Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alyattes' Median War

Uploaded by

Mohammad JamaliCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alyattes' Median War

Uploaded by

Mohammad JamaliCopyright:

Available Formats

Alyattes' Median War

Author(s): H. M. T. Cobbe

Source: Hermathena, No. 105 (Autumn 1967), pp. 21-33

Published by: Trinity College Dublin

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23039968

Accessed: 26-05-2016 23:37 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Trinity College Dublin is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hermathena

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median War

by

H. M. T. Cobbe*

I

The war between Alyattes and Media has recently been discussed

in the light of a fragment from Oxyrhynchus published in 1963.1

The problem presented by the fragment is that it seems to mention

a war between Alyattes and, not Cyaxares, as in Herodotus, but

Astyages, implying that either there was a separate war between

Lydia and Media not mentioned in Herodotus or else Astyages took

over command, either as king or as general in place of Cyaxares,

before the war was finished. I propose to show (1) that there was

stronger evidence for such a tradition extant before the papyrus was

discovered than has so far been pointed out; (2) to construct a

coherent outline of events, independent of Herodotus, that may well

have been known to the author of the fragment; (3) to examine the

implications of this account.

There are two interesting passages in Roman literature concerned

with an eclipse, which is said to have been foretold by Thales, in

May 585 B.C.:2

(1) Cicero, De divinatione 1.49/112: ' Et quidem idem (sc.

Thales) defectionem solis, quae Astyage regnante facta est, praedixisse

fertur.'

(2) Pliny, Naturalis historia 2.53: ' Apud Graecos autem invest

igavit primus omnium Thales Milesius Olympiadis XLVIII anno

quarto, praedicto solis defectu qui Alyatte regnante factus est Urbis

conditae anno CLXX.'

One striking similarity between the two passages is that in both

cases the eclipse is associated with a reigning king despite the fact

that Thales, the central figure in both passages, is not known to be

associated with either of the two kings mentioned. In the accounts

that Cicero and Pliny knew, the eclipse was associated with both

Astyages and Alyattesthis is clear if one puts the two passages

* The notes begin on p. 31.

21

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

togetherbut neither author says why these two kings in particular

should have been associated with it. However a passage of Solinus

relates the two rulers:

(3) Solinus, 15.16: ' Scythae . . . haustu mutui sanguinis foedus

sanciunt non suo tantum more sed Medorum quoque usurpata

disciplina. Bello denique quod gestum est Olympiade nona et quadra

gesima, anno post Ilium captum sexcentesimo quarto, inter Alyatten

Lydum et Astyagen Mediae regem, hoc pacto firmata sunt iura pads.'

So here we have a connexion between Alyattes and Astyages, with

no mention of the eclipse at all. The three passages, when taken

together, form a coherent tradition thus: There was a war between

Alyattes and Astyages, and an eclipse occurred which had been

foretold by Thales; somehow this eclipse was connected with the

war. We can go further than this by examining the dates given by

Pliny and Solinus. Pliny dates the eclipse to OI.48.4, i.e. to 585/4 B.C.

(He is slightly out, however, since May 585 B.C. falls in the Olympic

year 586/5 B.C.OI.48.3but this does not affect the argument

at this stage.) Solinus dates what is presumably the end of the war

and the peace to OI.49 (584/3-581/0), fixing the actual year within

the Olympiad by stating that it was the 604th year after the fall of

Troy. Now it so happens that one of the dates for the fall of Troy

that has come down to us fits in here very wellthe Apollodoran

1184/3 B.C. gives 582/1 B.C.3 Thus we are given a minimum of

three years' duration for the war, this being the interval between the

eclipseat which time the war must have been in progress, for

otherwise there would have been no reason for associating the eclipse

with the two kingsand the peace.4

This is about as far as we can go in reconstruction, using these

three passages alone; however Eusebius' Chronicle also mentions this

war, and can be related to what has been discussed. The entries in

this work that deal with the war, and the Olympic dates under which

they appear, are as follows in the two extant versions (St Jerome's

and the Armenian versionhereafter St J. and AV):

AV5

01.49.2:'Die Sonne ward verfinstert nach Thales des Weisen

Vorauskiindigung. Aliates und Azhadak lieferten eine Schlacht.'

OI.51.2: 'Azhadak lieferte gegen die Lyder einen heftigen

Kampf.'

22

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

St J.6

OI.48.3 : ' Solis facta defectio cum futuram earn Thales ante

dixisset.'

01.49.3 : ' Alyattes et Astyages dimicaverunt.'

01.50.4 : ' Astyages contra Lydos pugnat.'

Eusebius' original pattern, so far as the entries, but not the dates,

are concerned, is made clear by placing the two series of entries side

by side; and the resultant pattern is this :

(a) eclipse,

(1b) battle between Astyages and Alyattes,

(c) war waged by Astyages against the Lydians.

However the dates given by the two versions differ considerably, and

they may be expressed in terms of Christian years thus:

AV St J.

Eclipse 582/1 B.C. 586/5 B.C.

Battle 582/1 582/1

War 574/3 577/6

The remarkable point is that St Jerome's dates for the first two

entries correspond closely with the dates for the eclipse and the peace

in Pliny and Solinus respectively,8 and so would appear to come from

the same tradition; consequently we may take it that Eusebius' battle

between Astyages and Alyattesthe middle entry in the series out

lined abovewas the final engagement of the war and marks the

end of it.9 It is also remarkable that AV agrees with St J. in putting

the battle in the year 582/1 B.C., and we may assume that this was

the date given in Eusebius' original text. There is no principle

underlying the variations in the dates given by the two versions, apart

from that outlined in note 7, and so any point of agreement need

not be automatically suspect. The fact that AV puts both the eclipse

and the battle in the same year would naturally lead one to suppose

that Herodotus' eclipse battle is intended.10 However since St J. does

not associate the two events, it seems more likely that this later battle

in Eusebius has been confused with the eclipse battle in Herodotus by

the compiler of AV and that, as a result, the eclipse has been brought

down to the year of the battle to make them coincide.

So far then the Eusebian tradition can be reconciled with that of

Cicero, Pliny and Solinuswhich I shall hereafter call the CPS

tradition for convenience. However there is one entry in the Chronicle

that has so far been neglected, the last entry in both the A V and the

23

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

St J. series. This mentions an entirely different war which Astyages

waged against the Lydians and is worded in very much the same way

in both versions. Couched in more general terms than the preceding

entry, it definitely seems to imply a second war, begun by Astyages,

taking place after the one already considered. This second war is

dated 574/3 by AV and 577/6 by St /., but these divergent dates

can be reconciled: we have seen that we need have little hesitation

in lowering the St J. date for the eclipse by one year;11 thus the

interval between the eclipse year and the year of the second war

becomes eight years. Now in AV the interval is also eight years, and

so it is likely that in the original text of the Chronicle these two events

were placed eight years apart; it has already been suggested that the

eclipse has been lowered by three years to the same year as the battle

(582/1 B.C.) in AV because of confusion with the eclipse battle. As

a result of this, the lower limit of the period had to be lowered also

in order to preserve the eight year interval; therefore Eusebius' own

date for the second war was probably the one that now appears in

St J.

The preceding argument has, I hope, shown that we have the

outline of a tradition in Eusebius, for the earlier part of which there

is evidence in the CPS tradition also; in other words, that the earlier

three authors between them indicate a coherent tradition which also

appears to lie behind a series of entries in Eusebius; the Eusebian

series, however, goes further in such a way as to make it probable

that it is continuing the same tradition, although this cannot be

confirmed from elsewhere. This tradition, then, has a war in progress

between Astyages and Alyattes at the time of the ' Thales-eclipse',

in OI.48.4. There was a peace three years later, at which the oaths

were consecrated ' haustu mutui sanguinis', but five years after that

Astyages declared war on Lydia, and so the two powers fought once

again.

The origin of the CPS tradition is by no means enshrouded in

mystery. One of the prominent features of the passages in Pliny and

Solinus is that the two authors go out of their way to give a date for

the events they mention. Here, unlike the Eusebian passages where

the whole point of the entry is the date attached to it, the emphasis

lies not on the date but, in the one case, on the eclipse, which is the

topic that Pliny happens to be dealing with at the time, and, in the

other, on the fact that both the Scyths and the Medes consecrate their

oaths in the same way; so it would seem that the two dates were

included because they happened to be readily available in the source

24

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

that was being used; and, if so, this is a clear hint that this source

was a work of a chronographic nature, presumably hellenistic. The

fact that Eusebius has the same datesand his source cannot have

been anything other than chronographiclends strong support for

this hypothesis. The origin of the CPS tradition is probably to be

ascribed to Apollodorus since, firstly, Solinus synchronises the 604th

year after the fall of Troy with the 49th Olympiad, a combination

that only makes sense in terms of the Apollodoran 1184/3 B.C., as

has already been pointed out; secondly, there is another instance of

Solinus using an Apollodoran date in a Lydian contextfor the fall of

Sardis;12 and thirdly, Apollodorus dated the eclipse to the same year

as Pliny and St J.585 B.C.and used it as the on<nr| on which to

base his dates for Thales.13

Such then is the CP.S'-chronographic tradition dealing with

Alyattes' wars with Media, as it stood in Roman times, and, as has

been shown, it can be traced back at least as far as Apollodorus,

i.e. as far back as the mid-second century B.C.

II

Herodotus mentions the war in three places1.16.2, 1.74 and

1.103.2. In the first passage he simply says that Alyattes fought with

Cyaxares and the Medes, giving no more detail than that; the last

passage is equally brief:

ouros (sc. o Kuaapr|s) o xoTcrt Au8oia( ecrri (jaxecr&nsvos ots vu f]

f|(Jiepr| gyevETO crqn (iaxopivoicri kccI o tt]V "AAuos ttotcxijoO avco 'Acririv

Traaav avorrio-as iaurw.

This passage is a back reference to the second of the three passages

with which we are concerned, where the main account of the war

appears1.73.3 f-14 This main account is in fact introduced as a

parenthesis to explain why Croesus felt impelled to avenge Astyages,

rather than in its proper chronological place in 1.16. This displace

ment may be due to Herodotus' artistic arrangement of his work, or

else to an afterthought, a realisation that the war needed more detailed

treatment than he had supposed, because of its significance in relation

to Croesus' attitude to Cyrus.

The passage at 1.73.3 f- gives a cause for the war, a brief outline

of its course and some remarks on its conclusion. The cause of the

war was closely connected with a band of Scyths. Now there is very

likely to be more here than meets the eye, especially if one bears in

mind that (1) the Scythian invasion of the near East was originally

25

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

in pursuit of the Cimmerians,15 (2) Alyattes fought the Cimmerians

and expelled them from Asia Minor,16 and (3) the Scythians

dominated the Levant and Mesopotamia for a period until they were

expelled by the Medes." The first two points would imply at least a

common cause between Alyattes and the Scyths, and the last gives

very solid grounds for enmity between Cyaxares and the Scyths;

the three taken together indicate a slightly more plausible basis for

the war than that given by Herodotus, i.e. perhaps Alyattes aided

the Scyths when they were being expelled from Media, in return for

aid against the Cimmerians.

The points in Herodotus' account of the course of the war at

1.73.3 f- are 38 follows:

(1) It lasts for five years with neither side gaining the upper hand

in that time; (2) the eclipse battle occurred in the sixth year and this

made both sides eager for peace;18 (3) Syennesis the Cilician and

Labynetus the Babylonian acted as arbitrators19 and a marriage was

organised between Cyaxares' son, Astyages, and Aryene, the daughter

of Alyattes; (4) the oaths were consecrated in a similar manner to

that used by the Greeks, except that the participants mixed each

other's blood and drank it.

This account agrees with the CPS tradition on the following

points:

(1) The eclipse battle : although Cicero and Pliny do not mention

it, it is clear, when one compares the passages, that this battle must

lie behind their statements; it provides an excellent means of associ

ating Alyattes and the Median king with the eclipse. There is no

occasion for them to have mentioned the battle in the contexts of

their statements, which are purely concerned with the eclipse. (2) The

eclipse itself was said to have been predicted by Thalesthis is quite

clear from all the accounts we have. (3) The form in which the oaths

were consecrated appears also in the Solinus passage,20 and this can

mean either of two things : the form of taking the oaths was a feature

of the tradition that must eventually lie behind both Herodotus and

the chronographers, or else Solinus' source took the dates and the

name of the king from the chronographic tradition but such detail

as this from Herodotus.

Many of the other points in Herodotus' account can be reconciled

with the CPS traditioni.e. as being detail that may or may not

have been in the CPS tradition also. Examples of this are the

vuKTOiictxfa (if it is not the same as the eclipse battle), the mediation

by Syennesis of Cilicia and Labynetus of Babylon, the marriage of

26

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

Aryene to Astyages and finally, arguably I think, the length of the

war itself. The impression given by Herodotus is that the war lasted

five years, and in the sixth came the eclipse battle which led very

quickly to the establishment of peace. Now it is quite possible that

here Herodotus is using the period of five years as an approximate

rather than as an exact period of time. There are two places where he

uses iretxTTTTi f| fieri] f|npfl to indicate 'a few days later';21 further,

there is one passage which is an exact analogy of the present one;

and this strongly suggests that here also Herodotus is only indicating

a rough period of time,22 so that the figure given here need not be

taken too seriously. In fact there need not be any basic discrepancy

between the Herodotus and the CPS tradition on this point.

There are however some points of disagreement between these

two traditions, (i) The war appears uniformly elsewhere as being

between Alyattes and Astyages; yet in Herodotus it would appear

to have been entirely between Alyattes and Cyaxares.23 (2) We have

seen that Herodotus implies, without actually saying so, that the

peace followed fairly shortly after the eclipse battle. The CPS

tradition, however, gives a period of three years between the eclipse

and the peace (585/4-582/1 B.C.); it may be that Herodotus (like

AV) is confusing the battle which appears in Eusebius under the same

year as the peace in Solinusand is therefore presumably directly

connected with the peacewith the eclipse battle, and attaches the

peace to the wrong one; the fact that his remarks on the connexion

between the eclipse battle and the peace are rather vague may be

due to this confusion. (3) The final point of difference between the

two traditions is that Herodotus makes no mention whatsoever of a

second war between Media and Lydia, but yet such a war seems to

be clearly recorded in Eusebius.24 Perhaps Herodotus has confused

two wars, which took place in quick succession, and rolled them into

one; but on the other hand Eusebius is by no means a thoroughly

reliable source, and one hesitates at this stage to build up too elaborate

a theory on such a basis. One can do little more than bear in mind

the possibility of a second war.

Of these three points of disagreement, the real problem, as Huxley

points out, is posed by the first: who was on the throne of Media

at the time of the earlier war? It is possible to reconcile Herodotus

and the CPS tradition to a certain degree. When Solinus talks of the

peace, he says quite definitely that the war was waged between

Alyattes and Astyages; and there is nothing in the text of

Herodotus that is incompatible with Astyages being on the throne

27

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

of Media by the end of the war, although one might have expected

Herodotus to say that Cyaxares died during the war, if he knew this

to have been sobut the argumentum e silentio is fraught with

danger.25 The Lydians would have felt themselves under all the

greater an obligation to avenge Astyages if the peace had been made

with him rather than with his father; also the marriage of Astyages

and Aryene would not have been so significant if Astyages was not

actually on the throne at the time that it took placethe succession

of a polygamous monarchy was never secure until the successor was

safely established in power. If Astyages was not so established, the

marriage would not have been the avayKcuri icrxupri that Herodotus

says it was.26 We can then accept that Astyages had succeeded his

father at least by the time that the war came to an end.

III

The most recent evidence on the matter is Oxyrhynchus Papyrus

No. 2506 fr. 98. This fragment comes from a commentary on the

lyric poets and appears to discuss whether or not Alcaeus died in a

certain action, together with other things; the part of this fragment

germane to the present issue are lines 14 ff.:27

. . .] 5icc to cruv(cttaa6[ai 14

rr6]Aenov ev [.]lcrr[ 'A

<tt] uayr)i tu [. .]. <p[ 'A

AuccJtttiv oo[

KT

As Huxley says,28 the supplements producing 'Acrruayr)i and

'AAucrrrriv are very cogent, particularly in the light of the evidence

already discussed. Page assigns the papyrus to the first century or

the early part of the second century A.D.29 and this would make it

belong to roughly the same context as Cicero and Pliny, which fits

in nicely as it seems to be drawing on the same tradition.80 In view

of the bad condition of the text, it is difficult to go any further than

to link up 61a to cruviaracjOca ttoAbijov with 'Acrru&yr|i and 'AAvcmriv,

and to take the general sense of the passage to be something like

'. . . because of war being joined (or ' being in progress') [between]

Alyattes [and] Astyages . . .'. Because of the lacunae the exact

significance of the cases of 'Aoru&yr)iand'AAuarrrivis lost; one inter

esting speculation, however, is this: if we take crwiaTacrOai to have

a sense of initiation, the text would imply that a war was begun

28

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

between Astyages and Alyattes; now whatever the obscurity in

Herodotus enshrouding the end of the war there is no doubt that

Cyaxares began it and it would be foolish to mistrust Herodotus on

the point without strong reasons; it is equally clear that the papyrus

fragment should be taken seriously, since the author presumably had

a text of Alcaeus before him. This possible discrepancywhich

admittedly only arises if ovvicrraaQai is taken to have a sense of

initiation31can be resolved if one takes the author of the papyrus

to be referring to the second war between Media and Lydia which

has already been shown to be a possibility (see above p. 24); Eusebius

says quite clearly that this was begun by Astyages against the Lydians.

The other way to deal with this discrepancy is to eliminate it by

taking cruvfcrracrQoci to have the sense of ' continue ', making the phrase

as a whole mean ' since there was a war in progress between Alyattes

and Astyages' or something like that; the text would then refer to

any part of the war after the death of Cyaxares.32 Be the detail what

it may, this papyrus fragment supports the other non-Herodotean

evidence on this war by linking Alyattes and Astyages, and its

authority in all likelihood ultimately goes back to Alcaeus himself.83

IV

We have seen that it is probable that Astyages had succeeded

Cyaxares before the end of the war; however the problem remains

as to who was on the throne at the time of the eclipse battle. Cicero

says that the eclipse took place Astyage regnante while Herodotus

says that it was Cyaxares who fought in the battle when day became

night. The problem is essentially one of chronology. The Herodotean

dates for Cyaxares are 633-594 B.C., and for Astyages 593-559 B.C.,

and as they stand these would involve giving the eclipse a Herodotean

date at least nine years earlier than either the chronographic one or

the real one;34 however since Herodotus does not notice that there

was a considerable overlap between Astyages and Cyrus, whose

accession to the Persian throne took place some time before his over

throw of Astyages, his whole Median chronology may be brought

down eight or nine years; if we do this, we get 586/5 B.C. for

Cyaxares' death35 which suits very well. In the light of this there is

a simple and possible solution to the problem of exactly when Astyages

succeeded. When dealing with the non-Herodotean evidence on this

question, we are for the most part dealing with a chronographic

tradition which, by hellenistic times, would have been aware of eastern

29

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

habits in chronography; now one of these habits used at Babylon

but applied to Persian chronography, at least in later times, was to

reckon the year in which a king died as the accession year of his

successor36 so that it is quite possible for the eclipse to have appeared

in chronographic records as having taken place in the reign of

Astyages,although the king of the time may well have been Cyaxares

provided that Cyaxares died in the same year, which was very

probably the case. This would then account for both traditions.

The general picture, then, is this: There was a war between Lydia

and Media that had been going on for some time before 585 B.C.,

when a battle was halted by the occurrence of a solar eclipse; the

war continued to go on for a further three years, according to a

chronographic tradition going back at least as far as Apollodorus,

and then there appears to have been a final battle; whether or not

one side or the other won a decisive victory in the event we do not

know, but at any rate a peace followed this battle, and the oaths

of this peace were consecrated by the mixing and drinking of the

blood of the two contracting parties. Some time later (five years in

Eusebius) there was a second war between the two powers started by

Astyages for some reason with unknown result. If this second war

did in fact take place, it seems much more probable that the

marriage between Astyages and Aryene was arranged after it rather

than after the earlier war.

Much of the theory just summarised had already been concluded

by Huxley in the article referred to; the aim of this paper has been

to clarify the traditions involved in the extant evidence, and to attempt

to reconcile them. It is important to remember that the reconstruction

of the chronographic tradition, as it stood in Roman times, does not

necessarily bring us any nearer to the actual historical facts of the

episode.87

30

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

Notes

1. For the Herodotean account see Hdt. 1.16.2, 1.74 and 1.103.2. Recent

discussion: D. L. Page in his commentary on Oxyrhynchus Papyrus no. 2506,

frag. 98 (Oxyrhynchus Papyri, 29.44-5); G. L. Huxley, ' A war between Alyattes

and AstyagesGr. Rom. Byz. Stud, vi (1965), 3.201 f.

2. This is now definitely thought to be the eclipse concerned rather than either

of those in 610 and 557 B.C.; see How and Wells, A commentary on Herodotus,

note on 1.74.2; and, more recently, H. Kaletsch, ' Zur Lydischen Chronologie

Historia vii (1958), 15-17. It is in fact highly improbable that Thales ever pre

dicted this eclipse, or any other: see O. Neugebauer, The exact sciences in

antiquity, 142 f.

3. This can be deduced from Diodorus Siculus, 1.5.1, assuming Ol.i.i to be

776/5 B.C.

4. That is, assuming that these two dates come from the same tradition, and

are not two different dates for the same event. This assumption is quite reasonable

in view of Solinus' known dependence on Pliny: see Diehl, ' Julius SolinusRE,

X. 828 f. It is likely that the whole tradition reached Solinus via one or other of

Pliny's works.

5. German translation by Karst, 187.

6. Fotheringham's edition, 178.

7. The dates in A V have been lowered here by one year in each case, since

Ol. 1.1 in this version is a year earlier than in St J. (i.e. it corresponds to the

1240th year of Abraham rather than the 1241st, as in St J.). Both versions put

the birth of Christ in the same year of Abraham (2015), but differ by one in the

Olympic year (194.4 in AV but 194.3 in St /.). This makes it clear that the error

must lie in the Olympic scale rather than in the Abrahamic scale.

8. The fact that St J. puts the eclipse entry a year earlier than Pliny can be

easily explained in terms of the tabular lay-out of the Chronicle. This lay-out

makes it difficult at times to attach entries to their correct year, especially if the

entry is a long one and takes up more space on the page than that opposite one

year. This is a notorious source of corruption in the texts of Eusebius' Chronicle:

see Helm, Eusebius" Werke, VII. xxii (1956 edition).

9. Note St J. says Alyattes et Astyages dimicaverunt, using a word that has the

sense of fighting to a clear conclusion.

10. Hdt. 1.74.1-2.

11. See note 8 above.

12. Solinus, 1.112; he dates the fall of Sardis to OI.58, which can be shown to

be the Apollodoran date for this event from Diogenes Laertius, 1.37, which is

Apollodorus, frag. 28 in Jacoby, Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, II B.

no. 244; for Jacoby's commentary, see F.Gr.H., II D. 726-7.

13. Jacoby, F.Gr.H., II D. 59.

14. See J. E. Powell, The History of Herodotus, 9.

15. Hdt. 1.15 and 1.103.3. See Kretschmer, ' ScythaeRE, II A. 938 f.;

Lehmann-Haupt, ' Kimmerieribid. XI. 404 f.

16. Hdt. 1.16.2; Polyaenus, Stratagemata, 7.2.

17. Hdt. 1.103.3-106.2; cf. St J. under OI.36.2 and AV under OI.36.3.

3i

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

H. M. T. Cobbe

18. The j'VKTo/j.a\ia in 1.74.1 provides an interesting problem: is it the

eclipse battle or not? . How and Wells (see their note ad loc.) maintain, without

giving a reason, that it is not; however it seems very much more probable that it

is and that Herodotus' text at 1.74.2 f. should be taken as an amplification of

iv Se kou vvKTOfxa^LTjv ttva 7rotTjcavTo. Herodotus saw the eclipse as a sudden

appearance of night in the middle of the dayTrjv r/fxiprjv i^airLvrji vvktu ytvtodai

and consequently a battle fought under such conditions would be a vvKTO/xa^ia.

Two such battles in the same war would be highly remarkable, and one would

expect Herodotus to have been much more explicit, if such had taken place.

19. Huxley follows Dougherty (Nabonidus and Belshazzar, 33 f.) in the latter's

solution to the problem posed by the fact that Nabonidus (= Labynetus) did not

succeed to the throne of Babylon until 556 B.C. The problem need not be dis

cussed here except to say that this solution is simpleDougherty shows that it is

quite possible for Nabonidus to have acted as Nebuchadrezzar's agent in this

matter.

20. See p. 22 above.

21. Hdt. 1.1.3; 3.42.1.

22. Hdt. 3.59.2 : t/neivav S'iv ravrrj xal ciSai/uovrjaav iir' irea ircr . . .

fKTa) Se (Tc'i This corresponds almost exactly with the present passage: TroXeyuos

. . . iycyovee i-rr' Ire a wivrt . . . tw !kt<o Irct.

23. Were it not for the other evidence (the CPS tradition) no one would

suspect from Herodotus' account that Cyaxares was not the Median ruler right

through the war until the end. The fact that a change of reign in the middle of

the war is not contradictory to the Herodotean account is only apparent in the

light of the other evidence.

24. See p. 24 above.

25. Hdt. 1.73.1-2. Cyaxares is not mentioned at all in connexion with the peace

in Herodotus; and he is only firmly associated with the eclipse battle later at

1.103.2.

26. Hdt. 1.74.4.

27. For the full text, see Oxyrhynchus Papyri, 29. The question of Alcaeus'

and Antimenidas' involvement in this war is too vague to be profitably discussed

here.

28. Op. cit., 201.

29. Op. cit., 1.

30. Solinus would appear to date to the early third century A.D., cf. Momm

sen's edition of S. (Berlin, 1864), v f.; but he probably drew on Pliny, or, at least,

on an earlier author of about the same time.

31. This depends on whether (rvvivTanrOai is taken to be middle or passive.

If the middle and intransitive sense is taken, iroXt/xov will be the object and the

meaning will be ' since [? Alyattes] contrived [or ' was contriving '] war . . .', cf.

Isocrates, 10.49 and Polybius, 2.1.1 for 7ro\/xov as object of avvio-Taadai. If the

passive and intransitive sense is taken, noXcfuov will be the subject and the mean

ing will be ' since war was in progress . . cf. Thuc. 1.15; Hdt. 7.144 and 8.142.

See Liddell & Scott (Jones-Mackenzie) s.v. <Tvvi<TTH)fii A.III.3 and B.II.i. The

former sense seems to be the better attested of the two for later Greek.

32. The problem of the chronology of the Aeginetan Wars is also one where

the precise sense ofa-vvla-Trj/xi is important; see N. G. L. Hammond, 'Studies in

early Greek chronology ', Historia iv (1955), 408 f.

32

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Alyattes' Median war

33- Huxley, op. cit., 206.

34. H. Strasburger, ' Herodots Zeitrechnungin W. Marg's compilation,

Herodot (Munich, 1962), 689.

35. Cf. Huxley, op. cit., 204; Strasburger, op. cit., 688-9; Kaletsch, op. cit.,

20-23. Cyaxares is established for the years 614 and 612 B.C. from cuneiform

sources (D. Wiseman, Chronicles of the Chaldaean kings in the British Museum,

59, 61), which is well within the limits of the thirty-five years' reign given to

him by Herodotus, i.e. 620-586 B.C. when brought down (see p. 29 above),

and leaves time between the fall of Nineveh (612 B.C.) and the Lydian war for

the Scythian domination; see Wiseman, op. cit., 14 f. The Lydian war probably

followed closely on this if, as has been suggested (see pp. 25-26 above), the Scyths

were the raison d'etre for the war.

36. See R. A. Parker and W. H. Dubberstein, Babylonian chronology 626 B.C.

A.D. 75 (Providence, Rhode Island; 1956). At Babylon the regnal year started on

1 Nisan, and a king's first year did not start until the 1 Nisan following his

accession, the year previous to this being reckoned as his accession year. Whether

the Persians used a similar system before they took Babylon we do not know; it is

doubtful whether the Medes did. The suggestion put forward in the text here

assumes that earlier records were later doctored to conform to Babylonian chrono

graphic conventions.

37. I wish to thank both Mr W. G. Forrest and Mr T. F. R. G. Braun who

read a draft of this paper and made many suggestions of which the greater part

has been incorporated in the text. Professor A. Andrewes very kindly gave me

some information on Babylonian habits in chronography.

33

c

This content downloaded from 188.34.69.149 on Thu, 26 May 2016 23:37:53 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Bebop Scale BasicsDocument3 pagesBebop Scale BasicsSunil Kamat96% (47)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Useful Websites and LinksDocument6 pagesUseful Websites and Linksapi-306276137No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Vulfpeck - Hero TownDocument2 pagesVulfpeck - Hero TownyellowsunNo ratings yet

- Wei Kuen Do PDFDocument7 pagesWei Kuen Do PDFAnimesh Ghosh100% (1)

- Cases To Accompany Contemporary Strategy Analysis - 1405124083Document391 pagesCases To Accompany Contemporary Strategy Analysis - 1405124083Avinash Kumar100% (1)

- T5u4hDocument10 pagesT5u4hJ.ROMERO100% (4)

- Arkan - Genocide in BosnieDocument12 pagesArkan - Genocide in BosniepipanatorNo ratings yet

- A Bibliography On Christianity in EthiopiaDocument105 pagesA Bibliography On Christianity in Ethiopiafábio_homem100% (2)

- Zhu Xiao Mei - The Secret Piano, From Mao's Labor Camps To Bach's Goldberg VariationsDocument166 pagesZhu Xiao Mei - The Secret Piano, From Mao's Labor Camps To Bach's Goldberg Variationsay2004jan50% (2)

- FCE: Use of English: Open Cloze ExercisesDocument4 pagesFCE: Use of English: Open Cloze Exercisesteacher fernando70% (10)

- SOME/ANY/MUCH/MANY/A LOT OF/(A) FEW/(A) LITTLEDocument2 pagesSOME/ANY/MUCH/MANY/A LOT OF/(A) FEW/(A) LITTLEbill pap0% (1)

- Angiosperm or GymnospermDocument2 pagesAngiosperm or Gymnospermtuti_ron_007100% (1)

- Obstructive Jaundice: Laporan KasusDocument29 pagesObstructive Jaundice: Laporan KasusMeyva SasmitaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Czech Violin Makers 08 2007Document3 pagesContemporary Czech Violin Makers 08 2007Sergiu MunteanuNo ratings yet

- Topic Based Vocabulary List PDFDocument47 pagesTopic Based Vocabulary List PDFAnonymous xuyRYU3No ratings yet

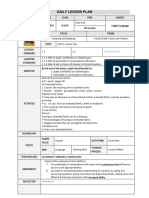

- Daily Lesson Plans for English ClassDocument15 pagesDaily Lesson Plans for English ClassMuhammad AmirulNo ratings yet

- Abellana, Modernism, Locality-PicCompressedDocument70 pagesAbellana, Modernism, Locality-PicCompressedapi-3712082100% (5)

- Elements of DramaDocument15 pagesElements of DramaSukriti BajajNo ratings yet

- Disputers of The Tao-Kwong-Loi ShunDocument4 pagesDisputers of The Tao-Kwong-Loi Shunlining quNo ratings yet

- Ana & Dino Demicheli, Salona AD 541 PDFDocument34 pagesAna & Dino Demicheli, Salona AD 541 PDFAnonymous hXQMt5No ratings yet

- 3d Artist New CVDocument1 page3d Artist New CVMustafa HashmyNo ratings yet

- Fourth Finger Base Joint: BasicsDocument3 pagesFourth Finger Base Joint: BasicsFrancisco Darling Lopes do NascimentoNo ratings yet

- English 393B: Environmental CriticismDocument4 pagesEnglish 393B: Environmental CriticismLuis RomanoNo ratings yet

- Toccata and Fugue in D Minor Trumpet2Document3 pagesToccata and Fugue in D Minor Trumpet2wong chen yikNo ratings yet

- Drifter OP - Guitar Tab Full - AndrosDocument3 pagesDrifter OP - Guitar Tab Full - AndrosSahrul AgustianNo ratings yet

- Graphetic Substance Or, Substance.: Maggie and Milly and Molly and May (Deviation)Document12 pagesGraphetic Substance Or, Substance.: Maggie and Milly and Molly and May (Deviation)Maricris BlgtsNo ratings yet

- High Culture and Subcultures ExplainedDocument1 pageHigh Culture and Subcultures ExplainedMadhura SawantNo ratings yet

- Lourdesian Bookface Online Photo ContestDocument8 pagesLourdesian Bookface Online Photo ContestTerry Gabriel SignoNo ratings yet

- God Damn You'Re Beautiful Piano Sheet MusicDocument13 pagesGod Damn You'Re Beautiful Piano Sheet MusicJonathan Zakagi PhanNo ratings yet

- Kevin LynchDocument3 pagesKevin LynchKevinLynch17No ratings yet