and 5 - For Studentsdesada testNo ratings yet

- 797B Commissioning Guidebook 07 (Procesos)Document65 pages797B Commissioning Guidebook 07 (Procesos)wilmerNo ratings yet

- Optra - NubiraDocument37 pagesOptra - NubiraDaniel Castillo PeñaNo ratings yet

- SOF IEO Sample Paper Class 4Document2 pagesSOF IEO Sample Paper Class 4Rajesh RNo ratings yet

- CuegisDocument2 pagesCuegisTrishaNo ratings yet

- Raj Priya Civil Court Clerk FinalDocument1 pageRaj Priya Civil Court Clerk FinalRaj KamalNo ratings yet

- Vox Latina The Pronunciation of Classical LatinDocument145 pagesVox Latina The Pronunciation of Classical Latinyanmaes100% (4)

- M Audio bx10s Manuel Utilisateur en 27417Document8 pagesM Audio bx10s Manuel Utilisateur en 27417TokioNo ratings yet

- Epri ManualDocument62 pagesEpri Manualdrjonesg19585102No ratings yet

- Subtracting-Fractions-Unlike DenominatorsDocument2 pagesSubtracting-Fractions-Unlike Denominatorsapi-3953531900% (1)

- Base Is OkDocument84 pagesBase Is OkajaydevmalikNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management of VodafoneDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Management of VodafoneAnamika MisraNo ratings yet

- Airbus Reference Language AbbreviationsDocument66 pagesAirbus Reference Language Abbreviations862405No ratings yet

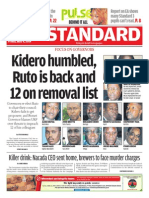

- The Standard 09.05.2014Document96 pagesThe Standard 09.05.2014Zachary Monroe100% (1)

- Arts and Culture An Introduction To The Humanities Combined Volume 4th Edition Benton Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesArts and Culture An Introduction To The Humanities Combined Volume 4th Edition Benton Test Bank Full Chapter PDFoutscoutumbellar.2e8na100% (15)

- Tensile TestDocument23 pagesTensile TestHazirah Achik67% (3)

- CHEMOREMEDIATIONDocument8 pagesCHEMOREMEDIATIONdeltababsNo ratings yet

- Cursos Link 2Document3 pagesCursos Link 2Diego Alves100% (7)

- Jt20 ManualDocument201 pagesJt20 Manualweider11No ratings yet

- Polygon shapes solve complex mechanical problemsDocument6 pagesPolygon shapes solve complex mechanical problemskristoffer_mosshedenNo ratings yet

- XDM-300 IMM ETSI B00 8.2.1-8.2.2 enDocument386 pagesXDM-300 IMM ETSI B00 8.2.1-8.2.2 enHipolitomvn100% (1)

- Inventory of Vacant Units in Elan Miracle Sector-84 GurgaonDocument2 pagesInventory of Vacant Units in Elan Miracle Sector-84 GurgaonBharat SadanaNo ratings yet

- TH255C Engine CAT PartsDocument134 pagesTH255C Engine CAT PartsKevine KhaledNo ratings yet

- Boat DesignDocument8 pagesBoat DesignporkovanNo ratings yet