Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Volvo Trucks v. United States, 4th Cir. (2004)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Volvo Trucks v. United States, 4th Cir. (2004)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA,

INCORPORATED, formerly known as

Volvo GM Heavy Truck

Corporation,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

No. 03-1256

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of North Carolina, at Durham.

Frank W. Bullock, Jr., District Judge.

(CA-01-416-3)

Argued: February 24, 2004

Decided: May 5, 2004

Before WILKINSON, NIEMEYER, and DUNCAN, Circuit Judges.

Affirmed by published opinion. Judge Niemeyer wrote the opinion,

in which Judge Wilkinson and Judge Duncan joined.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Tamura D. Coffey, WILSON & ISEMAN, WinstonSalem, North Carolina, for Appellant. Randolph L. Hutter, Tax Division, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Washington,

D.C., for Appellee. ON BRIEF: G. Gray Wilson, J. Chad Bomar,

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

WILSON & ISEMAN, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for Appellant. Eileen J. OConnor, Assistant Attorney General, Richard Farber,

Tax Division, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE,

Washington, D.C., for Appellee.

OPINION

NIEMEYER, Circuit Judge:

Volvo Trucks of North America, Inc. commenced this action

against the Internal Revenue Service ("IRS") to obtain an $856,226

refund of federal excise taxes paid under 26 U.S.C. 4051(a) for

heavy trucks that Volvo sold to its dealers during the 1989-91 period.

Volvo claimed to be entitled to an exemption from the tax, but the

IRS disallowed the exemption because Volvo failed to support its

claim with the documentation required by Temporary Treasury Regulation 145.4052-1 (1988).

Volvo contends (1) that Regulation 145.4052-1 was an arbitrary

and capricious regulation as promulgated and as applied; (2) that

Volvo substantially complied with the regulations requirements; and

(3) that Volvos noncompliance with the regulation was attributable

to representations made by IRS agents and therefore that the IRS

should be equitably estopped from disputing Volvos refund request.

The district court dismissed Volvos equitable estoppel claim under

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), and it granted the IRSs

motion for summary judgment on the other two claims. For the reasons that follow, we affirm.

I

Before 1983, the Internal Revenue Code imposed an excise tax on

the first sale by a manufacturer or importer of heavy-duty trucks, but

in 1983, Congress changed the law to impose the 12% tax on the

value of the "first retail sale" of such trucks. 26 U.S.C. 4051, 4052

(1983). Congress defined the "first retail sale" as "the first sale . . .

for a purpose other than for resale or leasing in a long-term lease." Id.

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

4052(a)(1). Under this scheme, manufacturers and importers would

be exempt from excise tax on trucks sold to their dealers for resale,

and their dealers would pay the tax. For trucks that the dealers purchased for their own use, however, the manufacturer or the importer

would have to pay the tax. Temporary Treasury Regulation

145.4052-1 was promulgated in 1988 to provide the mechanism by

which the IRS collected this tax.

Section 4052 authorized the IRS to promulgate regulations, directing the IRS to prescribe rules "similar to the rules of . . . section

4222." 26 U.S.C. 4052(d) (later amended by Pub. L. No. 105.34,

1434(b)(1) (1997)). Under 4222, which governs a different set of

tax exemptions, taxpayers are required to register with the IRS before

they can be eligible for the exemptions. Id. 4222(a). In addition to

the registration requirement, parties to sales governed by 4222 must,

as required by regulations promulgated under 4222, also provide the

IRS with a written statement establishing the nontaxable nature of

each sale. 26 C.F.R. 48.4222(a)(1)(c), 48.4221-1(c). Acting on

4052s instruction to use 4222 as a guide in establishing regulations for 4052, the IRS promulgated Temporary Treasury Regulation 26 C.F.R. 145.4052-1 (1988).

Regulation 145.4052-1(a) provided that in order for a

manufacturer-seller to be exempt from the excise tax imposed under

4051, both the manufacturer-seller and the dealer-purchaser had to

be registered with the IRS. In addition, the manufacturer-seller must

have obtained from the dealer-purchaser a signed certificate that

included the dealers registration number and indicated that the transaction was for resale or long-term lease.

Volvo Trucks of North America, Inc. ("Volvo"), a manufacturer of

heavy trucks and truck parts, responded to this regulation by instructing each of its franchised dealers to register with the IRS and to provide Volvo with exemption certificates that indicated the dealers

registration number and that listed the trucks purchased for resale.

Two such dealers, Atlas Engine Rebuilders, Inc. ("Atlas") and Alaska

Sales and Service, Inc. ("Alaska"), sent Volvo certificates with the

phrase "Applied For" in the field reserved for its IRS registration

number, indicating that they had applied for but not yet received a

registration number for the relevant period. Another dealer, Alameda

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

Truck Center, Inc. ("Alameda"), never supplied Volvo with a certificate. There is evidence that despite their failure to produce the certificates to Volvo, Alaska and Alameda had in fact registered with the

IRS.

In 1991, the IRS began two excise tax audits of Volvo, one covering the period 1989-90 and the second covering 1990-91. At the end

of the audits, the IRS assessed Volvo with over $2.1 million in excise

taxes and penalties to cover those sales transactions that it had with

dealers for which Volvo had not produced completed dealer certifications. Volvo paid the assessed amount and pursued administrative

appeals. During this administrative process, the IRS refunded taxes to

Volvo for transactions where the IRS could confirm that the dealer

had paid the excise tax, even if the dealer had not properly registered

and had not properly certified the transaction. As a result of this process, Volvos liability for excise taxes was reduced from over $2.1

million to $856,226.08. Volvo commenced this action seeking a

refund of this remaining amount.

In its complaint, Volvo contends (1) that Temporary Treasury Regulation 145.4052-1 was invalid because it was an arbitrary and

capricious regulation; (2) that Volvo substantially complied with Regulation 145.4052-1; and (3) that the IRS should in any event be

equitably estopped from enforcing the regulation because, during the

administrative process, IRS made representations on which Volvo

relied in failing to produce the required documentation. With respect

to the equitable estoppel claim, Volvo alleged that IRS agents told

Volvo that it did not need to have exemption certificates, but the IRS

later changed its position; that IRS agents told Volvo that exemption

certificates would apply retroactively but then denied their retroactive

effect; and that IRS agents told Volvo that the IRS would accept affidavits in lieu of certifications but then refused to accept affidavits.

The district court granted the IRSs motion for summary judgment

on Volvos first two claims relating to Regulation 145.4052-1 and

Volvos compliance with it, and it granted the IRSs motion to dismiss the third claim relating to equitable estoppel on the ground that

Volvo failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. This

appeal followed.

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

II

Volvo contends first that the promulgation of Temporary Treasury

Regulation 145.4052-1 was an invalid exercise of the IRSs rulemaking authority. More particularly, Volvo argues that (1) Regulation

145.4052-1 was inconsistent with 26 U.S.C. 4052, which authorized the regulation; (2) the regulation was inconsistent with congressional intent; (3) the IRS failed to consider the possibility of doubletaxation in promulgating the regulation; and (4) the regulation was not

"uniformly or literally applied" in all circumstances. We address these

arguments seriatum.

On Volvos first argument that the regulation was inconsistent with

the statute, we conclude that the regulation was not only consistent

with the plain language of the statute, but it was explicitly contemplated by the statute. In 4052, Congress authorized the IRS to promulgate regulations "similar to the rules of . . . section 4222." 26

U.S.C. 4052(d)(2). Section 4222 requires that all parties to a sale be

registered with the IRS as a condition to receiving the tax exemptions

that are detailed in 4221. In addition, the regulations promulgated

under 4221 and 4222 require that purchasers provide sellers with

written statements that include their IRS registration numbers and the

nontaxable purpose for which the items were purchased. 26 C.F.R.

48.4222(a)-(1)(c), 48.4221-1(c). Thus, when Congress specifically

instructed the IRS in 4052 to promulgate regulations similar to

those in 4222, it directed the Commissioner to impose registration

and certification requirements in connection with sales covered by

4052.

The Commissioner did just that. When the IRS promulgated Temporary Treasury Regulation 145.4052-1, it was only complying with

the explicit requirements of 4052. As with 4221 and its implementing regulations, the IRS required with respect to 4052 that

manufacturer-sellers and dealer-purchasers be registered with the IRS

under 4222 and that the manufacturers obtain exemption certificates

containing statements from the dealer-purchasers that the trucks being

sold were for resale or long-term leasing. Even if 4052 had not

explicitly authorized such a regulatory scheme, however, Regulation

145.4052-1 would have been a reasonable promulgation designed to

verify that the excise tax had been paid by the dealer before exempt-

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

ing the manufacturer. It therefore would undoubtedly have been

within the IRSs authority.

As for Volvos argument that the regulation violated congressional

intent, there is little need to address this point further because, as

already noted, the IRS received explicit authority to promulgate the

regulation. Moreover, Congress intent to authorize such a regulation

is manifested by the fact that in later changing the language of 4052,

Congress, albeit a different Congress, recognized that it was adopting

a new requirement that called for less documentation than it had

required in the 1983 version of 4052. See 26 U.S.C. 4052(g)

(2003) (deleting the registration requirement and authorizing the

endorsement of a simple affidavit by the purchasing dealer on the

sales invoice that "such sale is for resale"). In recognizing that the

registration and certification requirements of the 1983 version of

4052 were too onerous, Congress also recognized that it would have

to rewrite the old version before the Commissioner could discard

those onerous requirements. Thus, Congress recognized that, at the

time the IRS promulgated Temporary Treasury Regulation

145.4052-1 (1988), it was the then-current Congress intent that the

IRS issue such a regulation.

Volvo also argues that the regulation was arbitrary and capricious

in that it created the possibility of double taxation. This argument,

however, is not based on the traditional understanding of double taxation referring to taxing a single transaction twice because, in the

circumstances before us, there are actually two transactions in play:

the sale by the manufacturer to the dealer and the sale by the dealer

to the user. Even if both transactions were taxed, the taxation would

not amount to double taxation in the traditional sense. Using "double

taxation" in a nontraditional sense, as Volvo would prefer for its argument i.e., to refer to any instance where a taxpayer pays a tax for

which it could have been exempt would render almost any documentation requirement violative of this "double taxation" prohibition.

Tax exemptions generally rely on taxpayers ability to prove their eligibility, and the IRSs actions in demanding such proof are not arbitrary and capricious merely because some taxpayers do not take

advantage of all exemptions. Volvo has no legal authority or plausible

legal theory to support its argument that the fact that its noncompli-

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

ance could result in taxation to both Volvo and its dealers renders the

IRSs regulation arbitrary or capricious.

Finally, Volvo makes the astonishing argument that in order to

avoid arbitrariness and capriciousness, "an administrative agency

must uniformly apply its regulations to all applicable situations."

Such a standard would be impossible for any agency to achieve. The

inherently discretionary nature of enforcement duties means that, in

the absence of an unconstitutional motive, the agency cannot be

required to apply each of its regulations mechanically to every situation that falls under them.

In sum, we find no merit in any of Volvos arguments that Temporary Treasury Regulation 145.4052-1 was invalid.

III

Volvo next contends that it "made a good faith effort to comply"

with Temporary Treasury Regulation 145.4052-1 and that, under

the doctrine of substantial compliance, it is entitled to a refund. Volvo

asserts that its substantial compliance with the regulation is a question

of fact that cannot be properly resolved by summary judgment and

that therefore we must remand this issue to the district court for trial.

Even as Volvo recognizes that it failed to obtain proper certifications

from three dealers Atlas, Alaska, and Alameda it proffers in

support of its substantial compliance claim evidence that suggests that

Alameda and Alaska were registered with the IRS and that they paid

some of the required excise taxes. Volvo also suggests that Alaskas

and Alamedas forms demonstrating payment of the excise tax have

been destroyed by the IRS. Finally, Volvo has presented evidence that

it made good-faith efforts to obtain certifications from its dealers but

that the dealers did not provide them. At bottom, it maintains that the

establishment of these facts and more would justify a factfinders

determination that Volvo had substantially complied with Regulation

145.4052-1.

At the outset, it must be noted that in circumstances where the IRS

was able to determine from its own records that Volvos dealers paid

the excise tax, the IRS refunded taxes to Volvo. Indeed, in response

to such an investigation, the IRS reduced its initial assessment of $2.1

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

million to $856,226. The IRS presses its claim for excise taxes from

Volvo in the circumstances where it has no record that the excise

taxes were paid.

Substantial compliance, as applied to tax regulation requirements,

must be seen as a limited exception to the general rule that "equitable

considerations are of limited consequence" in interpreting tax law

because "tax laws are technical and, for the most part, are to be

accordingly interpreted." Hull v. United States, 146 F.3d 235, 238

(4th Cir. 1998) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted). Even

so, the Tax Court has accepted substantial compliance with regulatory

requirements when the requirements "are procedural and when the

essential statutory purposes have been fulfilled." American Air Filter

Co. v. Commissioner, 81 T.C. 709 (1983). We have recognized a similar formulation, inquiring whether the failure to comply with a regulatory requirement "goes to the essence of the provision, or whether

it is merely a relatively ancillary, minor procedural infirmity." Atlantic Veneer Corp. v. Commissioner, 812 F.2d 158, 161 (4th Cir. 1987).

Believing that the dichotomy between "essential" and "procedural"

for this purpose is not satisfactory, the Seventh Circuit has suggested

a formulation that "[t]he common law doctrine of substantial compliance should not be allowed to spread beyond cases in which the taxpayer had a good excuse (though not a legal justification) for failing

to comply with either an unimportant requirement or one unclearly or

confusingly stated in the regulations or the statute." Prussner v.

United States, 896 F.2d 218, 224 (7th Cir. 1990) (en banc) (emphasis

added). To that end, before the doctrine of substantial compliance

could apply, there would have to be "a showing that the [regulatory]

requirement is either unimportant or unclearly or confusingly stated."

Id. at 224-25. And drawing on Prussner, the Fifth Circuit has articulated a similar formulation, holding that "substantial compliance is

achieved where the regulatory requirement at issue is unclear and a

reasonable taxpayer acting in good faith and exercising due diligence

nevertheless fails to meet it." McAlpine v. Commissioner, 968 F.2d

459, 462 (5th Cir. 1992).

All of these formulations seek to preserve the need to comply

strictly with regulatory requirements that are important to the tax collection scheme and to forgive noncompliance for either unimportant

and tangential requirements or requirements that are so confusingly

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

written that a good faith effort at compliance should be accepted.

Stated otherwise, a taxpayer may be relieved of perfect compliance

with a regulatory requirement when the taxpayer has made a good

faith effort at compliance or has a "good excuse" for noncompliance,

and (1) the regulatory requirement is not essential to the tax collection

scheme but rather is an unimportant or "relatively ancillary requirement" or (2) the regulatory provision is so confusingly written that it

is reasonably subject to conflicting interpretations.

When we apply such a formulation to this case, we readily conclude that Volvo cannot have the benefit of substantial compliance in

the circumstances presented. Regulation 145.4052-1 was clear and

unambiguous in requiring that Volvo and its dealers register with the

IRS in accordance with 4222 and that Volvo produce exemption

certificates from its dealers with respect to trucks sold to the dealer

for resale or for a long-term lease. Moreover, this provision was

essential to the IRSs tax collection effort in that it demonstrated

which party was responsible for the excise tax imposed by 4051.

The statute created a presumption that any sale, including the manufacturers sale to the dealer was, a "first retail sale," and therefore the

manufacturer owed the tax unless the dealer certified that it was purchasing the vehicle for resale. Thus, for example, if the dealer were

purchasing trucks for its own use or for a business of daily rentals,

the manufacturer would have to pay the excise tax itself. But if the

dealer were purchasing trucks for resale or long-term leasing and so

certified, the manufacturer would not have to pay the tax. Volvos

failure to provide the required demonstration that its dealers were purchasing trucks for resale thus left the tax regulation in its default

application, requiring Volvo to pay the excise tax.

The requirements of Regulation 145.4052-1 are not ancillary or

unimportant; they go to the essence of who owes the tax and how the

IRS can collect it. And the regulation itself established the importance

of the documentation by requiring it as a condition precedent to the

manufacturers exemption, providing that "[t]he sale of an article is

a taxable sale unless" the registration and certification requirements

are met. Temp. Treas. Reg. 145.4052-1(a)(2) (1988). In treating fulfillment of these requirements as a condition precedent to eligibility,

the IRS had support in its authorizing statute. Section 4222, on which

Congress directed the IRS to model its 4052 regulations, treats reg-

10

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

istration as a condition precedent for a manufacturer taxpayer to avail

itself of 4221s exemption. See 26 U.S.C. 4222(a) (providing that

the exemption "shall not apply . . . unless the [parties] are all registered under this section"). Thus, by referring to 4222, 4052

directed the IRS to treat registration as a condition precedent for eligibility for the tax exemption in 4051. The IRS was therefore within

its authority to require registration as a condition precedent to eligibility for the manufacturers exemption, rather than to treat it as an

unimportant procedural matter. Accordingly, the doctrine of substantial compliance cannot be applied in this case because it would excuse

noncompliance with essential regulatory requirements.

We should note that were we required to reach other aspects of the

substantial compliance formulation, we would have to question

whether Volvos efforts to comply with Regulation 145.4052-1

were in fact made in good faith. In its complaint and its brief on

appeal, Volvo has claimed that it relied on IRS agents misrepresentations regarding the requirements in Regulation 145.4052-1 even

though the regulation was clear and it understood its requirements.

Thus, Volvo alleged in its complaint that it did not take "steps to

obtain exemption certificates from its noncompliant dealers." Similarly in its brief on appeal, it stated, "Absent the IRS agents retreating

from their statements, Volvo would have followed the registration

requirements and obtained exemption certificates." In other words,

Volvo has actually acknowledged that it could have complied with

Regulation 145.4052-1 but chose not to. Instead, it relied on individual IRS agents assurances that it did not have to comply with the

regulation. No formulation of the substantial compliance doctrine

would award a tax refund to a taxpayer in these circumstances.

IV

Finally, Volvo contends that the district court erred in dismissing

its claim for a refund based on its allegations that the IRS should be

equitably estopped from enforcing Temporary Treasury Regulation

145.4052-1 against Volvo because individual IRS agents told Volvo

it did not have to comply with the requirements of the regulation.

In its complaint, Volvo alleged three instances when IRS agents

misrepresented what was required to satisfy Regulation 145.4052-1.

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

11

First, it alleged that during the first audit cycle, begun in 1991, an IRS

agent told Volvo that it did not need exemption certificates, but that

the IRS later changed its position. By this time, Volvo claimed, it

could not have obtained the required documentation. Second, it

alleged that also during the first audit cycle, the IRSs manager told

Volvo that exemption certificates would apply retroactively to qualify

as tax-exempt prior transactions between Volvo and the dealers. During the second audit cycle, however, another agent denied retroactive

effect to the certificates. Third and finally, Volvo alleged that sometime after February 13, 1995, an appeals officer told Volvo that the

IRS would accept affidavits in lieu of the specified certifications, but

the IRS did not do so. Volvo claims that it suffered a detriment in

receiving this misinformation because it "expended substantial

resources in obtaining" affidavits.

Equitable estoppel against the government is strongly disfavored,

if not outright disallowed, because it allows parties to collect public

funds in a situation not expressly authorized by Congress. Courts

should not "order[ ] recovery contrary to the terms of the regulation,

for to do so would disregard the duty of all courts to observe the conditions defined by Congress for charging the public treasury." OPM

v. Richmond, 496 U.S. 414, 420 (1990) (quoting Federal Crop Ins.

Corp. v. Merrill, 332 U.S. 380, 385 (1947)); see also Miller v. United

States, 949 F.2d 708, 712 (4th Cir. 1991). If equitable estoppel ever

applies to prevent the government from enforcing its duly enacted

laws, it would only apply in extremely rare circumstances. In "leav[ing] for another day whether an estoppel claim could ever succeed

against the Government," the Supreme Court has ominously observed

that "we have reversed every finding of estoppel that we have

reviewed." Richmond, 496 U.S. at 422-23.

In this case, each of Volvos allegations relates to an IRS agents

misrepresentation of the requirements of law, and it is well settled that

reliance upon statements or actions contrary to law is not reasonable.

See Fredericks v. Commissioner, 126 F.3d 433, 443 (3d Cir. 1997)

("[A] private partys reliance on governmental actions or omissions

is not reasonable if such acts or omissions are contrary to the law");

see also Miller, 949 F.2d at 712; Goldberg v. Weinberger, 546 F.2d

477, 481 (2d Cir. 1976); Posey v. United States, 449 F.2d 228, 23334 (5th Cir. 1997). Equitable estoppel requires reasonable reliance,

12

VOLVO TRUCKS OF NORTH AMERICA v. UNITED STATES

and we conclude that Volvo could not reasonably have relied upon

individual IRS agents representations that the unambiguous provisions of the law need not have been obeyed. Accordingly, we affirm

the district courts dismissal of Volvos claim based on equitable

estoppel.

V

For the reasons given, we affirm the district courts summary judgment entered on Volvos claims that Temporary Treasury Regulation

145.4052-1 was arbitrary and capricious and that Volvo substantially complied with the regulations requirements. We also affirm the

district courts order dismissing Volvos claim for equitable estoppel

under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) for failure to state a

claim upon which relief could be granted.

AFFIRMED

You might also like

- Moorish Science Handbook......... Goes With Circle 7.................................... Csharia LawDocument318 pagesMoorish Science Handbook......... Goes With Circle 7.................................... Csharia Lawamenelbey98% (52)

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Injustice and Bias in Canadian Family CourtroomsDocument50 pagesInjustice and Bias in Canadian Family CourtroomsMohamed Fidjel100% (1)

- Dutch Coffee Shops Symbolize Differences in Drug PoliciesDocument9 pagesDutch Coffee Shops Symbolize Differences in Drug PoliciesLilian LiliNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 2022 San Beda Red Book Labor Law and Social LegislationDocument196 pages2022 San Beda Red Book Labor Law and Social LegislationJohn Carlo Barangas100% (2)

- Davao Gulf Lumber v. CIR - Tax Exemption Strictly ConstruedDocument13 pagesDavao Gulf Lumber v. CIR - Tax Exemption Strictly ConstruedgsNo ratings yet

- Case Digest TaxationDocument20 pagesCase Digest TaxationGenevive GabionNo ratings yet

- GULF AIR vs. CIRDocument3 pagesGULF AIR vs. CIRAlyssa Clarizze MalaluanNo ratings yet

- TaxRev - CIR v. Liquigaz Philippines (A VOID FDDA Does NOT Render The Assessment Void)Document42 pagesTaxRev - CIR v. Liquigaz Philippines (A VOID FDDA Does NOT Render The Assessment Void)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Objectives and Risks for Payroll ManagementDocument2 pagesObjectives and Risks for Payroll ManagementEric Ashalley Tetteh100% (3)

- Summary of Significant SC Decisions (September-December 2013)Document3 pagesSummary of Significant SC Decisions (September-December 2013)anorith88No ratings yet

- CIR vs. Standard Chartered Bank Prescription RulingDocument2 pagesCIR vs. Standard Chartered Bank Prescription RulingGladys Bustria Orlino0% (1)

- Motion To Revive-FBRDocument3 pagesMotion To Revive-FBRreyvichel100% (2)

- CIR Vs La FlorDocument8 pagesCIR Vs La FlorJoshua Erik MadriaNo ratings yet

- Flowchart Institution of Proceedings For The Discipline of Judges and JusticesDocument1 pageFlowchart Institution of Proceedings For The Discipline of Judges and JusticesKristine Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Ordinance Electronic LibarayDocument4 pagesOrdinance Electronic LibarayRaffy Roncales2100% (1)

- Barredo vs. Hon. Vinarao, Director, Bureau of Corrections (Spec Pro)Document1 pageBarredo vs. Hon. Vinarao, Director, Bureau of Corrections (Spec Pro)Judy Miraflores DumdumaNo ratings yet

- Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Inc., and The Manufacturers Light and Heat Company v. United States, 446 F.2d 320, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document7 pagesColumbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Inc., and The Manufacturers Light and Heat Company v. United States, 446 F.2d 320, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument47 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CIR v. San Miguel Corporation G.R. No. 180740/G.R. No. 180910, November 11, 2019Document3 pagesCIR v. San Miguel Corporation G.R. No. 180740/G.R. No. 180910, November 11, 2019Ezi AngelesNo ratings yet

- Chevron Phils. vs. BCDADocument5 pagesChevron Phils. vs. BCDACharry DeocampoNo ratings yet

- Lee Polk v. Crown Auto, Incorporated, 228 F.3d 541, 4th Cir. (2000)Document4 pagesLee Polk v. Crown Auto, Incorporated, 228 F.3d 541, 4th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Lead Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 336 F.2d 134, 2d Cir. (1964)Document11 pagesNational Lead Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 336 F.2d 134, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Finals Case Digest 3 (1) Crim LawDocument78 pagesFinals Case Digest 3 (1) Crim Lawjulie anne serraNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue and Commissioner of Customs v. Philippines Airlines, Inc., G.R. Nos. 212536-37, August 27, 2014Document7 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue and Commissioner of Customs v. Philippines Airlines, Inc., G.R. Nos. 212536-37, August 27, 2014Christopher ArellanoNo ratings yet

- 153.CIR Vs La FlorDocument9 pages153.CIR Vs La FlorClyde KitongNo ratings yet

- CTA Rules on Prescription of Tax Refund ClaimDocument3 pagesCTA Rules on Prescription of Tax Refund ClaimHanilavMoraNo ratings yet

- CTA upholds BIR assessment of expanded withholding tax for 1998Document16 pagesCTA upholds BIR assessment of expanded withholding tax for 1998henzencameroNo ratings yet

- SC upholds CDC authority to impose fuel delivery fees in CSEZDocument150 pagesSC upholds CDC authority to impose fuel delivery fees in CSEZArianne CerezoNo ratings yet

- Dale Distributing Company, Inc. (Formerly Dale Radio Co., Inc.) v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 269 F.2d 444, 2d Cir. (1959)Document5 pagesDale Distributing Company, Inc. (Formerly Dale Radio Co., Inc.) v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 269 F.2d 444, 2d Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Petitioner, V. La Flor Dela Isabela, Inc., Respondent. DecisionDocument7 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue, Petitioner, V. La Flor Dela Isabela, Inc., Respondent. DecisionFrancis Coronel Jr.No ratings yet

- Tax Set 2Document30 pagesTax Set 2Nadine BediaNo ratings yet

- CIR V Next MobileDocument5 pagesCIR V Next MobilecarolNo ratings yet

- 3 - PHILEX v. CIR (G.R. No. 120324, April 21, 1999)Document6 pages3 - PHILEX v. CIR (G.R. No. 120324, April 21, 1999)Jaquelyn VidalNo ratings yet

- Philacor Credit Corporation V. Commissioner of Internal RevenueDocument10 pagesPhilacor Credit Corporation V. Commissioner of Internal RevenueCharity Gene AbuganNo ratings yet

- 47 Victoria Milling Co., Inc. v. Municipality of VictoriaDocument7 pages47 Victoria Milling Co., Inc. v. Municipality of VictoriaLean Gela MirandaNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs ShellDocument2 pagesCIR Vs ShellSherry Mae Malabago100% (1)

- Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Daughton, 262 U.S. 413 (1923)Document10 pagesAtlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Daughton, 262 U.S. 413 (1923)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- AVX LawsuitDocument15 pagesAVX LawsuitGabe CavallaroNo ratings yet

- CIR v. Aichi ForgingDocument5 pagesCIR v. Aichi Forgingamareia yapNo ratings yet

- Chevron Phils., Inc. vs. Bases Conversion Dev't AuthorityDocument6 pagesChevron Phils., Inc. vs. Bases Conversion Dev't AuthorityKevin LawNo ratings yet

- Presumption of regularity does not apply to tax delinquency salesDocument10 pagesPresumption of regularity does not apply to tax delinquency salesMelody Lim DayagNo ratings yet

- Travel Industries of Kansas, Inc. v. United States, 425 F.2d 1297, 10th Cir. (1970)Document4 pagesTravel Industries of Kansas, Inc. v. United States, 425 F.2d 1297, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LFLH) - . - .: Attacbed As "A"Document2 pagesLFLH) - . - .: Attacbed As "A"Chapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Petitioner, v. La Flor Dela Isabela, Inc., RespondentDocument9 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue, Petitioner, v. La Flor Dela Isabela, Inc., Respondentkristel jane caldozaNo ratings yet

- Polk v. Crown Auto Inc, 4th Cir. (2000)Document4 pagesPolk v. Crown Auto Inc, 4th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- General Electric Credit Corporation v. Strickle Properties, Ray Lyle and T.P. Strickland, 861 F.2d 1532, 11th Cir. (1988)Document8 pagesGeneral Electric Credit Corporation v. Strickle Properties, Ray Lyle and T.P. Strickland, 861 F.2d 1532, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument6 pagesCaseVanessa GaringoNo ratings yet

- CTA upholds tax assessmentsDocument11 pagesCTA upholds tax assessmentsClyde KitongNo ratings yet

- Paa Management, Ltd. v. United States, 962 F.2d 212, 2d Cir. (1992)Document11 pagesPaa Management, Ltd. v. United States, 962 F.2d 212, 2d Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SC upholds Victorias municipal ordinance taxing sugar mill despite exceeding regulatory costsDocument101 pagesSC upholds Victorias municipal ordinance taxing sugar mill despite exceeding regulatory costsRussel SirotNo ratings yet

- Dimitrios Avramidis v. Arco Petroleum Products Company, 798 F.2d 12, 1st Cir. (1986)Document9 pagesDimitrios Avramidis v. Arco Petroleum Products Company, 798 F.2d 12, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Significant SC (Tax) Decisions (September - December 2013)Document3 pagesSummary of Significant SC (Tax) Decisions (September - December 2013)Paterno S. Brotamonte Jr.No ratings yet

- Victorias Milling Co Inc Vs Municipality of VictoriasDocument8 pagesVictorias Milling Co Inc Vs Municipality of Victoriasandrea ibanezNo ratings yet

- SC upholds tax credit for senior citizen discountsDocument12 pagesSC upholds tax credit for senior citizen discountsDaizele Gayle GabrielNo ratings yet

- Standard Paving Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Standard Paving Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 190 F.2d 330, 10th Cir. (1951)Document5 pagesStandard Paving Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Standard Paving Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 190 F.2d 330, 10th Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs United Salvage Valid Assessment 1Document13 pagesCIR Vs United Salvage Valid Assessment 1Evan NervezaNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Philippine Airlines, Inc. G.R. Nos. 212536-37, August 27, 2014Document5 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue v. Philippine Airlines, Inc. G.R. Nos. 212536-37, August 27, 2014Jawa B LntngNo ratings yet

- AXDocument20 pagesAXDann MarrNo ratings yet

- Cir V United Salvage Full TextDocument13 pagesCir V United Salvage Full TextLeeJongSuk isLifeNo ratings yet

- CIR v. Pilipinas Shell 2012Document13 pagesCIR v. Pilipinas Shell 2012Elle BaylonNo ratings yet

- Central Cuba Sugar Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Central Cuba Sugar Co, 198 F.2d 214, 2d Cir. (1952)Document6 pagesCentral Cuba Sugar Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Central Cuba Sugar Co, 198 F.2d 214, 2d Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gulf Air Co-Phil Branch v. CIRDocument3 pagesGulf Air Co-Phil Branch v. CIRJustine GaverzaNo ratings yet

- BUREAU OF CUSTOMS V DevenashitDocument4 pagesBUREAU OF CUSTOMS V DevenashitJustine EspirituNo ratings yet

- Labor Cases Compilation For Page 17 - 18Document18 pagesLabor Cases Compilation For Page 17 - 18Jet VelazcoNo ratings yet

- Set 2 CasesDocument167 pagesSet 2 CasesElaine TalubanNo ratings yet

- Tax CasesDocument60 pagesTax CasesJapArcaNo ratings yet

- Davao Gulf LumberDocument13 pagesDavao Gulf LumberAnnamaAnnamaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 188497Document15 pagesG.R. No. 188497ericson dela cruzNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

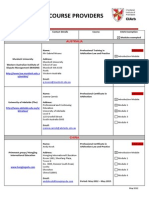

- Recognised Course Providers ListDocument13 pagesRecognised Course Providers ListSo LokNo ratings yet

- Should Business Lobbying Be Legalized in India - Implication On Business?Document6 pagesShould Business Lobbying Be Legalized in India - Implication On Business?Divyank JyotiNo ratings yet

- Employment Contract Know All Men by These Presents:: WHEREAS, The EMPLOYER Is Engage in The Business ofDocument3 pagesEmployment Contract Know All Men by These Presents:: WHEREAS, The EMPLOYER Is Engage in The Business ofHoney Lyn CoNo ratings yet

- Matibag Vs BenipayoDocument7 pagesMatibag Vs BenipayoMichael DonascoNo ratings yet

- LIABILITYDocument8 pagesLIABILITYkaviyapriyaNo ratings yet

- Bhutto & Zardari's Corruption Highlighted in Raymond Baker's Book On Dirty Money - Teeth MaestroDocument6 pagesBhutto & Zardari's Corruption Highlighted in Raymond Baker's Book On Dirty Money - Teeth Maestroسید ہارون حیدر گیلانیNo ratings yet

- 07 GR 211721Document11 pages07 GR 211721Ronnie Garcia Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Implementasi Rekrutmen CPNS Sebagai Wujud Reformasi Birokrasi Di Kabupaten BogorDocument14 pagesImplementasi Rekrutmen CPNS Sebagai Wujud Reformasi Birokrasi Di Kabupaten Bogoryohana biamnasiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Case DigestDocument7 pagesChapter 3 Case DigestAudreyNo ratings yet

- Solutions For Class 11political ScienceDocument5 pagesSolutions For Class 11political ScienceNityapriyaNo ratings yet

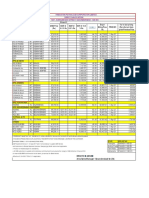

- HPCL PRICE LIST FOR VISAKH, MUMBAI, CHENNAI, VIJAYAWADA AND SECUNDERABAD DEPOTSDocument1 pageHPCL PRICE LIST FOR VISAKH, MUMBAI, CHENNAI, VIJAYAWADA AND SECUNDERABAD DEPOTSaee lweNo ratings yet

- United States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Vincent Gigante, Vittorio Amuso, Venero Mangano, Benedetto Aloi, Peter Gotti, Dominic Canterino, Peter Chiodo, Joseph Zito, Dennis Delucia, Caesar Gurino, Vincent Ricciardo, Joseph Marion, John Morrissey, Thomas McGowan Victor Sololewski, Anthony B. Laino, Gerald Costabile, Andre Campanella, Michael Realmuto, Richard Pagliarulo, Michael Desantis, Michael Spinelli, Thomas Carew, Corrado Marino, Anthony Casso, 187 F.3d 261, 2d Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Social Security CommissionDocument11 pagesGarcia vs. Social Security CommissionLyna Manlunas GayasNo ratings yet

- Annexure - E: Legal Security ReportDocument7 pagesAnnexure - E: Legal Security Reportadv Balasaheb vaidyaNo ratings yet

- Siemens Letter To PipistrelDocument2 pagesSiemens Letter To PipistrelRyan WagnerNo ratings yet

- 1-33504247894 G0057436708 PDFDocument3 pages1-33504247894 G0057436708 PDFAziz MalikNo ratings yet

- Handouts in Criminal Justice SystemDocument20 pagesHandouts in Criminal Justice SystemEarl Jann LaurencioNo ratings yet

- Form 842 PDFDocument34 pagesForm 842 PDFEhsan Ehsan100% (1)

- Rule 1 - Part of Rule 3 Full TextDocument67 pagesRule 1 - Part of Rule 3 Full TextJf ManejaNo ratings yet

- Police Officers For Good Government - 9723 - B - ExpendituresDocument1 pagePolice Officers For Good Government - 9723 - B - ExpendituresZach EdwardsNo ratings yet

- S.Govinda Menon v. Union of India AIR 1967 SC 1274 SummaryDocument2 pagesS.Govinda Menon v. Union of India AIR 1967 SC 1274 SummaryPrateek duhanNo ratings yet