Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Political Economy of Agrarian Movement in Bihar

Uploaded by

kmithilesh2736Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Political Economy of Agrarian Movement in Bihar

Uploaded by

kmithilesh2736Copyright:

Available Formats

Indian Political Science Association

POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AGRARIAN MOVEMENT IN BIHAR

Author(s): APS Chouhan, APS Chauhan and Dinesh Kumar Singh

Source: The Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Oct.-Dec., 2004), pp. 517-530

Published by: Indian Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41856074

Accessed: 08-03-2016 10:15 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Indian Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Indian Journal

of Political Science.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science

Vol. LXV, No. 4, Oct.-Dec., 2004

POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AGRARIAN

MOVEMENT IN BIHAR

APS Chouhan,

Dinesh Kumar Singh

The bloody trail of caste and class carnage continues unabated

in Bihar, cycle of killing and counter-killings continues. In semi- feudal

structure of Bihar caste based private militia of landed class is killing

harijan agricultural labourers. The major carnage against harijan labourers

has occurred at Dumariyan. ( Bhojpur district ) and Miapur village (

Aurangabad district ) Narayanpur , Shankarbigha ( Jehanabad district )

in 2000s. The different faction of CPI(ML) had massacred landlords and

rich peasants. There seems to be no end to this bloody trail of killing

and counter killings which had started three decades ago in the late

1960's and early 1970's with burning of dalit agricultural labourers at

Kargahar, Chhauranano, Gopalpur, Dharampura and Belchhi. This politics

of the brutal form of violence reflects upon the whole dynamics of the

politics of development and democracy which requires a careful analysis.

The importance and relevance of this subject is self-evident to

social scientist of different intellectual persuasion because the myth of.

Indian village as a "sleepy, lethargic and idyllic" place was exploded when

Indian rural village in general and Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal

in particular witnessed violent rural conflict in late sixties. Neither caste

analysis nor class analysis alone will suffice to understand agrarian

conflict. Caste and class dimension of agrarian conflict will be evident

in course of discussion. It is imperative to discuss agrarian relation and

agrarian system that developed during colonial and post colonial period

which will throw light in understanding conflict that is occurring in

Bihar. The classic compilations' of administrator and social scientist

attempted to bring about a much clear understanding of agrarian process

in India in general and Bihar in particular. The British had introduced

there types of revenue settlement. These were permanent Zamindari :

settlement in Bihar, Bengal and Eastern U.P. and parts of Orissa; Ryotwari :

in Bombay, parts of Madras Presidencies, Berar and Assam; and the

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 518

Mahalwari : in United Provinces except Oudh, Punjab and Central

Provinces. The Permanent settlement of land in Eastern India, introduced

by Lord Cornwalis in 1793, confirmed proprietory rights over the land

with zamindars who were only conscious of their own interest and hardly

took interest in improvement of agriculture.

Various acts introduced by the Colonial State for dealing with

tenant - landlord relationship till 1841, tilted in favour of zamindars only

and worsened the position of tenants.2 The acts of 1859 and 1885

introduced to consolidate the position of tenants hardly provided any

relief to the tenants.3 There was wide gap between land revenue paid by

the actual tillers of land and the rent paid to the zamindars . A large

numbers of intermediaries derived income from the landed property

without making any productive effort.4 Many of the zamindars marked

by 4 inability and incompetence 4 created highly ramified set of

middlemen for their estates, in turn, receiving from them proprietory

share of rent. These middlemen not only acquired degrees of rights

on the land itself but also exploited poor peasantry leading to

perennial source of agrarian tension. 5

In brief rent enhancement, unauthorised exactions, evictions and

other kinds of oppression against the tenantry continued, more or less,

throughout the period6. The landlords and their agent extracted maximum

surplus in the form of extra legal and illegal cesses or levying abwabs,

Salami money paid at the time of transfer of occupancy holdings and

vicious system of Corvee known as begar. This settlement was also

marked by deterioration in agricultural production .7 As far as agrarian

classes are concerned, prior to 50 's, there had grown up in Bihar an

Intricately stratified system of relation ofpeopletoland:TheZamindar,

the tenure holder, the occupancy ryot, the non-occupancy ryot, the under

ryot and the Mazdoor.8,

II

In fact the agrarian relation varied from one region to another

region depending upon nature of revenue settlement. The nature of

agrarian relation in Bihar was quite different from that of Maharastra,

Punjab and Western U.P. One must not overemphasize the relationship

between land tenure system and agrarian relation which in turn, more or

less, shaped the nature of the peasants movement in different parts of

India. The Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha9 led by Swami Sahajanand

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 519

Saraswati advocated for the abolition of zamindari system in 1930's and

1940's. The peasant movement in Maharastra and Western U.P. was

directed against money lenders. The Tebhaga Movement10 in Bengal was

led by the share-croppers against Jotedar for the reduction of the hare

of he proprietor from one-half of the crop to one-third. Thus the type of

land tenure system, in a general sense, influenced agrarian relations and

issue and demands to be taken up by the peasant movements.

In Bihar, the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha led by Swami

Sahajanand Saraswati struggled to dismantle the permanent settlement.

The movement was joined by the Congress Socialists Party led by Jaya

Prakash Narayan, the Communist Party of India led by Karyanand

Sharma. The movement forced the Congress Party, which came into power

briefly in 1937, and then in 1946, to address itself to the question of

changing the agrarian system through legislation.1 1 The election

manifesto of the Congress party in 1946, for first time , talked of agrarian

reform, but after winning election on the basis of this manifesto, it moved

at slow pace in the direction of abolishing zamindari. Meanwhile the

peasants agitated on the issue of Bakasht lands during 1939 to 1945 in

south Bihar.12

Land reforms be discussed because it would enable us to

understand not only agrarian relations but nature of agrarian conflict.

Bihar was first state to pass the Bihar Abolition of Zamindari Bill to

abolish the zamindari system. It was then amended and published as the

Bihar Abolition of Zamindari Act, 1948, only to be repeated and replaced

by the Bihar Land Reform Act, 1950, the validity of which was finally

upheld by the Supreme Court in 1952.,3Apart from it, the Bihar

Legislature enacted land reform legislation dealing with ceiling on land

holding, consolidation of holding and provision relating to minimum

wages for agricultural labourers.

The zamindars vehemently opposed at entry stage of the various

provisions of land reform bills causing inordinate delay and dilutions

in final enactments inside the state legislature. 14 Commenting upon it,

A.N.Das writes, " It was opposed in political forum by no less a

person than Dr Rajendra Prasad, in the mass media, and in the

courts by the ' Maharajadhiraj ' of Darbhanga,

through a variety of extra-parliamentaiy actions by the likes of the

' Rajas ' of Ramgarh, Kursela and other large and petty zamindars. ",5

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 520

S.K .Sinha, while participating in debate inside legislature, has opined

that "J tell you that you are at the crest of volcano, the volcano may

burst at any moment It is only to save you from destruction that

I have brought this resolution 16 The zamindari Abolition Act

abolished zamindars but the same persons continued to maintain

their hold over the village power structure. The act has been

formulated and framed in such way that benefited zamindars. There

was sufficient loopholes in the act. This shows the strength of

economic and social power enjoyed by the zamindars.17

The Bihar Tenancy Act, 1885 was amended in 1955 and

subsequently in 1970. Certain exception and exemption included in

the act gave landlords a lot of scope to manoeuvre and manipulate

and even to prevent under-raiyats to acquire occupancy rights. I8c

Ladejinsky, in his field trip to Kosi Area in Bihar in 1969, found that

the condition imposed on share-croppers was probably of its worst

kind in the country 9 The working group on Land Reforms notes,

practice

from acquiring rights in lands ".20 This fact was confirmed by

scholars 2,and another governmental committee 22 on Land Reforms .

Apart from it, Bihar Land Reforms ( fixation of ceiling area and

acquisition of surplus land) Act passed in 1961 permitted every

land owner to transfer within six months from the commencement of

the act, any land held by him to his son, daughter , grandchildren

or any other heir . 23 In nutshell we can say that all these Acts

failed to bring change in the agrarian set-up of Bihar. This has

been concluded by the working group on Land Reforms of the

National Commission on Agriculture : " By their abysmal failure to

implement the laws , the authorities in Bihar have reduced the whole

package of land reform measures to sour joke

land -owners do not care a tupp nance for the administration ." 24

The agrarian social structure and agrarian relation , in post

independent India, varies from region to region. Wertheim characterized

the agricultural policy of the government as " betting on the strong "

25 Which created regional imbalance. There is capitalist type of

farming in Punjab, Haryana and parts of western U. R while in

Bihar and West Bengal there is semi- feudal, semi-capitalist mode of

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 521

production.26 The feature of semi-feudal mode of production in Bihar,

according to Pradhan H. Prasad, is reflected in landowners

approaching the process of production and distribution with a view

to strengthening their control over the masses, resulting in a set-up

where an indissoluble bond between direct producer and his landlord

is maintained by resort to "production relation" characterized by

two modes of appropriation, share-cropping and usury. This results

in semi- servile condition of living and low level of consumption,

and hence mass poverty and low productivity of land and labour

, under- utilization of resources and almost negligible investment in

the agricultural sector.27

Ill

The various measures of land reforms, rural development

and green revolution benefited upper backward caste (or intermediate

agrarian castes: Yadavas, Kurmi,and Koeri) in Bihar, Yadavas, Kurmis

and Koeris were, in pre-independence period, mostly tenants. The

most numerous and relatively affluent among backwards Yadavas

and Kurmis, during 1920's, protested against social oppression by

upper caste. Later on Koeris 28 joined the movement. Triveni Sangh

was their political outfit. The social movement started by these

backward caste turned into economic conflict between upper-caste

landlords and lower caste tenants. In post independent period,

they benefited from various land reforms measures, green revolution

and rural development. They improved and consolidated their

economic position . They, once constituted the leading core of the

old Kisan Sabha movements, emerged as landlords, middle and

rich peasants.

These upper backward castes not only consolidated their

economic power but also emerged as politically conscious force in

Bihar. In the late 1970's Karpoori Thakur Ministry's reservation

policy are indicative of a sea change in the structure of Bihar

political economy . Observing on social change in Bihar, Harris W.

Blair writes: " The Forwards or twice born" caste groups that had

been dominant in Bihar since independence and before are being

replaced by the ' backwards caste ' as the dominant stratum in the

state."29 The hegemony and dominance of twice born castes was

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 522

challenged by emerging upper backward castes. Dalits became

conscious and politically assertive. They began to be organised by

different faction of CPI(ML). Their demands was centred on the

various issues of rural social and class structure ie. struggle for

honour, opposition to oppression and exploitation, enforcement of

minimum wages laws, recognition of share- cropper's right and

abolition of bonded labour.30

The emerging backward castes are facing a challenge from

below. The rich peasants from upper backward caste is very

aggressive. It is a rising class. It is fighting two battles, socially

and politically it is struggling against the upper castes and

economically it is facing the dalits agricultural labourers and share-

croppers who are now organizing themselves. Commenting upon

it Aran Sinha says that the major outrages against harijan sharecroppers and agricultural labourers were committed by both socalled backward castes of Kurmi and Yadavas and upper castes

landlords. This rich peasants from upper backward castes have

become more aggressive, ruthless and exploitative than upper caste

landlords. They have transformed themselves into Kulaks. It does

not mean that upper castes landlords have in any become less

ruthless or exploitative. 31

Now it will be pertinent to point out caste and class

interrelationship in Bihar . Gail Omvedt32 felt that in India there are

three classes: the rich peasants, the middle peasants and the poor

peasants and agricultural labourers. The rich farmer, according to

her, includes capitalist farmers, capitalist landlords, and feudal

landlords. In caste term traditional feudal castes: Brahmans, Rajputs,

and middle kisan castes such as Marathas, Jats, Lingayats, Kammas,

Reddis, Vokkaligas etc come under the category of rich farmers. These

Kisan castes are dominant in those area where capitalist development

has taken place in agriculture. The poor peasant and agricultural

labourers includes mostly dalits, adivasis, muslims and traditional

middle castes. We must look at caste and class hierarchy in Bihar.

In caste terms , landlords included the upper castes and upper

backward castes such as Yadavas, Kurmis and Koeris. Rich peasants

belong to both upper castes and upper backward castes. The

middle peasants include not only upper castes, upper backward

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 523

castes but also scheduled castes and tribes. The poor peasants

and agricultural labourers have in their ranks the great majority of

the backward castes and almost the entire harijan and adi vasi

population.33

If we closely observe development of agrarian unrest, it

shows that class factor is the basic factor underlying these

developments. But many social scientists analysing these phenomena

may prefer to see them in caste rather than class terms. When

scholars throw their finely sociological nets into the stagnant waters

of Bihar's society, they draw out not class but the familiar .fishes

of caste. But this is half the story. The discontent among dalits

and rural poor could no longer be managed , a state of violence

erupted. In 1970's the major outrages against harijan labourers in

Karahgar, Belchi, Pathadda, Chhauradano, Gopalpur, Dharampura etc

are bloody testimonies of class war going on in Bihar.34

The South Bihar (Bhojpur, Buxar, Rohtas, Kaimur, Jehnabad,

Patna, Gaya, Nalanda and Aurangabad) has witnessed a series of

agrarian conflict in its caste and class dimension. The nature of

conflict is entirely different from conflict that is taking place in

Purnea, Bhagalpur and Champaranpur district. The diara area of

Bhagalpur-Munger hills and forests of Kaimur range and the

Himalyan terrain of West Champaran and malaria- infested tracts of

trans -Kosi* Purnea are characterized by, in spite of overall pressure

of population, relatively low population density and less intensive

agriculture. Lack of well established agrarian hierarchy, the weak

nature of peasant caste and feudal oppression were common

features of this region. It led to the emergence of roving rebel

gangs of erstwhile peasants. 35

The main area of agrarian conflict is confined to Southern

districts of Bihar. The Sone canal system, in southern districts,

provided irrigation facility that led to increase in* agricultural output

and income of zamindars. The improved irrigation facility and

improved commercialisation of farming of this region provided

material condition of agrarian unrest. 36 These regions has taken

lead over other region in average yield quintal hectare for rice

and wheat. 37 In short, on the relative scale of the level of

development of agriculture, southern Bihar is far ahead than other

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 24

region. 38 These region witnessed some package of green revolution.

It increased agrarian tension. The Home Ministry of Government of

India made a study in 1969 on causes and nature of agrarian

tension. It came to the conclusion that the green revolution, instead

of being an instrument of social transformation, became an instrument

of social oppression. It has widened disparities between relatively

few affluent farmers and the large body of small landholders and

agricultural workers. In consequence it has generated social tension.39

Thus Bihar witnessed , in late 1960's and 1970's, a numbers of

sporadic agrarian movements and the setting up of small

organisations. In these movements, main participants were poor peasants

, share-croppers and agricultural labourers belonging mainly to the

Harijan- Adivasi section fighting not absentee landlordism as in the

zamindari period but the new rich peasantry: the upper backward/

intermediary agrarian castes which had become more exploitative,

ruthless and oppressive.40

A strong wave of spontaneous, sporadic and largely

unorganised agrarian movements of the poor and landless peasants

occurred in Bihar since late 1960's. They have come under some

ort of ideological guidance of one faction or the other of the

CPI(ML) as in Musahari (Muzaffarpur), Purnea and Chauri, Ekwari

and Chapra (Bhojpur district). These movements have been met by

tremendous repression by both the landlord and the state.41 These

peasant movements were also called first phase of the Naxalite

Movement in Bihar. It rejected the possibility of peaceful solutions to

socio- economic problems and in turn resorted to violence. The first

phase of the Naxalite Movement was characterized as mindless

violence.

Since 1980's political analyst have noted qualitatively new

aspect of the naxalite movements as an important force in left

politics. The new politics of left range from various factions of

CPI(ML), the most important being the Liberation, and party unity

groups, guerrilla groups like the Maoist Communist Centre(MCC),

mass organisation like IPF, and Mazdoor Kisan Sangram

Samiti(MKSS). Various factions of CPI(ML) have distinct organisational

forms. There has been rivalry between them on carving out spheres

of influence. These groups has been spreading not only in the areas

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 525

of original Naxalite activity like Bhojpur but also to Southern Bihar

and tribal Jharkhand region. 43 In 1982, in its document entitled 4

Notes on Extremist Activities- affected Areas', the Bihar Government

reported that as many as 47 out of a total of 587 blocks, spread over

14 districts, were affected by the communist extremist movement. It

has grown enormiously in the face of the corrupt, casteist and

incompetent administration of Bihar.43

IV

Violence, bloody clashes and tough resistance have become

mode of social intercourse in Bihar. The cycle of caste- class violence

continues unabated in Bihar, The Southern Bihar has witnessed the

emergence of caste-based landlord's Sena.44 These Senas has been

constituted to suppress agrarian movement. As Arun Sinha has

pointed out " The major feature of social as well as political life is

the prevalence of the language of force. " 4;>CPI(ML) Liberation Group's

position, on issue of violence, is conditioned by the socio-economic

condition prevailing in Bihar. It states :

" Everywhere in Bihar, it is landlords who are armed, they

derive a sadistic pleasure, burning their houses and raping their

women. Secondly, by any human logic whatsoever, the rural poor

cannot be denied their right to organize their own resistance forces

to counter the attacks of landlord armies. Thirdly, if peasant struggle

takes violent forms in Bihar, the root must be sought in the forms of

oppression ." 46

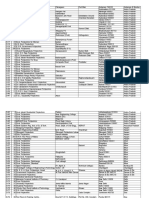

Table-1 Major Caste Senas of Bihar

Name of Caste Year of Operational

Sena

Kuer Sena Rajput 1979 Bhojpur, Rohtas

Kisan Suraksha Kurmi 1979 Patna, Jehanabad,

Samiti

Bhoomi Sena Kurmi 1983 Patna, Nalanda

Lorik Sena Yadav 1983 Patna, Jehanabad

Brahmarshi Sena Bhumihar 1984 Bhojpur, Patna,

Jehanabad

Kisan Sangh Rajput, 1984 Palamu

Brahmin

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 526

Sunlight Sena Rajput 1989 Palamu, Gaya,

Sawarna Liberation Bhumihar 1990 Gaya, Jehanabad

Front

Kisan Sangh Bhumihar 1990 Patna, Bhojpur

Kisan Morcha Rajput 1989-90 Bhojpur

Ganga Sena Rajputs 1990 Bhojpur

Ranvir Sena Bhumihar 1994 Bhojpur, Patna,

Jehanabad,

Aurangabad,

Source: Prakash Louis. "Class War Spreads to New Areas". EPW, Vol. XXXV,

No 26 , June 24-30, 2000

The Landlords and rich peasants have formed their own caste

based sena in Southern Bihar.lt needs a careful analysis. One group

of political analyst argue that the senas came into existence as

response to naxalite violence. Other opinion considers that the

emergence of Sena is fall out of the green revolution. The increased

production due to green revolution widened gap between rich peasants

and agricultural labourers. When dalit labourers demanded a greater

share in the production, rich peasants formed Sena to suppress

them.47 A more oppressive rich peasantry is giving up pretences of

patronage. It is interested only in exploitation. As A.N. Das writes:

"The system of patronage - clientelism itself was broken forever

and socio - political assertion through the exercise of sheer brute

force took its shape ."48

AS we have discussed earlier , in South Bihar a semifeudal society has led to rise to ruthless oppression, violent revolts

and resistance. Killing and counter - killing is going on. The bloody

trail of caste and class carnage continues unabated in Bihar. In

2000's the Ranvir Sena the outlawed private militia of the upper

caste landlords killed six supporters of CPI(ML) at Dumariyan

village in Bhojpur district. The same sena had massacred more

than 35 people of Yadava and Pas wan caste at Miapur village in

Aurangabad district. The killings was obviously in retaliation to

senari and Afsara carnages. At Senari in Jehanabad 34 bhumihars

had been massacred by the Maoist Communist Centre on March 18,

1999. The Ranvir Sena killed 22 dalits and backward castes in

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 527

Shankarbigha village in Jehnabad district on Jan25,1999. They again

massacred 11 and 12 dalits in Narayanpur village ( Jehnabad

district) and Sendani (Gaya district). 49

Violence , massacre, ruthless oppression and resistance have

become feature of semi-feudal society of Bihar. The ruthless and

exploitative rich peasantry and landlords is attempting to establish

their dominance and hegemony through brute use of force. Dalit

share-croppers and agricultural labourers are violently resisting to

overthrow oppressive and hegemonic structure. They are asserting

their identity. The unfolding of class and caste contradictions are giving

rise to violent revolt, resistance and massacre. The roots of agrarian

violence lies in the semi-feudal political economy of Bihar which is

ruthlessly exploitative, castiest and oppressive in nature, even at the doors

of the twenty-first century.

REFERENCES :

1. Please see for detailed discussion on aspects of colonial agrarian

system: Baden-Powell, B.H, Land Tenures of British India, OUP,

Calcutta, 1882; Daniel, Thomer, Agrarian Prospect in India,

Allied Publishers N. Delhi, 1976; Frykenberg (ed), Land Tenure

and Peasant in south Asia. Manohan New Delhi, 1977; Guha

Ranjit, A Rule of Property in Bengal. Mouton, Paris, 1963;

Buchanan, Francis, Report on Shahabad. in 1811-12. Patna, 1922;

and also by the same auther -An account of District of Purnea

in 1809-10. Patna. 1928: Sinha, R.N, Bihar Tenantry. 1785-1833.

Bombay, 1968; Bhowani , Sen, Evolution of Agrarian Relations

in India. PPH, 1962.

2. Sinha, R. N,op.cit, pp. 1 04- 1 2

3. Ojha, G, Land Problem and Land Reforms : A study with

reference to Bihar , Sultan Chand and sons, New Delhi, P. 35

4. ibid, pp.46-47

5. Das. A.N. Agrarian Unrest and Socio- economic Change in Bihar,

1900-1980. Manohar, New Delhi, 1983, PP .24-27

6. Sinha, R N, op. cit, p.47

7. Ojha, G, Land Problem and Land Reforms: A Case Study of

Champaran. NEW DELHI, 1978, PR 45-68

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 528

8. Jannuzi , F. T, Agrarian Crisis in India, the Case of Bihar,

New Delhi, Sangam Books, 1974, pp. 10-1 1.

9. Walter Hauser, The Bihar Provincial KisanSabha, 1929-1942.

A Study of An Indian Peasant Movement, A Dissertation

submitted to the Faculty of the Social Sciences in Candidancy

for the degree of Ph. d, Deptt. Of History, Chicago, Illinois,

Sept, 1961. also see Das, A. N, op. cit

10. Harnza Alavi, " Peasant and Revolution " in A.R. Desai(ed),

Rural Sociology in India, Popular Prakashan, Bombay, 1969,

p.413.

11. Das , A.N. The Republic of Bihar, Penguin Books, New Delhi

, 1992, p. 3512.Das. A.N, Agrarian and Socio-economic Change

in Bihar, op. cit, for detail see Gupta, Rakesh, Peasant Struggles;

A Case Study of Bihar, Ph.D Thesis , J. N. U , New Delhi, 1978.

'and also see Hauser Walter, op. cit, Bakshat Land is Holding

which is not cultivated by tenants and it is not personal property

of the landlords.

13. Jannuzi, F. T, op.cit, pp. 12- 13.

14. Sir C.P. N. Singh and Syamanandan Sahay, quoting several

examples, pleaded for the retention of the zamindari system.

See. Legislative Assembly Debates from 1946 to 1947.

15. Das, A.N, The Republic of Bihar, op. cit, p.35.

16. Bihar Legislative Assembly Debate, 26 July, 1946.

17. Ojha, G, op.cit, pp.52-55.

18. Pandey, A.R, " Tenancy Reforms for share-croppers and

homeless Tenants in Bihar Social Science Probyn, March,

1986.

19. quoted in ibid.

20. Bandhopadhyay, " Agrarian Relations in Two Bihar Districts:

A field survey, Mainstream, vol XI, No.40,1973

21. Koshy, V.C " Land Refonms in India Under the Plans"'

Social Scientist, July 1974, p. 52.

22. India, Planning Commission, Implementation of Land

Reforms: A Review by Land Reforms Implementation Committee

of the National Development Council, New Delhi, 1 966, pp 279281.

23. Ojha, G, op. cit.p.29.

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Political Economy Of Agrarian Movement In Bihar 52M

24. Bandyopadhyay,D , op.cit.

25. Wertheim ,W. F, " Betting on the strong " , in Desai , A.R ,

op. cit pp.894-903.

26. Pradhan H Prasad, " Production Relation : Achilles ' Heel of

Indian Planning " EPW, vol.8, No. 19, 1973.

27. Ibid.

28. Kalyan Mukheree and Rajendra Singh Yadav, Bhoipur:

Naxalism on the Plains of Bihar, New Delhji, Radha Krishna

Prakashan, 1980

29, Blair W Harry , " Rising Kulak and Backward Classes in

Bihar, Social Change in the late 970 's" EPW, vol.xv, NO.

2, Janl2, 1980

30. Ibid see. Also Das ,A.N, op.cit, p.253

31. A run Sinha, " Adavancing class interests in the name of

caste" EPW, Apri 22, 1978; Also see Arvind N Das, " Class

in itself Caste for itself social articulation in Bihar , "

EPW, vol. Xix, No. 37, 1984; Report from flaming fields of

Bihar, A CPI(ML) Document, Sree Art Press, Ramnath

Majumdar Street, Calcutta, Aug, 1986, p.47

32. Gail Omvedt," Class, Caste and Land in India: An

Introductory Essay" Teaching Politics, vol. VI, No, 3 &4, 1980.

33. Report from flaming fields of Bihar, A CPI(ML) Document,

op.cit., pp. 46-47.

34. Das A.N, op.cit, EPW, vol. XIX, No.37,15 Sept, 1984

35. Das A.N, The Republic of Bihar, op. cit, pp.33-34; Report

from flaming fields of Bihar, A CPK ML) Document, op.

cit, p. 7

36. Mukherjee Kalyan and R. S Yadav, op. cit. p.38

37. Dasgupta, Biplab, The New Agrarian Technology and India,

United Nation, Geneva, 1977, p.29.

38. Framework Action Plan for foodgrain production, Report of

the Task Force, Planning Commission, Government of India,

March, 1988,pp.4-l 1; also see See. Misra, S K, valuation of

Public Policies for Agricultural Development in Less

Developed Region, I.l.T, Kharagpur, 1985, pp.214-15.

39. cited in Sachidanand, Social Dimension and Agnculiirai

Development, National Publishing House, Delhi, 1972

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Indian Journal of Political Science 530

40. Das, A.N , Agrarian Unrest and Socio-economic Change in

Bihar, op. cit, p.222

41. Ibid, pp.230-232.

42. Das, A.N, The Republic of Bihar, op.cit, pp. 109-1 10

43. Ibid, p. 107

44. " Bihar, Peasant , Landlords and Dacoits'' EPW, vol,xxi,

Aug30,1986

45. cited in Das A.N, The Republic of Bihar, p. 107

46. Ibid, p. 108.

47. Prakash Louis, op.cit,

48. Das A.N, The Republic of Bihar, op.cit, p,73

49. Prakash Louis, op. cit,

This content downloaded from 137.154.19.27 on Tue, 08 Mar 2016 10:15:13 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Tata Motors National Tieup PVT WorkshopDocument290 pagesTata Motors National Tieup PVT WorkshopKundan ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Format - Hum - Role of MGNREGA On Women Empowerment - A Case Study of The Mangalapuram Gramapanchayat of Thiruvananthapuram District, KeralaDocument8 pagesFormat - Hum - Role of MGNREGA On Women Empowerment - A Case Study of The Mangalapuram Gramapanchayat of Thiruvananthapuram District, KeralaImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Unit 31 PDFDocument14 pagesUnit 31 PDFnazmulNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Democratization in Korea PDFDocument201 pagesThe Politics of Democratization in Korea PDFGigi CostelusNo ratings yet

- Banned Controversial Literature and Political Control in British India 1907-1947 (1976)Document322 pagesBanned Controversial Literature and Political Control in British India 1907-1947 (1976)VishwaMohanJha100% (1)

- Unpaid Unclaimed 2010A 14Document3,003 pagesUnpaid Unclaimed 2010A 14Siddharth KumarNo ratings yet

- Bombay Deccan and KarnatakDocument245 pagesBombay Deccan and KarnatakAbhilash MalayilNo ratings yet

- Accurate DatabaseDocument18 pagesAccurate DatabaseVikramNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Staying: Social Movements and Land Rights Politics in PakistanFrom EverandThe Ethics of Staying: Social Movements and Land Rights Politics in PakistanNo ratings yet

- Batliwala 2007 EmpowermentDocument14 pagesBatliwala 2007 EmpowermentLucre C IribarNo ratings yet

- Export - Import - 139Document24 pagesExport - Import - 139EconaurNo ratings yet

- Nine Decades of Indian Communist MovementDocument67 pagesNine Decades of Indian Communist MovementSunit Singh100% (1)

- BriefHistoryOfMCCIandCPIMLPW Eng OCR PDFDocument71 pagesBriefHistoryOfMCCIandCPIMLPW Eng OCR PDFPremNo ratings yet

- Dusk, Dawn and Liberation: A Historical Fiction on the Liberation Struggle of BangladeshFrom EverandDusk, Dawn and Liberation: A Historical Fiction on the Liberation Struggle of BangladeshNo ratings yet

- OMAR Series Urdu Hindi Dubbed LinksDocument28 pagesOMAR Series Urdu Hindi Dubbed LinksSyed Muhammad Hasan Bilal100% (1)

- Peasantry Their Problem and Protest in Assam (1858-1894)From EverandPeasantry Their Problem and Protest in Assam (1858-1894)No ratings yet

- Liberalism in Empire: An Alternative HistoryFrom EverandLiberalism in Empire: An Alternative HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Caste Politics in BiharDocument6 pagesCaste Politics in Biharaditya_2kNo ratings yet

- Tribal Movements in India After 1947Document9 pagesTribal Movements in India After 1947Kavya SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Naxalite Movement's Impact and Factionalism in Central BiharDocument14 pagesThe Naxalite Movement's Impact and Factionalism in Central BiharBrian GarciaNo ratings yet

- All India Seminar On The Impact of Naxalbari On Indian Society: Achievements and ChallengesDocument56 pagesAll India Seminar On The Impact of Naxalbari On Indian Society: Achievements and ChallengesNilton Anschau JuniorNo ratings yet

- Rise of Backward Classes in Post-Independence IndiaDocument9 pagesRise of Backward Classes in Post-Independence IndiaKumar Deepak100% (1)

- Development Research in BiharDocument483 pagesDevelopment Research in BiharAvishek RanjanNo ratings yet

- Books by Socialist LeadersDocument63 pagesBooks by Socialist Leadersashok kulkarni100% (1)

- Programm Path and Constitution by CPI (ML) ND PDFDocument92 pagesProgramm Path and Constitution by CPI (ML) ND PDFVenkateswarlu ChittipatiNo ratings yet

- Peoples March April May JuneDocument40 pagesPeoples March April May JunenpmanuelNo ratings yet

- Resources Against Communalism - IndiaDocument162 pagesResources Against Communalism - IndiaSandeep Samwad100% (1)

- The Anti-Khoti Movement in Konkan Region PDFDocument62 pagesThe Anti-Khoti Movement in Konkan Region PDFAmit DhekaleNo ratings yet

- Communist Party of IndiaDocument10 pagesCommunist Party of IndiaZain SuhailNo ratings yet

- Shivaji CeremonyDocument3 pagesShivaji CeremonyplagadzNo ratings yet

- Rise of Popular MovementsDocument10 pagesRise of Popular Movementsjalnidh44% (9)

- Land Reforms in BiharDocument26 pagesLand Reforms in BiharChitragupta SharanNo ratings yet

- The Chipko Movement - Non-Violent Resistance to DeforestationDocument5 pagesThe Chipko Movement - Non-Violent Resistance to DeforestationKUSHAL100% (1)

- Emergence of Critical & Cultural Theories in Mass CommunicationDocument6 pagesEmergence of Critical & Cultural Theories in Mass CommunicationRajesh Cheemalakonda100% (3)

- Coalition Governments in IndiaDocument3 pagesCoalition Governments in IndiaAshashwatmeNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Gandhi's Civil Disobedience MovementDocument6 pagesIntroduction to Gandhi's Civil Disobedience MovementAbhijith S RajNo ratings yet

- The British Raj and India British Colonial Influen PDFDocument22 pagesThe British Raj and India British Colonial Influen PDFAnil Kumar BangaloreNo ratings yet

- Social MovementsDocument18 pagesSocial MovementsJananee RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- Fascist Trends in Indian MediaDocument60 pagesFascist Trends in Indian Mediapramodsharma_1976402350% (2)

- Romila Thapar LectureDocument4 pagesRomila Thapar LectureemasumiyatNo ratings yet

- Sumit Guha Environment and Ethnicity in India 1200 1991 Cambridge University Press 1999 PDFDocument235 pagesSumit Guha Environment and Ethnicity in India 1200 1991 Cambridge University Press 1999 PDFAdithya RaoNo ratings yet

- Election Law in India AnalysisDocument110 pagesElection Law in India AnalysisIshaan HarshNo ratings yet

- The Role of Women in Chakma CommunityDocument10 pagesThe Role of Women in Chakma CommunityMohammad Boby Sabur100% (1)

- The Subaltern Critique of Elite Historiographies in IndiaDocument4 pagesThe Subaltern Critique of Elite Historiographies in IndiaAnkita PodderNo ratings yet

- India After IndependenceDocument11 pagesIndia After IndependenceAmitNo ratings yet

- Government and Politics in North East India: An In-Depth GuideDocument99 pagesGovernment and Politics in North East India: An In-Depth GuideImti LemturNo ratings yet

- Path To Mordenisazation (China)Document29 pagesPath To Mordenisazation (China)Pranesh raamNo ratings yet

- An Anthropologist Among The Historians and Other Essays: OxfordDocument3 pagesAn Anthropologist Among The Historians and Other Essays: OxfordArmageddon Last100% (1)

- Extremist PhaseDocument3 pagesExtremist PhaseBashir Ahmad DuraniNo ratings yet

- Sikkim - The Merger With IndiaDocument14 pagesSikkim - The Merger With IndiaIslam IslamNo ratings yet

- Democratic Rights Movement in India - PapersDocument156 pagesDemocratic Rights Movement in India - PapersSatyam VarmaNo ratings yet

- Tribal DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTribal DevelopmentDivyaNo ratings yet

- Role of Chiang Kai Shek and The Kuomintang Shreya Raulo Final Sf0118050 Semster 3 History ProjectDocument16 pagesRole of Chiang Kai Shek and The Kuomintang Shreya Raulo Final Sf0118050 Semster 3 History ProjectShreya Raulo100% (1)

- Top 6 Peasant Movements in India - Explained! Emphasis On Tebhaga MovementDocument20 pagesTop 6 Peasant Movements in India - Explained! Emphasis On Tebhaga MovementRavi shankarNo ratings yet

- Rise of Radical PoliticsDocument11 pagesRise of Radical PoliticsaccommodateNo ratings yet

- Civil Society and Democratic ChangeDocument17 pagesCivil Society and Democratic ChangenandinisundarNo ratings yet

- The Revolutionary Movement in India - EssayDocument14 pagesThe Revolutionary Movement in India - EssaymitulNo ratings yet

- Feminism in Socialist Countries - Assignment Sem 6Document5 pagesFeminism in Socialist Countries - Assignment Sem 620527059 SHAMBHAVI TRIPATHINo ratings yet

- 14 Chapter 2Document56 pages14 Chapter 2Waheed AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Naxal WomenDocument2 pagesNaxal WomenRishabh SainiNo ratings yet

- After A Century and A Quarter by G.S GhuryeDocument185 pagesAfter A Century and A Quarter by G.S Ghuryenrk1962100% (1)

- Samyukta Maharashtra MovementDocument3 pagesSamyukta Maharashtra MovementAbhas VermaNo ratings yet

- India's Internal Security - Namrata GoswamiDocument140 pagesIndia's Internal Security - Namrata Goswamimossad86No ratings yet

- Development of Urban Villages in Delhi - 2013Document148 pagesDevelopment of Urban Villages in Delhi - 2013kmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Israel Is Trying To Change The Laws of War - Fair ObserverDocument8 pagesIsrael Is Trying To Change The Laws of War - Fair Observerkmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Indian Communists Criticise Armed Economism in BiharDocument7 pagesIndian Communists Criticise Armed Economism in Biharkmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Public Private PartnershipDocument9 pagesPublic Private Partnershipkmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- List Hindi JournalsDocument2 pagesList Hindi Journalskmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- 12 Dates of Valentine'S - #LBB's Picks For Your Hot Date - Little Black Book, DelhiDocument5 pages12 Dates of Valentine'S - #LBB's Picks For Your Hot Date - Little Black Book, Delhikmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- #LBBBestOf Thali Meals in Delhi and Around - Little Black Book, DelhiDocument6 pages#LBBBestOf Thali Meals in Delhi and Around - Little Black Book, Delhikmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- 848082154RP15 Kujur NaxalDocument18 pages848082154RP15 Kujur NaxalShreesh ChandraNo ratings yet

- Service Act 1992Document65 pagesService Act 1992kmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Liberation v1n2 67decDocument47 pagesLiberation v1n2 67deckmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Liberation v1n1 67novDocument69 pagesLiberation v1n1 67novkmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Sin and ScienceDocument83 pagesSin and ScienceSatya Narayan50% (2)

- Opportunity at RiskDocument88 pagesOpportunity at RiskABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- Rio TintoDocument12 pagesRio Tintokmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Digital Imperialism Through Online SocialFinancial Networks PDFDocument8 pagesDigital Imperialism Through Online SocialFinancial Networks PDFkmithilesh2736No ratings yet

- Top Indian movies of the weekDocument2 pagesTop Indian movies of the weekArzooReyNo ratings yet

- Regional ImbalanceDocument20 pagesRegional Imbalancesujeet_kumar_nandan7984100% (8)

- Macro ClassDocument15 pagesMacro ClassRaj GoyalNo ratings yet

- Caste-wise voter data from multiple polling boothsDocument32 pagesCaste-wise voter data from multiple polling boothssoumya rathaNo ratings yet

- Important Contacts No.Document19 pagesImportant Contacts No.Arvind JangirNo ratings yet

- Rude Awakenings WebDocument335 pagesRude Awakenings WebzendomeNo ratings yet

- Revised District Wise Contact Detail For GVRSDocument5 pagesRevised District Wise Contact Detail For GVRSankitgautamsc1234433No ratings yet

- NCTE Affiliated UniversityDocument26 pagesNCTE Affiliated UniversityRanjan Nihar NandaNo ratings yet

- 2 YearDocument15 pages2 YearPrince GargNo ratings yet

- Tata Indicom COCO OutletsDocument30 pagesTata Indicom COCO OutletsShuie BlackNo ratings yet

- Problems of Labour Migration in BiharDocument5 pagesProblems of Labour Migration in BiharMAO YELLAREDDYNo ratings yet

- Code-5 GeographyDocument17 pagesCode-5 GeographySakshi PriyaNo ratings yet

- A List of All Doctors of The Government of BiharDocument32 pagesA List of All Doctors of The Government of BihargauravNo ratings yet

- Modern History of Bihar 41 PDFDocument21 pagesModern History of Bihar 41 PDFHago KrNo ratings yet

- TSI 2012 Final Qualifier ListDocument5 pagesTSI 2012 Final Qualifier ListRahul PatilNo ratings yet

- Dinesh Kumar MehrotraDocument20 pagesDinesh Kumar MehrotraRajeev JhaNo ratings yet

- AES WINNERS 2014 - 15 - Science Olympiad FoundationDocument3 pagesAES WINNERS 2014 - 15 - Science Olympiad FoundationG KumarNo ratings yet

- ILFS Report BiharDocument155 pagesILFS Report Biharsouravroy.sr5989No ratings yet

- PolytechniccollegesDocument29 pagesPolytechniccollegesRikkysuraj Dattatray MoreNo ratings yet

- Fianl Provisionally AcceptedDocument128 pagesFianl Provisionally AcceptedJames WilliamsNo ratings yet

- History of Jharkhand MovementDocument4 pagesHistory of Jharkhand MovementbibinNo ratings yet

- OutputDocument7 pagesOutputSayan MondalNo ratings yet

- Gandhi 2Document3 pagesGandhi 2saiNo ratings yet

- Kalyan PurDocument111 pagesKalyan PurAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- Bihar: Delimitation CommissionDocument101 pagesBihar: Delimitation CommissionSoubhik MukherjeeNo ratings yet