Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Avedon

Uploaded by

payerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Avedon

Uploaded by

payerCopyright:

Available Formats

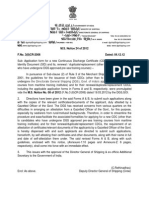

ART & COMMERCE

Defining beauty

through Avedon

By Philip Gefter,

nytimes.com, Sept. 18, 2005

RICHARD AVEDON honored women. For

nearly half a century, taking photographs for

the top two fashion magazines in the world,

Harperʼs Bazaar and Vogue, women were the

subject and the target of his insistent, yet sym-

pathetic gaze. From the models in his fashion

tableaux to his later, unembellished portraits

of artists, writers, intellectuals, socialites and

hardscrabble workers in the American West,

his regard for the fully realized individual re-

mained constant.

At first, Avedon practiced taking fashion

pictures of his beautiful younger sister, Lou-

ise, and throughout “Woman in the Mirror”

(Abrams), a new collection of Avedonʼs pic-

tures, that respectful posture turns all women

into the potential sister — an undeniably beau-

tiful, but deeply kindred spirit. There is an erot-

ic component to some of these pictures, but he

seems less concerned with menʼs arousal than

with the subtle cues women take from one an-

other, a view that places sexuality in a larger

constellation of human qualities.

After being discovered by Alexey Brodo-

vitch, the art director of Harperʼs Bazaar, Ave-

don began taking photographs for the maga-

zine in 1947, the year Dior introduced the New

Look and just two years before Simone de

Beauvoirʼs “Second Sex” was published. The

CMNS 375 1 Readings

New Look was modernity incarnate and the sculptural lines and

cosmopolitan flourishes were perfect for Avedon, who seized upon

it to make cinematic images in which the models inhabited the

clothes like characters in a movie. And, as if Simone de Beauvoir

were looking over his shoulder, Avedonʼs photography animated

women with spirit and determination.

Through Avedonʼs eyes, female beauty is not viewed with dis-

trust, as a collection of wiles and veils that can manipulate, obfus-

cate or seduce. In one photograph, the model Liz Pringle stands

effortlessly poised in a boat, with the manner of an heiress in a

breezy movie from the 1950ʼs. She holds a cigarette and looks our

way with the sly grin of a secret shared, as if we are among her

closest friends. You know the picture is all about the clothes, but

the soignée sophistication of the scene is what draws you in.

He had many muses, among them Dovima, whose name alone

conjures an exotic creature of myth. (In fact, Dorothy Virginia Mar-

garet Juba created her name from the first two letters of each of her

given names.) In one Avedon picture, she wears a dress by Jacques

Fath, and it appears as some-

thing sacred and ceremonial,

Avedon distilled a Dovima assuming the stature

variety of elements of a pageant queen.

into a simple and His photograph of Penelope

distinct visual Tree is as much a portrait of

signature: the element the real society girl as it is a

of surprise, for model wearing the latest fash-

example, in his most ion. The pants suit was a new

famous picture of concept at the time, the bell

Dovima with the bottom an emerging style;

elephants at the his picture is playful and

Cirque d’Hiver in free-spirited, and she strikes

Paris, the large, a Pippi Longstocking note -

bulbous creatures unconventional but all grown

forming a backdrop of up, cosmopolitan and top-of-

unharnessed animal the-moment, out in the world

instinct against which on her own terms.

the elegance of high And his portrait of the writ-

fashion stands in er Renata Adler is stripped of

dramatic relief. decoration, leaving the anato-

CMNS 375 2 Readings

downtrodden young woman from his After being discovered by

series “In the American West.” “To Alexey Brodovitch, the art

him, Debbie McClendonʼs fragility and director of Harper’s Bazaar,

tenderness resembled a Botticelli.” Avedon began taking

Movie history has permanently photographs for the

married Richard Avedon to Audrey magazine in 1947, the year

Hepburn thanks to “Funny Face,” star- Dior introduced the New

ring Fred Astaire as the fashion pho- Look. The New Look was

tographer Dick Avery, who is based on modernity incarnate and the

Avedon. In the book, “Richard Ave- sculptural lines and

don: Made in France,” Judith Thurman cosmopolitan flourishes were

writes that “Funny Face” is an artifact perfect for Avedon, who

of a remote, lost civilization. Three of seized upon it to make

its purest pleasures have not dated: cinematic images in which the

Hepburnʼs face, Givenchyʼs couture, models inhabited the clothes

and Astaireʼs dancing — all pertinent, like characters in a movie.

the dancing, in particular, to Avedonʼs

work.

She equates Astaireʼs buoyancy to Avedonʼs pictures, the classical discipline with

which the dancer, like the photographer, made the artificial and rehearsed seem ef-

fervescent and spontaneous.

Avedon distilled a variety of elements into a simple and distinct visual signature:

the element of surprise, for example, in his most famous picture of Dovima with

the elephants at the Cirque dʼHiver in Paris, the large, bulbous creatures forming a

backdrop of unharnessed animal instinct against which the elegance of high fashion

stands in dramatic relief. Or glamour in his picture of Sunny Harnett, the top model

in her day, at a posh European casino; he made her shimmer like a Hitchcock blonde

in a Madame Grès dress. Or wit in his picture of Carmen stepping off the ground, as

if by wearing a Pierre Cardin coat you, too, could be walking on air.

He played a stunning hand with visual onomatopoeia as well: his portrait of Kath-

arine Hepburn with her mouth opened elicits the very sound of her distinctive accent;

his portrait of Louise Nevelson, with her heavy eyeliner and sculptural jewelry, turns

her into one of her own works of art; and his portrait of Marella Agnelli, in which her

my of her face, the intransigence of her posture and the gravity of her braid to rep- elongated neck conjures Modigliani, her entire form as graceful as a Brancusi.

resent a modern-day Athena, goddess of the intellect, taking our measure as much Despite decades of imitators, Avedon has proved inimitable. His curiosity fueled

as we take hers. his imagination. He anticipated the tone of each era with a sophistication that was

“Dick had a very particular taste for what he thought was a beautiful woman,” precision-cut in the stratosphere of art, fashion and culture at which he so naturally,

said Norma Stevens, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation. Paging and tenaciously, hovered. He never stopped experimenting with the photographic

through the book in her New York office, she stopped at a portrait of a seemingly image and, always, his pictures reflect a regard for women that was truly debonair.

CMNS 375 3 Readings

An interview with Richard Avedon

By Nicole Wisniak. Egoïste, Sept. 1984

Nicole Wisniak: Do you think a photographer is a person obsessed by the fact that

things disappear?

Richard Avedon: I canʼt generalize. All that remains of my father is my photo-

graph, that is to say film, but I donʼt think thatʼs why I photograph. I see all the time

— I very often donʼt listen. I can be in conversation with someone and at a certain

point, stop hearing what is said, start pretending to listen. My good friends know

when that happens.

The way I see is comparable to the way musicians hear, something extra sensory.

Not judgmental. I donʼt differentiate between an idea of what is beautiful and what is

not. What I see is a reaffirmation of the many things I need to feel. It has to do with

obsessive qualities, not explainable. I am a natural photographer. It is my language, I

speak through my photographs more intricately, more deeply than with words.

N.W.: But this overdeveloped eye is sometimes pitiless. You reveal in your por-

traits facets of character that people would perhaps have preferred not to show. Do

you think it is possible to hide oneʼs self in front of your camera?

R.A.: I am not necessarily interested

in the secret of a person. The fact that

‘There is no truth in there are qualities a subject doesnʼt

photography. There is no want me to observe is an interesting

truth about anyone’s person. fact. Interesting enough for a portrait.

My portraits are much more It then becomes a portrait of someone

about me than they are about who doesnʼt want something to show.

the people I photograph. I That is interesting. There is no truth in

used to think that it was a photography. There is no truth about

collaboration, that it was anyoneʼs person. My portraits are much

something that happened as more about me than they are about the

a result of what the subject people I photograph. I used to think

wanted to project and what that it was a collaboration, that it was

the photographer wanted something that happened as a result

to photograph. I no longer of what the subject wanted to project is complicated. Everyone comes to the camera with a certain expectation and the

think it is that at all. The and what the photographer wanted to deception on my part is that I might appear to be indeed part of their expectation. If

photographer has complete photograph. I no longer think it is that you are painted or written about, you can say: but thatʼs not me, thatʼs Bacon, thatʼs

control, the issue is a moral at all. The photographer has complete Soutine; thatʼs not me, thatʼs Celine.

one and it is complicated.’ control, the issue is a moral one and it N.W.: Picasso answered to that saying about Gertrude Stein: “Thatʼs not how she

CMNS 375 4 Readings

“May I do a portrait of you?” ‘I used to believe that I

It is complicated and unresolved in could only photograph what

my mind because I believe in moral I knew and understood. I

responsibility of all kinds. I feel I understood artists, people

have no right to say, “This is the way of high achievement, power,

it is” and in another way, I canʼt help beauty, at least I thought I

myself. It is for me the only way to understood those things.

breathe and to live. I could say it is the I said once in an interview

nature of art to make such assumptions that I had no idea what it

but there has never been an art like was like to be black or what

photography before. You cannot make it was like to be a factory

a photograph of a person without that worker, and so I couldn’t

personʼs presence, and that very pres- photograph them. Of course,

ence implies truth. A portrait is not a it was not true. ... As a

likeness. The moment an emotion or matter of fact, the people I

fact is transformed into a photograph have photographed for this

it is no longer a fact but an opinion. book seemed more generous

There is no such thing as inaccuracy in with their selves, less

a photograph. All photographs are ac- guarded, often easier to see.’

curate. None of them are truth.

N.W.: You have been working for

many years on a new book on the working class. Did you begin this new work be-

cause you were fed up with the elite?

R.A.: No, not at all. I have been working for many many years as a portrait pho-

tographer, on portraits of Americans. But I used to believe that I could only photo-

graph what I knew and understood. I understood artists, people of high achievement,

power, beauty, at least I thought I understood those things. I said once in an interview

that I had no idea what it was like to be black or what it was like to be a factory

worker, and so I couldnʼt photograph them. Of course, it was not true. But it took

me a long time to know in my stomach that people share the same concerns, and that

confronting an oil worker is very little different than say, a writer. Itʼs just a ques-

tion of language. As a matter of fact, the people I have photographed for this book

seemed more generous with their selves, less guarded, often easier to see.

N.W.: But not anybody is a good subject for you. How do you choose your sub-

was when I painted her but thatʼs how she will be sooner or later.” jects?

R.A.: Thatʼs pretty grand of him. On the other hand, now that she is dead, visually R.A.: Very few people are suitable subjects for me. In the same way that not every-

that is all she is. It is a terrible responsibility for a photographer. The subject was one looks like a Modigliani or would have been a correct model for Julia Cameron.

there — the subject can never say — that is not me. It is even worse in the case of Itʼs a difficult question because I donʼt formalize these things. I am interested in con-

photojournalism, when the photograph is taken without permission. At least I ask, nections between people of remote experience, in similarities that are unexpected,

CMNS 375 5 Readings

unexplained. When you see this new book, you will see a man, a worker in

Colorado, who has qualities exactly like James Galanos. Galanos is a dress

designer in Beverly Hills who dressed the wife of President Reagan. The

man in Colorado is a factory worker who wraps packages. That facinates

me. If you look at the portraits of the “Chicago 7,” you will find similarities

to The Mission Council. Paradox, irony, contradiction — these interest me

in a photograph. Contradications within one person: the contrast possibly

between the gentleness and the delicacy of the hands of a subject and the

suspicion and the lack of trust on his face.

N.W.: There is also a contradiction in your work. Your fashion pictures

and then your portraits, which seem to show a more tragic side of life.

R.A.: I donʼt think one is at all a reaction to the other, which is a view

sometimes held about Penn, Arbus and myself: that the serious, or if you

want, the “tragic” quality of our portraits is a reaction to the artificial de-

mands of fashion. I think there is a tendency to categorize photographers

with assumptions that would never be made of writers. If an author writes

a comedy or a tragedy and then an essay or is politically concerned, no on

questions. No one asks why a philosopher writes a novel or a poem, or why

Picasso did ballet costumes. That generosity is not extended to fashion pho-

tographers. Iʼve had to deal with that always — less now — but still.

Fashion photography is not an art that can grow indefinitely. It is con-

stantly taking and dealing with the surface of things and that doesnʼt attract

me anymore. When I was young, my needs as an artist were exactly the

needs of the magazine I worked for — Harperʼs Bazaar. They published

what I wanted to express. (That went on for 20 years — Embarrassing!) At

a certain point, the necessities of fashion magazines were no longer mine,

no longer interesting.

As a commercial photographer, fashion is a necessary part of my com-

mercial existence. I find it easy. It underwrites and supports my life and

other work that I prefer to do.

N.W.: To be a photographer — was it that most obvious way to earn

money in the early fifties?

R.A.: My father wanted me to be a businessman because he had suffered

terribly as a Russian Jew in New York City at the turn of the century. He had

a terrible life as a child, one of six children deserted by his father, sent to an

orphan asylum, he had a tragic quality and an exaggerated sense of danger.

He wanted me to be prepared for what he calls The Battle in the ways that

he felt one had to be prepared: through education, physical strength and

money.

CMNS 375 6 Readings

I am a complete composite of my mother and father. She began to

be a sculptress at 75, working with granite and marble. My mother

loved the arts, was politically active, and always encouraged me

to be an artist. She was and is completely supportive. During the

depression she stole lilacs. She says about artists, “He is the real

thing” or “Heʼs not the real thing” and thatʼs that.

Anyway, photography was the only thing I could do. I have been

a photographer since at least the age of 13. My family was in the

business of fashion and my parents subscribed to Harperʼs Bazaar,

Vogue, and Vanity Fair when I was a child. I saw fashion photog-

raphy and theater portraits by Steichen, Munkacsi and Man Ray in

each issue and I began to imitate them by photographing my little

sister. She was very, very beautiful, two years younger than I. Her

beauty was the event of our family and the destruction of her life.

She was treated as if there was no one inside her perfect skin, as if

she was simply her long throat, her deep brown eyes. I think she

believed she existed only as skin, and hair, and a beautiful body.

Interestingly enough, I had not looked at a photograph of her in

30 years, and only last week opened a package of my earliest pic-

tures, taken when I was an adolescent. Every family thinks their

daughter and son are the most beautiful children in the world, but

my sister Louise, (I photographed her from 14 to 18), was truly

a world class beauty, and I never knew it until last week. What I

discovered was that she was the prototype of what I considered to

be beautiful in my early years as a fashion photographer. All my

first models: Dorian Leigh, Elise Daniels, Carmen, Marella Agnelli,

Audrey Hepburn, were brunettes and had fine noses, long throats,

oval faces. They were all memories of my sister. My sense of what

was beautiful was established very early through the way in which

I experienced her.

N.W.: Where is she now?

R.A.: She is dead. She died in a mental institution at the age of

40. She withdrew completely in her late adolesence.

N.W.: You mean she was killed by her beauty?

R.A.: Depersonalized, maybe. Destroyed, possibly; I think really

by the power of her beauty. It is as isolating as genius, or deformity.

Unlike genius, it is one of the qualities that removes you from the

world, but offers no real compensation. I have always been aware

of a relationship betweeen madness and beauty. Does this help to

CMNS 375 7 Readings

‘I never felt that anything I explain some of what appear to be

ever did was good enough contradictions in my work? Itʼs only

and frankly, a large part of me one part. It had nothing to do with the

still thinks exactly that way discipline of work, and other things,

about everything I do — it is but you will find if you look to the por-

not good enough — nothing is traits, that connection. A possibility of

ever even near good enough. failure and danger and poetry in life

But that’s not a regret. I just — and the close line.

feel that I know more than I N.W.: Since 40 years, you have pho-

can put into my work.’ tographed painters, politicians, artists,

workers, famous and unfamous people.

What feeds your curiosity for people?

R.A.: I donʼt think analytic explanations suffice but there is a little bit of truth in

everything, in Freud, in Pavlov, in genetics, in enviroment. I grew up with a first

cousin, two years older than I. I was deeply in love with her from the age of 4 until I

was 18. It was only with her that I could breathe freely. We were precocious from the

start. When the Cocteau movie “Les Enfants Terribles” came out, we knew we were

those children. We saw it over and over. Our feelings for each other were so intense,

so forbidden so conspiritorial. I knew for myself — I canʼt speak for her — that if I

was ever to complete myself, grow up and out into the world, we had to shatter our

perfect hothouse. In all the years that a young man first experiences life apart from

the family, I knew only one person. I think my entire character was formed through

that powerful relationship. And my life has gone on, one person at a time.

N.W.: This relationship with one person at a time is replayed in your studio, when

you do a portrait?

R.A.: Oh yes! Intensely — but in photography it is an unearned intensity. For

example, I have never become a friend — or very rarely — of anyone I have pho-

tographed. I would never, for many many years, enter a room after photographing a

celebrated person and assume that if he were there, he would acknowledge me. The

kind of embarassing intensity of these peculiar intimacies and needs, the needs of

the subject to give something to the camera and to me, and my need to take that in

order to express myself — is complicated and unearned. I have never felt that I had

the right to presume that there was anything but the picture between us. Itʼs less than

an hour, and itʼs over — completely.

N.W.: Havenʼt you ever been seduced by some of these people?

R.A.: As my book Portraits was being completed, there were certain artists whose

work had affected me, whom I had not photographed, and one of them was Jean

Renoir. Renoir lived in Beverly Hills and I went to him. His home looked like ev-

erything Iʼd always thought a home should be. It looked like south of France. It

CMNS 375 8 Readings

didnʼt look like Beverly Hills. There were flowers in and out of the rooms and

sunshine coming through the windows. And a long table in the middle of the

room. A long table at the center of a house has always had great meaning for

me. When I arrived, I was shown to his bedroom. He was naked, being helped

to dress, completely unembarassed by my presence. He was old and quite sick

at the time and he walked with difficulty, with a walker. There was something

so moving about his face and about his life and his work and what he stood for.

He was one of the last people I felt in awe of. When the sitting was over, (in

those days I worked with incredible intensity, I mean my heart would pound

out of control while I photographed), Renoir said, “Wonʼt you join us?”

So I sat at the table and some friends arrived with vodka and a Sunday cake

and Renoir sat down. Behind him was a portrait of him as a child painted by

his father and the potteries he had made as a child guided by his father.

A young Czechoslovakian director who was there visiting started to talk

with Renoir about Film. What happened to me used to happen to me very often

— I froze, I couldnʼt speak or think. I felt inadequate. I thought — what can I

say or contribute to anything that happens at this table. Well, actually nothing

so grand was happening. I considered myself very good at disguising my feel-

ings and I knew there was no necessity for me to speak. I could legitimately

be a quiet person. But I was paralyzed inside. Smiling, trying to appear com-

fortable, thinking — what right do I have to be at this table? I came to do my

photograph, I should leave. I am not a friend of the Renoirs, this is Sunday.

Renoir stood to go to the bathroom and I used that occasion to say goodbye

to everyone. As I walked to the front door, he came our of his bedroom with his

walker which sort of blocked my way. And we were stuck there, in the narrow

hall, in this confrontation. I extended my hand and said, “Monsiour Renoir,

thank you very much for allowing me to photograph you.” And he looked into

my eyes and spoke, and Iʼll never forget his words, “It is not what is said that

matters, itʼs the feelings that cross the table.”

I froze my face. I walked to the car and wept. Imagine a man in his eighties,

sick as he was, knowing what was happening to me at the table, and to care,

and to say it. Well, thatʼs my kind of standard for human behavior. To be able

to be that present in each moment. The quality of paying attention that he had,

and then the compassion. I think there is not much more to life than that story:

to be that age, surrounded by your fatherʼs works of art, to have created your

own, to live in a house with sunshine falling through the windows, and a wife,

and a jar of vodka with spirals of lemon rind in it, and friends and your own

son who has become a teacher and his children sitting with the grownups, on

Sunday — and to still pay that kind of attention to a stranger.

CMNS 375 9 Readings

N.W.: Do you have any regrets?

R.A.: I never felt that anything I ever did was good enough and frankly,

a large part of me still thinks exactly that way about everything I do — it is

not good enough — nothing is ever even near good enough. But thatʼs not

a regret. I just feel that I know more than I can put into my work.

N.W.: Does it make you suffer?

R.A.: No. Not that. It makes me work.

N.W.: What makes you anxious?

R.A.: The unexplainable shifts of my feelings. From moment to moment

I can shift from someone who thinks he can deal with everything to some-

one who canʼt think. It has nothing to do with reality. I like to believe itʼs

chemical. I used to think there was a Freudian answer. (He laughs). What I

do know about myself is that I am best in intense short encounters. I mean

the way in which making pictures is very intense and short, compared to

writing.

Everything I do, it seems to me, has passion about it and then suddenly

the drop and then withdrawal, which is not necessarily depression. It can be

planes or sleep or doing puzzles, but I have to pull back. I am not capable

of living on my most intense level for a long period of time. I think I might

crack. Thatʼs probably why I still do a bit of fashion photography — to

relieve the tension.

N.W.: Did you ever feel it would have been possible for you to become

insane?

R.A.: Maybe, when I was young, yes. At certain periods when there

were real life pressures, rites that seemed impossible to meet, I thought: I

am not going to make it. But I always had the ability to escape into reality,

into work. Many things have called to me in my life, many things in all ar-

eas of my life, and they have found their proper home in my photographs.

N.W.: But not on your

face. You look very serene.

‘Paradox, irony, R.A.: Itʼs because, per-

contradiction — these haps, the storm approaches

interest me in a photograph. my pictures instead of my

Contradications within one face. Thatʼs a funny thought.

person: the contrast possibly (He laughs.)

between the gentleness and

the delicacy of the hands of a

subject and the suspicion and

the lack of trust on his face.’

CMNS 375 10 Readings

You might also like

- Glen Clark QADocument2 pagesGlen Clark QApayerNo ratings yet

- Circ 2006 MHDocument5 pagesCirc 2006 MHpayerNo ratings yet

- 375 OutlineDocument6 pages375 OutlinepayerNo ratings yet

- 082 Dates 2Document2 pages082 Dates 2payerNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Media Plan - Vinod Tawde JiDocument16 pagesMedia Plan - Vinod Tawde JiMaximus MarihuiNo ratings yet

- Community Vigil To Remember Calvin Riley: Deadline ComingDocument28 pagesCommunity Vigil To Remember Calvin Riley: Deadline ComingSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- A Robot Wrote This Entire Article. Are You Scared Yet, Human - Artificial Intelligence (AI) - The GuardianDocument10 pagesA Robot Wrote This Entire Article. Are You Scared Yet, Human - Artificial Intelligence (AI) - The GuardianMac Norhen E. BornalesNo ratings yet

- M500 NotesDocument4 pagesM500 NotesNick Mendoza0% (2)

- 1.1. Inglês - Exercícios Propostos - Volume 1Document36 pages1.1. Inglês - Exercícios Propostos - Volume 1danieltb2000No ratings yet

- Great Drawings and Illustrations From Punch 1841-1901Document166 pagesGreat Drawings and Illustrations From Punch 1841-1901torosross6062100% (3)

- Renewel of CDCDocument20 pagesRenewel of CDCShivam ShiviNo ratings yet

- Myawady Daily Newspaper 19-10-2018Document31 pagesMyawady Daily Newspaper 19-10-2018TheMyawadyDaily100% (1)

- Alagadan or GrammarDocument12 pagesAlagadan or Grammarapi-296021938No ratings yet

- LSDE January 10, 2013Document12 pagesLSDE January 10, 2013LeyteSamar DailyExpressNo ratings yet

- The Speckled Band WorksheetDocument2 pagesThe Speckled Band WorksheetKoray GerguzNo ratings yet

- Customizing BricsCAD V18 PDFDocument590 pagesCustomizing BricsCAD V18 PDFLeonardo Reyes NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Armalite AR-7 RifleDocument6 pagesArmalite AR-7 Rifleblowmeasshole1911No ratings yet

- F Scott Fitzgerald Babylon Revisited PDFDocument2 pagesF Scott Fitzgerald Babylon Revisited PDFAndrewNo ratings yet

- Gillette Mach 3 - Brand ElementsDocument23 pagesGillette Mach 3 - Brand Elementsmanish_mittalNo ratings yet

- Guidelines MLADocument31 pagesGuidelines MLAKostas SasNo ratings yet

- Persiapan USP1 2021Document12 pagesPersiapan USP1 2021koji nyopiNo ratings yet

- The 6th ISSSHE TemplateDocument5 pagesThe 6th ISSSHE TemplateAmaliatul HubbillahNo ratings yet

- Lightweight 5.56mm Squad Automatic WeaponDocument2 pagesLightweight 5.56mm Squad Automatic WeaponBibo MovaNo ratings yet

- NP Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer (1952)Document12 pagesNP Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer (1952)Sanchit SubscriptionsNo ratings yet

- S03-16 The Midnight MaulerDocument26 pagesS03-16 The Midnight MaulerFrank J. Bird100% (2)

- Images of Nurses in MediaDocument8 pagesImages of Nurses in MediaRufus Raj50% (2)

- Threshold 33Document208 pagesThreshold 33dok6506No ratings yet

- SPM Bi BS 4 1Document24 pagesSPM Bi BS 4 1Kay AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1 - Business LawDocument3 pagesQuiz 1 - Business LawmitemktNo ratings yet

- Typography - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument14 pagesTypography - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaZa-c Pelangi SenjaNo ratings yet

- Good Manners With FamilyDocument28 pagesGood Manners With FamilyBiglolo Biglala100% (2)

- Millbrae Officials Eye Community Center Tax: Trump Travel BanDocument40 pagesMillbrae Officials Eye Community Center Tax: Trump Travel BanSan Mateo Daily Journal100% (1)

- MOCK TEST 1 - Entrance Exam To Colledge 2022Document5 pagesMOCK TEST 1 - Entrance Exam To Colledge 2022lqnam74No ratings yet