Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Case of Phobic Anxiety Related To The Inability To Smell Cyanide

Uploaded by

Aris Dwi RahimOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Case of Phobic Anxiety Related To The Inability To Smell Cyanide

Uploaded by

Aris Dwi RahimCopyright:

Available Formats

Occup Med.

1994; 44: 107-108

A case of phobic anxiety

related to the inability to smell

cyanide

P. J. Nicholson* and G. E. P. Vincentif

*ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd, Billingham, Cleveland and

^Department of Mental Health, Friar age Hospital, Northallerton,

North Yorkshire, UK

BACKGROUND

Cyanide is well known for its properties as one of the

most rapidly acting lethal poisons - inhalation of high

cyanide gas concentrations produces symptoms within

seconds. Hydrolysis of cyanide salts by atmospheric

water vapour causes the slow release of hydrogen

cyanide, the odour of which is described as bitter

almonds by those who can smell it. Some individuals

can only detect hydrogen cyanide either as an unpleasant

metallic taste or as a vague sensation in the mouth or

nasal passages; while other individuals are unable to

detect hydrogen cyanide by odour.

Laboratory studies have demonstrated a sex difference

in the ability to smell hydrogen cyanide when subjects

are presented with a solution of 20 per cent potassium

cyanide (Table / ) . It has been suggested that the ability

to smell cyanide is a sex-linked recessive phenomenon1

with multiple allelism or genetic modifiers2*3. Sayek3

and Brown and Robinette4 have also demonstrated three

groups of 'smellers', ie good smellers, weak smellers

and non-smellers. However, in the latter study, no

consistent or significant sex difference was observed.

Studies on the ability to smell hydrogen cyanide are

based on different methodologies, which makes exact

comparison between studies difficult; however, a sex

difference appears to be more demonstrable in adults

than in children.

A report of an acute exposure incident at an industrial

plant lends support to laboratory studies which show

that some individuals cannot detect the odour of

hydrogen cyanide. Peden et al? described nine men

who developed symptoms as a result of absorption of

appreciable amounts of hydrogen cyanide, as shown by

blood analysis, when none of the men had definitely

identified hydrogen cyanide by smell.

Personal alarm monitors are available to detect

cyanide; however, the ability to smell hydrogen cyanide

at low concentrations remains an important method of

detecting low-grade accidental releases. The odour

threshold for hydrogen cyanide is between 0.2 and 5.0

parts per million6, below the occupational exposure

limit or threshold limit value of 10 parts per million, and

well below concentrations that would produce acute

symptoms. A 'sniff test' is available for recognition

training, and it is possible to train some individuals to

smell cyanide by allowing them to sniff from a test bottle

containing potassium cyanide solution every day for

several days.

CASE REPORT

Mr X was a 29-year-old process operator who had

worked for 18 months in the cyanide production area

of a large chemical plant. His manager suspected that

he was developing a phobia in relation to cyanide,

because it was known that Mr X could not smell cyanide

despite attempts at training and because he had

generated three false 'HCN alarms'. He was referred

to the occupational health department, and it was noted

from his health records that he had attended the

department four months earlier as a case of suspected

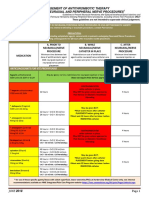

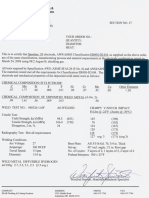

Table 1. Incidence of inability to smell a 20 per cent solution of

potassium cyanide

Incidence of

inability

Population

White Australians

Japanese

Correspondence and reprint requests to: P. J. Nicholson, Procter &

Gamble Ltd, PO Box 1EE, Qosfortti, Newcastle upon Tyne NE99 1EE,

UK.

1994 Butterworth-Helnemann for SOM

0962-7480/94/020107-02

Turks

Sex

Reference

M

F

M

F

M

F

24/132

5/112

39/214

12/219

9/68

2/98

18.2

4.5

18.2

5.5

13.2

2.0

1

2

3

Downloaded from http://occmed.oxfordjournals.org/ at Harvard University on April 15, 2015

This report describes a case of phobic anxiety relating to cyanide in a process

operator who is unable to smell hydrogen cyanide. This case demonstrates that

hazardous substances in the workplace can provoke this mental disorder in

individuals who are unable to detect by special senses whether or not a specific

hazard is present. The clinical management of such individuals is complicated since

they must be able to perceive the feared object or substance in order to overcome

their anxiety.

108

Occup. Med. 1994, Vol 44, No 2

DISCUSSION

The clinical diagnosis was phobic anxiety (ICD9 code

300.2) focused on the cyanide facility at Mr X's place

of work. There was no evidence of depression or

free-floating anxiety. The death of Mr X's friend

impressed on him a sense of personal vulnerability, and

the unfortunate death of his brother-in-law came in the

midst of an anniversary reaction at a time when Mr X

was trying to adjust to the new challenge of the hydrogen

cyanide plant.

Mr X is unable to smell cyanide, and only felt safe

in the plant if accompanied by a colleague. Mr X is not

generally an anxious individual, and his pre-morbid

personality would seem to have been stable.

Phobic disorders have an overall prevalence of 6 per

cent, with agoraphobia and social phobia being the most

common7. Simple or specific phobias can occur in

response to single traumatic events, or they can arise

at a time of background stress and concern8, as perhaps

happened in this case. Once established, phobias tend

to persist, as predicted from learning theory.

There are two ways in which an individual can deal

with phobic anxiety. One is to avoid the fear-provoking

situation altogether. Alternatively, desensitization through

gradually increasing exposure to the feared stimulus is

employed, and forms the cornerstone of treatment9.

Additionally, anxiety management and cognitive therapy

can enhance treatment efficacy10. Drug treatment has

its advocates11>12, but it is generally agreed that exposure

treatment forms the basis for a successful outcome13.

In Mr X's case, it seemed unlikely that desensitization

would be successful. Increasing his exposure at the plant

to solid and liquid forms of cyanide (which he could

perceive visually) would be unlikely to resolve his

problem because his phobic anxiety was specifically to

hydrogen cyanide gas and his inability to perceive its

presence by virtue of its odour. An individual must be

able, to perceive the specific feared object or substance

if he is to be able to accommodate it through exposure.

Therefore, it was recommended that Mr X be moved

to a different job within the plant.

REFERENCES

1. Kirk RL, Stenhouse NS. Ability to smell solutions of

potassium cyanide. Nature 1953; 171: 698-9.

2. Fukomoto Y, Nakajima H, Uetake M, Matsuyama A,

Yashida T. Smell ability to solutions of potassium cyanide

and its inheritance. Jpn J Hum Genet 1957; 2: 7-16.

3. Sayek I. The incidence of the inability to smell solutions

of potassium cyanide in the rural health centre of

Ortabcreket. Turk J Pediatr 1970; 12: 72-5.

4. Brown KS, Robinette RR. No simple pattern of

inheritance in ability to smell solutions of cyanide. Nature

1967; 215: 406-8.

5. Peden NR, Taha A, McForley E, Bryden GT, Murdoch

IB, Anderson JM. Industrial exposure to hydrogen cyanide:

implications for treatment. Br Med J 1986; 293: 538.

6. Ellenhorn MJ, Barceloux DG. Medical Toxicology.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Poisoning. New York:

Elsevier, 1988.

7. Swinson RP. Phobic disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry

1992; 5: 238-^4.

8. Hawton K, Salkovskis P, Kirk J, Clark D (eds). Cognitive

behaviour therapy for psychiatric

problems.

Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1989.

9. Marks IM. Fears, phobias and rituals. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1987.

10. Michelson L, Ascher M (eds). Anxiety and stress

disorders: cognitive-behavioural assessment and treatment.

New York: Guildford Press, 1986.

11. Munjack DJ, Bruns J, Baltazar PL et al. A pilot study of

buspirone in the treatment of social phobia. J Anxiety

Disord 1991; 5: 87-98.

12. Reiter SR, Pollack MH, Rosenbaum JF, Cohen LS

Clonazepam for the treatment of social phobia. J Clin

Psychiatry 1990; 51: 470-2.

13. Gelder M, Gath D, Mayou R. Oxford Textbook of

Psychiatry (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications,

1989.

Downloaded from http://occmed.oxfordjournals.org/ at Harvard University on April 15, 2015

cyanide poisoning. On this occasion, Mr X had been

drawing samples from an effluent tank for laboratory

analysis. He felt dizzy on return to his place of work,

and he assumed that he had been exposed to hydrogen

cyanide gas. Qualitative analysis of a venous blood

sample was negative for cyanide and he returned to

work.

At interview in the occupational health department,

Mr X reported feeling anxious and aroused whenever

he was in the vicinity of hydrogen cyanide at work. He

described a feeling of panic that would last between 10

and 90 minutes, during which he felt dizzy and weak.

He also reported muscle tension, occipital headache,

blurred vision, shortness of breath and marked sweating.

These attacks only ever started at work, and their

frequency and intensity had increased over a period of

four to six months, so that even attending safety lectures

on cyanide made him uncomfortably agitated. It was

decided to refer Mr X for psychiatric opinion.

There was no family history of mental disorder, and

no formal history of previous psychiatric contact.

Mr X reported that his marriage was stable and he had

no pressing psychosocial concerns. However, two years

earlier, while on holiday, he learnt that a close friend

had been killed in an accident at the plant and the news

upset him greatly. A year later to the day, his

brother-in-law died unexpectedly from a myocardial

infarction, and at the same time Mr X was transferred

to the hydrogen cyanide plant.

Mr X presented as a fit-looking young man. His mood

was stable and calm at interview. There were no

psychotic phenomena and he denied any biological

symptoms of depression. He seemed to be of average

intelligence. He maintained that he could not smell

cyanide. He had experienced no problems either in

training or working with liquid cyanide, but he admitted

that his inability to smell cyanide worried him greatly.

In his previous jobs, he had become used to working

with more obviously pungent chemicals such as urea

and chlorine, and so had felt no sense of personal danger.

You might also like

- 2006 2 SMRI - Research Report PartIDocument131 pages2006 2 SMRI - Research Report PartIActionman2100% (1)

- The New Oxygen Prescription: The Miracle of Oxidative TherapiesFrom EverandThe New Oxygen Prescription: The Miracle of Oxidative TherapiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (16)

- Hydrogen Medicine: Combining Oxygen, Hydrogen, and Co2From EverandHydrogen Medicine: Combining Oxygen, Hydrogen, and Co2Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Stop Anticoagulation Neuraxial AnesthesiaDocument3 pagesStop Anticoagulation Neuraxial AnesthesiaGihan NakhlehNo ratings yet

- Oxidation and Reduction Reactions in Organic ChemistryDocument9 pagesOxidation and Reduction Reactions in Organic ChemistryTarun Lfc Gerrard100% (1)

- Research ArticleDocument5 pagesResearch ArticleStefhani GistaNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument6 pagesResearch ArticleqsdfqsdfNo ratings yet

- Kaala Pathar Paraphenylene Diamine Poisoning and Angioedema in A Childan Unusual Encounter 2161 0495 1000294Document3 pagesKaala Pathar Paraphenylene Diamine Poisoning and Angioedema in A Childan Unusual Encounter 2161 0495 1000294Tabish JavaidNo ratings yet

- Quiz 2 Alternative ToxicologyDocument8 pagesQuiz 2 Alternative Toxicologyfarhanyasser34No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Depression in The Acute Phase of First Episode SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Clinical Correlates of Depression in The Acute Phase of First Episode SchizophreniaahmadNo ratings yet

- Health Effects or Tear Gas Exposure in ChildrenDocument2 pagesHealth Effects or Tear Gas Exposure in ChildrenAlberto GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Mnagement Cyanide Smoke InhalationDocument10 pagesMnagement Cyanide Smoke InhalationMerlin PakayaNo ratings yet

- A Case of Antibiotic Associated Mania in A 67 Years Old WomanDocument6 pagesA Case of Antibiotic Associated Mania in A 67 Years Old WomananaNo ratings yet

- "'Bath Salts" Intoxication: A New Recreational Drug That Presents With A Familiar ToxidromeDocument7 pages"'Bath Salts" Intoxication: A New Recreational Drug That Presents With A Familiar ToxidromeEliana TorresNo ratings yet

- Articulo de Intoxacion Por CianuroDocument9 pagesArticulo de Intoxacion Por CianuroAdriana Torres PachecoNo ratings yet

- Fire Research Identified 57 Toxins With Polystyrene CombustionDocument7 pagesFire Research Identified 57 Toxins With Polystyrene CombustionbubisharbiNo ratings yet

- Nad Therapy Too Good To Be True Theo Verwey Abram Hoffer Ebook PDFDocument150 pagesNad Therapy Too Good To Be True Theo Verwey Abram Hoffer Ebook PDFpdf ebook free download100% (1)

- The Art of Healing PDFDocument5 pagesThe Art of Healing PDFT.BieniekNo ratings yet

- Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease Presenting After Consumption of Miracle Mineral Solution' (Sodium Chlorite)Document3 pagesKikuchi-Fujimoto Disease Presenting After Consumption of Miracle Mineral Solution' (Sodium Chlorite)Miriam CruzNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Organophosphorus PoisoningDocument6 pagesThesis On Organophosphorus Poisoningafcmtjcqe100% (2)

- Hygenics - 複本Document86 pagesHygenics - 複本Wai Kwong ChiuNo ratings yet

- PraktikumDocument28 pagesPraktikumMirna auliaNo ratings yet

- Jur DingDocument4 pagesJur DingerwinNo ratings yet

- Chiong - Toxicology Lab FinalDocument5 pagesChiong - Toxicology Lab FinalJohn Miguel ChiongNo ratings yet

- SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesSchizophreniaGabriela ValdiviaNo ratings yet

- 2007, Vol.25, Issues 1, Photodynamic TherapyDocument114 pages2007, Vol.25, Issues 1, Photodynamic TherapyRizweta DestinNo ratings yet

- AnnMovDisord2239-5235143 143231Document9 pagesAnnMovDisord2239-5235143 143231Raul de Sousa RamosNo ratings yet

- PhChem 421 ManualDocument70 pagesPhChem 421 ManualSomethingSomething SomethingNo ratings yet

- Suicidal Attempt by Disinfectant Solution IngestionDocument4 pagesSuicidal Attempt by Disinfectant Solution IngestionDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Michael Schaer-Clinical Signs in Small Animal Medicine-Manson Pub. - The Veterinary Press (2008) PDFDocument289 pagesMichael Schaer-Clinical Signs in Small Animal Medicine-Manson Pub. - The Veterinary Press (2008) PDFRodrigo Lazzarotto100% (2)

- Michael Schaer-Clinical Signs in Small Animal Medicine-Manson Pub. - The Veterinary Press (2008) PDFDocument289 pagesMichael Schaer-Clinical Signs in Small Animal Medicine-Manson Pub. - The Veterinary Press (2008) PDFRodrigo Lazzarotto100% (1)

- Treatment of Chancroid With Enoxacin: ReferencesDocument3 pagesTreatment of Chancroid With Enoxacin: References7dsp7xvs8dNo ratings yet

- Chemosensory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Prevalences, Recovery Rates, and Clinical Associations On A Large Brazilian SampleDocument7 pagesChemosensory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Prevalences, Recovery Rates, and Clinical Associations On A Large Brazilian SampleFernanda Santos de AssisNo ratings yet

- Accidental Carbon Monoxide Poisoning With Neurological SequelaeDocument3 pagesAccidental Carbon Monoxide Poisoning With Neurological SequelaeAtiquzzaman RinkuNo ratings yet

- Factor Affecting Poisoning: Submitted To: Dr. Muhammad Fawad Rasool Submitted byDocument18 pagesFactor Affecting Poisoning: Submitted To: Dr. Muhammad Fawad Rasool Submitted byXtylish RajpootNo ratings yet

- Seborrheic Dermatitis Treatment With Mustard Oil: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesSeborrheic Dermatitis Treatment With Mustard Oil: A Case ReportSrinivasulu BandariNo ratings yet

- Coral KeratitisDocument16 pagesCoral KeratitisloretoNo ratings yet

- BacteriologyDocument10 pagesBacteriologyGia UrdaiaNo ratings yet

- Study of Different Treatment Modalities and Outcome in Preterm Babies With Respiratory Distress Syndrome 2017Document4 pagesStudy of Different Treatment Modalities and Outcome in Preterm Babies With Respiratory Distress Syndrome 2017Vita DesriantiNo ratings yet

- AntipsychoticsDocument5 pagesAntipsychoticsapi-639751111No ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Care of Chloroquine Phosphate in Elderly Patients With Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19)Document4 pagesPharmaceutical Care of Chloroquine Phosphate in Elderly Patients With Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19)Elefteria KoseoglouNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Case PresentationDocument20 pagesUnit 1 Case PresentationPrabha Amandari Sutyandi0% (1)

- Clinical Cases in PsychiatryDocument161 pagesClinical Cases in PsychiatryAna Roman100% (35)

- Zidovudine in HIVDocument1 pageZidovudine in HIVAyu Ersya WindiraNo ratings yet

- Nicotine From Edible Solanaceae and Risk of Parkinson Disease (ANA-12-1625)Document9 pagesNicotine From Edible Solanaceae and Risk of Parkinson Disease (ANA-12-1625)Jahuey UnalescoNo ratings yet

- Advancements in The Study of H2S Toxicology. IIDocument13 pagesAdvancements in The Study of H2S Toxicology. IIMurthy FSAINo ratings yet

- HalitosisDocument6 pagesHalitosispratyusha vallamNo ratings yet

- Fatal Suicidal Case of Cyanide Poisoning A Case Report O6IgDocument2 pagesFatal Suicidal Case of Cyanide Poisoning A Case Report O6IgRéka StrîmbuNo ratings yet

- Xiaolong Wang PHD Emergency Department The 2 Affiliated Hospital of CqmuDocument51 pagesXiaolong Wang PHD Emergency Department The 2 Affiliated Hospital of CqmuNidya PutrijNo ratings yet

- Left Temporal Lobe Arachnoid Cyst Presenting With Symptoms of PsychosisDocument4 pagesLeft Temporal Lobe Arachnoid Cyst Presenting With Symptoms of PsychosisJAVED ATHER SIDDIQUINo ratings yet

- BMJ Case ReportDocument4 pagesBMJ Case ReportGisda AzzahraNo ratings yet

- Acut44 LithiumDocument6 pagesAcut44 LithiumAncaNo ratings yet

- Homeopathy DissertationDocument8 pagesHomeopathy DissertationWhereToBuyPapersSingapore100% (1)

- 307 FullDocument4 pages307 Fullpjmk MatraNo ratings yet

- Metaanális de Los Factores de Riesgo en La Enfermedad de ParkinsonDocument8 pagesMetaanális de Los Factores de Riesgo en La Enfermedad de ParkinsonAlejandraTiradoNo ratings yet

- Preclinical PsychopharmacologyFrom EverandPreclinical PsychopharmacologyD.G. Grahame-SmithNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Psychosis in Parkinson's Disease: Finding the right therapeutic balanceFrom EverandFast Facts: Psychosis in Parkinson's Disease: Finding the right therapeutic balanceNo ratings yet

- Why Am I Sick?: Eliminate the Causes and Be Well Forever!From EverandWhy Am I Sick?: Eliminate the Causes and Be Well Forever!No ratings yet

- Fluoroquinolone-Associated Disability (FQAD) - Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, Therapy and Diagnostic Criteria: Side-effects of FluoroquinolonesFrom EverandFluoroquinolone-Associated Disability (FQAD) - Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, Therapy and Diagnostic Criteria: Side-effects of FluoroquinolonesNo ratings yet

- Disease Reprieve: Living into the Golden YearsFrom EverandDisease Reprieve: Living into the Golden YearsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Parkinson’s Disease Therapeutics: Emphasis on Nanotechnological AdvancesFrom EverandParkinson’s Disease Therapeutics: Emphasis on Nanotechnological AdvancesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Studies and Therapies in Parkinson's Disease: Translations from Preclinical ModelsFrom EverandClinical Studies and Therapies in Parkinson's Disease: Translations from Preclinical ModelsNo ratings yet

- E Grout Mc050Document2 pagesE Grout Mc050Tori SmallNo ratings yet

- MetalCoat 470 480 Brochure enDocument9 pagesMetalCoat 470 480 Brochure endanceNo ratings yet

- 1 1Document9 pages1 1Ankush SehgalNo ratings yet

- List Drug Food InteractionsDocument8 pagesList Drug Food InteractionsAliza Raudatin SahlyNo ratings yet

- FDA-356h 508 (6.14)Document3 pagesFDA-356h 508 (6.14)sailaja_493968487No ratings yet

- PAMG-PA3 5052 Aluminum Honeycomb: DescriptionDocument2 pagesPAMG-PA3 5052 Aluminum Honeycomb: Descriptionsahiljain_146No ratings yet

- Chemical Basis of LifeDocument5 pagesChemical Basis of LifeCaithlyn KirthleyNo ratings yet

- Abilify Maintena Epar Public Assessment Report enDocument70 pagesAbilify Maintena Epar Public Assessment Report enWara RizkyNo ratings yet

- Pioglitazone NaopaticlesDocument11 pagesPioglitazone NaopaticlesAtiq Ur-RahmanNo ratings yet

- Titanium WeldingDocument16 pagesTitanium WeldingMuhammad IrdhamNo ratings yet

- AsdDocument3 pagesAsdMuStafaAbbasNo ratings yet

- 0653 - w12 - QP - 11 (Combined)Document20 pages0653 - w12 - QP - 11 (Combined)MCHNo ratings yet

- TDS OF H-408 Silicone Adjuvant For AgricultureDocument2 pagesTDS OF H-408 Silicone Adjuvant For AgricultureAda FuNo ratings yet

- Insulation System ClassDocument2 pagesInsulation System ClassVictor Hutahaean100% (1)

- ESAB Welding & Cu Ing Products: A515 516 4 In. Thick 2 In. Root GapDocument1 pageESAB Welding & Cu Ing Products: A515 516 4 In. Thick 2 In. Root Gapalok987No ratings yet

- LET FOODS Review MaterialsDocument10 pagesLET FOODS Review MaterialsNix RobertsNo ratings yet

- Rev004Document3 pagesRev004Issam LahlouNo ratings yet

- Nitobond SBR PDFDocument4 pagesNitobond SBR PDFhelloitskalaiNo ratings yet

- Praktikum Biofarmasetika: Data Penetrasi TransdermalDocument6 pagesPraktikum Biofarmasetika: Data Penetrasi TransdermalCindy Riana Putri FebrianiNo ratings yet

- Basf Masterflow 649 TdsDocument4 pagesBasf Masterflow 649 Tdsgazwang478No ratings yet

- Ajax Disinfectant CleanserDocument11 pagesAjax Disinfectant CleanserMateusPauloNo ratings yet

- Petroleum Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesPetroleum Dissertation TopicsEnglishPaperHelpCanada100% (1)

- Dissolution GelatinDocument14 pagesDissolution Gelatinايناس ماجدNo ratings yet

- Reading Focus Grade 7Document38 pagesReading Focus Grade 7Khristie Lyn AngNo ratings yet

- Solutios, Solutions of Non Electrolyte - 2019-2020 v2Document80 pagesSolutios, Solutions of Non Electrolyte - 2019-2020 v2hazo hazNo ratings yet

- Lab 15 - Effects of Catalyst On Reaction RateDocument2 pagesLab 15 - Effects of Catalyst On Reaction Ratealextzhao1996No ratings yet

- Siltech E50Document4 pagesSiltech E50Rajesh ChowdhuryNo ratings yet