Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Epidemiology of Stillbirth

Uploaded by

Nenny Yoanitha DjalaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Epidemiology of Stillbirth

Uploaded by

Nenny Yoanitha DjalaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Epidemiology of Stillbirth

Sven Cnattingius and Olof Stephansson

Stillbirths account for an increasing proportion of feto-infant mortality. Yet, causes of stillbirth are

rarely reported, and the causes of most stillbirths remain unknown. Few studies focus specifically on

the epidemiology of stillbirth. Major risk factors include high maternal age, smoking, and overweight.

The prevalence of delayed childbearing and, especially overweight, are increasing in most developed

countries. The proportion o f stillbirth attributable to overweight is likely to increase.

Copyright 9 2002 by W.B. Saunders

tillbirth currently accounts for m o r e than

S one third of all feto-infant mortality and

m o r e than 50% o f all perinatal deaths in develo p e d countries. 1,2 A m o n g n o n m a l f o r m e d fetuses/infants, stillbirth at 28 c o m p l e t e d gestational weeks or later accounts for m o r e than

50% of all feto-infant m o r t a l i t y ) Moreover, the

causes of stillbirth differ f r o m those of early

neonatal mortality, z,4 Despite the clear importance of stillbirth as a public health problem, few

studies have focused specifically on the epidemiotogy and cause of stillbirth.

Causes

In contrast to infant mortality, causes of stillbirth

are generally not registered i n vital statistics or

population-based research registers. T h e r e are

also substantial difficulties in d e t e r m i n i n g the

cause of stillbirth. First, weight a n d gestational

length are, in the case of a stillbirth, estimated at

delivery and not at time of death. This leads not

only to an overestimation of gestational length,

but the fetus may also have lost weight after

death. Thus, the i m p o r t a n c e of low birth weight

in relation to gestational age may therefore be

overestimated in stillbirth. Second, even if diagnostic investigations are p e r f o r m e d , there may

be difficulties in achiex4ng valid results. Pathological investigations must consider possible

changes occurring between the often u n k n o w n

time of death and time of investigation. W h e n

looking for an infectious cause, it may be unknown what infections should be considered lethal, and infections may also occur during or

after delivery.

A n u m b e r of m e t h o d s of g r o u p i n g causes of

death in stillbirth a n d neonatal deaths have

b e e n used. 5,6 T h e cause of stillbirth differs in

m a n y cases f r o m the cause of neonatal deaths,

which necessitates a specific classification system

for stillbirth. More importantly, diagnostic routines generally differ substantially between hospitals, and a successful classification of causes of

stillbirth is highly d e p e n d e n t on a standardized

and systematic clinical procedure. As m o r e than

1 factor may contribute to fetal death, m a n y

classifications have recognized the n e e d for a

hierarchical classification system, in which potentially lethal anomalies take p r e c e d e n c e over

other conditions. 5,6 Two o t h e r i m p o r t a n t causes

of stillbirth are prenatal infections, and above

all, fetal growth retardation. O t h e r causes include isoimmunization, abruptio placenta, maternal chronic diseases, pregnancy-related disorders (such as preeclampsia and gestational

diabetes), and umbilical cord accidents. Yet, despite all these possible causes o f stillbirth, a

substantial p r o p o r t i o n of stillbirths r e m a i n

unexplained. However, within the g r o u p of "unexplained" stillbirths, there is probably a relatively large g r o u p of fetuses with undiagnosed

fetal malnutrition, c h r o m o s o m a l aberrations, or

infections.

Stillbirth and G e s t a t i o n a l A g e

W h e n stillbirth is defined as a fetal death occurring at 20 weeks or later, 82% of all stillbirths are

r e p o r t e d to occur in the p r e t e r m period. 7 Also,

when stillbirth is defined as fetal death at 24

weeks or later or even at 28 weeks or later, the

From the Department of Medical Epidemiology, Karolinska Instituter, Stockholm.

Address ~'eprint requests to Sven Cnattingius, MD, PhD, Department

of Medical Epidemiology, Karolinska Instituter, PO Box 281, SE171 77 StockhoZm; e-mail: Sven. Cnattingius@mep.ki.se.

Copyright 9 2002 by W.B. Saundev's

O146-0005/02/2601-0005535. 00/0

doi:l O.1053/sper.2002.29841

Seminars in Perinatology, Vol 26, No 1 (February), 2002: pp 25-30

25

Cnattingius and Stephansson

26

majority of stillbirth occur preterm. 8,9 Since the

majority of stillbirths occur preterm, it may seem

paradoxical that the risk of stillbirth increases

with gestational age. However, as p o i n t e d out by

Yudkin et al, 1~ fetuses at risk of stillbirth at a

specific gestational age must include all live fetuses at that gestational age. By using this approach, Yudkin et aP ~ showed a consistent increase in risk of stillbirth by gestational age (Fig

1), an observation that has b e e n c o n f i r m e d by

o t h e r investigators, n,12 Thus, the risk of stillbirth

may be highest in the postterm period, which to

a large extent can be explained by increased

rates of small-for-gestational-age fetuses b o r n

postterm. 1~

Risk F a c t o r s

Maternal Age

T h e r e is g o o d evidence that it is b e c o m i n g increasingly c o m m o n a m o n g w o m e n to choose to

delay childbearing. In the United States, the

p r o p o r t i o n of first-time mothers who were age

30 or older increased f r o m 4% in 1969 to 21% in

1994.14 -The t r e n d of delayed childbearing has

occurred primarily a m o n g w o m e n with at least

high school education and is attributed to

w o m e n voluntarily p o s t p o n i n g pregnancies for

personal or professional reasons. Several large

epidemiological studies have r e p o r t e d that high

2,0

1s

1,e

o

Q

1,4

1,2

~, 0,8

0,6

Table 1. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence

Intervals (CI) for Stillbirth by Maternal Age

Age (years)

OR

(95 % CI)

(reference group)

<30

1.0

30-34

1.3

(0.9-1.7)

35-39

40+

1.9

2.4

(1.3-2.7)

(1.3-4.5)

Data from reference 16.

m a t e r n a l age increases the risk of stillbirth. 15,16

Fretts et aP 6 r e p o r t e d that, c o m p a r e d to w o m e n

below 30 years, the risk of fetal d e a t h a m o n g

w o m e n aged 35 to 39 years was almost increased

24bld, while c o r r e s p o n d i n g risk for those 40 or

older was m o r e than doubled (Table 1). T h e risk

of stillbirth is especially p r o n o u n c e d a m o n g delayed childbearers, but probably also increased

a m o n g older parous women. Although the risks

of pregnancy-related disorders or complications,

such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, a n d

abruptio placenta increase with age, the agerelated increase in stillbirth cannot be explained

by these diseases, a2,a6 T h e age-related stillbirth

risk increases with advancing gestational age,

and older w o m e n have above all an increased

risk of u n e x p l a i n e d s t i l l b i r t h / A l t h o u g h the absolute increase in risk for the individual w o m a n

may be considered modest, the i m p a c t of delayed childbearing becomes m o r e i m p o r t a n t as

the p h e n o m e n o n b e c o m e s m o r e prevalent.

T e e n a g e pregnancies are, in contrast to high

m a t e r n a l age, m o r e associated with neonatal

death than stillbirthJ 7 This is not surprising,

since the risk of p r e t e r m birth, and especially

very p r e t e r m birth, is increased a m o n g teenage

childbearers (and especially very y o u n g teenagers), while the association between restricted

fetal growth and teenage childbearing is m o r e

controversial.IS

Parity

0,4

0,2

0,0

29

31

33

35

37

39

41

Gestationel age (weeks)

Figure l. Rate of stillbirth by gestational age, per

1,000 live fetuses at that gestational age. (Reprinted

with permission. I~)

Studies have r e p o r t e d an increased rate of stillbirth a m o n g nulliparas and g r a n d multiparas. n,m However, in 1 study, the U-shaped pattern between parity and stillbirth risk was,

a m o n g older women, evident in the t960s a n d

early 1970s, but not in the late 1970s and

1980s/6 T h e authors suggest that the reduction

in the parity-related risk of stillbirth over time

Epidemiology of Stillbirth

may be due to i m p r o v e d access to medical care

and changes of obstetrical practice.

Smokmg

T h e association between smoking and stillbirth

risk is well known and there is probably a causal

association. First, the risk of stillbirth increases

with the a m o u n t smoked. 2,2~ Second, there is a

supportive biological hypothesis. Smoking during pregnancy increases fetal carboxihemoglobin concentration and increases the vascular resistance, because of the vasoconstrictive effect of

nicotine and the r e d u c e d prostacyclin synthesis. 2~-23These toxic effects of tobacco smoke may

partly explain the causal association between

smoking and r e d u c e d fetal growthY 4 These effects may also contribute to the placental

changes a m o n g smokers, such as decidual necrosis, which in turn may lead to abruptio placenta. 25"26 In a study of Meyer a n d Tonascia, 27

the elevated risk of fetal death in smokers was

largely because of higher rates of placental abruption and placenta previa. A n o t h e r study

f o u n d a 40% overall increased risk of stillbirth

a m o n g smokers, but smokers who did not suffer

f r o m placental complications or delivered

growth retarded infants had no increased risk of

stillbirth, t2 Thus, it appears that the association

between smoking and stillbirth is explained by

the smoking-related risks of fetal growth retardation and placental complications. Third, the

hypothesis of a causal association between smoking during pregnancy and stillbirth is further

s t r e n g t h e n e d by a recent Danish study, reporting that smoking cessation in the first trimester

reduces the risk of stillbirth c o r r e s p o n d i n g to

that of nonsmokers. 23 This result also indicates

that smoking exerts its influence on stillbirth

after the first trimester. Smoking has b e e n rep o r t e d to primarily influence risk of p r e t e r m

stillbirth, ~2 and these results are in turn supp o r t e d by a finding that intrauterine growth retardation is a stronger risk factor for p r e t e r m

than for term stillbirth, s

Although the prevalence of smoking during

p r e g n a n c y has declined in m a n y countries, still

between 10% to 30% of the p r e g n a n t population in the western world smoke. 23,29 Thus,

smoking continues to be one of the most important preventable risk factors for stillbirth.

27

Maternal Body-mass Index

An association between maternal body-mass index (BMI) and stillbirth risk, with the highest

risk a m o n g overweight and obese w o m e n was

r e p o r t e d in 1993. 2o A Swedish register-based

study confirmed this and f o u n d that the association between increasing BMI and stillbirth risk

was highest a m o n g nutliparous women. 3~ A recent Swedish study on a n t e p a r t u m stillbirths

f o u n d that the association between early pregnancy BMI and stillbirth risk was strongest for

term stillbirths, suggesting an increasing effect

of a high BMI by gestational length. 31 T h e mechanisms for the BMI-related increases in risk of

stillbirth remain a matter of speculation. Overweight and obese w o m e n are m o r e likely to have

a low socio-economic status a n d are m o r e often

cigarette smokers. Pregnancy complications,

such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and

eclampsia, are m o r e c o m m o n a m o n g overweight

and obese women. After excluding cases and

controls with weight-related pregnancy complications, the risk of stillbirth r e m a i n e d increased

a m o n g overweight women, but was attenuated

a m o n g obese w o m e n (Table 2). 3~ T h e prevalence of overweight and obesity is rising rapidly

in developed countries (Fig 2), 32 and in the

United States a third of the p r e g n a n t population

are overweight (BMI > 25). as If causal, overweight may f r o m a public health perspective be

the most i m p o r t a n t risk factor for stillbirth.

Table 2. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence

Intervals (CI) for Antepartum Stillbirth by Bodymass Index (BMI) Among Nulliparous Women

All Cases and

Controls

(n = 613/660)*

BMI

-<19.9++

20.0-24.9

25.0-29.9

-->30.0

Excluding Cases

and Controls With

Gestational

Diabetes and

Preeclampsia

(n = 461/546)*

OR~

(95 % CI)

OR~

(95 % CI)

1.0

1.2

1.9

2.1

(0.8-1.7)

(1.2-2.9)

(1.2-3.6)

1.0

1.2

2.5

1.5

(0.8-1.8)

(1.5-4.0)

(0.7-3.0)

* Number of cases/controls.

t Adjusted for age, height, occupation, and cigarette smoking.

++Reference group.

Data from reference 31.

Cnattingius and Stephansson

28

%

20

15

D MI 25.0-29,9

[] BMI 30.0-34.9

10

[] BMI 35.0+

5

0

1960-62

1971-74

1976-80

1988-94

Figure 2. Prevalence of overweight and obesity

among women aged 20-29 years, United States 19601994. (Data from reference 32.)

Maternal Weight Gain During Pregnancy

Few studies have investigated the association between weight gain during pregnancy and stillbirth risk. Weight gain is related to prepregnancy BMI, and w o m e n with a high BMI gain

less weight during p r e g n a n c y ? T M Therefore, it

is i m p o r t a n t when analyzing the association between weight gain a n d risk of stillbirth to consider p r e p r e g n a n c y BMI as a c o n f o u n d i n g factor. Taffel et a135 showed an association between

low m a t e r n a l weight gain and stillbirth risk,

whereas-this was not f o u n d by Rydhstr6m et al. ~6

However, n o n e of these studies simultaneously

investigated the possible influences by other covariates. A recent Swedish study was able to take

such confounders into account and f o u n d no

association between pregnancy weight gain a n d

a n t e p a r t u m stillbirth risk. 31

Socio-economic Factors

Although it is generally known that socio-economic status influences stillbirth risk, 2~ the reasons remain essentially unknown. This is not

entirely because most studies have included few

covariates, but results f r o m a recent study suggest that the reasons for the association may be

h a r d to disentangle. 9 T h e group of w o m e n f r o m

low social class was favored by a reduced prevalence of delayed childbearers, but, on the o t h e r

hand, they were m o r e often smokers and overweight. Thus, the risks of stillbirth related to low

socio-economic status, were after adjustment for

maternal age, smoking and body mass index,

essentially the same as the crude risks. Moreover,

further adjustments for time of admittance to

antenatal care, n u m b e r of visits to prenatal care,

and a n u m b e r of o t h e r covariates, did not essentially c h a n g e these risks, n o r were the risks

e x p l a i n e d by i n c r e a s e d rates o f small-for-

gestational-age pregnancies or pregnancy-related disorders a m o n g w o m e n f r o m low social

class9 Residual c o n f o u n d i n g of alcohol a n d illicit drug use is a possible but not p r o b a b l e

explanation. Since the risk related to low social

class was primarily increased for t e r m stillbirth,

one may hypothesize whether these differences

are due to subtle differences in care.

Recurrent Stillbirth

T h e tendency to repeat pregnancy o u t c o m e s in

successive births is well known and also includes

risk of stillbirth. W o m e n with a previous stillbirth may, c o m p a r e d to w o m e n with no previous

stillbirth, have a 6 to 10-fold increased risk of

stillbirth in next pregnancy. 37,3s Although recurrence of stillbirth is m o r e c o m m o n a m o n g

w o m e n with diabetes or pregnancy-induced hypertensive diseases, and may also be associated

with recurrence of fetal growth retardation, such

factors probably only partly explain the risk of

repeating stillbirth, s7-~9

Maternal Hemoglobin Concentration

During normal pregnancy, the h e m o g l o b i n concentration falls until the 20th week of gestation,

remains fairly constant up to 30 weeks and thereafter rises slightly. These changes in h e m o g l o b i n

concentration are mainly due to an increased

plasma volume. In developed countries, b o t h

high a n d low h e m o g l o b i n concentration during

p r e g n a n c y have b e e n associated with small-forgestational-age and p r e t e r m births. Two studies

have r e p o r t e d increased rates of perinatal death

with b o t h low and high h e m o g l o b i n concentration during pregnancy, 4~ and 1 study f o u n d a

similar u-shaped association for stillbirth rates. 42

In a recently published study the risk of stillbirth

was increased for b o t h low (--<115 g / L ) and high

(>--146 g / L ) early pregnancy h e m o g l o b i n concentration, 43 and a relatively large decrease in

h e m o g l o b i n concentration during p r e g n a n c y

t e n d e d to be protective. T h e risk related to high

h e m o g l o b i n values was confined to a n t e p a r t u m

stillbirths without malformations, and especially

p r o n o u n c e d if the fetus also was growth-retarded (Table 3). T h e biological m e c h a n i s m for

the increased risk of stillbirth for high h e m o g l o bin concentration may be that plasma expansion

enhances fetal growth. T h e r e d u c e d b l o o d viscosity may favor b l o o d flow in the m a t e r n a l in-

Epidemiology of Stillbirth

T a b l e 3. O d d s Ratio (OR) a n d 95% C o n f i d e n c e

Intervals (CI) for Stillbirth by H e m o g l o b i n

C o n c e n t r a t i o n in First T r i m e s t e r

Antepmr

Stillbirth Without

Malformations

All

(n = 519/610)*

SGA-stillbirths

(n = 137/390)*

First Hb g/L

ORt

(95% CI)

OR?

(95% CI)

--<115

116-125

126-135 (ref.)

136-145

-->146

1.7

0.9

1.0

1.0

2.0

(1.0-2.8)

(0.6-1.2)

1.5

0.4

1.0

1.1

4.2

(0.6-3.9)

(0.2-0.8)

(0.7-1.4)

(1.1-3.8)

(0.6-2.1)

(1.3-13.9)

* Number of cases and controls.

t Adjusted for age, height, BMI, occupation, smoking, early

pregnancy weekly change in Hb, and week of first Hb measurement.

Source: Stephanssou et al. JAMA 2000;284:2611-7.

tervillous space and prevent thrombosis in the

uteroplacental circulation.

Multiple Birth

Since twins are m o r e likely to be growth-retarded and to be delivered preterm, they have an

increased risk of stillbirth and (above all) neonatal death. A particular concern is monozygotic

twins, who have p o o r e r survival than dizygotic

twins. 44,45 If 1 twin dies in utero, the cotwin is n o t

only at increased risk of fetal death, but also runs

an increased risk of cerebral palsy and o t h e r

cerebral impairments. 44 The relative i m p o r t a n c e

of twin pregnancy as a risk factor for stillbirth is

likely to increase, as the rate of twin pregnancies

are increasing. 46

Conclusions

In contrast to infant mortality, the decline in

stillbirth rates have, in most countries, b e e n less

obvious. The majority of stillbirths dies unexpectedly preterm, when possibilities to detect

warning signs, such as fetal growth restriction,

are limited. Major maternal risk factors include

m a t e r n a l smoking, high maternal age, and overweight, but why high maternal a g e and overweight influence stillbirth risk remains to be

determined. In contrast to smoking, the prevalence of delayed childbearing and overweight

are increasing in most developed countries.

29

Thus, the relative i m p o r t a n c e of these factors is

likely to increase.

References

1. Kalter H: Five-decade international trends in the relation of perinatal mortality and congenital malformations: Stillbirth and neonatal death compared. IntJ Epidemiol 20:173-179, 1991

2. KleinmanJC, Pierre MBJr., MadansJH, et al: The effects

of maternal smoking on fetal and infant mortality. AmJ

Epidemiol 127:274-282, 1988

3. Cnattingias S, Haglund B, Kramer MS: Differences in

late fetal death rates in association with determinants of

small for gestational age fetuses: Population based cohort study. BMJ 316:1483-1487, 1998

4. Naeye RL: Maternal age, obstetric complications, and

the outcome of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 61:210-216,

1983

5. Fretts RC, Usher RH: Causes of fetal death in women of

advanced maternal age. Obstet Gynecol 89:40-45, 1997

6. Lammer EJ, Brown LE, Anderka MT, et al: Classification

and analysis of fetal deaths in Massachusetts. JAMA 261:

1757-1762, 1989

7. Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, DuBard MB, et al: Risk

factors for fetal death in white, black, and Hispanic

women. Collaborative Group on Preterm Birth Prevention. Obstet Gynecol 84:490-495, 1994

8. Gardosi J, Mul T, Mongelli M, et al: Analysis of birthweight and gestational age in antepartum stillbirths. BrJ

Obstet Gynaecol 105:524-530, 1998

9. Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson ALV, et al: The

influence of socioeconomic status on risk of stillbirth in

Sweden. I n t J Epidemiol 2001

10. Yudkin PL, Wood L, Redman CW: Risk of unexplained

stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet 1:11921194, 1987

11. Huang DY, Usher RH, Kramer MS, et al: Determinants

of unexplained antepartum fetal deaths. Obstet Gynecol

95:215-221, 2000

12. Raymond EG, Cnattingius S, KielyJL: Effects of maternal

age, parity, and smoking on the risk of stillbirth. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol 101:301-306, 1994

13. Clausson B, Cnattingius S, Axelsson O: Outcomes of

post-term births: the role of fetal growth restriction and

malformations. Obstet Gynecol 94:758-762, 1999

14. Heck KE, Schoendorf KC, Ventura SJ, et al: Delayed

childbearing by education level in the United States,

1969-1994. Matern Child HealthJ 1:81-88, 1997

15. Cnattingius S, Forman MR, Berendes HW, et al: Delayed

childbearing and risk of adverse perinatal outcome. A

population-based study. JAMA 268:886-890, 1992

16. Fretts RC, Schmittdiel J, McLean FH, et al: Increased

maternal age and the risk of fetal death. N Engl J Med

333:953-957, 1995

17. Olausson PO, Cnattingius S, Haglund B: Teenage pregnancies and risk of late fetal death and infant mortality.

BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 106:116-121, 1999

18. Fraser AM, BrockertJE, Ward RH: Association of young

maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes.

N EnglJ Med 332:1113-1117, 1995

30

Cnattingius and Stephansson

19. Kiely JL, Paneth N, Susser M: An assessment of the

effects of maternal age and parity in different components of perinatal mortality. Am J Epidemiol 123:444454, 1986

20. Little RE, Weinberg CR: Risk factors for antepartum and

intrapartum stillbirth. Am J Epidemiol 137:1177-1189,

1993

21. Ahlsten G, Ewald U, Tuvemo T: Maternal smoking reduces prostacyclin formation in human umbilical arteries. A study on strictly selected pregnancies. Acta Obstet

Gynecol Seand 65:645-649, 1986

22. Longo LD: Carbon monoxide: Effects on oxygenation of

the fetus in utero. Science 194:523-525, 1976

23. Morrow RJ, Ritchie JW, Bull SB: Maternal cigarette

smoking: The effects on umbilical and uterine blood

flow velocity. A m J Obstet Gynecol 159:1069-1071, 1988

24. Kramer MS: Intrauterine growth and gestational duration determinants. Pediatrics 80:502-511, 1987

25. Kramer MS, Usher RH, Pollack R, et al: Etiologic determinants of abruptio placentae. Obstet Gynecol 89:221226, 1997

26. Naeye RL: Abruptio placentae and placenta previa: Frequency, perinatal mortality, and cigarette smoking. Ob,stet G}naecol 55:701-704, 1980

27. Meyer MB, Tonascia JA: Maternal smoking, pregnancy

complications, and perinatal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 128:494-502, 1977

28. Wisborg K, Kesmodel U, Henriksen TB, et al: Exposure

to tobacco smoke in utero and the risk of stillbirth and

death in the first year of life. Am J Epidemiol 154:322327, 2001

29. Cigarette smoking among pregnant women and gMs. In:

Women and smoking--a report from the Surgeon General Rockville, MD, Department of Health and Human

Services, 2001, pp 71-73

30. Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, et ah Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N EnglJ Med 338:147-152, 1998

31. Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A, et al: Maternal weight, pregnancy weight gain, and the risk of antepartum stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:463-469,

2001

32. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, et al: Overweight

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends,

1960-1994. IntJ Obes Relat Metab Disord 22:39-47, 1998

Galtier-Dereure F, Boegner C, Bringer J: Obesity and

pregnancy: Complications and cost. Am J Clin Nutr

71:1242S-1248S, 2000

Abrams B, Carmichael S, Selvin S: Factors associated

with the pattern of maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 86:170-176, 1995

Taffel SM: Maternal weight gain and the outcome of

pregnancy. Vital Health Star 21:1-25, 1986

Rydhstrom H, Tyden T, Herbst A, et al: No relation

between maternal weight gain and stillbirth. Acta Obstet

Gynecol Scand 73:779-781, 1994

Cnattingius S, Berendes HW, Forman MR: Do delayed

childbearers face increased risks of adverse pregnancy

outcomes after the first birth? Obstet Gynecol 81:512516, 1993

Samueloff A, Xenakis EM, Berkus MD, et al: Recurrent

stillbirth. Significance and characteristics. J Reprod Med

38:883-886, 1993

Freeman RK, Dorchester W, Anderson G, et al: The

significance of a previous stillbirth. AmJ Obstet Gynecol

151:7-13, 1985

MurphyJF, O'Riordan J, Newcombe RG, et al: Relation

of haemoglobin levels in first and second trimesters to

outcome of pregnancy. Lancet 1:992-995, 1986

Naeye RL: Placental infarction leading to fetal or neonatal death. A prospective study. Obstet Gynecol 50:583588, 1977

Garn SM, Ridella SA, Petzold AS, et ah Maternal hematologic levels and pregnancy outcomes. Semin Perinatol

5:155-162, 1981

Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A, et al: Maternal hemoglobin concentration during pregnancy and

risk of stillbirth. JAMA 284:2611-2617, 2000

Pharoah PO, Adi Y: Consequences of in-utero death in a

twin pregnancy. Lancet 355:1597-1602, 2000

West CR, Adi Y, Pharoah PO: Fetal and infant death in

mono- and dizygotic twins in England and Wales 198291. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 80:F217-F220, 1999

Ventura SJ, MartinJA, Curtin SC, et ah Births: final data

for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep 48:1-100, 2000

You might also like

- Association Between MRNA Expression of Aromatase 1Document8 pagesAssociation Between MRNA Expression of Aromatase 1Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care - Modul NennyDocument31 pagesPalliative Care - Modul NennyNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

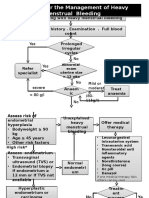

- Algorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingDocument2 pagesAlgorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- En Endometrial Cancer Guide For PatientsDocument30 pagesEn Endometrial Cancer Guide For PatientsNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Hypertensionin PregnancyDocument100 pagesHypertensionin Pregnancyricky hutagalungNo ratings yet

- Estimated Fetal Weight Formula GuideDocument5 pagesEstimated Fetal Weight Formula GuideNenny Yoanitha Djala100% (1)

- Night Shift Duty 11 FEBRUARIDocument2 pagesNight Shift Duty 11 FEBRUARINenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- AJOG 2008 - Amoxicillin Pharmacokinetics in Pregnant WomenDocument6 pagesAJOG 2008 - Amoxicillin Pharmacokinetics in Pregnant WomenNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Program Kerja Gugus Kendali Mutu SMF Obstetri dan Ginekologi 2017-2018Document1 pageProgram Kerja Gugus Kendali Mutu SMF Obstetri dan Ginekologi 2017-2018Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Reichman 2014Document5 pagesReichman 2014Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Algorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingDocument2 pagesAlgorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Volume 207 Issue 3 2012 (Doi 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.031) McPherson, Jessica A. Odibo, Anthony O. Shanks, Anthony L. Ro - Impact of Chorionicity On R PDFDocument6 pagesAmerican Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Volume 207 Issue 3 2012 (Doi 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.031) McPherson, Jessica A. Odibo, Anthony O. Shanks, Anthony L. Ro - Impact of Chorionicity On R PDFNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Forceps Review in Modern Obstetric PracticeDocument5 pagesForceps Review in Modern Obstetric PracticeNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Strategi Bisnis KorporasiDocument41 pagesStrategi Bisnis KorporasiAliMu'minHarahapNo ratings yet

- Termination Pregnancy Report 18 May 2010Document45 pagesTermination Pregnancy Report 18 May 2010Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Obstetrical Forceps - History Mystery and MoralityDocument16 pagesObstetrical Forceps - History Mystery and MoralityNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Medical Eligibility Criteria For Contraceptive Use Fifth Edition 2015Document14 pagesMedical Eligibility Criteria For Contraceptive Use Fifth Edition 2015agustinasntNo ratings yet

- How To Explore After Forceps ExtractionDocument7 pagesHow To Explore After Forceps ExtractionNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Anatomical Causes Bad Obstetric HistoryDocument3 pagesAnatomical Causes Bad Obstetric Historykyle31No ratings yet

- Fetal and Maternal Effects of Forceps and VacuumDocument4 pagesFetal and Maternal Effects of Forceps and VacuumNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Final Data 2011 PDFDocument90 pagesFinal Data 2011 PDFNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Reichman 2014Document5 pagesReichman 2014Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Trali Dari Ats JournalDocument2 pagesTrali Dari Ats JournalNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Algorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingDocument2 pagesAlgorithm For The Management of Heavy Menstrual BleedingNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus Infection in Patients With Active InflammatoryDocument7 pagesCytomegalovirus Infection in Patients With Active InflammatoryNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Forceps ExtractionDocument49 pagesForceps ExtractionNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Study of TORCH Infections in Women With BOH PDFDocument6 pagesGenetic Study of TORCH Infections in Women With BOH PDFNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Reichman 2014Document5 pagesReichman 2014Nenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- Successful Pregnancy OutcomeDocument6 pagesSuccessful Pregnancy OutcomeNenny Yoanitha DjalaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 3rd Annual Radiology For Non-Radiologists (5-6 Oct 2019)Document2 pages3rd Annual Radiology For Non-Radiologists (5-6 Oct 2019)itnnetworkNo ratings yet

- General Pathology MCQDocument3 pagesGeneral Pathology MCQSooPl33% (3)

- Cephalometric Evaluation of GrowthDocument79 pagesCephalometric Evaluation of GrowthAhmedsy Ahmedsy AhmedsyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Specimen Management: A Descriptive Study of 648 Adverse Events and Near MissesDocument7 pagesSurgical Specimen Management: A Descriptive Study of 648 Adverse Events and Near MissesRubia Sari Mamanya HaristNo ratings yet

- Velammal VistDocument30 pagesVelammal VistpriyaNo ratings yet

- Notification Babu Jagjivan Ram Memorial Hospital SR Resident PostsDocument5 pagesNotification Babu Jagjivan Ram Memorial Hospital SR Resident PostsJeshiNo ratings yet

- 04.03-02 Endocrine IV - Uterine Pharmacology PDFDocument4 pages04.03-02 Endocrine IV - Uterine Pharmacology PDFMaikka IlaganNo ratings yet

- Gestational AgeDocument4 pagesGestational AgeNadya Nur AqilahNo ratings yet

- Placenta Previa MarginalDocument50 pagesPlacenta Previa MarginalMedy WedhanggaNo ratings yet

- Vandykediann ResumeDocument3 pagesVandykediann ResumeHARSHANo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument21 pagesBibliographyapi-204960846No ratings yet

- Kangaroo Joey ManualDocument16 pagesKangaroo Joey ManualCarmen Leiva AsencioNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Utilization of Maternal Health CDocument8 pagesFactors Affecting Utilization of Maternal Health CYussufNo ratings yet

- Case presentation on short stature and pubertal delay in a 14-year-old maleDocument27 pagesCase presentation on short stature and pubertal delay in a 14-year-old maledidu91No ratings yet

- Live Before You DieDocument6 pagesLive Before You DieCharms CabauatanNo ratings yet

- Third Stage of Labour Lastt Last LastDocument30 pagesThird Stage of Labour Lastt Last LastAyanayuNo ratings yet

- CV Elective Program For International StudentsDocument5 pagesCV Elective Program For International StudentsYosafatPrasetyadiNo ratings yet

- ISICAM TimetableDocument8 pagesISICAM TimetableMichael SusantoNo ratings yet

- 2018 UNICEF Eswatini Neonatal GuidelinesDocument180 pages2018 UNICEF Eswatini Neonatal GuidelinesTrishenth FonsekaNo ratings yet

- Smart Solutions For OB/GYN: ACUSON X Family and ACUSON P Family Ultrasound SystemsDocument8 pagesSmart Solutions For OB/GYN: ACUSON X Family and ACUSON P Family Ultrasound SystemsPopescu ValiNo ratings yet

- Maquet LyraDocument12 pagesMaquet LyraMiguel YepesNo ratings yet

- Botiss Maxgraft Bonebuilder SurgicalGuideDocument11 pagesBotiss Maxgraft Bonebuilder SurgicalGuideDemmy WijayaNo ratings yet

- Periodontal FlapsDocument65 pagesPeriodontal FlapsSaleh AlsadiNo ratings yet

- KAREEN PRC FILE Corrected FinalDocument10 pagesKAREEN PRC FILE Corrected Finaljedkath2008No ratings yet

- Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia Anaesthetic ConsideDocument3 pagesTraumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia Anaesthetic ConsideHalim SudonoNo ratings yet

- Mccee QuestionsDocument69 pagesMccee QuestionsAndre R. Reynolds Anglin100% (3)

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (Tens) and Pain ManagementDocument54 pagesTranscutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (Tens) and Pain ManagementhashfiluthfihNo ratings yet

- 2017.104 - The - Leopold - Maneuver - PosterDocument1 page2017.104 - The - Leopold - Maneuver - PosterRey CelNo ratings yet

- Facial ContoursDocument20 pagesFacial Contourscmkflorida7011100% (1)

- Plan of The Course Anatomy and Clinical Anatomy: Academic Year 2013/2014Document7 pagesPlan of The Course Anatomy and Clinical Anatomy: Academic Year 2013/2014Rinor MujajNo ratings yet