Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Outsourcing Manifold Production

Uploaded by

alirazaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Outsourcing Manifold Production

Uploaded by

alirazaCopyright:

Available Formats

Perry & Paul, LLP

To:

Date:

Mike Lewis, Plant Manager

June 4, 1990

From:

Subject:

Ronald Perry, Senior Partner

Outsourcing of manifolds

I.

Introduction

It has been about two weeks since we discussed the possibility of outsourcing the production of manifolds at the

Automotive Component & Fabrication Plant (ACF). My office has since exerted great effort in our investigation of the

ACFs concerns, as it is our mission to reach the strategic decision that will best help our clients in achieving future goals.

We have carried out the procedures necessary for gaining an understanding of the ACFs cost system, as well as any

additional matters that may affect the facilitys production costs. I present you with the results of our investigation and, as

a conclusion, offer you my recommendation as to whether the ACF should outsource its production of manifolds.

II.

Investigation & Analysis

i. Background and Key Issues

In order to decide upon a suitable strategy for the ACF, we began by reviewing the companys recent historyin

particular, the circumstances that have led to the facilitys current state of uncertainty. Firstly, it is important to note that

the ACF is a key manufacturer of components for leading automobile producers in the U.S. The ACFs competition,

which once was limited to domestic suppliers, has rapidly increased since 1985, as a major paradigm shift is taking place

within the industry. In particular, rising gasoline prices and higher foreign competition have led to significant losses of

market share for the domestic automobile sector. As a result, the ACF and its competitors must vie for a smaller number

of production contracts, thereby reducing the facilitys sales volume. The dynamics of the automobile industry have been

particularly volatile for the ACF in the previous few years, as the facility was forced to close down several of its plants.

To combat the trend of decreased market share, the ACF devised a plan several years ago that involved analyzing

their product lines and outsourcing those that fell significantly below the world-class standard. As a result, the facility

recently outsourced its production of mufflers and oil pans, while also making labor improvements in an effort to match

the world-class production efficiency of its foreign competition. Despite these efforts, the ACF continues to fall behind

its competition and lose market share to foreign competitors. Currently, the ACF must decide whether to outsource its line

of manifolds, which have recently received a major downgrade in classification. Yet the prospect of increased emission

standards, which would drive up the demand and price for the ACFs manifolds, has compelled the facility reach a

decision more cautiously, as a premature disposal of the product line may result in a forgoing of higher sales and profit.

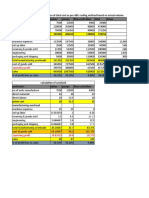

ii. Allocation of Manufacturing Overhead at the ACF

During my analysis of the ACFs cost system, I discovered that the plant relies on a single cost driverthe cost of direct

laborto allocate its overhead to products. Knowing this, I was able to calculate the plants budgeted overhead allocation

rate (Exhibit 1) for the past four years. There was a minor overhead variance in 1987, when the ACF had an overapplied

overhead: the actual overhead rate was 435%, while the predetermined rate, which was used to calculate the plants

applied overhead, was 437%. The variance reflects that the cost of direct hours was too high to apply overhead correctly;

however, the small difference between the two rates is typical for a system that relies on estimates.

Between 1987 and 1988, the ACF did not experience any major changes in its budgeted direct labor and overhead;

as a result, the shift in the overhead rate between those years was relatively insignificant. However, in stark contrast, the

overhead rate rose by almost one third between 1988 and 1989. These changes are mainly attributed to the facilitys

decision to outsource oil pans and mufflers, as sixty direct labor jobs and thirty indirect labor jobs were lost in the process.

Given that the overhead allocation rate is driven by the cost of direct labor, the loss of these jobs directly impacted the

overhead allocation rate. Furthermore, although budgeted sales fell by nearly forty percent with the decrease in

production, the facilitys overhead costs did not decline at the same degree, falling by almost 30 percent. This

discrepancy likely resulted because of the overhead accounts inclusion of fixed costs, which remain relatively constant at

expected levels of production activity. Yet since the ACF was functioning below its typical range of activityas

Perry & Paul, LLP

exemplified by its reduction of indirect laborcosts that once were considered fixed likely declined as well, although not

as sharply as the variable costs that fell directly with the decrease in production.

Between 1989 and 1990, the overhead rate decreased, but to a much lesser extent than the previous year, as direct

labor and overhead costs remained relatively stable. Furthermore, whereas sales rose by nearly 5%, the facilitys

overhead only increased by about 1.6%. While fixed costs within overhead contribute to this difference, efforts to

increase workers efficiency also likely were a factor. For example, the labor time to change dies improved from twelve

hours to ninety minutes, while workers uptime increased from 30% to 65%. Such improvements helped reduce costs

incurred by both direct and indirect labor.

In order to ascertain the effects of the ACFs decision to outsource mufflers and oil pans, I calculated the

expected gross margins of two hypothetical products using the facilitys 1988 and 1990 budgets (Exhibits 2 and 3). The

nearly 30% increase in the ACFs overhead allocation rate would have drastic effects on the gross margins of these

products, which respectively decreased by 55% and 35%, due to the added overhead burden. Although the ACF was able

to outsource substandard products and thereby reduce operating costs, it also negatively impacted the gross margins of its

products, which had to carry additional fixed costs (as highlighted by the increased overhead rate).

iii. Cost System Deficiencies

After a careful investigation of the ACFs allocation of overhead, it became clear to us that the facility is not operating

under an appropriate cost system, especially in regard to strategic decision making. In particular, the facilitys use of

single cost driverdirect labor costhas been impeding its ability to accurately allocate budgeted overhead, as one input

cannot drive the costs of all overhead accounts (for example, Account 8000, which is depreciation on machinery).

Furthermore, direct labor itself has limitations as a cost driver, since a significant portion of the facilitys activities are

carried out by machinery (which in turn increases the ACFs overhead, increasing its significance to the facilitys budget).

The use of machinery causes direct labor to decline in importance as a productive input and, as a result, it becomes less

appropriate as a cost driver. Therefore, if the ACF is inappropriately allocating its overheadwhich makes up a large

proportion of total production costsit likely cannot arrive at appropriate strategic decisions, as demonstrated by the

seemingly unwise decision to outsource products and consequently experience sharp decreases in gross margins.

iv. Estimated Model Budgets

In order to determine if the ACF should outsource its production of manifolds, we estimated its 1991 model budget under

two scenarios: the continued production of manifolds and the outsourcing of manifolds. Under the first set of

circumstances, which also assume that selling prices, volumes, and material costs remain the same, we determined that the

1991 budget would be identical to that of 1990 (Exhibit 4).

However, if the manifold is outsourced and the same variables (s elling prices, volumes, and material cost)

remain the same, there will be several items affected on the 1991 model budget (Exhibit 5). Firstly, we would drop all

direct material and direct labor costs for manifolds, as they would no longer be incurred. We would also lose any sales

corresponding to the production of manifolds. Furthermore, we must account for the overhead costs that are currently

allocated to manifolds, and either allocate them appropriately to the other products or consider them avoidable costs, as

they were indirectly related to the manifolds to some extent. In order to properly perform this analysis, we must

determine which costs are fixed and which are more variable compared to the output of manifolds.

Stainless steel exhaust manifolds are produced in a highly automated production process: the parts are loaded on

fixtures and robotically welded. Therefore, there are many more costs associated with machinerysuch as those incurred

by the engineers that use them, set ups, repairs, and spare partsthan the costs associated with the production laborers.

Since direct labor is used to allocate the overhead costs to products, we looked at the specific costs as a percentage of

direct labor to estimate how many overhead costs would be incurred if the ACF outsourced production of manifolds

(Exhibit 6).

1000 - Wages and benefits for non-skilled hourly labor decreased by $2,234 after the previous products were

dropped, meaning some of the costs were relative to the products. Looking at the percentage of direct labor. It

increased from 30.86% to 41.16% after the other products were dropped, meaning that some of the costs were

unavoidable. I estimate that the percentage of direct labor would be increased to 45%,

1500 Many salaried plant workers would remain as the manifolds are produced in a mostly automated fashion

and plan workers are not needed to work the machines. Removal of manifolds would increase percentage of

direct labor to 50% from 42.04% as the plant workers would still be needed for the other products.

Perry & Paul, LLP

2000 These production supplies are used on all products and are not very specific. Overhead to labor

percentage remained constant even through the outsourcing of the other two products. Therefore the outsourcings

of manifolds at 15% of direct labor will remain at that number.

3000 The small wearing tools are used on all products and are not very specific. Overhead to labor percentage

remained constant even through the outsourcing of the other two products. Therefore the outsourcings of

manifolds at 10% of direct labor will remain at that number.

4000 Some of the utilities would be avoided such as coal used in the manifolds production machines but others

would remain, thereby increasing percentage of direct labor from 52% to 60%.

5000 Some of the nonproduction employees costs that are used for plant maintenance could be avoided by

dropping but the manifolds as they would not be needed for maintenance on the equipment. Some costs would

still remain as many of them would still be needed for the other products. Therefore, percentage of direct labor

would increase from 144% to 160%.

8000 Depreciation costs would remain constant as the machines that are being used by the company currently

for manifolds would be sold therefore removing that depreciation cost. The percentage would increase a bit, due

to the loss of direct labor cost from manifolds from 27% to 30%.

9000 The various personnel costs would not be affected as much by the loss of the manifolds production as

there are not many employees involved with producing them as it is a largely automated procedure. Therefore

percentage of direct labor would increase from 42% to 50%.

11000 The project expense for the one time machine set up would be avoided as they would sell off the

equipment. The percentage would increase a bit, due to the loss of direct labor cost from manifolds from 22% to

25%.

12000 - These employee benefits are directly related to direct labor and therefore will decrease accordingly as

manifolds are no longer produced. Overhead to labor percentage remained constant even through the outsourcing

of the other two products. Therefore the outsourcings of manifolds at 111% of direct labor will remain at that

number.

14000 The benefits for the skilled workers directly related to the ones in 5000 category. In the same respect,

most of these costs will remain as manifolds are a mostly automated process. Therefore, the percent of direct

labor will increase from 57% to 70%.

Using these overhead costs as part of our analysis, we determined that the ACFs total profit would be $44,700 in 1991 if

manifolds were outsourced; on the other hand, if the ACF continues production of manifolds, its profit would be $63,501.

Furthermore, if the ACF continues producing manifolds, its overhead allocation rate would be 563%, which is the same as

the 1990 rate; in contrast, the allocation rate would increase to 626% if the facility outsources its production of manifolds.

III.

Recommendation

Our investigation of the ACFs cost system has revealed that it cannot currently be used for strategic decision making.

However, our office was able to gain a more accurate understanding of the facilitys cost structure through a detailed

analysis of its overhead accounts. As a result, we can confidently recommend the ACF to not outsource its production of

manifolds, on account of several major concerns. Firstly, sales of manifolds are absorbing a significant amount of

overhead costs; on the other hand, if the ACF outsources manifolds, a portion of this burdenthat is, fixed overhead costs

would be shifted to remaining products (as highlighted by the expected increase in allocation rate from 563% to 626%).

With additional burden, the gross margins of these remaining products would decrease, thereby driving down the ACFs

total profit as well. Although outsourcing reduces some of the ACFs operational costs, it cannot decrease fixed overhead

costs sufficiently, resulting in these negative financial effects. Furthermore, the facility has to consider that the market for

stainless steel manifolds may suddenly increase, presenting the ACF with potentially higher profits if it continues to

produce manifolds.

In addition to experiencing financial drawbacks, the ACF may also witness a significant drop in employee morale

if it outsources its production of manifolds, as doing so would result in a loss of jobs. Furthermore, employees may be led

to question their efforts to improve uptime and productivity, as manifolds would be outsourced regardless of such

improvements. If workers cease these efforts, the ACF may incur additional costs in both direct labor and overhead.

Perry & Paul, LLP

Before making a final decision, however, the ACF should conduct further market research and perhaps solicit

buyers for future order quantities and dates, as doing so may result in significantly more accurate budgeting. A market

survey may further reveal the actual potential for an increase in demand of stainless steel manifolds, which pose a large

growth opportunity for the ACF.

Finally, I strongly recommend that the

ACF explore activity-based cost

systems, as they are far more accurate

than the use single cost driver.

Since overhead costs make up a large

portion of the facilitys total costs,

it is especially crucial to trace these costs

Exhibit 1:

to their appropriate source. In

fact, doing so may reveal that another

product should be outsourced,

Overhead Allocation Rates

rather than manifolds. The ACF will be

much more able to achieve its

future goals if it can make strategic

decisions using an improved cost

system.

Year

1987

1988

1989

1990

Rate (% of Direct

Labor Cost)

437%

434%

577%

563%

Exhibit 2:

Exhibit 3:

Expected Gross Margin of

Product 1

Expected Gross Margin of

Product 2

Selling Price

Material Cost

Labor Cost

Overhead

Cost

Profit

Gross Margin

Change in

Gross Margin

1988

$62

$16

$6

1990

$62

$16

$6

$26.04

$33.78

$13.96

22.52

%

$6.22

10.03%

-55.46%

Selling Price

Material Cost

Labor Cost

Overhead

Cost

Profit

Gross Margin

Change in

Gross Margin

1988

$54

$27

$3

1990

$54

$27

$3

$13.02

$16.89

$10.98

20.33

%

$7.11

13.17%

-35.22%

Perry & Paul, LLP

Perry & Paul, LLP

Exhibit 4:

1991 Model Year Budget ($ 000), with Production of

Manifolds

Sales

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

Direct Materials

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

Direct Labor

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

Overhead

1000

1500

2000

3000

4000

5000

8000

9000

11000

12000

14000

Total

Overhead Allocation

Rate

Profit

83,535

93,120

49,887

0

0

$226,542

16,996

35,725

16,825

0

0

$69,546

4599

6540

2963

0

0

$14,102

5679

5928

2115

1410

7433

20,274

3744

5987

3030

15683

8110

$79,393

563%

$63,501

Perry & Paul, LLP

Exhibit 5:

1991 Model Year Budget ($ 000), with Outsourcing

of Manifolds

Sales

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

DM

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

DL

Tanks

Manifolds

Doors

Muffler

Oil pans

TOTAL

Overhead

1000

1500

2000

3000

4000

5000

8000

9000

11000

12000

14000

Total

Overhead Allocation

Rate

Profit

83,535

0

49,887

0

0

$133,422

16996

0

16,825

0

0

$33,821

4599

0

2963

0

0

$7562

3402.90

3781

1134.30

756.20

4537.20

12,099.2

0

2268.60

3781

1890.50

8393.82

5293.40

$47,338.

12

626%

$44,701

Perry & Paul, LLP

Exhibit 6:

Allocation Rate (% of Direct Labor Cost) for Individual Overhead Accounts

1000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

1500

Overhead Allocation

Rate

2000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

3000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

4000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

7713

31.25

%

6743

27.32

%

3642

14.76

%

2428

9.84%

8817

35.72

%

7806

30.86

%

6824

26.98

%

3794

15.00

%

2529

10.00

%

8888

35.14

%

5572

41.16

%

5883

43.46

%

2031

15.00

%

1354

10.00

%

7360

54.37

%

5679

40.27

%

5928

42.04

%

2115

15.00

%

1410

10.00

%

7433

52.71

%

5000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

8000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

9000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

11000

Overhead Allocation

Rate

24181

97.97

%

5964

24.16

%

6708

27.18

%

5089

20.62

%

24460

96.70

%

5946

23.51

%

6771

26.77

%

5011

19.81

%

20063

148.2

1%

3744

27.66

%

5948

43.94

%

3150

23.27

%

20274

143.7

7%

3744

26.55

%

5987

42.45

%

3030

21.49

%

12000

Overhead Allocation

26936

109.1

28077

111.0

15027

111.0

15683

111.2

3402.9

45.00

%

3781

50.00

%

1134.3

15.00

%

756.2

10.00

%

4537.2

60.00

%

12099.

2

160.00

%

2268.6

30.00

%

3781

50.00

%

1890.5

25.00

%

8393.8

2

111.00

You might also like

- Bridgeton Industries Case Study Analysis of Overhead AllocationDocument3 pagesBridgeton Industries Case Study Analysis of Overhead Allocationzxcv3214100% (1)

- Bridgeton Industries Case Study - Designing Cost SystemsDocument2 pagesBridgeton Industries Case Study - Designing Cost Systemsdgrgich0% (3)

- Wilkerson CompanyDocument4 pagesWilkerson Companyabab1990No ratings yet

- EX 1 - WilkersonDocument8 pagesEX 1 - WilkersonDror PazNo ratings yet

- Bridgeton HWDocument3 pagesBridgeton HWravNo ratings yet

- How Does Wilkerson's Existing Cost System Operate? Develop A Diagram To Show How Costs Flow From Factory Expense Accounts To ProductsDocument4 pagesHow Does Wilkerson's Existing Cost System Operate? Develop A Diagram To Show How Costs Flow From Factory Expense Accounts To ProductsKunal DhageNo ratings yet

- Berkshire Toy CompanyDocument25 pagesBerkshire Toy CompanyrodriguezlavNo ratings yet

- Group 8Document20 pagesGroup 8nirajNo ratings yet

- Davey Brothers Watch Co. and Classic Pen Company Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesDavey Brothers Watch Co. and Classic Pen Company Case Analysisabhishek pattanayakNo ratings yet

- Seligram Summary DetailsDocument6 pagesSeligram Summary DetailsSachin MailareNo ratings yet

- Costing Systems Reveal True Product MarginsDocument1 pageCosting Systems Reveal True Product Marginsfelipevwa100% (1)

- Seligram 2Document4 pagesSeligram 2Yvette YuanNo ratings yet

- Siemens CaseDocument4 pagesSiemens Casespaw1108No ratings yet

- Case Case:: Colorscope, Colorscope, Inc. IncDocument4 pagesCase Case:: Colorscope, Colorscope, Inc. IncBalvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Destin BrassDocument5 pagesDestin Brassdamanfromiran100% (1)

- Wilkerson Company Break Even Analysis for Multi-product SituationDocument5 pagesWilkerson Company Break Even Analysis for Multi-product SituationYAKSH DODIANo ratings yet

- 05 Wilkerson Company Solution - StudentsDocument9 pages05 Wilkerson Company Solution - StudentsVinyabhooshan Bajpai PGP 2022-24 Batch100% (1)

- WilkersonDocument4 pagesWilkersonmayurmachoNo ratings yet

- Wilkerson Case Assignment Questions Part 1Document1 pageWilkerson Case Assignment Questions Part 1gangster91No ratings yet

- MAC Davey Brothers - AkshatDocument4 pagesMAC Davey Brothers - AkshatPRIKSHIT SAINI IPM 2019-24 BatchNo ratings yet

- Analysis of PolysarDocument84 pagesAnalysis of PolysarParthMairNo ratings yet

- Case Study Beta Management Company: Raman Dhiman Indian Institute of Management (Iim), ShillongDocument8 pagesCase Study Beta Management Company: Raman Dhiman Indian Institute of Management (Iim), ShillongFabián Fuentes100% (1)

- Classic Pen CompanyDocument4 pagesClassic Pen CompanyGaurav Kataria0% (1)

- Seimens Electric Motor WorksDocument5 pagesSeimens Electric Motor WorksShrey BhalaNo ratings yet

- Wilkerson - Case Study1 PDFDocument2 pagesWilkerson - Case Study1 PDFPavanNo ratings yet

- Balakrishnan MGRL Solutions Ch14Document36 pagesBalakrishnan MGRL Solutions Ch14Aditya Krishna100% (1)

- Harvard Business School Chemical Bank Allocation of profitsDocument21 pagesHarvard Business School Chemical Bank Allocation of profitsMonisha SharmaNo ratings yet

- MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING - IIDocument5 pagesMANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING - IIshshank pandeyNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis of Colorscope, Inc.: Cost and Management AccountingDocument14 pagesCase Analysis of Colorscope, Inc.: Cost and Management AccountingRaghav SNo ratings yet

- BerkshireDocument12 pagesBerkshireShubhangi Satpute50% (2)

- Colorscope 1Document6 pagesColorscope 1Andrew NeuberNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Forner CarpetDocument4 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Forner CarpetLi CarinaNo ratings yet

- Daud Engine Parts CompanyDocument3 pagesDaud Engine Parts CompanyJawadNo ratings yet

- Color ScopeDocument10 pagesColor Scopedharti_thakare100% (1)

- SUBJECT: Analyses and Recommendations For The Different Cost AccountingDocument4 pagesSUBJECT: Analyses and Recommendations For The Different Cost AccountinglddNo ratings yet

- Dave BrothersDocument6 pagesDave BrothersSangtani PareshNo ratings yet

- Case ReichardDocument23 pagesCase ReichardDesiSelviaNo ratings yet

- Case 16-2Document3 pagesCase 16-2gusneri100% (1)

- Cost Accounting AssignmentDocument6 pagesCost Accounting AssignmentRamalu Dinesh ReddyNo ratings yet

- PIA Breakeven Analysis and Financial Performance ReportDocument3 pagesPIA Breakeven Analysis and Financial Performance ReportsaadsahilNo ratings yet

- Destin Brass Costing ProjectDocument2 pagesDestin Brass Costing ProjectNitish Bhardwaj100% (1)

- Wilkerson CompanyDocument2 pagesWilkerson CompanyAnkit VermaNo ratings yet

- Economic Impact of Oakland Athletics Ballpark at Howard TerminalDocument13 pagesEconomic Impact of Oakland Athletics Ballpark at Howard TerminalZennie AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Wilkerson Company ABCDocument4 pagesWilkerson Company ABCrajyalakshmiNo ratings yet

- Siemens Electric Motor WorksAQ PDFDocument3 pagesSiemens Electric Motor WorksAQ PDFHashirama SenjuNo ratings yet

- Cost Management - Software Associate CaseDocument7 pagesCost Management - Software Associate CaseVaibhav GuptaNo ratings yet

- DocxDocument3 pagesDocxbilalNo ratings yet

- Case Study South Dakota MicrobreweryDocument1 pageCase Study South Dakota Microbreweryjman02120No ratings yet

- Seligram Case QuestionsDocument2 pagesSeligram Case QuestionsZain Bharwani100% (1)

- Software Associates Case AnalysisDocument8 pagesSoftware Associates Case AnalysisMuhammad AsifNo ratings yet

- Sippican Case ReviewDocument9 pagesSippican Case ReviewDavid KijadaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Factory OverheadDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Factory Overheadafmcitjzc100% (1)

- ManopsDocument5 pagesManopsrory mcelhinneyNo ratings yet

- Chap 006Document16 pagesChap 006Tashkia0% (1)

- Managerial EconomicsDocument11 pagesManagerial EconomicsFrankNo ratings yet

- Maccounting BridgetonDocument4 pagesMaccounting Bridgetonsufyanbutt007No ratings yet

- Activity Based Costing Spring 2020 Answers Final - pdf-1Document20 pagesActivity Based Costing Spring 2020 Answers Final - pdf-1b21fa1201No ratings yet

- Wilkerson Case SubmissionDocument5 pagesWilkerson Case Submissiongangster91100% (2)

- SippicanDocument6 pagesSippicanMatija KaraulaNo ratings yet

- Overview FonderiaDocument11 pagesOverview Fonderia80starboy80No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- Pass Journal Entry If Debenture IsDocument2 pagesPass Journal Entry If Debenture IsalirazaNo ratings yet

- 1213212Document1 page1213212alirazaNo ratings yet

- Asslam o Alykum. How Are You? What Are You Doing? Tell Me About Own Self.Document1 pageAsslam o Alykum. How Are You? What Are You Doing? Tell Me About Own Self.alirazaNo ratings yet

- TH STDocument2 pagesTH STalirazaNo ratings yet

- Pass Journal Entry If Debenture IsDocument2 pagesPass Journal Entry If Debenture IsalirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- Pass Journal Entry If Debenture IsDocument1 pagePass Journal Entry If Debenture IsalirazaNo ratings yet

- Pass Journal Entry If Debenture IsDocument1 pagePass Journal Entry If Debenture IsalirazaNo ratings yet

- Pass Journal Entry If Debenture IsDocument1 pagePass Journal Entry If Debenture IsalirazaNo ratings yet

- QuestionnairDocument1 pageQuestionnairalirazaNo ratings yet

- 1213212Document2 pages1213212alirazaNo ratings yet

- I Com 2 Principles of Accounting Subjective: Time Allowed: 60 Minutes Total Marks: 40Document3 pagesI Com 2 Principles of Accounting Subjective: Time Allowed: 60 Minutes Total Marks: 40alirazaNo ratings yet

- How to prepare a feasibility reportDocument5 pagesHow to prepare a feasibility reportalirazaNo ratings yet

- Sm..3M CaseggggggggggDocument1 pageSm..3M CaseggggggggggalirazaNo ratings yet

- Shining Stars Academy: S. No. Date Subjects 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Document1 pageShining Stars Academy: S. No. Date Subjects 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9alirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- Mile High CycleDocument12 pagesMile High CycleAamir Abbas100% (1)

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- Wacc of InvestmentDocument7 pagesWacc of InvestmentalirazaNo ratings yet

- Mile High Cycles Flexible Budget AnalysisDocument4 pagesMile High Cycles Flexible Budget Analysisnino7578No ratings yet

- Ibd Library Is Filled With Great Documents Like Recipes, Presentations, Short Stories, How-To Guides, and EssaysDocument1 pageIbd Library Is Filled With Great Documents Like Recipes, Presentations, Short Stories, How-To Guides, and EssaysalirazaNo ratings yet

- sm..3M CaseDocument1 pagesm..3M CasealirazaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentalirazaNo ratings yet

- IBD Library Filled With Helpful DocumentsDocument1 pageIBD Library Filled With Helpful DocumentsalirazaNo ratings yet

- MayTag Corp - Understanding of Financial StatementDocument16 pagesMayTag Corp - Understanding of Financial StatementMirza JunaidNo ratings yet

- Profile of SQUARE PHARMACEUTICALS LTD by Biplob - BSP UIUDocument10 pagesProfile of SQUARE PHARMACEUTICALS LTD by Biplob - BSP UIUBiplob Sarkar100% (2)

- 18274compsuggans PCC Costacc Chapter8 PDFDocument8 pages18274compsuggans PCC Costacc Chapter8 PDFtnchsgNo ratings yet

- Internship Manual KUSTDocument27 pagesInternship Manual KUSTSaif Bettani KustNo ratings yet

- Morgan Town Inc. - Case HandoutDocument2 pagesMorgan Town Inc. - Case HandoutshivagajareNo ratings yet

- CSS Accounting & Auditing Topic-wise Past Papers: Marginal & Absorption CostingDocument3 pagesCSS Accounting & Auditing Topic-wise Past Papers: Marginal & Absorption CostingMasood Ahmad AadamNo ratings yet

- Altius Part3Document2 pagesAltius Part3Somil GuptaNo ratings yet

- Ex06 - Comprehensive BudgetingDocument14 pagesEx06 - Comprehensive BudgetingANa Cruz100% (2)

- HUL Financial AnalysisDocument11 pagesHUL Financial AnalysisRohit BhatejaNo ratings yet

- Bsbfim601 Manage Finances Monitor and Review BudgetDocument7 pagesBsbfim601 Manage Finances Monitor and Review BudgetAli Butt100% (7)

- Vending Machine Business Plan ExampleDocument33 pagesVending Machine Business Plan ExampleVincent ShareItNo ratings yet

- Project On Ratio AnalysisDocument64 pagesProject On Ratio AnalysisJyoshna BoddedaNo ratings yet

- ProposalDocument24 pagesProposalSushil BasnetNo ratings yet

- FP Report 2012Document180 pagesFP Report 2012CY LiuNo ratings yet

- Confidentiality Agreement for Business PlanDocument28 pagesConfidentiality Agreement for Business PlanGoBig Tulongeni HamukotoNo ratings yet

- Sample Staffing Account Executive Sales Commission Agreement TemplateDocument8 pagesSample Staffing Account Executive Sales Commission Agreement TemplateJohanna ShinNo ratings yet

- 7e Ch5 Mini Case AnalyticsDocument6 pages7e Ch5 Mini Case AnalyticsDaniela667100% (9)

- Case - Amazon Part II - Ratio AnalysisDocument13 pagesCase - Amazon Part II - Ratio AnalysisShuting QinNo ratings yet

- ModelDocument103 pagesModelMatheus Augusto Campos PiresNo ratings yet

- Bione EnterprisesDocument20 pagesBione EnterprisesShaneen Angelique MoralesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19Document51 pagesChapter 19Yasir MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Financial Aspects Ofmarketing ManagementDocument38 pagesFinancial Aspects Ofmarketing ManagementAli AlsayedNo ratings yet

- MSN Laboratories PVT Limited, Hyderabad: "A Study On Financial Performance"Document65 pagesMSN Laboratories PVT Limited, Hyderabad: "A Study On Financial Performance"Harish Kumar DaivamNo ratings yet

- Retail Math FormulasDocument12 pagesRetail Math FormulasVinod Joshi50% (2)

- Management Accounting Lecture Notes 2016 4 - Cfe Excerpt T8mwc6land7z7x8cld0w PDFDocument31 pagesManagement Accounting Lecture Notes 2016 4 - Cfe Excerpt T8mwc6land7z7x8cld0w PDFjj67% (3)

- Managerial Accounting An Introduction To Concepts Methods and Uses 11th Edition Maher Solutions ManualDocument37 pagesManagerial Accounting An Introduction To Concepts Methods and Uses 11th Edition Maher Solutions ManualKennethSparkskqgmr100% (15)

- Efficiency and Profitability of Small-Scale Cassava Production in Akure Area of Ondo State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesEfficiency and Profitability of Small-Scale Cassava Production in Akure Area of Ondo State, NigeriaEwedairo HabibllahiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank - Chapter18 FS AnalysisDocument83 pagesTest Bank - Chapter18 FS AnalysisMarvin Rae CadapanNo ratings yet

- Feasibility ReportDocument9 pagesFeasibility ReportDaniyalNo ratings yet

- Cost Behavior ExerciseDocument3 pagesCost Behavior ExerciseIftekhar Uddin M.D EisaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Financial Statements SummaryDocument71 pagesAnalyzing Financial Statements Summarymaryam J50% (2)