Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States v. Rodriguez, C.A.A.F. (2004)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States v. Rodriguez, C.A.A.F. (2004)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

UNITED STATES, Appellee

v.

Esteven E. RODRIGUEZ, Private

United States Marine Corps, Appellant

No. 04-5003

Crim. App. No. 200200740

United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces

Argued April 27, 2004

Decided June 30, 2004

BAKER, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which

CRAWFORD, C.J., GIERKE, EFFRON, AND ERDMANN, JJ., joined.

Counsel

For Appellant:

(argued).

Lieutenant Colin A. Kisor, JAGC, USNR

For Appellee: Captain Wilbur Lee, USMC (argued); Colonel

Michael E. Finnie, USMC (on brief).

Military Judges: S. A. Folsom and R. C. Harris

THIS

OPINION IS SUBJECT TO EDITORIAL CORRECTION BEFORE FINAL PUBLICATION.

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

Judge BAKER delivered the opinion of the Court.

Appellant was tried by a military judge sitting as a

general court-martial.

He was convicted in accordance with

his pleas of conspiracy to commit larceny, false official

statements, wrongfully selling and disposing of military

property, wrongful appropriation, and larceny, in violation

of Articles 81, 107, 108, and 121, Uniform Code of Military

Justice [hereinafter UCMJ], 10 U.S.C. 881, 907, 908, and

921 (2000), respectively.

Appellants sentence was

adjudged on October 19, 2000, and included a dishonorable

discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances,

confinement for three years and a fine of $2,000.

Appellants plea agreement obligated the convening

authority to suspend all confinement over 24 months.

On

June 29, 2001, the convening authority ultimately approved

the sentence as adjudged except for the fine.

He also

suspended all confinement in excess of what Appellant would

serve as of December, 15, 2001.

The Court of Criminal

Appeals affirmed the findings and sentence in an

unpublished opinion.

United States v. Rodriguez, NMCCA

200200740, slip op. at 8 (N-M. Ct. Crim. App. Nov. 26,

2003).

The Judge Advocate General of the Navy certified the

following issue to this Court:

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

WHETHER THE NAVY-MARINE CORPS COURT OF CRIMINAL

APPEALS ERRED WHEN IT FOUND THAT THE PORTION OF

THE TRIAL COUNSELS SENTENCING ARGUMENT COMPARING

PRIVATE RODRIGUEZ ACTIONS TO A LATIN MOVIE WAS

MERELY A GRATUITOUS REFERENCE TO RACE AS

OPPOSED TO AN ARGUMENT BASED UPON RACIAL ANIMUS

AND THEREFORE DID NOT REQUIRE REVERSAL OF THE

SENTENCE.

Based on the specific facts of this case, including

the nature of the improper argument and the fact that it

occurred before a judge alone during sentencing, we

conclude Appellant did not suffer material prejudice to a

substantial right as a result of trial counsels improper

argument.

Background

According to his brief, Appellant is of Mexican

descent and is Latino.

At the time of trial, Appellant

was a 21-year-old private, and married with one child.

During closing argument on sentencing before the military

judge, trial counsel stated: These are not the actions of

somebody who is trying to steal to give bread so his child

doesnt starve, sir, some sort of a [L]atin movie here.

These are the actions of somebody who is showing that he is

greedy.

Trial counsels closing statement covers

approximately three and one half pages in the record.

The

comment in question appears half way through the first page

of the statement.

Defense counsel objected to trial

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

counsels argument regarding the use of the term steal

and on the ground that trial counsel was commenting on

pretrial negotiations.

Defense counsel did not object to

the prosecutors reference to some sort of a [L]atin

movie.

The Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) discern[ed] no

logical basis for the trial counsels [L]atin movie

comment.

Rodriguez, NMCCA 200200740, slip op. at 6.

As a

result, the CCA concluded that the comment was improper

and erroneous.

Id.

However, the CCA also stated that the

comment was merely a gratuitous reference to race, it

was not an argument based upon racial animus, nor was it

likely to evoke racial animus.

Id.

The CCA tested for

prejudice and found no plain error for five reasons:

(1)

the comment was not overly pejorative; (2) it was a small

part of an argument that exceeded three pages in the

record; (3) Appellant did not object; (4) the adjudged

sentence does not reflect any animus on the part of the

judge; and (5) the convening authority significantly

reduced the period of confinement beyond what was required

by the terms of the pretrial agreement.

Id. at 6-7.

Discussion

The certified question asks whether the CCA erred when

it characterized trial counsels statement as merely a

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

gratuitous reference to race as opposed to an argument

based upon racial animus.

However, we believe the parties

have framed a different question in their briefs and

arguments: whether or not unwarranted references to race

during a sentencing argument are subject to prejudice

analysis.

It is improper for trial counsel to seek unduly to

inflame the passions and prejudices of the sentencing

authority.

United States v. Clifton, 15 M.J. 26 (C.M.A.

1983); Rule for Courts-Martial [R.C.M.] 919(b) discussion.

But failure to object to improper argument may constitute

waiver.

R.C.M. 1001(g).

In the absence of an objection,

we review for plain error.

Plain error occurs when there

is (1) error, (2) the error is obvious, and (3) the error

results in material prejudice to a substantial right.

United States v. Powell, 49 M.J. 460, 463-65 (C.A.A.F.

1998).

The Government concedes that the remark had no clear

relationship to any issue in the case and that it could be

misinterpreted as an indirect reference to race.

Although in its brief the Government assumed arguendo that

there might be error, at oral argument it conceded that

trial counsels argument constituted error, whether or not

the statement was gratuitous or based on animus.

The

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

thrust of the Governments argument is that in accordance

with Powell an improper reference to race or ethnicity,

like other improper argument, should be tested for material

prejudice.

In this case, the Government concludes that the

error is not prejudicial because Appellant pleaded guilty

before a court-martial consisting of a judge alone; he

failed to object to the statement; and he received an

appropriate sentence.

In Appellants view, a statement about race is

different from other improper argument.

Where trial

counsel makes improper racial comments the error need not

be tested for prejudice because of the overwhelming

prejudice that that kind of error causes to the military

system of criminal justice.

Further, Appellant invites

our attention to the Army Court of Criminal Appeals

application of United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725 (1993):

that certain errors may affect substantial rights

without a concomitant showing of prejudice.

United States

v. Thompson, 37 M.J. 1023, 1027 (A.C.M.R. 1993).

Relying

on the Army courts holding Appellant asserts that his

substantial and fundamental right to a trial free of the

improper consideration of race is such a right.

Id.

Therefore, Appellant urges that we adopt the Thompson

analytic framework and apply a per se prejudice rule.

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

Appellants argument is attractive for the clarity of

its message.

As this Court has made clear, there is no

room at the bar of military justice for racial bias or

appeals to race or ethnicity.

See, e.g., United States v.

Witham, 47 M.J. 297, 303 (C.A.A.F. 1997)(accused does not

have right to discriminate against prospective members

based on race); United States v. Green, 37 M.J. 380, 384

(C.M.A. 1993)(race is an inappropriate factor for

determining a sentence); United States v. Diffoot, 54 M.J.

149, 154 (C.A.A.F. 2000)(Cox, J., dissenting)(There is no

question that race, ethnicity, or national origin may not

be used to obtain a conviction.); United States v. Greene,

36 M.J. 274, 282 (C.M.A. 1993)(Wiss, J.,

concurring)(Racial discrimination is anathema to the

military justice system.).

We are cognizant that if zero

tolerance means zero tolerance there is a risk that some

may surmise a mixed signal where a court condemns with one

hand but affirms with the other.

The Supreme Court has emphatically condemned

unwarranted racial argument: The Constitution prohibits

racially biased prosecutorial arguments.

McCleskey v.

Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 310 (1987)(citation omitted).

The

majority of the federal circuits test for prejudice in

cases of improper racial argument.

United States v. Doe,

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

903 F.2d 16, 25 (D.C. Cir. 1990); McFarland v. Smith, 611

F.2d 414, 416-17 (2d Cir. 1979); Miller v. North Carolina,

583 F.2d 701, 706-07 (4th Cir. 1978); Smith v. Farley, 59

F.3d 659, 663-64 (7th Cir. 1995); Race v. Pung, 907 F.2d

83, 85 (8th Cir. 1990); Bains v. Cambra, 204 F.3d 964, 974

(9th Cir. 2000); United States v. Abello-Silva, 948 F.2d

1168, 1182 (10th Cir. 1991); accord Diffoot, 54 M.J. 149.

Cognizant of this norm, Appellant argues that the military

should be less tolerant of racial argument than in civilian

practice and apply a per se rule of prejudice.

In our view, unwarranted references to race or

ethnicity have no place in either the military or civilian

forum.

The Supreme Court has not suggested otherwise.

However, we see no reason not to adhere to the prevailing

approach.

See generally Military Rule of Evidence 101

(applying rules of evidence consistent with rules of

evidence in federal district courts).

Our holding

acknowledges the importance of a fair trial and the

insidious impact that racial or ethnic bias, or stereotype,

can have on justice.

At the same time, our holding

acknowledges that where, in fact, there is no prejudice to

an accused, we should not forsake societys other interests

in the timely and efficient administration of justice, the

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

interests of victims, and in the military context, the

potential impact on national security deployment.

Therefore, we agree with the CCA.

Appellant did not

suffer material prejudice to a substantial right.

Trial

counsels statement was before a military judge alone.

Military judges are presumed to know the law and to follow

it absent clear evidence to the contrary.

United States v.

Mason, 45 M.J. 483, 484 (C.A.A.F. 1997)(citation omitted).

Finally, there is no indication in the record that the

statement affected the military judge or impacted

Appellants sentence.

Appellant was convicted of

conspiracy to steal over $1,000 worth of military property,

three specifications of wrongfully disposing of military

property, four specifications of wrongful appropriation of

military property, three specifications of stealing

hundreds of dollars worth of military property, and making

false official statements on two occasions.

Appellants

maximum exposure for these offenses was, among other

punishments, over 54 years of confinement and a

dishonorable discharge.

As noted earlier, Appellants

adjudged sentence included three years of confinement,

total forfeitures, a fine, and a dishonorable discharge.

We caution, however, that such prejudice

determinations are fact specific.

In a given situation

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

racial or ethnic remarks, including before a military

judge, may deny an accused a fair trial.

different.

Race is

See, e.g., McCleskey, 481 U.S. at 309 (Because

of the risk that the factor of race may enter the criminal

justice process, we have engaged in unceasing efforts to

eradicate racial prejudice from our criminal justice

system.)(citing Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 85

(1986)); Smith, 59 F.3d at 665 (Race occupies a special

place in the modern law of constitutional criminal

procedure.); United States v. Lawrence, 47 M.J. 572, 575

(N-M. Ct. Crim. App. 1997)(Absent a logical basis for the

introduction of race as an issue, and strong evidentiary

support for its introduction, race has no place in

military or civilian justice.).

Therefore, it is the rare

case indeed, involving the most tangential allusion, where

the unwarranted reference to race or ethnicity will not be

obvious error.

Our concern with unwarranted statements

about race and ethnicity are magnified when the trial is

before members.

This is true whether or not it is

motivated by animus, as we cannot ultimately know what

effect, if any, such statements may have on the fact finder

or sentencing authority.

10

United States v. Rodriguez, No. 04-5003/MC

Decision

We answer the certified question in the negative.

decision of the United States Navy-Marine Corps Court of

Criminal Appeals is affirmed.

11

The

You might also like

- Collaborative Family School RelationshipsDocument56 pagesCollaborative Family School RelationshipsRaquel Sumay GuillánNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Vce Svce 2017 Notes STUDENT Yr12 Unit 3 English FINALDocument44 pagesVce Svce 2017 Notes STUDENT Yr12 Unit 3 English FINALlngocnguyenNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Quality Control + Quality Assurance + Quality ImprovementDocument34 pagesQuality Control + Quality Assurance + Quality ImprovementMasni-Azian Akiah96% (28)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Simbisa BrandsDocument2 pagesSimbisa BrandsBusiness Daily Zimbabwe100% (1)

- The Neon Red Catalog: DisclaimerDocument28 pagesThe Neon Red Catalog: DisclaimerKarl Punu100% (2)

- CSR Project Report On NGODocument41 pagesCSR Project Report On NGOabhi ambre100% (3)

- MDSAP AU P0002.005 Audit ApproachDocument215 pagesMDSAP AU P0002.005 Audit ApproachKiều PhanNo ratings yet

- Tools - Wood TurningDocument35 pagesTools - Wood TurningThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (2)

- Goldziher - Muslim Studies 2Document190 pagesGoldziher - Muslim Studies 2Christine Carey95% (21)

- United States v. Cossio, A.F.C.C.A. (2015)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Cossio, A.F.C.C.A. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Bennie MacK JR., 4th Cir. (2011)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Bennie MacK JR., 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Briggs, C.A.A.F. (2007)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Briggs, C.A.A.F. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument7 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jack Lee Colson, Delton C. Copeland, 662 F.2d 1389, 11th Cir. (1981)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Jack Lee Colson, Delton C. Copeland, 662 F.2d 1389, 11th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument8 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Alec Brown, JR., 799 F.2d 134, 4th Cir. (1986)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Alec Brown, JR., 799 F.2d 134, 4th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James R. Trim v. R. Michael Cody, Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 72 F.3d 138, 10th Cir. (1995)Document4 pagesJames R. Trim v. R. Michael Cody, Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 72 F.3d 138, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Samuel Douglass Harris and Melba Jean Glass, 441 F.2d 1333, 10th Cir. (1971)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Samuel Douglass Harris and Melba Jean Glass, 441 F.2d 1333, 10th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Smith, 4th Cir. (2002)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Smith, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument9 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Spear, A.F.C.C.A. (2015)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Spear, A.F.C.C.A. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lamb v. OK County Dist Court, 10th Cir. (2007)Document14 pagesLamb v. OK County Dist Court, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dudley D. Morgan, JR., 554 F.2d 31, 2d Cir. (1977)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Dudley D. Morgan, JR., 554 F.2d 31, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Johnny Kibler, 667 F.2d 452, 4th Cir. (1982)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Johnny Kibler, 667 F.2d 452, 4th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Herschel Quinton Nutt v. United States, 335 F.2d 817, 10th Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesHerschel Quinton Nutt v. United States, 335 F.2d 817, 10th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. McDonald, C.A.A.F. (2001)Document23 pagesUnited States v. McDonald, C.A.A.F. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NMCCA 2011 OpinionDocument5 pagesNMCCA 2011 OpinionEhlers AngelaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Elijah Jackson, 344 F.2d 158, 3rd Cir. (1965)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Elijah Jackson, 344 F.2d 158, 3rd Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Armando Restaino, 369 F.2d 544, 3rd Cir. (1966)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Armando Restaino, 369 F.2d 544, 3rd Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hyman Abrams, 427 F.2d 86, 2d Cir. (1970)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Hyman Abrams, 427 F.2d 86, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Riley, C.A.A.F. (2001)Document17 pagesUnited States v. Riley, C.A.A.F. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Pack, C.A.A.F. (2007)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Pack, C.A.A.F. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roy Edward Raines v. United States of America, Michael Pasterchik v. United States, 423 F.2d 526, 4th Cir. (1970)Document12 pagesRoy Edward Raines v. United States of America, Michael Pasterchik v. United States, 423 F.2d 526, 4th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Peter Marines, 535 F.2d 552, 10th Cir. (1976)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Peter Marines, 535 F.2d 552, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Byrd, C.A.A.F. (2004)Document29 pagesUnited States v. Byrd, C.A.A.F. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Cowgill, C.A.A.F. (2010)Document26 pagesUnited States v. Cowgill, C.A.A.F. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Rogers, 10th Cir. (2011)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Rogers, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Miller, 4th Cir. (2003)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Miller, 4th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Carl A. Paullet v. James F. Howard, Supt., State Correctional Inst., PGH., 634 F.2d 117, 3rd Cir. (1980)Document4 pagesCarl A. Paullet v. James F. Howard, Supt., State Correctional Inst., PGH., 634 F.2d 117, 3rd Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Pauling, C.A.A.F. (2004)Document24 pagesUnited States v. Pauling, C.A.A.F. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jimmy Edward Cole, United States of America v. Hubert Winston Craig, 784 F.2d 1225, 4th Cir. (1986)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Jimmy Edward Cole, United States of America v. Hubert Winston Craig, 784 F.2d 1225, 4th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ingham v. Tillery, 10th Cir. (1999)Document7 pagesIngham v. Tillery, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bill of IssuesDocument7 pagesBill of IssuesdebbiNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ciro Michael Caruso, 358 F.2d 184, 2d Cir. (1966)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Ciro Michael Caruso, 358 F.2d 184, 2d Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William H. Warren, Jr. v. Jack Cowley, Warden, 930 F.2d 36, 10th Cir. (1991)Document4 pagesWilliam H. Warren, Jr. v. Jack Cowley, Warden, 930 F.2d 36, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Loving v. United States, C.A.A.F. (2009)Document76 pagesLoving v. United States, C.A.A.F. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Damon Stradwick, United States of America v. Daryl Smith, United States of America v. Personne Elrico McGhee, 46 F.3d 1129, 4th Cir. (1995)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Damon Stradwick, United States of America v. Daryl Smith, United States of America v. Personne Elrico McGhee, 46 F.3d 1129, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Alston, 4th Cir. (2008)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Alston, 4th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Mancil Washington Clark, A/K/A "Mauser,", 541 F.2d 1016, 4th Cir. (1976)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Mancil Washington Clark, A/K/A "Mauser,", 541 F.2d 1016, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James C. Miles v. United States, 385 F.2d 541, 10th Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesJames C. Miles v. United States, 385 F.2d 541, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Stoffer, C.A.A.F. (2000)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Stoffer, C.A.A.F. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Peter S. Dolasco Appeal of Joseph R. Von Atzinger, 470 F.2d 1297, 3rd Cir. (1973)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Peter S. Dolasco Appeal of Joseph R. Von Atzinger, 470 F.2d 1297, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kelvin Moss, 4th Cir. (2011)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kelvin Moss, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Harold Smalls, JR., 4th Cir. (2014)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Harold Smalls, JR., 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. James, 4th Cir. (2001)Document3 pagesUnited States v. James, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. William E. Croom, 998 F.2d 1010, 4th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesUnited States v. William E. Croom, 998 F.2d 1010, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Clay, C.A.A.F. (2007)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Clay, C.A.A.F. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Malcolm Melvin, 4th Cir. (2013)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Malcolm Melvin, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Cary, C.A.A.F. (2006)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Cary, C.A.A.F. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. William N. Anderson, 481 F.2d 685, 4th Cir. (1973)Document21 pagesUnited States v. William N. Anderson, 481 F.2d 685, 4th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gilbert Esco Angle v. Melvin Laird, U.S. Secretary of Defense, 429 F.2d 892, 10th Cir. (1970)Document5 pagesGilbert Esco Angle v. Melvin Laird, U.S. Secretary of Defense, 429 F.2d 892, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Marion Bryant, 5 F.3d 474, 10th Cir. (1993)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Marion Bryant, 5 F.3d 474, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roscoe Thomas Brewer, 427 F.2d 409, 10th Cir. (1970)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Roscoe Thomas Brewer, 427 F.2d 409, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- George Carrigan v. United States, 405 F.2d 1197, 1st Cir. (1969)Document3 pagesGeorge Carrigan v. United States, 405 F.2d 1197, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Washington v. Scott, 10th Cir. (1999)Document5 pagesWashington v. Scott, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Another Federal Indictment of Taos, NM Five Is Coming, Government Says in Court Document (Nov. 14, 2018)Document8 pagesAnother Federal Indictment of Taos, NM Five Is Coming, Government Says in Court Document (Nov. 14, 2018)Matthew VadumNo ratings yet

- Clifford B. Hubbard v. Larry B. Berrong, JR., 7 F.3d 1045, 10th Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesClifford B. Hubbard v. Larry B. Berrong, JR., 7 F.3d 1045, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 11 Sample Papers Accountancy 2020 English Medium Set 3Document10 pages11 Sample Papers Accountancy 2020 English Medium Set 3Joshi DrcpNo ratings yet

- Lecture-1 (General Introduction) Indian Penal CodeDocument12 pagesLecture-1 (General Introduction) Indian Penal CodeShubham PhophaliaNo ratings yet

- Business Idea - Brainstorming TemplateDocument4 pagesBusiness Idea - Brainstorming Templatemanish20150114310No ratings yet

- Love, Desire and Jealousy Through the AgesDocument5 pagesLove, Desire and Jealousy Through the AgesAddieNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Business Schools in The WorldDocument29 pagesTop 10 Business Schools in The WorldLyndakimbizNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and SponsorshipDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and SponsorshipOussemaNo ratings yet

- Famous Entrepreneur Scavenger HuntDocument4 pagesFamous Entrepreneur Scavenger HuntJia GalanNo ratings yet

- All You Need Is LoveDocument2 pagesAll You Need Is LoveSir BülowNo ratings yet

- PRC vs De Guzman: SC reverses CA, nullifies mandamus for physician oathDocument4 pagesPRC vs De Guzman: SC reverses CA, nullifies mandamus for physician oathJude FanilaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Period GerphisDocument4 pagesJapanese Period GerphisCharles Ronel PataludNo ratings yet

- Informal GroupsDocument10 pagesInformal GroupsAtashi AtashiNo ratings yet

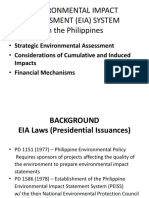

- Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesthekeypadNo ratings yet

- Big Data Executive Survey 2018 Findings PDFDocument18 pagesBig Data Executive Survey 2018 Findings PDFSaraí OletaNo ratings yet

- KenEi Mabuni Sobre ReiDocument6 pagesKenEi Mabuni Sobre ReirfercidNo ratings yet

- Arshiya Anand Period 5 DBQDocument3 pagesArshiya Anand Period 5 DBQBlank PersonNo ratings yet

- 3CO02 Assessment Guidance 2022Document5 pages3CO02 Assessment Guidance 2022Gabriel ANo ratings yet

- Juris PDFDocument4 pagesJuris PDFSister RislyNo ratings yet

- UK Health Forum Interaction 18Document150 pagesUK Health Forum Interaction 18paralelepipicoipiNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Looking at OthersDocument25 pagesUnit 2 Looking at OthersTipa JacoNo ratings yet

- Christopher Brown and Matthew Mahrer IndictmentDocument8 pagesChristopher Brown and Matthew Mahrer IndictmentCBSNewYork ScribdNo ratings yet

- WHO TRS 999 Corrigenda Web PDFDocument292 pagesWHO TRS 999 Corrigenda Web PDFbhuna thammisettyNo ratings yet