Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Revolution Will Not Be Marginalized: Max Blumenthal Reports From Egypt's Counter-Counter-Revolution

Uploaded by

Pando DailyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Revolution Will Not Be Marginalized: Max Blumenthal Reports From Egypt's Counter-Counter-Revolution

Uploaded by

Pando DailyCopyright:

Available Formats

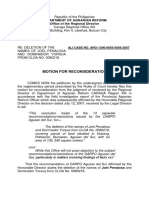

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No.

C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

RELEASE IN PART B6

From:

Sent:

To:

Subject:

Sidney Blumenthal <

Wednesday, December 12, 2012 8:53 PM

Re: H: Latest from the streets of Cairo. Lots of detail. Sid

Not in my family.

Seriously, long discussion, has to do with evolution and understanding of political leadership, but we

all know that. Spielberg and Tony Kushner, amazingly, for the first time in a major American film,

actually got it.

Original Message

From: H <HDR22 clintonemail.com>

To: 'sbwhoeop

'<

Sent: Wed, Dec 12, 2012 8:15 pm

Subject: Re: H: Latest from the streets of Cairo. Lots of detail. Sid

Why are liberals the world over so politically hopeless?

From: Sidney Blumenthal [mailto

Sent: Wednesday, December 12, 2012 05:22 PM Eastern Standard Time

To: H

Subject: H: Latest from the streets of Cairo. Lots of detail. Sid

http://www.nsfwcorp.com/dispatch/rejection-is-rejection

From: Max Blumenthal

TO: The Egypt Desk

Date: Dec 12th, 2012

The Revolution Will Not Be Marginalized:

Max Blumenthal Reports From Egypt's

Counter-Counter-Revolution

CAIRO, EGYPT: Inside a colonial era mansion that served as the headquarters of the liberal Wafd

Party, I angled for position among the cluster of reporters seated awkwardly, like kindergarteners, on

the dust-sodden, carpeted floor.

From the back of the room, cameramen bellowed "Sir! Sir! Ma'am! Sit down! Down!" jostling for

position as Mohammed El-Baradei shuffled briefly across the stage. As the crowd of reporters surged

forward, Baradei hurried behind two giant wooden doors and into a back room.

Baradei was the most prominent of the politicians gathered under the umbrella of the National

Salvation Front (NSF), a coalition of Egyptian parties united against President Mohamed Morsi and

the Muslim Brotherhood's divisive draft constitution.

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

Joining Baradei in the coalition was Dignity Party leader Hamdeen Sabahy, a former presidential

candidate, longtime dissident and left-wing Nasserist. Amr Moussa, a liberal former Mubarak regime

official and ex-Arab League chairman was welcomed into opposition ranks despite bearing the

oppressive aroma of the ancien regime. And then there was Ayman Nour, the centrist politician jailed

by Mubarak in 2005, filling out the roster of political heavyweights assembled under the banner of the

NSF.

While a crowd of young party officials and cameramen piled microphones on the podium at the front

of the room, I chatted with a few of the reporters seated beside me on the floor. None of them

expected the opposition to keep up its boycott of the referendum scheduled for December 15, when

Egyptians would go to the polls to vote on Morsi's proposed constitution. The conventional wisdom

held that they were set to lose by a wide margin against a Muslim Brotherhood machine that boasted

unmatched political discipline and a massive base in the rural provinces. Backed into a corner, the

opposition seemed to have only one viable option: an aggressive campaign to convince the public to

vote "no."

After an hour of waiting, NSF spokesman Hussein Abdel-Ghani appeared at the dais with a short,

stentorian announcement: "Rejection is rejection," he proclaimed. The opposition would boycott the

referendum until its three most ambitious demands were fulfilled: First, they wanted the referendum

vote to be postponed; second, they insisted on the revocation of Morsi's decree granting himself

unlimited power over the judiciary; and finally, they called for the draft constitution to be completely

scrapped. It was December 9, only six days before the scheduled vote.

Not only would the NSF turn its back on the referendum, its members vowed to obstruct the vote

through sit-ins and other unnamed methods of civil disobedience. "We are going to escalate our

actions," Abdel-Ghani said, warning that the referendum was "a recipe for violence." The Brotherhood

had used "terrorism" against supposedly peaceful demonstrators, he claimed, referring to the Roxy

Square clashes last Wednesday that left 8 dead and hundreds injured, and which witnessed heavy

violence from both sides. Now the opposition pledged to bring the heat, sending waves of

demonstrators into the streets until Morsi and the Brotherhood buckled.

"This is a revolution and we will use the same methods as we did against Mubarak," Abdel-Ghani

declared from the podium.

Despite its purported embrace of the revolutionary spirit emanating from the streets, the opposition

distanced itself from the message uniting the protesters who convened outside the Itehadeya

Presidential Palace each night -- "Leave!" -- blaming the calls for Morsi's ouster on the frustrations of

disenfranchised Egyptian youth. The NSF's inability to fully embrace the fervor of the demonstrations

suggested that it was the street leading opposition politicians, and not the other way around.

While the NSF sought to present a united front, rifts were beginning to appear. Ayman Nour had met

privately with Morsi and the Brotherhood's Wizard of Oz-like supreme leader, Khairat El-Shater,

agreeing to engage in the constitutional dialogue the rest of the opposition staunchly rejected. Nour's

freebooting embarrassed other NSF leaders, prompting his branding as a rogue and a sellout, while

Bahaa Anwar Mohamed, a member of Nour's Of Ghad party's high committee, told me the party was

considering moves to eject Nour from its ranks.

Two hours after the press conference, I was among the demonstrators assembled outside the

presidential palace. In the four nights after the deadly Roxy Square street battle, the protests had

taken on a festive, family friendly atmosphere, with demonstrations filled with an entirely new class of

participants, including members of the old establishment who looked upon the original Tahrir Square

revolution with suspicion and scorn. From the Gezira Club, a private riverside sports club, marches

filled with well-coiffed Cairene elites have poured into the Itehadeya rallies, with some first-time

demonstrators asking veteran activists for instructions on how to protest. Other loyalist strongholds

like the neighborhood of Abbaseya have contributed heavily to the anti-Morsi forces.

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

Throughout the January 25 revolution that toppled Mubarak in 2011, the conspiratorial satellite TV

demagogue Tawfiq Okasha assailed the demonstrators in Tahrir Square as foreign puppets bribed by

US and European interests. The message resonated among both lower class nationalists and members

of the genteel upper middle class. Now that members of the old establishment were protesting

alongside the original revolutionaries, Egyptian political identity was in flux.

"I used to recognize everybody at these demos," Gigi Ibrahim, the 26-year-old Tahrir veteran and

blogger, told me. "Now it's filled with new faces. A whole new sector has come out into the streets."

Ibrahim was excited about the possibilities presented by the new breed of protesters. "These people

used to say we were a bunch of foreign agents, and now they see that we are just people like them, and

they can respect what he have really been doing since the beginning."

Since the presidential palace became the ground zero of anti-government protests, the vendors and

graffiti artists familiar to Tahrir Square began a steady migration to the grass-lined boulevard outside

its walls. The palace's outer facade was covered in graffiti, and large banners hung before its facade

displaying slogans like, "Morsi hold back your thugs." "Game Over," another banner declared,

invoking the famous photo of a Tunisian protester displaying the slogan on a cardboard sign the day

before the fall of dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

The soldiers posted outside the palace had become part of the carnival scene, posing for photos with

beaming young men, even playing checkers with demonstrators on the chassis of their tanks. Once a

symbol of iron-fisted repression, the army was suddenly received by opposition elements as the

guarantor of civil society's security against Brotherhood aggression.

Inside a makeshift "museum of the revolution" installed on the grass across from the palace, next to

the line of protest tents, I met Hossam Fares (below), a dapper businessman in his early zpo's working

as the political marketing director for Baradei's Dosta Party. Fares was working the youthful crowds

milling about the tent, passing out fliers that outlined the constitution's most contentious articles and

urging everyone to vote against it. The following day, Dosta planned to blanket private Egyptian

television networks with commercials promoting a "no" vote.

"We're campaigning unofficially because we know first of all that we want the boycott," Fares told me.

"However, some people will not listen to us, and to those people we're going to explain them why they

should understand the constitution is a lousy product."

With its supposedly "unofficial" push for voting against the constitution, elements in the opposition

were already participating in the referendum they rejected and claimed to be boycotting. Finally, on

December 12, the NSF ended the rejectionist charade, throwing its political apparatus into full

campaign mode just three days before the referendum was to take place. But with 90 percent of

Egyptian Judges Club members refusing to supervise the voting, leaving only 7000 judges to preside

over some 14,000 polling places, it was unclear how the vote could happen anyway.

The past week has been marked by attacks carried out on Muslim Brotherhood party headquarters

across Cairo by the nationalist football hooligans known as the Ultras. As the street muscle of the

opposition, the Ultras seemed intent on fomenting enough destabilization to topple the presidency. In

the early morning two nights ago, I watched young men armed with pistols and clubs pour out of

Tahrir Square, clashing with apparent Muslim Brotherhood attackers half a block from my hotel. By

stepping back from the boycott and calls for "escalation," the NSF may have tamped down on the

chaos in the streets, preventing a possible intervention by the army.

Until the zero hour of the referendum, confusion reigned. And the opposition was making up its

strategy as it went along. "We are businessmen without many years of political experience," Hesham

Elaiwy, a Dostor councilor representing the Heliopolis and Nasser City areas of Cairo, told me. "Some

of us read about politics but we have never done it before now."

As the last protesters trickled out of the presidential palace demonstration, a group of young people

gathered around a DJ playing revolutionary tunes and rallied their spirits for the struggle ahead. I

followed Fares out of the protest area with two journalistic colleagues, walking past a makeshift

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

checkpoint and around a giant concrete wall installed by the army to obstruct street clashes. A few

minutes later, we Were ensconsed in the leather interior of Fares' BMW 5 Series, cruising into central

Cairo to the sound of Joe Cocker grunting out soft rock ballads.

"This is gonna take quite some time," Fares remarked. "You have an organization of people in the

Brotherhood who want to enforce their ideas on the whole population. They believe they are doing

something for the^ good of their religion, and the good of their beliefs, so they won't give it up. And we

won't accept it. So it will be a long struggle."

Fares dropped us off on 26 July street, the central artery of Cairo's affluent Zamalek district, a mecca

for Western expatriates and cosmopolitan Cairene youth. Within the radius of a few blocks of

crumbling, soot-stained pavement were dozens of trendy bars, cafes, and boutique shops. We

searched out a place for a drink after the long day, but could only find one that was still serving. It was

L'Aubergine, an upscale French bar and restaurant officially boycotted by local social justice activists

for its refusal to allow veiled women through its doors.

Near the back of the bar, we spotted a friend who worked for a separatist Basque newspaper drinking

with a prominent hammer-and-sickle tech guru who had earned international renown during the

heady days of the Tahrir Square revolution. I seated myself nearby, ordered a plate of ciabmeat ravioli

and sipped on a Johnny Walker Black, doing my best to tune out the heated argument Marxist theory

that had suddenly erupted at their table. "Workers aren't going to lead the revolutionary struggle," the

Egyptian activist insisted. "The inspiration is going to have to come from the intellectuals, the creative

class."

On opposite walls of the low-lit bar, flatscreen TV's displayed footage of male models strutting down

the catwalk of a European fashion show in tight, pleated slacks and weird insect glasses. Beneath a

soundtrack of generic techno thumping from the speakers installed in the ceiling, the revolutionary's

American accented voice bellowed across the bar -- "and that's why I'm a Leninist!"

Rotographs: Max Blumenthal

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05793493 Date: 11/30/2015

You might also like

- Opponents of Egypt's Leader Call For Boycott of Charter VoteDocument6 pagesOpponents of Egypt's Leader Call For Boycott of Charter VoteLong Dong MidoNo ratings yet

- 07-02-11 - Protests Demanding Mubarak's Resignation Grow Stronger Despite Some Government ConcessionsDocument8 pages07-02-11 - Protests Demanding Mubarak's Resignation Grow Stronger Despite Some Government ConcessionsWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- The Second, People-Led RevolutionDocument45 pagesThe Second, People-Led RevolutionDr. Iman BibarsNo ratings yet

- Egypt's Protests: What's Next?Document5 pagesEgypt's Protests: What's Next?Amy Tryabto ArifinNo ratings yet

- Some Syrians Vote, As Others Are AttackedDocument5 pagesSome Syrians Vote, As Others Are AttackedcocoopuiNo ratings yet

- Heavy Gunfire Rings Out in Cairo Protest SquareDocument5 pagesHeavy Gunfire Rings Out in Cairo Protest SquareTmr Gitu LoohNo ratings yet

- 02.07.13 Morsi Faces Ultimatum As Allies Speak of Military Coup'Document5 pages02.07.13 Morsi Faces Ultimatum As Allies Speak of Military Coup'anirudhadapaNo ratings yet

- 19-07-13 The Grand Scam: Spinning Egypt's Military CoupDocument10 pages19-07-13 The Grand Scam: Spinning Egypt's Military CoupWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Traub, James. 2007. "Islamic Democrats - " New York Times Magazine - 44-49Document21 pagesTraub, James. 2007. "Islamic Democrats - " New York Times Magazine - 44-49Rommel Roy RomanillosNo ratings yet

- Military Resistance 9B Issue: 4 "We Can't Go Back Now"Document31 pagesMilitary Resistance 9B Issue: 4 "We Can't Go Back Now"paola pisiNo ratings yet

- Turc Des Affairs EtrangersDocument3 pagesTurc Des Affairs EtrangersOğuzhan ÖztürkNo ratings yet

- The Irresistible Rise of The Muslim Brothers Fawas Gerges Published 28 November 2011Document14 pagesThe Irresistible Rise of The Muslim Brothers Fawas Gerges Published 28 November 2011Aşır Yüksel KayaNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Vote Time ArticleDocument3 pagesEgyptian Vote Time ArticleHayleyNo ratings yet

- Robert Fulford: A New Politics Emerges in Middle East. It Doesn't Involve DemocracyDocument4 pagesRobert Fulford: A New Politics Emerges in Middle East. It Doesn't Involve DemocracyAnonymous A6YLiJBtNo ratings yet

- mg342 AllDocument24 pagesmg342 AllsyedsrahmanNo ratings yet

- A Tunisian-Egyptian Link That Shook Arab History: FacebookDocument7 pagesA Tunisian-Egyptian Link That Shook Arab History: FacebookWaleed FekryNo ratings yet

- Egypt Crowds Unmoved by Mubarak's Vow Not To Run: Tahrir SquareDocument4 pagesEgypt Crowds Unmoved by Mubarak's Vow Not To Run: Tahrir SquareGerardoNo ratings yet

- SNHR: Violations of The Right of Artists in SyriaDocument50 pagesSNHR: Violations of The Right of Artists in SyriaimpunitywatchNo ratings yet

- Arab Spring-1Document30 pagesArab Spring-1Ishika JainNo ratings yet

- Mansour in Reconciliation EffortsDocument2 pagesMansour in Reconciliation EffortsGhulam Hassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Bahrain Sunnis Defend MonarchyDocument2 pagesBahrain Sunnis Defend MonarchyMissKuoNo ratings yet

- Global CrisisDocument12 pagesGlobal CrisisDavid GadallaNo ratings yet

- Bahrain Media Roundup: Read MoreDocument3 pagesBahrain Media Roundup: Read MoreBahrainJDMNo ratings yet

- Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyFrom EverandEvidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyNo ratings yet

- Tunisia Fighting Instability After Second Politician AssassinationDocument2 pagesTunisia Fighting Instability After Second Politician AssassinationYousuf AliNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 19, 6-8 Amwell Street, London EC1R 1UQ Tel: (+44) 20 7278 9292 / Fax: (+44) 20 7278 7660 WebDocument2 pagesARTICLE 19, 6-8 Amwell Street, London EC1R 1UQ Tel: (+44) 20 7278 9292 / Fax: (+44) 20 7278 7660 Webapi-77788835No ratings yet

- The 100 Global ThinkersDocument96 pagesThe 100 Global ThinkersshahidacNo ratings yet

- Amnesty International Iran ReportDocument77 pagesAmnesty International Iran ReportcaffywNo ratings yet

- Liberian Daily Observer 02/03/2014Document16 pagesLiberian Daily Observer 02/03/2014Liberian Daily Observer NewspaperNo ratings yet

- Arab SpringDocument5 pagesArab SpringPaul DookNo ratings yet

- Martin/Zimmerman. As Noted A Few Hours Ago, Following Imposition of Enormous SocialDocument4 pagesMartin/Zimmerman. As Noted A Few Hours Ago, Following Imposition of Enormous SocialRobert B. SklaroffNo ratings yet

- Sudan Julio 2Document26 pagesSudan Julio 2María CastroNo ratings yet

- 'Not Even The Pharaohs Had So Much Authority': Elbaradei Speaks Out Against MorsiDocument2 pages'Not Even The Pharaohs Had So Much Authority': Elbaradei Speaks Out Against MorsiMohamed AlaaNo ratings yet

- I Can't Breathe: How a Racial Hoax Is Killing AmericaFrom EverandI Can't Breathe: How a Racial Hoax Is Killing AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (13)

- Egypt - Al JazeeraDocument1 pageEgypt - Al JazeeraStefan MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- Rising Up Against The Muslim BrotherhoodDocument2 pagesRising Up Against The Muslim BrotherhoodPhilip Andrews100% (1)

- Syria Troops Kill Protesters in Country's Bloodiest Day of TurmoilDocument16 pagesSyria Troops Kill Protesters in Country's Bloodiest Day of Turmoiladanalejandro2727No ratings yet

- Egyptians Bewildered Over BO Support For MBDocument4 pagesEgyptians Bewildered Over BO Support For MBVienna1683No ratings yet

- mg342 AllDocument24 pagesmg342 AllsyedsrahmanNo ratings yet

- 0307 Cap 014Document1 page0307 Cap 014bernicetsyNo ratings yet

- Sudan Forces Use Teargas on ProtestersDocument4 pagesSudan Forces Use Teargas on ProtestersAnonymous eAKJKKNo ratings yet

- We Are With The People,' Said Ahmed, A Skinny 20-Year-Old Soldier Who Would Not Give His Last NameDocument30 pagesWe Are With The People,' Said Ahmed, A Skinny 20-Year-Old Soldier Who Would Not Give His Last Namepaola pisiNo ratings yet

- Voice Of: Year 2 of Saudi Occupation: A Wake Up Call To The WorldDocument4 pagesVoice Of: Year 2 of Saudi Occupation: A Wake Up Call To The WorldmediaoftruthNo ratings yet

- Front and Center in Ukraine RaceDocument4 pagesFront and Center in Ukraine RacemrsingerNo ratings yet

- The Massacre of Rabaa Between Narration & DocumentationDocument79 pagesThe Massacre of Rabaa Between Narration & DocumentationAmr EbaidNo ratings yet

- Egypt Turmoil News - 29-1-11Document7 pagesEgypt Turmoil News - 29-1-11khanmskhan3No ratings yet

- Alshayeb CampaignDocument6 pagesAlshayeb Campaigntalibsh2No ratings yet

- Inauguration Protesters Vandalize CityDocument12 pagesInauguration Protesters Vandalize CityThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- 02-08-11 Ahead of Mubarak Trial, Egyptian Forces Forcibly Remove Protesters From Tahrir SquareDocument2 pages02-08-11 Ahead of Mubarak Trial, Egyptian Forces Forcibly Remove Protesters From Tahrir SquareWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Special Bulletin September 2013Document4 pagesSpecial Bulletin September 2013Radnička BorbaNo ratings yet

- #iranelection: Hashtag Solidarity and the Transformation of Online LifeFrom Everand#iranelection: Hashtag Solidarity and the Transformation of Online LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Bhmedia23:24 06Document2 pagesBhmedia23:24 06BahrainJDMNo ratings yet

- Liberty Newspost June-13-2011Document87 pagesLiberty Newspost June-13-2011anon_793307646No ratings yet

- Muslim Brotherhood Is Considered As The WorldDocument12 pagesMuslim Brotherhood Is Considered As The WorldMUHAMMED TcNo ratings yet

- Guardian WeekDocument48 pagesGuardian Weekstari makijaveliNo ratings yet

- Bhmedia25 06Document2 pagesBhmedia25 06BahrainJDMNo ratings yet

- Civil Disobedience LD DebateDocument7 pagesCivil Disobedience LD Debateapi-302255740No ratings yet

- (Limpin, Shakti Dev) Mil Q4W2Document5 pages(Limpin, Shakti Dev) Mil Q4W2Shakti Dev LimpinNo ratings yet

- The Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle EastFrom EverandThe Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle EastNo ratings yet

- Morality CrashDocument25 pagesMorality CrashPando Daily100% (8)

- Rovens Lamb LLP: 8 : /) A ,/. RIJVC/+tDocument7 pagesRovens Lamb LLP: 8 : /) A ,/. RIJVC/+tPando DailyNo ratings yet

- ObjectionsDocument4 pagesObjectionsPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Sec Form DDocument5 pagesSec Form DPando DailyNo ratings yet

- The VergeDocument12 pagesThe VergePando DailyNo ratings yet

- Halperin StatementDocument3 pagesHalperin StatementPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Monopsony Labor MRKT CeaDocument21 pagesMonopsony Labor MRKT CeaPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Emails To ErgoDocument26 pagesEmails To ErgoPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Zoumer BrownDocument3 pagesZoumer BrownPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Cory Booker Chabad Neocons by Yasha Levine Nsfwcorp Sept 2013Document14 pagesCory Booker Chabad Neocons by Yasha Levine Nsfwcorp Sept 2013Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Zynga SettlementDocument40 pagesZynga SettlementPando DailyNo ratings yet

- MichaelDevine AmicusCuriaeDocument2 pagesMichaelDevine AmicusCuriaePando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec TellSpec Case Study 09-16-2015Document2 pagesTellspec TellSpec Case Study 09-16-2015Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- U S D C E D O N Y: Lvira OnzalezDocument18 pagesU S D C E D O N Y: Lvira OnzalezPando DailyNo ratings yet

- George Lucas Deposition Techtopus 426-27Document64 pagesGeorge Lucas Deposition Techtopus 426-27Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Uber InsuranceDocument11 pagesUber InsurancePando DailyNo ratings yet

- FeesDocument4 pagesFeesPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec - TellSpec Investor Deck - 09 30 2015 3Document23 pagesTellspec - TellSpec Investor Deck - 09 30 2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Indri Kahn PandoMedia September 25 2015 Offer of SettlementDocument3 pagesIndri Kahn PandoMedia September 25 2015 Offer of SettlementPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec Executive Summary 09-30-2015 3Document1 pageTellspec Executive Summary 09-30-2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec Executive Summary 09-30-2015 3Document1 pageTellspec Executive Summary 09-30-2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec - QA Tellspec - 09 18 2015 3Document4 pagesTellspec - QA Tellspec - 09 18 2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec - QA Tellspec - 09 18 2015 3Document4 pagesTellspec - QA Tellspec - 09 18 2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- MurderDocument27 pagesMurderPando Daily50% (2)

- Tellspec - TellSpec Investor Deck - 09 30 2015 3Document23 pagesTellspec - TellSpec Investor Deck - 09 30 2015 3Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Exhibit 1Document4 pagesExhibit 1Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Tellspec Press Release For TED MED 09-30-2015Document2 pagesTellspec Press Release For TED MED 09-30-2015Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- 10716284262Document16 pages10716284262Pando DailyNo ratings yet

- Gawker Legal MemoDocument32 pagesGawker Legal MemoPando DailyNo ratings yet

- Evolution of the Definition of IndustryDocument21 pagesEvolution of the Definition of IndustryParvathyNo ratings yet

- Security Agency Liable for Guard's ActsDocument2 pagesSecurity Agency Liable for Guard's ActsKRISTINE NAVALTANo ratings yet

- MCB - Offshore Banking Unit (OBU)Document8 pagesMCB - Offshore Banking Unit (OBU)BaazingaFeedsNo ratings yet

- Estate of Pedro C. Gonzales v. Heirs of Marcos PerezDocument48 pagesEstate of Pedro C. Gonzales v. Heirs of Marcos PerezjbapolonioNo ratings yet

- Falklandskrigen - SRP - M.Kocan 3.m 1Document30 pagesFalklandskrigen - SRP - M.Kocan 3.m 1Kerry JohnsonNo ratings yet

- AMA Computer College v. Garcia, April 14, 2008Document20 pagesAMA Computer College v. Garcia, April 14, 2008Felix TumbaliNo ratings yet

- Uy vs. Puzon Case DigestDocument2 pagesUy vs. Puzon Case DigestOjam Flora100% (1)

- G.R. No. 191618Document17 pagesG.R. No. 191618olofuzyatotzNo ratings yet

- Osmeña Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesOsmeña Vs COMELECAjpadateNo ratings yet

- Contract Assingment2 Samprity Kar Bba LLBDocument8 pagesContract Assingment2 Samprity Kar Bba LLBOpen Sea Ever CapturedNo ratings yet

- ProblemDocument2 pagesProblemAnonymous JiiHPiQmiNo ratings yet

- OBLICON - Week 15-16 - INTERPRETATIONDocument9 pagesOBLICON - Week 15-16 - INTERPRETATIONjoyfandialanNo ratings yet

- Finalized Judicial Affidavit - Ernesto Baniqued Branch 100-May 10, 2019, 6P.MDocument14 pagesFinalized Judicial Affidavit - Ernesto Baniqued Branch 100-May 10, 2019, 6P.MVicente CruzNo ratings yet

- History II ProjectDocument12 pagesHistory II ProjectSiddhant BarmateNo ratings yet

- Misterio vs. Cebu State College of Science and Technology 461 SCRA 122, June 23, 2005Document18 pagesMisterio vs. Cebu State College of Science and Technology 461 SCRA 122, June 23, 2005mary elenor adagioNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 12 Political Science Revision Notes Chapter-2 The End of BipolarityDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 12 Political Science Revision Notes Chapter-2 The End of BipolaritygouravNo ratings yet

- AHS Code of Conduct Version 2Document10 pagesAHS Code of Conduct Version 2Dr. Raj ShermanNo ratings yet

- Arcandra Pro TeamDocument10 pagesArcandra Pro TeamDanu EgaNo ratings yet

- Legal and Tax Aspects of BusinessDocument74 pagesLegal and Tax Aspects of BusinessAnagha PranjapeNo ratings yet

- (11a) NOTICE TO VACATE ORDER OF DEFAULTDocument9 pages(11a) NOTICE TO VACATE ORDER OF DEFAULTDavid Dienamik100% (7)

- Katarungang Pambarangay: (Barangay Justice System)Document103 pagesKatarungang Pambarangay: (Barangay Justice System)Jamiah Obillo HulipasNo ratings yet

- Court Reinstates Civil Forfeiture Case Against Bank AccountsDocument4 pagesCourt Reinstates Civil Forfeiture Case Against Bank AccountsJhon NiloNo ratings yet

- Bibliography 2Document3 pagesBibliography 2api-496180442No ratings yet

- Creating a World for Your Quest CampaignDocument20 pagesCreating a World for Your Quest CampaignTrowarNo ratings yet

- Separation of Powers: Concept Note No. 13Document17 pagesSeparation of Powers: Concept Note No. 13Mark GoNo ratings yet

- GSIS LawDocument18 pagesGSIS LawJm EjeNo ratings yet

- MR PenalogaDocument2 pagesMR PenalogaSarj LuzonNo ratings yet

- Vat On Sale of Services AND Use or Lease of PropertyDocument67 pagesVat On Sale of Services AND Use or Lease of PropertyZvioule Ma FuentesNo ratings yet

- Ignorance of Law or Corrupt Officials in Whatcom CountyDocument2 pagesIgnorance of Law or Corrupt Officials in Whatcom CountyDeonet Wolfe100% (1)

- Judicial Review of Religious Conversion CertificatesDocument67 pagesJudicial Review of Religious Conversion CertificatesTetuan Abdullah Hakim & AhmadNo ratings yet