Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Harry L. Core v. United States Postal Service, 730 F.2d 946, 4th Cir. (1984)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Harry L. Core v. United States Postal Service, 730 F.2d 946, 4th Cir. (1984)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

730 F.

2d 946

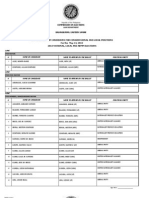

Harry L. CORE, Appellant,

v.

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE, Appellee.

No. 83-1153.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fourth Circuit.

Argued Aug. 29, 1983.

Decided Jan. 6, 1984.

Bernard J. DiMuro, Alexandria, Va. (Charles M. Rust-Tierney, Hirschkop

& Grad, P.C., Alexandria, Va., on brief), for appellant.

George E. Lawrence, Jr., Sp. Asst. U.S. Atty., Washington, D.C. (Elsie L.

Munsell, U.S. Atty., Alexandria, Va., Charles D. Hawley, Asst. Gen.

Counsel, Margaret O'Connell, General Administrative Law Div., U.S.

Postal Service, Washington, D.C., on brief), for appellee.

Before WINTER, Chief Judge, MURNAGHAN, Circuit Judge, and

BUTZNER, Senior Circuit Judge.

BUTZNER, Senior Circuit Judge:

Harry L. Core appeals from the district court's order denying his request under

the Freedom of Information Act for employment histories of applicants for

federal employment. We conclude that the Act requires release of the requested

information about the successful applicants, but 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552(b)(6)

(exemption 6) precludes disclosure of the other applications.

* In response to solicitations by the United States Postal Service, Core, a

Service employee, submitted an application for one of eight Systems Architect

positions. Upon inquiry about the status of his application, the Service notified

Core that five of the eight Systems Architect positions had been filled, that the

remaining three had been cancelled, and that he had not been among the final

candidates for any of the positions.

Core, believing that the Service had violated hiring regulations, initiated a

request for information about the education and automatic data processing

experience of the five persons selected as Systems Architects and of all other

applicants the Service deemed qualified for the position. The Service released

information on the educational qualifications of those applicants, but it denied

Core's request for information about experience gained through prior

employment. Relying on exemption 6, the Service concluded that disclosure of

this information would result in a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy

because it was inextricably interwoven with the textual summary of the

applications and was so detailed that individual applicants could be identified

even if their names were removed from the applications.

Core filed suit for disclosure. After hearing arguments on cross-motions for

summary judgment and examining the disputed documents in camera, the

district court concluded that release of the information would seriously invade

the privacy of the applicants because it would reveal that they were considering

leaving their present employment. According to the district court, disclosure

could lead to embarrassing speculation about the applicants' reason for leaving

their jobs and adversely affect their future employment or promotion.

Additionally, the district court concluded that the detailed narrative information

on the applicants' employment history, accomplishments, and self-evaluation is

ordinarily submitted with the expectation that it will remain private. Finding no

countervailing public interest in releasing the documents, the district court

denied Core's request.

II

5

The Freedom of Information Act establishes a general policy of full disclosure

unless the information requested is clearly exempted. Department of Air Force

v. Rose, 425 U.S. 352, 361, 96 S.Ct. 1592, 1599, 48 L.Ed.2d 11 (1976).

Exemption 6 excludes from the Act "personnel and medical files and similar

files the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of

personal privacy." The purpose of exemption 6 is to protect individuals from

the injury and embarrassment that can result from the unnecessary disclosure of

personal information. Department of State v. Washington Post Co., 456 U.S.

595, 599, 102 S.Ct. 1957, 1959, 72 L.Ed.2d 358 (1982).

In Washington Post, the Court held that the term, "similar files," includes all

files which contain information about a particular individual. 456 U.S. at 602,

102 S.Ct. at 1961. If the files fall within this definition, the remaining issue is

whether disclosure would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal

privacy. This determination requires "a balancing of interests between the

protection of an individual's private affairs from unnecessary public scrutiny,

and the preservation of the public's right to government information." S.Rep.

No. 813, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 9 (1965); see Rose, 425 U.S. at 370-82, 96 S.Ct.

at 1603-08.

III

7

Core requested information that is contained in the applications submitted for

the Systems Architect positions. These applications typically describe prior

Postal or business employment, special assignments or projects, membership in

any professional or civic organizations, awards and honors. If the applicant is

presently an employee of the Service, the application includes supervisors'

recommendations.* Because this information pertains to particular individuals,

it clearly falls within the "similar files" definition of Washington Post, 456 U.S.

at 602, 102 S.Ct. at 1961.

The next inquiry is whether the applicants' privacy interest outweighs the

public interest in disclosure. To balance these interests we have examined the

applications, and we agree with the district court that the information which

Core seeks about the applicants' experience in automatic data processing is

generally set forth in narrative summaries that disclose names of present and

former employers, awards, commendations, and membership in professional

organizations. We also agree that because the information Core seeks is not

reasonably segregable from the narratives, the Service is not obliged to extract

it. See 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552(b).

Unlike the district court, we conclude that the commingling of information that

characterizes the applications does not justify withholding information about

the five applicants who were selected for the positions. Their identity is known.

The disclosure that they wished to leave their former employment cannot

embarrass them, for this fact is now known to their former employers. The

information they furnished is not derogatory. It is simply the type of

information every applicant seeks to bring to the attention of a prospective

employer. In short, disclosure of information submitted by the five successful

applicants would cause but a slight infringement of their privacy. In contrast,

the public has an interest in the competence of people the Service employs and

in its adherence to regulations governing hiring. Disclosure will promote these

interests.

10

Having balanced the privacy interests of the five successful applicants against

the public's interest, we conclude that disclosure would not "constitute a clearly

unwarranted invasion of personal privacy." Exemption 6, therefore, does not bar

disclosure of the information Core seeks about the successful applicants.

11

Our conclusion is consistent with the policy of the Department of Justice which

discloses, in response to requests for information about its employees, prior

government employment, prior private employment related to current duties,

awards, honors, and membership in professional groups. The Department

recommended its policy to all agencies. See Office of Information and Privacy,

U.S. Dept. of Justice, FOIA Update 3 (Sept.1982). Although the Department's

interpretation of the statute is not binding on other agencies, Congress directed

the Department to report its efforts to encourage agencies to comply with the

Act. 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552(d). Consequently, the policies that the Department

recommends to other agencies merit careful consideration.

12

With respect to the unsuccessful applicants, the balance tips the other way.

Even if their names were deleted, the applications generally would provide

sufficient information for interested persons to identify them with little further

investigation. Though the unsuccessful applicants about whom Core requested

information were deemed qualified by the officials who reviewed the files,

ultimately they were rejected after interviews by the selecting official. In

contrast to the lack of harm from disclosure of the applications of persons who

are hired, disclosure may embarrass or harm applicants who failed to get a job.

Their present employers, co-workers, and prospective employers, should they

seek new work, may learn that other people were deemed better qualified for a

competitive appointment. It is no answer to say that only Core seeks

information about the unsuccessful applicants and that his purpose is benign. If

Core is entitled to information about unsuccessful applicants for a government

job, other members of the public, including employers and employment

agencies, would be entitled to the same information in this and other instances.

See Environmental Protection Agency v. Mink, 410 U.S. 73, 79, 93 S.Ct. 827,

832, 35 L.Ed.2d 119 (1973).

13

On the other side of the scale, the public interest in learning the qualifications

of people who were not selected to conduct the public's business is slight.

Disclosure of the qualifications of people who were not appointed is

unnecessary for the public to evaluate the competence of people who were

appointed. Indeed, comparison of all applications may be misleading, because

the appointments were made on the basis of both the applications and

interviews.

14

In Washington Post, the Court observed that in striking a balance between

privacy and disclosure, Congress intended to exclude from disclosure those

kinds of files which "might harm the individual." 456 U.S. at 599, 102 S.Ct. at

1959. Tested by this criterion, disclosure of information about unsuccessful

applicants for a Service job would be a clearly unwarranted invasion of their

personal privacy.

15

The judgment of the district court is affirmed in part and reversed in part, and

this case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Because Core has substantially prevailed, on remand the district court should

consider his request for a reasonable attorney's fee for services in the district

court and on appeal. 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552(a)(4)(E).

Core did not request supervisors' recommendations. These are set forth on a

separate page and easily can be withheld from disclosure. Core also requested

the Service to excise the names, addresses, and Social Security numbers of all

applicants. These, too, can be deleted readily. 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552(b)

You might also like

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Student Chapters-Eeri Authorization and RegulationsDocument2 pagesStudent Chapters-Eeri Authorization and RegulationsOana Alexandra IagărNo ratings yet

- UPSC AdvtDocument6 pagesUPSC AdvtgoldenyogNo ratings yet

- Halil İnalcık - A Case Study in Renaissance Diplomacy The Agreement Between Innocent VIII and Bayezid IIDocument15 pagesHalil İnalcık - A Case Study in Renaissance Diplomacy The Agreement Between Innocent VIII and Bayezid IIHristijan Cvetkovski100% (1)

- European History 1789-1870 ExamDocument4 pagesEuropean History 1789-1870 ExamAIM INSTITUTENo ratings yet

- Original MSGDocument40 pagesOriginal MSGgonzaloantoniochaconNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs September 2015Document470 pagesCurrent Affairs September 2015Anonymous 4qGUrAg7Dm100% (1)

- Background of Indian Foreign PolicyDocument23 pagesBackground of Indian Foreign PolicyAchanger AcherNo ratings yet

- Eng GTP2014 AR Full PDFDocument220 pagesEng GTP2014 AR Full PDFSanti SinnakaudanNo ratings yet

- RizalDocument44 pagesRizalAngelica SolomonNo ratings yet

- Executive Order 5 YEAR BDPDocument2 pagesExecutive Order 5 YEAR BDPrhenz villafuerteNo ratings yet

- Cement IndustryDocument3 pagesCement IndustryMadanKarkiNo ratings yet

- Whether Beaumont was a valid agent for customs protestDocument1 pageWhether Beaumont was a valid agent for customs protestAbegail GaledoNo ratings yet

- 27 Universal Robina Sugar Milling Corp. v. AciboDocument15 pages27 Universal Robina Sugar Milling Corp. v. AciboCristelle FenisNo ratings yet

- MLS ReviewDocument7 pagesMLS ReviewAzhari AhmadNo ratings yet

- Bautista vs. JuinioDocument1 pageBautista vs. JuinioOmen CaparidaNo ratings yet

- Robin V HardawayDocument22 pagesRobin V HardawayJohn Boy75% (4)

- National Institute For Smart GovernmentDocument5 pagesNational Institute For Smart GovernmentwkNo ratings yet

- Regulation: A PrimerDocument128 pagesRegulation: A PrimerMercatus Center at George Mason UniversityNo ratings yet

- COA decisions on water district purchasesDocument3 pagesCOA decisions on water district purchasesAnisah AzisNo ratings yet

- 19TH Century Philippines As Rizal's ContextDocument8 pages19TH Century Philippines As Rizal's Contextjaocent brixNo ratings yet

- Gen Ed Day 5Document9 pagesGen Ed Day 5luisgelacio19No ratings yet

- Two Bullets For PavelicDocument92 pagesTwo Bullets For PavelicKrešimir Matijević100% (1)

- Law Enforcement Against Use of Roadside by Street VendorsDocument13 pagesLaw Enforcement Against Use of Roadside by Street VendorsAxcellino FernandoNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Pakistani History (1947-Present) - WikipediaDocument32 pagesTimeline of Pakistani History (1947-Present) - WikipediaShehzad Ullah0% (1)

- Percy Bonilla v. Baker Concrete, 487 F.3d 1340, 11th Cir. (2007)Document9 pagesPercy Bonilla v. Baker Concrete, 487 F.3d 1340, 11th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 1 Revolution in 1896Document19 pages1 Revolution in 1896darren chenNo ratings yet

- (G.r. No. 252120) - in Re. The Petition For Writ of Amparo and Writ of Habeas Corpus in Favor of Alicia Jasper S. LucenaDocument6 pages(G.r. No. 252120) - in Re. The Petition For Writ of Amparo and Writ of Habeas Corpus in Favor of Alicia Jasper S. LucenaJane Marie DoromalNo ratings yet

- Notice: Application Accepted For Filing and Soliciting Comments, Motions To Intervene, and Protests: David Terry Hydro, LLCDocument2 pagesNotice: Application Accepted For Filing and Soliciting Comments, Motions To Intervene, and Protests: David Terry Hydro, LLCJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Balangkayan, Eastern SamarDocument2 pagesBalangkayan, Eastern SamarSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Christian EthicsDocument7 pagesChristian EthicsOlan Dave LachicaNo ratings yet