Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ukraine - Test of The European Effectiveness

Uploaded by

Atelier_EuropeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ukraine - Test of The European Effectiveness

Uploaded by

Atelier_EuropeCopyright:

Available Formats

Atelier Europe

UKRAINE

TEST OF THE EUROPEAN EFFECTIVENESS?

Tatyana Augrand

Melody Defforge

Vera Lamprecht

Nino Pruidze

Augustin Roncin

Sciences Po.

Master Affaires Publiques

Master Affaires Europennes

Avril 2015

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

Abstract

LUkraine, test de lefficacit europenne ?

Ce qui tait un rve il y a un an est en train de se transformer en ralit, mme si ce

nest pas aussi vite que nous le voudrions. Nous avons retrouv la libert. Nous avons sign

laccord dassociation avec lUE 1 a dclar Petro Porochenko le 21 mai 2014. Ce jour-l,

lUkraine a commmor la Rvolution de la dignit commence un an plus tt par le

soulvement populaire suivant le refus de Victor Ianoukovitch de signer laccord dassociation

ngoci de longue date avec lUnion Europenne. Pour pro-europenne quelle soit, cette

rvolution nen a pas moins mis en lumire les dfis auxquels laction extrieure europenne est

confronte.

La crise ukrainienne actuelle sinsre dans le contexte des conflits gels survenus

depuis les annes 1990 au sein de lre post-Sovitique. Constitue dtats nouvellement

indpendants, la rgion est caractrise par des frontires politiques diffrant des frontires

ethniques et linguistiques historiques, et consquemment par lclatement de conflits

sparatistes soutenus par la Russie. limage de ces sparatismes, lEst de lUkraine a montr,

depuis lindpendance du pays, des tendances gopolitiques globalement diffrentes de celles

du reste des Ukrainiens. La volont russe de scuriser son tranger proche et de le maintenir

dans sa sphre dinfluence a donc pu sappuyer sur ces sparatismes afin de justifier sa prsence

dans ces rgions et son poids dans les ngociations internationales affrentes. Au sein de cet

environnement lUkraine se rvle emblmatique des dfis de lespace post-sovitiques. En

effet, eu gard lhritage sovitique, le pays est divis entre des minorits ethniques et

linguistiques la fois diffrentes et mles : si la minorit ethnique russe reprsente moins de

20% de la population, la majorit des ukrainiens sont bilingues. cela sajoute lentre difficile

de lconomie ukrainienne dans le capitalisme, marque par un impact ingal de par le pays

ainsi que la collusion entre hommes politiques et nouveaux oligarques. Ds 2004, la place

Madan a connu les rassemblements de la Rvolution Orange, rvlant les aspirations

dmocratiques de la population ukrainienne, sa volont de se rapprocher de lUnion Europenne

et mettant en lumire les rformes encore ncessaires.

Ds la fin des annes 1980, certains dirigeants europens ont appel une ouverture

diplomatique puis, la chute de lURSS, politique vers les pays dEurope de lEst jusqualors

maintenus sous la domination politique de Moscou. Le pouvoir normatif europen sy est ainsi

progressivement dploy travers la mthode de la conditionnalit attache aux diffrents

accords conclus avec lUE, tchant dinciter aux mesures de rforme, encourageant la

1 Guillemoles,

2014

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

dmocratie et lconomie de march. LUnion europenne dveloppa ainsi spcifiquement

lintention de son voisinage Est-europen le Partenariat Oriental, qui visait soutenir le

dveloppement conomique et la stabilit politique par le biais de son soft power. Mis en place

en 2009, le Partenariat prvoit un certain nombre de rformes suivant la Rvolution Orange.

Toutefois la Russie, percevant ngativement ce quelle considre comme une incursion de lUE

au sein de sa sphre dinfluence, ragit ce rapprochement par des guerres commerciales

successives parmi lesquelles la Guerre du gaz. LUkraine dpendant largement du commerce

avec la Russie, particulirement en matire nergtique, ces procds ont soulev de larges

proccupations parmi la population, et lUE sest alors implique dans la crise en tant que

mdiateur. Prise entre deux grandes puissances, les choix de lUkraine apparaissent ambigus,

hsitants, et le Prsident Ianoukovitch se tournera progressivement vers la Russie, sans pour

autant se dtourner tout fait de lUnion. Le Partenariat menace en outre de se fissurer sous le

poids de diffrentes dynamiques qui laniment. Se pose la question de laccession au statut de

membre des pays, car cest l la finalit initiale des accords dAssociation vers lesquels tendent

les partenaires. Les membres actuels apparaissent de plus diviss quant la conduite adopter

face lagressivit de la Russie.

La capacit de lUnion europenne trouver des rponses immdiates et unies aux dfis

auxquels elle est confronte dans son voisinage oriental et plus particulirement lors de la crise

rcente doit ainsi tre questionne. Aujourdhui les relations entre Kiev et Bruxelles sont

troites tandis que des ngociations sont en cours dans les domaines politiques, conomiques et

militaire. Face au soutien russe apport aux sparatistes qui combattent dans lEst de lUkraine,

lUnion a vot trois sries de sanctions conomiques contre le Kremlin et ses proches tandis que

les tats-membres continuent ngocier le rglement du conflit. Cependant la crdibilit et la

force de la politique trangre europenne ont t compromises par son action au sein de

lespace post-sovitique. En loignant des acteurs majeurs comme la Russie des ngociations, le

Partenariat oriental a effectivement branl la stabilit et la scurit des tats de la rgion. De

plus, les divergences croissantes au sein mme de lUE ont frein une action collective qui se

serait peut-tre montre plus mme de rsoudre les conflits. Lintrt national singre ainsi

dans les affaires europennes, les tats dpendant divers degrs des approvisionnements

gaziers russes. cela sajoute la complexit du conflit luvre dans lEst du pays et de

limplication russe, offrant des possibilits de rponse diplomatique et militaire limites.

Face ces difficults lUnion Europenne sest remise en question. La crise ukrainienne a

sans nul doute contribu relancer le projet dintgration par la voie nergtique grce au projet

dUnion de lnergie. Le dbat portant sur lopportunit dune arme europenne a en outre t

raviv, une telle force pouvant tre de nature faire de lUnion une puissance plus complte en

la dotant directement de mcanismes de hard power propres appuyer la volont politique de

stabilisation du voisinage europen. Considrant lhistoire de la coopration militaire sous gide

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

de lUE, il semble cependant plus probable qu court et moyen terme, les tats membres

continuent de sappuyer sur lOTAN pour assurer leur scurit collective. La politique trangre

de lUnion europenne tend tre renouvele tandis que se prpare le Sommet de Riga de mai

2015. Ainsi en mars dernier la haute reprsentante de lUnion pour les affaires trangres et la

politique de scurit, Federica Mogherini, ainsi que Johannes Hahn, commissaire charg de la

politique europenne de voisinage et des ngociations dlargissement, ont lanc une

consultation sur lavenir de la politique europenne de voisinage. Ses axes principaux visent

ainsi promouvoir une plus grande efficacit de la politique europenne en prenant acte des

difficults rencontres jusqualors : la prise en considration des voisins des voisins dans le

processus de dploiement normatif et politique, la lutte contre la corruption en faveur dune

mancipation de la socit civile ainsi que la mise en uvre de partenariats plus centrs sur les

spcificits inhrentes chaque tat.

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

UKRAINE

TEST OF THE EUROPEAN EFFECTIVENESS?

Ukraine has no history without Europe, but Europe also has no history without Ukraine.

Ukraine has no future without Europe, but Europe also has no future without Ukraine.

Throughout the centuries, the history of Ukraine has revealed the turning points in the history

of Europe. This seems still to be true today. Of course, the way things will turn still depends, at

least for a little while, on the Europeans. Timothy D. Snyder

Back in 2009, when the Eastern Partnership (EaP) was launched it was expected to

become a significant move forward and would project EU soft power into the post-Soviet space.

The EaP had notable positive outcomes on partner countries, including Ukraine, by promoting

its core values of rule of law, human rights, freedoms and democracy. Yet, lacking a clear

strategy with an ultimate objective, it was becoming obvious from the very beginning that the

EU initiative risked to become less efficient in time. There was a clear imbalance between the

interests of the EU on the one hand, which was focusing on stabilizing its neighborhood through

exporting European values, and EaP member states on the other, especially Ukraine, Georgia

and Moldova, which were showing high motivation in implementing needed reforms for deeper

integration with the Union. Five years later, with the events that broke out in December 2013 on

Maidan, these gaps in the policy were entirely unveiled. The 2013 Vilnius Summit was deemed

to be a major breakthrough due to the initialing of Association Agreements between the EU,

Georgia and Moldova. Yet the run-up to the summit was marred by Ukraine (along with

Armenia) rejecting similar agreements under Russian pressure, and in the end, the EaP came to

look like a policy in serious disarray.2

EUs interests in projecting its soft power beyond the borders lacked clarity as well as

financial resources directed towards the region. It also failed from the EUs perspective, as it

did not turn out to be a successful tool for the pursuit of milieu goals that is of indirectly

2 K.

L. Nielsen, M.Vilson, 2014. pp. 243262.

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

shaping the external environment by means of diplomacy and soft power.3 Five years later

Eastern Europe did not become more stable as a result of EU policy. This raised questions

among scholars as well as politicians. Some argued that the EaP played a part in destabilizing

the region by creating sufficient EU presence to provoke a Russian reaction (which always

perceived this region as its exclusive sphere of influence), but putting too little vigor in it to be

effective. Others continued to defend the position that the internal divisions of member states

over the further enlargement (or enlargement fatigue) required them to direct less focus on

enlargement issues.

However, the crisis in Ukraine served as a turning point and learning moment for the EU

to realize the urgency of updating its strategy to meet the existing challenges. The events in

Ukraine once again illustrated the importance of a stable neighbourhood, which was reflected in

the joint consultation paper recently published by the European Commission. In 2015, a decade

after the European Commission issued a first concept paper concerning the integration and

association of its future Eastern and Southern neighbours, the EU clearly admitted that it failed

to implement major ambitions of its policy. Thus, the importance of the change and adaptation

to the new environment created on EUs borders represents a lesson for the Union to rethink its

neighborhood policy, devise more effective instruments for its implementation, and most

importantly define ultimate objective of the strategy to ensure its effectiveness.

In this paper we have tried to show the extent of EUs capacity as a normative power

through analysing its efficiency in Ukraine pre and post Maidan. By placing the EU-Ukrainian

relations in historical context, we have demonstrated the important outcomes and challenges,

which existed or were formed in these relations. We have further assessed the role of EU in

coping with issues that arose, particularly with regards to Russia. Moreover, by demonstrating

the flaws of the Unions policies towards Ukraine, especially after Maidan, which became the

critical test of its efficiency, we have tried to show the questions that it unveiled and urgency of

change that it brought. Finally, we introduced the possibilities that the Ukrainian crisis created

for the European Union the necessity to rethink and reform its Eastern neighbourhood strategy

to make it more efficient and resilient.

Ibid.

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

I.

THE UKRAINIAN CRISIS

WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF

POST-SOVIET FROZEN

CONFLICTS (1991-2014)

A.

The birth of a new geopolitical space

1.

The birth of Post-Soviet nation states

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, fourteen newly independent republics emerged,

founded on the principle of uti possidetis. However, these entities were not constructed

according to clear ethnic and linguistic boundaries. In fact, citizens of these new republics have

been displaced, exiled4, and the Russian language represented a link throughout the whole

region, constructing national identity5, from Ukraine to Dagestan and Vladivostok.

Consequently, they included varied populations, representing religious, cultural and linguistic

diversity. As early as the 1990s, secessionist conflicts broke out in Azerbaijan (NagornoKarabakh), Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia) and Moldova (Transnistria) when national

minorities rose against central powers and claimed for independence. The eruption of these

conflicts was linked to historical, ethno-linguistic and geopolitical factors, and can not be

reduced to solely ethnic ones6. These conflicts remain unresolved until today. By means of

passportization policies or the deployment of peacekeeping forces, Russia managed to expand

its influence within the area and created so-called frozen conflicts. Another pattern that can be

observed in the post-soviet space during the 2000-2010 decade was the phenomenon of colour

revolutions, which followed elections denounced as fixed: Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004,

Kyrgyzstan in 2005, Belarus in 2006 and Moldova in 2009. Protesters used mostly non-violent

means to demand democratic reforms, which led to shifts in power and different levels of policy

changes.

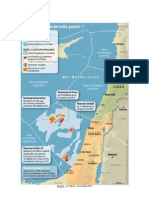

Arguably, the recent Ukrainian crisis bears the potential of creating new dynamics similar

to a frozen conflict. Through history, the western part of the country was influenced by Central

European kingdoms while the eastern one was closely integrated with Russia. As a result, the

country became increasingly divided in three areas, the western one being Ukrainian-speaking

and generally more likely to concur with so-called European values and the eastern part is

mostly Russian-speaking and with strong ties to Moscow. As a result, most of Ukraine is

bilingual. The clear separation between a Western and an Eastern Ukraine appears exagerated,

since the linguistic division proved to be more complex. Yet, figures showing that Crimea and

Donbass are largely Russian-speaking have to be linked to the fact that most of Russian4

Polian 2005.

Saparov 2003.

6 Parmentier 2015.

5

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

speaking medias in Ukraine are backed by Russian-owned companies, thus influencing public

opinion toward a pro-russian stance. Opinion polls illustrate that these internal political

division lines continue to exist. A survey conducted in 2008 showed that two-third of Southern

and Eastern Ukrainians did not believe their country would one day join the EU, while western

citizens were massively in favour7. A more recent poll highlighted the fact that half of the

surveyed in South and East are in favor of concluding a Customs Union with Russia, while in

the West three-quarter prefer to join the EU8. Similarly, while most of western Ukrainians are

convinced the country should join NATO, most of Eastern ones estimate it would not be a good

idea9. However, concerning the youth aged between 18 and 29, the aspiration to Europe appears

to vary very little between the East and the West10. This supports the idea that an important part

of Eastern Ukraine and Crimea showed different geopolitical yearnings during the last two

decades.

2.

Russias will to secure its near abroad

Russian Foreign Minister Andrey Kozyrev soon qualified the newly independent

republics as Russias near abroad11. These republics are under Russian influence for which

they represent a multifaceted asset. Their location on its southern and eastern borders makes it a

buffer zone impeding potential invasions. Moreover, Ukraine and Belarus are both among

Russias top five trading partners, while the Baltic states and Caucasus represent a way for

Russia to access warm waters. Moscow perceived successive EU and NATO enlargements as

encroachments of their interests, fearing that the promotion of Western states interests could be

detrimental to its own influence and power12. Thus, Russia is concerned that covert operations

could be conducted on its own territory or within its near abroad in order to undermine its

authority. This is why its government implemented measures to strengthen its NGOs

international financing regime following the Colour Revolution13. From the Cold War and the

NATO intervention in Yugoslavia, Moscow drew the conclusion that major foreign powers

violated international law which then limited Russian compliance to it. Russias answer

consisted of destabilizing interventions, such as in Georgia in 2008, which were then justified

by narratives of alleged American covert actions14. Russian governments have made use of local

conflicts to ensure their political predominance over governments in its sphere of vital interests.

Annie Daubenton 2014.

Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Litera 1994/1995, p. 45.

12 Wikileaks (online).

13 Baranovsky 2008, p. 45.

14 Bratersky, April-June 2014, p. 56.

8

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

This destabilizing action was achieved through support of separatist groups in various frozen

conflicts, from Moldavia to Ukraine. Trying to enhance its security, Russia takes advantage of

internal division to slow down the distancing of these countries and maintain them under its

control. Moscow could not have triggered these conflicts on its own and based its action on

existing separatists group15 whose independent existence could hardly be denied. The Kremlins

intervention consisted in providing economic, political, diplomatic and security support to these

groups, which would however, never have played such a role without Moscows support.

Given this context, the resurgence of the Eurasian Union project evidences the fact

Russia aims at establishing its own geopolitical project by exploiting its geographical location

which straddles two continents. As a consequence of its failure to integrate the western system,

Russia hopes to be at the centre of a new multilateral alliance with countries that are ready to

assume Moscows leadership. Putins government, more particularly, appears highly willing to

turn Russia into a Eurasian superpower. This shift became obvious during the 2006-2007 winter

when occurred a clear decrease of diplomatic contacts with western powers compensated by a

strong rise of contacts with Oriental countries16. The Economic Eurasian Union came into

effects in January 2015, bringing together Russia, Belarus, Armenia and Kazakhstan. This

Union aims toward integrating more countries and implementing a potential political and

military cooperation. It thus appears to compete with the EU on the integration of Eastern

Europe countries.

3.

The deployment of European normative power

The EUs orientation toward Eastern European dates back to the 1980s, when Margaret

Thatcher suggested the EC should open up to Eastern Europe17, remembering that the European

Community did not correspond to geographical and cultural Europe and making this point a

recurrent one in discourses concerning the construction of the European Political Cooperation.

In line with the approach of conditionality, in post-Soviet countries the EU tries to

provide incentives toward democracy and market economy. Therefore, concrete criteria have to

be met before economic and political agreements with the EU are concluded which provide for

further integration. Most importantly, the European Neighbourhood Policy launched in 2004

includes commercial agreements based on article 310 of the Treaty on European Communities,

also called Association Agreements (AA), meaning that the EU concludes commercial

agreements with Eastern European and Caucasus countries in return to which theses states must

launch comprehensive reforms. This policy of conditionality covers a broad range of fields

15

Parmentier, January 1st, 2007

Baranovsky 2008, p. 38.

17 Ibid.

16

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

concerned with the implementation of so-called European standards, such as democracy, good

governance, market economy and sustainable development. Further steps are to be implemented

if countries fulfil the conditions.

This method is supposed to promote the sharing of common political and economic

systems and thus the stabilization of Eastern Europe. In other words, Europe uses its normative

power to secure its milieu18. However, involved states do not systematically follow the agreed

conditions, manifesting or hiding difficulties to translate commitments into tangible policies, an

issue the EU failed to tackle properly19. This has to be linked to the fact that the conditionality

method suffers from ambiguity, since it can serve as an accelerator to adhesion or a simple

framework for close partnership. Indeed, it was initially developed as a method for integration,

but its use has evolved toward a soft-power tool to incite states to comply with European

political and economic standards and thus spread the European model20. Moreover this policy

can appear patronizing to involved states since the EU seems to have the upper hand on

negotiations. Finally, the EU external action proved unable to ensure the territorial integrity of

its partners and the intangibility of borders as evidenced by frozen conflicts becoming the status

quo. The EU progressively became more involved in the settlement of post-soviet frozen

conflicts due to its own institutional reform momentum, the development of the Common

Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and enlargements to the East21. The Union possesses a

special representative on Transnistria in Moldova since 2005. Yet, European action toward

frozen conflict is limited and has not produced dramatic effects so far. This could have been

caused by the lack of opportunity and willingness for member states to intervene, and could

possibly reveal the need for a more comprehensive European defence system.

B.

Ukraine, emblematic of Post-Soviet challenges

1.

Ethnic minorities

The premises of a growing tension between Ukrainian distinctive minorities were already

being obvious with the 1991 referendum. Indeed, the ethnic groups of the Ukrainian population

consisted of 77.8% of Ukrainians and 17.3% of Russians (2001)22, while other ethnic groups

also shared the Russian language as their native mother tongue. This distinctive feature reappeared in the forefront when Viktor Yanukovych in 2012, permitted the use of two official

languages in regions where the size of an ethnic minority exceeds 10%. This led to quarrels in

18

Nielsen/Vilsons 2014.

Balzacq 2007.

20 Korosteleva et al. 2014, p. 2.

21 Nielsen/Vilsons 2014.

22 Radvanyi 2011, p.76.

19

10

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

the Rada covered by the media23. The division line among languages became the watershed

between two different systems of values.

In order to obtain unity throughout the territory, Ukraine had to distance itself from the

imperial body it has previously been embedded in24. This would have required a great

involvment from the elite to deal with Ukraines bipolarity. Indeed, the country is rather

fragmented apart from the mere distinction of the language. In order to cope with this bipolarity,

and reinforce the sense of unity, several incentives were undertaken to gather people around

common values: such as the declaration by Viktor Yushchenko regarding the Holodomor

famine in 1932-1933, which was recognized as Ukrainian national tragedy25, and an entire

narrative was conveyed and supported in order to legitimize alienation with Russia. The

Holodomor famine episode is still very debated among historians26, yet it have been endured by

most of Ukrainians and if the figures may be contested, its existence is a fact. It is one of the

explanations for the very strong anti-soviet feeling that is simultaneously provoking hate against

soviet Union and against Russia, the latest manifestation being the memorial laws voted by the

actual Ukrainian Parliament, Douma, on April 9th 201527.

A few analysts have also pointed out that the fragmentation of the population would have

of a minor impact if the elite were not corrupt and if the were trusted. Indeed, Ukraine always

pursued a multi-vectored foreign policy, flexibly moving from the right to the left, from the East

to the West, regardless of who was in power argues H.J. Spanger28.

The recent uprising in Madan and the consequent independent movements that it created

highlights the impossibility to pursue the two-chair policy all former presidents tried to

implement in Ukraine29. After the failure of the elites who were expected to be loyal to peoples

aspirations expressed during the Orange revolution, the current dilemma at stake is to reinforce

Ukrainian national consciousness. That is possible through the empowerment of the civil

society Euromadan brought to light. One may emphasize the pluri-ethnic contributors to

Madan who embodied the national component that was previously missing to every political

unity: 21% of the protesters were from the East, the first one to call to protest was an Afghan

Ukrainian and the first to die an Armenian Ukrainian30. However, the structural and symbolic

maneuver at work in nation building needs to be supported by a positive economic context.

23

Le Monde, August 8th, 2012.

2014, p.80.

25 Ibid.

26 Werth 2007.

27 Vitkine, April 11, 2015.

28 Interview with Hans-Joachim Spanger, 2015.

29 Shevtsova 2014, p.80.

30 Guillemoles, February 19, 2015, p.29.

24Shevtsova,

11

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

2.

Economic liberalization and rule of law

The 2004 and the 2014 revolutions can be read as a total failure of transition to the

market economy in Ukraine31. The period was characterized by the lack of investments,

relatively slow increase of revenues, growing inequalities and cross-country high level of

corruption. An economic line of division adds to the cultural one : the West is more agricultural

and was consequently less exposed to fraudulent privatizations while the East is traditionally

more developed and wealthier thanks to its big, but uncompetitive industries. While Ukraine did

not follow the Russian path of the shock therapy (reforms started in 199432) the country did not

manage to build a strong domestic demand and was too dependent on the foreign, and more

especially Russian, demand for iron. Ukraine perspectives did not benefit from macro-economic

fundamentals to take-off (such as low inflation rate, confidence in the banking sector), which

led the GDP to decrease about 60% between 1989 and 1999. The 2000-decade witnessed an

improvement of the Ukrainian GDP though there was still a lack of structural reforms to endow

the economy with a long-lasting competitiveness. The system was dominated by oligarchs,

preventing institutional and small-scale investors to do business33. Furthermore, Ukraine did

not diversify enough its energy resources, putting its GDP in the hands of the Russian

government after the Kharkov agreement. Indeed the pact signed in 2010 offered Ukraine a

discount of 30% for the gas prices in exchange for the Russian lease of the Sevastopol fleet to

be extended to 204234. The 2014 revolution added a conjectural component that led to the

collapse of the GDP and the skyrocketing of the debt, to the point that no foreign loans managed

to aid.

Despite the ratification of the European Neighbouring Policy in 2004, Ukraine hardly

managed to meet the Rule of Law criteria, since it was suffering from weak economy and lack

of a reliable government. Ukraine first suffered from the collusion between L. Kuchma

(president between 1994 and 2005) and the oligarchs.35 The countrys aspiration to more

political transparency expressed during the Orange Revolution has been smashed to pieces by a

chaotic political arena during Yushchenko mandate. Indeed Ukraine had to face a political

instability illustrated by the modification of its constitution on December 8, 2004 in order to

give more power to the Parliament and weaken the presidential regime in favour of the

legislative body. Most importantly, during Ukraines recent years, political instability has been

the main reason behind the lack of any institutional and economic reform. The EU has been

practically non-effective to cure Ukraine from its ailment. A test for democracy will be the

31

Denysyuk, December 2014, 2014.

Radvanyi 2011, p.80.

33 Sutela, March 9, 2012.

34 Flikke et al. 2011.

35 Sutela, March 9, 2012.

32

12

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

Constitutional reform, Madan, and the recent Minsk II agreement. Ukraine will have to devise

its decentralization process in order to give more power to regions, and establish a genuine

democratic culture. Finally, Ukraine will have to cope with the local elections in October that

are of major importance to spread the transparency and the democratic energy demonstrated on

Madan.

3.

The Orange Revolution, foretaste of of Ukraines democratic endeavours

Intrinsic tension existing between Eastward/Westward-oriented people prevailed in the

political sphere and played an important role during the Orange revolution as well as for the

2004 presidency. Viktor Yanukovych, former Donetsk Governor, was first elected as president

in a controversial vote, being denounced by many NGOs. Soon after Viktor Yushchenko, the

former president of the Central Bank and former Kuchmas Prime Minister, invited people to

demonstrate embodying the first shout towards Europe coming from Ukraine. Ukraine not only

expressed its will to deepen ties with the European Union but also to witness necessary reforms

and foundations of the rule of law. After a compromise stemming from the willingness to

amend the constitution towards a more parliamentary-presidential system, V. Yushchenko was

elected as President in January 2005.

At that time, the EU managed to bring fast answers to the crisis. The EUs brokering role

has become active again after the breakup of the current crisis in Ukraine. Back in Yushchenko

years, the EU got involved with Moldova and Ukraine in the Border Assistance Mission

(EUBAM). If no formal adhesion has ever been put on the table, a proposition seemed within

reach. In 2007, both parties entered into negotiations that lasted over 6 years leading to the

Association Agreement. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that the EU missed the boat after

the Orange Revolution: it did not give Ukraine any prospect or clarity about the adhesion plan

while the country had been seeking for it not only in order to bring clarification but also to put

an end to Russian pressures.

II.

EASTERN PARTNERSHIP:

SOFT POWER AND ECONOMIC SUPPORT TO

COUNTRIES REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT (2004-2014)

A.

Establishing the framework of the Partnership

13

EASTERN

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

Launched in 2009, the Eastern Partnership meant to start on europeanisation beyond the

EU , joint initiative of the Polish and Swedish governments37, focusing on post soviet

36

countries, usually still very dependent on Russia. As a matter of fact, the partnership started at

the same time that Russia revealed a new role in the Neighbouring policy, starting a new

dialogue with the EU. Both dynamics had to maintain a very stable balance, yet the more

pressure Poland exerted in its relations with Russia, the more the EaP created issues that would

challenge its own existence, questioning the promises underlined and leading Ukrainian former

President Viktor Yanukovych to file it away for Russias offer: immediate economic inputs.

Countries such as Sweden and Poland promoted very strongly the Eastern part of the ENP,

placing their imprint in Europes collective foreign policy38.the Eastern Partnership aimed at

reinforcing the links between 6 former soviet countries: Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Armenia,

Azerbaijan and Belarus. The aims have been clearly identified as political association and

economic integration. The three key basis were: democracy and rule of law, respect for human

rights and commitment to market economy. The Democracy-promotion program39 from the

Eastern enlargement, started in 1999, had echoed as a promise for the Eastern Partnership

countries, even though EUs position was rather the opposite: if they met the criteria for

Europeanization, or the acquis communautaire (the body of European law), these countries

were expecting to be offered membership. Therefore, the majority of these countries and among

them Ukraine, was settled on such hope and expectation, however the EU repeatedly stated the

contrary.

1.

Post-Orange Revolution reforms

The Orange Revolution and Constitutional amendment gave birth to a new political

system in Ukraine: the economy opened investment to western businesses, and relations with

the EU and NATO became more substantial. The executive was split, since a lot of powers have

been transferred to the Prime Minister (at that time Yulya Tymoshenko). Internal quarrels

became a never-ending routine in the Parliament, consequently the reforms longed for never

happened. The economic recession impacted Ukraine even more harshly during this period; the

beginning political plurality and the dual form of executive power froze the needed reforms so

longed for. Subsequently, Yushchenko government lost total credit over the chaotic situation in

the country, and in 2006, Viktor Yanukovych became, once again, Prime Minister for one year.

36

Mller 2012.

Miltner 2010.

38 Mller 2012.

39 Meunier and McNamara 2007.

37

14

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

However, the Revolution sent a direct message to the EU and to the EaP, especially after

the 2008 Georgian conflict40.

The regional development programme from the EU has been perceived as a great

opportunity for Ukraine. However, the approach towards the Black Sea region evolved from

contractual bilateral relations to a more holistic package41. The delay and the economic

pressure forced President Yanukovych to ask Russia for help: the demand for a loan having

been rejected by the EU, Russia offered to cut gas prices and a 15 billion dollars loan on

December 17, 201342.

2.

The Russian response to western rapprochement: gas wars

Nevertheless the Ukrainian economy was strongly dependant on trade with Russia,

especially with regards to the very sensitive energy sector. The issue of gas supply became the

point break of the geopolitical struggle in the region. The Orange Revolution and the

subsequent political changes have posed to Russia great challenges with regards to its relation

with Ukraine. The Orange Revolution and the political change have been great challenges for

cooperation with Russia. Diminishing influence in one of the uppermost important partners of

the CIS was not an option. Therefore, the Kremlin started playing with gas prices in order to

orient the new Ukrainian government towards more flexibility. From 2006 until 2009, Gazprom

and Naftogaz managed to reach an agreement. At Viktor Yushchenkos request the EU43, which

was highly dependant on Russian energy flowing through Ukraine, engaged in a long process of

negotiations oriented towards solving the conflict through international mediation. The 2009

international gas conference failed. Yulia Tymoshenko and Vladimir Putin settled on a solution

after many hours of negotiations44. However, for the European countries this series of conflicts

over gas prices and supply significantly shaked Russias credibility as a reliable energy supplier

and also revealed Ukraines vulnerability to its neighbour.

Back in 2012, Viktor Yanukovych, with significant backing from Vladimir Putin, came

to power again. Yet the political dialogue with the EU and NATO did not come to an end. The

negotiations on the Association Agreement with the EU were initiated, and the EUs Foreign

Affairs Council remained hopeful to sign the initialled Association Agreement, including a

Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area, as soon as the Ukrainian authorities demonstrated

determined action and tangible progress in the three key basis of the EaP (democracy and rule

40 Englund

2014.

Homorozean 2011.

42 Kyivpost, December 17, 2013.

43 Interfax Ukraine, January 1, 2009.

44 BBC, January 19, 2009.

41

15

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

of law, respect for human rights and commitment to market economy), possibly by the time of

the Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius in November 201345.

3.

Yanukovychs return: Ukrainian hesitations

Initially relations between Ukraine, EU and NATO were deepening, although in an

uncertain way. Meanwhile relations with Russia were becoming more ambiguous. Like the

Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko, Viktor Yanukovych settled his game in a fragile

balance, aiming first of all at reaffirming his position in the political spectrum.

In fact, the situation was problematic: the 2008 global economic crisis importantly

weakened the Ukrainian economy, public debts were increasing and the country absolutely

needed support. The EU offered a package with many compromises: to free former Prime

Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, accepting IMFs proposition, a loan against the increasing gas

price, et alii Furthermore, the FTA with Europe was bringing to an end the possibility of

Ukraine joining the Eurasian Economic Union. And feelings towards Russia were at that time

still somewhat neutral, being a model for the Ukrainian country, which did not recover from the

fall of the USSR.

As a result, in november 2013 just before the Eastern Partnership summit in Vilnius,

Yanukovych abandoned the Association Agreement and instead opted for economic benefits

that were offered by Kremlin.

B.

First cracks in the Partnership

1.

Inter-EU division lines

The Ukrainian crisis raised doubts on the efficiency of EaP as a policy strategy,

demonstrated the lack and need of the ultimate objective of the program and underlined the

sharp disagreement of the EU member states on the Unions foreign policy. Clearly, for the EU

the Ukrainian crisis can be considered as the greatest test of its twenty-year old Common

Foreign and Security Policy, an area that has resisted integration more than any other. While in

spheres such as trade, regulation and monetary policy, the EU has forged increasing cohesion,

foreign policy still remains a platform for disunity.46

The first firm stance that the Union managed to take towards Russia as a response to its

annexation of Crimea was the round of sanctions of March 2014. However, the western

45

Council conclusions on Ukraine, 10 December 2012

Byrne, May 8, 2014.

46 A.

16

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

countries were late to react. Beyond the indecisiveness of the Member States lies a clear reason

such as the discrepancies existing between them on the EUs foreign policy and on its

relations with Russia. When Easter European governments took hawkish positions towards the

Kremlin since the very beginning of the crisis, the western countries remained more reserved.

The division lines of the Western European countries like Germany, France and the UK to agree

on the common position towards Russia resulted in their vested interest in the energy, defense

and financial sectors respectively. There was a serious lack on the part of EU to exercise

genuine power though, finally, the reserved member states started showing evident red lines

to Russia against its expansionist policy.

The governments in Berlin, Paris, and London managed to put their interests aside:

Germany, Europe's largest exporter to Russia (which also prior to the sanctions regime provided

the country with much of the high tech equipment used in its energy and extractive industries)

sacrificed a significant share of its export as a result of the embargo placed on the export of

these goods by the EU.47 France suspended the contract with Russia on the delivery of the

Mistral warship for which the payment had already been made. London unilaterally decided to

send about 75 soldiers to Ukraine to carry out tactical intelligence and some basic 'defensive'

infantry training there.

However, the Western countries, especially in the beginning of the crisis, demonstrated

naivety by blocking robust EU action towards Russia, hoping that Russian expansionism could

have been contained just by blacklisting people with direct links to the events in Ukraine. The

annexation of Crimea was not followed by the adequate response from the EU in order to oblige

the Kremlin to withdraw from the territories of a sovereign state. On the contrary, while the EU

member states had hard times in finding the common position for the first round of sanctions,

the Kremlin started the preparations for applying the traditional policy model of expansionism

through the pretext of protecting minorities in Eastern Ukraine. This highlights a fundamental

gap between the European and Russian means for action. The destabilization of bordering

territories with the aim of creating frozen conflicts has been a traditional strategy practiced by

Russian for years - the one used in Transnistria, Moldova and Georgia before August 2008

when Russia ultimately invaded two Georgian regions.

The differences between the Member States position were also highlighted by the

historical memory some EU member states had from their relations with Russia. The Eastern

European states, which still have a strong memory of Russian expansionist policy, have been

alarmed by the Russian actions since the beginning of the crisis. They have been calling for

NATO troops to be stationed in Baltic States and Poland to guarantee their security. Some

argued that NATO could claim that Russias invasion and annexation of Crimea in violation of

47 F.

Bermingham, August 26, 2014.

17

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

its international obligations and the 1994 Budapest Memorandum guaranteeing Ukraines

territorial integrity, could have been used as a justification giving right NATO member

countries to station troops (permanently) in eastern Europe. However, such measure does not at

this stage seem to be realistic in particular due to the opposition of France and Germany who

remain reluctant to breach 1997 NATORussia accords that pledged no additional permanent

stationing of substantial combat forces in this region.48 Yet Eastern European countries

succeeded to see the boosted naval presence in Baltic Sea along with a new network of

command centres, which NATO recently decided to set up in order to protect the region from

any potential threat. This move was the biggest reinforcement of the collective defense since the

end of the Cold War 25 years ago. NATO made clear that it would not intervene in Ukraine,

but would reinforce defences of alarmed eastern allies who were under Russian domination four

decades until 1989. The six command centers, which will be set up in Poland, Romania,

Bulgaria and the three Baltic States will plan exercises and provide support to these countries in

an emergency. 49

2.

Association promises vs. membership perspectives

The Ukrainian crisis reinforced the idea that policy strategies should be balanced (in

terms of requirements and rewards) in order to provide sufficient incentive and support,

especially since compliance costs are high. If we compare the 2004 enlargement policy with the

EaP, it becomes clear that the membership perspective was a much stronger incentive for the

countries to meet all the requirements in complying with EU standards. As Romano Prodi

recognized, when speaking of the CEEC candidates of the 1990s, by holding up the goal of

membership we enabled these governments to implement the necessary reforms50. If the

membership perspective strengthened the reformers in their efforts to overcome national

resistance, its absence would have played a serious role on the willingness and readiness of

these countries to implement [often] painful reforms. Hence, the rejection of President

Yanukovych to sign the Association Agreement, including the DCFTA, with the EU and instead

opting for a package of economic benefits which the Russian President offered as a reward for

that move, reinforces this idea.

The Eastern Partnership launched by the EU in May 2009 was definitely a significant

step to consolidate Europes zone of attraction but too embryonic. The EU has to diversify its

relations with the Eastern neighbors. Countries like Ukraine along with Georgia and Moldova

show much more interest towards the European project then the rest of the partnership

48 H.B.L.

Larsen, 2014. p. 38.

A. Croft, D. Alexander, 5, 2015.

50 Prodi, 2002.

49

18

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

members. In this normative and technocratic approach the EU made another crucial mistake in

failing to understand how Russia viewed Europe. Indeed the EUs normative external policy did

not integrate the need to take into consideration the Neighbours neighbourhood. This led to

Moscow reading the attempts of post-soviet states to deepen their ties with the Euro-Atlantic

organizations (EU, NATO) as largely conspiratorial. At minimum, in Kremlins mind these

activities have been aimed to drastically reduce Russias influence in its neighbourhood, at

worst, they have constituted a concealment to export European values and morals to Russia,

which could significantly shake the current regime. Thus, the thinking patterns of the West and

Russia are radically different. While the EU considers tensions and crisis in neighboring states

as a potential threat to the stability of liberal democracies, the Kremlin does its utmost to

destroy democratic regimes and create instability in order to have more room for tactical

maneuvering.51

The Ukrainian crisis clearly demonstrated the flaws of the Eastern Partnership program:

Firstly, the reluctance to irritate Russia, secondly the discrepancy between the interests of its

members (the program included 6 countries, which had little in common except the fact that all

of them were post-Soviet), and finally, the lack of the ultimate objective of the strategy. Many

in Europe believed that the Eastern Partnership would have served as a bridge between Russia

and Europe, although, the Kremlin itself erased these illusions with its actions in Ukraine.52

Therefore, a whole misunderstanding has been attached to the EaP concept. The EU failed at

convincing Eastern partners that EaP was no promise for further integration. Russia, on the

other hand, was strongly containing the EaP seeing it as a direct threat to its foreign policy,

especially when the program included Ukraine - a symbolic partner for Russia, who was seen as

a fundamental candidate for the Eurasian Economic Union.

3.

New opportunities for reviving the Partnership

The Ukrainian crisis seriously undermined the more for more policy, which the EU has

been pursuing in its Eastern Neighbourhood. Meeting the Copenhagen Criteria, which includes

strengthening democracy, rule of law, human rights among others, requires huge efforts from

the part of the EaP states. Therefore, the absence of the ultimate objective could only undermine

such policy. Hence, the EaP message was more than complex: calling for radical reforms,

democratization, human rights and economic stability but all this without giving a clear prospect

of accession to target countries.

51

52

L. Shevtsova, 2014.

Ibid.

19

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

The diplomats in Brussels seem to have finally embraced the idea that the EU must have

a more strategic approach to the politics of the Eastern neighborhood. Current commissioner for

the European neighborhood policy and enlargement negotiations, Johannes Hahn, pointed out

that the developments in EUs close vicinity directly impact Europes stability, security and

prosperity. Moreover, the commissioner acknowledged that the current policy was devised in

2004 and that Europe's neighborhood is now very different. Therefore, he demonstrated the

need of true tailor-made solutions rather than one-size-fits-all approach, especially

considering that each partner country has different challenges and levels of engagement.53 If

the member states do not significantly enhance the EUs foreign policy instruments,

reconstructing Ukraine or even keeping countries like Moldova and Georgia on their European

path will become difficult in the long run.54 The shift towards a more strategic approach would

definitely be a step forward for the EU.

The Ukrainian crisis has strengthened the idea that it is essential to demonstrate the

potential and the willingness to back up the promotion of European values and norms with

strategic actions. Thus, in the absence of improved foreign policy instruments in order to deal

with Russia and the post-Soviet space, it is doubtful that existing strategy can have any visible

impact on the ground. The review of the European Neighborhood Policy planned for May 2015

will be a good indicator to what extent the EU is willing to invest in creating new foreign policy

tools for dealing with its eastern neighbors.55

III.

QUESTIONING

THE

EUS

CAPACITY TO FIND IMMEDIATE AND UNITED RESPONSES

(2014-2015)

A.

EU-Ukraine relations since Maidan

1.

EUs assistance to Ukraine

On June 27th Ukraines newly elected President, Petro Poroshenko, signed the

association agreement (AA) along with the deep and comprehensive free trade area (DCFTA).

By doing so, Ukraine showed to the international community its firm standing towards

European integration, and took its revenge on the Russian vested interest to block its signature.

The Association agreement is the most advanced version of any agreement made by the

EU and commits Ukraine to economic, judicial, and financial reforms to converge its policies

53

J. O'Brien, February 20, 2015.

C. Nitoiu, March 3, 2015.

55 Ibid.

54

20

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

and legislation to those of the EU. The country will benefit from transitional periods to

gradually undertake all the necessary steps to transform and democratize its political and

economic sectors, though it does not seem to be enough for a country trying to defend itself

from the ongoing invasion of its territory by Russia, having deep economic recession and failed

institutions dominated by corruption.56 Furthermore, Russia managed to put pressure on Ukraine

to postpone the launch of the free trade area with Europe to the end of 2015.

The European Commission has agreed on a number of measures for the short and

medium term to help stabilizing the economic and financial situation in Ukraine, to assist with

the transitional period and to encourage political and economic reforms.57 In order to meet the

challenges presented by the situation in mid-2014, the Commission established the Support

Group for Ukraine. The Support Group coordinates the resources and expertise of the European

Commission in order to monitor and assist Ukraine in the implementation of the Association

Agreement and, crucially, in undertaking the necessary systemic reforms. Despite the fact that

this is the first time such a Support Group has been established for any country outside the

borders of the EU,58 unfortunately, few measures have been put in place to respond the crisis on

the short-run.

The European Unions executive is providing a significant financial assistance package to

Ukraine which is being supplemented to the significant assistance provided by the International

Monetary Fund (IMF). In the framework of the Macro Financial Assistance (MFA), which is a

crisis-response instrument available to the EUs neighbouring countries, the Commission in

January 2015 proposed an extra assistance of 1.8 billion to help Ukraine stave off bankruptcy.

The European executive already disbursed 1.36 billion under two previous MFA programs.

Thus, the EU became the biggest international donor to Ukraine. According to the Commission

in total the EU will provide at least 11 billion assistance from its budget and the EU based

international financial institutions (IFIs).

The financial support is definitely crucial for Kiev government to revive the economy and

save the country from bankruptcy though it is not enough to solve Ukraines other big problem,

which is $3 billion bond owed to Russia. A bizarre clause in the debt that matures in December,

states that if Ukraines debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 60%, Russia can demand early repayment of

the bond. That, in turn, would trigger a cross-default on a big mass of the governments other

debts. Currently Ukraine has already passed the 60% threshold; therefore, Russia holds the

leverage over Ukraines economy. 59

The challenges that Ukraine is currently facing can hardly be perceived as attainable for

56

Transparency International ranked Ukraine 142 (out of 175) in its annual corruption survey, while a 2012 study by

Ernst & Young placed Ukraine as one of the three most corrupt countries in the world.

57 European Commission Press Release Database (online), January 29, 2015.

58 Ibid.

59 The Economist, January 24, 2015.

21

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

any country. Kiev has to undertake fundamental structural reforms in the wide range of sectors

(which are Soviet-inherited under-performing structures), while fighting a hybrid war. It has

restrained itself from announcing a state of war, even when parts of its territory are occupied.

Instead the new government started conducting an anti-terrorist operation against Russiabacked militants.60

2.

Sanctions against Russia

The use of economic sanctions in international affairs is very delicate and can be

divided into two schools. Critics of sanctions argue that economic sanctions only legitimate an

aggressive behaviour from the local government, the sanctions being a proof of external

aggressivity. Moreover, the economic impact tends to lead to the implementation of mafia type

economic channels that will support the government. The pro sanctions stand is that they isolate

and quickens the end of a fragile and unbalanced government and economy. Furthermore, it

represents a strong political tool, symbolising disapproval of a given political action. In this

sense, the EU sanctions can be regarded as a rejection of the violation of the 1994 Budapest

Memorandum. Subsequently, sanctions can also be an intimidating instrument, identifying a

red line and potential further action. It has been said that EU and US sanctions put an end to

Russias annexation of Ukrainian territories61, letting its President know that his actions would

bring further consequences. In this viewpoint EUs sanctions can be considered as efficient, still

some other arguments have to be examined.

Different issues are at stake when using economic sanctions, and raises questions of

various types62. Firstly, whether sanctions are likely to reinforce and/or promote radicalization

of the current elite and population, depending on whether the sanctions are hitting too hard on

the countrys economy. This factor can be adjusted by using more or less comprehensive

sanctions. Since the 1990s, targeted economic sanctions became a standard as they are said to

produce a maximum effect on political key actors while sparing populations. The example of

Irak is quite relevant: critics pointed to many serious flaws, including the humanitarian

suffering of innocent civilians, the lack of clear criteria for lifting, and the failure of the

sanctions to put direct pressure on Iraq's leaders63. Passing sanctions is a political instrument,

but if the country cannot recover from the sanctions, then autocratic forces will be able to

achieve power by creating a rally around the flag effect among the population. Finally,

whether or not the sanctions are affecting third countries, including ones passing them. The

counter productivity of the sanctions will probably lead to abandon or simple inefficiency.

60

Sohn, February 10, 2015.

Guriev 2015.

62 Wallensteen 2004.

63 Global Policy Forum, August 6, 2002.

61

22

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

The first row of EU sanctions towards Russia was launched in March 17th, with level 1

sanctions64, imposing first travel bans and asset freezes against Russian and Ukrainian

officials65. On April 28th, the list is extended66 and on July 31, the third round of sanctions

targeted the financial sector (all majority government-owned Russian banks), trade restrictions

relating to the Russian energy and defence industries, and additional individuals and entities

designated under the EU asset freezing provisions.67

The EU targeted sanctions aimed at denouncing Crimeas annexion and deterring

Russias involvement in the Donbass war. However, the sudden increase in Vladimir Putins

popularity that went along with the 2013 Ukrainian crisis appears dangerous. The Levada

Center indicates that since November 2013 to March 2015, the approval rate of Vladimir Putin

rose from 61% to 86%. The Russian narrative has been fed by the sanctions, exaggerating a

so-called hatred of EU and the US toward Russia and its President. Considering such a public

support, it is very uneasy to Putins opponents to express a different position and many affairs68,

revealing negative actions from the governments part, didnt affect the rate of approval.

End of June, the EU members should decide whether or not new sanctions should be

engaged, the current sanctions expiring in July69. However, the EU appears persistently lacking

of unity since Germany has opposed sanctions from the very beginning70 and a few countries

are politically against them, even though there is no sign whether they will vote them or not:

64

European Union Newsroom.

Ibid.

66 International Trade Compliance Update 2014.

67 Council regulation 31 July 2014.

68 Euronews, March 9, 2015.

69 Croft/Pineau, March 19, 2015.

70 The Telegraph, April 24, 2015.

65

23

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

Greece, Hungary, Cyprus, Czech Republic and Italy71. These critics are more understandable

that they are linked to EU member States either economically intertwined with Russia or

politically opposed to EU policies.

The boomerang effect72 of the sanctions, the counter-sanctions imposed by the

Kremlin, arose many critics, especially if the sanctions aim at de-escalating the situation.

Sanctions policy should be applied in support of the EU foreign policy, clearly exposed to

international actors, and not being the strategy per se73 focusing on economic impact rather

than on russian policy changes. The balance between hard and soft power is also at stake, if EU

sanctions aim at being more politically and economically efficient.

3.

EUs negotiations with Russia

As opposed to the mediation led during the Orange Revolution, the different attempts of

the EU member states that took place in order to de-escalate the conflict did not show tangible

71

Russia Today, April 13, 2015.

Dolidze 2015.

73 Ibid.

72

24

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

progress so far. The only breakthrough that the EU had in negotiations with Russia was the

October 2014 Russia-Ukraine gas deal, when the European officials managed to broker an

agreement on the resumption of gas supplies to Ukraine over the winter. The agreement was

widely seen as the first glimmer of hope in easing tensions between the two parties.

According to the agreement the EU accepted the obligation to act as a guarantor for Ukraines

gas purchases from Russia and to help Kiev meet its outstanding debts.74 Yet, the Minsk I

ceasefire agreement of 5 September 2014, which was aiming to end five months of fighting in

the Eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk turned out to be a shaky deal. The agreement

brokered by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in Minsk, which

involved former Ukrainian president, leaders of the pro-Russian rebels, and a Russian delegate,

soon turned fragile, as the Kremlin did not cease its activities in Donbass region. The most

recent one Normandy Format, with Franco-German leadership, came at the time of intense

discussion that was taking place in the US on providing Ukraine with defensive lethal

assistance, and probably undermined any US decision to arm Ukraine. While EU Member

States themselves rule out the possibility of providing any lethal weapons to Ukraine and

remain focused on a diplomatic solution of the conflict.

The renegotiated agreement of February 11, 2015 under Franco-German leadership did

not meet the expectations of Ukraine. In particular, it failed to acknowledge the threat of

Russian requirements, which is the Kremlins insistence on federalization of Ukraine (while the

Ukrainian government advocates for decentralization). To many, federalization is understood as

dismemberment of Ukraine, which fits well in Russian interests to better control local

governments. The autonomy for Donbass marionette governments effectively means putting

Ukraines statehood at high risk. Examples of such model, which currently are entirely

controlled by Russia, are Georgian occupied regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Thus,

Ukrainians fear that Western diplomacy will result in a frozen conflict effectively creating a

Russian stronghold in Donbass and Crimea, which will ultimately impede Ukraines

development. 75

B.

A policy of missed opportunities?

1.

EUs limited margins of manoeuvre

At the latest since the Russian annexation of Crimea, the EU has been repeatedly

criticised for its timidity and timorousness vis--vis the crisis.76 Indeed, for a long period, the

74

BBC business, October 31, 2014.

Euobserver, February 10, 2015.

76 MacFarlane/Menon 2014, p. 95.

75

25

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

European reaction was strictly limited to public condemnations of the Russian aggression on the

one hand (fuelling the anti-western propaganda in Russia), and rhetoric support for proEuropean forces on the other hand. Both internal and external factors can be consulted for this

failure to find an effective and common European position. Firstly, it has already been shown

that the EUs foreign policy tools as provided for by the CSDP and within the ENP are not only

mostly soft in nature but also have a very limited scope.77 Due to this, European foreign policy

efforts have been materialized only through sanctions.78

Secondly, from the outset, energy questions limited the margins of manoeuvre of all

parties involved. Under Yanukovych, the experience of Russian energy blackmailing heavily

played into the initial non-signing of the AA in the run-up of Vilnius Summit in 2013. Ukraine

remains strongly vulnerable on Russian energy supply and can hardly oppose its pressure.

Admittedly, the EU can more easily oppose this pressure due to its economic importance.

Indeed, the May 2014 Energy Security Strategy issued in response to the Ukrainian crisis

provides for a larger degree of independence from Russia through diversification and enhanced

energy efficiency. Nonetheless, strong and long-lasting commercial and political ties between

Russia and several EU member states impede a more resolute approach towards Russia in the

energy sphere.

In a next step, with regard to consistent decision-making the EU is increasingly bound by

growing discrepancy between the positions of its member states and the transnational rise of far

right and far left parties. The EU-wide dissonance79 about the Ukrainian crisis which is

closely intertwined with the question of how to deal with an increasingly assertive, authoritarian

but strategically and economically still important Russia reveals a structural failure of the

European construction. Far from achieving a transnational European public sphere and

consciousness in the Habermasian sense, the EU remains divided on most fundamental

questions and consequently proves unable to unite in its external actions.

This is accurately illustrated by the Ukrainian case: even though there have been several

bi-, tri- or multilateral initiatives (i.e. the Normandy Format, the Weimar Triangle, Baltic

initiatives), the European Union member states remain deeply split along national boundaries.

France and especially Germany supported by changing coalitions, mostly from Central

European countries have clearly took the lead within the efforts for a conflict settlement.

Interestingly, despite their regional vulnerability to Russia, central European countries

failed to find a common stance towards the crisis. On the one hand Poland and the Baltic

countries are most fervently insisting on a tough European reaction80. By contrast, in the Czech

77

Cf. Witney et al. 2014, p. 2.

Cf. Nitoiu 2015.

79 Forbrig 2015, p. 1.

80 MacFarlnae/Menon 2014, p. 100.

78

26

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

Republic and Hungary vocal pro-Russian voices 81 continue to be raised. Countries such as

Italy and Spain are cautiously pondering their policies vis--vis Ukraine in order not to

exacerbate the improving relations with Russia.

The strengthening of far right and far left wing parties in European member states,

however, pose a serious challenge to responsible European policy-making. Indeed, the links that

can be established between both far right and left wing, mostly eurosceptic parties and the

Kremlin raise deep concerns about an increasing pro-Russian camp inside Europe.

Paradoxically, the new division lines generated by these forces follow a transnational logic, i.e.

by uniting behind parties such as Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy within the 8 th

European Parliament.

In this vein, the new Greek foreign minister of the radical-left Syriza party chose Moscow

as the symbolic destination for his first visit outside the EU. The Spanish left-wing party

Podemos similarly leans toward Russia. Both far left and far right French parties Front de

Gauche and Front National maintain very friendly relations with Putin, Front National recently

received a 9.4m loan from a bank with links to the Kremlin.82 The Hungarian President Orban

also maintains amicable links with Putin; the increasingly popular far right party Jobbik must

even be considered avowedly pro-Russian83. Similarly, politicians from three German parties

including the neo-Nazi National Democratic Party (NPD), the Eurosceptic Alternative for

Germany (AfD) and even the Social Democrats (SPD) are suspected to have received Russian

money.84 Even though this is a non-exhaustive list of the links between European populists and

the Russian government, it clearly demonstrates the dimensions of these ties, which are as part

of a broader Russian strategy, namely its hybrid warfare strongly undermining united

European efforts within the crisis.

2.

How to counter Russias hybrid warfare?

The term hybrid warfare, which was until recently only familiar to security experts, has

become the main classification for the multi-layered actions undertaken by Russia since the

beginning of 2014. According to the IISS Military Balance 2015, the term hybrid warfare

designates the use of military and non-military tools in an integrated campaign designed to

achieve surprise, seize the initiative and gain psychological as well as physical advantages

utilising diplomatic means; sophisticated and rapid information, electronic and cyber

operations; covert and occasionally overt military and intelligence action; and economic

81

Forbrig 2015, p. 4.

Paterson 2015.

83 The Economist, February 14, 2015.

84 Paterson 2015.

82

27

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

pressure85. In fact, as part of this, it has repeatedly been stated that Russia is winning the socalled information or propaganda war86. Especially with regard to the increasing activities of

Russian media outlets abroad (Russia Today; Sputnik, Russian language channels for Russian

minorities living abroad), the European Council summit of March 19/20, 2015 pointed to the

need to challenge Russia's ongoing disinformation campaigns87. Therefore, first steps are

already undertaken and to be finalised by June 2015. Thus, a dozen European public relations

and communications experts will be entrusted with refuting Russian voluntary misinformation

within the EU, i.e. for the Russian-speaking minorities in the Baltic countries.88 It is true that, in

conjunction with hard security assurances guaranteed by the NATO, this strategy could prove

effective against the Russian hybrid warfare. The NATO itself clearly recognizes that its current

deterrence strategy of a rapid military response is insufficient with regard to hybrid warfare. 89

Therefore, it advocates a more comprehensive approach, i.e. by involving the EU in an

institutional tandem. Karel Kovanda, former head of the Czech Delegation to NATO, also

states that the EU, rather than the military alliance might have appropriate tools for countering

hybrid warfare90.

Efforts to counter the Russian hybrid warfare clearly bear the risk of encouraging or even

contributing to the tightening up of the conflict that is sometimes already qualified a new Cold

war. Therefore, they shall be applied with prudent resolution, i.e. within the framework of

existing legislation and not by simply replicating Russian methods: with regard to the media

sector, the aim is clearly not to create a European propaganda, but to counter misinformation

by reporting truthfully. In this vein, an integrated EU-NATO effort seems a promising, or even

an opportunity not to be missed91.

3.

Controversies around European hard power

Within the Ukrainian crisis and particularly within the context of the Debaltseve debacle,

the issue of providing lethal weapons to Ukraine has reappeared, and with it the whole debate

about European security commitments. It has been truthfully argued that today, 25 years after

the end of the Cold War, the European Union is still unable to be the main security actor on the

European continent. Instead, the NATO, strongly shaped and still dominated by American

strategic concerns, remains the main guarantor of security. For instance, in response to the

Russian aggression in Ukraine, a 4,000 strong NATO rapid force has been set up in September

85

IISS 2015, p.5.

Euractiv 18/03/2015.

87 EUCO 11/15, p.5.

88 Euractiv 20/03/2015.

89 NATO Review Magazine 2014a.

90 NATO Review Magazine 2014b.

91 NATO Review Magazine 2014a.

86

28

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

201492. Reacting to the on-going and intensified fighting in Eastern Ukraine, in February 2015

NATO has agreed on another 5,000-strong spearhead force and the establishment of six new

bases in the Baltic Countries, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria.93

Despite these efforts of deterrence, claims concerning a solely European contribution are

constantly raised. Most recently, the European Union Commission President Jean-Claude

Juncker told the German newspaper Die Welt that a common European army would convey a

clear message to Russia, namely that the EU was serious about defending its European

values94. The underlying controversy revolves around the fundamental question whether the

European foreign policy will remain a normative power (an idea the ENP was obviously built

upon) or whether it should move towards being a hard power.

IV.

PERSPECTIVES

A.

The impact of the Ukrainian crisis on the EUs motivation to build the

European Energy Union

Though having tremendously weakened the role of the EUs external policy, the tragic

events in Ukraine may have created a significant positive effect on the sector of energy. Indeed,

the previous crisis in gas-supply (2006 and 2009), and the spectrum of a new one prompted the

EU to find solutions to insure energy security across its external borders. The Commission

made one of its top priorities to aim at more diversified sources in the next twenty-five years, a

goal recently revealed in the Commission Paper on the Energy Union Package (February 25,

2015). The paper addresses the overwhelmingly dependence the EU faces while importing 53%

of its energy every year95. It states that particular attention will be paid to upgrading the

Strategic Partnership on energy with Ukraine. 96. Not only this attention will focus on Ukraine

as a transitory country but also to enhance its gas network along with an appropriate

regulatory framework and an increasing energy efficiency . In response to the strong

dependence on Russia in terms of gas delivery, 80% of which transit through Ukraine (2009)97,

the EU started, though lately, to consider Ukraine as a major strategic energy pivot in the Black

Sea area. Indeed, between the EU and Russias spheres of influence in the region, the Black

Sea region has been considered by many as the arena on which Ukraine could make a visible

92

Morris 2014.

Marcus 2015.

94 Bazli et al, March 8, 2015.

95 European Commission, February 25, 2015, p.2.

96 European Commission, February 25, 2015, p.7.

97 Mankoff 2009.

93

29

Ukraine, test of the European effectiveness ?

and counting impact 98. Several plans have already addressed the issue on reverse flows from

Slovakia so as to reduce Ukraines dependency on Russia. However, with no less than five