Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States v. Martinez-Melgar, 591 F.3d 733, 4th Cir. (2010)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States v. Martinez-Melgar, 591 F.3d 733, 4th Cir. (2010)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

ANTONIO ALFREDO MARTINEZMELGAR, a/k/a Alfredo Antonio

Martinez-Melgar,

Defendant-Appellant.

No. 08-4569

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina, at Charlotte.

Frank D. Whitney, District Judge.

(3:06-cr-00449-FDW-1)

Argued: December 4, 2009

Decided: January 20, 2010

Before SHEDD and DUNCAN, Circuit Judges,

and T. S. ELLIS, III, Senior United States District Judge

for the Eastern District of Virginia, sitting by designation.

Vacated and remanded by published opinion. Senior Judge

Ellis wrote the opinion, in which Judge Shedd and Judge

Duncan joined.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Ann Loraine Hester, FEDERAL DEFENDERS

OF WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA, INC., Charlotte, North

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

Carolina, for Appellant. Mark Andrew Jones, OFFICE OF

THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Charlotte, North Carolina, for Appellee. ON BRIEF: Claire J. Rauscher, Executive Director, Cecilia Oseguera, FEDERAL DEFENDERS OF

WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA, INC., Charlotte, North

Carolina, for Appellant. Gretchen C. F. Shappert, United

States Attorney, Charlotte, North Carolina, for Appellee.

OPINION

ELLIS, Senior District Judge:

Appellant, convicted on charges of drug trafficking and

possession of a firearm during and in relation to the drug trafficking conviction, challenges his sentence as procedurally

infirm. He claims the district court erroneously counted disposition by a state drug court supervision program as a "prior

sentence" within the meaning of U.S.S.G. 4A1.1 and

4A1.2. We agree, and therefore vacate the sentence and

remand for resentencing.

I.

On May 11, 2007, Martinez-Melgar pled guilty without a

plea agreement to (i) one count of possession with intent to

distribute cocaine in violation of 21 U.S.C. 841(a), and (ii)

one count of possession of a firearm during and in relation to

a drug trafficking crime in violation of 18 U.S.C. 924(c).

The offense conduct charged in the indictment, and admitted

to by Martinez-Melgar, occurred on February 2, 2006. J.A. 9,

46. A probation officer subsequently prepared a presentence

report outlining (i) the offenses, (ii) Martinez-Melgars criminal history, (iii) his personal characteristics, and (iv) available

sentencing options. With respect to Martinez-Melgars criminal history, the report states that in connection with a 2003

cocaine possession charge in North Carolina state court,

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

Martinez-Melgar on January 13, 2004 "was ordered to participate in and successfully complete the District Court Step

Drug Program as outlined in the Deferred Prosecution Agreement." J.A. 56. According to the presentence report,

Martinez-Melgar was thereafter "[t]ransferred to unsupervised

probation" on November 23, 2004, and the charge was ultimately dismissed on May 9, 2006. J.A. 5. Accordingly, the

probation officer applied a one-point "prior sentence"

enhancement to Martinez-Melgars offense level for his participation in the program because "an admission of guilt in a

judicial proceeding is required for acceptance into this program in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina." J.A. 6. Moreover, the probation officer assessed two additional criminal

history points because "[a]t the time the instant offense was

committed, the defendant was a participant in the District

Court Step Drug Program" and was therefore on probation as

that term is used in the Sentencing Guidelines. J.A. 6.

Martinez-Melgar, through counsel, objected to the probation

officers assessment of these three criminal history points.

Specifically, Martinez-Melgar objected to the findings (i) that

he made an admission of guilt in connection with his participation in "STEP," the Mecklenburg County, North Carolina

drug court supervision program, and (ii) that he was on probation at the time of the offense of conviction.

Martinez-Melgar raised these objections during the course

of a sentencing hearing held on April 14, 2008. His counsel

represented that she was unable to locate any records relating

to the charge in North Carolina state court, or to his alleged

participation in the STEP program. In response, the probation

officer indicated that computerized printouts obtained from a

state agency demonstrated that Martinez-Melgar had, in fact,

entered and successfully completed the STEP program. To

support her statement that participation in the STEP program

required an admission of guilt, the probation officer also

described her experience working in the states "general

deferred prosecution program." J.A. 59. In that program, the

officer explained, "the defendant was required to sign a state-

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

ment admitting their [sic] guilt to the offense." J.A. 58. She

further noted that in the states general deferred prosecution

program at the time she was a state probation officer, the

statement of responsibility would be "handed to the judge,

along with the Deferred Prosecution Agreement, for review,"

and that the judge would sign the contract and the statement

of responsibility would be retained in the defendants probation file. J.A. 58. While acknowledging that the STEP program was "slightly different," the probation officer stated that

she had spoken with a Mecklenburg County assistant district

attorney named Steve Ward, who

assured me that at the time the program was initiated

and presently, a statement of guiltan admission of

guilt was necessary for acceptance into the program,

and he has no reason to believe that at any time in

between the beginning of the program and now that

that policy would have changed.

J.A. 59.

Nonetheless, the probation officer indicated that she had

been unable to acquire the statement of responsibility or

deferred prosecution agreement because the states probation

office could not locate Martinez-Melgars probation file and

because the public defenders office refused to allow her to

view their file. The district judge expressed some frustration

with the public defenders apparent refusal to turn over "the

documents,"1 noting that they were not privileged or confidential because "it was done in open court by a state district

judge." J.A. 63. Thus, the district judge continued sentencing

to May 12, 2008, in part to afford the government an adequate

opportunity to locate documents related to Martinez-Melgars

participation in the STEP program.

1

While there is some ambiguity as to which "documents" the district

judge was referring to, it appears from the record that he was alluding to

the deferred prosecution agreement and statement of responsibility previously referenced by the probation officer.

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

At the May 12, 2008 hearing, the governments counsel

informed the district judge that he had been unable to locate

any such documents. He further stated that the public defenders file had revealed that Martinez-Melgar was represented

by private counsel at the time that he allegedly entered the

STEP program, and the governments counsel apparently

decided not to contact this attorney to attempt to retrieve copies of the statement of responsibility and the deferred prosecution agreement. Instead, at the May 12, 2008 hearing, the

government presented testimony from Steve Ward, the Mecklenburg County assistant district attorney. Ward testified that

he was the "architect" of Mecklenburg Countys STEP program, that he was its coordinator from 1994 until 1998, and

that at the time of the hearing he sat on the management committee that oversees the program. Accordingly, while he had

no personal knowledge whatever of Martinez-Melgars case

or his alleged participation in the STEP program, Ward testified to the structure and procedures of the STEP program as

he understood them. Specifically, Ward described STEP as a

"pretrial diversion program." J.A. 84. With respect to the

requirements to enter the program, Ward testified as follows:

[An eligible defendant must] sign a contract with

the court that is signed by the district court judge,

the prosecutor, defense counsel, and the defendant

agreeing to abide by all the terms and conditions

of the program. And they are also required to sign

a Statement of Responsibility, or an admission of

guilt, where they admit that they possessed the

drugs in question.

Q: And what is donethe Statement of Responsibility, what is done with that document?

A: The Statement of Responsibility is usually

retained by the defense attorney pending the outcome of the case. It is not filed in the court file, nor

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

is it kept by the prosecutor. The contract is put in the

court file and a copy is given to all parties.

J.A. 86-87. Ward further explained that upon signing the contract and the statement of responsibility, the defendant enters

the STEP program, which entails attending meetings, receiving counseling, and appearing in court every two weeks to

report on compliance or noncompliance with the programs

rules. According to Ward, if a defendant fails to comply with

the program terms, he is removed from the program and

defense counsel is ordered to turn the statement of responsibility over to the prosecutor for use in prosecuting the defendant. On the other hand, if a defendant successfully completes

the program, then the "charges would be dismissed and the

documentation [would remain] . . . where it has been all

along." J.A. 87. Finally, Ward noted that "[a]ll of this is contingent on everyone doing what they are supposed to do, and

there may be a circumstance, a rare one, where someone forgets to get the Statement of Responsibility signed." J.A. 87.

Following Wards testimony, Martinez-Melgars attorney

argued that the government had failed to show (i) that

Martinez-Melgar participated in the STEP program or (ii) that

he made an admission of guilt. The attorney further objected

to the use of computerized printouts from the North Carolina

Offender Information System as evidence of MartinezMelgars cocaine possession charge and his subsequent participation in the STEP program.

The district judge overruled these objections and concluded

that the one-point criminal history enhancement was appropriate. In support of his ruling, the district judge found that the

computerized printouts proved (i) that Martinez-Melgar was

charged in North Carolina state court with possession of

cocaine, (ii) that he entered the STEP program on January 13,

2004 as a result of this charge, (iii) that he was transferred to

unsupervised probation on November 23, 2004, and (iv) that

the charge of cocaine possession was ultimately dismissed on

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

May 9, 2006. J.A. 97-98. Moreover, the district judge found

that Wards testimony showed that, in order to enter the STEP

program, Martinez-Melgar must have signed a statement of

responsibility, which, he held, constituted an admission of

guilt. The district judge did not explicitly rule on the objection

relating to whether Martinez-Melgar was on probation at the

time of the offense conduct. Instead, he calculated a guidelines sentencing range that included one criminal history point

attributable to the prior sentence and two criminal history

points attributable to committing the offense while under a

criminal justice sentence. When the district judge asked if the

parties agreed to the calculation, Martinez-Melgars counsel

said that she did, "subject to my objections." J.A. 98. Yet, at

no point during the course of the May 12, 2008 hearing was

the objection to the finding that Martinez-Melgar was on probation at the time of the offense conduct specifically raised,

nor was any objection raised with respect to any failure by the

district judge to make a factual finding to that effect. The district judge proceeded to calculate an offense level of 22, a

criminal history category of II, and a guideline sentencing

range of 46 to 57 months on the first count and 60 months on

the second count, which was statutorily required to run consecutively to the sentence imposed on the first count. Accordingly, he sentenced Martinez-Melgar to a total of 117 months

in prison.

II.

The issue on appeal is whether the district court properly

assessed three criminal history points in connection with

Martinez-Melgars alleged participation in the STEP program.

Martinez-Melgar argues that the sentencing court erred in

assessing the three criminal history points pursuant to

U.S.S.G. 4A1.1(c) and 4A1.1(d) because his participation

in the program did not result from an admission of guilt in a

judicial proceeding in open court, as required by the guidelines. In the alternative, he contends that the sentencing court

erred in assessing two of those three criminal history points

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

pursuant to 4A1.1(d) because he was no longer under a

criminal justice sentence at the time of the offense of conviction. Pure questions of law related to guidelines determinations are reviewed de novo, while factual findings at

sentencing are reviewed for clear error. See United States v.

Dove, 247 F.3d 152, 155 (4th Cir. 2001); see also United

States v. Moreland, 437 F.3d 424, 433 (4th Cir. 2006) (applying the same standard post-Booker).

The analysis properly begins with the Sentencing Guidelines provisions governing criminal history, which require

assessing one criminal history point for a "prior sentence,"

U.S.S.G. 4A1.1(c), and two additional points if the offense

of conviction is committed "while under any criminal justice

sentence, including probation, parole, supervised release,

imprisonment, work release, or escape status," Id. 4A1.1(d).

The terms "prior sentence" and "criminal justice sentence" are

defined to include "any sentence previously imposed upon

adjudication of guilt, whether by guilty plea, trial, or plea of

nolo contendere, for conduct not part of the instant offense."2

Id. 4A1.2(a)(1). The guidelines further clarify that

"[d]iversion from the judicial process without a finding of

guilt (e.g., deferred prosecution) is not counted," but that a

"diversionary disposition resulting from a finding or admission of guilt, or a plea of nolo contendere, in a judicial proceeding is counted" as a sentence even if a conviction is not

formally entered. Id. 4A1.2(f). Importantly, the commentary

to 4A1.2 further states that a diversionary disposition qualifies as a "prior sentence" only if it results from "a judicial

determination of guilt or an admission of guilt in open court."

Id. 4A1.2 cmt. 9. Thus, in order to qualify as a prior sentence and as a criminal justice sentence within the meaning of

4A1.1(c) and 4A1.1(d), the sentence must result from (i)

2

"Criminal justice sentence" is defined as a subset of a "prior sentence,"

namely, as a prior sentence having a custodial or supervisory component.

Thus, a term of probation would normally qualify as a "criminal justice

sentence" and as a "prior sentence." See U.S.S.G. 4A1.1 cmt. 4.

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

a finding or an admission of guilt (ii) in a judicial proceeding

(iii) in open court.

Martinez-Melgar first argues that the district court erred as

a matter of law in two respects. First, he argues that a qualifying prior sentence requires formal entry of a plea or of a judgment of conviction. This argument is without merit. Indeed,

the guidelines plainly include within the definition of a prior

sentence diversionary dispositions resulting from an "admission of guilt in open court." Id. 4A1.2 cmt. 9. MartinezMelgars construction of 4A1.2 would impermissibly read

this language out of the guidelines. Therefore, such an interpretation is contrary to the plain meaning of 4A1.2.3

Second, Martinez-Melgar argues that the district judge did

not make the required factual finding that the alleged admission occurred in a judicial proceeding in open court. Yet, it is

clear from the record that the district judge made precisely

such a finding. Indeed, during the April 14, 2008 hearing, the

district judge repeatedly referred to the "documents," including the statement of responsibility and the deferred prosecution agreement, as having been "put on the record in open

court." J.A. 63; see also J.A. 61, 64. Thus, having determined

that the district court did make the requisite factual finding,

we next turn to the question whether that finding was clearly

erroneous.

It is well-settled that in reviewing a district courts factual

findings for clear error, the court of appeals does not simply

substitute its judgment for that of the district court. Instead, a

factual determination may be found to be clearly erroneous

only "when although there is evidence to support [the district

3

See United States v. Jones, 448 F.3d 958, 960-61 (7th Cir. 2006) (concluding that a stipulation to "the facts supporting the charge" resulting in

a disposition of supervision was sufficient to constitute a prior sentence

under 4A1.2, even in the absence of a formal plea or judgment of conviction).

10

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

courts finding], the reviewing court on the entire evidence is

left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has

been committed." United States v. U.S. Gypsum Co., 333 U.S.

364, 395 (1948). And in this respect, a reviewing court may

only find clear error where the factual determinations "are

not supported by substantial evidence." Brice v. Va. Beach

Corr. Ctr., 58 F.3d 101, 106 (4th Cir. 1995) (quoting U.S.

Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. at 361). Put another way, clear error

occurs when a district courts factual findings "are against the

clear weight of the evidence considered as a whole." Miller v.

Mercy Hosp., Inc., 720 F.2d 356, 361 (4th Cir. 1983).

Because the district courts determination, by a preponderance

of the evidence, that Martinez-Melgar admitted his guilt in a

judicial proceeding in open court is unsupported by the

record, we hold that this finding was clearly erroneous.

To begin with, it is clear that district courts may properly

rely on circumstantial evidence in the course of making factual findings for purposes of calculating the correct advisory

guidelines range. In other words, there is no rule that a transcript, signed statement, or eyewitness testimony need be

presented in order for a sentencing court to conclude that the

defendant admitted his guilt in a judicial proceeding in open

court. More specifically, if evidence is presented that a defendant previously participated in a specific diversionary program, and if there is further evidence presented that the

specific program requires an admission of guilt in a judicial

proceeding in open court as a prerequisite to entry, then, in

the absence of any evidence to the contrary, a sentencing

court could reasonably conclude, by a preponderance of the

evidence, that the defendant admitted his guilt in a judicial

proceeding in open court. In such an event, a court must

assess the additional criminal history point accordingly. Yet,

as always, the inferences drawn from evidence by the trier of

fact must be reasonable in light of the record taken as a

whole. Bouchat v. Baltimore Ravens, Inc., 241 F.3d 350, 35960 (4th Cir. 2001).

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

11

The district judge in this case properly relied on computerized printouts from the North Carolina Offender Information

System to support his findings (i) that Martinez-Melgar was

charged with cocaine possession and (ii) that as a result he

enrolled in, and successfully completed, the Mecklenburg

County STEP program. The district judge committed no error

in reaching these conclusions. Indeed, sentencing courts routinely rely on similar printouts of computerized records in

making such findings for purposes of calculating guidelines

ranges, and there is no support in our case law for MartinezMelgars contention that courts may not rely on such records

in these circumstances. Specifically, Martinez-Melgars argument that the district court erred in considering evidence other

than what is permitted by Taylor v. United States, 495 U.S.

575, 602 (1990), and Shepard v. United States, 544 U.S. 13,

16 (2005), misapprehends the significance of those opinions.

Those cases concerned whether the substantive content of a

prior conviction qualified the defendant for an Armed Career

Criminal Act enhancement pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 924(e),

not the conceptually distinct issue of whether a conviction had

occurred at all. Similarly, in United States v. Maroquin-Bran,

___ F.3d ____, 2009 WL 3720864, at *3 (4th Cir. Nov. 9,

2009), we held that the district court could only consider

"Shepard-approved documents" for purposes of determining

whether the defendants prior conviction constituted a "drug

trafficking offense" that qualified him for a guidelines

enhancement. Again, the issue in Maroquin-Bran, as in Taylor and Shepard, was not whether the prior conviction had

occurred, but rather the issue was the nature of the prior

offense. To the contrary, in this case the substantive content

of Martinez-Melgars alleged admission is not in issue;

instead, the question is whether the district judge clearly erred

in concluding that Martinez-Melgar made an admission in

open court in a judicial proceeding. Thus, in a case where, as

here, there is no indication whatever that the state records are

inaccurate, sentencing judges may reasonably conclude that

the records are accurate for purposes of guidelines calculations.

12

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

In concluding that Martinez-Melgar admitted his guilt in a

judicial proceeding in open court, the district judge relied on

statements of a federal probation officer and the testimony of

Steve Ward, the Mecklenburg County assistant district attorney. While the conclusion that Martinez-Melgar admitted his

guilt is supported by the probation officers assertions and

Wards testimony, neither statement supports the conclusion

that he was required to do so, and in fact did so, in a judicial

proceeding in open court. Specifically, the probation officers

statements about deferred prosecution program procedures

referred not to the Mecklenburg County STEP program, but

instead to North Carolinas "general deferred prosecution program," with which she was familiar from having been a North

Carolina state probation officer at some time in the past. J.A.

59. Thus, the probation officers assertion that, in the states

"general deferred prosecution program," a "statement admitting [a defendants] guilt to the offense . . . was handed to the

judge, along with the Deferred Prosecution Agreement, for

review" is only probative of the Mecklenburg County STEP

program procedures to the extent that the record allows an

inference that the same procedure was followed in both programs. J.A. 58.

Yet, the record refutes such an inference. Indeed, it is pellucidly clear from the record that the STEP program procedures

differ from the general state deferred prosecution program

procedures in a manner that does not permit the inference that

defendants are required to admit their guilt in a judicial proceeding in open court in order to be enrolled in the STEP program. While the probation officer stated that under the general

North Carolina deferred prosecution program, the statements

of responsibility are retained in the defendants probation file,

she also said that Ward informed her that under the STEP program, a deliberate choice was made not to keep the statements

of responsibility in the probation file because "they didnt

want the admission of guilt floating around in all these different files." J.A. 59. Moreover, in his testimony, Ward distinguished between (i) the STEP program contract, which is

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

13

signed by the judge, prosecutor, defense counsel, and the

defendant, and placed in the court file, and (ii) the statement

of responsibility, which is "usually retained by the defense

attorney pending the outcome of the case, . . . [and] is not

filed in the court file, nor is it kept by the prosecutor." J.A.

8687. Finally, Ward stated that upon successful completion

of the program, the charges would be dismissed and "the documentation [would remain] . . . where it has been all along."

J.A. 87. Only if the defendant is removed from the program

prior to successful completion will defense counsel turn over

the statement of responsibility to the prosecutor who, presumably, would file it in court.

Wards testimony therefore made it clear that the STEP

program does not follow the same procedures as the general

North Carolina deferred prosecution program with respect to

statements of responsibility. Moreover, it is clear that in creating the STEP program, measures were implemented to

address concerns that a successful STEP program participants statement of responsibility would still be "floating

around" after the charges were dismissed. Thus, the probation

officers statement regarding the general North Carolina program procedures are not probative of the STEP program procedures that may have been followed in Martinez-Melgars

case. Indeed, to the extent that any inference may be drawn

from Wards testimony concerning whether defendants

admission of guilt required for participation in the STEP program ordinarily occurs in a judicial proceeding in open court,

the only permissible inference is that it does not.4 Accordingly, the district judge clearly erred in concluding, on the

4

The inference that the STEP program does not require an admission of

guilt in a judicial proceeding in open court is further supported by the

North Carolina probation statute, which only requires "approval of the

court, pursuant to a written agreement with the defendant" for placement

of a defendant on probation in connection with enrollment in a drug court

treatment program. N.C. Gen. Stat. 15A-1341(a2). The statute does not

require a defendant to admit guilt to participate in a drug court treatment

program. Id.

14

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

basis of the record before him, that Martinez-Melgars admission of guilt occurred in a judicial proceeding in open court.

It follows that the criminal history points should not have

been assessed.

Martinez-Melgar also objects to the guidelines range calculation on the ground that the district judge failed to make a

required factual finding that he was on probation at the time

of the offense of conviction, February 2, 2006. Because the

error addressed above requires that the sentence be vacated,

this issue need not be decided at this time. Nonetheless, for

purposes of offering appropriate guidance to the district court

on remand, it is worth noting that, while it appears that the

district judge found that Martinez-Melgar was still on probation when the offense conduct occurred,5 the record does not

support this conclusion. This is particularly true because the

North Carolina probation statute limits deferred prosecution

probation periods to a maximum of two years, a time period

that had expired on or before January 13, 2006, well before

the offense of conviction occurred on February 2, 2006. See

N.C. Gen. Stat. 15A-1342(a). Thus even if, on remand, the

government is able to prove that Martinez-Melgars participation in the STEP program resulted from an admission of guilt

in a judicial proceeding in open court, it is far from clear that

it can be shown that Martinez-Melgar was still on probation

from the STEP program at the time of the offense of conviction.

5

Specifically, the district judge found that Martinez-Melgar entered the

STEP program on January 13, 2004, "and ultimately on November 23,

2004, was transferred to unsupervised probation, and on May 9th, 2006,

the charge of possession of cocaine, which is the key charge were talking

about in paragraph 23 of the Presentence Report, was dismissed." J.A. 97.

The obvious inference from this statement is that the district judge found

that Martinez-Melgar was on unsupervised probation until May 9, 2006,

the date on which the charge was dismissed.

UNITED STATES v. MARTINEZ-MELGAR

15

III.

For the foregoing reasons, we vacate Martinez-Melgars

sentence and remand to the district court for resentencing consistent with this opinion.

VACATED AND REMANDED

You might also like

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Handbook of Information 2009 - 2Document68 pagesHandbook of Information 2009 - 2Shivu HcNo ratings yet

- Notice of Appeal 153554 2017 NYSCEF Cert PDFDocument200 pagesNotice of Appeal 153554 2017 NYSCEF Cert PDFAnonymous 5FAKCTNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Protection in Europe CCosDocument6 pagesHuman Rights Protection in Europe CCosTanisa MihaiļenkoNo ratings yet

- Romualdez Vs MarceloDocument2 pagesRomualdez Vs MarceloVanessa C. RoaNo ratings yet

- Southeast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp vs. Balite Portal MiningDocument2 pagesSoutheast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp vs. Balite Portal MiningRob3rtJohnson100% (2)

- Accomplice-Concept of the term less than 40 charactersDocument25 pagesAccomplice-Concept of the term less than 40 charactersharsh vardhanNo ratings yet

- Video # 10Document5 pagesVideo # 10JORGE LUIS HINCAPIE GARCIANo ratings yet

- People Vs de CastroDocument5 pagesPeople Vs de CastroMark Lester Lee AureNo ratings yet

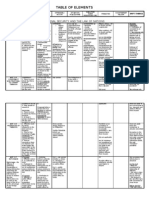

- CRIM2 Table of ElementsDocument40 pagesCRIM2 Table of Elementssaintkarri100% (9)

- G.R. No. 175433 March 11, 2015 ATTY. JACINTO C. GONZALES, Petitioner, vs. MAILA CLEMEN F. SERRANO, Respondent. Decision Peralta, J.Document8 pagesG.R. No. 175433 March 11, 2015 ATTY. JACINTO C. GONZALES, Petitioner, vs. MAILA CLEMEN F. SERRANO, Respondent. Decision Peralta, J.Vina LangidenNo ratings yet

- Detailed Teaching Syllabus (DTS) and Instructors Guide (Ig'S)Document13 pagesDetailed Teaching Syllabus (DTS) and Instructors Guide (Ig'S)raul gironellaNo ratings yet

- Governance As Theory: Five Propositions : Gerry StokerDocument10 pagesGovernance As Theory: Five Propositions : Gerry StokerrullyNo ratings yet

- California National Merit SemifinalistsDocument11 pagesCalifornia National Merit SemifinalistsBayAreaNewsGroup100% (2)

- New Media - Section 7 - Social Media Analytics CompassDocument12 pagesNew Media - Section 7 - Social Media Analytics CompassAhmed SamehNo ratings yet

- LL.B. I Semester (Annual) Examination, June, 2021.: Subject: Jurisprudence-I Paper Code: LB-101Document2 pagesLL.B. I Semester (Annual) Examination, June, 2021.: Subject: Jurisprudence-I Paper Code: LB-101Mansoor AhmedNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument1 pageLaurel Vs GarciacyhaaangelaaaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Constitution of Different CountriesDocument14 pagesComparative Constitution of Different CountriesPranay JoshiNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 MagilDocument12 pagesAssessment 1 MagilAlessandro FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds unregistered land sale over subsequent registered execution saleDocument3 pagesSupreme Court upholds unregistered land sale over subsequent registered execution saleJoseLuisBunaganGuatelaraNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 Public Goods, Public Choice and Government FailuresDocument22 pagesTutorial 4 Public Goods, Public Choice and Government FailuresLoo Bee YeokNo ratings yet

- AGGRAVATINGDocument38 pagesAGGRAVATINGRegine LangrioNo ratings yet

- JRN 101 Full Semester PackageDocument19 pagesJRN 101 Full Semester PackageNerdy Notes Inc.No ratings yet

- Note On AdvertisementsDocument4 pagesNote On AdvertisementsMuncipal Engineer EluruNo ratings yet

- John Livingston Nevius - A Historical Study of His Life and Mission MethodsDocument398 pagesJohn Livingston Nevius - A Historical Study of His Life and Mission MethodsGladston CunhaNo ratings yet

- Mulhern 2009Document18 pagesMulhern 2009Elizabeth Aguilar AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Piracy in General, and Mutiny On The High Seas or Philippine Waters People V. TulinDocument2 pagesPiracy in General, and Mutiny On The High Seas or Philippine Waters People V. TulinadeeNo ratings yet

- Kedudukan Hukum Hipotek Kapal Laut Dalam Hukum Jaminan Dan Penetapan Hipotek Kapal Laut Sebagai Jaminan Perikatan Syukri Hidayatullah, S.H., M.HDocument7 pagesKedudukan Hukum Hipotek Kapal Laut Dalam Hukum Jaminan Dan Penetapan Hipotek Kapal Laut Sebagai Jaminan Perikatan Syukri Hidayatullah, S.H., M.HDani PraswanaNo ratings yet

- Starbucks SWOT analysisDocument22 pagesStarbucks SWOT analysisPratik PatilNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3634903 PDFDocument7 pagesSSRN Id3634903 PDFMikaela PamatmatNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 259 4232Document60 pages10 1 1 259 4232Anonymous CzfOUjdNo ratings yet