Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Salumbides vs. Office of Ombudsman

Uploaded by

Van DicangCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Salumbides vs. Office of Ombudsman

Uploaded by

Van DicangCopyright:

Available Formats

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

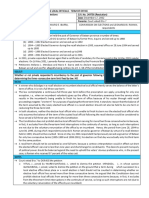

ATTY. VICENTE E. SALUMBIDES, JR., and GLENDA ARAA, Petitioners, vs. OFFICE OF

THE OMBUDSMAN, RICARDO AGON, RAMON VILLASANTA, ELMER DIZON, SALVADOR

ADUL, and AGNES FABIAN, Respondents,

GR No. 180917

April 20, 2010

FACTS OF THE CASE:

Vicente Jr. (Salumbides) and Glenda (Arana), Municipal Legal Officer/Administrator and

Municipal Budget Officer, respectively, of Tagkaywayan, Quezon, along with Mayor Vicente III

(Salumbides) were charged administratively in connection with the construction of a twoclassroom building for the Tagkawayan Municipal High School, without the required

appropriation of the Sangguniang Bayan, and without public bidding, the funds for which they

sourced from the Maintenance and Other Operating Expenses/Repair and Maintenance of

Facilities (MOOE/RMF) for the year 2002, as was allegedly done by the previous administration.

Construction proceeded, and even after the project was included in the list of projects to be

bidder, no bidders participated. The other members of the Sangguniang Bayan then filed with

the Office of the Ombudsman an administrative case for Dishonesty, Grave Misconduct, Gross

Neglect of Duty, Conduct Prejudicial to the Best Interest of the Service, and violation of the

Commission on Audit (COA) Rules and the Local Government Code. By order of June 14, 2002,

the OMB denied the prayer for issuance of preventive suspension order, and on February 1,

2005, approved on April 11, 2005, denied the motion for reconsideration but dropped Mayor

Vicente and Councilor Coleta from the charges in view of their reelection in the 2004 elections.

The OMB later found Vicente Jr. And Glenda liable for Simple Neglect of Duty and imposed a

six-month suspension upon them. Their motion for reconsideration denied, they elevated their

case to the Supreme Court after their petition for certiorari was denied by the CA. They argue

that the principle of condonation should be expanded to cover coterminous appointive officials

who were administratively charged along with the reelected official/appointing authority with

infractions allegedly committed during their preceding term.

RESOLUTION OF THE CASE:

For non-compliance with the rule on certification against forum shopping, the petition

merits outright dismissal. The verification portion of the petition does not carry a certification

against forum shopping[1].

The Court has distinguished the effects of non-compliance with the requirement of

verification and that of certification against forum shopping. A defective verification shall be

treated as an unsigned pleading and thus produces no legal effect, subject to the discretion of

the court to allow the deficiency to be remedied, while the failure to certify against forum

shopping shall be cause for dismissal without prejudice, unless otherwise provided, and is not

curable by amendment of the initiatory pleading[2].

Petitioners disregard of the rules was not the first. Their motion for extension of time to

file petition was previously denied by Resolution of January 15, 2008[3] for non-compliance with

the required showing of competent proof of identity in the Affidavit of Service. The Court, by

Resolution of March 4, 2008,[4] later granted their motion for reconsideration with motion to

admit appeal (Motion with Appeal) that was filed on February 18, 2008 or the last day of filing

within the extended period.

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

Moreover, in their Manifestation/Motion[5] filed a day later, petitioners prayed only for the

admission of nine additional copies of the Motion with Appeal due to honest inadvertence in

earlier filing an insufficient number of copies. Petitioners were less than candid when they

surreptitiously submitted a Motion with Appeal which is different from the first set they had

submitted. The second set of Appeal includes specific Assignment of Errors[6] and already

contains a certification against forum shoppin[7] embedded in the Verification. The two different

Verifications were notarized by the same notary public and bear the same date and document

number[8]. The rectified verification with certification, however, was filed beyond the

reglementary period.

Its lapses aside, the petition just the same merits denial.

Petitioners urge this Court to expand the settled doctrine of condonation[9] to cover

coterminous appointive officials who were administratively charged along with the reelected

official/appointing authority with infractions allegedly committed during their preceding term.

The Court rejects petitioners thesis.

More than 60 years ago, the Court in Pascual v. Hon. Provincial Board of Nueva

Ecija[10] issued the landmark ruling that prohibits the disciplining of an elective official for a

wrongful act committed during his immediately preceding term of office. The Court explained

that [t]he underlying theory is that each term is separate from other terms, and that the

reelection to office operates as a condonation of the officers previous misconduct to the extent

of cutting off the right to remove him therefor[11].

The Court should never remove a public officer for acts done prior to his present term of

office. To do otherwise would be to deprive the people of their right to elect their officers. When

the people elect[e]d a man to office, it must be assumed that they did this with knowledge of his

life and character, and that they disregarded or forgave his faults or misconduct, if he had been

guilty of any. It is not for the court, by reason of such faults or misconduct[,] to practically

overrule the will of the people[12]. (underscoring supplied)

Lizares v. Hechanova, et al[13]l. replicated the doctrine. The Court dismissed the petition

in that case for being moot, the therein petitioner having been duly reelected, is no longer

amenable to administrative sanctions[14].

Ingco v. Sanchez, et al[15]. clarified that the condonation doctrine does not apply to a

criminal case[16]. Luciano v. The Provincial Governor, et al[17]., Olivarez v. Judge Villaluz,[18]

and Aguinaldo v. Santos[19] echoed the qualified rule that reelection of a public official does not

bar prosecution for crimes committed by him prior thereto.

Consistently, the Court has reiterated the doctrine in a string of recent jurisprudence

including two cases involving a Senator and a Member of the House of Representatives[20].

Salalima v. Guingona, Jr[21]. and Mayor Garcia v. Hon. Mojica[22]a reinforced the

doctrine. The condonation rule was applied even if the administrative complaint was not filed

before the reelection of the public official, and even if the alleged misconduct occurred four days

before the elections, respectively. Salalima did not distinguish as to the date of filing of the

administrative complaint, as long as the alleged misconduct was committed during the prior

term, the precise timing or period of which Garcia did not further distinguish, as long as the

wrongdoing that gave rise to the public officials culpability was committed prior to the date of

reelection.

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

Petitioners theory is not novel.

A parallel question was involved in Civil Service Commission v. Sojor[23] where the

Court found no basis to broaden the scope of the doctrine of condonation:

Lastly, We do not agree with respondents contention that his appointment to the position

of president of NORSU, despite the pending administrative cases against him, served as a

condonation by the BOR of the alleged acts imputed to him. The doctrine this Court laid down in

Salalima v. Guingona, Jr. and Aguinaldo v. Santos are inapplicable to the present

circumstances. Respondents in the mentioned cases are elective officials, unlike respondent

here who is an appointed official. Indeed, election expresses the sovereign will of the people.

Under the principle of vox populi est suprema lex, the re-election of a public official may, indeed,

supersede a pending administrative case. The same cannot be said of a re-appointment to a

non-career position. There is no sovereign will of the people to speak of when the BOR reappointed respondent Sojor to the post of university president[24]. (emphasis and underscoring

supplied)lawph!l

Contrary to petitioners asseveration, the non-application of the condonation doctrine to

appointive officials does not violate the right to equal protection of the law.

In the recent case of Quinto v. Commission on Elections[25], the Court applied the fourfold test in an equal protection challenge[26] against the resign-to-run provision, wherein it

discussed the material and substantive distinctions between elective and appointive officials that

could well apply to the doctrine of condonation:

The equal protection of the law clause is against undue favor and individual or class

privilege, as well as hostile discrimination or the oppression of inequality. It is not intended to

prohibit legislation which is limited either in the object to which it is directed or by territory within

which it is to operate. It does not demand absolute equality among residents; it merely requires

that all persons shall be treated alike, under like circumstances and conditions both as to

privileges conferred and liabilities enforced. The equal protection clause is not infringed by

legislation which applies only to those persons falling within a specified class, if it applies alike

to all persons within such class, and reasonable grounds exist for making a distinction between

those who fall within such class and those who do not.

Substantial distinctions clearly exist between elective officials and appointive officials.

The former occupy their office by virtue of the mandate of the electorate. They are elected to an

office for a definite term and may be removed therefrom only upon stringent conditions. On the

other hand, appointive officials hold their office by virtue of their designation thereto by an

appointing authority. Some appointive officials hold their office in a permanent capacity and are

entitled to security of tenure while others serve at the pleasure of the appointing authority.

xxxx

An election is the embodiment of the popular will, perhaps the purest expression of the

sovereign power of the people. It involves the choice or selection of candidates to public office

by popular vote. Considering that elected officials are put in office by their constituents for a

definite term, x x x complete deference is accorded to the will of the electorate that they be

served by such officials until the end of the term for which they were elected. In contrast, there

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

is no such expectation insofar as appointed officials are concerned. (emphasis and

underscoring supplied)

The electorates condonation of the previous administrative infractions of the reelected

official cannot be extended to that of the reappointed coterminous employees, the underlying

basis of the rule being to uphold the will of the people expressed through the ballot. In other

words, there is neither subversion of the sovereign will nor disenfranchisement of the electorate

to speak of, in the case of reappointed coterminous employees.

It is the will of the populace, not the whim of one person who happens to be the

appointing authority, that could extinguish an administrative liability. Since petitioners hold

appointive positions, they cannot claim the mandate of the electorate. The people cannot be

charged with the presumption of full knowledge of the life and character of each and every

probable appointee of the elective official ahead of the latters actual reelection.

Moreover, the unwarranted expansion of the Pascual doctrine would set a dangerous

precedent as it would, as respondents posit, provide civil servants, particularly local government

employees, with blanket immunity from administrative liability that would spawn and breed

abuse in the bureaucracy.

Asserting want of conspiracy, petitioners implore this Court to sift through the evidence

and re-assess the factual findings. This the Court cannot do, for being improper and immaterial.

Under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, only questions of law may be raised, since the

Court is not a trier of facts[27]. As a rule, the Court is not to review evidence on record and

assess the probative weight thereof. In the present case, the appellate court affirmed the factual

findings of the Office of the Ombudsman, which rendered the factual questions beyond the

province of the Court.

Moreover, as correctly observed by respondents, the lack of conspiracy cannot be

appreciated in favor of petitioners who were found guilty of simple neglect of duty, for if they

conspired to act negligently, their infraction becomes intentiona[28]l. There can hardly be

conspiracy to commit negligence[29].

Simple neglect of duty is defined as the failure to give proper attention to a task

expected from an employee resulting from either carelessness or indifference[30]. In the present

case, petitioners fell short of the reasonable diligence required of them, for failing to exercise

due care and prudence in ascertaining the legal requirements and fiscal soundness of the

projects before stamping their imprimatur and giving their advice to their superior.

The appellate court correctly ruled that as municipal legal officer, petitioner Salumbides

failed to uphold the law and provide a sound legal assistance and support to the mayor in

carrying out the delivery of basic services and provisions of adequate facilities when he advised

[the mayor] to proceed with the construction of the subject projects without prior competitive

bidding[31]. As pointed out by the Office of the Solicitor General, to absolve Salumbides is

tantamount to allowing with impunity the giving of erroneous or illegal advice, when by law he is

precisely tasked to advise the mayor on matters related to upholding the rule of law.[32]

Indeed, a legal officer who renders a legal opinion on a course of action without any legal basis

becomes no different from a lay person who may approve the same because it appears

justified.

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

As regards petitioner Glenda, the appellate court held that the improper use of

government funds upon the direction of the mayor and prior advice by the municipal legal officer

did not relieve her of liability for willingly cooperating rather than registering her written

objection[33] as municipal budget officer.

Aside from the lack of competitive bidding, the appellate court, pointing to the improper

itemization of the expense, held that the funding for the projects should have been taken from

the capital outlays that refer to the appropriations for the purchase of goods and services, the

benefits of which extend beyond the fiscal year and which add to the assets of the local

government unit. It added that current operating expenditures like MOOE/RMF refer to

appropriations for the purchase of goods and services for the conduct of normal local

government operations within the fiscal year.[34]

In Office of the Ombudsman v. Tongson[35], the Court reminded the therein

respondents, who were guilty of simple neglect of duty, that government funds must be

disbursed only upon compliance with the requirements provided by law and pertinent rules.

Simple neglect of duty is classified as a less grave offense punishable by suspension without

pay for one month and one day to six months. Finding no alleged or established circumstance to

warrant the imposition of the maximum penalty of six months, the Court finds the imposition of

suspension without pay for three months justified.

When a public officer takes an oath of office, he or she binds himself or herself to

faithfully perform the duties of the office and use reasonable skill and diligence, and to act

primarily for the benefit of the public. Thus, in the discharge of duties, a public officer is to use

that prudence, caution, and attention which careful persons use in the management of their

affairs[36].

Public service requires integrity and discipline. For this reason, public servants must

exhibit at all times the highest sense of honesty and dedication to duty. By the very nature of

their duties and responsibilities, public officers and employees must faithfully adhere to hold

sacred and render inviolate the constitutional principle that a public office is a public trust; and

must at all times be accountable to the people, serve them with utmost responsibility, integrity,

loyalty and efficiency[37].

WHEREFORE, the assailed Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R.

SP No. 96889 are AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION, in that petitioners, Vicente Salumbides, Jr.

and Glenda Araa, are suspended from office for three (3) months without pay.

DICANG, VAN OLIVER M.

Baguio City

You might also like

- 19 Comelec Vs Conrado CruzDocument1 page19 Comelec Vs Conrado Cruzmayton30100% (2)

- Dizon vs. ComelecDocument2 pagesDizon vs. ComelecMaryanJunkoNo ratings yet

- Taxation 2 by Sababan (Book+Magic& Pink Notes)Document111 pagesTaxation 2 by Sababan (Book+Magic& Pink Notes)Clambeaux100% (2)

- Sanggunian of Brgy Don Mariano Marcos V.martinezDocument2 pagesSanggunian of Brgy Don Mariano Marcos V.martinezMaria Raisa Helga YsaacNo ratings yet

- Talaga Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesTalaga Vs ComelecYvonne Bioyo-Tulang100% (2)

- Dimapilis Vs ComelecDocument6 pagesDimapilis Vs ComelecAraveug InnavoigNo ratings yet

- Adormeo Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesAdormeo Vs ComelecRaymond RoqueNo ratings yet

- Pvs Vera Probation vs PardonDocument1 pagePvs Vera Probation vs PardonNur OmarNo ratings yet

- Montuerto v. Ty DigestDocument2 pagesMontuerto v. Ty DigestArnold Rosario ManzanoNo ratings yet

- SC rules OMB cannot hold reelected mayor liableDocument1 pageSC rules OMB cannot hold reelected mayor liableJaja GkNo ratings yet

- Digest - CBEA V BSPDocument2 pagesDigest - CBEA V BSPMaria Anna M LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Castillo Poli Saño v. COMELECDocument4 pagesCastillo Poli Saño v. COMELECkjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- Coconut Oil Refiners Vs TorresDocument2 pagesCoconut Oil Refiners Vs TorresPeanutButter 'n JellyNo ratings yet

- LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTSDocument34 pagesLABOR LAW CASE DIGESTSLenette Lupac100% (1)

- City of Naga v. AsuncionDocument3 pagesCity of Naga v. AsuncionNaj NoskcireNo ratings yet

- Salalima vs. GuingonaDocument1 pageSalalima vs. GuingonaMikkoletNo ratings yet

- Rivera Iii V Comelec (1991) : Term Limits - Sandoval-Gutierrez, J. - G.R. No. 167591, G.R. No. 170577Document2 pagesRivera Iii V Comelec (1991) : Term Limits - Sandoval-Gutierrez, J. - G.R. No. 167591, G.R. No. 170577Chelle BelenzoNo ratings yet

- Ichong vs Hernandez Upholds Constitutionality of Act Regulating Retail BusinessDocument5 pagesIchong vs Hernandez Upholds Constitutionality of Act Regulating Retail BusinessAJ Aslarona83% (12)

- Araullo Vs Aquino III: A Case DigestDocument12 pagesAraullo Vs Aquino III: A Case DigestMarlouis U. Planas94% (35)

- Election Law DigestsDocument5 pagesElection Law DigestsIrrah Su-ayNo ratings yet

- Asean Pacific Planners v. City of UrdanetaDocument2 pagesAsean Pacific Planners v. City of UrdanetaAce DiamondNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Filed Over Deputy-Involved Fatal ShootingDocument30 pagesLawsuit Filed Over Deputy-Involved Fatal ShootingKHOUNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Protections of Civil Liberties and the Hierarchy of RightsDocument77 pagesConstitutional Protections of Civil Liberties and the Hierarchy of RightsRolly HeridaNo ratings yet

- Lingating Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesLingating Vs ComelecRaymond Roque100% (1)

- Mendoza v. Commission On ElectionsDocument2 pagesMendoza v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Taxes are the Lifeblood of GovernmentDocument23 pagesTaxes are the Lifeblood of GovernmentVikki AmorioNo ratings yet

- Alvarez Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesAlvarez Vs ComelecVittorio Ignatius RaagasNo ratings yet

- Lingating v. ComelecDocument3 pagesLingating v. ComeleckathrynmaydevezaNo ratings yet

- Abundo, Sr. V Comelec GR No. 201716Document2 pagesAbundo, Sr. V Comelec GR No. 201716Adfat Pandan100% (2)

- Plaza V CADocument2 pagesPlaza V CAMaddie BautistaNo ratings yet

- h. Villarica Pawnshop, Inc. v. Social Security Commission, Social Security System, Amador m. Monteiro, Santiago Dionisio r. Agdeppa, Ma. Luz n. Barros-magsino, Milagros n. Casuga and Jocelyn q. Garcia (g.r. No. 228087. January 24, 2018.* )Document16 pagesh. Villarica Pawnshop, Inc. v. Social Security Commission, Social Security System, Amador m. Monteiro, Santiago Dionisio r. Agdeppa, Ma. Luz n. Barros-magsino, Milagros n. Casuga and Jocelyn q. Garcia (g.r. No. 228087. January 24, 2018.* )Ab CastilNo ratings yet

- Ong Vs Comelec (Digest)Document2 pagesOng Vs Comelec (Digest)Kitchie San Pedro100% (1)

- Cases Digests On Local Government CodeDocument20 pagesCases Digests On Local Government CodeVan DicangNo ratings yet

- Cases Digests On Local Government CodeDocument20 pagesCases Digests On Local Government CodeVan DicangNo ratings yet

- 2018 Boston Finance and Investment Corporation v. Candelario v. Gonzalez PDFDocument13 pages2018 Boston Finance and Investment Corporation v. Candelario v. Gonzalez PDFChesca MayNo ratings yet

- CSC Vs SojorDocument3 pagesCSC Vs SojorManuel AlamedaNo ratings yet

- 77) Navarro and Tamayo V CADocument2 pages77) Navarro and Tamayo V CAStephanie Griar100% (1)

- Javellana Vs LuteroDocument3 pagesJavellana Vs LuteroVirna SilaoNo ratings yet

- Administrative Investigations and Appeals: Midnight AppointmentsDocument2 pagesAdministrative Investigations and Appeals: Midnight AppointmentsGRNo ratings yet

- Man convicted of illegal firearm possession appeals rulingDocument7 pagesMan convicted of illegal firearm possession appeals rulingcg__95No ratings yet

- Siawan Vs InopiquezDocument1 pageSiawan Vs InopiquezNormita SechicoNo ratings yet

- Digest Albania vs. TalladoDocument1 pageDigest Albania vs. TalladoKriselle Joy ManaloNo ratings yet

- Mamerto Sevilla Vs ComElecDocument15 pagesMamerto Sevilla Vs ComElecJohnday MartirezNo ratings yet

- Lonzanida Vs COMELEC DigestDocument2 pagesLonzanida Vs COMELEC DigestgraceNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Ruling on Election Protests in Sulu ProvinceDocument3 pagesCOMELEC Ruling on Election Protests in Sulu ProvinceALIYAH MARIE ROJONo ratings yet

- Serrano v. Gallant Maritime Services, Inc. and Marlow Navigation Co., LTD DIGESTDocument4 pagesSerrano v. Gallant Maritime Services, Inc. and Marlow Navigation Co., LTD DIGESTxxxaaxxxNo ratings yet

- Cocofed V RepublicDocument2 pagesCocofed V RepublicGlewin DavidNo ratings yet

- Aratea V ComelecDocument4 pagesAratea V Comelecattyalan80% (5)

- SEC v. Universal Rightfield Property Holdings, Inc., G.R. No. 181381Document12 pagesSEC v. Universal Rightfield Property Holdings, Inc., G.R. No. 181381Rhenfacel Manlegro100% (1)

- Meaning of Term Merely ExpiresDocument1 pageMeaning of Term Merely ExpiresraizaNo ratings yet

- LOI 869 upheld as valid energy measureDocument2 pagesLOI 869 upheld as valid energy measureLiz Lorenzo100% (1)

- Atty Salumbides V OmbudsmanDocument2 pagesAtty Salumbides V OmbudsmanAnnHopeLoveNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestMarlon Jessie NapalanNo ratings yet

- Mastura v. COMELECDocument2 pagesMastura v. COMELECSimeon Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Election Law I-IVDocument74 pagesElection Law I-IVAnonymous rpayYFB3PwNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 198860 July 23, 2012 ABRAHAM RIMANDO, PetitionerDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 198860 July 23, 2012 ABRAHAM RIMANDO, PetitionerKaren Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Seeks Revocation of Judge's Order Cancelling Writ of ExecutionDocument1 pagePetitioner Seeks Revocation of Judge's Order Cancelling Writ of ExecutionKresnie Anne Bautista100% (1)

- 04 - Republic Vs RambuyongDocument2 pages04 - Republic Vs RambuyongRogelio Rubellano IIINo ratings yet

- 183 Time of Arrest People vs. CalimlimDocument2 pages183 Time of Arrest People vs. CalimlimChristopher Anniban SalipioNo ratings yet

- Angobung Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesAngobung Vs Comelecemman2g.2baccay100% (1)

- Garchitorena Vs CresciniDocument1 pageGarchitorena Vs CresciniMarc Lester Hernandez-Sta AnaNo ratings yet

- Sales Vs Comelec Case DigestDocument1 pageSales Vs Comelec Case DigestStella MarianitoNo ratings yet

- Agra Case DigestDocument4 pagesAgra Case DigestArdenNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Aratea V. Comelec G.R. No. 195229, 09 October 2012Document2 pagesFacts:: Aratea V. Comelec G.R. No. 195229, 09 October 2012loschudentNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Brewing ControversiesDocument2 pagesIn The Matter of Brewing ControversieskookNo ratings yet

- V. COA: Nini Lanto v. COA Topic: Public Office and Responsibility FactsDocument2 pagesV. COA: Nini Lanto v. COA Topic: Public Office and Responsibility FactsPJANo ratings yet

- Soto Vs JarenoDocument1 pageSoto Vs JarenoTricia Sibal100% (1)

- Lozada V Bracewell DigestDocument3 pagesLozada V Bracewell DigestMickey OrtegaNo ratings yet

- September 3Document24 pagesSeptember 3Eisley SarzadillaNo ratings yet

- Jalosjos Vs COMELEC G.R. No. 205033 LOPEZ ATHENA D.Document4 pagesJalosjos Vs COMELEC G.R. No. 205033 LOPEZ ATHENA D.Marie Angelica NacionalesNo ratings yet

- Cemco Holdings Inc v. National Life Insurance - Jurisdiction of SECDocument4 pagesCemco Holdings Inc v. National Life Insurance - Jurisdiction of SECErika GallegoNo ratings yet

- Montebon vs. COMELECDocument1 pageMontebon vs. COMELECOnnie LeeNo ratings yet

- Political Law - ABC Party List v. Comelec, G.R. No. 193256, March 22, 2011Document2 pagesPolitical Law - ABC Party List v. Comelec, G.R. No. 193256, March 22, 2011Dayday Able100% (1)

- Condonation doctrine does not apply to appointive officialsDocument20 pagesCondonation doctrine does not apply to appointive officialsArjan Jay Arsol ArcillaNo ratings yet

- DILG Baguio Rbi Census Form 2012Document2 pagesDILG Baguio Rbi Census Form 2012Van Dicang100% (1)

- Resolution Expressing Opposition To SM Baguio Development of Luneta HillDocument2 pagesResolution Expressing Opposition To SM Baguio Development of Luneta HillVan DicangNo ratings yet

- Energy Consumption by Sector: 1999 Data: Sectors Percentage (In Thousand Metric Tons of Oil Equivalent)Document5 pagesEnergy Consumption by Sector: 1999 Data: Sectors Percentage (In Thousand Metric Tons of Oil Equivalent)Van DicangNo ratings yet

- Marcos V ManglapusDocument1 pageMarcos V ManglapusVan DicangNo ratings yet

- SLOVAKIA Vs Hungary (International Law)Document1 pageSLOVAKIA Vs Hungary (International Law)Van DicangNo ratings yet

- 47 - Dumlao V Comelec, 96 SCRA 392Document12 pages47 - Dumlao V Comelec, 96 SCRA 392gerlie22No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 190582Document28 pagesG.R. No. 190582Stud McKenzeeNo ratings yet

- Consti OneDocument190 pagesConsti OnegretchengeraldeNo ratings yet

- Department of Education vs. San Diego (G.R. No. 89572)Document3 pagesDepartment of Education vs. San Diego (G.R. No. 89572)Vincent RachNo ratings yet

- GSIS Survivorship Pension CaseDocument9 pagesGSIS Survivorship Pension CaseRodolfoNo ratings yet

- Denali SmithDocument26 pagesDenali Smithlex treinenNo ratings yet

- Local Government Code - Full CasesDocument46 pagesLocal Government Code - Full CasesJanine Prelle DacanayNo ratings yet

- RA 9006 constitutionality and repeal of Sec. 67 OECDocument2 pagesRA 9006 constitutionality and repeal of Sec. 67 OECPiaNo ratings yet

- Due Process: OklahomaDocument6 pagesDue Process: OklahomaMarga LeraNo ratings yet

- DC Mayor ComplaintDocument28 pagesDC Mayor ComplaintJoe Newby100% (1)

- Loving V VirginiaDocument7 pagesLoving V VirginiaFrance De LunaNo ratings yet

- PASEI Vs DrilonDocument4 pagesPASEI Vs DrilonHariette Kim TiongsonNo ratings yet

- Mison V. Gallegos: Constitutional Law 2 Case DigestsDocument24 pagesMison V. Gallegos: Constitutional Law 2 Case DigestsAleezah Gertrude RegadoNo ratings yet

- Memorandum in Support of MotionDocument29 pagesMemorandum in Support of MotionAnthony WarrenNo ratings yet

- Boyko Tanov v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, United States Department of Justice, 443 F.3d 195, 2d Cir. (2006)Document10 pagesBoyko Tanov v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, United States Department of Justice, 443 F.3d 195, 2d Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chua v. Civil Service CommissionDocument15 pagesChua v. Civil Service CommissionAce SalutNo ratings yet

- Equality before law & Equal Protection under Article 14Document3 pagesEquality before law & Equal Protection under Article 14Aditi TNo ratings yet