Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pluralistic Planning For Multicultural Cities PDF

Uploaded by

Ted Hou YuanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pluralistic Planning For Multicultural Cities PDF

Uploaded by

Ted Hou YuanCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of the American Planning Association

ISSN: 0194-4363 (Print) 1939-0130 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjpa20

Pluralistic Planning for Multicultural Cities: The

Canadian Practice

Mohammad A. Qadeer

To cite this article: Mohammad A. Qadeer (1997) Pluralistic Planning for Multicultural Cities:

The Canadian Practice, Journal of the American Planning Association, 63:4, 481-494, DOI:

10.1080/01944369708975941

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944369708975941

Published online: 26 Nov 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1065

View related articles

Citing articles: 25 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjpa20

Download by: [Vancouver Island University]

Date: 26 September 2015, At: 21:55

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

Pluralistic

Plannin for

Multicu tural

Cities

Multiculturalism necessitates broadening the scope o f pluralism in planning. Ethnic minorities often require a

divergent set o f community services,

housing facilities and neighborhood

arrangements. The multinationalism

o f the global economy is further diversifying built forms and functions in

contemporary cities. Canada, an acknowledged multicultural society, has

encountered pressures to diversify the

way urban facilities, services and structures are provided. How the Canadian

planning system has been responding

to these pressures is the subject ofthis

article. Through case studies and illustrative examples, the article surveys

the range o f planning issues arising

from multiculturalism and describes

the patterns ofCanadian responses. I t

concludes by outlining lessons drawn

from Canadian experiences about how

multiculturalism extends the meaning

o f pluralism in planning.

Qadeer is a professor in the School o f

Urban and Regional Planning, Queens

University, Canada. His longstanding

interest in cross-cultural studies o f urban development and planning has led

to his exploration o f cultural-sensitive

planning in Western countries. On this

theme he has contributed a chapter,

Urban Planning and Multiculturalism

in Ontario, Canada, in Race Equality

and Planning, edited by Huw Thomas

and Vijay Krishnarayan (Avebury,

1994).

Journal of the American Planning

Association, Vol. 63, No. 4, Autumn

1997. OAmerican Planning

Association, Chicago, IL.

The Canadian Practice

Mohammad A. Qadeer

tree can be the source of neighborhood battles, as shown in Toronto

by the nature meets culture headlines in The Globe and Mail.

Italians and Portuguese like to keep trees short, allowing a better

view of the neighbours. Anglo-Saxons want trees to be tall and leafy,

blocking any views from and to neighborhood houses. The Chinese believe trees in front of a home bring bad luck. As if these different preferences were not enough, the city has strict bylaws that prohibit cutting

down trees, but allow pollarding (trimming trees into a high bush), which

is favored by Europeans (The Globe and Mail 1995a, A10). This example

illustrates how multiculturalism permeates even small details of urban

life. It also embodies the planning issues that arise from the cultural diversity of local populations, such as the uniformity of policies and standards, differences in citizens wants, equity in accommodating the needs

of divergent groups, and public versus private interests in the spatial expressions of cultural values.

These issues form the background of this article. The article has an

empirical bias in that it focuses on those institutional accommodations

to citizens cultural diversity that are observable in planning practice. It

delineates how ethnic minorities are finding their places in the planning

system and the changes in planning policies and standards that are occurring in response to cultural and social diversity. Thus the broad question addressed here is how multiculturalism has affected planning

policies and strategies in Canada.

Specifically, the article identifies the public issues arising from the

divergent requirements for space and services found in different ethnic

groups, and the Canadian planning systems responses. Canada is an

appropriate setting for studying these issues. It is an acknowledged

APA JOURNALAUTUMN 1997

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

multicultural society and is explicitly committed to

sustaining the cultural heritage of minorities. Its experiences may hold lessons for other countries with large

immigrant populations.

Mapping the Conceptual Terrain

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

This section identifies the areas or aspects of Canadian planning likely to be affected by cultural diversity.2To begin with, key terms should be defined.

Multiculturalism as a public philosophy acknowledges racial and cultural differences in a society and

encourages their sustenance and expression as constituent elements of a national social order (Fleras and

Elliott 1992; Muller 1993). This philosophy envisages

the society as a mosaic of beliefs, practices and customs, not as a melting pot assimilating different racial

and cultural groups. The Canadian Multiculturalism

Act of 1988 defines multiculturalism as a policy designed to preserve and enhance the multicultural heritage of Canadians while working to achieve the

equality of all. Multiculturalism has two defining

principles: (1) the right to practice and preserve heritage, collectively as well as individually; that is, not

only are Chinese or Ukranians free to speak their languages at home, but they also have the right to form

associations, organize communities, and practice their

customs and religions as a group; and (2) equality of

rights and freedoms under the law for all individuals and communities (Fleras and Elliott 1992, 22-3).

Both these principles have direct bearing on urban

planning.

Increasingly, the effectiveness of urban planning is

assessed by its responsiveness to citizens needs and

goals. Given that interests and preferences differ by

social class, race, gender, and cultural background, the

responsiveness of urban planning depends on its ability to accommodate citizens divergent social and cultural needs and to treat individuals and groups

equitably in meeting those needs. To fulfill these requirements, the first step is to eliminate overt discrimination on the one hand, and cultural biases in the use

of land, the housing market, and the provision of urban services on the other hand.

In Canada, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms

and the post-1960s social consensus against racism

have largely eliminated overt forms of discrimination,

particularly of the type, Blacks or Indians need not

apply. However, the cultural values embedded in historical practices, public policies, administrative procedures, and regulatory standards are another matter.

Planning policies and standards presumably are based

on universalist criteria. Often they are backed by historic practices and established professional conven-

1

482

APA JOURNAL AUTUMN 1997

tions. Yet they originate from social patterns and

cultural values of the dominant communities, namely,

in Canada, the English or the French. Torontos tree

bylaw, described earlier, is a case in point. A seemingly

neutral regulation about tree maintenance is in fact

an embodiment of English/European preferences.

Should this bylaw be amended to accommodate the

preferences of diverse communities, particularly now

that trees have become icons of a new environmentalism? How should competing values be balanced?

This is the challenge of dealing with cultural biases

embedded in historical practices.

A Rawlsian framework, Equity Planning, or Pareto

Optimality may be theoretical models for mediating

among competing interests, but they largely address

issues of economic distribution between the rich and

the p00r.~In practice, intercommunity equity in fulfilling social needs is often pursued through political

bargaining and administrative procedures. This is particularly the case with planning policies and regulations. A t present, it is enough to flag the cultural

predispositions of planning policies and standards as

the area of contentions arising from multiculturalism.

A second aspect of urban planning with a bearing

on multicultural communities is its reliance on property development as its instrument. Critics of urban

planning have long held its property-centered approach to be a factor that limits realization of its

promise to promote peoples welfare and equity, and

efficiency. Multiculturalism requires that planning instruments be both sensitive to and responsive to the

social needs of particular communities and therefore

calls all the more for people-centered approaches. Any

cleavage between social objectives and institutional instruments is further sharpened by multiculturalism;

the appropriateness of instruments can be called into

question on the grounds of their relevance to culturally diverse communities.

Probably the most striking impact of multiculturalism on urban planning comes from the presence of

ethnic neighborhoods and ethnic business enclaves.

The emergence of ethnic residential and business districts brings up an enduring concern of urban planning, namely, striking a balance between social

segregation and integration.

Urban planning has long espoused social integration as a guiding value (Gans 1961), aiming to promote communities mixed across races and classes. Yet,

a central process shaping urban structure is the spatial

clustering of activities and social groups based on the

advantages of agglomeration economies as well as on

community sentiments. Such clusters usually occur as

a result of the convergence of a multitude of individ-

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

ual choices and are seldom preplanned. They can take

forms as different as a theater district or a Ukrainian

village.

When the real estate market creates an ethnic concentration, pressure builds for the provision of appropriate services and regulations. In most such

situations, the ethnic communitys needs have to be

reconciled with the requirements of other residents of

an area and also with city-wide objectives. A balancing

act of public policy, making trade-offs among different

objectives and values, is called for.

The present public attitude toward ethnic concentrations reflects the notion that residential or business

concentrations arising from individual choices freely

exercised without prejudice to others should be sustained, whereas socially or racially homogeneous

neighborhoods formed through discriminatory practices and explicit or implicit exclusionary policies

should be recognized as prejudicial to the public interest. This distinction is based on structural factors:

those external to individuals (discriminatory practices

and policies) versus those internal to individuals (motivation and preference, free choice) (Moghaddam

1994, 246). Social segregation at the block or neighborhood level that arises from dispositional factors is

voluntary as long there are no barriers to others who

may want to live there. The acceptability of social segregation or integration in a city is determined by the

process of its formulation and by its function, not by

the density of concentration.

To sum up the foregoing discussion, multiculturalism affects urban planning in two ways. The first is

that it holds planning policies and standards up to the

light of social values and public goals. Are policies equitable both procedurally and substantively in satisfying the needs of diverse individuals and groups? Is

there a cultural bias in their universalist criteria? How

can the competing interests of mainstream and of minority communities be balanced?

Second, multiculturalism recognizes the legitimacy of ethnic neighbourhoods and enclaves. The

emergence of these spatial concentrations affects urban planning by precipitating questions about the internal structure of the city as a whole, and challenging

social policies to balance the advantages of neighborhood homogeneity with the public goals of openness

and equal access by all.

A fundamental effect of multiculturalism is to call

for pluralistic planning approaches and to question

unitary conceptions of public interest and the ideology of master plans. Davidoffs idea of pluralism as

a planning approach comes close to accommodating

multiculturalism (Davidoff 1965). His concept has

roots in equity and a commitment to open bargaining

among competing interests that make it particularly

relevant (Krumholz 1994). However, multiculturalism,

along with feminism, expands the definition of the interests to be accommodated beyond race and class,

and thus extends the meaning of pluralism. In pluralistic planning, performance measures for policies and

standards aim for the equal satisfaction of the needs

and preferences of diverse groups. These are the expected directions of change in planning as influenced

by multicultura1ism.The following sections examine

what actually is happening in multicultural Canada.4

Multiculturalism in Canada

Canada has been a multicultural country from its

beginning. In the mosaic of aboriginal cultures and

languages there, multiculturalism extends back to antiquity. The European settlement, though led by the

two founding communities of the British and the

French, also included Germans, Russians, Chinese,

and Ukrainians, among others. Thus, Canada had

been a multicultural society long before that was acknowledged in federal policy. Canada has long regarded itself as a mosaic of cultures, in contrast to the

United States, which is described by the metaphor of a

melting pot (Hayward 1922). This distinction, albeit

overdrawn, has shaped Canadian attitudes towards

multiculturalism. The Trudeau government in 1971

formally acknowledged a policy of multiculturalism

within a bilingual framework.. . . [to] support and encourage the various cultures and ethnic groups that

give structure and vitality to our society (House of

Commons, The Prime Ministers Statement 1971). In

1988, the Government proclaimed Canadas policy on

multiculturalism, recognizing and promoting the cultural and racial diversity of Canadian society and acknowledging the freedom of all members of Canadian

society to preserve, enhance, and share their cultural

heritage (Multiculturalism and Citizenship Canada

1991, 5-6). These policies have given official sanction

to a sociological reality; nonetheless, in practice, official multiculturalism neither ensures that all communities enjoy equal rights and social standing nor

stands as an unquestioned policy.sAs Porter observed,

the Canadian mosaic is organized vertically, with the

English as the top layer (Porter 1965).

How Multicultural is Canada?

The cultural characteristics of the Canadian population are measured by three indicators: ethnic origin,

status as an immigrant, and language(s) spoken at

home. Indicators yield different, though overlap-

APA JOUILVALAUTUMN 1997

1483

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

TABLE 1. Ethnic origins, Canada, 1991

Ethnicity:

Single Origins*

No.

26,994,045

%

(100.0%)

Total

19,199,790

(71.1)

British

French

East European

South European

Asian and African

Others

5,611,050

6,146,600

946,810

1,379,030

1,633,660

3,482,640

(20.8)

(22.8)

( 3.5)

( 5.1)

( 6.1)

(1 2.0)

Ethn icity:

Multiple Origins*

NO.

Total

7,794,250

(28.9)

British and others

French and others

Other combinations

2,516,840

425,190

4,852,220

( 9.3)

( 1.6)

(1 8.0)

*Only selected categories are reported

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

Source: Statistics Canada (CAT 93-31 5 )

ping images of Canadian society, but all reveal a wide

range of ethnic diversity.

In the 1991 census, a minority of the Canadian

population (44 percent) classified themselves as of either British or French origins only-the two founding

settler communities (table 1).The rest, a majority, either gave more than one ethnic origin or identified

themselves as being of nonfounding communities.

Ethnicity is a significant factor, then, in the personal

identity of the majority population.

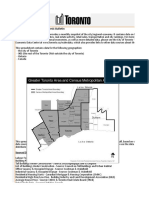

Another way of presenting the ethnic diversity of

the Canadian population is to review the proportions

of immigrant groups. In 1991, there were 4.3 million16 percent of the population-recent (post-1961) immigrants in Canada (Badets 1993, 1).Immigrants represented almost one-quarter of the population of

Ontario and British Columbia. Since most immigrants settle in metropolitan areas, Canadian cities

have become strikingly multicultural. In 1991, about

38 percent (1.5 million) of Metropolitan Torontos, 30

percent of Vancouvers, and 17 percent of Montreals

population were immigrants. Even second-tier cities

had high concentrations of immigrants: 24 percent in

Hamilton, 22 percent in Kitchener, 2lpercent in Windsor (Badets 1993, 10-1).

Historically, immigrants came from Europe, but

from 1971 onward the sources of immigration became

increasingly diverse ethnically. In the decade 19811991, Hong Kong was the birthplace of the largest

number of immigrants; Poland was second and the

Peoples Republic of China third. During that decade,

the majority of immigrants came from Asia or the

Middle East. Data show that more of the immigrants

are coming with high levels of education and professional skills (Badets 1993, 1).In 1991, 6.1 percent of

the Canadian population was of African or Asian origin, that is, they were visible minorities. Canada is also

becoming a polyglot country. In 1991, about 13 per-

484 APA JOURNAL-AUTUMN 1997

cent of the Canadian population reported a language

other than English or French as their mother tongue,

an increase from 11 percent in 1981.

On all three indicators-ethnic origins, immigrant

population percentages, and home language-ethnic

diversity in Canada is both wide-ranging and increasing in recent times. Cities are the loci of this multiculturalism. Multiculturalism in Canadian cities is not

altogether new, however, as the next section explains.

Multiculturalism: Old and New

Most thriving cities are multicultural. Phrases

such as babble of tongues and throngs of strangers

were coined to describe the social life of cities. Over

and above this general characteristic, Canadian cities

have long been strikingly multicultural on account of

continual immigration from abroad. Historically, immigrant ghettos and ethnic enclaves have been the emblems of urban Canadas multiculturalism. Winnipeg

in the 1920s, for example, was composed of a number

of subcommunities distinguished by ethnicity, religion, and class (Artibise 1977, 302). Torontos immigrant quarters were distinctly different from the main

city even in the 19th century. The question then is: If

multiculturalism is a long tradition of Canadian cities,

what is new about it that affects the planning system?

Contemporary ethnic studies distinguish between

old and new multiculturalism (Fleras and Elliott

1992). The old multiculturalism or cultural mosaic

was a private affair of immigrants, expected to dissolve

or be diluted with their assimilation (Harney 1985,

5-6; Fleras and Elliott 1992,317). It conferred no public rights. The old mosaic was confined to working

class, immigrant districts, typical of Burgess zone of

transitions, in the heart of a city.

The new mosaic is acknowledged by public

ideology and official policy. It is based on the postWorld War I1 notions of human rights and the

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

equality of citizens. Though still largely driven by immigration, the new mosaic is also sustained by the circulation across national borders of corporations,

labor, and information. Tourists and sojourning executives and professionals contribute to the new multiculturalism. The post-industrial economy and the rise

of internationalism and globalization have turned cultural diversity into an economic asset. At the same

time, they have also accelerated the diffusion of one

culture into another. Multiculturalism is, in the words

of one observer, the united colors of capitalism

(Mitchell 1993).

These changes mean that the new multiculturalism is not limited to the poor and to downtown core

areas. It has spread to suburbs, creating bourgeois ethnic enclaves. It has spawned new spatial and architectural forms. The result is that todays Canadian

metropolitan areas are having to consider the rights of

ethnics to organize their social lives in accordance

with their preferences and values. How such entitlements alter the planning system is observable in both

its planning process and its policies about neighborhood development, housing, and public services. I examine these aspects in the remainder of the article.

Multiculturalism, Social Diversity,

and the Planning Process

The cultural and racial diversity of citizens bears

on the planning process in three ways. First, it affects

the rational-technical component; race and culture

have become significant analytical categories for assessing public needs and analyzing social conditions.

Delineating neighborhoods by ethno-cultural criteria,

mapping catchment areas for community services

along socio-linguistic lines, and analyzing housing

conditions by race and ethnicity are examples of planning methodologies that are emerging with the acknowledgement of multiculturalism. They constitute

a paradigm shift in the methods of defining a local

community, as seen in the analytical work of planning departments.

Second, planners must now be sensitive to the

needs of individuals (and groups) in new ways, largely

in how they listen to clients and how they interpret

and apply regulations to them, particularly those in

minority communities. What treatment do persons of

color, unusual names, thick accents, or non-English or

non-French ancestry get from planning departments?

Are there systematic biases in planning procedures

and outlook that put minority communities at a disadvantage? The Royal (British) Town Planning Institute found that ethnic and racial minorities suffered

high refusal rates for development permissions (Krishnarayan and Thomas 1993, 23). No similar study for

Canada is known. Yet it is the case that ethnic communities often complain about getting short shrift from

planners.

Third, the scope and procedures of citizen involvement in the planning process have to be modified to

accommodate multicultural policies. It is on this score

that the planning process has shown the greatest responsiveness to the diversity of citizens.

Vancouver and Toronto have led in facilitating the

participation of ethnic communities in the making of

official plans. Vancouvers city plan process set up citizens circles in neighborhoods and invited ethnic

community associations, as well as individuals, to

identify needs and articulate their goals. Separate

info-lines were set up in four nonofficial languages

(Chinese, Punjabi, Spanish, Vietnamese) to give out information and receive comments (City of Vancouver

1993a). Similarly, Metropolitan Toronto and the City

of Toronto, separately, set up elaborate consultative

procedures that facilitate the participation of ethnic

communities. The City of Ottawa hstributes notices

and information about planning proposals in the heritage languages of an areas residents and regularly consults with ethnic community organizations. The

Winnipeg Core Area Plan has similarly attempted to

solicit the participation of Native and Ukrainian communities. All in all, the formal processes of citizen

involvement are beginning to be tailored specificallyto

include ethnic communities. In metropolitan centers,

then, the planning process is beginning to accommodate multiculturalism, at least in seeking the opinions

and input of minorities. The practice has not yet filtered down to small cities or the rest of the country,

where ethnic communities are not yet a significant political force.

The next step in pluralistic practices of planning

is to include minorities on decision-making bodies.

Torontos proposed official plan urges the city council

to include ethno-cultural and racial communities in

city committees and working groups (City of Toronto

1991, 13).Also important is the appointment co planning departments of professionals from minority

communities. The diversity of planners backgrounds

ensures appreciation of cultural and racial differences.

In the same vein, representation of minorities among

elected and nominated executives at local and provincial levels is a necessary condition for bringing a multicultural perspective to public decision-makingbodes.

On decision-making bodies, the progress towards accommodating multiculturalism is slower than that in

the participatory aspects of the planning process.

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

A planning process is a means for developing policies and programs to fulfill diverse needs and goals.

Ultimately, it is the relevance and appropriateness of

the policies and programs themselves that determine

how well planning accommodates diversity. The next

section therefore turns to planning issues that arise

at the neighborhood level, where multiculturalism is

most evident.

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

Neighborhood Planning: Stability and Change

Historically, ethnic residential concentrations have

been features of Canadian cities. Toronto, Montreal,

and Vancouver, of course, had Chinese, French, Jewish,

and Italian districts in the late 19th century. Prairie

cities had sizable concentrations of Eastern Europeans

and Natives, and even a small town, Fort William, Ontario, had a Finnish colony. Clearly, residential segregation by ethnicity and class has been an historical feature

of Canadian cities. Kalbach concludes from an analysis

of residential segregation in Toronto that sociocultural assimilation reflected in declining residential

segregation through successive generations can be

found only in a few populations of British and other

Western and Northern European origins (Kalbach

1990, 130). In Canada as elsewhere, the barrier presented by physiognomic characteristics was particularly

difficult to cross in the process of assimilation. Chinese

and West Indians, though they favored blending into

the larger society, encountered the most problems in

doing so (Breton et al. 1990,257).

The revised immigration law (1968) as well as the

Charter of Rights and Freedoms have transformed Canadian cities. They have eliminated overt discrimination. In addition, immigrants now are by and large

better educated, often technicians and professionals

or, lately, investors and entrepreneurs. Large proportions of recent immigrants are visible minorities. Most

settle in metropolitan areas and head directly to the

suburbs. They are forming ethnic concentrations in

new parts of cities. Furthermore, the urban structure

itself is changing. Cities have spilled out to form

multi-focal metropolises. Edge cities have emerged.

These new urban forms are socially more diverse.

Bourne observes that all of the larger urban areas in

Canada except Quebec City show substantially higher

indices of diversity in 1981 than in 1971 (Bourne

1989, 319). A new social mosaic is evident in the suburbs: Agincourt in metropolitan Toronto, Vancouvers

Richmond area, and Montreals West and North Island are obvious examples of neighborhoods of the

new mosaic. Such ethnic concentrations are evident

too in edge cities like Mississauga, Brampton, Richmond Hill, and Surrey.

The social mix characteristic of the new multicul-

1

486

APA JOURNALAUTUMN 1997

turalism is also reflected in the fashionable districts of

central cities. Here clubs, bars, boutiques, gift shops,

and restaurants offering a variety of ethnic goods intermingle, serving youth, yuppies, and tourists. Even

new waterfront developments-Harbourfront, Granville Island, and Old Montreal-are hip places by virtue of the cultural diversity of their commercial

establishments. These new expressions of multiculturalism mix ethnicities to create cosmopolitan districts.

Thus, multiculturalism now serves two functions.

First, it fulfills the social needs of ethnic communities,

and, second, it weaves diversity of both activities and

built forms into urban and regional structures. These

functions bear directly on neighborhood planning,

which must mediate between the competing interests

of stability and change.

Socially, neighborhoods change continually; residents leave or die, and new households move in. Yet

neighborhoods are considered stable as long as the

change is incremental. With the movement of a new

ethnic group, a different social class, or new activities

into a neighborhood, however, the rate of change accelerates to the point that it reorganizes a local community, disturbs the social patterns, and necessitates

the realignment of neighborhood services. Multiculturalism comes to permeate an area through such a

process of change. Although the process is largely

market-based, the planning system is called upon to

intervene as different groups of residents respond to

marked change in a neighborhood.

Old residents come calling on the planning institutions to protect their interests. The new arrivals seek

fair treatment and accommodation of their needs and

preferences. Zoning challenges, public hearings, and

school board meetings become battlegrounds for

these competing groups. Neighborly spats or personal

biases often are pursued through planning hearings

and appeals. The planning system becomes an arena

not only for contesting ethnic interests, but for more

personal conflicts as well. It may or may not have the

mandate, resources, or instruments to resolve social

conflicts and fulfill the demands of divergent groups.

The systems effectiveness lies in separating public policy issues from interest group agendas. If it succeeds

in balancing competing interests fairly, it will have fulfilled its mandate. These lessons come through in the

case histories, reported in the next section.

Case Histories of Planning

Responses to Multiculturalism

Metropolitan Toronto: Agincourts Chinese M d s

Agincourt, in Scarborough, is an example of a typical Canadian planning systems response to the is-

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

sues precipitated when a racial and cultural minority

settles in an established neighborhood. Agincourt is a

neigborhood in the incorporated suburb, Scarborough, in the Greater Toronto Area. As Scarboroughs

population rose, Chinese restaurants, grocery stores,

and travel agencies opened. In 1983 a developer proposed to convert a roller skating rink into an indoor

Chinese shopping mall, the Dragon Centre. It met

opposition from the community and the local alderman due to its ethnic character, but which was expressed as concerns about design. The city council

approved the mall with modifications in parking requirements and restaurant space. The mini-mall of

32,500 sq. ft. has about 25 units, including a bank, a

large restaurant, noodle shops, a beauty salon, a grocery, a butcher, and a bakery, and electronic goods and

book stores.

From 1984 through 1987, eleven other malls, plazas or office complexes for Chinese clientele were developed. Only a few were built specifically for Chinese

businesses, but the others were in fact leased mostly

by stores dealing in Chinese goods. The malls, with

areas of 10,000-42,000 sq. ft., are typical neighborhood plazas: an L-shaped building for stores, set

across an office block enclosing a parking lot. Their

designs have to follow city guidelines. Apart from signage and decorative features, their architecture is not

distinctively Chinese; planning and design guidelines

preempted that.

All but two of the developments needed zoning

changes. Some cases needed official plan amendments,

as well, for site configurations, the mix of proposed

commercial, office or industrial uses, or parking requirements. An issue specific to Chinese commercial

use was the inclusion of large banquet halls and restaurants as mall anchors. These became symbols of the

malls Chinese character and stimulated neighborhood objections that targeted parking and congestion.

The planning department steered through these

controversies by taking a neutral stance toward users

ethnicity, supporting openness in the real estate market, and limiting planning interest to matters of physical development. The parking requirements for

restaurants were raised, and site layouts were closely

monitored in response to neighborhood concerns. The

city council was buffeted by, on the one hand, its commitment to promote development and, on the other,

by having to accommodate pressures from resistant

neighborhoods. It steered a gingerly course between

ethnic provocations and the passions about neighborhood stability versus change. By addressing specific

zoning and site plan issues and by providing a forum

for contending interests, the planning process helped

to manage neighborhood change. It did not offer a

grand physical or social design, but it worked incrementally to promote mutual adjustment.

Vancouver: Monster Homes in Kerrisdale and

South Shaughnessy

A similar strategy is evident in the case of the

Monster Homes of Vancouver. In the 1980s, Vancouver aggressively elicited capital from Hong Kong and

Taiwan. Immigrating entrepreneurs and professionals

then fueled the real estate boom, driving up housing

prices. In Kerrisdale and Shaughnessy, which are leafy

Victorian neighborhoods, Asian immigrants rebuilt

homes to suit their tastes and activities. Within the

zoning envelope, the newcomers used the permissible

coverage and setbacks to create massive and lavish

homes nicknamed Monster Homes. The long-time residents fiercely demanded that the city prohibit such

development. The controversy simmered for about

two years, often assuming ethnic overtones (Mdcleuns

1994).

The planning system had been caught by surprise,

since the new homes conformed to the regulations. A

strategy similar to that described in the Toronto example was pursued. The Mayor and the City Council

designated the neighborhoods as a special study area

and asked the Planning Department to review the

RS-1 Zoning. The Planning Department held public

hearings that brought together representatives of the

original residents and the new Asian residents to hammer out a compromise resulting in the adoption of

new (1993) design guidelines. They required builders

of homes to take into account streetscape, the architecture of adjacent homes, and the landscape. The

maximum allowable size was unchanged, but brought

under design control.

These measures diffused the public controversy,

but added about six weeks of development review to

the approval process for new homes in these neighborhoods, as compared to the three days it used to take

to get a building permit. A classic confrontation of

neighborhood change versus tradition was managed

by developing a design policy and tuning up the

zoning by-laws. Here, again, the planning process addressed mainly design concerns and steered a

middle position between contending interests. The

lesson here, too, is that planning should ensure fair

treatment and limit its interventions to mandated policy issues.

Metropolitan Toronto: Kingsview Park (The

Dixon Case)

The Dixon case, on the other hand, is an example of cultural and racial tensions arising entirely

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

/487

MOHAMMAD A. OADEER

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

from changes in the tenure mix of the housing market

and the demographic mix of the community. Here the

central question is how to reconstitute a local community after dramatic demographic changes.

A television documentary and numerous newspaper articles have made the Dixon Complex notorious

as an example of a neighborhood gone awry.

Kingsview Park is a highrise condominium complex

of six buildings containing 1,794 apartments, built in

1971 along the four-lane Dixon Road in Etobicoke,

a suburban municipality of Metropolitan Toronto.

Kingsview Park was first inhabited by young families

and empty-nesters who were mostly owner-occupants;

about half had migrated from Europe shortly after

World War 11.

Within a few years of its development, the social

composition of this complex began to change. As

young owner-occupants moved out, the vacancies

were filled by recent immigrants from Southern Europe and Asia. The proportion of renters rose steadily,

to about 12 percent in 1977.

Torontos property boom of the 1980s attracted

speculator-investors, absentee owners who rented

out apartments while waiting for capital gains. By

1989-91, 25 percent of the apartments were renteroccupied. Then, because of high vacancies and downturn in the property market, occupancy gradually

filtered down in the rental market to the Somalis who

had come in the most recent wave of immigration.

By 1994, poor Somalis occupied 59 percent of the

rental units and were 35 percent of Kingsview Parks

population. This change in the complexs tenure-mix

and social composition precipitated ethnic tensions

and cultural conflicts between white owner-occupants

and the Condominium Board, and black tenants. A series of confrontations between Somali youths and the

management and security personnel culminated in a

riot that spilled onto Dixon Road and blocked traffic

on July 30, 1993. This breakdown of the local community prompted public intervention.

The Mayor and the Municipal Council of Etobicoke responded to the riot by forming the Dixon

Road Community Response Team and the Task Force

on Residential Overcrowding. The Planning Department was represented on these bodies. The Task Force

recommended a review of security and management

in the buildings, race and cultural sensitivity training

for security personnel, and formation of residents

committees, along with other measures. The planning

issue was framed as a matter of housing occupancy:

overcrowding in rented apartments became the focal

point of the Task Force. The issue targeted mostly Somali households, which tend to be large and have long

been viewed as harboring friends and relatives.

J

488

AFA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

Conventional urban planning had no defined role

in this profound cultural clash; yet there were continual calls from one or the other parties for the planning

department to get involved despite the fact that on

these issues it had little authority. The need was for

social planning and community organization. Instead,

the proposed solutions to the Dixon Complex include regulations to discourage overcrowding and a

recommendation to amend provincial legislation to

allow municipal inspectors the authority to enter private dwelling without warrants. In short, the planning

response to this social and cultural clash was simply

to tune up property standards and create the statutory

instruments to enforce them.

These cases illustrate public issues precipitated by

the diversification of forms, functions, and populations in neighborhoods. The Canadian planning system usually muddles through such changes. It favors

neighborhood stability, but promotes development. It

has neither the authority nor the tools to intervene

forcefully in real estate markets propelled by individual choices. And, indeed, multiculturalism calls into

question current notions about stability and social

mix in neighborhoods. It adds another reason for reexamining the social assumptions of urban plans, already being questioned on other grounds. Sewell concludes that stable residential neighborhoods may not

be a good place to call home and cites conclusions of

other observers in support of his observations (Sewell

1994, 67). Social harmony and balance, rather than

stability alone, should be the guiding principle for

multicultural neighborhoods- this is the lesson from

the Dixon case.

The overarching implication of the Canadian experience is that the role of the planning system in

managing social change in neighborhoods is limited.

In particular, planning regulations cannot and should

not be based on the characteristics of clients, though

policies aiming to satisfy peoples needs do have to

apply performance measures. It follows, then, that the

planning system has not forged any systematic approach to sustain and promote cultural diversity of

neighborhoods.

Ethnic Business Enclaves

Multiculturalism also manifests itself in the commercial structure of cities, in the form of ethnic business enclaves, whether as sectoral specialization such

as Koreans dominating the flower trade or Punjabis

managing the taxi service, or spatial enclaves like the

concentration of restaurants, food stores, and dress

boutiques in Chinatown or the Greek village. Both are

distinct economic formations in which ethnic solidarity and cultural norms undergird the transactions

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

among establishments as well as among owners, managers, and workers (Portes and Bach 1985).

In Canadian cities, local businesses of ethnic

neighborhoods have been the basis of their cultural

economies. Often they have extended their markets

beyond their surrounding neighborhoods. In fact, not

all immigrant-owned businesses target ethnic populations; many serve mainstream markets. An historical

example of ethnic entrepreneurs in the mainstream

economy is seen in the Chinese eateries that Chinese

cooks who had been laid off by the Canadian Pacific

Railway started in little villages of the Prairie provinces in the late 19th century. To this day, they are the

main restaurants/hotels in small places-commercial

manifestations of the old multiculturalism.

Since the 1970s) a new and vigorous form of ethnic business enclaves has emerged in Canadian metropolitan areas. Torontos revitalized Chinatown and its

Chinese suburban malls and office clusters, its Indian

bazaars and Greek villages, and its Punjabi malls are

obvious examples. Similar clusters have emerged in

Vancouver and Montreal, and on a small scale in Calgary and Winnipeg. These enclave commercial districts serve metropolitan markets, creating a niche

in the regional economy. They have been created

through private initiatives; they were not planned or

even anticipated by planning authorities.

City planning has often come to acknowledge the

enclaves once they have been formed. Its reactive role

consists of sustaining and consolidating them, frequently in the face of some local opposition that is

expressed as concern about density and traffic, but

that has an ethnic and racial subtext. At best, the planning system takes a circumscribed view of its jurisdiction in such situations. Focusing on development

issues and regulatory requirements, it uses them as

the means for mediating among competing interests

and groups. The planning system faces a dilemma: it

cannot plan or zone by the characteristics of persons,

yet it has to acknowledge the cultural bases of an enclaves economy.

Ottawa:Somerset Heights

Ottawas Somerset Heights area, the citys hub of

multicultural commercial establishments, illustrates

the planning systems response to the formation of an

ethnic business enclave, as recounted by Marc Labelle

(1992).

Ottawa, the capital of Canada and center of a regional municipality, has been a bicultural city, though

with the French language and culture not always obvious. In the past twenty-five years, however, the city

has undergone a social and cultural transformation.

Its Francophone population has gained prominence,

and recently Italians, East Europeans, and Asians have

become a presence.

Somerset Street has evolved into the center for Ottawas ethnic businesses. Between Bay and Rochester

Streets, it has become the spine of Ottawas Chinatown or, more accurately, of a multicultural neighborhood. Its modest homes, which had declined in the

postwar period, have been revived by immigrantsItalians and Chinese at first, and more recently, Arabs,

South Asians, and Africans. Since 1971, dim sum halls,

Chinese restaurants, groceries, and gift shops have

made the area into a Chinatown. In the late 198Os,

Vietnamese businesses started to appear, and now Caribbean and Middle Eastern stores are also springing

up. The area has become a multicultural business enclave with a predominance of East Asian stores. The

story of its transformation is shown in table 2.

Over a 30-year period, 1961-1991, area businesses

increased from 60 to 101, mostly ethnic establishments. The Asian (Chinese) businesses dominated the

street after 1971, steadily increasing from about 8 percent of ethnic businesses to 81 percent in 20 years.

With the commercial transformation, the Asian population in the area has increased and a gradual gentrification of the neighborhood has occurred.

Ottawas City Planning Department responded

to the neighborhood change in the following

manner.

TABLE 2. Evolution of Okawas Somerset Heights

Ethnic Businesses No.

Year

1961

1971

1981

1991

Total N u m b e r o f Businesses

60

76

88

101

(%)

29

35

49

85

(48.0)

(46.1)

(55.6)

(84.2)

Asian Businesses No.

(as % o f Ethnic Business)

2

2

28

69

( 7.8)

( 5.7)

(57.1)

(81.2)

Source: Marc Labelle 1992. tables 7 and 8

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

/489

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

1964 Ottawa Citys comprehensive zoning bylaw

designated Somerset Heights as a General

Commercial Zone permitting commercial uses

for the ground floor and dwellings above.

1977 The Dalhousie Neighbourhood Plan designated the area for mixed land use-i.e. ground

floor commercial uses and residences above; pedestrian orientation emphasized.

1984 The citys new zoning bylaw maintained the

area as a General Commercial Zone.

1988 Somerset Street West Planning Study recommended Multicultural Village as the areas

theme, and encouraged ethnic expression and

the establishment of a Business Improvement

Area (BIA).

1989 The citys Community Improvement Plan projected streetscape improvements and other

capital works.

1992 A new official plan designated the areas as

Neighbourhood Linear Commercial, recognizing the areas distinctive character and allowing

mixed uses and pedestrian orientation.

Up to 1986, the Planning Department ignored the

cultural dimension of the neighborhood change and

maintained the fiction of uniformity. Only with the

Business Improvement Area (BIA) designation, and

consequent capital works including the development

of a Chinese community center, and signage and

streetscape in 1988, were the cultural characteristics

of the area officially acknowledged. Still, the official

plan policies have not given much weight to ethnic

commercial activities. They continue to treat the area

as Neighbourhood Linear Commercial. Multiculturalism is evident in the facilities and services developed,

but not in the citys zoning and land use policies. The

planning response has been reactive and restrained.

The case of the Scarborough shopping malls also

illustrates city plannings reactive role in such developments. Once the malls were being developed, Scarboroughs city planning department duly accommodated

them, first by resolving some contentious issues and

then by upholding developers rights in the face of

neighborhood opposition. Yet north of Scarborough,

in Markham, Chinese shopping malls have become a

lightning rod for ethnic confrontation. An intemperate remark by the deputy mayor about the excess of

Chinese malls driving away old residents has precipitated fierce public arguments about the ethnic

composition of the community (The Globe and Mail

1995b, AG).

The policy issues that ethnic enclaves bring to the

fore include the need for multilingual signage to ensure equal access, culturally sensitive services, and de-

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

sign guidelines for built forms and aesthetics that are

both diverse and harmonious. Another issue that

arises is the vulnerability of businesses to changing

tastes and demands. The demographics of ethnic business enclaves tend to shift among groups, so planning

policies should recognize the prospect of change. Supporting an enclaves special cultural character while

keeping it open to all is the key challenge for multicultural planning in commercial areas. Canadian metropolitan areas have usually accommodated business

enclaves through exceptions and variances of their

statutory plans, as numerous thriving enclaves attest.

These enclaves have, however, added a new element to

the urban commercial hierarchy, necessitating reconsideration of planning policies and standards.

Housing Choices

Multiculturalism gives rise to two issues in the

housing market. First is the question of discrimination against ethnic minorities in access to housing.

Apart from visible physiognomic difference and class,

language, cultural origin, or religion could also be the

basis for restrictive practices in the market. Post-1960s

legislation, including the Landlord-Tenants Act, has

combined with the influence on the market of demand

by ethnic minorities to eliminate overt forms of discrimination. There are cases of refusal to rent to Africans or East Indians, but they are sporadic and subject

to legal recourse. The legacy of systematic bias against

immigrants and visible minorities in the mortgage

market, local codes, and housing standards is being

exposed and eroded.

The second housing issue, more directly related to

multiculturalism, is the matter of housing choices for

ethnic minorities. Although their requirements do not

differ from mainstream norms for housing type, location, and utilities, their preferences for dwelling size,

layout, and neighborhood differ significantly. Most

immigrants want single-family homes (Clayton Research 1994), but ethnic groups differ even among

themselves in their choices of interior designs and

community facilities.

The stereotypes are that Portuguese prefer two

kitchens, Italians like large lots for gardens, and the

Chinese notion of Feng-Shui predisposes them against

houses on cul-de-sacs. Neighborhoods in proximity to

schools with language classes and to appropriate religious associations and cultural institutions are also

preferred. Immigrants of modest income may want

the option of dividing a home to create a rental apartment; their affluent counterparts prefer large homes,

for prestige as well as for prospects of gathering together the extended family. For ethnic groups, these

culturally based preferences, differing by economic

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

class, are measures of housing satisfaction. They often

fall within the purview of building, safety, and public

health codes; and of planning standards, particularly

for occupancy densities, household use, and the definition of a family. Often these do not accommodate

ethnic minorities preferences. Case studies reported

earlier, particularly the Monster Homes and the Dixon

cases, illustrate the divergence between the norms presumed to be universal and the minority groups

choices for home and family. Ironically, the very participatory procedures meant to give citizens a voice in

planning provide the convenient means for some local

groups to resist the accommodation of others divergent needs and tastes. Public hearings on planning

regulations have often been turned into the tools of

NIMBYism and ethno-racism.

The overall effect of multiculturalism is to reveal

the cultural biases embedded in the so-called universal

standards. It follows that rethinking the bases of housing standards and planning policies is necessary, not

only to accommodate divergent preferences, but also

to integrate diverse architectural and functional elements into coherent local and regional idioms. The

convenience and satisfaction of both old and new residents have to be ensured through balanced development. This is the agenda of planning from the

multicultural perspective.

Institutions and Services

Not only spatial and architectural forms, but also

social institutions and community services are affected by multiculturalism. Ethnic communities contribute new ceremonials, sports, practices, and

organizations to the public life of a locality. Most of

these institutions and services are provided privately,

but public responsibility lies in facilitating their development and in a fair distribution of public funds for

social programs. Multiculturalism requires ensuring

equal opportunities to develop mosques and temples

as well as churches; baseball diamonds and soccer

fields; Highland dance troupes and Caribbean carnivals; and language classes as well as ballet schools.

Canadas planning system is fitfully accommodating

such diversity of institutions and services. How this

institutional learning is evolving is illustrated by the

case of Islamic mosques.

Recent waves of Muslim immigrants from the

Middle East, Eastern Europe, and South Asia have necessitated the building of mosques and Islamic centers. The building of a mosque or Islamic center for a

congregation typically moves through three stages. In

the beginning, someones living room serves as the

gathering place for weekly prayers, which leads to renting a hall or buying an unused church for congrega-

tional gatherings, and finally to the stage of building

a new mosque. At each of these three stages, there are

planning issues. From the changes in the use of an existing building to the building of a new mosque, at

numerous points public approvals and planning permissions are required. Yet many existing zoning and

sire plan regulations for religious uses are based only

on the requirements of churches; therefore, mosques

have to be developed through variances to planning

standards and policies. In one case, a minaret had to

be designated as a clock tower, though once built its

function and integrity were so obvious that the local

council happily dispensed with the installation of a

mock clock. Each proposal creates a battleground reverberating with ethno/racial overtones, as proponents and opponents contend over parking standards,

lot coverage, etc.6

Yet precedents and experiences that embody the

multicultural perspective are accumulating; one by

one, thirty mosques have been established in the Toronto area. The planning system obviously is accommodating mosques, gurdwaras and temples, but

systematic policies and standards that embrace such

options have not appeared. Planners have been more

open to such developments than have their political

bosses.

A similar process is under way with the provision

of other social and cultural services. For example, varying burial customs require revisions in the regulatory

standards for cemeteries and operations of crematoriums. Other examples of services for which demands

are mounting are multilingual kindergartens, heritage

language courses, soccer or cricket fields, banquet halls

and social clubs. Many of these institutions and services require physical development, and others may

necessitate changes in the policies for public grants.

A Meals-on-Wheels service, for example, may have to

provide ethnic foods to serve a non-English/French

population appropriately. Even a service such as family

counseling has cultural dimensions. Toronto, for example, has six family and womens centers specializing

in counseling South Asian women. Similar developments are taking place wherever there are strong pressures of demand and community initiatives. From

Caribbean parades to Iranian film festivals and Yiddish poetry readings, Canadian cities support a rich

and diverse artistic and cultural life. Little by little,

cultural diversity is being acknowledged by precedents

being established in the planning system. Toronto,

Vancouver, and Montreal are leading in the development of culturally-sensitive modes of planning. Metro

Torontos Social Development Strategy recognizes

diversity and commits to nondiscrimination in the

sharing of the citys resources and opportunities.

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

1491

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

Translating these goals into policies, standards, and

practices is the challenge that remains to be met.7

Conclusion

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

In the preceding sections, we have reviewed a

range of issues arising from the multiculturalism of

Canadian cities and the planning systems responses

in dealing with them. This review suggests some general conclusions.

Multiculturalism is an expression of the social diversity in contemporary cities. The traditional

source of multiculturalism, namely immigration, is

now complemented by forces of globalization that

scramble national (cultural) boundaries and promote rapid circulation of information and people.

The diversity of lifestyles and cultures has become a

resource in post-industrial cities.

The cultural and racial diversity of populations is

raising issues of fairness in fulfilling the social needs

of groups according to their preferences. Diversity

requires that in the service of ethnic neutrality, public policies should not foster insensitivity to the systematically different needs and requirements of

diverse populations (Thomas and Krishnarayan

1994). These values necessitate, on the one hand, the

elimination of discrimination in the markets for

housing and urban facilities and services, and, on

the other, the promotion of a plurality of spatial

forms and functions to fulfill citizens needs to their

satisfaction. The effectiveness of a planning system

lies in meeting these criteria.

By and large, ethnic communities are flourishing in

Canadian cities. Overt discrimination is rare. The institutional biases are being exposed and aired. Canadian cities are strikingly diverse, vibrant, and

orderly-a far cry from their historical reputation of

being clean, safe and dull. Much of this change is

attributable to the diversity of forms and functions

emerging through market processes and individuals

initiatives. Ethnic residential concentrations have

emerged in the suburbs. Immigrants businesses are

opening new lines of production. Ethnic communities have carved out distinct artistic, cultural, and

religious lives in the cities. In short, multiculturalism is now a defining character of Canadian cities.

A Trinidad-born commentators observation sums

up the situation: In the 30 years Ive been in Canada, its cities have changed beyond what could have

been predicted. They have loosened up (Alexis 1995,

C19). Although most of these changes have come

from private initiatives, the planning system and

other public institutions can take credit for accommodating them.

The planning process is becoming more inclusive by

seeking out ethnic communities participation in

public debates. Their diverse cultures are beginning

to be acknowledged at the procedural level, and their

concerns are being aired as a part of the planning

process. Professional planners are relatively more responsive to minorities interests than is the political leadership.

The policy response to multiculturalism is still reactive and ad hoc. Even in Toronto and Vancouver, the

needs of ethnic communities are accommodated

through amendments, exceptions, or special provisions to statutory plans, policies or programs. Despite its acknowledgement as a social condition,

cultural and racial diversity is not reflected in planning policies. Planning standards and criteria continue to be based on unitary conceptions of citizens

needs. Systematic attempts to forge pluralistic visions of urban plans and programs are only haltingly emerging.

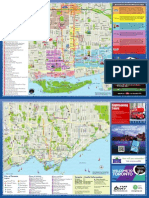

Conceptually, planning measures that accommodate

multiculturalism can range from procedural changes

and administrative adaptations to redefining the

goals and ideologies that inform policies and programs. This range of measures can be represented

as a ladder of increasingly wide-ranging and general

principles of planning (figure 1).

7 A multicultural vision o f the development strategy for a city or region

6

Cultural and racial differences reflected in planning policies and acknowledged as bases for equitable treatment

Provision o f specific public facilities and services for ethnic communities

Special District designation for ethnic neighborhoods and business enclaves

3 Accommodation o f diverse needs through amendments and exceptions, case by case

2

lnclusionary Planning Process-participation by and representation o f multicultural groups on planning committees

Facilitating access by diverse communities t o the planning department

FIGURE 1.

J

492

A ladder of planning principles supporting multiculturalism

APA J0URNAL.AUTUMN 1997

PLURALISTIC PLANNING FOR MULTICULTURAL CITIES

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

The Canadian planning system has largely reached

level 3 in responding to multiculturalism of its metropolitan areas, and levels 4 and 5, in part, in Toronto

and Vancouver. The pluralism of planning approaches

is gradually emerging. Yet it raises many critical questions about the philosophy and substance of planning

that have not been addressed.

What does the multicultural vision for a city or region mean? It has an aura of post-modernism about

it, architecturally as well as functionally. It diverges

from the uniformity of modernist practice (Savage

and Warde 1993,139), envisioninginstead a contemporary city that harmonizes distinctive aesthetics,

structures, and practices. Forging such a vision and

translating it into policies, programs, and standards

defines the scope of multicultural planning-a diversity of policies and programs that goes beyond simply advocacy for the disadvantaged.

To meet the diverse needs of a multitude of communities, planning policies and programs should be

modified in two ways: (a) to make specific provisions

for the religious and cultural facilities of significant

ethnic groups, and (b) to formulate performancebased criteria for the provision of common facilities

and services, i.e. schools, parks, welfare, etc. The

fairness of planning policies is to be judged by the

comparability of outcomes rather than by the mechanical uniformity of approach.

The recognition of ethnic and social diversity calls

for flexibility in planning norms and practices. At

the same time, projecting some degree of certainty of

outcomes is essential for effective and accountable

planning. Thus a balance of certainty and flexibility

is another requirement necessitated by multiculturalism. Probably an inclusive planning process can

provide the necessary certainty and consistency,

while performance-based standards and criteria can

assure a reasonable level of flexibility.

Multiculturalism also raises the issue of social integration versus segregation. The lesson learned so far

in this regard is that involuntary segregation or prescriptive ghettoization is both illegal and immoral;

but planning that provides choices for individuals

and groups to attain a livable environment through

the diversity of forms and facilities is desirable. The

concentration of one or another group in an area by

choice is within the scope of public values as long as

others are not systematically excluded. Freedom of

choice is the defining value for public policy.

To conclude, multiculturalism in planning is preeminently a matter of awareness of race and culture

among planners and public officials. A good starting

point for promoting pluralism in the planning sys-

tem will be to entrench the Human Rights Code in

planning policies and programs and to make cultural and racial discrimination a legitimate basis for

planning appeals. Equally important will be employment equity and the representation of minorities on

public bodies.

AUTHORS NOTE

The research for this article was funded by a grant from the

Ministry of State Multiculturalism and Citizenship Canada.

The financial support is gratefully acknowledged. The research for the Vancouver case study was performed by Kim

Flick, and that for the Dixon Complex by Kelly Grover. The

source for the Ottawa case study is Marc Labelle, Ethnic Businesses as Instrument ofDeuelopment (Masters Report, School of

Urban and Regional Planning, Queens University, Canada).

Jackie Bells editorial assistance has helped clarify many

ideas. The views expressed here, however, are entirely the authors responsibility.

1. The awareness of race and class differences and their

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

bearing on policies and programs is longstanding. Cultural, religious, gender, and lifestyle differences are beginning to be recognized.

The Canadian planning system is hierarchical and autonomous, centered in provinces. By and large, provincial ministries hold the authority to approve local and

regional plans, define their scope and jurisdiction, lay

down priorities, oversee procedures, and initiate housing and community service programs. Similarly, provincially appointed boards are the appellate bodies, and

often provincial ministers are the final arbiters in contentious matters. Municipalities prepare, adopt, and

enforce statutory plans, development policies, and standards under provincial legislation and delegated authority. This is a barebones description of the planning

system in Canada.

Rawls postulates two principles of justice: (1) equal

rights of each person to basic liberties, and (2) the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged consistent with the

just savings principle (Rawls 1971,302-3). Equity Planning refers to the planning approach that explicitly aims

at improving the welfare of the disadvantaged (Krumholz 1982). Pareto Optimality is an economic decision

criterion.

In this article, our primary focus is on the multiculturalism of immigrants, old and new. Planning issues relating to aboriginal communities are not discussed,

because they are a topic by themselves.

In Canada, there has been a consistent stream of opinion directed against multiculturalism. See Bibby 1990

and Bissoondath 1994.

The proposal for a mosque in East York ran into opposition from the City Council and the neighborhood

Cypriot-Greek community center. Although the Council

APA JOURNALmAUTUMN 1997

1493

MOHAMMAD A. QADEER

narrowly approved the proposal, the parking requirements have been interpreted in such a way that the development remains in limbo. See the Toronto Star 1995.

7. A vast chasm persists between goals and policies even in

those jurisdictions that proclaim promotion of diversity

and acknowledgement of multiculturalism as their

planning goals. The City (not Metro) of Torontos official plan process defined facilitating and accommodating cultural diversity as its goal, but the draft plan has

no policies explicitly addressed to this goal. Similarly,

Vancouvers City Plan has no specific policies addressing

ethnic and cultural aspects of neighborhoods. After an

inclusive planning process, the Plan has shied away

from dealing with ethnic issues.

Downloaded by [Vancouver Island University] at 21:55 26 September 2015

REFERENCES

Alexis, Andrt. 1995. Taking a Swipe at Canada. The Globe and

Mail, January 7, 1995.

Artibise, Alan F.J. 1977. Divided City: The Immigrant in

Winnipeg Society, 1879-1921. In The Canadian City, edited

by Gilbert A. Stelter and Alan F.J. Artibise. Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart.

Badets, Jane. 1993. Canadas Immigrants: Recent Trends. Canadian Social Trends (summer): 8-11.

Bibby, Reginald W. 1990. Mosaic Madness: The Potentialand Poverty of Canadian Life. Toronto: Stoddart.

Bissoondath, Neil. 1994. Selling Illusions. Toronto: Penguin.

Bourne, Larry. 1989. Are New Urban Forms Emerging? Empirical Tests by Canadian Urban Areas. The Canadian Geographer 33,4 312-28.

Breton, Raymond, Wsevolod Isajiw, Warren Kalbach, and Jeffrey Reitz. 1990. Ethnic Identity and Equality. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

City of Toronto Planning and Development Department.

1991. City Plan: The Citizens Guide. The Official Plan Proposal Report.

City of Vancouver. 1993a. City Plan Tool Kit. Vancouver, B.C.

City of Vancouver. 1993b. Ideas Book. Vancouver, B.C.

Clayton Research Associates. 1994. Immigrant Housing Choices,

1986. Ottawa: Research Division, Canada Mortgage and

Housing Corporation.

Davidoff, Paul. 1965. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning.

Journal of the American Institute ofplanners 31,4 331-8.

Elder, Phil. S., and Janet M. Keeping. 1986. The Charter of

k g h t s and Community Planning. Pkm Canada 26,s: 210.

Fleras, Augie, and Jean L. Elliott. 1992. Multiculturalism in

Canada. Scarborough: Nelson Canada.

Gans, Herbert J. 1961. The Balanced Community: Homogeneity or Heterogeneity in Residential Areas? Journal of the

American Institute of Planners 26, 3: 6.

Globe and Mail. 1995a. November 17, 1995: A10.

Globe and Mail. 1995b. August 23, 1995: AG.

Harney, Robert F. 1985. Ethnicity and Neighbourhoods. In

Gathering Place: Peoples and Neighbourhoods of Toronto, 1934-

i

494

APA JOUFAL.AUTUMN 1997

1945, edited by Robert F. Harney. Toronto: Multicultural

History Society of Ontario.

Hayward, Victoria. 1922. Romantic Canada. Toronto: MacMilIan & Co.

House of Commons. 1971. Statement by the Prime Minister. Ottawa, October 8, 1971.

Kalbach, Warren. 1990. Ethnic Residential Segregation and

its Significance for the Individual in an Urban Setting. In

Ethnic Identity and Equdity, edited by Raymond Breton and

Wsevolod W. Isajiw et al. Toronto: University of Toronto

Press.

Krishnarayan, Vijay, and Huw Thomas. 1993. Ethnic Minorities

and the Planning System. The Royal Town Planning Institute.

Krumholz, Norman. 1982. A Retrospective View of Equity

Planning: Cleveland 1969-79. Journal of the American Planning Association 48,2: 163-78.

Krumholz, Norman. 1994. Advocacy Planning: Can It Move

the Center? Journal of the American Planning Association

60,2: 150-1.

Labelle, Marc. 1992. Ethlzic Businesses as Instrument of Development. A Masters Report submitted to the School of Urban

and Regional Planning, Queens University, Canada.

McLeans. 1994. Weekly Feb. 7, 1994.

Mitchell, Katharyne. 1993. Multiculturalism, or the United

Colors of Capitalism? Antipode 25,4: 263-94.

Moghaddam, Fathali M. 1994. Ethnic Segregation in a

Multicultural Society. In The Changing Canadian Metropolis:

A Public Policy Perspective, Vol. one, edited by Frances

Frisken. Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies

Press, University of California.

Muller, Thomas. 1993. Immigrants and the American City. New

York: New York University Press.

Multicukurahm and Citizenship Canada. 1991. Multiculturalism: What Is It About? 0ttawa.

Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto. Undated. New Realities: New Directions, A Social Development Strategy f i r Metropolitan Toronto. Toronto.

Porter, John. 1965. The VerticalMosaic. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press.

Portes, Alajandro, and Robert L. Bach. 1985. Latin Journey.

Berkeley: University of California.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory ofJustice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Reitz, Jeffery G. 1980. The Survival of Ethnic Groups. Toronto:

McGraw-Hill.

Savage, Mike, and Alan Warde. 1993. Urban Sociology, Capitalism and Modernity. Hampshire: MacMillan.

Sewell, John. 1994. Houses and Homes. Toronto: James Larimer and Co.

Thomas, Huw, and Vijay Krishnarayan. 1994. Race Disadvantage, and Policy Processes in British Planning. Environmentand PlanningA, 26: 1891-1910.

Toronto Star. 1995. Why a Proposed Mosque Stirred Up a

Hornets Nest. October 8: F4.

You might also like

- The Multicultural City As Planners' Enigma PDFDocument17 pagesThe Multicultural City As Planners' Enigma PDFTed Hou YuanNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities For Planning in PDFDocument7 pagesChallenges and Opportunities For Planning in PDFTed Hou YuanNo ratings yet

- Why Community Land Trusts?: The Philosophy Behind an Unconventional Form of TenureFrom EverandWhy Community Land Trusts?: The Philosophy Behind an Unconventional Form of TenureNo ratings yet

- Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First-Century AtlantaFrom EverandRed Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First-Century AtlantaNo ratings yet