Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scrutiny Explained

Uploaded by

Baber RahimCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scrutiny Explained

Uploaded by

Baber RahimCopyright:

Available Formats

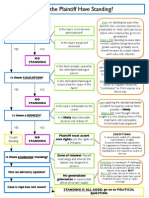

Challenging Laws: 3 Levels of Scrutiny Explained

By Brett Snider, Esq. on January 27, 2014 9:05 AM

When the constitutionality of a law is challenged, both state and federal courts will commonly apply

one of three levels of judicial scrutiny.

The level of scrutiny that's applied determines how a court will go about analyzing a law and its

effects. It also determines which party -- the challenger or the government -- has the burden of proof.

Although these tests aren't exactly set in stone, here is the basic framework for the most common

levels of scrutiny applied to challenged laws:

Strict Scrutiny

This is the highest level of scrutiny applied by courts to government actions or laws.

The U.S. Supreme Court has determined that legislation or government actions which discriminate on

the basis of race, national origin, religion, and alienage must pass this level of scrutiny to survive a

challenge that the policy violates constitutional equal protection.

This high level of scrutiny is also applied whenever a "fundamental right" is being threatened by a law,

like the right to marriage.

Strict scrutiny requires the government to prove that:

There is a compelling state interest behind the challenged policy, and

The law or regulation is narrowly tailored to achieve its result.

Intermediate Scrutiny

The next level of judicial focus on challenged laws is less demanding than strict scrutiny. In order for a

law to pass intermediate scrutiny, it must:

Serve an important government objective, and

Be substantially related to achieving the objective.

This test was first accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1976 to be used whenever a law

discriminates based on gender or sex. Some federal appellate courts and state supreme courts have

also applied this level of scrutiny to cases involving sexual orientation.

As with strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny also places the burden of proof on the government.

Rational Basis Review

This is the lowest level of scrutiny applied to challenged laws, and it has historically required very

little for a law to pass as constitutional.

Under the rational basis test, the person challenging the law (not the government) must prove either:

The government has no legitimate interest in the law or policy; or

There is no reasonable, rational link between that interest and the challenged law.

Courts using this test are highly deferential to the government and will often deem a law to have a

rational basis as long as that law had any conceivable, rational basis --even if the government never

provided one. This test typically applies to all laws or regulations which are challenged as irrational or

arbitrary as well as discrimination based on age, disability, wealth, or felony status.

These levels of scrutiny can and will continue to change as courts apply them in the future.

You might also like

- State Action and Equal Protection Judicial ReviewDocument24 pagesState Action and Equal Protection Judicial ReviewNate Enzo100% (1)

- Con Law II OutlineDocument29 pagesCon Law II OutlineLangdon SouthworthNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law OutlineDocument16 pagesConstitutional Law OutlineStephanieIjomaNo ratings yet

- Con Law II Outline PKDocument106 pagesCon Law II Outline PKSasha DadanNo ratings yet

- State ActionsDocument1 pageState ActionsKatie Lee WrightNo ratings yet

- Due Process and Equal Protection Analysis OutlineDocument43 pagesDue Process and Equal Protection Analysis Outlineawreath0% (1)

- Con Law Equal Protection 2009Document56 pagesCon Law Equal Protection 2009The LawbraryNo ratings yet

- Con Law PracticeDocument10 pagesCon Law PracticeNick ArensteinNo ratings yet

- Con Law Outline For 1 and 2 Good OutlineDocument35 pagesCon Law Outline For 1 and 2 Good Outlinetyler505No ratings yet

- I. Judicial Review: Master Constitutional Law Outline Professor BurrisDocument74 pagesI. Judicial Review: Master Constitutional Law Outline Professor BurrisDavid YergeeNo ratings yet

- Con Law II Notes & CasesDocument71 pagesCon Law II Notes & CasesKunal Patel100% (1)

- Con Law Issue ChecklistDocument1 pageCon Law Issue ChecklistAtticus FinchNo ratings yet

- Con Law OutlineDocument22 pagesCon Law OutlineslavichorseNo ratings yet

- Con Question OutlineDocument5 pagesCon Question OutlineKeiara PatherNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Defenses and ElementsDocument19 pagesCriminal Law Defenses and ElementsSonora VanderbergNo ratings yet

- Con Law II NotesDocument190 pagesCon Law II NotesBNo ratings yet

- EPC, DPC Attack PlansDocument6 pagesEPC, DPC Attack PlansEl100% (3)

- Administrative Law Substantive OutlineDocument29 pagesAdministrative Law Substantive OutlineMatt StiglbauerNo ratings yet

- Con Law II OutlineDocument49 pagesCon Law II OutlineAdam Warren100% (1)

- Civil Procedure Outline (Detailed)Document91 pagesCivil Procedure Outline (Detailed)par halNo ratings yet

- Scrutiny Categorization Chart PDFDocument1 pageScrutiny Categorization Chart PDFBrady WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Con Law Short OutlineDocument17 pagesCon Law Short OutlineJennifer IsaacsNo ratings yet

- Conlaw Rights Outline - CODY HOCKDocument49 pagesConlaw Rights Outline - CODY HOCKNoah Jacoby LewisNo ratings yet

- Con Law OutlineDocument21 pagesCon Law OutlineYan Fu0% (1)

- Con Law II OutlineDocument59 pagesCon Law II OutlineHenry ManNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection Flow ChartDocument1 pageEqual Protection Flow ChartLaurie Smith100% (2)

- Religion in Schools: Key Supreme Court Cases on Prayer and CreationismDocument22 pagesReligion in Schools: Key Supreme Court Cases on Prayer and CreationismDoyon WonNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law I Outline 2013Document29 pagesConstitutional Law I Outline 2013The Lotus Eater100% (2)

- Business Organizations OutlineDocument29 pagesBusiness Organizations OutlineMissy Meyer100% (1)

- Legal Professions OutlineDocument40 pagesLegal Professions Outlinechristensen_a_gNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Outline - 1LDocument4 pagesCivil Procedure Outline - 1LEben TessariNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law OutlineDocument21 pagesAdministrative Law Outlinemflax09100% (1)

- Devlin Con Law I 2011 - Quick Sheets For ExamDocument5 pagesDevlin Con Law I 2011 - Quick Sheets For ExamJeremy100% (1)

- The Mother of All Civ Pro OutlinesDocument103 pagesThe Mother of All Civ Pro Outlinessuperxl2009No ratings yet

- Tiff's Crim Law OutlineDocument37 pagesTiff's Crim Law Outlineuncarolinablu21No ratings yet

- Con Law IIDocument48 pagesCon Law IIKatie TylerNo ratings yet

- Speech Chart of CasesDocument10 pagesSpeech Chart of CasesusflawstudentNo ratings yet

- Con Law SkeletalDocument20 pagesCon Law Skeletalnatashan1985No ratings yet

- Con Law Cheat Sheet (Judicial Tests)Document4 pagesCon Law Cheat Sheet (Judicial Tests)Rachel CraneNo ratings yet

- Con Law II - Final OutlineDocument27 pagesCon Law II - Final OutlineKeiara Pather100% (1)

- Levels of Constitutional ScrutinyDocument22 pagesLevels of Constitutional ScrutinyFarah RahgozarNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law ChecklistDocument1 pageConstitutional Law ChecklistJ WattsNo ratings yet

- Employment Exam ChecklistDocument13 pagesEmployment Exam ChecklistseabreezeNo ratings yet

- Bartlett - Contracts Attack OutlineDocument4 pagesBartlett - Contracts Attack OutlinefgsdfNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro ChartsDocument3 pagesCrim Pro ChartsJane Hazel GuiribaNo ratings yet

- PR OutlineDocument34 pagesPR OutlineroseyboppNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law OutlineDocument86 pagesConstitutional Law OutlineEvanKing100% (2)

- CrimPro FlowChartDocument2 pagesCrimPro FlowChartslowdough2003No ratings yet

- CrimPro FlowChart 1Document3 pagesCrimPro FlowChart 1jumbojetjet50% (2)

- MPC Accomplice Liability and Common Law Conspiracy ComparedDocument12 pagesMPC Accomplice Liability and Common Law Conspiracy ComparedRick Coyle100% (1)

- Crim Exam OutlineDocument29 pagesCrim Exam OutlineSunny Reid WarrenNo ratings yet

- Commerce Clause Cases ExplainedDocument1 pageCommerce Clause Cases ExplainedkillerokapiNo ratings yet

- Business OrganizationsDocument71 pagesBusiness Organizationsjdadas100% (2)

- Labor Law Outline - TBDocument141 pagesLabor Law Outline - TBThomas Oglesby67% (3)

- Constitutional Law Free Speech OutlineDocument2 pagesConstitutional Law Free Speech OutlineEl0% (1)

- Standard of Review Levels of ScrutinyDocument2 pagesStandard of Review Levels of ScrutinyE.F.FNo ratings yet

- Strict Scrutiny' Test in Constitutional Adjudication: Indian ExperienceDocument22 pagesStrict Scrutiny' Test in Constitutional Adjudication: Indian ExperienceChiranjeev RoutrayNo ratings yet

- Miriam Defensor-Santiago's Three Standards of Judicial ReviewDocument1 pageMiriam Defensor-Santiago's Three Standards of Judicial ReviewAnonymous 5MiN6I78I00% (1)

- State Interest: A Broad Term For Any Matter of Public Concern That Is Addressed by A Government in Law or PolicyDocument1 pageState Interest: A Broad Term For Any Matter of Public Concern That Is Addressed by A Government in Law or PolicyYnel MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Case Law and Criminal Procedure AndreaGonczolDocument12 pagesCase Law and Criminal Procedure AndreaGonczolEleonóra KopilovicNo ratings yet

- Class Note 1 IntroductionDocument17 pagesClass Note 1 IntroductionBaber RahimNo ratings yet

- Factum TemplateDocument6 pagesFactum TemplateBaber RahimNo ratings yet

- Con-Law Rosenberg f04 2Document23 pagesCon-Law Rosenberg f04 2Baber RahimNo ratings yet

- Conlaw Shortol ChillDocument2 pagesConlaw Shortol ChillBaber RahimNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection FlowChartDocument1 pageEqual Protection FlowChartBaber Rahim100% (1)

- Torts Rules of Law (Simplified)Document4 pagesTorts Rules of Law (Simplified)Baber RahimNo ratings yet

- Torts OutlineDocument74 pagesTorts OutlineBaber Rahim0% (1)

- Conlaw OpeningpsDocument4 pagesConlaw OpeningpsKaran MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Torts Rules of Law (Simplified)Document4 pagesTorts Rules of Law (Simplified)Baber RahimNo ratings yet

- Torts OutlineDocument74 pagesTorts OutlineBaber Rahim0% (1)

- Equal Protection FlowChartDocument1 pageEqual Protection FlowChartBaber Rahim100% (1)

- Constitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4Document1 pageConstitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4amberpenn70% (10)

- Constitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4Document1 pageConstitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4amberpenn70% (10)

- Con Law FlowchartsDocument11 pagesCon Law Flowchartstdickson1597% (74)

- Con Law Flow Chart EPC DPCDocument2 pagesCon Law Flow Chart EPC DPCBaber Rahim100% (1)

- Constitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4Document1 pageConstitutional Law Commerce Clause Flowchart4amberpenn70% (10)

- Con Law - Spring 2015 OutlineDocument58 pagesCon Law - Spring 2015 OutlineBaber RahimNo ratings yet

- Con Law ChartsDocument5 pagesCon Law ChartsBaber Rahim100% (2)

- Torts Liability for Wrongs InflictedDocument75 pagesTorts Liability for Wrongs InflictedBaber RahimNo ratings yet

- Henry Highland GarnetDocument11 pagesHenry Highland GarnetNasserElhawyNo ratings yet

- Petitioners - TC 21Document34 pagesPetitioners - TC 21Jinal SanghviNo ratings yet

- Gans (1979) Symbolic EthnicityDocument21 pagesGans (1979) Symbolic EthnicityLefteris MakedonasNo ratings yet

- Historic Devices, Badges, and War-Cries by B. Palliser (1870)Document451 pagesHistoric Devices, Badges, and War-Cries by B. Palliser (1870)Andres MäevereNo ratings yet

- Summary of Sabrimala JudgmentDocument3 pagesSummary of Sabrimala JudgmentRadheyNo ratings yet

- Indian Judiciary ReportDocument18 pagesIndian Judiciary ReportLö Räine AñascoNo ratings yet

- L.E.T. Review Bped (P.E. & Health) Team SportsDocument8 pagesL.E.T. Review Bped (P.E. & Health) Team SportsEmelrose LL MacedaNo ratings yet

- GEC 2223 Rizals Life and Works FINALS REVIEWERDocument14 pagesGEC 2223 Rizals Life and Works FINALS REVIEWERitsmeglennieeNo ratings yet

- Victorian Women's Education and Role According to Sarah EllisDocument4 pagesVictorian Women's Education and Role According to Sarah EllisDemiieZuuNo ratings yet

- Mandatory To Serve Plaint and Documents With SummonsDocument3 pagesMandatory To Serve Plaint and Documents With SummonsSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್0% (1)

- Gravitt v. Smith Et Al - Document No. 3Document2 pagesGravitt v. Smith Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Layout 2 PDFDocument4 pagesLayout 2 PDFEMA UBAID ANDONANo ratings yet

- Vision of Charles XI foretells Sweden's futureDocument6 pagesVision of Charles XI foretells Sweden's futureshivraj360No ratings yet

- Quick Guide To PAB BudgetDocument1 pageQuick Guide To PAB BudgetNews 8 WROCNo ratings yet

- Placer Vs VillanuevaDocument7 pagesPlacer Vs VillanuevaKarina Katerin BertesNo ratings yet

- Kaunda: Mulungushi Conference AND A Guide TO THEDocument68 pagesKaunda: Mulungushi Conference AND A Guide TO THEDon-bee KapsNo ratings yet

- 08 MERALCO v. Jan Carlo GalaDocument2 pages08 MERALCO v. Jan Carlo GalaPaolo Miguel ArqueroNo ratings yet

- RTC and SC rule on real estate sale contractDocument2 pagesRTC and SC rule on real estate sale contractCharlie BartolomeNo ratings yet

- 6.heirs of Polcronio Ureta Vs Heirs of Liberato Ureta September 14 2011 GR No 165748Document37 pages6.heirs of Polcronio Ureta Vs Heirs of Liberato Ureta September 14 2011 GR No 165748Emmylou Ferrando BagaresNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH B - EssayDocument18 pagesENGLISH B - EssayCarolina Zavala CázaresNo ratings yet

- Congress Rule (1937-1939)Document7 pagesCongress Rule (1937-1939)daud.agha2010No ratings yet

- Teofilo Yldefonso MonologueDocument3 pagesTeofilo Yldefonso MonologueJicoy Viloria TarucNo ratings yet

- Milgram, Zimbardo, Asch experimentsDocument4 pagesMilgram, Zimbardo, Asch experimentsKonstantin Ruzhnikov100% (3)

- LA Law 5x01 - The Bitch Is BackDocument57 pagesLA Law 5x01 - The Bitch Is Backkinghall2891No ratings yet

- Duties and Rights of Innkeepers Under Common LawDocument11 pagesDuties and Rights of Innkeepers Under Common Lawmohd izzat amsyat0% (1)

- Epic of BantuganDocument4 pagesEpic of BantuganLalaine Jade0% (1)

- 37 Carandang vs. Heirs of Quirino A. de GuzmanDocument28 pages37 Carandang vs. Heirs of Quirino A. de Guzmanericjoe bumagatNo ratings yet

- Trust Receipts Case DigestsDocument15 pagesTrust Receipts Case DigestsGio TriesteNo ratings yet

- Protecting The Rights Of: Stateless PersonsDocument20 pagesProtecting The Rights Of: Stateless PersonsShai F Velasquez-NogoyNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Baptist ConventionDocument3 pagesMyanmar Baptist Conventiongooch556No ratings yet