Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Holistic care model for hospitalized preschoolers

Uploaded by

Dani PhilipOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Holistic care model for hospitalized preschoolers

Uploaded by

Dani PhilipCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW

AN ADAPTATION OF THE NEUMAN

SYSTEMS MODEL TO THE CARE OF THE

HOSPITALIZED PRESCHOOL CHILD

J.P. Orr

INTRODUCTION

Abstract

A study was u n d e rta k en w herein a

nursing model was proposed to facilitate

the provision of holistic care for the

hospitalized preschool child. This was

done in an attempt to ensure that the

p h y s ic a l, e m o tio n a l, s o c ia l and

intellectual needs of the young child

could be all incorporated into his nursing

care.

This article describes an adaptation

o f the Neuman Systems Model to the

care o f the hospitalized preschool

child. This was done to unite the

physical care o f the hospitalized

preschool child with other aspects of

his development and to describe the

causes and prevention o f stresses o f

hospitalization for this child.

Kershaw and Salvage (1986: xii) state that

any model of nursing should be fluid and

dynamic so that it may be adapted or

modified to meet a specific need. The

Neuman Systems Model was selected as

a suitable framework within which to

o rg a n iz e th e n u rs in g c a re o f th e

h o sp ita liz ed p re sc h o o l child as its

emphasis on both system and stress

th e o ry a llo w e d fo r a m ea n in g fu l

in te r p re ta tio n o f th e p ro b lem s of

h o sp ita liz a tio n . In a d d itio n it had

potential for unifying the physical care of

the child with o th er aspects of his

development.

Opsomming

Hierdie ariikel beskryf n aunpassing

van die Neuman Systems Model vir

die sorg van die gehospitaliseerde

voorskoolse kind. Dit is ondemeem

o m die fis ie s e sorg van die

gehospitaliseerde kleuter met ander

aspekte van sy ontw ikkeling te

integreer, asook om die oorsake en

v o o rk o m in g van die stres van

hospitalisasie te beskryf.

DESCRIPTION OF THE NEUMAN

SYSTEMS MODEL

The Neuman Systems Model, as appears

in Neuman (1989: 26), subsequently was

a d a p te d in an a tte m p t to p rovide

multifaceted care for the hospitalized

preschool child. Castledine maintains"...

that to adapt ormodify something implies

some form o f change in quality, so it fits

more easily that which was intended"

(Castledine 1986: 64). In this respect the

Neuman Systems Model was suitable as

it facilitated an understanding of the

interrelationship of the various factors

w hich m ak e th e e x p e rie n c e of

hospitalization stressful for the young

child. By beginning with the child and his

fam ily a n d p r o g re s s in g to th e

environm ent surrounding them , the

in te rd e p e n d e n c e of all the factors

r e q u ir e d fo r th e r e s to r a tio n or

m a in te n a n c e o f h e a lth was m ade

apparent.

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

The Neuman Systems Model emphasises

"wholeness... thus avoiding the fragmented

and isolated nature o f past functioning in

nursing" (Neuman 1982: 1). The basic

tenets of this model view man as an open

system in in te r a c tio n w ith his

environment and incorporate a total

person approach with the view to assist a

person "... to attain a maximal level o f

health through the use o f purposeful

interventions aimed toward strengthening

adaptive mechanisms, decreasing stress

factors, or decreasing adverse conditions"

(Neuman 1982: 118). The health of an

individual is considered in this model to

be determined by his reaction to stress.

Stressors in the environment may be

in tr a p e r s o n a l, in te r p e r s o n a l or

extrapersonal. Nursing is considered to

be a cooperative activity during which the

nurse assists the chent to cope with stress

at either a primary, secondary or tertiary

level so that the client may return to a

state of optimum stability and health

(Hawkins 1983: 31).

Basic a ssu m p tio n s regarding the

Neuman Systems Model

The following basic assumptions are

considered to be inherent in this model

(Neuman 1982: 12-14; Thibodeau 1983:

117-118; Whall 1983: 203; Neuman 1989:

25; Cross 1990: 261-262):

The client may be an individual, a

g ro u p such as a fam ily , or a

community;

Each client is an open system that is

d y n a m ic ally a n d c o n tin u a lly

in te ra c tin g w ith and reactin g to

stressors in the environment;

The individual client in a state of

w ellness or illness is a dynam ic

composite of the interrelationship of

p h y s io lo g ic a l,

p s y c h o lo g ic a l,

sociocultural, developm ental and

spiritual variables which are always

present;

Although each client is unique, each

client system is a com bination of

known c h a ra c te ristic s contained

within a basic core structure with a

normal range of response;

Stressors in the environment, which

may be physiological, psychological or

sociocultural, have the potential to

disturb a chents health and stabiUty;

th e s e m ay b e in tr a p e r s o n a l,

interpersonal or extrapersonal in

origin;

The degree to which a client reacts to

a s tre s so r is d e te rm in e d by his

defences and his personal perception

of it;

Each client develops a normal range

of response to the environment which

r e p r e s e n ts a d y n a m ic s ta te of

37

adaptation. This range of response is

called the normal line of defence or

usual wellness/stabiUty state;

Each client has a flexible line of

defence that constantly changes as a

result of stressors; such flexibility

cushions the client from stressors.

The interrelationship of physiological,

p s y c h o lo g ic a l,

s o c io c u ltu r a l,

developmental and spiritual variables

determine the nature and degree of

reaction to a stressor;

I Each "client system" has a set of

internal resistan ce factors which

endeavour to stabilize the client and

retu rn him to his norm al line of

defence and which are known as lines

of resistance;

' R e c o n stitu tio n in resp o n se to a

stressor results in the client achieving

another (higher or lower) state of

wellness than existed prior to the

stress reaction;

Prim ary prevention relates to the

assessment and reduction of risk

factors associated with environmental

stressors;

S eco n d ary p re v e n tio n re fe rs to

in te rv en tio n a fte r a re a c tio n to

stressors has occurred, so that their

negative effects may be reduced;

Tertiary prevention refers to that

readjustm ent which is required to

maintain stability.

NURSING INTERVENTION

PRIMARY PREVENTION

Health maintenance

Health promotion

Alternatives

for hospitalization

Prehospital preparation

Suitable environment

Parental presence

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Therapeutic play

T he a s su m p tio n s on w hich th e

adaptation of the N eum an Systems

Model are based are deduced from those

which appear in the previous section.

The person receiving care

In this model the person receiving care is

the preschool child viewed within the

context of his family. The "preschool

child" refers to the child under the age of

seven years and the terms "infant" and

"toddler" are not specifically used for the

younger child. This age group was

selected as it is the period during which

the child is most likely to be anxious and

d is tre s s e d

by th e

u n fa m ilia r

environment, the threatening nature of

medical procedures, separation from his

parents and his inability to correctly

perceive the passage of time. The child is

the primary system of focus with other

subsystems or suprasystems occurring in

relation to him. Although the function of

the nurse is to provide direct care to the

child, she will, in addition, have to focus

on all family members to assess the effect

of the childs illness on them. According

to Azarnoff & Hardgrove (1981: 18) the

treatment of sick children"... should take

into account their physical and emotional

environment ... [which includes their] ...

relationships with their families".

STRESSORS (More than one

can occur simultaneously)

th e

p h y s io lo g ic a l

v a r ia b le

incorporates the childs physical and

biological structure and functioning;

the psychological variable refers to

those processes related to emotional

BASIC STRUCTURE

Composite of variables

NORMAL UNE OF DEFENSE

//

Physiological

Psychological

Sociocultural

FLEXIBLE UNES OF RESISTANCE

Perception of illness and

the hospital

Personality

Past life experience

INTERPRESONAL

Separation anxiety

Parental anxiety

Unfamiliar personnel

Staffing ratios

Work allocation

TERTIARY PREVENTION

The individual child is considered to be

an interrelationship of physiological,

psychological, sociocultural, cognitive

and spiritual variables which comprise

subsystems within him. This deviates

slightly from the Neuman Systems Model

in that Neuman (1989) does not include

a cognitive variable but incorporates it

into the psychological variable. In this

model adaptation, the developmental

variable has been excluded as it appears

to be inherent in the other variables. The

variables are thus described as follows:

INTRAPERSONAL

Pain

Bodily intrution

Fear of mutilation

Letters, tapes

and telephone calls

Free visiting

Child life programmes

Play leader

Consistant caregiver

Each child, as well as the members of his

family, are considered to be in a state of

dynamic interaction with, and reaction

to, the stressors in the environment. The

child is seen as an open system protected

by c e r ta in d e fe n c e m e c h a n ism s

represented by a series of concentric

rings; these protect him from stressors in

the environment. Because of the age of

the preschool child, his parents Eire seen

to be one of the buffers or boundaries

which protect him from environmental

stressors and which serve to control the

dynamic exchange between him and the

environment. In addition to acting as a

boundary, the parents and sibUngs can

also be v iew ed as a s u p ra s y s te m

surrounding the child.

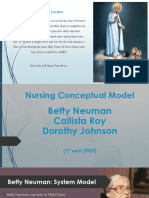

BASIC ELEMENTS IN THE

ADAPTATION OF THE NEUMAN

SYSTEMS MODEL FOR THE

PROVISION OF TOTAL CARE FOR

THE HOSPITALIZED PRESCHOOL

CHILD

Cognitive

LINES OF RESISTANCE

DMOtO

STRUCTURE

OF CHILD

Age

Sex

Prehospital preparation

Previous hospitalization

Sociocultural factors

LINES OF DEFENSE

EXTRAPERSONAL

Age

Developmental level

Parental presence

Unfamiliar environment

Change of routine

RECONSTITUTION

Peer and sibling visiting

Regression___________

Can begin at any

of the three levels

Figure 1

An adaptation of the Neuman Systems lUlodel

to the hospitalized preschool child

(adapted from : Neuman, B. 1989. The Neuman Systems Model.

Norwalk, CT Appleton & Lange, p.26)

38

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

functioning and which include the ego

and self concept;

the sociocultural variable refers to

those social and cultural factors which

influence the life of the child and his

interaction with others. The cultural

background of the child and the

life-style of his fam ily will often

determine his reaction to unfamiliar

situations such as hospitalization.

According to Walters (1983: 56) the

n u rs e

m u st g u a rd

a g a in s t

ethnocentricity and should consider

the chents cultural views of health and

illness before attempting to plan or

implement nursing care. She further

states that "... open recognition and

c o n s id e r a tio n fo r in d iv id u a l

differences will help to foster interest,

respect, and compliance" and avoiding

cultural contradictions will eliminate

confusion about differen t health

practices (Walters 1983: 59).

th e cognitive variable involves the

processes of thought, understanding

and learning; and

the spiritual variable refers to those

factors of ethical, moral and religious

origin which impinge on the preschool

child through the influence of the

values and beliefs of his family (Barry,

1989; Neuman, 1989). Many of the

rituals p ractised at birth, such as

circumcision and baptism, as well as

dietary p rac tic e s, restrictions on

m e d ic a l tr e a tm e n ts , or b e lie fs

regarding illness causation are linked

to the spiritual variable and may have

an effect on health.

The reaction of the child to a stressor is

determined by his defences - which in

Neumans terminology are referred to as

flexible lines of resistance, normal lines of

defense and flexible lines of defence. For

the purposes of this adapted model, only

the flexible lines of resistance and normal

lines of defence are used. Within the

context of this topic a function was not

found for the flexible lines of defence.

The flexible lines of resistance change

c o n tin u a lly as a r e s u lt of th e

interrelationship of the five previously

mentioned variables making up the

basic structure of the child. Factors

like the age or sex of the child, his

p re v io u s

e x p e rie n c e

of

h o sp italizatio n , his sociocultural

background and his developmental or

cognitive stage can all help to protect

him from the stress of hospitalization.

The norm al line of defence is the

childs normal range of responses to

environmental factors. In terms of the

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

hospitalized child this could be the

presence of his parents in the hospital

which buffer him from some of the

stress experienced.

Health definition

In this adapted model, health is viewed as

a state of balance between the person and

his environment which permits optimal

physiological, psychological, cognitive,

sociocultural and spiritual functioning.

The state of the childs health at any

p articu lar tim e is considered to be

c o n tin u a lly ch a n g in g d u e to his

adjustment to environmental stressors

(Neuman 1989: 33).

A description of the environment

Neuman considers that the environment

consists of both internal and external

aspects in a continual state of flux. In

addition, the external environment (or

th a t m ilie u w h ich s u rro u n d s th e

h o sp ita liz e d child com p risin g th e

ph y sical s u rro u n d in g s, e m o tio n a l

environment 2md human resources), is

specifically emphasized. In Neuman

term inology, stressors com prise the

environment and these maybe defined as

"...tension producing stimuli or forces

occurring within both the internal and

external environmental boundaries o f the

client" (Neuman 1989: 70). Stressors can

be c la s s ifie d as in tr a p e r s o n a l,

interpersonal or extrapersonal. Each of

these, as they affect the hospitalized

preschool child, will be described.

Intrapersonal stressors a ris e from

within the child and include factors such

as p ain , b o d ily in tru s io n , fe a r of

mutilation, loss of self-control, the childs

perception of illness and the effects of the

c h ild s p e rs o n a lity an d p a st life

experiences. P arental intrapersonal

stressors would include anxiety and guilt

feelings while sibling stressors would be

aspects like the fear of becoming ill, or

the siblings perception of his parents

relationship to him and his response to

the sick childs illness. If stressors which

impinge on the family as a unit are

considered, then intrafamily stressors

would be all those individual interactions

o c c u rrin g am ong fam ily m em bers

(Neuman 1983: 246^

Interpersonal stressors arise from the

interaction between the child and

other individuals and include such

factors as separation anxiety, parental

anxiety and the unfamiliarity of the

hospital personnel. For the parents or

siblings, interpersonal stressors could

include the childs illness which might

result in the family being unable to

fu n c tio n e ffe c tiv e ly , lack of

information or the exclusion of the

family from care of the sick child.

N eu m an c o n s id e r s in te rfa m ily

stre sso rs to be all those factors

occurring between the family and the

im m ediate en v iro n m en t such as

in te ra c tio n w ith o th e r fam ilies,

co m m u n ity g ro u p s or ag en cies

(Neuman 1983: 246).

E xtrapersonal stressors originate

from outside the individual and he has

no specific control over these. In the

hospital situation these stressors for

the child could include the unfamiliar

environment, the change of routine,

sensory deprivation or overload, and a

lack of play opportunities. For the

p a re n t of the h o sp ita liz ed child

extrapersonal stressors could include

fin a n c ia l c o n c e rn s an d th e

u n fa m ilia rity of th e h o s p ita l

environment and apparatus.

The goal of nursing and a description of

those activities which comprise nursing

Neuman describes the major goal of

nursing as "... helping stabilize both the

individual and the family system, as

c lie n ts, w ithin th e ir environm ent"

(N eum an 1983: 253). This im plies

minimizing the factors which affect

optimal system functioning and reducing

the degree of reaction to a stressor by

strengthening the defence systems and so

ensuring system stability. Neum an

defines the nursing component of her

model as "... keeping the client system

stable through accuracy both in the

assessment of effects and possible effects

of e n v iro n m en ta l stre sso rs and in

assisting client adjustments required for

an optimal wellness level" (Neuman 1989:

34).

Nursing thus consists of intervention

which occurs at the levels of primary,

secondary and tertiary prevention. This is

briefly described hereunder and deak

with in more detail in the next section.

Primary prevention is initiated when

a stressor is suspected or before any

reaction has occurred. During this

stage the c h ild s norm al line of

defence or usual state of wellness is

protected by preventing stress or

reducing risk factors. In the model

adaptation this could include health

m aintenance and prom otion; the

provision of altern ativ es for the

h o s p ita l

c a re

of c h ild re n ;

c o n s id e r a tio n b e in g given to

environmental factors; ensuring that

children are not nursed in adult wards

and prehospital preparation for both

the child and parent. An additional

factor involved in primary prevention

39

is to avoid separating the child from

his parents and to instead encourage

them to remain with him as much as

possible should hospitalization be

inevitable.

Secondary prevention is instituted in

o rd er to stab ilize the child and

strengthen his lines of resistance after

stress symptoms have appeared.

In

terms of the hospitalized child this

would involve providing him with

opportunities to vent his stress by

means of therapeutic play or other

forms of crisis therapy. Free visiting by

parents, siblings and peers should be

encouraged. For the child who is

separated from home, transitional

objects, letters, audio tape-recordings

and photographs could be utilized to

maintain home ties and to decrease

the separation anxiety. In addition,

c o n sisten t care g iv e rs sh o u ld be

provided to prom ote security, and

attention should be given to staffing

ratios and work allocation patterns to

a ch iev e th is g o al. In th o se

circumstances where the nurse is not

able to provide play opportunities, a

ch ild -life p rogram m e sh o u ld be

instituted or a playleader should be

employed.

Tertiary prevention assists the child to

readapt so that a recurrence of the

system disorganization is prevented

and stability is regained. In terms of

the hospitalized preschool child this

would involve aspects such as parental

and staff education. If the child is

severely traumatized as a result of his

hospitalization experience, then he

should be referred for psychological

or psychiatric counselling. For the

parent, tertiary prevention could take

the form of self-help groups and

parental support groups.

A DISCUSSION OF NURSING

INTERVENTION AS IT HAS BEEN

APPLIED IN THE ADAPTED

NEUMAN SYSTEMS MODEL TO

THE CARE OF THE HOSPITALIZED

PRESCHOOL CHILD

Nursing intervention can occur at three

levels. The specific application of

nursing intervention to the care of the

hospitalized preschool child will be

discussed hereunder:

Primary prevention as intervention

The goal of primary prevention is to avoid

contact with a stressor or to strengthen

the childs defence so that a stress

reaction does not occur. During the

primary prevention stage the risk is

known. Prim ary prevention for the

40

preschool child is seen to have a number

of aspects:

The provision of preventative and

promotive health services in th e

com m unity which could initially

impact on the mother in the form of

genetic counselling and antenatal

services; later the baby and young

child are help ed to m aintain or

optimize health and to limit need for

contact with the hospital environment.

Such services would include, amongst

oth ers, a d e q u a te p e ri-n a ta l and

p o s t- n a ta l s e rv ic e s as w ell as

immunization, nutritional, dental,

health screening and health education

services.

Alternative forms of health care are

recommended which will incorporate

the extension of community facilities

and home-care programmes as these

are often less stressful substitutes for

hospital treatment (Dimock 1960:40;

Hales-Tooke 1973:30). The increased

use of day clinics for minor surgical

procedures or treatments could limit

the childs length of exposure to a

strange environm ent. Sinclair &

Whyte advocate the development of

co m m u n ity p a e d ia tr ic n u rsin g

schemes to reduce the length of stay in

hospital for most children and to

p re v e n t

h o s p ita l

a d m issio n

completely for others. These schemes

c o u ld "... p ro v id e b a c k -u p fo r

sh o rt-stay surgery" as well as a

specialist service to children with

chronic or long-term illness (Sinclair

& Whyte 1987: 4). These paediatric

community health nurse specialists,

th ro u g h th e ir c o n tr ib u tio n s to

education, practice and research,

w ould have th e p o te n tia l to

profoundly transform the health and

development of the children of Africa

(Barnes 1987: ii). The extension of day

surgery clinics together with the

provision of a supportive paediatric

community nursing service would

have benefits for all involved. The

nursing scheme could serve as a link

between the home and the clinic and

would be able to provide the necessary

pre- and post-operative preparation,

information and care required.

P re h o sp ita l p a re n ta l a n d ch ild

programmes should be initiated by

n u rse s, p re s c h o o l te a c h e rs ,

psychologists, social workers or other

interested persons to help prepare the

child and his family for an unexpected

hospital admission. Although these

would not be focused on a specific

h o s p ita l or illn e ss, th ey c o u ld

familiarize the child with general

aspects of hospitalization and the

p e rs o n s w o rk in g w ith in th a t

environment. At this level the media

(television, video-tapes and books), as

well as hospital tours, puppet shows or

fantasy play with medical equipment

in the home or preschool environment

could be profitably utilized (Plank,

1964; Whitson, 1972; Altshuler, 1974;

Azarnoff & Regal, 1975; Galligan,

1975; Jolly, 1977; F assler, 1978;

Crocker, 1979; Van Huyssteen 1980;

S c h u lz, R a s c h k e , D e d ric k &

Thompson, 1981; Vogel, 1981; Huth,

1983; Jalongo, 1983; Varni, 1983;

Azarnoff, 1984; Trawick-Sm ith &

Thompson, 1984; Clarke, 1986; Gross,

1986; Alexander, 1988).

Environmental alterations should be

considered so that the hospital milieu

becomes less hostile and threatening

to the young child (Hunt, 1960; Shore,

1965; Lindheim, G laser & Coffin,

1972; Oremland & Oremland, 1973;

Hardgrove & Dawson, 1976; Olds,

1978; Robinson & Clarke, 1980; Jolly,

1981; Olds, 1981; Chan, 1986).

Staff education in th e fo rm of

in-service program m es should be

initiated to educate all those working

with children about the total needs of

the hospitalized child (Robertson,

1970).

Parental presence during the childs

hospitalization should be encouraged

to p re v e n t th e o c c u rr e n c e of

separation anxiety (Bellack 1974). An

infant should be provided with a

mother-substitute if the mother does

not room-in (Ziegler & King, 1982; La

Rossa & Brown, 1982).

Secondary prevention as intervention

In the seco n d ary p rev e n tio n stage

nursing intervention occurs to treat

symptoms which have occurred and

internal and external resources are used

to reduce the reaction and to strengthen

the lines of resistance.

In terms of the preschool child, one

would assume this child had already had

some contact with the health care system

(doctors or specialized investigations) or

was alread y h o sp ita liz e d and as a

consequence was showing some adverse

reaction. The stages of the nursing

process should be utilized to assess the

situation, make a nursing diagnosis, plan

for and then implement some form of

nursing action and evaluate and record

the outcom e (Y ura & W alsh, 1973;

M auksch & David, 1974; Ashworth,

1980; Griffith-Kenney & Christensen,

1986).

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

Secondary p reven tion for the

hospitalized preschool child has the

following possible components:

Crisis therapy should be considered

to allow the child to resolve his fears

and conflicts. Possible interventions

th a t c o u ld p ro v e u s e fu l a re

therapeutic play (Green, 1974; Butler,

Chapm an & Stuible, 1975; Smith,

1977; Clatworthy, 1978; Petrillo &

S an g er 1980; C latw o rth y , 1981;

Pillitteri, 1981; Meer, 1985); filmed

modelling (Melamed & Siegel, 1975;

Melamed, Meyer, Gee & Soule, 1976;

Azarnoff & Woody, 1981; Peterson &

S h ig e to m i, 1981); th e m u tu a l

storytelling technique (Gardner, 1970;

Becker, 1972); stress immunization

(Hardgrove, 1977; Meng & Zastowny,

1982; Poster, 1983; Sarafino, 1986;

Smith, Goodman & Ramsey, 1987)

and sensation-orientated preparation

(Johnson, Kirchoff & Endress, 1976).

With appropriate training it is possible

for the nurse to initiate any of the

above techniques with the child.

Free visiting should be allowed and

encouraged in any paediatric ward to

h e lp r e d u c e th e s tre s s of

hospitalization for the child, as well as

his family. Hospital authorities should

allow visiting by parents, siblings and

p e e rs (S tacey, D e a rd e n , Pill &

Robinson, 1970; American Academy

of Pediatrics, 1971; Jefferies, 1974;

King & Ziegler, 1981).

C on tact with home s h o u ld be

encouraged for those children whose

family are not able to visit due to

g e o g ra p h ic a l d ista n c e or o th e r

factors. (Chadwick, Pflederer & Ray,

1978; Marlow & Redding, 1988).

The child should be allowed to bring

transitional objects from home and

these could include any items that are

"special" to the child like blankets,

toys, dummies or any other object

which provides security to the child.

Parents should be discouraged from

trying to wean their children from

dummies or drinking bottles during

this period. To help the child to deal

w ith th e fe a r of a b a n d o n m e n t,

parents should be advised to leave

transitional objects from home, such

as the mothers handbag or scarf, so

that the child knows she will return.

In order to reduce anxiety in the young

child and to be able to provide the

child with individualized attention, he

should be exposed to as few strange

people as possible. For this reason a

consistent caregiver is recommended

w hich w ill involve th e " p a tie n t

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

allocation" system being used instead

of th e "task a llo c atio n " system

(Hales-Tooke, 1973; Weller, 1980;

Pillitteri, 1981). In addition, there

must be adequate staff provision so

that the nurse is able to give sufficient

attention to each child under her care

(Cleary, 1979).

In situations where the nurse is not

able to provide play opportunities for

her paediatric patients, the hospital

authorities should consider instituting

a child-life programme or employing

a playleader w ho can p ro v id e

a d e q u a te

re c r e a tio n a l

and

therapeutic play activities (Stacey et

al., 1970; Azarnoff & Flegal, 1975;

Hart, 1976; Hall, 1977; Hall & Stacey,

1979).

The child should be helped to meet his

needs for control by offering him

choices, for example with foods or

toys, whenever possible. The older

preschool child could be allowed to

participate in his own personal care or

nursing treatments.

Additional strategies which may be used

to allow the child to regain some control

over what is happening to him include

continuing with those rituals and routines

to which the child is accustomed at home

as well as allowing him as much physical

a c tiv ity a n d e x p lo ra tio n of th e

environment as his condition permits. He

should also be allowed to wear his own

pyjamas.

Parental participation in care should

be encouraged, both in personal care

activities as well as in providing

comfort and support during medical

and nursing procedures or treatments

(Bellack, 1974). In order to promote

an a tm o s p h e re co n d u c iv e to

mothering, privacy and a comfortable

chair should be available at each bed

or cot. If parents are not able to

room-in with their child then they

should be advised to be available at the

childs normal bedtime as this is a time

w hen th e c h ild is p a rtic u la rly

vulnerable. The parents should be

encouraged to continue with the

childs usual bedtime rituals so that the

unfamiliarity of the environment is

reduced. Parents should also be given

the opportunity to talk openly to staff

about their childs illness so that the

stress that they are experiencing is

acknowledged.

Children who are confined to bed

m ust re c e iv e a d e q u a te sensory

stimulation (Lindsay, 1981; Chaze &

L u d in g to n -H o e , 1984). Y oung

children should be provided with

opportunities for visual exploration

(mobiles, mirrors, toys, pictures and

books); tactile stimulation through

cuddling, stroking and holding and

auditory stimulation through talking

and music. Physical mobility should be

perm itted provided there are no

medical reasons to restrict this. If the

child is being exposed to excessive

stim u la tio n th en this should be

decreased in whatever areas possible.

Nursing care should be so organized

that definite quiet periods are allowed

for rest or sleep.

Tertiary prevention as intervention

Tertiary prevention is implemented when

the child has regained some degree of

system sta b ility as a resu lt of the

secondary prevention m easures that

were instituted. The goal of tertiary

prevention is to maintain reconstitution

by preventing additional reactions to

stressors or regression from the childs

p resent level of stability. The ideal

outcome of intervention at this stage is

"... turning the stressful situation and the

p ro b le m -s o lv in g a c tiv itie s in to

growth-producing experiences ... which

... build strength, confidence and coping

capacity to handle future stresses or

crises successfully and independently".

To achieve this, tertiary prevention

usually necessitates a team approach with

other "helping professions" (Peachey

1981: 278).

Tertiary prevention as intervention, has

b e e n in te r p r e te d in term s of th e

hospitalized child, to have the following

components:

Staff education should be instituted at

an in-service level to educate all staff

members who have contact with the

child regarding the stress to which he

is e x p o se d to in th e h o s p ita l

e n v iro n m en t. T h ese in -serv ice

programmes should include aspects

like child comm unication, parent

com m unication, p re p a ra tio n for

medical and nursing procedures and

how to include the family in the care of

the ill child. These courses should

s tre s s th a t in d iv id u a liz e d a n d

humanistic nursing care of children

r e q u ir e s k n o w led g e of c u rre n t

theories of child development, family

d ev elo p m en t and the effects of

hospitalization on children. Nurses

working in paediatric units must be

made to realize that the child should

be e m p h a size d ra th e r th an th e

attainm ent of psychom otor skills

(Folan 1983: 208-215).

41

Staff communication in the hospital is

im p o rta n t and re g u la r m eetings

should be h eld to discuss those

policies and procedures which impact

negatively on the childs experience of

hospitalization. In addition attempts

sh o u ld

be

m ade,

on

an

interdisciplinary level, to discuss the

creation or institution of programmes

(p read m issio n or in -hospital) to

alleviate the stress of hospitalization

(Schreier 1980: 52).

factors such as his developmental level,

age, sex, cognitive stage and family

background. This adaptation of the

Neuman Systems Model is one attempt to

demonstrate how nursing interventions

can be utilized to help red u ce the

in tr a p e r s o n a l, in te r p e r s o n a l an d

extrapersonal stressors that affect the

hospitalized preschool child and his

family.

REFERENCES

Parental education is important so

that the parents are made aware of the

possible symptoms of regression that

the child m ight exhibit after his

discharge from hospital. Parents

should be advised to accept regression

as a healthy reaction to stress and

should be reassured that the child will

return to normal if he is treated with

consistency and love (Hymovich,

1976; Asen-Rudbarg Vardaro, 1978;

D roske, 1978; G elderblom , 1981;

V estal, 1981; S ch ep p , 1991). In

addition, parents should be educated

regarding techniques which they can

use to assist the young child to cope

with stress (Honig, 1986). Any nurse

who is initiating a parental education

session should consider the following

factors: the cultural background of the

parents, their fluency in the language

of tuition, their previous level of

knowledge, their anxiety level and the

existence of any m isconceptions

regarding th eir ch ild s illness or

treatment.

The nurse should refer the child to

p sy c h o lo g ic a l o r p s y c h ia tric

counselling services should he show

any serious behavioural disorders as a

result of his hospitalization.

Parents should be supported during

their childs hospitalization and given

the opportunity to express their needs

and em otions. P arents should be

referred to parental support groups

and self-help groups who will help

them to resolve problems when help is

unavailable within the traditional

health structures (Skovholt, 1974;

Trainor, 1983; Marlow & Redding,

1988). Likewise, help in the form of

individual counselling or self-help

groups should be obtained for any

siblings who are experiencing stress so

th a t th e ir c o p in g a b ilitie s a re

strengthened.

ALEXANDER, S. (1988). Puppets as

a teaching tool. Nursing RSA, 3(9):

24-26.

ALTSHULER, A. (1974). Books that

help children deal with a hospital

experience. Rockville, MD: U.S.

Department of Health, Education and

Welfare.

A M E R IC A N

ACADEM Y

OF

P E D IA T R IC S . (1971). C a re of

children in hospitals. 2nd edition.

Evanston, IL: American Academy of

Pediatrics.

A SEN -R U D B A R G V A R D A R O , J.

(1978). Preadm ission anxiety and

mother-child relationships. Journal of

the A ssociation for the C are of

Children in Hospitals, 7(2): 8-15.

ASHWORTH, P. (1980). Problems and

solutions. Nursing M irror. 151(12):

34-36.

A Z A R N O F F, P. and F L E G A L , S.

(1975). A paediatric play program.

Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

AZARNOFF, P. & HARDGROVE, C.

(Eds.) (1981). The family in child

health care. New York: John Wiley &

Sons.

A Z A R N O FF, P. & W O O D Y , P.D.

(1981). Preparation of children for

hospitalization in acute care hospitals

in the U n ited S tates. Pediatrics,

68(3): 361-368.

A Z A R N O FF, P. (1984). P rep arin g

c h ild re n fo r th e s tr e s s of

hospitalization. R esident & Staff

Physician, 30(4): 56-59.

BARNES, C.M. (Ed.) (1987). Recent

advances in nursing: nursing care of

c h ild re n in h e a lth a n d illn e ss.

London: Churchill-Livingstone.

CONCLUSION

The manner in which a child copes with

illness and hospitalization is significantly

influenced by stressors which affect him

in varying degrees, dependant upon

42

BARRY, P.D. (1989). Psychosocial

nursing assessment and intervention:

care of the physically ill person. 2nd

edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

BEAL, J.A. (Ed.) (1983). Issues and

advanced p ra c tic e in p a e d ia tric

nursing. Reston: Reston Publishing

Company.

BECKER, R.D.C. (1972). Therapeutic

approaches to psychopathological

r e a c tio n s to h o s p ita liz a tio n .

I n te r n a tio n a l J o u r n a l o f C hild

Psychotherapy. 1: 65-97.

BELLACK, J.P. (1974). Helping a child

c o p e w ith th e s tr e s s of injury.

American Journal of Nursing, 74(8):

1491-1494.

BROWNING, M.H. & MINEHAN, P.L.

(1974). T he n u rsin g p ro c e ss in

p ra c tic e . New Y ork: A m erican

Journal of Nursing Company.

B U T L E R , A ., C H A P M A N , J. &

STUIBLE, M. (1975). Childs play is

therapy. Canadian Nurse, 71(12):

35-37.

CA STLED IN E, G. (1986). A stress

adaptation model. In Kershaw, B. &

Salvage, J. (Eds.) Models for Nursing.

New York: John Wiley.

CHADWICK, B.J., PFLEDERER, D. &

RAY, M.A. (1978). Maintaining the

h o s p ita liz e d c h ild s hom e ties.

American Journal of Nursing. 78(8):

1361-1362.

CHAN, J.M . (1986). Environm ental

c o n sid eratio n s in pro m o tin g the

adjustment of children to the health

care setting. Interface. 11(2): 6-12.

CHAZE, B.A. & LUDINGTON-HOE,

S.M. (1984). Sensory stimulation in

the N ICU . A m erican Journal of

Nursing, 84(1): 68-71.

CLARKE, D.L. (1986). The value of play

for convalescing children. In McKee,

J.S. (Ed.) Play: Working partner of

growth. Wheaton, MD: Association

fo r

C h ild h o o d

E d u c a tio n

International.

CLA TW O R TH Y , S.M. (1978). The

effect of th erap eu tic play on the

anxiety behaviors of hospitalized

c h ild re n . D .E d . th e s is , B o sto n

University School of Education.

C L A T W O R T H Y , S.M . (1981).

T h e r a p e u tic p lay : e ffe c ts on

hospitalized children. Journal of the

Association for the Care of Children

in Hospital. 9(4): 108-113.

CLEMENTS, I.W. & ROBERTS, F.B.

(E d s.) (1983). Fam ily health : A

theoretical approach to nursing care.

New York: John Wiley.

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

CROCKER, E. (1979). Hospital books

for children. Canadian Nurse. 75(11):

33.

HALES-TOOKE, A. (1973). Children in

hospital: the parents view. London:

Priory Press.

CROSS, J.R. (1990). Betty Neuman. In

George, J.B. (Ed.) Nursing theories:

The base for professional nursing

practice. 3rd edition. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

HALL, D.J. (1977). Social relations and

innovation: Changing the state of play

in hospitals. London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

DIMOCK, H.G. (1960). The child in

hospital: a study of his emotional and

social well-being. Philadelphia: F.A.

Davis.

D R O S K E , S.C. (1978). C h ild re n s

b e h a v io ra l c h a n g e s fo llo w in g

hospitalization: have we prepared the

parents? Jo u rn a l of the C are of

Children in H ospital 7(2): 3-7.

FASSLER.J. (1978). Helping children

cope. New York: Free Press.

FITZPATRICK, J.J. & WHALL, A.L.

(1983). Conceptual models of nursing:

Analysis and application. Bowie,

MD: R.J. Brady.

FOLAN, M.T. (1983). Development of

teaching experiences that emphasize

the child. In Beal, J.A. (Ed.) Issues

and advanced practice in paediatric

nursing. Reston: Reston Publishing

Company.

GALLIGAN, A.C. fl975). Books for the

hospitalized child. American Journal

of Nursing. 75(12): 2164-2166.

GARDNER, R.A. (1970). The mutual

storytelling technique; use in the

tr e a tm e n t of a c h ild w ith

post-traum atic neurosis. American

Journal of Psychotherapy. 24:419-439.

HALL, D.J. & STACEY, M. (1979).

Beyond separation: Further studies of

c h ild re n in h o s p ita l. L o n d o n :

Routledge & Kegan Paul.

H A R D G R O V E, C.B. & DAWSON,

R.B. (1976). Ideas, A to Z, for

p e rs o n a liz in g p a e d ia tr ic u n its.

Nursing 76. 6(4): 57-65.

LaR O SSA , M .M . & BROW N, J.V.

(1982). Foster grandmothers in the

premature nursery. American Journal

of Nursing. 82(12): 1834-1835.

HARDGROVE, C. (1977). Emotional

inoculation: the 3 Rs of preparation.

Journal of the Care of Children in

Hospital. 5(4): 17-19.

L IN D H E IM , R. G LASER, H .H . &

C O F F IN , C. (1972 ). C h an g in g

hospital environments for children.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

HART, D. (1976). The role of the play

leader in the hospital. Australasian

Nurses Journal. 5(4): 30-32.

HAW KINS, J.W. (1983). H istorical

development of models of nursing

practice. In Thibodeau, J.A. Nursing

m odels: Analysis and evaluation.

Belmont: Wadsworth Inc.

HONIG, A.S. (1986). Stress and coping

in children. (Part 1). Young Children,

41(4): 51-63.

HONIG, A.S. (1986). Stress and coping

in children. (Part 2). Young Children.

41(5): 47-59.

HUNT, W.D. (1960). Hospitals, clinics

and health centres: An architectural

record book. New York: McGraw

Hill.

HU TH, M.M. (1983). Guidelines for

conducting hospital tours with early

sc h o o l-a g e c h ild re n . Paediatric

Nursing. 9(6): 414-415 & 430-431.

G E L L E R T , E . (E d .)

(1978).

Psychosocial aspects of paediatric

care. New York: Grune & Stratton.

HYMOVICH, D.P. (1976). Parents of

sick children: their needs and tasks.

Paediatric Nursing. 2: 9-13.

GEORGE, J.B. (Ed.) (1990). Nursing

theories: the base for professional

n u rsin g p r a c tic e . 3 rd e d itio n .

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

JALONGO, M.R. (1983). Using crisis

oriented books with young children.

Young Children. 38(5): 29-36.

JEFFERIES, P.M. (1974). Free visiting

for children. Paediatric Nursing Care.

London: Nursing Times Publication.

G R IF F IT H -K E N N E Y , J.W . &

CHRISTENSEN, P.J. (1986). Nursing

jrocess: app licatio n of theories,

rameworks and models. 2nd edition.

St Louis: C.V. Mosby.

JOHNSON, J.E., KIRCHHOFF, K.T. &

E N D R E SS, M.P. (1976). E asing

childrens fright during health care

procedures. Am erican Journal of

M atern al-C h ild Nursing.

1(4):

206-210.

GROSS, S. (1986). Paediatric tours of

h o sp ita ls: p o sitiv e or n egative?

American Journal of Maternal-Child

Nursing. 11(5): 336-338.

JOLLY, J. (1977). How to be in hospital

without being frightened. Nursing

Times. 72(48): 1887-1888.

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

KERSHAW, B. & SALVAGE, J. (Eds.)

(1986). M odels for nursing. New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

KING, J. & ZIEGLER, S. (1981). The

effects of hospitalization on childrens

behaviour: a review of the literature.

Journal of the Association for the

Care of Children in Hospital. 10(1):

20-28.

G E L D E R B L O M , I.L . (1981). D ie

reaksies van ouers en kinders t.o.v.

h o s p ita lis a s ie

en

m e d ie se

b eh an d elin g . Geneeskunde. 23:

117-121.

GREEN, C.S. (1974). Understanding

childrens needs through therapeutic

play. Nursing 74,4(10): 31-32.

JOLLY, J. (1981). The other side of

paediatrics. London: Macmillan.

LINDSAY, K.E. (1981). The value of

m usic fo r h o s p ita liz e d in fa n ts.

Journal of the Association for the

Care of Children in Hospitals. 9(4):

104-107.

LOUIS, M. & KOERTVELYESSY, A.

(1989). The Neuman model in nursing

research. In Neuman, B. The Neuman

Systems Model. 2nd edition. Norwalk,

CT: Appleton & Lange.

MARLOW, D.R. & REDDING B.A.

(1988). T e x tb o o k of p a e d ia tric

nursing. 6th edition. Philadelphia:

W.B. Saunders.

M A U K SC H , LG. & D A VID, M.L.

(1974). Prescription for survival. In

Browning, M.H. & Minehan, P.L.

The nursing process in practice. New

York: American Journal of Nursing

Company.

McKEE, J.S. (Ed.) (1986). Play: working

partner of growth. Wheaton, MD;

Association for Childhood Education

International.

M EER, P.A. (1985). Using play therapy

in o u tp atie n t settings. A m erican

Journa of Maternal-Child Nursing,

10(6): 378-380.

M ELA M ED , B.G. & SIEG EL, L.J.

(1975). R e d u c tio n of anxiety in

children facing hospitalization and

surgery by use of filmed modelling.

J o u rn a l of C o n su ltin g C lin ic a l

Psychology. 43(4): 511-521.

MELAMED, B.G., MEYER, R., GEE,

C. & S O U L E , L. (1976). T he

in flu e n c e o f tim e and ty p e of

preparation on childrens adjustment

to H o sp ita liz a tio n . J o u rn a l of

Paediatric Psychology. 1(4); 31-37.

MENG, A.L. & ZASTOWNY, T. (1982).

Preparation for hospitalization: A

stress inoculation training program

43

for parents and children. American

Journal of Maternal-Child Nursing.

11(2): 87-94.

NEUM AN, B. (1982). The Neuman

System s M o del: A p p lic a tio n to

nursing e d u c atio n and p rac tic e .

Norwalk, CT: A ppleton-C enturyCrofts.

N E U M A N , B. (1 9 8 3 ). F am ily

intervention using the Betty Neuman

H e a lth -c a re System s M o d el. In

C lem ents, I.W. & R o b e rts, F.B.

Family health: A theoretical approach

to nursing care. New York: John

Wiley & Sons.

NEUM AN, B. (1989). The Neum an

Systems Model. 2nd edition. Norwalk,

CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

OLDS, A .R . (1978). Psychological

considerations in hum anizing the

physical environment of paediatric

outpatient and hospital settings. In

Gellert E. (Ed.) Psychosocial aspects

of paediatric care. New York: Grune

& Stratton.

American Journal of Maternal-Child

Nursing. 12(1): 120-134.

R O B ER TSO N , J. (1970). Young

c h ild re n in h o s p ita l. L o n d o n :

Tavistock.

ROBINSON, G.C. & CLARKE, H.F.

(Eds.) (1980). The hospital care of

children: a review of contemporary

issues. New York: Oxford University

Press.

SARAFINO, E.P. (1986). The fears of

childhood: a guide to recognizing and

reducing fearful states in children.

New York: Human Sciences Press.

S C H E P P , K .G . (1 9 9 1 ). F a c to r s

influencing the coping effo rt of

m others of hospitalized children.

Nursing Research. 40(1): 42-46.

SCHREIER, A. (1980). Preparing young

c h ild re n fo r h o s p ita lis a tio n .

Preschool Years. 10: 48-53.

OLDS, A.R. (1981). Humanizing the

p a e d ia tric hospital environm ent.

Hospital Adm inistration Currents,

25(1): 1-6.

S C H U L Z , J.B ., R A S C H K E , D .,

DEDRICK, C & THOMPSON, M.

(1981). The effects of a preoperational

puppet show on anxiety levels of

hospitalized children. Journal of the

Association for the Care of Children

in Hospital. 9(4): 118-121.

OREMLAND, E.K. & OREMLAND,

J.D . (1 9 7 3 ). T h e e ffe c ts of

hospitalization on children: models

for their care. Springfield, IL: Charles

C. Thomas.

SHORE, M.F. (Ed.) (1965). "Red is the

colour of hurting": planning for

children in the hospital. Betheseda,

MA: National Institute of M ental

Health.

PARKER, S.E. (1983). Paediatric care: a

guide for patient education. Norwalk,

CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

SINCLAIR, H. & WHYTE, D. (1987).

Perspectives on community care for

children. In Barnes, C.M. (Ed.)

Recent advances in nursing: Nursing

care of children in health and illness.

London: Churchill-Livingstone.

PEA CH EY , C.R. (1981). M anaging

stress: family crisis intervention. In

Tackett, J.J.M. & Hunsberger, M.

Family centered care of children and

adolescents: nursing concepts in child

health. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

PETERSON, L. & SHIGETOM I, C.

(1981). The use of coping techniques

to minimize the anxiety in hospitalized

children. Behavior Therapy, 12:1-14.

PETRILLO, M. & SANGER, S. (1980).

E m o tio n a l c a re of h o s p ita liz e d

children: an environmental approach.

2nd e d itio n . P h ila d e lp h ia : J.B .

Lippincott.

PILLITTERI, A. (1981). Child health

nursing: care of the growing family.

2nd edition. Boston: Little, Brown.

PLA N K , E . (1964). W orking w ith

children in hospitals: a guide for the

p r o fe s s io n a l te a m .

London:

Tavistock.

PO STER,

E.

(1 9 8 3 ).

S tre s s

immunization; techniques to help

children cope with hospitalization.

44

SKOVHOLT, T.M. (1974). The client as

h e lp e r: a m ean s to p ro m o te

psychological growth. Counselhng

Psychologist. 4(3): 58-64.

SMITH, L.F. (1977). An experiment with

play therapy. American Journal of

Nursing. 77(12): 1963-1965.

SMITH, M.J., GOOD M AN, J.A. &

RAMSEY, N.L. (1987). Child and

family: Concepts of nursing practice.

2nd edition. New York: McGrawHill.

STACEY, M., DEARDEN, R., PILL, R.

& ROBINSON, D. (1970). Hospitals,

children and their families. London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul.

TACKETT, J.J.M. & HUNSBERGER,

M. (1981). Family centered care of

children and adolescents: nursing

concepts in child health. Philadelphia:

W.B. Saunders.

TH IBODEAU , J.A. (1983). Nursing

m odels: analysis and evaluation.

Belmont: Wadsworth Inc.

T R A IN O R , M.G. (1983). Self-Help

groups as a resource for individual

clients and families. In Clements, I.M.

& Roberts, F.B. (Eds.) Family health:

a theoretical approach to nursing

care. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

TRAWICK-SMITH, J. & THOMPSON,

R .H . (1 9 8 4 ). P r e p a r in g young

children for h o sp ital^tion. Young

Children. 39(5): 57-63.

VAN HUYSSTEEN, M. (1980). Die

kind in die hospitaal: verpleegster praat en speel met hom! Curationis.

3(2): 16-19.

VARNI, J.W. (1983). Clinical behavioral

ediatrics: A n inter- disciplinary

iobehavioral approach. New York:

Pergamon.

VESTAL, K.W. (Ed.) (1981). Paediatric

critical care nursing. New York: John

Wiley.

VOGEL, J.B. (1981). Child life and play

program s. In V estal, K.W. (Ed.)

Paediatric critical care nursing. New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

WALTERS, C.R. (1983). Cultural and

environmental influences on health

teaching. In Parker, S.E. Paediatric

care: a ^ i d e for patient education.

Norwalk, CT. A ppleton-C enturyCrofts,

WELLER, B.F. (1980). Helping sick

children play. London: Balliere

Tindall.

W H A L L , A .L . (1983). T h e B ettv

Neuman Health Care System Model.

In Fitzpatrick, J.J. & Whall, A.L.

C o n c e p tu a l m o d els of n ursing:

analysis and application. Bowie, MD:

R.J. Brady.

WHITSON, B.J. (1972). The puppet

treatm ent in pediatrics. American

Journal of Nursing. 72(9): 1612-1614.

YURA, H. & WALSH, M.B. (1973). The

nursing process: assessing, planning,

im p lem e n tin g , e v a lu a tin g . 2nd

e d itio n . New Y ork: A p p le to n Century-Crofts.

Z IE G L E R , S. & KING , J. (1982).

Evaluating the observable effects of

foster grandparents on hospitalized

children. Public H ealth Reports,

97(6): 550-557.

JOAN PENELOPE ORR

MA Nursing Science (UNISA)

H.E.D. (Preprimary) (UNISA)

Hons. BA CUR (UNISA)

B.Soc.Sc. (Nursing) (U.N.)

Lecturer-Department of Didactics,

University of South Africa

Curationis, Vol. 16, No. 3,1993

You might also like

- Anchored: How to Befriend Your Nervous System Using Polyvagal TheoryFrom EverandAnchored: How to Befriend Your Nervous System Using Polyvagal TheoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Betty Neuman's Systems Model Nursing Theory ExplainedDocument16 pagesBetty Neuman's Systems Model Nursing Theory ExplainedAnnapurna Dangeti100% (2)

- RGO AbPsy Handout2019 PDFDocument24 pagesRGO AbPsy Handout2019 PDFJoshuamadelDelantar100% (3)

- Betty Neuman (System Model) 2007Document16 pagesBetty Neuman (System Model) 2007ladylisette100% (1)

- Oet Winner Online OetDocument2 pagesOet Winner Online OetSibi Johny56% (9)

- Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (And Subscales) (Rcads)Document6 pagesRevised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (And Subscales) (Rcads)e_nov78No ratings yet

- The System ModelDocument8 pagesThe System ModelDebbieNo ratings yet

- Neumans TheoryDocument26 pagesNeumans Theoryimam trisutrisnoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Theory: Betty Neuman's: By: Harpreet Kaur M.Sc. 1 YearDocument34 pagesNursing Theory: Betty Neuman's: By: Harpreet Kaur M.Sc. 1 YearSimran JosanNo ratings yet

- NSG TheoriesDocument103 pagesNSG TheoriesPriya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's System ModelDocument6 pagesBetty Neuman's System ModelCarlo De Vera100% (1)

- Betty Neuman's System ModelDocument32 pagesBetty Neuman's System ModelMarjodi AlexizNo ratings yet

- Module 8 2023Document28 pagesModule 8 2023jamsineNo ratings yet

- Framework Analysis - PatalitaDocument2 pagesFramework Analysis - PatalitaAxe Pulse PatalitaNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument5 pagesBetty NeumanErylshey IllarandaveyNo ratings yet

- NTRODUCTIONDocument8 pagesNTRODUCTIONEzHam Decampong SangcopanNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman: BY: Sri Nur Yanti Margolang NPM: 12.11.086Document11 pagesBetty Neuman: BY: Sri Nur Yanti Margolang NPM: 12.11.086elfrika gintingNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman Health Care System Model ExplainedDocument13 pagesBetty Neuman Health Care System Model ExplainedJoshua BalladNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's Systems Model ExplainedDocument5 pagesBetty Neuman's Systems Model ExplainedNicole Allyson DomingoNo ratings yet

- TFN Handout Nos. 5-7 - WEEK3Document25 pagesTFN Handout Nos. 5-7 - WEEK3JULIANNE BAYHONNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman'S System ModelDocument6 pagesBetty Neuman'S System ModelSimon Josan100% (1)

- Application of Betty NeumanDocument17 pagesApplication of Betty NeumanAnusha Verghese100% (2)

- Betty Neuman ReportDocument5 pagesBetty Neuman ReportKathleen BatallerNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument10 pagesBetty NeumanDanica Mae PepitoNo ratings yet

- ER Environment's Impact on Patients and ProvidersDocument7 pagesER Environment's Impact on Patients and ProvidersdickiechanNo ratings yet

- TheoristsDocument5 pagesTheoristsJuilliard VergaraNo ratings yet

- The Neuman Systems Model - Founder and Key ConceptsDocument14 pagesThe Neuman Systems Model - Founder and Key ConceptsSanthosh.S.U100% (2)

- Nursing Research - 1972.: Betty Neuman's System ModelDocument7 pagesNursing Research - 1972.: Betty Neuman's System ModelYousef KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's Systems Model ExplainedDocument8 pagesBetty Neuman's Systems Model ExplainedAaroma BaghNo ratings yet

- NURSING CONCEPTS Exam GuideDocument24 pagesNURSING CONCEPTS Exam Guide2016114427No ratings yet

- Nursing Theories: I. Nightingale'S Environmental TheoryDocument27 pagesNursing Theories: I. Nightingale'S Environmental TheoryCnette S. LumboNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's System ModelDocument10 pagesBetty Neuman's System ModelKara Kristine Tuano NarismaNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument25 pagesBetty NeumanCarry Ann JunturaNo ratings yet

- Application of Betty NeumanDocument22 pagesApplication of Betty NeumanMary Janet Pinili100% (2)

- Neuman PresentationDocument50 pagesNeuman PresentationJea GeeNo ratings yet

- Systems Model: Betty NeumanDocument31 pagesSystems Model: Betty NeumanHoney Lax100% (2)

- Additional Conceptual ModelsDocument54 pagesAdditional Conceptual Modelsgmunoz230000000945No ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's Nursing TheoryDocument3 pagesBetty Neuman's Nursing TheoryKrizzanne Flores100% (1)

- Assignment No. 1: Module 1: Framework For Maternal and Child Health NursingDocument11 pagesAssignment No. 1: Module 1: Framework For Maternal and Child Health NursingAna LuisaNo ratings yet

- FNightingale TheoryDocument11 pagesFNightingale TheoryFlorinel B. LACATANNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman'S Theory: Introduction About TheoristDocument11 pagesBetty Neuman'S Theory: Introduction About TheoristRenita ChrisNo ratings yet

- Person VariablesDocument3 pagesPerson VariablesRasmeow_TheMus_3383No ratings yet

- TFN ReportDocument36 pagesTFN ReportHanna BaddiriNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's System Model ExplainedDocument4 pagesBetty Neuman's System Model ExplainedTim AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's System ModelDocument7 pagesBetty Neuman's System ModelNi Kadek Sri WidiyantiNo ratings yet

- Neuman TheoryDocument10 pagesNeuman Theorypreeti19987No ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument4 pagesBetty NeumanChristiane with an ENo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman Systems ModelDocument18 pagesBetty Neuman Systems ModelMin Min50% (2)

- Betty NeumanDocument25 pagesBetty NeumanGREESHMA RAJUNo ratings yet

- Betty Nauman System ModelDocument4 pagesBetty Nauman System ModelVic DwayneNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman: Systems Theory in Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesBetty Neuman: Systems Theory in Nursing PracticeJeremy CollamarNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument20 pagesBetty NeumanJamie Joy CapuyanNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument27 pagesBetty NeumanOliver Grey OcamposNo ratings yet

- Theoretical approaches to analyzing client systemsDocument14 pagesTheoretical approaches to analyzing client systemsDominic John AseoNo ratings yet

- Module 9 Betty NeumanDocument5 pagesModule 9 Betty NeumanalexandratrixiabNo ratings yet

- Betty Neuman's Systems Model overviewDocument6 pagesBetty Neuman's Systems Model overviewElaine Frances IlloNo ratings yet

- Neuman's System ModeDocument5 pagesNeuman's System ModerJNo ratings yet

- Betty NeumanDocument18 pagesBetty NeumanBryan AmoresNo ratings yet

- LEVEL of STRESS Research ProposalDocument30 pagesLEVEL of STRESS Research ProposalArvin Ian Penaflor100% (2)

- Nur 016 Sas#7Document14 pagesNur 016 Sas#7Jane CamporedondoNo ratings yet

- Children & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsFrom EverandChildren & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Medical Student Well-Being: An Essential GuideFrom EverandMedical Student Well-Being: An Essential GuideDana ZappettiNo ratings yet

- Furosemide: Online AudioDocument4 pagesFurosemide: Online AudioDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Accurate Assessment of Patient Weight - Nursing TimesDocument7 pagesAccurate Assessment of Patient Weight - Nursing TimesDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- A.P.J Abdul Kalam The Visionary of India) On 15: Time Venue: Block - 4, 3Document1 pageA.P.J Abdul Kalam The Visionary of India) On 15: Time Venue: Block - 4, 3Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- CPR Questionnaire - Essential First Aid StepsDocument1 pageCPR Questionnaire - Essential First Aid StepsDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Childhood Obesity in IndiaDocument34 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors of Childhood Obesity in IndiaDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Sharda Hospital Clinical Material Report for October 2016Document1 pageSharda Hospital Clinical Material Report for October 2016Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Ob PDFDocument25 pagesOb PDFDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Appendices Appendices Appendices AppendicesDocument21 pagesAppendices Appendices Appendices AppendicesDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Article 03Document8 pagesArticle 03Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Vit StaDocument6 pagesVit StaDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- 05 N235 33824Document22 pages05 N235 33824Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Research TopicsDocument1 pageResearch TopicsDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- May 2016Document18 pagesMay 2016Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- CPR Questionnaire - Essential First Aid StepsDocument1 pageCPR Questionnaire - Essential First Aid StepsDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- UpdateRequestFormV2 PDFDocument2 pagesUpdateRequestFormV2 PDFeceprinceNo ratings yet

- Records and Registers To Be Maintained at School Level Related To RmsaDocument6 pagesRecords and Registers To Be Maintained at School Level Related To RmsaDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Drug Dosage and IV Rates Calculations PDFDocument6 pagesDrug Dosage and IV Rates Calculations PDFvarmaNo ratings yet

- Appendix I Faculty Evaluation System General InformationDocument11 pagesAppendix I Faculty Evaluation System General InformationDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Clinical RubricDocument5 pagesClinical RubricDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Appendix DDocument5 pagesAppendix DcerisimNo ratings yet

- Trendsandissuesinnursingcompatibilitymode 120712052718 Phpapp01Document24 pagesTrendsandissuesinnursingcompatibilitymode 120712052718 Phpapp01Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Codeofethicsppt 150907030516 Lva1 App6892Document57 pagesCodeofethicsppt 150907030516 Lva1 App6892Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Transportation For ResearchDocument2 pagesTransportation For ResearchDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Care Plan Criteria For Evlauation NOWDocument1 pageCare Plan Criteria For Evlauation NOWDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- STEAM INHALATION RELIEFDocument4 pagesSTEAM INHALATION RELIEFDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1417425593Document10 pagesArticle Wjpps 1417425593Dani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Clinical RubricDocument5 pagesClinical RubricDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- School Stock Register TemplatesDocument10 pagesSchool Stock Register TemplatesDebasis SahaNo ratings yet

- Records and Registers To Be Maintained at School Level Related To RmsaDocument6 pagesRecords and Registers To Be Maintained at School Level Related To RmsaDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Causes and Strategies for Reducing Student AbsenteeismDocument12 pagesCauses and Strategies for Reducing Student AbsenteeismGamas Pura JoseNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Separation AnxietyDocument216 pagesAdolescent Separation AnxietyRimanNo ratings yet

- 7.introduction To Pediatric NursingDocument54 pages7.introduction To Pediatric NursingImelda Verawaty Lumban GaolNo ratings yet

- Testing Anxiety ToolkitDocument150 pagesTesting Anxiety Toolkitالبيضاوي للمعرفة والعلمNo ratings yet

- What To Know About AnxietyDocument6 pagesWhat To Know About AnxietySabah100% (1)

- Nuclear Single Parent Blended Extended Same Sex Binuclear Foster/adoptive Adolescent Dyad Authoritarian/ Dictatorial Authoritative/ DemocraticDocument3 pagesNuclear Single Parent Blended Extended Same Sex Binuclear Foster/adoptive Adolescent Dyad Authoritarian/ Dictatorial Authoritative/ DemocraticCatarina CuandeiraNo ratings yet

- Ansiedad de SeparacionDocument24 pagesAnsiedad de SeparacionFederico AlzugarayNo ratings yet

- Hospitalized Child: Aarti Sharma M.SC (N) 1 YearDocument44 pagesHospitalized Child: Aarti Sharma M.SC (N) 1 YearAarushi Shegal100% (1)

- Depression in Childhood and Adolescence: Clinical Features: Review ArticleDocument8 pagesDepression in Childhood and Adolescence: Clinical Features: Review ArticleManalNo ratings yet

- The Development of Anxiety Disorders: Considering The Contributions of Attachment and Emotion RegulationDocument15 pagesThe Development of Anxiety Disorders: Considering The Contributions of Attachment and Emotion RegulationJohannes CordeNo ratings yet

- Psychology Project FileDocument16 pagesPsychology Project FileAryaman LegendNo ratings yet

- NCM 117: Long Exam 2: Anxiety & Anxiety Disorders Topic OutlineDocument56 pagesNCM 117: Long Exam 2: Anxiety & Anxiety Disorders Topic OutlineLoren SarigumbaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology Review: Andres G. Viana, Deborah C. Beidel, Brian RabianDocument11 pagesClinical Psychology Review: Andres G. Viana, Deborah C. Beidel, Brian RabianGabriela BarrosNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing Bullets Lester R. L. LintaoDocument4 pagesPsychiatric Nursing Bullets Lester R. L. LintaoElizabella Henrietta TanaquilNo ratings yet

- MCN 202 HandoutDocument8 pagesMCN 202 HandoutRogelio Saupan Jr100% (1)

- Chapter 4Document42 pagesChapter 4Athira RaghuNo ratings yet

- The Worry Wars:: Equipping Our Child Clients To Effectively Fight Their FearsDocument16 pagesThe Worry Wars:: Equipping Our Child Clients To Effectively Fight Their FearsAngeliki HoNo ratings yet

- Grief and Mourning BowlbyDocument46 pagesGrief and Mourning BowlbyGabriel LevyNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Child and Adolescent AnxietyDocument57 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Child and Adolescent AnxietyBrian CanoNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Divorce on Children AdjustmentDocument32 pagesThe Influence of Divorce on Children AdjustmentMae Dacer100% (1)

- Cimh Palette of Measures Evaluation Training: Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (Rcads)Document38 pagesCimh Palette of Measures Evaluation Training: Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (Rcads)NasirNo ratings yet

- Patient-Centered Nursing Care of Hospitalized ChildrenDocument55 pagesPatient-Centered Nursing Care of Hospitalized ChildrenJose UringNo ratings yet

- Elective MutismDocument5 pagesElective MutismMAHIMA DASNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Case StudyDocument3 pagesAnxiety Case StudyJennaNo ratings yet

- Stress and Anxiety Parent Presentation-Wooton HS-1-15-19Document36 pagesStress and Anxiety Parent Presentation-Wooton HS-1-15-19Anelise PazNo ratings yet

- 3 Separation ANxiety DisorderDocument3 pages3 Separation ANxiety DisorderMirza ShaplaNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Problems in ChildrenDocument49 pagesBehavioural Problems in ChildrenAshly Nygil100% (1)