Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Viral Encephalitis

Uploaded by

DellCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Viral Encephalitis

Uploaded by

DellCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.

com

VIRAL ENCEPHALITIS: CAUSES,

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, AND

MANAGEMENT

i10

P G E Kennedy

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75(Suppl I):i10i15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034280

ncephalitis refers to an acute, usually diffuse, inflammatory process affecting the brain.

While meningitis is primarily an infection of the meninges, a combined meningoencephalitis

may also occur. An infection by a virus is the most common and important cause of

encephalitis, although other organisms may sometimes cause an encephalitis. An encephalitic

illness caused by alteration of normal immune function in the context of a previous viral infection

or following vaccination is also well recognised (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, ADEM).

An infectious encephalitis may also be difficult to distinguish from an encephalopathy that may

be associated with numerous metabolic causes. Among the factors which have helped to focus

attention on viral encephalitis over the last few years have been:

c the development of effective antiviral agents for this condition, most notably acyclovir for

herpes simplex virus encephalitis (HSE) which is caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 or

HSV-2

c the advent of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection of the central nervous system

(CNS) with its wide range of associated acute viral infections

c the recent recognition of emerging viral infections of the CNS such as West Nile encephalitis

and Nipah virus encephalitis.

This article will address three broad areas of viral encephalitisits causes, differential

diagnosis, and management. While the approach will be a general one, I shall focus particularly

on HSE which is the most frequent cause of sporadic fatal encephalitis in humans in the western

world.

_________________________

Correspondence to:

Professor P G E Kennedy,

Department of Neurology,

University of Glasgow, Institute

of Neurological Sciences,

Southern General Hospital,

Glasgow G51 4TF, UK;

p.g.kennedy@

clinmed.gla.ac.uk

_________________________

www.jnnp.com

CAUSES OF VIRAL ENCEPHALITIS

The various causes of acute infectious viral encephalitis are shown in table 1. While precise figures

for the incidence of encephalitis following these various viruses are not available, estimates have

been given for some of them. For example, it has been estimated that HSE, the most important

treatable viral encephalitis, has an incidence of about one case per million per year.1 About 2000

cases occur annually in the USA.2 About 90% of cases of cases of HSE are caused by HSV-1, with

10% due to HSV-2, the latter usually being the cause of HSE in immunocompromised individuals

and neonates in which it causes a disseminated infection. Molecular analyses of paired oral/labial

and brain sites have indicated that HSE can be the result of a primary infection, a reactivation of

latent HSV, or a re-infection by a second HSV.1 These estimates of HSE may well be

underestimates as judged by the experience of individual neurological centres and detailed

studies using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Thus, a small PCR based study suggested that

up to a fifth of patients with HSE may have mild or atypical disease caused by either HSV-1 or

HSV-2, occurring especially in immunocompromised individuals such as those with HIV

infection.3

A recent study in Finland also used PCR to detect various viruses in the CSF of over 3000

patients who had infections of the CNS including encephalitis, meningitis, and myelitis.4 It was

found that, rather surprisingly, varicella zoster virus (VZV), the cause of chickenpox and herpes

zoster, was the most frequently detected virus at 29%, with HSV and enteroviruses accounting for

11% of cases each, and influenza A virus found in 7% of cases. If one assumes a cause-and-effect

relation between the detected virus and the CNS condition in a significant proportion of these

cases, then it indicates that VZV has been generally underestimated, and HSV perhaps

overestimated in frequency. Nevertheless HSV detection in viral encephalitis is still critical

because there is effective treatment for it. Further prospective PCR based studies will be needed to

answer these questions.

While HIV has not been listed as it usually causes a type of subacute encephalitis, it is

important in so far as its associated immunosuppression predisposes the individual to viral

encephalitis caused by, for example, HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). The

frequency and distribution of these viruses clearly varies according to the geographical region,

with large differences seen between Europe, Asia, and the USA. Thus, St Louis virus encephalitis,

which is caused by a mosquito borne arbovirus, occurs in the midwestern and eastern states of the

NEUROLOGY IN PRACTICE

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

USA, and not in the UK, while Japanese encephalitis is a

major problem in Asia, and is the most important cause of

epidemic encephalitis worldwide, causing up to 15000 deaths

annually.5 Two emerging viral infections of the nervous

system which have received much attention recently are West

Nile virus encephalitis and Nipah virus encephalitis. The

former is caused by the transport of neurovirulent strains of

West Nile virus into the Western hemisphere, while the latter

has resulted from the penetration of a newly recognised

paramyxovirus across a species barrier from bat to pig,6 and

represents the first large scale epizoonotic encephalitis

involving direct animal to human transmission.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF VIRAL ENCEPHALITIS

The characteristic presentation of viral encephalitis usually

consists of fever, headache, and clouding of consciousness

together with seizures and focal neurology in some cases.

However, the distinction between an infective viral encephalitis and a metabolic encephalopathy or ADEM may not

always be straightforward. Once a diagnosis of infective viral

encephalitis has been established it is then necessary to have

a clear investigative plan to try to determine the likely cause.

These three issues will now be considered in turn.

How can a viral encephalitis be distinguished from a

non-infective encephalopathy?

There are numerous medical conditions which may produce

an encephalopathic illness which may mimic viral encephalitis, and some of the most important of these are listed in

table 2. Particularly prominent among these are systemic

infections which can look very much like an encephalitis on

presentation. In patients recently returning from abroad,

particular vigilance must be paid to the possibility of such

non-viral infections as cerebral malaria which may be rapidly

fatal if not treated early. A number of metabolic conditions

including liver and renal failure and diabetic complications

may also cause confusion. The possible role of alcohol and

drug ingestion must always be considered. Table 2 also

indicates the need to sometimes consider some of the rarer

causes of encephalopathy where appropriate pointers exist.

While the distinction may not always be straightforward,

there are a number of clues which may indicate that the

patient has an infective viral encephalitis rather than a nonviral encephalopathy. Table 3 summarises the most important of these and indicates the need for a careful examination

and usually cranial imaging to exclude a structural lesion

followed by CSF examination. These various clues should not

be taken in isolation but considered as a whole to guide the

Table 1 Causes of viral encephalitis

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1, HSV-2)

Other herpes viruses: varicella zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus

(CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 6 (HHV6)

Adenoviruses

Influenza A

Enteroviruses, poliovirus

Measles, mumps and rubella viruses

Rabies

Arbovirusesfor example, Japanese B encephalitis, St Louis

encephalitis virus, West Nile encephalitis virus, Eastern, Western, and

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, tick borne encephalitis viruses

Bunyavirusesfor example, La Crosse strain of California virus

Reovirusesfor example, Colorado tick fever virus

Arenavirusesfor example, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Modified from Chaudhuri and Kennedy,9 with permission.

clinician, as not all of them are likely to be present in the

same patient. Thus, the author has seen one patient with a

proven metabolic encephalopathy who had a fluctuating

mental status, but has found that the presence or absence of

focal signs and seizures, the presence or absence of

electroencephalographic (EEG) changes, normal or otherwise

cranial imaging, and CSF profile have been particularly

helpful in making the distinction between these two

conditions.

How can an infective viral encephalitis be

distinguished from ADEM?

ADEM, also known as postinfectious encephalomyelitis,

usually follows either a vaccination within the preceding

four weeks, or an infection which may be a childhood

exanthema such as measles, rubella or chickenpox, or else a

systemic infection characteristically affecting the respiratory

or gastrointestinal systems.7 There is very good evidence from

various sources to suggest an immune pathogenesis of this

disorder, with an abnormal immune reaction directed against

normal brain. Potential immune mechanisms include molecular mimicry between epitopes expressed by myelin antigens

and viral or other pathogens, immune dysregulation, superantigen induction, and a direct result of the infection.8 It is

important to distinguish ADEM from acute infectious

encephalitis, acute non-infectious encephalitis, and an acute

metabolic or toxic encephalopathy.8 While the diagnosis may

not always be immediately obvious, there are a number of

helpful clues in the history, examination, and investigative

profile that may greatly assist in the distinction between

ADEM and an infectious encephalitis. These differences have

been very clearly identified by Davis7 and are summarised in

table 4. The typical clinical picture is of a younger person with

a history of vaccination or infection presenting abruptly,

without fever at the onset of symptoms, and with multifocal

neurological signs affecting both the CNS and possibly the

peripheral nerve roots.9 It should also be appreciated that

ADEM can also present with a very restricted neurological

picture such as transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, and

cerebellar ataxia, and differentiation from acute multiple

sclerosis can sometimes be difficult. As is the case for table 3,

these various diagnostic pointers should be taken together

and not in isolation when trying to make the diagnosis of

ADEM.

How can the likely cause of an acute infective

encephalitis be determined?

The possible viral causes of acute infectious encephalitis have

already been listed in table 1. There are also numerous nonviral causes of infectious encephalitis comprising various

bacteria, rickettsia, fungi, and parasites; these are broadly,

but not exhaustively, summarised in table 5. The general

diagnostic approach to the differential diagnosis which I shall

outline here is straightforward, and consists of the history,

examination and then general and neurological investigations. However, it should be appreciated that in approximately half of cases the cause of viral encephalitis is not

found.

Historical clues

A carefully taken history, usually obtained from the comatose

patients relatives, is of crucial importance in determining the

likely cause of encephalitis. The presence of a prodromal

illness, or a recent vaccination, may indicate ADEM, as would

www.jnnp.com

i11

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

Examination clues

Table 2 Common causes of encephalopathy

c

c

c

c

c

i12

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

c

Anoxic/ischaemic

Metabolic

Nutritional deficiency

Toxic

Systemic infections

Critical illness

Malignant hypertension

Mitochondrial cytopathy (Reyes and MELAS syndromes)

Hashimotos encephalopathy

Paraneoplastic

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Traumatic brain injury

Epileptic (non-convulsive status)

Reproduced from Chaudhuri and Kennedy,9 with permission.

a clinical development over a few days. A biphasic onset with

a systemic illness followed by CNS disease is characteristic of

enterovirus encephalitis.9 HSE usually has an abrupt onset

with rapid progression over a few days, but there are no

clearly distinguishing features that can be used to differentiate HSE from the other causes of viral encephalitis.7 A

history of recent travel and the geographical context of the

illness may also be important. For example, both cerebral

malaria and human African trypanosomiasis should be considered in a patient who has recently travelled to Africa,

Japanese encephalitis in the case of travel to Asia, and Lyme

disease in the case of travel to high risk regions of Europe and

the USA. A history of recent animal bites should raise suspicion of tick borne encephalitis or even rabies, and recent

contact with infectious conditions such as a childhood exanthema or polio may also be relevant. The occupation of the

patient may also be relevantfor example, a forest worker

may be exposed to tick bites and medical personnel may have

had recent exposure to individuals with infectious diseases.

The season may also be relevantfor example, Japanese

encephalitis is more common during the rainy season and

arbovirus infections in the USA are more frequent during the

summer and autumn months. Any predisposing factors

should also be noted such as immunosuppression caused

by disease and/or drug treatment. Individuals with organ

transplants are particularly prone to opportunistic infections

such as listeria, aspergillosis and cryptococcus, and HIV

patients are also prone to a variety of CNS infections including HSV-2 encephalitis and CMV infection. A possible history

of drug ingestion and/or abuse may also be highly relevant.

Table 3

NEUROLOGY IN PRACTICE

A thorough general examination may reveal systemic

features indicating, for example, involvement of the respiratory or gastrointestinal systems. Skin rashes may indicate

VZV or other viral infection such as measles, as well as nonviral causes such as rickettsial infection. Evidence of bites

may point towards a possible diagnosis of Lyme disease or

rabies. The incidence of cold sores in patients with HSE has

not been shown to be different from that in the normal

population and so they are not diagnostic.

Neurological examination may reveal focal features such as

fronto-temporal signs, aphasia, personality change, and focal

seizures which are characteristic of HSE, but such focality

may be minimal during acute viral encephalitis and may not

be diagnostic of a particular viral cause. It has recently been

recognised that about 20% of HSE cases may be relatively

mild and atypical without the typical focal features.3 Raised

intracranial pressure may be evident but does not necessarily

occur, certainly at the early stages. If the peripheral nervous

system is involved then this raises the possibility of the

encephalitis being ADEM or an infection with CMV, VZV or

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which can all produce a combination of central and peripheral signs. The presence of myelitis

or poliomyelitis points away from HSE and towards the

possibility of polio, enterovirus, or arbovirus infection

(especially West Nile virus and Japanese encephalitis).

Investigations

These are both general and specifically neurological.

General investigations include a routine full haematological and biochemical blood screen. A leucocytosis is common

in ADEM and a relative lymphocytosis may occur in viral

encephalitis. A leucopenia may occur in rickettsial infections,

and a very raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) might

suggest tuberculosis or underlying malignancy. A thin and

thick peripheral blood smear may be required in cases of

suspected cerebral malaria. Biochemical screening is required

in cases of suspected metabolic encephalopathy. A drug

screen and urine analysis may also be relevant in some cases.

A chest x ray should always be performed and if abnormal

raises the possibilities of tuberculosis, mycoplasma, malignancy, and legionella. Serological investigations may be

diagnostically useful but usually take over a week to perform

which is of no utility in the acute situation. However, the

presence of cold agglutinins can be quickly determined and,

if positive, indicate a diagnosis of mycoplasma; an enzyme

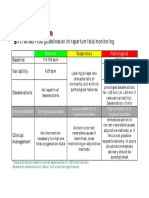

Frequent differences between encephalopathy and encephalitis

Clinical features

Fever

Headache

Depressed mental status

Focal neurologic signs

Types of seizures

Laboratory findings

Blood

CSF

EEG

MRI

Encephalopathy

Encephalitis

Uncommon

Uncommon

Steady deterioration

Uncommon

Generalised

Common

Common

May fluctuate

Common

Generalised or focal

Leucocytosis uncommon

Pleocytosis uncommon

Diffuse slowing

Often normal

Leucocytosis common

Pleocytosis common

Diffuse slowing and focal abnormalities

Focal abnormalities

Reproduced from Davis,7 with permission.

These features are only guidelines for the clinician to help in the distinction between the two conditions. An

individual patient is likely to show various combinations of these features.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EEG, electroencephalogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

www.jnnp.com

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NEUROLOGY IN PRACTICE

Table 4 Comparison of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and infectious encephalitis

Clinical features

Most common age

Recent vaccination

Prodromal illness

Fever

Visual loss (one or both eyes)

Spinal cord signs

Laboratory findings

Blood

MRI (T2 weighted)

CSF

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

Infectious encephalitis

Children

Common

Usually

May occur

May occur

May occur

Any age

Uncommon

Occasionally

Common

Uncommon

Rare

Leucocytosis occasionally occurs

Multiple focal areas of hypertensity that are the same

and may involve white matter of both hemispheres,

basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord

Lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, normal

glucose, and negative cultures. Red blood cells seen

in acute haemorrhagic leucoencephalitis.

Leucocytosis common

One or more diffuse areas of hypertensity involves the grey

matter of both cerebral cortices and its underlying white matter

and, to a lesser extent, basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum

Lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, normal glucose, and

negative cultures. Red blood cells may be seen in herpes simplex

encephalitis.

i13

Reproduced, in part, from Davis, with permission.

linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can detect IgM

antibodies to arboviruses as a rapid method of diagnosis.

Viral culture from different sites may assist in eventual

diagnosis, but in the authors opinion is seldom of use in the

acute situation.

Neurological investigation usually starts with cranial

imaging with a computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) scan, primarily to exclude quickly

an intracranial tumour or abscess, but also to yield specific

diagnostic information. MRI is the imaging of choice in

suspected cases of viral encephalitis, although CT scanning

may be used where MRI facilities are not available. CT may be

normal in HSE, especially early in the illness, but characteristically shows reduced attenuation in one or both temporal

lobes or areas of hyperintensity.7 MRI is sensitive in the early

stages of HSE although rarely it may be normal in this

Table 5 Non-viral causes of infectious encephalitis

Bacterial

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Listeria monocytogenes

Borrelia burgdorferi

Leptospirosis

Brucellosis

Leptospirosis

Legionella

Tropheryma whippeli (Whipples disease)

Nocardia actinomyces

Treponema pallidum

Salmonella typhi

All causes of pyogenic meningitis

Rickettsial

Rickettsia rickettsia (Rocky Mountain spotted fever)

Rickettsia typhi (endemic typhus)

Rickettsia prowazeki (epidemic typhus)

Coxiella burnetti (Q fever)

Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensishuman monocytic ehrlichiosis)

Fungal

Cryptococcus

Aspergillosis

Candidiasis

Coccidiomycosis

Histoplasmosis

North American blastomycosis

Parasitic

Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)

Cerebral malaria

Toxoplasma gondii

Echinococcus granulosus

Schistosomiasis

Modified from Chaudhuri and Kennedy,9 with permission.

condition. The typical MRI features in HSE are areas of focal

oedema in the temporal lobes and orbital surface of the

frontal lobes as well as the insular cortex and angular gyrus10

(fig 1); abnormal areas may show enhancement with

gadolinium. Midline shift may be present in cases with

significant cerebral oedema. Some other types of viral

encephalitis such as Japanese encephalitis and eastern

equine encephalitis are also associated with particular MRI

abnormalities. Where available, functional imaging such as

SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) may

yield additional useful information in cases of viral encephalitisfor example, temporal lobe hyperperfusion may be a

marker of HSE. An EEG should also be performed in all cases

of possible encephalitis, and is particularly useful in the

distinction between encephalitis and metabolic encephalopathy. The EEG is invariably abnormal in HSE showing either

early non-specific slowing or later PLEDS (periodic

lateralising epileptiform discharges), although these are not

themselves diagnostic of HSE.

Figure 1 HSE. T2 weighted MRI showing extensive area of increased

signal in right temporal lobe and lesser involvement of the left.

Reproduced from Baringer10, with permission.

www.jnnp.com

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NEUROLOGY IN PRACTICE

i14

Figure 2

Suggested flow chart for basic management of suspected herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE).

Provided cranial imaging has excluded any contraindications such as a space occupying lesion or severe cerebral

oedema and brain shift, a CSF analysis by lumbar puncture

should be carried out in cases of suspected encephalitis.

When significant cerebral oedema is present, I favour

treatment with steroids and/or mannitol to reduce the

intracranial pressure before lumbar puncture being reconsidered. Although about 5% of patients with HSE have a

normal CSF profile, the typical features of HSE are a

lymphocyte cell of 10200/mm3 and an increased protein of

0.66 g/l.11 A low CSF glucose is rare in viral encephalitis but

when it occurs it raises the possibility that the encephalitis is

actually caused by tuberculous meningoencephalitis. While

xanthochromia may be present in HSE it is of no specific

diagnostic value.10 The diagnosis of viral encephalitis has

been greatly facilitated by CSF PCR. In an experienced

diagnostic laboratory the CSF will should be positive for HSV

DNA in about 95% of cases during the first week of the

illness, with false negative results most likely occurring

within the first 2448 hours or after 1014 days of the illness.

The specificity of this test for HSE is over 95%. PCR can also

be used to help diagnose viral encephalitis from other causes

such as CMV, VZV, influenza, and enterovirus infection.

While serum and CSF are frequently taken for estimation of

viral antibody titres in the acute and convalescent phases,

these are of little value in the acute management of the

patient because of the delay in obtaining the results. Brain

biopsy is now seldom performed largely because of the

advent of acyclovir treatment (see below) and CSF PCR

www.jnnp.com

diagnosis, but still may have to be considered where there is

serious diagnostic doubt.

MANAGEMENT OF VIRAL ENCEPHALITIS

This can be considered from both the general and specific

aspects.

The general management is essentially supportive and in

severe cases is likely to be in a high dependency medical

environment. Focal and generalised seizures need to be

treated effectively with anticonvulsants, typically intravenous

fosphenytoin in the first instance. While a degree of raised

intracranial pressure, not requiring treatment, may well be

present in viral encephalitis, it may become severe as

evidenced by the development of papilloedema and rapid

clinical deterioration, and severe sulcal effacement and

midline shift on brain imaging. Such significantly raised

intracranial pressure should be treated with intravenous

mannitol and/or steroids. Despite the lack of an evidence

base, the author does not usually withhold steroids in this

situation, especially if the encephalitis is already being

treated with antiviral agents. In the case of rapidly increasing

intracranial pressure with clinical deterioration unresponsive

to medical treatment, very serious consideration should be

given to surgical decompression which can be lifesaving if

carried out in time. In addition, other complications such as

fluid and electrolyte imbalance, secondary bacterial infections, aspiration pneumonia, respiratory failure, and cardiac

abnormalities should be detected early and treated appropriately. In the case of ADEM, steroids are frequently given

NEUROLOGY IN PRACTICE

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

but in fact there have been no placebo controlled studies to

prove their efficacy or otherwise in this condition.

If antiviral therapy is not given to patients with HSE the

mortality is over 70%.12 Specific antiviral therapy for HSE is

intravenous acyclovir, a nucleoside analogue which acts

specifically against virus infected cells which explains its

remarkable safety and lack of toxicity. This drug has

revolutionised the treatment and prognosis of HSE, although

even with acyclovir therapy the morbidity and mortality is

unacceptably high at 28% at 18 months after treatment.12 If

HSE is a definite possibility then acyclovir, 10 mg/kg three

times daily, should be started as soon as possible. When the

diagnosis is confirmed by CSF PCR, and/or where there are

characteristic MRI changes, acyclovir should be continued for

14 days. During this period renal function should be closely

monitored because of the rare development of renal impairment. Acyclovir should only be stopped where there is a

definite alternative diagnosis made, otherwise a deterioration

after cessation of therapy may be very difficult to interpret

and manage.11 The situation of still suspected HSE in the

presence of a negative CSF PCR and MRI is less easy to

manage. My own preference is to give acyclovir for 10 days in

this scenario. This suggested scheme of management is

summarised in fig 2. The prognosis of HSE is better in

younger patients, and those having a disease duration of four

days or less and a Glasgow coma score of 6 or less at the time

of acyclovir initiation.12 In some centres the CSF PCR is

repeated at the end of acyclovir treatment and a further

course of acyclovir recommended if it is positive to prevent a

relapse.13 At present, the evidence base for this approach is

awaited and in the authors centre this is not routine practice.

However, the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group has just

initiated a study in which this issue will be clarified and also

the efficacy or otherwise of a 90 day course of oral

valacyclovir after 14 days of acyclovir treatment will be

determined. Thus this practice could become standard in the

future. For CMV encephalitis, particularly prominent in HIV

infection, combination therapy with intravenous gancyclovir

plus or minus foscarnet has been recommended,9 but there is

not the evidence base in this condition that exists in the case

of HSE therapy with acyclovir.

i15

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Professor Larry Davis for very helpful discussions and

his critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1 Whitley R, Laeman AD, Nahmias A, et al. DNA restriction enzyme analysis of

herpes simplex virus isolates obtained from patients with encephalitis.

N Engl J Med 1982;307:10602.

2 Johnston RT. Viral infections of the nervous system, 2nd ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

3 Fodor PA, Levin MJ, Weinberg A, et al. Atypical herpes simplex virus

encephalitis diagnosed by PCR amplification of viral DNA from CSF.

Neurology 1998;51:5549.

4 Koskiniemi M, Rantalaiho T, Piiparinen H, et al. Infections of the central

nervous system of suspected viral origin: a collaborative study from Finland.

J Neurovirol 2001;7:4008.

5 Solomon T. Recent advances in Japanese encephalitis. J Neurovirol

2003;9:27483.

6 Johnson RT. Emerging viral infections of the nervous system. J Neurovirol

2003;9:1407.

7 Davis LE. Diagnosis and treatment of acute encephalitis. The Neurologist

2000;6:14559.

8 Coyle PK. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis. In: Davis LE, Kennedy PGE, eds.

Infectious diseases of the nervous system, 1st ed. Butterworth-Heinemann,

2000:83108.

9 Chaudhuri A, Kennedy PGE. Diagnosis and treatment of viral encephalitis.

Postgrad Med J 2002;78:57583.

10 Baringer JR. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis. In: Davis LE, Kennedy PGE,

eds. Infectious diseases of the nervous system, 1st ed. Butterworth-Heinemann,

2002:13964.

11 Kennedy PGE, Chaudhuri A. Herpes simplex encephalitis. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:2378.

12 Whitley RJ, Gnann JW. Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging

pathogens. Lancet 2002;359:50714.

13 Cinque P, Cleator GM, Weber T, et al. The role of laboratory investigation in

the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected herpes simplex

encephalitis: a consensus report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiaryt

1996;61:33945.

www.jnnp.com

Downloaded from http://jnnp.bmj.com/ on April 28, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

VIRAL ENCEPHALITIS: CAUSES,

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, AND

MANAGEMENT

P G E Kennedy

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004 75: i10-i15

doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034280

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/75/suppl_1/i10

These include:

References

Email alerting

service

Topic

Collections

This article cites 9 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/75/suppl_1/i10#BIBL

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

box at the top right corner of the online article.

Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections

HIV/AIDS (104)

Immunology (including allergy) (1834)

Infection (neurology) (466)

Multiple sclerosis (882)

Spinal cord (515)

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- Disertasi Dr. TerawanDocument8 pagesDisertasi Dr. TerawanNurhaidah AchmadNo ratings yet

- B135 Work and EpilepsyDocument33 pagesB135 Work and EpilepsyDrSajid BuzdarNo ratings yet

- Labour and Delivery Care Module - 4 Using The Partograph - View As Single PageDocument21 pagesLabour and Delivery Care Module - 4 Using The Partograph - View As Single PageDellNo ratings yet

- Year 4 OSCEguideDocument159 pagesYear 4 OSCEguideDrSajid BuzdarNo ratings yet

- HTN Late PregnancyDocument2 pagesHTN Late PregnancyDellNo ratings yet

- KADDocument30 pagesKADDellNo ratings yet

- Module 14 Pediatric TB ENGLISHDocument85 pagesModule 14 Pediatric TB ENGLISHDellNo ratings yet

- Sliwa Et Al-2017-European Journal of Heart FailureDocument11 pagesSliwa Et Al-2017-European Journal of Heart FailureDellNo ratings yet

- KADDocument30 pagesKADDellNo ratings yet

- Nature CardiologyDocument7 pagesNature CardiologyDellNo ratings yet

- SalerioDocument28 pagesSalerioRizqaFebrilianyNo ratings yet

- GLM0021 Postpartum HaemorrhageDocument13 pagesGLM0021 Postpartum HaemorrhageDellNo ratings yet

- SPSS Crosstab PDFDocument3 pagesSPSS Crosstab PDFDellNo ratings yet

- Clinical Yeoh PDFDocument5 pagesClinical Yeoh PDFAzizan HannyNo ratings yet

- Year 4 OSCEguideDocument159 pagesYear 4 OSCEguideDrSajid BuzdarNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, Eighth Edition, 2 Volume SetDocument30 pagesFitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, Eighth Edition, 2 Volume SetDellNo ratings yet

- Clinical Diagnosis and Complications of Paratubal Cysts: Review of The Literature and Report of Uncommon PresentationsDocument10 pagesClinical Diagnosis and Complications of Paratubal Cysts: Review of The Literature and Report of Uncommon PresentationsDellNo ratings yet

- Sliwa Et Al-2017-European Journal of Heart FailureDocument11 pagesSliwa Et Al-2017-European Journal of Heart FailureDellNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0158499Document11 pagesJournal Pone 0158499DellNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Farmakologi Anti Konvulsi PDFDocument13 pagesJurnal Farmakologi Anti Konvulsi PDFtherempongss100% (1)

- NICEguidelineonAEDsAugust2014 0Document3 pagesNICEguidelineonAEDsAugust2014 0DellNo ratings yet

- Family Planning HandbookDocument387 pagesFamily Planning HandbookvthiseasNo ratings yet

- 5 Morisky Medication Adherence-Scale PDFDocument1 page5 Morisky Medication Adherence-Scale PDFDellNo ratings yet

- TB CutisDocument16 pagesTB CutisDellNo ratings yet

- CE-Hypertension The Silent KillerDocument8 pagesCE-Hypertension The Silent KillerD.E.P.HNo ratings yet

- A Practical Classification of Septonasal Deviation.42Document3 pagesA Practical Classification of Septonasal Deviation.42DellNo ratings yet

- CTG Classification PDFDocument1 pageCTG Classification PDFDellNo ratings yet

- 144TD (C) 25 (E3) - Issue No 3 - Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Infections Antibiotic Guidelines PDFDocument9 pages144TD (C) 25 (E3) - Issue No 3 - Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Infections Antibiotic Guidelines PDFDellNo ratings yet

- Jnma00266 0071Document4 pagesJnma00266 0071DellNo ratings yet

- Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery - American Family PhysicianDocument8 pagesFunctional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery - American Family PhysicianDellNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Postpartum Fever Presentation: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument14 pagesPostpartum Fever Presentation: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentRamandeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Document from அகத்தியன் அகாடமிDocument4 pagesDocument from அகத்தியன் அகாடமிarunkumarNo ratings yet

- ERYTHROLEUKOPLAKIADocument14 pagesERYTHROLEUKOPLAKIARajsandeep Singh100% (1)

- COVID-19's Impact on Student Lifestyles and Mental HealthDocument9 pagesCOVID-19's Impact on Student Lifestyles and Mental HealthAjay LakshmananNo ratings yet

- 248413-Article Text-594567-1-10-20230527Document8 pages248413-Article Text-594567-1-10-20230527Dewi RizkiNo ratings yet

- MCQ 2019 Part 1 UseDocument94 pagesMCQ 2019 Part 1 UseMimmey YeniwNo ratings yet

- Medical Certificate Form For Non Immigrant O A Long Stay OnlyDocument1 pageMedical Certificate Form For Non Immigrant O A Long Stay OnlyFiroz KhanNo ratings yet

- Presentation 5 The Infection Control Risk Assessment and PlanDocument24 pagesPresentation 5 The Infection Control Risk Assessment and PlanLany PasauNo ratings yet

- Supercare Medical Services, Inc. Health Declaration Form: Remarks of Examining PhysicianDocument1 pageSupercare Medical Services, Inc. Health Declaration Form: Remarks of Examining PhysicianJunexielJalop100% (1)

- Bleeding Disorders FinalDocument35 pagesBleeding Disorders FinalsanthiyasandyNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument28 pagesNephrotic Syndromerupali khillareNo ratings yet

- Diabetes MellitusDocument29 pagesDiabetes MellitusFourthMolar.com100% (1)

- Global Impact of The First Year of COVID-19 VaccinationDocument10 pagesGlobal Impact of The First Year of COVID-19 VaccinationRoel PlmrsNo ratings yet

- Necrotizing FasciitisDocument5 pagesNecrotizing Fasciitisnsl1225No ratings yet

- Exercise 4.1Document1 pageExercise 4.1Belle LatNo ratings yet

- 2014 Final Paediatric Exam (تم الحفظ تلقائيًا)Document258 pages2014 Final Paediatric Exam (تم الحفظ تلقائيًا)wea xcz100% (4)

- Morpheus8 Consent FormDocument3 pagesMorpheus8 Consent FormOnurNo ratings yet

- PCV Septia 2003Document16 pagesPCV Septia 2003WondaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Smear Positive PTBDocument40 pagesLecture 1 - Smear Positive PTBNasibah Tuan YaacobNo ratings yet

- Epstein-Barr Virus and MonoDocument2 pagesEpstein-Barr Virus and MonoMihai PetrescuNo ratings yet

- 紅白斑Document20 pages紅白斑b202104023 TMUNo ratings yet

- Dr. Dhani Redhono Hariosaputro, SP - PD-KPTI - Invasive Fungal Infection in SepsisDocument32 pagesDr. Dhani Redhono Hariosaputro, SP - PD-KPTI - Invasive Fungal Infection in SepsisOlivia DwimaswastiNo ratings yet

- Slow Contact Tracing' Blamed For Spread of New CoronavirusDocument6 pagesSlow Contact Tracing' Blamed For Spread of New CoronavirusProdigal RanNo ratings yet

- Community DentistryDocument5 pagesCommunity DentistryDenis BaftijariNo ratings yet

- Leg and Feet Swelling Natural RemediesDocument4 pagesLeg and Feet Swelling Natural Remediesghica05100% (1)

- Princess Arianne Macaranas Five Hello Rache PracticeDocument2 pagesPrincess Arianne Macaranas Five Hello Rache PracticeDianne MacaranasNo ratings yet

- RSV Bronchiolitis Discharge SummaryDocument2 pagesRSV Bronchiolitis Discharge SummaryIndranil SinhaNo ratings yet

- Toms River Regional School District Athletic Waiver and Release of Liability Form Related To COVID-19Document4 pagesToms River Regional School District Athletic Waiver and Release of Liability Form Related To COVID-19Asbury Park PressNo ratings yet

- Connect with a Vet for Canine Adenovirus 1 AdviceDocument3 pagesConnect with a Vet for Canine Adenovirus 1 Adviceaurrasinger9157No ratings yet

- Arora PLAB 2 60 Day Planner - Min2Document9 pagesArora PLAB 2 60 Day Planner - Min2malmegrimNo ratings yet