Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States Court of Appeals: Published

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States Court of Appeals: Published

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

DEUNTE L. HUMPHRIES,

Defendant-Appellee.

No. 03-4567

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond.

Henry E. Hudson, District Judge.

(CR-03-100)

Argued: January 22, 2004

Decided: June 17, 2004

Before NIEMEYER, WILLIAMS, and GREGORY, Circuit Judges.

Reversed and remanded by published opinion. Judge Niemeyer wrote

the opinion, in which Judge Williams joined. Judge Gregory wrote an

opinion concurring in the judgment.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Richard Daniel Cooke, Special Assistant United States

Attorney, Alexandria, Virginia, for Appellant. Reuben Voll Greene,

JOHNSON & WALKER, P.C., Richmond, Virginia, for Appellee.

ON BRIEF: Paul J. McNulty, United States Attorney, Michael J. Elston, Assistant United States Attorney, Alexandria, Virginia, for

Appellant.

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

OPINION

NIEMEYER, Circuit Judge:

Deunte Humphries was arrested without a warrant in a high crime

area of Richmond, Virginia, after a Richmond police officer smelled

the odor of marijuana emanating from Humphries person and after

Humphries walked away from the officer, disobeying orders to stop

for questioning. At the time, the officer also had reason to suspect that

Humphries was carrying a concealed weapon.

Concluding that the officer did not have "probable cause to arrest"

Humphries, the district court suppressed the evidence seized as the

fruit of Humphries arrest.

Accepting the factual findings made by the district court, we conclude as a matter of law that the officer had probable cause to believe

that Humphries was committing a crime, justifying his arrest. Accordingly, we reverse the district courts suppression order and remand for

further proceedings.

I

On June 25, 2003, City of Richmond Police Officers Gary Venable

and A.D. Carr were patrolling an area of Richmond known for drug

trafficking. As the officers pulled their marked police car onto a block

with 5 to 15 persons "hanging outside" in the general area, Officer

Venable saw Deunte Humphries pat his waist area. Officer Venable,

a 16-year police veteran, interpreted the waist pat to be a "security

check"; he suspected that Humphries was instinctively confirming the

presence of his weapon by "checking to make sure it [was] there."

After they stopped their patrol car about 20 feet from Humphries

and exited the vehicle, the officers smelled a strong odor of marijuana. When Officer Venable began walking toward a man standing

near Humphries, he saw Humphries "out of the corner of [his] eye

quickly turn and quickly walk away." Officer Venable then followed

Humphries, saying to him, "I need to talk to you for a minute." Humphries did not answer and continued walking away at a quick pace.

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

As Officer Venable picked up his pace and got to within 5 to 10 feet

of Humphries, he smelled "the same strong odor of marijuana . . .

coming off of [Humphries] person" as that which he had smelled

upon exiting the patrol car. Officer Venable instructed Humphries to

stop, but Humphries continued walking away at the same quick pace.

As Humphries turned up a sidewalk to approach a house on the

3100 block of Fifth Avenue, Officer Venable again instructed Humphries to stop, but Humphries ignored the order and walked quickly

to the house and began knocking on the door. Officer Venable

stopped at the foot of the stairs to the house and noted that the smell

of marijuana remained strong and particularized to Humphries. After

Humphries knocked several times, a woman opened the door and

Humphries began to enter.

Officer Venable then said to Humphries, "Thats it. Stop. Dont go

in the house." Humphries ignored Officer Venables command and

walked into the house, glancing back at the officer. As Officer Venable stepped in the doorway and saw Humphries walk toward the

kitchen, Officer Venable told Humphries he was under arrest. Officer

Venable then went into the house and grabbed Humphries as he

started to round a corner and enter the kitchen.

As Officer Venable took Humphries outside of the house, he

smelled the odor of marijuana on Humphries breath. Officer Venable

patted Humphries down and recovered a 9mm semi-automatic handgun from the area where the officer had earlier seen Humphries pat

his waist. After recovering the weapon, Officer Venable conducted a

full search incident to arrest, finding 26 tablets of Percocet in Humphries jacket pocket and a small amount of crack cocaine in his pants

pocket.

Humphries was formally charged with possession of Percocet with

intent to distribute, simple possession of Percocet, possession of crack

cocaine, and possession of a firearm in furtherance of drug trafficking, in violation of 21 U.S.C. 841, 844 and 18 U.S.C. 924(c).

Before trial, he filed a motion to suppress the drug and handgun evidence seized incident to his arrest, contending that the evidence was

the fruit of an arrest that violated his Fourth Amendment rights. He

argued that Officer Venable did not have probable cause to arrest him,

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

nor did the officer have a "reasonable, articulable, particularized suspicion" of crime to stop him.

Following a hearing on Humphries motion, the district court

ordered the evidence suppressed. The court concluded that although

the information known to Officer Venable "was certainly enough to

give him the particularized suspicion necessary to stop the defendant

and to question him to allay his suspicion that the defendant may be

involved in the illegal possession or, perhaps more remotely, the distribution of marijuana," Officer Venable did not have probable cause

to arrest Humphries. The court apparently understood probable cause

to mean "more likely than not, [more than] 50/50."

The government filed this appeal, challenging the district courts

ruling suppressing the evidence seized incident to Humphries arrest.

II

The government does not challenge the district courts factual findings. Rather, it argues that based on the facts actually found by the

district court, Officer Venable had probable cause to arrest Humphries

and, incident to the arrest, to search him. Accordingly, the government asserts that the district court erred in suppressing the evidence

recovered from the search incident to the arrest. Humphries responds

simply by arguing that, as a matter of law, the evidence and inferences to be drawn therefrom were insufficient to establish probable

cause for his arrest.1

Our standard of review is familiar. While we review findings of

historical fact only for clear error, we review the determination of

probable cause de novo. Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690, 699

(1996). In our deference to fact-finding, we also give "due weight to

inferences drawn from those facts by resident judges and local law

enforcement officers." Id.

1

Humphries does not challenge Officer Venables warrantless entry

into the residence to make the arrest, presumably because Humphries

lacks standing, and therefore we treat his arrest as one made in a public

place.

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

The legal inquiry begins with the Fourth Amendment, which provides that the people are "to be secure in their persons . . . against

unreasonable searches and seizures . . . and no Warrants shall issue,

but upon probable cause." U.S. Const. amend. IV. This limitation is

made applicable to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment.

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25, 27-28 (1949). Under the Fourth

Amendment, if supported by probable cause, an officer may make a

warrantless arrest of an individual in a public place. Maryland v.

Pringle, 124 S. Ct. 795, 799 (2003); United States v. Watson, 423

U.S. 411, 424 (1976); Street v. Surdyka, 492 F.2d 368, 371-72 (4th

Cir. 1974) (holding that a warrantless arrest may be made in a public

place even if the crime for which the arrest was made was a misdemeanor committed outside an officers presence). "Probable cause"

sufficient to justify an arrest requires "facts and circumstances within

the officers knowledge that are sufficient to warrant a prudent person, or one of reasonable caution, in believing, in the circumstances

shown, that the suspect has committed, is committing, or is about to

commit an offense." Michigan v. DeFillippo, 443 U.S. 31, 37 (1979).

Determining whether the officer has probable cause involves an

inquiry into the totality of the circumstances. Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at

800. Moreover, the inquiry does not involve the application of a precise legal formula or test but the commonsense and streetwise assessment of the factual circumstances:

On many occasions, we have reiterated that the probablecause standard is a practical, nontechnical conception that

deals with the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal

technicians, act.

Id. at 799 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted). And as we

show deference to inferences that a resident judge draws from the factual circumstances, we show similar respect to the inferences drawn

by law enforcement officers on the scene. Id. at 799-800; Ornelas,

517 U.S. at 699.

In assessing the totality of the circumstances, it is appropriate to

consider specifically: an officers practical experience and the inferences the officer may draw from that experience, see Ornelas, 517

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

U.S. at 700; or the context of a high-crime area, see Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U.S. 119, 124 (2000); or an individuals presence in a highcrime area coupled with his "[h]eadlong flight" upon noticing police,

id.; or evasive conduct that falls short of headlong flight, United

States v. Lender, 985 F.2d 151, 154 (4th Cir. 1993); or even "seemingly innocent activity" when placed in the context of surrounding

circumstances, Porterfield v. Lott, 156 F.3d 563, 569 (4th Cir. 1998).

At bottom, however, the probable-cause standard is "incapable of precise definition or quantification into percentages because it deals with

probabilities and depends on the totality of the circumstances."

Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at 800. Stripped to its essence, the question to be

answered is whether an objectively reasonable police officer, placed

in the circumstances, had a "reasonable ground for belief of guilt" that

was "particularized with respect to the person to be searched or

seized." Id.

The facts found by the district court are undisputed. The court

found that as Officers Venable and Carr exited their vehicle in a highcrime area of Richmond, "they observed [Humphries] pat his waist

area." From 20 feet away, the officers detected the distinct odor of

marijuana, and they continued to smell the marijuana as they

approached Humphries and another man standing nearby. As the officers drew near, Humphries "turned and began to walk away," and

"Officer Venable told him to stop." Humphries did not stop but

walked away at "a quick pace." As Officer Venable followed "between 5 and 10 feet" behind Humphries, he continued to smell "the

distinct odor of marijuana." The district court found that Officer Venable directed Humphries to stop "on two occasions" but Humphries

ignored the orders. When Humphries approached a residence on the

3100 block of Fifth Avenue and knocked on the door, "Officer Venable stood at the foot of the stairs and still smelled . . . the odor of

marijuana around the defendant." After Humphries was admitted into

the premises by a woman, Officer Venable followed him and placed

him under arrest. The district court recognized that Officer Venable

was an experienced police officer and "what he had at that time in

front of him was the odor of marijuana emanating from the defendant

at the distance of between 5 and 10 feet."

With these undisputed facts, the legal question is now presented

whether Officer Venable had probable cause to believe that Humph-

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

ries "ha[d] committed, [was] committing, or [was] about to commit

an offense." DeFillippo, 443 U.S. at 37.

Under Virginia law, it is a crime to possess marijuana, Va. Code

Ann. 18.2-250.1, or to possess marijuana with the intent to distribute it, id. 18.2-248.1. It is also a crime to carry a concealed weapon

without a permit, id. 18.2-308, or to possess a firearm while possessing more than one pound of marijuana with the intent to distribute

it, id. 18.2-308.4.

We have repeatedly held that the odor of marijuana alone can provide probable cause to believe that marijuana is present in a particular

place. In United States v. Scheetz, 293 F.3d 175, 184 (4th Cir. 2002),

for example, we held that the smell of marijuana emanating from a

properly stopped automobile constituted probable cause to believe

that marijuana was in the vehicle, justifying its search. Similarly, in

United States v. Cephas, 254 F.3d 488, 495 (4th Cir. 2001), we recognized that the strong smell of marijuana emanating from an open

apartment door "almost certainly" provided the officer with probable

cause to believe that marijuana was present in the apartment. See also

United States v. Sifuentes, 504 F.2d 845, 848 (4th Cir. 1974) (holding

that officers sight of boxes inside a van coupled with the strong odor

of marijuana permitted seizure of the boxes because they were in

"plain view, that is, obvious to the senses"). While smelling marijuana

does not assure that marijuana is still present, the odor certainly provides probable cause to believe that it is. Thus, when marijuana is

believed to be present in an automobile based on the odor emanating

therefrom, we have found probable cause to search the automobile,

and when the odor of marijuana emanates from an apartment, we have

found that there is "almost certainly" probable cause to search the

apartment. A separate question, of course, remains in these circumstances whether an exception to the warrant requirement applies,

such as the automobile exception in Scheetz or the exigent circumstances in Cephas.

Humphries contends that these cases are inapposite because the

present case raises the issue of probable cause to arrest, not to search.

It is true that the inquiries about whether the facts justify a search are

different from whether they justify a seizure. In the search context,

the question is whether the totality of circumstances is sufficient to

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

warrant a reasonable person to believe that contraband or evidence of

a crime will be found in a particular place. Ornelas, 517 U.S. at 696;

Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 238 (1983). Whereas in the arrest context, the question is whether the totality of the circumstances indicate

to a reasonable person that a "suspect has committed, is committing,

or is about to commit" a crime. DeFillippo, 443 U.S. at 37. But in

both cases, the quantum of facts required for the officer to search or

to seize is "probable cause," and the quantum of evidence needed to

constitute probable cause for a search or a seizure is the same. 2

Wayne R. LaFave, Search & Seizure 3.1(b) (3d ed. 1996); compare

Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at 799-800 (arrest context), with Gates, 462 U.S.

at 230-32 (search context).

While the odor of marijuana provides probable cause to believe

that marijuana is present, the presence of marijuana does not of itself

authorize the police either to search any place or to arrest any person

in the vicinity. Additional factors must be present to localize the presence of marijuana such that its placement will justify either the search

or the arrest. In the case of a search, when the odor emanates from

a confined location such as an automobile or an apartment, we have

held that officers may draw the conclusion that marijuana is present

in the automobile or the apartment. See Scheetz, 293 F.3d at 184;

Cephas, 254 F.3d at 495. But probable cause to believe that marijuana

is located in an automobile or an apartment may not automatically

constitute probable cause to arrest all persons in the automobile or

apartment; some additional factors would generally have to be present, indicating to the officer that those persons possessed the contraband. See Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at 800-01 (holding that the presence of

cocaine and a roll of money in the passenger area of an automobile

gave officers probable cause to believe that the automobiles occupants jointly committed the crime of possession of cocaine). Thus, if

an officer smells the odor of marijuana in circumstances where the

officer can localize its source to a person, the officer has probable

cause to believe that the person has committed or is committing the

crime of possession of marijuana.

In this case, Officers Venable and Carr smelled a strong odor of

marijuana immediately upon exiting their patrol car about 20 feet

from Humphries. Humphries was not alone on the street, however, so

the odor could not initially be tied to Humphries alone. But when

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

Officer Venable followed Humphries as Humphries quickly walked

away, getting to within 5 to 10 feet of Humphries, he continued to

smell "the same strong odor of marijuana . . . coming off his person."

Officer Venable also smelled the odor of marijuana coming off Humphries as he knocked on the door of the residence that he entered to

evade the officer.

The district court credited Officer Venables testimony, and his testimony that the odor of marijuana followed Humphries down the

street was sufficient to particularize the source of the odor to Humphries person. Just as in Scheetz, 293 F.3d at 184, where the smell of

marijuana emanating from an automobile constituted probable cause

to believe marijuana was present in the vehicle, the odor of marijuana

emanating from Humphries was sufficient to provide Officer Venable

with probable cause to believe that marijuana was present on Humphries person. And because Officer Venable had probable cause to

believe Humphries was presently possessing marijuana, he had probable cause to arrest him for the crime of possession.

Other factors strengthen the conclusion that Officer Venable had

probable cause to arrest Humphries. Officer Venables probable-cause

calculation properly considered Humphries evasive conduct, even if

it fell short of "headlong flight." See Lender, 985 F.2d at 154. Humphries immediately walked away as the officers approached, and

although he did not run, he walked away at a quick pace, ignoring the

officers commands to stop. He also ignored the officers command

to stop before he entered a residence. Such evasive conduct would

suggest culpability to a reasonable officer.

In addition, as the police officers approached in their marked patrol

car, Humphries patted his waist, which Officer Venable interpreted as

a "security check," an instinctive check by Humphries to see that his

weapon was in place. Also, the entire encounter with Humphries took

place in an area known for drug trafficking. As an experienced police

officer, Officer Venable properly considered these circumstances in

his probable-cause calculation, because the increased possibility that

Humphries was carrying a weapon and was in an area known for drug

trafficking increased the possibility that Humphries was possessing

marijuana or other contraband. See Ornelas, 517 U.S. at 700 ("[A]

police officer may draw inferences based on his own experience in

10

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

deciding whether probable cause exists"); see also Porterfield v. Lott,

156 F.3d 563, 569 (4th Cir. 1998) ("[W]hen it is considered in the

light of all of the surrounding circumstances, even seemingly innocent activity may provide a basis for finding probable cause").

While the district court concluded that the circumstances that confronted Officer Venable provided the basis for a Terry stop, see Terry

v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968), the court rejected the claim that the circumstances provided probable cause because, as the court stated,

"probable cause means more likely than not, [more than] 50/50." If

the court rested its ultimate conclusion to suppress the evidence on

that understanding, it erred. The Supreme Court has repeatedly

admonished that the standard for probable cause is not "finely tuned"

or capable of "precise definition or quantification into percentages."

Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at 800. Indeed, the Court has explicitly admonished that the preponderance of the evidence standard, understood by

the district court in this case to apply, is inappropriate:

Finely tuned standards such as proof beyond a reasonable

doubt or by a preponderance of the evidence, useful in formal trials, have no place in the [probable-cause] decision.

Gates, 462 U.S. at 235, quoted in Pringle, 124 S. Ct. at 800. Similarly, we have stated that the probable-cause standard does not require

that the officers belief be more likely true than false. United States

v. Jones, 31 F.3d 1304, 1313 (4th Cir. 1994).

Because Officer Venable had probable cause to believe that Humphries was in possession of marijuana, he had authority to arrest him

without a warrant in a public place. See Watson, 423 U.S. at 424;

Street, 492 F.2d at 371-72. Accordingly, we reverse the district

courts order suppressing the evidence seized incident to Humphries

arrest and remand for further proceedings.

REVERSED AND REMANDED

GREGORY, Circuit Judge, concurring in the judgment:

I concur only in the judgment reached by the majority. Because the

district court correctly found that Officer Venable had reasonable sus-

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

11

picion to stop Humphries, detain him, and to even pat him down, the

arrest, whether valid or not, was harmless insofar as nothing additional was gained thereby. Accordingly, we need not reach the holding in the majoritys opinion.

I

Because the facts as stated in the majoritys opinion are sufficient,

I will move directly to the ultimate findings of fact made by the district court. After hearing the arguments of counsel and taking a short

recess, the district court made brief oral findings and ruled from the

bench. The court acknowledged that Officer Venable was "an experienced police officer who has testified many times in front of this

Court." J.A. at 95. The court also noted that Officer Venable smelled

marijuana "emanating from the defendant at the distance of between

5 and 10 feet." Id. Because the court was dissatisfied with the sole

"theory" offered during the suppression hearing by the Government

to support the arrest, id., Officer Humphries seemingly proceeded

directly to formal arrest, and because the Government was "steadfast

that there was probable cause to place the defendant under arrest," the

district court understandably granted the motion to suppress. J.A. at

96. In doing so, the court concluded that Officer Venable did not have

probable cause to arrest Humphries. To the contrary, however, the

Court found that "there was an abundance of information to allow

Officer Venable to conduct an investigative detention, to question this

defendant, and to perhaps pat him down for his safety." Id.

II

We review determinations of probable cause and reasonable suspicion de novo. United States v. Harris, 39 F.3d 1262, 1269 (4th Cir.

1994). A reviewing court, however, should take care to (1) review

findings of historical fact only for clear error, and (2) to give due

weight to inferences drawn from those facts by resident judges. Orleans v. United States, 517 U.S. 690, 699 (1996). This is true because

"a trial judge views the facts of a particular case in light of the distinctive features and events of the community. Such background facts

provide a context for the historical facts, and when seen together yield

inferences that deserve deference." Id.

12

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

The district court clearly found that Officer Venable had the requisite reasonable suspicion to stop and detain Humphries. In fact, the

district court found that "there was an abundance of information to

allow Officer Venable to conduct an investigative detention, to question this defendant, and to perhaps pat him down for his safety."1

Because the district court correctly found that Officer Venable was

justified in stoppingor attempting to stop, as it wereHumphries

and detaining him, and that he could have patted him down, United

States v. Hamlin, 319 F.3d 666, 671-72 (4th Cir. 2003), the fact that

Officer Venable "arrested" him first and then patted him down was,

at bottom, harmless. Even if the arrest were illegal, nothing was

gained from the arrest other than that which could have been properly

seized pursuant to the lawful pat-down and investigative detention.

Surely, evidence later seized, which could have been lawfully seized

earlier, is not fruit of a poisonous tree when the "tree" itselfthe stop

and pat-downwas never poisonous in the first instance.

When suppressing evidence as the fruit of an illegal arrest, the

guiding question is "whether, granting establishment of the primary

illegality, the evidence to which instant objection is made has been

come at by exploitation of that illegality or instead by means sufficiently distinguishable to be purged of the primary taint." Wong Sun

v. United States, 371 U.S. 471, 488 (1963) (citation omitted) (empha1

The district court disagreed with the Governments theory that Officer

Venable had probable cause to arrest Humphries for possession of marijuana. I note, however, that in the Governments brief it also argued in

opposition to the motion to suppress that the "arrest" of Humphries was

an "investigative detention." Indeed, the Governments brief before the

district court raised several theories to justify the arrest and pat-down,

including: probable cause that "criminal activity was afoot," J.A. at 23;

hot pursuit, id.; investigatory detention under Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1

(1968), id. at 24; and search incident to lawful arrest, id. at 25. Although

the Governments arguments certainly could have been more precise, the

district court was therefore not confined to one theory of arrest, i.e., for

a misdemeanor possession offense. Perhaps the district court may have

better understood the Governments arguments had the Government

argued specifically the theories asserted in their written briefs, instead of

devoting considerable oral argument to the holding of United States v.

Jones, 204 F.3d 541 (4th Cir. 2000), which is distinguishable from this

case.

UNITED STATES v. HUMPHRIES

13

sis added). In this case, there was no "primary illegality." And, it was

the pat-down that lead Officer Venable to the weapon and contraband;

there was no other intervening police action. Moreover, the purpose

of suppressing evidence is to prevent similar misconduct on the part

of the police in the future and to deny them any benefit from such

conduct. Although one might envision a differentperhaps even

bettercourse of action on the part of Officer Venable, it was hardly

misconduct. Officer Venable did not embark on a fishing expedition

merely hoping that "something might turn up." Brown v. Illinois, 422

U.S. 590, 605 (1975).2 Unlike the police misconduct in Brown, supra,

Humphries arrest was not effected for the purpose of obtaining evidence.

Accordingly, I would reverse the suppression order on the narrower

ground of harmless arrest.

2

In Brown, the Supreme Court reversed the Illinois Supreme Courts

per se rule that a confession that is otherwise improper under the Fifth

Amendment, may not be suppressed under the Fourth Amendment. 422

U.S. 590. The Court emphasized the prophylactic purposes of the Fourth

Amendment and held that a voluntary confession under the Fifth Amendment may be suppressed under the Fourth Amendment, as fruit of a poisonous tree, due to police misconduct, i.e., where "the detectives

embarked upon this expedition for evidence in the hope that something

might turn up [or where the manner an] arrest was affected gives the

appearance of having been calculated to cause surprise, fright, and confusion."

You might also like

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MB Spreads in USDocument14 pagesMB Spreads in USVienna1683No ratings yet

- A Brief History of SingaporeDocument16 pagesA Brief History of SingaporestuutterrsNo ratings yet

- Workings of Debt Recovery TribunalsDocument25 pagesWorkings of Debt Recovery TribunalsSujal ShahNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rogelio Reyes Rodriguez, A205 920 648 (BIA June 23, 2017)Document6 pagesRogelio Reyes Rodriguez, A205 920 648 (BIA June 23, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Leave Policy For BHEL: Page 1 of 4Document4 pagesLeave Policy For BHEL: Page 1 of 4Usama ZEshanNo ratings yet

- Rizona Ourt of PpealsDocument6 pagesRizona Ourt of PpealsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Russian Way of WarDocument98 pagesAnalyzing The Russian Way of WarMusculus Smederevo100% (1)

- Colinares vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesColinares vs. PeopleMichelle Montenegro - AraujoNo ratings yet

- RUBI v. Provincial BoardDocument3 pagesRUBI v. Provincial BoardMaila Fortich RosalNo ratings yet

- People V RamosDocument1 pagePeople V RamosMadelle PinedaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Deunte L. Humphries, 372 F.3d 653, 4th Cir. (2004)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Deunte L. Humphries, 372 F.3d 653, 4th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ronald Edward Havener, 77 F.3d 493, 10th Cir. (1996)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Ronald Edward Havener, 77 F.3d 493, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument12 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument13 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Daniel Raymond Frazier, 51 F.3d 287, 10th Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Daniel Raymond Frazier, 51 F.3d 287, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- U.S. Supreme CourtDocument11 pagesU.S. Supreme CourtprosfrvNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kenneth Newsome, 475 F.3d 1221, 11th Cir. (2007)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Kenneth Newsome, 475 F.3d 1221, 11th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gilmore, Irvin W. v. Zimmerman, Leroy, Attorney General For The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 793 F.2d 564, 3rd Cir. (1986)Document12 pagesGilmore, Irvin W. v. Zimmerman, Leroy, Attorney General For The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 793 F.2d 564, 3rd Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Donald Richard Munroe v. United States of America, Marian B. Munroe v. United States, 424 F.2d 243, 10th Cir. (1970)Document7 pagesDonald Richard Munroe v. United States of America, Marian B. Munroe v. United States, 424 F.2d 243, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Emma Rivera v. Paul Murphy, 979 F.2d 259, 1st Cir. (1992)Document8 pagesEmma Rivera v. Paul Murphy, 979 F.2d 259, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hernandez, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesUnited States v. Hernandez, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James Wren v. United States, 352 F.2d 617, 10th Cir. (1965)Document4 pagesJames Wren v. United States, 352 F.2d 617, 10th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America, Appellee-Cross-Appellant v. William Andrew Moore, James A. Carrington and Joseph Donahue, Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees, 968 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1992)Document15 pagesUnited States of America, Appellee-Cross-Appellant v. William Andrew Moore, James A. Carrington and Joseph Donahue, Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Appellees, 968 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Brito, 427 F.3d 53, 1st Cir. (2005)Document19 pagesUnited States v. Brito, 427 F.3d 53, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jesse Joe Alvarez, 116 F.3d 1489, 10th Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Jesse Joe Alvarez, 116 F.3d 1489, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Willie Brown and Anna Dunlap v. City of Belen, Sergeant Mike Chavez, City of Belen Police Officer, 141 F.3d 1184, 10th Cir. (1998)Document6 pagesWillie Brown and Anna Dunlap v. City of Belen, Sergeant Mike Chavez, City of Belen Police Officer, 141 F.3d 1184, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Iris Warner, 105 F.3d 650, 4th Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Iris Warner, 105 F.3d 650, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Sayles, 4th Cir. (1997)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Sayles, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument36 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Walter B. Lebowitz v. Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, 670 F.2d 974, 11th Cir. (1982)Document13 pagesWalter B. Lebowitz v. Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, 670 F.2d 974, 11th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Martin Jay Herman, 16 F.3d 418, 10th Cir. (1994)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Martin Jay Herman, 16 F.3d 418, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Sanchez, 519 F.3d 1208, 10th Cir. (2008)Document14 pagesUnited States v. Sanchez, 519 F.3d 1208, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument14 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Richard D. Fernandez, JR., United States of America v. Steven E. Granger, 58 F.3d 593, 11th Cir. (1995)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Richard D. Fernandez, JR., United States of America v. Steven E. Granger, 58 F.3d 593, 11th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Bobby R. Lindsey, 451 F.2d 701, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Bobby R. Lindsey, 451 F.2d 701, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Government of The Virgin Islands v. Felix Carrion Hernandez, 508 F.2d 712, 3rd Cir. (1975)Document10 pagesGovernment of The Virgin Islands v. Felix Carrion Hernandez, 508 F.2d 712, 3rd Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roland Augustus Hall v. United States, 418 F.2d 1230, 10th Cir. (1969)Document3 pagesRoland Augustus Hall v. United States, 418 F.2d 1230, 10th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. John Francis Butler v. James F. Maroney, Superintendent, State Correctional Institution, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 319 F.2d 622, 3rd Cir. (1963)Document13 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. John Francis Butler v. James F. Maroney, Superintendent, State Correctional Institution, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 319 F.2d 622, 3rd Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. David T. Felton, E-4270 v. Alfred T. Rundle, Superintendent, 410 F.2d 1300, 3rd Cir. (1969)Document13 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. David T. Felton, E-4270 v. Alfred T. Rundle, Superintendent, 410 F.2d 1300, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2014)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph Pellether, 469 F.3d 194, 1st Cir. (2006)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Pellether, 469 F.3d 194, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jamie Oporto, 74 F.3d 1250, 10th Cir. (1996)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Jamie Oporto, 74 F.3d 1250, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Romain, 393 F.3d 63, 1st Cir. (2004)Document16 pagesUnited States v. Romain, 393 F.3d 63, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William J. Stone v. Wayne K. Patterson, Warden, Colorado State Penitentiary, 468 F.2d 558, 10th Cir. (1972)Document3 pagesWilliam J. Stone v. Wayne K. Patterson, Warden, Colorado State Penitentiary, 468 F.2d 558, 10th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph Harley, 682 F.2d 398, 2d Cir. (1982)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Harley, 682 F.2d 398, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Brown, 4th Cir. (2010)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Brown, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument9 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Charles Palmer, 203 F.3d 55, 1st Cir. (2000)Document16 pagesUnited States v. Charles Palmer, 203 F.3d 55, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Donald Freeman Owens, 882 F.2d 1493, 10th Cir. (1989)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Donald Freeman Owens, 882 F.2d 1493, 10th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hawley, 10th Cir. (2016)Document16 pagesUnited States v. Hawley, 10th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Pulsifer, 10th Cir. (2014)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Pulsifer, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- TYRONE WERTS, Appellant v. Donald T. Vaughn The District Attorney of The County of Philadelphia The Attorney General of The State of PennsylvaniaDocument58 pagesTYRONE WERTS, Appellant v. Donald T. Vaughn The District Attorney of The County of Philadelphia The Attorney General of The State of PennsylvaniaScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Clyde Marvin Thompson, JR., 420 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1970)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Clyde Marvin Thompson, JR., 420 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wood v. County of Hancock, 354 F.3d 57, 1st Cir. (2003)Document17 pagesWood v. County of Hancock, 354 F.3d 57, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. MarineDocument10 pagesU.S. v. MarineScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Williams, 4th Cir. (1998)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Williams, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- State v. Zwicker, 2003-082 (N.H. Sup. CT., June 29, 2004)Document10 pagesState v. Zwicker, 2003-082 (N.H. Sup. CT., June 29, 2004)Chris BuckNo ratings yet

- United States v. Echevarria-Rios, 1st Cir. (2014)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Echevarria-Rios, 1st Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 42 U.S. Code 1983 - 2003 UpdatesDocument34 pages42 U.S. Code 1983 - 2003 UpdatesUmesh HeendeniyaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Allen Bamberger, 452 F.2d 696, 2d Cir. (1972)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Allen Bamberger, 452 F.2d 696, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Janet M. Hicks v. Richard D. Moore, 422 F.3d 1246, 11th Cir. (2005)Document10 pagesJanet M. Hicks v. Richard D. Moore, 422 F.3d 1246, 11th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roman Mordukhaev and Aaron Mordukhaev, 108 F.3d 330, 2d Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Roman Mordukhaev and Aaron Mordukhaev, 108 F.3d 330, 2d Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument43 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument15 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Holt v. U.S., 2002Document16 pagesHolt v. U.S., 2002R Todd HunterNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument27 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Story of Michael Brown: Behind the Fatal Shot Which Lit Up the Nationwide Riots & ProtestsFrom EverandThe Story of Michael Brown: Behind the Fatal Shot Which Lit Up the Nationwide Riots & ProtestsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- AutoText Technologies, Inc. v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Document2 pagesAutoText Technologies, Inc. v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- GR 158896 Siayngco Vs Siayngco PIDocument1 pageGR 158896 Siayngco Vs Siayngco PIMichael JonesNo ratings yet

- TortDocument11 pagesTortHarshVardhanNo ratings yet

- Ortega, Et Al. vs. CA, Et Al., 245 SCRA 529: VITUG, J.: G.R. No. 109248. July 3, 1995Document3 pagesOrtega, Et Al. vs. CA, Et Al., 245 SCRA 529: VITUG, J.: G.R. No. 109248. July 3, 1995Marites regaliaNo ratings yet

- Court rules on petition to dismiss criminal caseDocument1 pageCourt rules on petition to dismiss criminal caseBetson CajayonNo ratings yet

- Updated Bandolera Constitution Appendix A-General InfoDocument3 pagesUpdated Bandolera Constitution Appendix A-General Infoapi-327108361No ratings yet

- Alabang SupermarketDocument17 pagesAlabang SupermarketSammy AsanNo ratings yet

- Figueroa v. Commission On Audit20220701-11-1j2dg1zDocument33 pagesFigueroa v. Commission On Audit20220701-11-1j2dg1zTrea CheryNo ratings yet

- Vakalatnama Supreme CourtDocument2 pagesVakalatnama Supreme CourtSiddharth Chitturi80% (5)

- GR No. 189122: Leviste Vs CADocument11 pagesGR No. 189122: Leviste Vs CAteepeeNo ratings yet

- Taxation and Government Intervention On The BusinessDocument33 pagesTaxation and Government Intervention On The Businessjosh mukwendaNo ratings yet

- Order Against DLF LimitedDocument220 pagesOrder Against DLF LimitedShyam SunderNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Human Rights SystemDocument34 pagesThe Philippine Human Rights Systemfsed2011No ratings yet

- Identify Harassing Calls with Call TraceDocument3 pagesIdentify Harassing Calls with Call TracesayanNo ratings yet

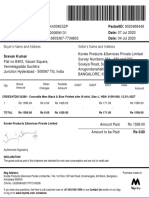

- Gstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Document1 pageGstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Sravan KumarNo ratings yet

- Crime and Punishment Around The World Volume 1 Africa and The Middle East PDFDocument468 pagesCrime and Punishment Around The World Volume 1 Africa and The Middle East PDFAnnethedinosaurNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Caroline Lang: Criminal Justice/Crime Scene Investigator StudentDocument9 pagesCaroline Lang: Criminal Justice/Crime Scene Investigator Studentapi-405159987No ratings yet

- Guarin v. Limpin A.C. No. 10576Document5 pagesGuarin v. Limpin A.C. No. 10576fg0% (1)

- Application FOR Customs Broker License Exam: U.S. Customs and Border ProtectionDocument1 pageApplication FOR Customs Broker License Exam: U.S. Customs and Border ProtectionIsha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 D Obligations With A Penal ClauseDocument3 pagesModule 5 D Obligations With A Penal Clauseairam cabadduNo ratings yet

- Checklist and Information Booklet For Surrender CertificateDocument3 pagesChecklist and Information Booklet For Surrender CertificateSasmita NayakNo ratings yet