Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 Heinz Case Study

Uploaded by

sachin2727Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 Heinz Case Study

Uploaded by

sachin2727Copyright:

Available Formats

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

UV5147

Rev. May 13, 2015

H. J. HEINZ: ESTIMATING THE COST OF CAPITAL IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

To do a common thing uncommonly well brings success.

H. J. Heinz Founder Henry John Heinz

As a financial analyst at the H. J. Heinz Company (Heinz) in its North American

Consumer Products division, Solomon Sheppard, together with his co-workers, reviewed

investment proposals involving a wide range of food products. Most discussions in his office

focused on the potential performance of new products and reasonableness of cash flow

projections. But as the company finished its 2010 fiscal year at the end of Aprilwith financial

markets still in turmoil from the onset of the recession that started at the end of 2007the

central topic of discussion was the companys weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

At the time, there were three reasons the cost of capital was a subject of controversy.

First, Heinzs stock price had just finished a two-year roller coaster ride: Its fiscal year-end stock

price dropped from $47 in 2008 to $34 in 2009, then rose back to $47 in 2010, and a vigorous

debate ensued as to whether the weights in a cost of capital calculation should be updated to

reflect these changes as they occurred. Second, interest rates remained quite lowunusually so

for longer-term bond rates; there was concern that updating the cost of capital to reflect these

new rates would lower the cost of capital and therefore bias in favor of accepting projects. Third,

there was a strong sense that, as a result of the recent financial meltdown, the appetite for risk in

the market had changed, but there was no consensus as to whether this should affect the cost of

capital of the company and, if so, how.

When Sheppard arrived at work on the first of May, he found himself at the very center

of that debate. Moments after his arrival, Sheppards immediate supervisor asked him to provide

a recommendation for a WACC to be used by the North American Consumer Products division.

Recognizing its importance to capital budgeting decisions in the firm, he vowed to do an

uncommonly good job with this analysis, gathered the most recent data readily available, and

began to grind the numbers.

This case was prepared by Associate Professor Marc L. Lipson. It was written as a basis for class discussion rather

than to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright 2010 by the University

of Virginia Darden School Foundation, Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved. To order copies, send an e-mail to

sales@dardenbusinesspublishing.com. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwisewithout the permission of the Darden School Foundation.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-2-

UV5147

Heinz and the Food Industry

In 1869, Henry John Heinz launched a food company by making horseradish from his

mothers recipe. As the story goes, Heinz was traveling on a train when he saw a sign advertising

21 styles of shoes, which he thought was clever. Since 57 was his lucky number, the

entrepreneur began using the slogan 57 Varieties in his advertising. By 2010, the company he

eventually founded had become a food giant, with $10 billion in revenues and 29,600 employees

around the globe.

Heinz manufactured products in three categories: Ketchup and Sauces, Meals and

Snacks, and Infant Nutrition. Heinzs strategy was to be a leader in each product segment and

develop a portfolio of iconic brands. The firm estimated that 150 of the companys brands held

either the number one or number two position in their respective target markets.1 The famous

Heinz Ketchup, with sales of $1.5 billion a year or 650 million bottles sold, was still the

undisputed world leader. Other well-known brands included Weight Watchers (a leader in

dietary products), Heinz Beans (in 2010, the brand sold over 1.5 million cans a day in Britain,

the biggest bean-eating nation in the world), and Plasmon (the gold standard of infant food in

the Italian market).2 Well-known brands remained the core of the business with the top 15 brands

accounting for about 70% of revenues, and each generating over $100 million in sales.

Heinz was a global powerhouse. It operated in over 200 countries. The company was

organized into business segments based primarily on region: North American Consumer

Products, U.S. Foodservice, Europe, Asia Pacific, and Rest of World. About 60% of revenues

were from outside the United States and the North American Consumer Products and Europe

segments were of comparable size. Increasingly, the company was focusing on emerging

markets, which had generated 30% of recent growth and comprised 15% of total sales.

The most prominent global food companies based in the United States included Kraft

Foods, the largest U.S.-based food and beverage company; Campbell Soup Company, the iconic

canned food maker; and Del Monte Foods, one of largest producers and distributers of premiumquality branded food and pet products focused on the U.S. market (and a former Heinz

subsidiary). Heinz also competed with a number of other global players such as Nestl, the world

leader in sales, and Unilever, the British-Dutch consumer goods conglomerate.

Recent Performance

With the continued uncertainty regarding any economic recovery and deep concerns

about job growth over the previous two years, consumers had begun to focus on value in their

purchases and to eat more frequently at home. This proved a benefit for those companies

providing food products and motivated many top food producers and distributors to focus on

H. J. Heinz Corporate Profile, http://www.heinz.com/our-company/press-room.aspx (accessed Sep. 27,

2010).

2

http://www.heinz.com/our-company/press-room.aspx.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-3-

UV5147

core brands. As a result, Heinz had done well in both 2009 and 2010, with positive sales growth

and profits above the 2008 level both years, although 2010 profits were lower than those in 2009.

These results were particularly striking since a surge in the price of corn syrup and an increase in

the cost of packaging had necessitated price increases for most of its products. Overseas sales

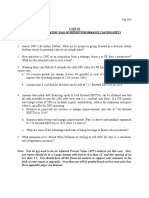

growth, particularly in Asia, had also positively affected the companys operations. Exhibit 1

and Exhibit 2 present financial results for the years 2008, 2009, and 2010.

The relation between food company stock prices and the economy was complicated. In

general, the performance of a food products company was not extremely sensitive to market

conditions and might even benefit from market uncertainty. This was clear to Heinz CFO Art

Winkelblack, who in early 2009 had remarked, Im sure glad were selling food and not

washing machines or cars. People are coming home to Heinz.3 Still an exceptionally prolonged

struggle or another extreme market decline could drive more consumers to the private-label

brands that represented a step down from the Heinz brands. While a double-dip recession seemed

less likely in mid-2010, it was clear the economy continued to struggle, and this put pressure on

margins.

While the stock price for Heinz had been initially unaffected by adverse changes in the

economy and did not decline with the market, starting in the third quarter of 2008, Heinzs stock

price began tracking the markets movement quite closely. Figure 1 plots the Heinz stock price

against the S&P Index (normalized to match Heinzs stock price at the start of the 2005 fiscal

year). The low stock price at the start of 2009 had been characterized by some as an overreaction and, even with the subsequent recovery, it was considered undervalued by some.4

Figure 1. Heinz stock price and normalized S&P 500 Index.

55

50

45

40

35

Price

30

Index

25

20

15

5/2/2005

5/2/2006

5/2/2007

5/2/2008

5/2/2009

Data sources: S&P 500 and Yahoo! Finance.

Andrew Bary, The Return of the Ketchup Kid, Barrons, January 26, 2009.

Bary; the same article noted that Heinz had an above-average portfolio of brands, led by its commanding

global ketchup franchise and, even at January 2009 prices, could be a takeover target.

4

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-4-

UV5147

Cost of Capital Considerations

Recessions certainly could wreak havoc on financial markets. Given that the recent

downturn had been largely precipitated by turmoil in the capital markets, it was not surprising

that the interest rate picture at the time was unusual. Exhibit 3 presents information on interest

rate yields. As of April 2010, short-term government rates and even commercial paper for those

companies that could issue it were at strikingly low levels. Even long-term rates, which were

typically less volatile, were low by historic standards. Credit spreads, which had drifted upwards

during 2008 and jumped upwards during 2009, had settled down but were still somewhat high by

historic standards. Interestingly, the low level of long-term rates had more than offset the rise in

credit spreads, and borrowers with access to debt markets had low borrowing costs.

Sheppard gathered some market data related to Heinz (also shown in Exhibit 3). He

easily obtained historic stock price data. Most sources he accessed estimated the companys beta

using the previous five years of data at about 0.62.5 Sheppard obtained prices for two bonds he

considered representative of the companys outstanding borrowings: a note due in 2032 and a

note due in 2012. Heinz had regularly accessed the commercial paper market in the past, but that

market had recently dried up. Fortunately, the company had other sources for short-term

borrowing and Sheppard estimated these funds cost about 1.20%.

What most surprised Sheppard was the diversity of opinions he obtained regarding the

market risk premium. Integral to calculating the required return on a companys equity using the

capital asset pricing model, this rate reflected the incremental return an investor required for

investing in a broad market index of stocks rather than a riskless bond. When measured over

long periods of time, the average premium had been about 7.5%.6 But when measured over

shorter time periods, the premium varied greatly; recently the premium had been closer to 6.0%

and by some measures even lower. Most striking were the results of a survey of CFOs indicating

that expectations were for an even lower premium in the near futureclose to 5.0%. On the

other hand, some asserted that market conditions in 2010 only made sense if a much higher

premiumsomething close to 8%were assumed.

As Sheppard prepared for his cost of capital analysis and recommendation, he obtained

recent representative data for Heinzs three major U.S. competitors (Exhibit 4). This information

would allow Sheppard to generate cost-of-capital estimates for these competitors as well as for

Heinz. Arguably, if market conditions for Heinz were unusual at the time, the results for

competitors could be more representative for other companies in the industry. At the very least,

Sheppard knew he would be more comfortable with his recommendation if it were aligned with

what he believed was appropriate for the companys major competitors.

5

Sheppard was sufficiently curious as to whether this number was still relevant that he calculated his own

estimated of beta from the last year of daily returns. His estimate was 0.54, close to the five-year estimate but still

notably lower.

6

After some research, Sheppard was confident that the appropriate rate was the arithmetic mean (simple

average) of past annual returns rather than the geometric mean in this context. The reason was that the arithmetic

mean appropriately calculates the present value of a distribution of future cash flows.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-5-

UV5147

Exhibit 1

H. J. HEINZ: ESTIMATING THE COST OF CAPITAL IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

Income Statement

(numbers in thousands except per-share amounts; fiscal year-end in April)

Revenue

Costs of goods sold

Gross profit

2008

9,885,556

6,233,420

3,652,136

2009

10,011,331

6,442,075

3,569,256

2010

10,494,983

6,700,677

3,794,306

SG&A expense

Operating income

2,081,801

1,570,335

2,066,810

1,502,446

2,235,078

1,559,228

Interest expense

Other income (expense)

Income before taxes

323,289

(16,283)

1,230,763

275,485

92,922

1,319,883

250,574

(18,200)

1,290,454

Income taxes

Net income after taxes

372,587

858,176

375,483

944,400

358,514

931,940

Adjustments to net income

Net income

(13,251)

844,925

(21,328)

923,072

(67,048)

864,892

2.61

1.52

2.89

1.66

2.71

1.68

Diluted EPS

Dividends per share

Data source: H. J. Heinz SEC filings, 200810.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-6-

UV5147

Exhibit 2

H. J. HEINZ: ESTIMATING THE COST OF CAPITAL IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

Balance Sheet

(numbers in thousands except per-share amounts; fiscal year-end in April)

2008

617,687

1,161,481

1,378,216

168,182

3,325,566

2009

373,145

1,171,797

1,237,613

162,466

2,945,021

2010

483,253

1,045,338

1,249,127

273,407

3,051,125

2,104,713

5,134,764

10,565,043

1,978,302

4,740,861

9,664,184

2,091,796

4,932,790

10,075,711

Accounts payable

Short-term debt

Current portion of long-term debt

Other current liabilities

Total current liabilities

1,247,479

124,290

328,418

969,873

2,670,060

1,113,307

61,297

4,341

883,901

2,062,846

1,129,514

43,853

15,167

986,825

2,175,359

Long-term debt

Other noncurrent liabilities

4,730,946

1,276,217

6,007,163

5,076,186

1,246,047

6,322,233

4,559,152

1,392,704

5,951,856

Equity

Total liabilities and equity

1,887,820

10,565,043

1,279,105

9,664,184

1,948,496

10,075,711

311.45

314.86

317.69

Cash

Net receivables

Inventories

Other current assets

Total current assets

Net fixed assets

Other noncurrent assets

Total assets

Shares outstanding (in millions)

Data source: H. J. Heinz SEC filings, 200810.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-7-

UV5147

Exhibit 3

H. J. HEINZ: ESTIMATING THE COST OF CAPITAL IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

Capital Market Data

(yields and prices as of the last trading day in April of the year indicated)

Average Historic Yields

1-year

5-year

10-year

30-year1

Moodys Aaa

Moodys Baa

3-month commercial

paper

2003

1.22%

2.85%

3.89%

4.79%

5.53%

6.65%

2004

1.55%

3.63%

4.53%

5.31%

5.87%

6.58%

2005

3.33%

3.90%

4.21%

4.61%

5.21%

5.97%

2006

4.98%

4.92%

5.07%

5.17%

5.95%

6.74%

2007

4.89%

4.51%

4.63%

4.89%

5.40%

6.31%

2008

1.85%

3.03%

3.77%

4.49%

5.51%

6.87%

2009

0.49%

2.02%

3.16%

4.05%

5.45%

8.24%

2010

0.41%

2.43%

3.69%

4.53%

5.13%

6.07%

1.21%

1.08%

2.97%

4.90%

5.22%

1.91%

0.22%

0.24%

2009

$34.42

91.4

116.5

2010

$46.87

116.9

113.7

Heinz Capital Market Prices of Typical Issues

Heinz stock price

Bond price: 6.750% coupon, semiannual bond due 3/15/32 (BBB rated)

Bond price: 6.625% coupon, semiannual bond due 10/15/12 (BBB rated)

Note that bond data were slightly modified for teaching purposes.

Data sources: Federal Reserve, Yahoo! Finance, Morningstar, and case writer estimates.

The 20-year yield is used for 200305, when the 30-year was not issued.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

For the exclusive use of R. Terpstra, 2015.

-8-

UV5147

Exhibit 4

H. J. HEINZ: ESTIMATING THE COST OF CAPITAL IN UNCERTAIN TIMES

Comparable Firm Data

Kraft

Campbell

Soup

Del

Monte

Financial Summary

Revenues (millions of dollars)

Book value of equity (millions of dollars)

Book value of debt (millions of dollars)

40,386

25,972

18,990

7,589

728

2,624

3,739

1,827

1,290

Market Data

Beta

Shares outstanding (millions)

Share price (dollars as of close April 30, 2010)

Typical Standard & Poors bond rating

Representative yield on long-term debt

0.58

1,735

29.90

BBB

5.12%

0.32

363

35.64

A

4.36%

0.72

182

15.11

BB

6.19%

Data sources: Yahoo! Finance, H. J. Heinz SEC filings, 200810; case writer estimates; Morningstar.

This document is authorized for use only by Robert Terpstra in 2015.

You might also like

- Case StudyDocument10 pagesCase StudyEvelyn VillafrancaNo ratings yet

- H J Heinz Merger and Diversification Offer Growth Opportunities in A Difficult Market 29803 PDFDocument23 pagesH J Heinz Merger and Diversification Offer Growth Opportunities in A Difficult Market 29803 PDFarpitNo ratings yet

- HeinzDocument4 pagesHeinzShubham Ranka100% (1)

- MGT431 - Apple, Einhorn, iPrefs Group ReportDocument13 pagesMGT431 - Apple, Einhorn, iPrefs Group ReportMokshNo ratings yet

- Apple Cash Case StudyDocument2 pagesApple Cash Case StudyJanice JingNo ratings yet

- H. J. Heinz M&A: Case SynopsisDocument8 pagesH. J. Heinz M&A: Case SynopsisTanya Raj100% (1)

- Concerns with DCF analysis for Intermediate Chemicals Group projectDocument2 pagesConcerns with DCF analysis for Intermediate Chemicals Group projectJia LeNo ratings yet

- Session 10 Simulation Questions PDFDocument6 pagesSession 10 Simulation Questions PDFVAIBHAV WADHWA0% (1)

- JetBlue SASB Sustainability LeadershipDocument1 pageJetBlue SASB Sustainability LeadershipShivani KarkeraNo ratings yet

- H. J. Heinz M&A: Case SynopsisDocument8 pagesH. J. Heinz M&A: Case SynopsisIA M.No ratings yet

- H.J. Heinz WACC Analysis and AssumptionsDocument5 pagesH.J. Heinz WACC Analysis and Assumptionsvenom_ftw100% (1)

- Case Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileDocument4 pagesCase Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileSubrata BasakNo ratings yet

- Heinz Case SolutionDocument4 pagesHeinz Case SolutionNischal Upreti0% (2)

- Sealed Air Corp Case Write Up PDFDocument3 pagesSealed Air Corp Case Write Up PDFRamjiNo ratings yet

- Case 01 (DSP Final)Document46 pagesCase 01 (DSP Final)2rmj100% (5)

- ACFINA2 Case Study HanssonDocument11 pagesACFINA2 Case Study HanssonGemar Singian50% (2)

- Padgett Paper Products Case StudyDocument7 pagesPadgett Paper Products Case StudyDavey FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Deluxe Corporation Case StudyDocument3 pagesDeluxe Corporation Case StudyHEM BANSALNo ratings yet

- Boeing's New 7E7 AircraftDocument10 pagesBoeing's New 7E7 AircraftTommy Suryo100% (1)

- Firm ValuationDocument7 pagesFirm ValuationShahadat Hossain50% (2)

- Bank Merger Synergy Valuation and Accretion Dilution AnalysisDocument2 pagesBank Merger Synergy Valuation and Accretion Dilution Analysisalok_samal_250% (2)

- Williams CEO evaluates $900M financing offer and long-term strategyDocument1 pageWilliams CEO evaluates $900M financing offer and long-term strategyYun Clare Yang0% (1)

- This Study Resource Was: Individial Case Analysis of AraucoDocument6 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Individial Case Analysis of AraucofereNo ratings yet

- SIEMENSDocument7 pagesSIEMENSGian Carlos Avila100% (1)

- This Study Resource Was: Group 9 - M&M Pizza Case StudyDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Group 9 - M&M Pizza Case StudyAsma AyedNo ratings yet

- Apache Case Study Analysis of Risk Management TechniquesDocument14 pagesApache Case Study Analysis of Risk Management TechniquesSreenandan NambiarNo ratings yet

- Roche S Acquisition of GenentechDocument34 pagesRoche S Acquisition of GenentechPradipkumar UmdaleNo ratings yet

- Bayer-Monsanto Deal AnalysisDocument4 pagesBayer-Monsanto Deal AnalysisAHMED MOHAMMED SADAQAT PGP 2018-20 Batch0% (1)

- Choosing The Optimal Capital Structure-Example Chapter 16Document33 pagesChoosing The Optimal Capital Structure-Example Chapter 16Shresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Case Study - AlphabetDocument4 pagesCase Study - AlphabetZan Linn HtikeNo ratings yet

- Cartwright Lumber CompanyDocument6 pagesCartwright Lumber Companykiki0% (2)

- Deutsche Brauerei CaseDocument2 pagesDeutsche Brauerei CaseIrma Martinez100% (1)

- Toy World - ExhibitsDocument9 pagesToy World - Exhibitsakhilkrishnan007No ratings yet

- Kmart, Sears and ESLDocument10 pagesKmart, Sears and ESLshreesti11290No ratings yet

- Buckeye Bank CaseDocument7 pagesBuckeye Bank CasePulkit Mathur0% (2)

- Rosario Acero SA Case StudyDocument12 pagesRosario Acero SA Case Study__myself100% (1)

- LinearDocument6 pagesLinearjackedup211No ratings yet

- Tpccaseanalysisver04 130720110742 Phpapp01Document17 pagesTpccaseanalysisver04 130720110742 Phpapp01yis_loveNo ratings yet

- Arcadian Business CaseDocument20 pagesArcadian Business CaseHeniNo ratings yet

- Gillette Company: Pressure To ChangeDocument19 pagesGillette Company: Pressure To ChangeTinakhaladze100% (8)

- Marriott CorporationDocument8 pagesMarriott CorporationtarunNo ratings yet

- Calculating AHC's Cost of Capital Using CAPMDocument9 pagesCalculating AHC's Cost of Capital Using CAPMElaineKongNo ratings yet

- Krispy Naturals Case WriteupDocument13 pagesKrispy Naturals Case WriteupVivek Anandan100% (3)

- DuPont QuestionsDocument1 pageDuPont QuestionssandykakaNo ratings yet

- Burton SensorsDocument4 pagesBurton SensorsAbhishek BaratamNo ratings yet

- Mergers & AcquisitionsDocument2 pagesMergers & AcquisitionsRashleen AroraNo ratings yet

- Appendix VI: Hertz Corp. Case Study: Overview: The Hertz Buyout Is One of The Largest Private Equity Deals. ItDocument5 pagesAppendix VI: Hertz Corp. Case Study: Overview: The Hertz Buyout Is One of The Largest Private Equity Deals. ItProutNo ratings yet

- Debt and Policy Value CaseDocument6 pagesDebt and Policy Value CaseUche Mba100% (2)

- KKTiwari - 18214263 - Worldwide Paper Company-2016Document5 pagesKKTiwari - 18214263 - Worldwide Paper Company-2016KritikaPandeyNo ratings yet

- Anandam Manufacturing CompanyDocument9 pagesAnandam Manufacturing CompanyAijaz AslamNo ratings yet

- Mattel Toy Recall Case Study: Product Safety Issues and Cultural DynamicsDocument20 pagesMattel Toy Recall Case Study: Product Safety Issues and Cultural DynamicsTariq ZebNo ratings yet

- Heinz SWOT PEST Five Forces AnalysisDocument14 pagesHeinz SWOT PEST Five Forces AnalysisTM0% (1)

- H.J. Heinz Inc - Industry Analysis - Kasey FeigenbaumDocument31 pagesH.J. Heinz Inc - Industry Analysis - Kasey Feigenbaumgreatmaratha50% (2)

- Kraft Heinz SwotDocument9 pagesKraft Heinz SwotnaveenNo ratings yet

- H.J. Heinz Inc: Industry Analysis 1Document31 pagesH.J. Heinz Inc: Industry Analysis 1Diana SorminNo ratings yet

- Kraft & HeinzDocument24 pagesKraft & HeinzAbuyousuf shagor50% (2)

- Case - HeinzDocument7 pagesCase - HeinzPilly PhamNo ratings yet

- International Management ResearchDocument5 pagesInternational Management ResearchNada AlhenyNo ratings yet

- Part 4Document13 pagesPart 4Shuo LuNo ratings yet

- H.J. Heinz Company by Maryanne M. RouseDocument6 pagesH.J. Heinz Company by Maryanne M. RouseEvelyn VillafrancaNo ratings yet

- AnnualReport 20220712115723815Document168 pagesAnnualReport 20220712115723815sachin2727No ratings yet

- Investing Under UncerDocument43 pagesInvesting Under Uncersachin2727No ratings yet

- Segment Percentage of Revenue Percentage of Profit: Share Price ChartDocument3 pagesSegment Percentage of Revenue Percentage of Profit: Share Price Chartsachin2727No ratings yet

- Mens Wearhouse 10 K Annual ReportDocument128 pagesMens Wearhouse 10 K Annual Reportsachin2727No ratings yet

- Financial Assign 4Document1 pageFinancial Assign 4sachin2727No ratings yet

- Fine Organics - Niche Products, Niche ValuationsDocument26 pagesFine Organics - Niche Products, Niche Valuationssachin2727No ratings yet

- q4 Financials ZeeDocument1 pageq4 Financials Zeesachin2727No ratings yet

- Mens Wearhouse 10 K Annual ReportDocument128 pagesMens Wearhouse 10 K Annual Reportsachin2727No ratings yet

- Uniply IndustriesDocument3 pagesUniply Industriessachin2727100% (1)

- 7 MGMT of Working CapitalDocument108 pages7 MGMT of Working Capitalsachin2727No ratings yet

- 1 Corporate Finance Assignment 2Document6 pages1 Corporate Finance Assignment 2sachin2727No ratings yet

- 1 Corporate Finance Assignment 2Document6 pages1 Corporate Finance Assignment 2sachin2727No ratings yet

- Accounting 141 Budgeting For A ManufacturerDocument18 pagesAccounting 141 Budgeting For A Manufacturersachin27270% (2)

- CAREFULLY READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE USING ASSET DEPRECIATION SHEETDocument4 pagesCAREFULLY READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE USING ASSET DEPRECIATION SHEETsachin2727No ratings yet

- ICICI D Muhurat Picks 2015Document9 pagesICICI D Muhurat Picks 2015sachin2727No ratings yet

- Four-Column Proof of Cash for Sugar and SpiceDocument2 pagesFour-Column Proof of Cash for Sugar and Spicesachin2727No ratings yet

- 1 Module 2 SLP QuestionDocument3 pages1 Module 2 SLP Questionsachin2727No ratings yet

- LLLKLKLDocument1 pageLLLKLKLsachin2727No ratings yet

- Finance HWDocument10 pagesFinance HWsachin2727No ratings yet

- 52 Techniques For Finding FraudDocument2 pages52 Techniques For Finding Fraudsachin2727No ratings yet

- Wacc NTDocument41 pagesWacc NTsachin2727No ratings yet

- 1 Usd-EuroDocument1 page1 Usd-Eurosachin2727No ratings yet

- CaseDocument7 pagesCasesachin2727No ratings yet

- 1 Acc-ExamDocument10 pages1 Acc-Examsachin2727No ratings yet

- Case 1 Please Answer ALL Question Below. Show Step by Step AnswerDocument7 pagesCase 1 Please Answer ALL Question Below. Show Step by Step Answersachin2727No ratings yet

- Mid TermDocument28 pagesMid Termsachin2727No ratings yet

- Apple Ratio FileDocument3 pagesApple Ratio Filesachin2727No ratings yet

- Bank Transfer ProblemDocument1 pageBank Transfer Problemsachin2727No ratings yet

- Use of TemplateDocument13 pagesUse of Templatesachin2727No ratings yet

- Paper 3 - Audit - TP-2Document6 pagesPaper 3 - Audit - TP-2Suprava MishraNo ratings yet

- Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of "Global Stablecoin" ArrangementsDocument73 pagesRegulation, Supervision and Oversight of "Global Stablecoin" ArrangementsForkLogNo ratings yet

- Bir - Train Tot - Transfer TaxesDocument14 pagesBir - Train Tot - Transfer TaxesGlo GanzonNo ratings yet

- Audit Planning and Materiality: Concept Checks P. 209Document37 pagesAudit Planning and Materiality: Concept Checks P. 209hsingting yuNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document47 pagesModule 2Manuel ErmitaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-Introduction To Cost Accounting: Multiple ChoiceDocument535 pagesChapter 1-Introduction To Cost Accounting: Multiple ChoiceAleena AmirNo ratings yet

- PA 242.2 Problem Set 2Document2 pagesPA 242.2 Problem Set 2Laurence Niña X. OrtizNo ratings yet

- BRM ProjectDocument23 pagesBRM ProjectimaalNo ratings yet

- Twenty-To-One - Wealth Gaps Rise To Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks and HispanicsDocument39 pagesTwenty-To-One - Wealth Gaps Rise To Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks and HispanicsForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- DD Rules V 4 19 Rulebook Nov 2011 FinalDocument68 pagesDD Rules V 4 19 Rulebook Nov 2011 Finalimesimaging100% (1)

- Financial ManagementDocument96 pagesFinancial ManagementAngelaMariePeñarandaNo ratings yet

- Tradewell Company ProfileDocument11 pagesTradewell Company ProfilePochender vajrojNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument20 pagesCambridge International Examinations Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationAung Zaw HtweNo ratings yet

- Pertinent Laws in Urban DesignDocument31 pagesPertinent Laws in Urban DesignAnamarie C. CamasinNo ratings yet

- Commercial Arithmetic PDFDocument8 pagesCommercial Arithmetic PDFagnelwaghelaNo ratings yet

- Understanding LiabilitiesDocument2 pagesUnderstanding LiabilitiesXienaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Financial Performance Ratios for HP, IBM and DELL from 2008-2010Document35 pagesAnalysis of Financial Performance Ratios for HP, IBM and DELL from 2008-2010Husban Ahmed Chowdhury100% (2)

- Leibowitz - Franchise Value PDFDocument512 pagesLeibowitz - Franchise Value PDFDavidNo ratings yet

- Impact of Merger On Financial Performance of Nepalese Commercial BankDocument4 pagesImpact of Merger On Financial Performance of Nepalese Commercial BankShrestha Photo studioNo ratings yet

- Bank Marketing 1Document69 pagesBank Marketing 1nirosha_398272247No ratings yet

- Tax - AssignmentDocument29 pagesTax - Assignmentjai_thakker7659No ratings yet

- Business Fundamentals BSC Curriculum IntegrationDocument36 pagesBusiness Fundamentals BSC Curriculum IntegrationsuryatnoNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Toward The Government Shutdown and The Debt Ceiling, October 2013Document34 pagesAttitudes Toward The Government Shutdown and The Debt Ceiling, October 2013American Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Interest Rates and Security ValuationDocument40 pagesChapter Three: Interest Rates and Security ValuationOwncoebdiefNo ratings yet

- SesesesesemmmmmemememememeDocument1 pageSesesesesemmmmmemememememeNorr MannNo ratings yet

- Transaction Details PayPalDocument1 pageTransaction Details PayPalChristine Eunice RaymondeNo ratings yet

- (P3,300,000.00), Philippine Currency, Payable As FollowsDocument3 pages(P3,300,000.00), Philippine Currency, Payable As FollowsMPat EBarr0% (1)

- Allied Banking Corp vs Lim Sio WanDocument12 pagesAllied Banking Corp vs Lim Sio WanKathleen MartinNo ratings yet

- Contract of Indemnity and Guarantee NotesDocument4 pagesContract of Indemnity and Guarantee NotesHarshit jainNo ratings yet

- Dispute FormDocument1 pageDispute Formمحمد شزراﻷيمين بن عبدالقاسيمNo ratings yet