Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear: Synonyms

Uploaded by

jcachica21Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear: Synonyms

Uploaded by

jcachica21Copyright:

Available Formats

Anterior Cruciate

Ligament Tear

Synonyms

ICD-9 Codes

717.83

Chronic disruption of anterior

cruciate ligament

844.2

Acute anterior cruciate ligament

tear

ACL tear

Anterior cruciate insufficiency

Cruciate ligament tear

Internal derangement of knee

Torn cruciate

Definition

Femur

Anterior

cruciate

ligament

Tear

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Tibia

640

Figure 1 Lateral view of the

knee shows a

complete anterior

cruciate ligament tear.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a primary stabilizer of

the knee against anterior translation (Figure 1). A tear of the

ACL results from a rotational (twisting) or hyperextension force

applied to the knee joint that overcomes the strength of the

ligament. Although partial tears can occur, injuries involving the

ACL more often result in complete tears. Most ACL tears are

noncontact injuries. An ACL tear is often accompanied by a

significant meniscal tear. An ACL tear also can occur in

association with a tear of the medial collateral ligament or, more

rarely, with tears of the lateral ligaments or the posterior cruciate

ligament. Uncommonly, knee injuries that disrupt multiple

ligaments and result in knee instability also injure the popliteal

artery; this is a limb-threatening emergency.

Clinical Symptoms

Patients with ACL tears usually report sudden pain and giving

way of the knee from a twisting or hyperextension-type injury.

One third of patients report an audible pop as the ligament tears.

A patient who sustains an ACL tear during athletic activity

usually is unable to continue participating because of pain

and/or instability. The pain increases because an effusion caused

by bleeding into the joint (hemarthrosis) develops rapidly.

As the swelling resolves, the patient temporarily may have no

trouble moving the knee; however, if the tear is left untreated,

recurrent instability develops, particularly with attempts to return

to agility sports involving pivoting, running, or jumping.

Chronic knee instability from an untreated ACL tear can lead to

further meniscal and articular cartilage damage, with resulting

degenerative arthritis.

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

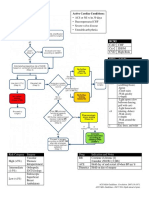

Figure 2 Lachman test. A, The knee is flexed approximately 30. The examiner gently pulls the tibia forward

with the medial hand while stabilizing the distal femur with the lateral hand. In a relaxed patient,

increased anterior translation of the tibia (in comparison to the uninjured knee) with a soft end point

constitutes a positive test. B, Diagram showing movement of the tibia relative to the femur.

Tests

The most sensitive test for ACL insufficiency is the Lachman

test, in which the knee is flexed to 30 and the tibia is gently

pulled forward while the femur is stabilized (Figure 2). It is

critical that the patients leg, especially the hamstrings, be

relaxed. Otherwise, an accurate examination cannot be

performed. Because of the subcutaneous location of the medial

tibia, it is easier to grasp the tibia on the medial side (right hand

for right knee, left hand for left knee) while stabilizing the

femur from the lateral side with the opposite hand. If the thigh

is large, the examiner may find it difficult to support the thigh in

one hand. In this situation, the examiner may place his or her

knee under the patients thigh. The examiner uses one hand to

stabilize the patients thigh in this position. The examiners other

hand gently elevates the tibia from the supported femur.

Increased motion of the tibia with no solid end point indicates a

tear of the ACL. The anterior drawer test, performed with the

knee flexed to 90, is negative in 50% of acute ACL tears and

thus is less helpful.

Diagnostic Tests

AP, lateral, and tunnel views of the knee should be ordered for

every patient with a suspected ACL tear. Usually these

radiographs are positive only for an effusion and possibly an

avulsion fracture of the lateral capsular margin of the tibia

(lateral capsular sign or Segond fracture); however, radiographs

are helpful in ruling out other pathology.

MRI is sensitive for detecting ACL tears. It also is extremely

useful for evaluating a knee with an acute effusion.

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Physical Examination

641

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

Differential Diagnosis

Fracture (tenderness over the bone, evident on radiographs)

Meniscal tear (continued tenderness along the joint line, pain

or trapping with circumduction) (may occur with ACL tear)

Patellar dislocation/subluxation (positive apprehension sign

when displacing the patella laterally)

Patellar tendon or quadriceps rupture (inability to perform

straight-leg raise)

Posterior cruciate ligament tear (positive posterior drawer test,

firm end point on Lachman test)

Adverse Outcomes of the Disease

If left untreated, the recurring instability resulting from an ACL

tear may cause subsequent meniscal tears and degenerative

disease. The instability also makes successful return to

participation in agility sports such as soccer, football, or

basketball unlikely.

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Treatment

642

Initial treatment of an acute ACL injury includes rest, ice, and

the use of crutches until the patient is able to ambulate without

a limp. If the knee effusion (hemarthrosis) is tense, aspiration

may be indicated to relieve symptoms (see page 647). A knee

immobilizer or range-of-motion brace may be used for comfort

when necessary until acute pain subsides.

Early range-of-motion exercises are important. With the

patient sitting, the injured knee should be actively extended and

flexed as comfort allows. Exercises should be performed

repeatedly for several minutes four or five times daily. Full

extension and flexion should be regained as soon as pain and

swelling permit.

Definitive treatment of an ACL injury depends on the

patients age and desired activity level and any associated

injuries. For young, active patients, ACL reconstruction offers

the best chance for a successful return to agility sports. Older or

less active individuals may be treated with physical therapy

aimed at controlling the instability. ACL functional bracing also

may be helpful with older or less active patients, but it usually

does not provide sufficient stability for most younger patients to

return to sports.

Rehabilitation Prescription

The goal of initial treatment of a torn ACL is to control the

inflammation and pain with rest, ice, compression, and elevation

(RICE) of the leg. In addition, maintaining the range of motion

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

and regaining muscle strength are important to rehabilitation.

Strengthening of the quadriceps and particularly the hamstring

muscle group, as in balance training, is critical for knee stability

following an ACL injury. Excessive anterior shearing forces

during knee extension from 60 to 0, especially from 30 to

10, can cause damage, as can varus and valgus stress in full

knee extension. Therefore, exercises that protect the ACL injury

by avoiding these ranges of motion and positions, such as

hamstring curls to strengthen the hamstring muscle group and

isometric quadriceps contraction and straight-leg raises to

strengthen the quadriceps, are used initially.

If instability, pain, and inflammation continue after 2 to

3 weeks, a formal rehabilitation program may be ordered. The

prescription should include an assessment of the strength of the

hip and trunk muscles, especially the hip external rotators and

abductors, as well as the knee, hamstring, and quadriceps

muscles. Outpatient rehabilitation for an ACL-deficient knee

should emphasize strengthening of these muscle groups as well

as neuromuscular training such as plyometrics and perturbation

training. In addition, the rehabilitation specialists evaluation

might include structural deviations that sometimes contribute to

ACL injury, such as a large Q angle, excessive foot pronation,

hip anteversion, and genu recurvatum and valgum, to help

determine the appropriate treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment carries the risk of recurrent instability,

meniscal tears, and degenerative joint disease. Scarring of the

knee joint (arthrofibrosis) with loss of motion can occur after

ACL injury or postoperatively after ACL reconstruction. Surgical

reconstruction carries several risks: the usual risks of surgery

(infection, phlebitis, pulmonary emboli, neurovascular insult,

scarring, etc); the possibility that the ACL can tear again; or

failure of the ACL graft to incorporate or successfully remodel,

resulting in recurrence of laxity. Fracture of the tibial or patellar

graft site also may occur after ACL reconstruction when a

portion of the patellar tendon is used for the ACL graft.

Referral Decisions/Red Flags

Patients with suspected ACL tears and/or posttraumatic knee

effusions require further evaluation and treatment. Even patients

who are not candidates for ACL reconstruction can benefit from

regular monitoring of the ACL tear.

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Adverse Outcomes of Treatment

643

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

Home Exercise Program for ACL Tear

Perform all five exercises in the order listed.

After each exercise session, apply ice (eg, a bag of crushed ice or a bag of frozen peas) to the knee

for 20 minutes or until numb, keep the leg elevated, and apply a compression bandage to the knee.

If pain or swelling increases at any time or if it does not improve after you have adhered to the

program for 3 to 4 weeks, call your doctor.

Exercise Type

Number of

Repetitions/Sets

Muscle Group

Number of Days

per Week

Number of

Weeks

Hamstring curls

(standing)

Hamstrings

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Straight-leg raises

Quadriceps

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Hip abduction

Gluteus medius

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Hip adduction

Adductor group

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Straight-leg raises (prone)

Gluteus maximus

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Wall slides

Quadriceps, hamstrings

20 repetitions/3 sets

4 to 5

3 to 4

Hamstring Curls

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

644

Stand on a flat surface with your weight evenly

distributed on both feet.

Hold onto the back of a chair or the wall for

balance.

Bend the injured knee, raising the heel of the

affected leg toward the ceiling as far as

possible without pain.

Hold this position for 5 seconds and then relax.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

Straight-Leg Raises

Lie on the floor, supporting your torso with

your elbows as shown.

Keep the injured leg straight and bend the

other leg at the knee so that the foot is flat on

the floor.

Tighten the thigh muscle of the injured leg and

slowly raise it 6 to 10 inches off the floor.

Hold this position for 5 seconds and then relax.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

Hip Abduction

Lie on your side with the injured side on top

and with the bottom leg bent to provide

support.

Slowly raise the top leg to 45, keeping the

knee straight.

Hold this position for 5 seconds.

Slowly lower the leg and relax it for

2 seconds.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

Lie down on the floor on the side of your

injured leg with both legs straight.

Cross the uninjured leg in front of the injured

leg.

Raise the injured leg 6'' to 8'' off the floor.

Hold this position for 5 seconds.

Lower the leg and rest for 2 seconds.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Hip Adduction

645

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT TEAR

Straight-Leg Raises (Prone)

Lie on the floor on your stomach with your

legs straight.

Tighten the hamstrings of the injured leg and

raise the leg toward the ceiling as far as you

can.

Hold this position for 5 seconds.

Lower the leg and rest it for 2 seconds.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

Wall Slides

SECTION 6 KNEE AND LOWER LEG

Lie on your back with the uninjured leg

extending through a doorway and the injured

leg extended against the wall.

Let the foot gently slide down the wall.

Hold this position of maximum flexion for

5 seconds and then slowly straighten the leg.

Perform 3 sets of 20 repetitions, 4 to 5 days a

week, continuing for 3 to 4 weeks.

646

E S S E N T I A L S O F M U S C U L O S K E L E TA L C A R E

2 0 1 0 A M E R I C A N A C A D E M Y O F O R T H O PA E D I C S U R G E O N S

You might also like

- ACL Injury: Everything You Need to Know to Make the Right Treatment Decision: - What the ACL does and why it is so important - Treatment options for partial and complete ACL tears - Surgery: graft options, how it is done, what to expect - How to prepare for surgery - What to dFrom EverandACL Injury: Everything You Need to Know to Make the Right Treatment Decision: - What the ACL does and why it is so important - Treatment options for partial and complete ACL tears - Surgery: graft options, how it is done, what to expect - How to prepare for surgery - What to dNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Meniscus with Acl Injury, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Meniscus with Acl Injury, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Exercises for Patella (Kneecap) Pain, Patellar Tendinitis, and Common Operations for Kneecap Problems: - Understanding kneecap problems and patellar tendinitis - Conservative rehabilitation protocols - Rehabilitation protocols for lateral release, patellar realignment, medial patellofemoral ligament reFrom EverandExercises for Patella (Kneecap) Pain, Patellar Tendinitis, and Common Operations for Kneecap Problems: - Understanding kneecap problems and patellar tendinitis - Conservative rehabilitation protocols - Rehabilitation protocols for lateral release, patellar realignment, medial patellofemoral ligament reRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rotator Cuff Injuries, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandRotator Cuff Injuries, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Knee Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentsFrom EverandKnee Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentsNo ratings yet

- Improving Ankle and Knee Joint Stability: Proprioceptive Balancefit Discs DrillsFrom EverandImproving Ankle and Knee Joint Stability: Proprioceptive Balancefit Discs DrillsNo ratings yet

- ACL Injury Conservative Management - Jul19Document4 pagesACL Injury Conservative Management - Jul19Tejesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament Strain (ACL Strain) : Forward Movement of The Tibia (Also Known As The Shin Bone)Document5 pagesAnterior Cruciate Ligament Strain (ACL Strain) : Forward Movement of The Tibia (Also Known As The Shin Bone)Sujith SujNo ratings yet

- ACL Injury PresentationDocument36 pagesACL Injury Presentationmail_rajibNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in PhysiotherapyFrom EverandRecent Advances in PhysiotherapyCecily PartridgeNo ratings yet

- Patient Guide To Acl Injuries: What Is The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) ?Document8 pagesPatient Guide To Acl Injuries: What Is The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) ?Subbu MNo ratings yet

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandPosterior Cruciate Ligament Injury, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Trochanteric Bursitis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandTrochanteric Bursitis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Everything You Wanted to Know About the Back: A Consumers Guide to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lower Back PainFrom EverandEverything You Wanted to Know About the Back: A Consumers Guide to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lower Back PainNo ratings yet

- Medial Meniscus Tears, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandMedial Meniscus Tears, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Avascular Necrosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAvascular Necrosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Hip Osteonecrosis A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHip Osteonecrosis A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Hallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Adhesive Capsulitis, (Frozen Shoulder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAdhesive Capsulitis, (Frozen Shoulder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Hip Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentFrom EverandHip Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Sprain and Strains, A Simple Guide to the Condition, Treatment and Related DiseasesFrom EverandSprain and Strains, A Simple Guide to the Condition, Treatment and Related DiseasesNo ratings yet

- ACL Rehabilitation ProgressionDocument8 pagesACL Rehabilitation ProgressionTomaž Radko Erjavec ŠnebergerNo ratings yet

- Synovial Chondromatosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandSynovial Chondromatosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Rehabilitation: A Person-Centred ApproachFrom EverandInterprofessional Rehabilitation: A Person-Centred ApproachSarah G. DeanNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Versus Stabilisation Exercise Programmes for Preventing and Reducing Low Back Pain in FemalesFrom EverandStrengthening Versus Stabilisation Exercise Programmes for Preventing and Reducing Low Back Pain in FemalesNo ratings yet

- Achilles RuptureDocument23 pagesAchilles RupturePhysiotherapist AliNo ratings yet

- Knee Surgery: The Essential Guide to Total Knee RecoveryFrom EverandKnee Surgery: The Essential Guide to Total Knee RecoveryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Herniated Disk, (Slipped Disk) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHerniated Disk, (Slipped Disk) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide to the Self-Management of Lower Back Pain: A Holistic Approach to Health and FitnessFrom EverandA Practical Guide to the Self-Management of Lower Back Pain: A Holistic Approach to Health and FitnessNo ratings yet

- Forearm Fractures, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandForearm Fractures, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament InjuryDocument30 pagesAnterior Cruciate Ligament InjuryyohanNo ratings yet

- Lower back and neck pain (Translated): Do's and don'ts for a healthy backFrom EverandLower back and neck pain (Translated): Do's and don'ts for a healthy backNo ratings yet

- Cervical Radiculopathy, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandCervical Radiculopathy, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Back Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentFrom EverandBack Disorders, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Improvised TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Interactions between the Craniomandibular System and Cervical Spine: The influence of an unilateral change of occlusion on the upper cervical range of motionFrom EverandInteractions between the Craniomandibular System and Cervical Spine: The influence of an unilateral change of occlusion on the upper cervical range of motionNo ratings yet

- Flat Foot (Pes Planus), A Simple Guide to The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandFlat Foot (Pes Planus), A Simple Guide to The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Introduction PhysiotherapistDocument12 pagesIntroduction Physiotherapistapi-371068989No ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to The Posture, Spine Diseases and Use in Disease DiagnosisFrom EverandA Simple Guide to The Posture, Spine Diseases and Use in Disease DiagnosisNo ratings yet

- Meniscus Injuries, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandMeniscus Injuries, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Sternum Disorders, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Sternum Disorders, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate and Expanded Stem Cell Applications in OrthopaedicsFrom EverandBone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate and Expanded Stem Cell Applications in OrthopaedicsNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Slouching Posture, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Slouching Posture, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- An Insider's Guide to Orthopedic Surgery: A Physical Therapist Shares the Keys to a Better RecoveryFrom EverandAn Insider's Guide to Orthopedic Surgery: A Physical Therapist Shares the Keys to a Better RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Modern Methods for Affordable Clinical Gait Analysis: Theories and Applications in Healthcare SystemsFrom EverandModern Methods for Affordable Clinical Gait Analysis: Theories and Applications in Healthcare SystemsNo ratings yet

- Claw Hand, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandClaw Hand, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Management of Patellofemoral Pain SyndromeDocument9 pagesManagement of Patellofemoral Pain Syndromethe M fingerNo ratings yet

- Periop Risk Strat JSDocument1 pagePeriop Risk Strat JSjcachica21No ratings yet

- Stats Review - High Value CasesDocument1 pageStats Review - High Value Casesjcachica21No ratings yet

- PneumoniaDocument5 pagesPneumoniajcachica21No ratings yet

- Abx Bacterial PneumDocument3 pagesAbx Bacterial Pneumjcachica21No ratings yet

- IM - Simple NotesDocument44 pagesIM - Simple Notesjcachica21No ratings yet

- Antivirals ChartDocument3 pagesAntivirals Chartjcachica21No ratings yet

- Gynecology and Obstetrics Abbreviations GuideDocument1 pageGynecology and Obstetrics Abbreviations Guidejcachica21No ratings yet

- TB MacDocument5 pagesTB Macjcachica21No ratings yet

- Amphotericin and CaspofunginDocument2 pagesAmphotericin and Caspofunginjcachica21No ratings yet

- H and P - PBL Interviewing ToolDocument2 pagesH and P - PBL Interviewing ToolPoojaPatelNo ratings yet

- Rotator Cuff TearDocument6 pagesRotator Cuff Tearjcachica21No ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis of HipDocument3 pagesOsteoarthritis of Hipjcachica21No ratings yet

- Successtypes in Medical EducationDocument222 pagesSuccesstypes in Medical EducationMarten HumphreyNo ratings yet

- Good and Cheap CookbookDocument67 pagesGood and Cheap CookbookSouthern California Public Radio100% (7)

- MuseScore enDocument78 pagesMuseScore enpdfs2003No ratings yet

- ISEF GuidelinesDocument26 pagesISEF GuidelinesShinjiro OdaNo ratings yet

- Medical Economics Magazine PDFDocument41 pagesMedical Economics Magazine PDFxtineNo ratings yet

- Premium Metal-Guard® 65, 75, 100, 150 MSDSDocument2 pagesPremium Metal-Guard® 65, 75, 100, 150 MSDSrahul chandranNo ratings yet

- ABRO Cellulose Thinners MIS42305Document8 pagesABRO Cellulose Thinners MIS42305singhajitb67% (3)

- Qualitative Study On Barriers To Access From The Perspective of Patients and OncologistsDocument6 pagesQualitative Study On Barriers To Access From The Perspective of Patients and OncologistsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 036 Urinay DisordersDocument8 pagesChapter - 036 Urinay DisordersClaudina CariasoNo ratings yet

- Oral Surgery and InfectionsDocument32 pagesOral Surgery and InfectionsTheSuperJayR100% (1)

- Minority Stress in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults in Australia Associations With Psychological Distress, Suicidality, and Substance UseDocument5 pagesMinority Stress in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults in Australia Associations With Psychological Distress, Suicidality, and Substance Useanna karolyne VilarNo ratings yet

- EN795 anchor devices standard updateDocument1 pageEN795 anchor devices standard updateMarcelo CostaNo ratings yet

- Acute Disease:: Above: Circles of Influence in Self-Management of Chronic DiseaseDocument10 pagesAcute Disease:: Above: Circles of Influence in Self-Management of Chronic DiseaseanburajjNo ratings yet

- TULUA Lipoabdominoplasty Transversal Aponeurotic.12Document14 pagesTULUA Lipoabdominoplasty Transversal Aponeurotic.12Carolina Ormaza Giraldo100% (1)

- Biosample Stool Collection Protocol InfantDocument2 pagesBiosample Stool Collection Protocol Infantapi-531349549No ratings yet

- EO Reactivitation of BADACDocument2 pagesEO Reactivitation of BADACArniel Fred Tormis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Toxic Responses To The LiverDocument18 pagesToxic Responses To The LiversaiibelievesNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics Nursing UnitDocument43 pagesPediatrics Nursing UnitShweta SainiNo ratings yet

- 2.medical HelminthologyDocument148 pages2.medical HelminthologyHanifatur Rohmah100% (2)

- Mineral Trioxide Aggregate A ComprehensiDocument14 pagesMineral Trioxide Aggregate A Comprehensifelipe martinezNo ratings yet

- 2008-02 MH IndiaDocument170 pages2008-02 MH IndiaHasan AzmiNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge Sharing For Prevention of Hepatitis Viral Infection Among Students of Higher Institutions of Kebbi State, NigeriaDocument9 pagesAssessment of Knowledge Sharing For Prevention of Hepatitis Viral Infection Among Students of Higher Institutions of Kebbi State, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Management of Open Fractures: Gibran T. AlpharianDocument21 pagesManagement of Open Fractures: Gibran T. AlpharianFerry RusdiansaputraNo ratings yet

- Junal ScreeningDocument9 pagesJunal ScreeningRama BayuNo ratings yet

- Multicenter Study For The Evaluation of Aminoacids Facial LiftingDocument7 pagesMulticenter Study For The Evaluation of Aminoacids Facial LiftingGustavo Henrique MüllerNo ratings yet

- Soares - Como Escolher Um Anestesico Local - 2005 PDFDocument9 pagesSoares - Como Escolher Um Anestesico Local - 2005 PDFjvb sobralNo ratings yet

- Students Readiness For The Face-To-Face Classes in Junior and Senior High SchoolDocument12 pagesStudents Readiness For The Face-To-Face Classes in Junior and Senior High SchoolIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Final Result For PG 2022 Stray Vacancy RoundDocument83 pagesFinal Result For PG 2022 Stray Vacancy RoundFaheem Peerzada HassanNo ratings yet

- Pfizer Remakes the CompanyDocument2 pagesPfizer Remakes the CompanyAlbert UmaliNo ratings yet

- Mind Control The Government Conspiracy Torture Human Enslavement and Retaliat PDFDocument60 pagesMind Control The Government Conspiracy Torture Human Enslavement and Retaliat PDFBrian BivinsNo ratings yet

- Apgvb Insurance Consent LetterDocument1 pageApgvb Insurance Consent LetterMahesh PasupuletiNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Solutions For Analysis of X-Ray ImagesDocument13 pagesArtificial Intelligence Solutions For Analysis of X-Ray ImagesYamah PrincewillNo ratings yet

- FHSIS Recording and Reporting Tools in Data Quality CheckDocument40 pagesFHSIS Recording and Reporting Tools in Data Quality CheckAnonymous h2EnKyDbNo ratings yet