Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Too Much Duty

Uploaded by

gregm0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views1 pageFlightSafetyAustralia 97

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFlightSafetyAustralia 97

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views1 pageToo Much Duty

Uploaded by

gregmFlightSafetyAustralia 97

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

A

few years ago, I took the jump seat on

a regular public transport flight from

Chicago to Phoenix on one of those

"red eye" specials. I had been up 36 hours trying to get home to Tucson.

It was the captain's leg and he was settling

back to read the paper. The first officer

seemed pretty relaxed, with his arm propped

on the glare shield looking out on the horizon. I didn't notice anything peculiar about

the scene so I tried to get some sleep.

Finally, ATC gave us a call to switch to Albuquerque Center, but no one stirred. The second call came a few minutes later, but still no

one moved.

As if on cue, another call came piping

through. The captain, now fully alert,

wrapped up his newspaper and hit the first

officer, "Hey wake up - Center is trying to get

you on the radio!"

We all seem to struggle in these conditions

of fatigue and overwork. Often it is for the

love of flying - but more commonly to get on

with our careers.

I remember during one interview, a member of the panel asked: "Have you ever broken any rules in your aviation career?" I

answered that I was fortunate enough to have

been employed by carriers that had never

asked me to break any rules for their benefit.

I left ashamed for "bending" the truth - but

I wanted the job. Although the company never

asked me to exceed duty times, it was clearly

the norm to work all day in the office, fly a few

hours, and then log only the forty-five minutes

before and fifteen minutes after the flight in

duty time records. After all, the company knew

I wanted to log flight time and I was no use if

I had exceeded my duty time limitations.

The end result was extreme fatigue, caused

by long days, several sectors, sometimes over

25 landings in a day, aircraft vibration and,

on occasion, IFR flights down to the minima.

The easiest time to omit is the time spent in

the office - no flight plans, fuel dockets or

AVDATA details to catch you out.

As a line pilot in general aviation, I felt it

my duty to "help" the company out by omission of duty times. I soon found myself working seven days straight, 120 hours duty per

fortnight and logging 29.9 hours per week.

Although I only flew six of the seven days,

my day of rest was spent either in the office

or washing planes. Soon, I hated my job.

But the reality of the danger did not occur

to me until a day after completion of a fourweek tour of duty with three days off in

between. Driving through the city, I was so

tired that I stopped caring about staying in my

lane. I laughed, and thought, "I just don't care'

I suddenly recognised that the same attitude had crept into my flying. So I vowed to

12 FLIGHT SAFETY AUSTRALIA AUTUMN 1997

Red-eye

special

How one pilot learned to say

no to excess duty times - and

got a promotion.

Although the pilots complained that their

flying hours decreased, after a while they

realised the benefits of some leisure time, and

began to appreciate the company as well.

For the first time, we stopped losing pilots

to other companies. We got more applications

from highly skilled pilots. Our training budget for the next financial year was underspent

because the new, highly skilled pilots required

less training. And they stayed longer.

Pilots are not doing a company any service

by more than 90 hours a fortnight at the airport.

Although I do not feel the laws in Australia

on flight and duty times are well written, they

can be made to work - with some difficulty to a charter operator's schedule. It takes effort

from both sides of the line.

UBTLE AND

direct presSsures

to

company as much as

possible to achieve operational goals can

mean accepting a lower salary or violating

minima.

The result is a level of pressure on the pilot

which can compound the symptoms of

fatigue. There is no doubt that this leads to

below optimal operational standards.

This is a hard situation to face. How easy is

it to say "no"? And should the pilot have to

say no? The pilot is in a vulnerable situation,

and it is the manager who holds all the cards.

General aviation depends upon a professional approach to aviation and flight safety.

Perhaps managers need to develop a greater

understanding of fatigue and stress.

It is not uncommon for pilots to fall asleep

during long-haul operations in advanced technology aircraft. There are a number of opinions as to why this occurs, such as a pilot's "body

clock" being out of sync due to irregular hours.

However, the most obvious factor relates to

boredom or "underload'

The symptoms of fatigue include a shorttempered attitude, focusing attention on a

single task, lack of concentration, irritability,

degradation in operational performance, and

- of course - sleepiness.

When you are fatigued, you often don't

know it. You might try to force yourself to perform.

In some cases, this results in missed information and errors which can contribute to an

accident. This situation cannot be regulated.

It is a decision which remains, and will probably always remain, with the pilot.

ANkY, IS

keep close to duty times, and to relax. I soon

found myself enjoying the job again.

After a while, I was promoted to management, because I had learned the diplomatic art

of saying no. My health, attitude and productivity improved. I tried subtly to get other pilots

in the company to follow my example. But they

would have nothing to do with it - the flight

hours were still the dangling carrot.

Everyone was "happy" because they were

getting the all important hours to get into a

regional. Aviation was more than a job - it

was life itself. After a few months, the other

pilots found themselves in the same predicament I had gone through.

The director could not understand why people

were getting upset. Morale hit rock bottom,

with rumblings of pay disputes. Something had

to give. We added more pilots and ground staff

to combat the problem of exploitation of

pilots and the resultant fatigue.

It was a hard decision at first, but was necessary for the long term. We had good

employees who knew our operation. Management understood that attrition of skilled

labour cost the company in the long term.

Mark Wiggins, department of aviation studies.

University of Western Sydney, Macarthur.

You might also like

- Plan and assess maintenance programs for class B aircraftDocument1 pagePlan and assess maintenance programs for class B aircraftgregmNo ratings yet

- CPL Human FactorsDocument8 pagesCPL Human FactorsgregmNo ratings yet

- Wind Farm Development and AerodromesDocument4 pagesWind Farm Development and AerodromesgregmNo ratings yet

- Stabilised ROD For ApproachesDocument1 pageStabilised ROD For ApproachesgregmNo ratings yet

- Mountain WavesDocument2 pagesMountain WavesgregmNo ratings yet

- De VinedDocument2 pagesDe VinedgregmNo ratings yet

- Shadin 91053 Operation ManualDocument36 pagesShadin 91053 Operation Manualmglem100% (1)

- How To Survive Engine FailuresDocument1 pageHow To Survive Engine FailuresgregmNo ratings yet

- GPS NpaDocument3 pagesGPS Npagregm100% (1)

- Book ReviewDocument1 pageBook ReviewgregmNo ratings yet

- AdvancedDocument5 pagesAdvancedgregmNo ratings yet

- Global Air TrafficDocument1 pageGlobal Air TrafficgregmNo ratings yet

- QuizDocument8 pagesQuizgregmNo ratings yet

- Excess BaggageDocument1 pageExcess BaggagegregmNo ratings yet

- A Crack in The LineDocument1 pageA Crack in The LinegregmNo ratings yet

- A Crack in The LineDocument1 pageA Crack in The LinegregmNo ratings yet

- Air WorthinessDocument2 pagesAir WorthinessgregmNo ratings yet

- Fabric bonding failureDocument1 pageFabric bonding failuregregmNo ratings yet

- Communications BreakdownDocument4 pagesCommunications BreakdowngregmNo ratings yet

- AerobaticsDocument1 pageAerobaticsgregmNo ratings yet

- Noise DamageDocument3 pagesNoise DamagegregmNo ratings yet

- Rats in The M: - QqocoaoDocument2 pagesRats in The M: - QqocoaogregmNo ratings yet

- Guide to Operations Manual PreparationDocument67 pagesGuide to Operations Manual PreparationgregmNo ratings yet

- DR NavigationDocument6 pagesDR NavigationgregmNo ratings yet

- Visual NavigationDocument31 pagesVisual Navigationgregm100% (1)

- Multi-Engine Safety Review Course NotesDocument14 pagesMulti-Engine Safety Review Course NotesgregmNo ratings yet

- 25 Tips To Be A Better PilotDocument5 pages25 Tips To Be A Better PilotgregmNo ratings yet

- Navigation QuestionsDocument5 pagesNavigation Questionsgregm100% (1)

- Radio Navigation QuestionsDocument11 pagesRadio Navigation Questionsgregm100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pyrometallurgical Refining of Copper in An Anode Furnace: January 2005Document13 pagesPyrometallurgical Refining of Copper in An Anode Furnace: January 2005maxi roaNo ratings yet

- Chill - Lease NotesDocument19 pagesChill - Lease Notesbellinabarrow100% (4)

- TEST BANK: Daft, Richard L. Management, 11th Ed. 2014 Chapter 16 Motivating EmplDocument37 pagesTEST BANK: Daft, Richard L. Management, 11th Ed. 2014 Chapter 16 Motivating Emplpolkadots939100% (1)

- Bernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsDocument3 pagesBernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsJean Marie DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Victor's Letter Identity V Wiki FandomDocument1 pageVictor's Letter Identity V Wiki FandomvickyNo ratings yet

- Emperger's pioneering composite columnsDocument11 pagesEmperger's pioneering composite columnsDishant PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Mapping Groundwater Recharge Potential Using GIS-Based Evidential Belief Function ModelDocument31 pagesMapping Groundwater Recharge Potential Using GIS-Based Evidential Belief Function Modeljorge “the jordovo” davidNo ratings yet

- ADSLADSLADSLDocument83 pagesADSLADSLADSLKrishnan Unni GNo ratings yet

- Proposal Semister ProjectDocument7 pagesProposal Semister ProjectMuket AgmasNo ratings yet

- BS EN 364-1993 (Testing Methods For Protective Equipment AgaiDocument21 pagesBS EN 364-1993 (Testing Methods For Protective Equipment AgaiSakib AyubNo ratings yet

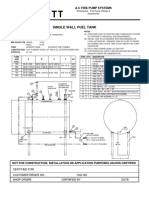

- Single Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump SystemsDocument1 pageSingle Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump Systemsricardo cardosoNo ratings yet

- Rencana Pembelajaran Semester Sistem Navigasi ElektronikDocument16 pagesRencana Pembelajaran Semester Sistem Navigasi ElektronikLastri AniNo ratings yet

- Keya PandeyDocument15 pagesKeya Pandeykeya pandeyNo ratings yet

- Ebook The Managers Guide To Effective Feedback by ImpraiseDocument30 pagesEbook The Managers Guide To Effective Feedback by ImpraiseDebarkaChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Ieee Research Papers On Software Testing PDFDocument5 pagesIeee Research Papers On Software Testing PDFfvgjcq6a100% (1)

- People vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Document1 pagePeople vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Grace GomezNo ratings yet

- John GokongweiDocument14 pagesJohn GokongweiBela CraigNo ratings yet

- Department Order No 05-92Document3 pagesDepartment Order No 05-92NinaNo ratings yet

- CCS PDFDocument2 pagesCCS PDFАндрей НадточийNo ratings yet

- Tata Group's Global Expansion and Business StrategiesDocument23 pagesTata Group's Global Expansion and Business Strategiesvgl tamizhNo ratings yet

- CAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000Document47 pagesCAP Regulation 20-1 - 05/29/2000CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Week 3 SEED in Role ActivityDocument2 pagesWeek 3 SEED in Role ActivityPrince DenhaagNo ratings yet

- 3838 Chandra Dev Gurung BSBADM502 Assessment 2 ProjectDocument13 pages3838 Chandra Dev Gurung BSBADM502 Assessment 2 Projectxadow sahNo ratings yet

- ASCE - Art Competition RulesDocument3 pagesASCE - Art Competition Rulesswarup babalsureNo ratings yet

- WELDING EQUIPMENT CALIBRATION STATUSDocument4 pagesWELDING EQUIPMENT CALIBRATION STATUSAMIT SHAHNo ratings yet

- Gates em Ingles 2010Document76 pagesGates em Ingles 2010felipeintegraNo ratings yet

- Pig PDFDocument74 pagesPig PDFNasron NasirNo ratings yet

- Conversion of Units of Temperature - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument7 pagesConversion of Units of Temperature - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFrizal123No ratings yet

- DSA NotesDocument87 pagesDSA NotesAtefrachew SeyfuNo ratings yet

- Bentone 30 Msds (Eu-Be)Document6 pagesBentone 30 Msds (Eu-Be)Amir Ososs0% (1)