Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Supreme Court: Fact-Finding Investigation

Uploaded by

Trishia Fernandez GarciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Supreme Court: Fact-Finding Investigation

Uploaded by

Trishia Fernandez GarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

,{,:::" <<>.

:;'

IM''

\

'"

;

f~,

"t

, ~'t','',""""~

,~e

..

,-....*

?~_!,.~;Y

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

COMMO. LAMBERTO R.

TORRES (RET.),

Petitioner,

Present:

VELASCO, JR., J, Chairperson,

PERALTA,

PEREZ,

REYES, and

J ARDELEZA, JJ.

- versus -

SANDIGANBA YAN (FIRST

DIVISION) and PEOPLE OF

THE PHILIPPINES,

Respondents.

Promulgated:

October 5, 2016

x-----------------------------------------------------~~-~~------x

DECISION

VELASCO, JR., J.:

The Case

Before the Court is a Petition for Certiorari filed under Rule 65 of the

Rules of Court for the annulment of Sandiganbayan Resolutions dated

August 27, 2015 1 and October 28, 2015, 2 with prayer for the issuance of a

status quo order or a temporary restraining order against the Sandiganbayan.

The Facts

From 1991 to 1993, petitioner Commo. Lamberto R. Torres was the

Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff for Logistics under the Flag Officer In

Command of the Philippine Navy. Sometime in July 1991 until June 1992,

the Commission on Audit (COA) conducted a special audit at the

Headquarters of the Philippine Navy (HPN) pertaining to the procurement of

drugs and medicine by emergency mode purchase, among others. On June

18, 1993, the COA issued Special Audit Report No. 92-128, uncovering an

alleged overpricing of medicines at the HPN or its units, and triggering a

Fact-Finding Investigation by the Office of the Ombudsman.

1

Rollo, pp. 170-177. Penned by Associate Justice Rafael R. Lagos and concurred in by Associate

Justices Efren N. De La Cruz and Rodolfo A. Ponferrada.

2

Id. at 196-204.

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

On December 11, 1996, the Office of the Ombudsman commenced a

preliminary investigation against petitioner and several others for Illegal Use

of Public Funds and Violation of Sec. 3 (e) of Republic Act No. (RA) 3019,

otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, docketed as

case number OMB-4-97-0789; and for Violation of Sec. 3 (e) of RA 3019,

docketed as case number OMB-4-97-0790, based on an Affidavit by COA

auditors.

In OMB-4-97-0789, it was alleged that the purchase of additional

drugs and medicines worth 5.56 million was not properly supported and

accounted for, and that additional drugs and medicines purchased were

supposedly not included in the list of drugs and medicines received by the

Supply Accountable Officer of the Hospital for that period. Petitioner was

included as a respondent for being a signatory of the checks involved.

In OMB-4-97-0790, it was alleged that supplies and materials

amounting to 6,663,440.70 were purchased but equipment were delivered,

instead of the items indicated in the purchase orders. Petitioner was

included as a respondent in the OMB-4-97-0790 because he allegedly

recommended the approval of the purchase orders and signed the certificates

of emergency purchases.

These cases, however, were dismissed against petitioner for lack of

probable cause in a Joint Resolution dated March 8, 1999.

A few years after petitioners retirement from the service in 2001,

Tanodbayan Simeon V. Marcelo issued an Internal Memorandum dated

October 11, 2004, recommending a new fact-finding investigation and

preliminary investigation relative to other transactions in other units and

offices of the Philippine Navy. Pursuant to this Internal Memorandum, a

new Affidavit Complaint dated February 22, 2006 was filed by the

Ombudsman against petitioner and several others, this time, for violation of

Sections 3 (e) and (g) of RA 3019, docketed as case number OMB-P-C-060129-A.

Notices of the new preliminary investigation were, however, sent to

petitioners old address in Kawit, Cavite, which he had already vacated in

1980. Thus, petitioner was not informed of the proceedings in the new

preliminary investigation. Unknown to petitioner, eight (8) Informations

were filed by the Ombudsman against him and the other accused before the

Sandiganbayan on August 5, 2011. The first set of Informations, consisting

of four (4) Informations docketed as Crim. Case Nos. SB-11-CRM-0423,

SB-11-CRM-0424, SB-11-CRM-0426 & SB-11-CRM-0427, charged

petitioner and others with violation of Sec. 3 (e) of RA 3019, while the

remaining four (4) Informations, docketed as Crim. Case Nos. SB-11-CRM-

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

0429, SB-11-CRM-0430, SB-11-CRM-0432 & SB-11-CRM-0433, charged

petitioner and others with violation of Sec. 3 (g) of RA 3019.

Petitioner and his co-accused were charged for allegedly giving

unwarranted benefit to several pharmaceutical companies, certifying the

existence of an emergency, and approving the emergency purchase of

overpriced medicines without the proper bidding. It was determined that no

emergency existed and the overpriced items bought were only kept in stock

and were, essentially, over-the-counter drugs.

More particularly, petitioners participation is limited to his issuance

of the Certificates of Emergency Purchase3 that do not indicate the actual

condition obtaining at the time of the purchase to justify the emergency

purchase.

It was only sometime in July 2014, when petitioner was about to

travel to the United States, that he learned of the pending cases before the

Sandiganbayan by virtue of a hold departure order issued against him. Thus,

petitioner filed a Motion for Reduction of Bail with Appearance of Counsel

and Motion for Preliminary Investigation before the Sandiganbayan. With

his motion granted, the proceedings before the Sandiganbayan were deferred

with respect to petitioner and a new preliminary investigation for petitioner

was conducted.

Petitioner was thereafter allowed to file a Counter-Affidavit before the

Office of the Ombudsman, where he prayed for the dismissal of the case on

the ground that his constitutional rights to due process and speedy trial were

violated by the inordinate delay of the case.

In its May 7, 2015 Resolution, the Ombudsman nonetheless resolved

to maintain the Informations filed against petitioner. According to the

Ombudsman, the Affidavit Complaint filed on February 22, 2006, which

resulted in the filing of the August 5, 2011 Informations, was based on a

new investigation. Thus, petitioners inordinate delay argument does not

apply.

Aggrieved, petitioner filed a Motion to Quash the Informations before

the Sandiganbayan, claiming that the Ombudsman had no authority to file

the Informations having conducted the fact-finding investigation and

preliminary investigation for too long, in violation of his rights to a speedy

trial and to due process. According to petitioner, the protracted conduct of

the fact-finding and preliminary investigations lasted for eighteen (18) years.

3

The medicines were purchased from four suppliers, namely: PMS Commercial, Roddensers

Pharmaceuticals, Jerso Marketing, and Gebruder.

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

Hence, it was inordinate and oppressive. Petitioner argued that there was

already this case to speak of pending against him since both sets of factfinding and preliminary investigations conducted by the Ombudsman were

triggered by the same COA report.

The Ombudsman filed its Comment and/or Opposition, arguing that

the preliminary investigations conducted against petitioner in the different

periods (from 1996 to 1999 and from 2006 to 2011) involved different

transactions pursuant to the various findings embodied in the COA Special

Audit Report of 1993. In fact, so the Ombudsman argued, the COA Audit

Report is not a prerequisite to any of its investigation and it may conduct

fact-finding and/or preliminary investigation with or without said report.

In his Reply to the Ombudsmans Comment and/or Opposition,

petitioner insisted, among others, that it still took the Ombudsman another

six (6) years to file the Informations against him.

Ruling of the Sandiganbayan

In a Resolution dated August 27, 2015, the Sandiganbayan denied

petitioners Motion to Quash and sustained the prosecutions position. The

dispositive portion of the Resolution reads:

WHEREFORE, in light of all the foregoing, the Motion to Quash

is hereby DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

Petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration, but the same was

denied in the Sandiganbayan Resolution dated October 28, 2015.

Hence, this petition.

Petitioner asserts that the Sandiganbayan committed grave abuse of

discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction when it denied his Motion to

Quash. He argues that the eight (8) Informations should have been quashed

by the Sandiganbayan considering that the Ombudsman had lost its authority

to file them since petitioners constitutional rights to both the speedy

disposition of cases and to due process were grossly violated by the

inordinate delay of almost 18 years in conducting the fact-finding and

preliminary investigations.

Petitioner further argues that, with the

Ombudsman losing its authority to file the Information, the Sandiganbayan

also lost its jurisdiction over the crimes charged in consequence.

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

In its Comment,4 respondent People of the Philippines prays for the

dismissal of the petition, arguing that petitioners constitutional rights to

speedy disposition of cases and to due process were not violated.

Respondent stresses that, prior to 2006, petitioner had no case to speak of

since it was only in 2007 when the Ombudsman recommended his

indictment. It differentiated COAs audit investigation from 1993 to 1996 as

administrative in nature, from the preliminary investigation from 1996 to

2006 for the cases which were dismissed in favor of petitioner, and from the

preliminary investigation conducted from 2006 to 2011 where petitioners

involvement was established.

Respondent further asserts that the Sandiganbayan did not abuse its

discretion in issuing the assailed Resolution since it was firmly anchored on

a judicious appreciation of the facts and relevant case law.

Thereafter, petitioner filed a Reply to Comment (On Petition for

Certiorari With Application for Status Quo Order and/or Temporary

Restraining Order) asserting that respondent is guilty of hair-splitting by

distinguishing between the fact-finding investigations and preliminary

investigations conducted in 1999 and in 2006 since they both originated

from the June 18, 1993 COA Special Audit Report No. 92-128.

The Issue

Essentially, the principal issue is whether the Sandiganbayan

committed grave abuse of discretion in denying petitioners Motion to

Quash, anchored on the alleged violation of petitioners right to speedy

disposition of cases.

The Courts Ruling

The petition is meritorious.

There is grave abuse of discretion when an act of a court or tribunal is

whimsical, arbitrary, or capricious as to amount to an an evasion of a

positive duty or a virtual refusal to perform a duty enjoined by law or to act

at all in contemplation of law, such as where the power is exercised in an

arbitrary and despotic manner by reason of passion or hostility.5 Grave

abuse of discretion was found in cases where a lower court or tribunal

violates or contravenes the Constitution, the law, or existing jurisprudence.6

4

Rollo, pp. 228-255.

Marie Callo-Claridad v. Philip Ronald P. Esteban and Teodora Alyn Esteban, G.R. No. 191567,

March 20, 2013.

6

Republic of the Philippines v. COCOFED et al., G.R. Nos. 147062-64, December 14, 2001.

5

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

In his Motion to Quash, petitioner invoked Section 3, paragraph (d) of

Rule 117, asserting that the Ombudsman had lost its authority to file the

Informations against him for having conducted the fact-finding and

preliminary investigations too long. He raised a similar argument in the

present petitionthat the Ombudsman had no more authority to file the

Informations since petitioners rights to speedy disposition of cases and to

due process were violated.

In denying the Motion to Quash, the Sandiganbayan ruled:

Ultimately, the results of the 2006 preliminary investigation itself

may not be impugned due to inordinate delay that would rise to the level

of being violative of herein accuseds right to speedy disposition of cases

protected under the Constitution. If ignorance is bliss, the accused had

been spared from the travails of the preliminary investigation which

started in 2006, not like the other respondents who showed up or were

involved therein. By this Courts reckoning it took the OMB-MOLEO

only two (2) years, six (6) months and nineteen (days) [sic] from August

7, 2007 after the issues were joined with the filing of the last counteraffidavit therein and the issuance of the Resolution by Graft Investigator

& Prosecution Officer Marissa S. Bernal on February 25, 2010, which

terminated the preliminary investigation process, finding probable cause.

Furthermore, as requested by the accused, the OMB-Office of the Special

Prosecutor again conducted a new or another preliminary investigation

upon order of this Court, resulting in a new resolution, dated May 7, 2015,

which maintained the informations herein. This was approved by

Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales on May 15, 2015.

This

investigation only took a little over than six (6) months and, therefore,

could not be said to be violative of movants right to a speedy disposition

of his case. There is no showing that movant was made to endure any

vexatious process during the said periods of investigation.

We disagree.

In Isabelo A. Braza v. The Honorable Sandiganbayan (First

Division),7 this Court has laid down the guiding principle in determining

whether the right of an accused to the speedy disposition of cases had been

violated:

Section 16, Article III of the Constitution declares in no uncertain

terms that [A]ll persons shall have the right to a speedy disposition of

their cases before all judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative bodies.

The right to a speedy disposition of a case is deemed violated only when

the proceedings are attended by vexatious, capricious, and oppressive

delays, or when unjustified postponements of the trial are asked for and

secured, or when without cause or justifiable motive, a long period of time

is allowed to elapse without the party having his case tried. The

constitutional guarantee to a speedy disposition of cases is a relative or

flexible concept. It is consistent with delays and depends upon the

7

G.R. No. 195032, February 20, 2013.

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

circumstances. What the Constitution prohibits are unreasonable, arbitrary

and oppressive delays which render rights nugatory.

In Dela Pea v. Sandiganbayan, the Court laid down certain

guidelines to determine whether the right to a speedy disposition has been

violated, as follows:

The concept of speedy disposition is relative or flexible. A

mere mathematical reckoning of the time involved is not sufficient.

Particular regard must be taken of the facts and circumstances

peculiar to each case. Hence, the doctrinal rule is that in the

determination of whether that right has been violated, the factors

that may be considered and balanced are as follows: (1) the length

of the delay; (2) the reasons for the delay; (3) the assertion or

failure to assert such right by the accused; and (4) the

prejudice caused by the delay. (emphasis supplied)

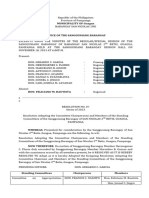

In the present case, the lapse of time in the conduct of the proceedings

is tantamount to a vexatious, capricious, and oppressive delay, which We

find to be in violation of petitioners constitutional right to speedy

disposition of cases. Below is a summary of the proceedings conducted:

DATE

STARTED

On the purchase of drugs Conducted on

and medicines, supplies, July 1 to August

11, 1992.

materials, and equipment

of the HPN for the period

of July 1991 to June 1992.

PARTICULARS

COA Special Audit Report No.

92-128

1. OMB-4-97-0789

(based on Affidavit of

COA Auditors)

OMB-4-97-0790

DATE

ENDED

Issued on

June 18,

1993.

FIRST SET OF INVESTIGATIONS

Case

For the purchase of Complaint filed

additional

drugs

and on December 11, dismissed on

1996.

March 8,

medicines worth Php5.56

1999 due to

Million which were not

lack of

properly supported and

probable

accounted for.

cause.

For the purchase of

supplies and materials

which

were

instead

converted to equipment.

Internal Memorandum issued

by Tanodbayan Simeon V.

Marcelo

Recommending that a

preliminary investigation

be conducted with respect

to the overpricing in the

other offices and units in

the Philippine Navy in

relation to the COA

Special Audit Report No.

92-128.

Issued on

September 30,

2004.

Received by

the

Ombudsman

on October

7, 2004.

Decision

2. OMB-P-C-06-0129-A

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

SECOND SET OF INVESTIGATIONS

Giving

unwarranted Complaint filed

benefit to pharmaceutical on February 22,

2006.

companies, certifying the

existence

of

an

emergency, and approving

the emergency purchase

of overpriced medicines

without

the

proper

bidding.

First

Ombudsman

Resolution

finding

probable

cause issued

on February

25, 2010.

Informations

filed on

August 5,

2011.

OMB-P-C-06-0129-A

(Same case as no. 2)

Conducted pursuant to the

Sandiganbayan Resolution

ordering the Ombudsman

to conduct a preliminary

investigation insofar as

petitioner is concerned.

Sandiganbayan

Resolution

issued on

November 10,

2014.

Second

Ombudsman

Resolution

finding

probable

cause issued

on May 7,

2015.

Respondents claim that the investigation conducted by the COA from

1993 to 1996 was a special audit which is administrative in nature; thus, it

should not be included in counting the number of years lapsed. They further

contend that the preliminary investigations conducted from 1996 to 2006

which pertain to the overpricing of medicines procured through

emergency purchase never included petitioner, but involved other PN

officials, employees, and a private individual. Respondents maintain that it

was only in 2006 that petitioner was implicated in said questionable

transactions. Moreover, the preliminary investigations conducted from 1993

to 1996 against petitioner refer to different transactions, specifically, for

Unaccounted Drugs and Medicines (docketed as OMB-4-97-0789) and for

Conversion (docketed as OMB-4-97-0790), thus, cannot be considered in

determining if his right to speedy disposition of cases had been violated.

While it may be argued that there was a distinction between the two

sets of investigations conducted in 1996 and 2006, such that they pertain to

distinct acts of different personalities, it cannot be denied that the basis for

both sets of investigations emanated from the same COA Special Audit

Report No. 92-128, which was issued as early as June 18, 1993. Thus, the

Ombudsman had more than enough time to review the same and conduct the

necessary investigation while the individuals implicated therein, such as

herein petitioner, were still in active service.

Even assuming that the COA Special Audit Report No. 92-128 was

only turned over to the Ombudsman on December 11, 1996 upon the filing

of the Affidavit of the COA Auditors, still, it had been in the Ombudsmans

possession and had been the subject of their review and scrutiny for at least

Decision

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

eight (8) years before Tanodbayan Marcelo ordered the conduct of a

preliminary investigation, and at least sixteen (16) years before the

Ombudsman found probable cause on February 25, 2010.

Nevertheless, even if we start counting from Tanodbayan Marcelos

issuance of Internal Memorandum on September 30, 2004, there was still at

least six (6) years which lapsed before the Ombudsman issued a Resolution

finding probable cause.

We find it necessary to emphasize that the speedy disposition of cases

covers not only the period within which the preliminary investigation was

conducted, but also all stages to which the accused is subjected, even

including fact-finding investigations conducted prior to the preliminary

investigation proper. We explained in Dansal v. Fernandez, Sr.:8

Initially embodied in Section 16, Article IV of the 1973

Constitution, the aforesaid constitutional provision is one of three

provisions mandating speedier dispensation of justice. It guarantees the

right of all persons to a speedy disposition of their case; includes

within its contemplation the periods before, during and after trial, and

affords broader protection than Section 14(2), which guarantees just the

right to a speedy trial. It is more embracing than the protection under

Article VII, Section 15, which covers only the period after the submission

of the case. The present constitutional provision applies to civil, criminal

and administrative cases. (citations omitted; emphasis supplied)

Considering that the subject transactions were allegedly committed in

1991 and 1992, and the fact-finding and preliminary investigations were

ordered to be conducted by Tanodbayan Marcelo in 2004, the length of time

which lapsed before the Ombudsman was able to resolve the case and

actually file the Informations against petitioner was undeniably long-drawnout.

Any delay in the investigation and prosecution of cases must be duly

justified. The State must prove that the delay in the prosecution was

reasonable, or that the delay was not attributable to it.9 Our discussion in

Coscolluela v. Sandiganbayan (First Division)10 is instructive:

Verily, the Office of the Ombudsman was created under the mantle

of the Constitution, mandated to be the protector of the people and as

such, required to act promptly on complaints filed in any form or manner

against officers and employees of the Government, or of any subdivision,

agency or instrumentality thereof, in order to promote efficient service.

8

G.R. No. 126814, March 2, 2000.

People of the Philippines v. Hon. Sandiganbayan, First Division & Third Division, et al., G.R.

No. 188165, December 11, 2013.

10

G.R. No. 191411, July 15, 2013.

9

Decision

10

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

This great responsibility cannot be simply brushed aside by ineptitude.

Precisely, the Office of the Ombudsman has the inherent duty not only

to carefully go through the particulars of case but also to resolve the

same within the proper length of time. Its dutiful performance should

not only be gauged by the quality of the assessment but also by the

reasonable promptness of its dispensation.

Thus, barring any

extraordinary complication, such as the degree of difficulty of the

questions involved in the case or any event external thereto that effectively

stymied its normal work activity any of which have not been adequately

proven by the prosecution in the case at bar there appears to be no

justifiable basis as to why the Office of the Ombudsman could not have

earlier resolved the preliminary investigation proceedings against the

petitioners. (citation omitted; emphasis supplied)

In the present case, respondents failed to submit any justifiable reason

for the protracted conduct of the investigations and in the issuance of the

resolution finding probable cause. Instead, respondents submit that the

cases subject of this petition involve issues arising from complex

procurement transactions that were conducted in such a way as to conceal

overpricing and other irregularities, by conniving PN officers from different

PN units and private individuals.

A review of the COA Special Audit Report No. 92-128, however,

shows that it clearly enumerated the scope of the audit, the transactions

involved, the scheme employed by the concerned PN officers, and the

possible basis for the filing of a complaint against the individuals

responsible for the overpricing. Respondents argument that the case

involves complex procurement transactions appears to be unsupported by

the facts presented.

There is no question that petitioner asserted his right to a speedy

disposition of cases at the earliest possible time. In his Counter-Affidavit

filed before the Ombudsman during the reinvestigation of the case in 2014,

petitioner had already argued that dismissal of the case is proper because the

long delayed proceedings violated his constitutional right to a speedy

disposition of cases. This shows that petitioner wasted no time to assert his

right to have the cases against him dismissed.

As for the prejudice caused by the delay, respondents claim that no

prejudice was caused to petitioner from the delay in the second set of

investigations because he never participated therein and was actually never

even informed of the proceedings anyway. We cannot agree with this

position. A similar assertion was struck down by this Court in Coscolluela,

to wit:

Lest it be misunderstood, the right to speedy disposition of cases is

not merely hinged towards the objective of spurring dispatch in the

administration of justice but also to prevent the oppression of the citizen

Decision

11

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

by holding a criminal prosecution suspended over him for an indefinite

time. Akin to the right to speedy trial, its salutary objective is to assure

that an innocent person may be free from the anxiety and expense of

litigation or, if otherwise, of having his guilt determined within the

shortest possible time compatible with the presentation and consideration

of whatsoever legitimate defense he may interpose. This looming unrest

as well as the tactical disadvantages carried by the passage of time should

be weighed against the State and in favor of the individual. In the context

of the right to a speedy trial, the Court in Corpuz v. Sandiganbayan

(Corpuz) illumined:

A balancing test of applying societal interests and the rights of

the accused necessarily compels the court to approach speedy trial

cases on an ad hoc basis.

x x x Prejudice should be assessed in the light of the interest of

the defendant that the speedy trial was designed to protect, namely:

to prevent oppressive pre-trial incarceration; to minimize anxiety

and concerns of the accused to trial; and to limit the possibility that

his defense will be impaired. Of these, the most serious is the

last, because the inability of a defendant adequately to prepare

his case skews the fairness of the entire system. There is also

prejudice if the defense witnesses are unable to recall

accurately the events of the distant past. Even if the accused is

not imprisoned prior to trial, he is still disadvantaged by

restraints on his liberty and by living under a cloud of anxiety,

suspicion and often, hostility. His financial resources may be

drained, his association is curtailed, and he is subjected to

public obloquy.

Delay is a two-edge sword. It is the government that bears the

burden of proving its case beyond reasonable doubt. The passage

of time may make it difficult or impossible for the government to

carry its burden. The Constitution and the Rules do not require

impossibilities or extraordinary efforts, diligence or exertion from

courts or the prosecutor, nor contemplate that such right shall

deprive the State of a reasonable opportunity of fairly prosecuting

criminals. As held in Williams v. United States, for the

government to sustain its right to try the accused despite a delay, it

must show two things: (a) that the accused suffered no serious

prejudice beyond that which ensued from the ordinary and

inevitable delay; and (b) that there was no more delay than is

reasonably attributable to the ordinary processes of justice.

Closely related to the length of delay is the reason or

justification of the State for such delay. Different weights should

be assigned to different reasons or justifications invoked by the

State. For instance, a deliberate attempt to delay the trial in order to

hamper or prejudice the defense should be weighted heavily

against the State. Also, it is improper for the prosecutor to

intentionally delay to gain some tactical advantage over the

defendant or to harass or prejudice him. On the other hand, the

heavy case load of the prosecution or a missing witness should be

weighted less heavily against the State. x x x (emphasis supplied;

citations omitted)

Decision

12

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

As the right to a speedy disposition of cases encompasses the

broader purview of the entire proceedings of which trial proper is but a

stage, the above-discussed effects in Cm1Juz should equally apply to the

case at bar. 11 xx x (citations omitted; emphasis in the original)

Adopting respondents' position would defeat the very purpose of the

right against speedy disposition of cases. Upholding the same would allow a

scenario where the prosecution may deliberately exclude certain individuals

from the investigation only to file the necessary cases at another, more

convenient time, to the prejudice of the accused. Clearly, respondents'

assertion is subject to abuse and cannot be countenanced.

In the present case, petitioner has undoubtedly been prejudiced by

virtue of the delay in the resolution of the cases filed against him. Even

though he was not initially included as a respondent in the investigation

conducted from 1996 to 2006 pe1iaining to the "overpricing of medicines"

procured through emergency purchase, he has already been deprived of the

ability to adequately prepare his case considering that he may no longer have

any access to records or contact with any witness in support of his defense.

This is even aggravated by the fact that petitioner had been retired for fifteen

( 15) years. Even if he was never imprisoned and subjected to trial, it cannot

be denied that he has lived under a cloud of anxiety by virtue of the delay in

the resolution of his case.

WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The Resolutions

dated August 27, 2015 and October 28, 2015 of the Sandiganbayan First

Division in Criminal Case Nos. SB-11-CRM-0423, 0424, 0426, 0427, 0429,

0430, 0432, and 0433 are hereby ANNULLED and SET ASIDE.

The Sandiganbayan is likewise ordered to DISMISS Criminal Case

Nos. SB-1 l-CRM-0423, 0424, 0426, 0427, 0429, 0430, 0432, and 0433 for

violation of the constitutional right to speedy disposition of cases of

petitioner Commo. Lamberto R. Torres (Ret.).

SO ORDERED.

J. VELASCO, JR.

II

Id.

G.R. Nos. 221562-69

13

Decision

WE CONCUR:

EZ

Associate Justice

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the

Court's Division.

PRESBITER

J. VELASCO, JR.

CERTIFICATI

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the

Division Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the

above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was

assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Acting Chief Justice

You might also like

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- International Criminal Law Professor Scharf's Module on Nuremberg TrialsDocument245 pagesInternational Criminal Law Professor Scharf's Module on Nuremberg TrialsAlba P. Romero100% (1)

- In Re Speedy Disposition of CasesDocument63 pagesIn Re Speedy Disposition of CasesPatrick StarfishNo ratings yet

- 3-U PP vs. ParojinogDocument3 pages3-U PP vs. ParojinogShaine Aira ArellanoNo ratings yet

- III C Ledesma V CA GR No 161629 July 29 2005Document7 pagesIII C Ledesma V CA GR No 161629 July 29 2005Kristell FerrerNo ratings yet

- 7 - Aguinaldo v. Ventus'Document2 pages7 - Aguinaldo v. Ventus'AmberChan100% (1)

- DELAY IN REINVESTIGATION VIOLATED DUE PROCESSDocument2 pagesDELAY IN REINVESTIGATION VIOLATED DUE PROCESSJed Mendoza100% (1)

- Donation CasesDocument6 pagesDonation CasessalpanditaNo ratings yet

- Premids Obligations PDFDocument58 pagesPremids Obligations PDFayasueNo ratings yet

- Genuino V de Lima Case DigestDocument3 pagesGenuino V de Lima Case DigestAli100% (1)

- Supreme Court rules on right to speedy disposition of casesDocument2 pagesSupreme Court rules on right to speedy disposition of casesMaeBartolome100% (1)

- Supreme Court rules on search warrantDocument6 pagesSupreme Court rules on search warrantAlicia Jane NavarroNo ratings yet

- COMMO. LAMBERTO TORRES (RET) v. SANDIGANBAYANDocument1 pageCOMMO. LAMBERTO TORRES (RET) v. SANDIGANBAYANLara CacalNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Dismisses Case Due to Violation of Right to Speedy TrialDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Dismisses Case Due to Violation of Right to Speedy TrialLaurena ReblandoNo ratings yet

- 74th AmendmentDocument23 pages74th Amendmentadityaap100% (3)

- Palafox Vs Province of Ilocos NorteDocument3 pagesPalafox Vs Province of Ilocos NorteKrys Martinez0% (1)

- Compilation Cases 401 500 IncompleteDocument62 pagesCompilation Cases 401 500 IncompleteJuan Dela CruiseNo ratings yet

- 35 City of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityDocument2 pages35 City of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityClark LimNo ratings yet

- People vs Alfredo Rape Case Court RulingDocument2 pagesPeople vs Alfredo Rape Case Court RulingCarlaVercelesNo ratings yet

- Sandiganbayan Abused Discretion in Denying Motion to Dismiss Due to Inordinate DelayDocument5 pagesSandiganbayan Abused Discretion in Denying Motion to Dismiss Due to Inordinate DelayJoshua John Espiritu0% (1)

- Philippine Supreme Court Ruling Suspends Prosecutor for Neglecting CaseDocument5 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court Ruling Suspends Prosecutor for Neglecting CaseOlga Pleños ManingoNo ratings yet

- Salcedo v. Sandiganbayan (3rd Division) and People of The Philippines, G.R. Nos. 223869-960Document4 pagesSalcedo v. Sandiganbayan (3rd Division) and People of The Philippines, G.R. Nos. 223869-960Chinky Dane SeraspiNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Delay Violates Due ProcessDocument4 pagesOmbudsman Delay Violates Due ProcessjbjacildoNo ratings yet

- 9 - Raro V Sandiganbayan'Document2 pages9 - Raro V Sandiganbayan'AmberChanNo ratings yet

- Lopez V Ombudsman - DigestDocument2 pagesLopez V Ombudsman - Digestsmtm06100% (1)

- MOTION TO QUASH (Final)Document14 pagesMOTION TO QUASH (Final)jessasanchezNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Case DigestsDocument50 pagesBill of Rights Case DigestsClaire Elizabeth Abuan CacapitNo ratings yet

- Norman A. Johnson v. John Ashcroft, U.S. Attorney General Immigration and Naturalization Service, 378 F.3d 164, 2d Cir. (2004)Document11 pagesNorman A. Johnson v. John Ashcroft, U.S. Attorney General Immigration and Naturalization Service, 378 F.3d 164, 2d Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Zaldivar-Perez V First Division of The SandiganbayanDocument11 pagesZaldivar-Perez V First Division of The SandiganbayanLaurena ReblandoNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II - Article III - Section 16 To 20 - Case DigestsDocument3 pagesConstitutional Law II - Article III - Section 16 To 20 - Case DigestsBiyaya BellzNo ratings yet

- Labay V SandiganbayanDocument29 pagesLabay V SandiganbayanNeil reyesNo ratings yet

- Complainant vs. vs. Respondent: First DivisionDocument6 pagesComplainant vs. vs. Respondent: First DivisionJade ClementeNo ratings yet

- Crimpro 11-20Document9 pagesCrimpro 11-20karmela hernandezNo ratings yet

- 6 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanDocument9 pages6 Coscolluela V SandiganbayanFrances Angelica Domini KoNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V Llorente PDFDocument5 pagesPimentel V Llorente PDFDarren RuelanNo ratings yet

- Pleyto V PNP Crime InvestigationDocument44 pagesPleyto V PNP Crime InvestigationArianne BagosNo ratings yet

- Philippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceDocument90 pagesPhilippine Evidence Cases on Admissibility of Documents and Substantial ComplianceTerry FordNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument20 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SC Rules Petitioners' Right to Speedy Trial Violated in 8-Year Graft CaseDocument6 pagesSC Rules Petitioners' Right to Speedy Trial Violated in 8-Year Graft CaseMicah CandelarioNo ratings yet

- Villena Vs PeopleDocument4 pagesVillena Vs PeopleJohn Wick F. GeminiNo ratings yet

- 1-4 Rule 114 Part 1Document3 pages1-4 Rule 114 Part 1Eunice SerneoNo ratings yet

- Ilagan Vs Enrile - Full TextDocument5 pagesIlagan Vs Enrile - Full TextRomaine NuydaNo ratings yet

- Full Case Brief Crim 1Document111 pagesFull Case Brief Crim 1AngelNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit Rule - JurisprudenceDocument10 pagesJudicial Affidavit Rule - JurisprudenceJustin LoredoNo ratings yet

- Phillips v. Hines, 10th Cir. (2005)Document6 pagesPhillips v. Hines, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Uybuco vs. PeopleDocument5 pagesUybuco vs. PeopleMary Francel AblaoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- JUDGEMENT-Polyflor Limited vs. A.N. Goenka and OrsDocument13 pagesJUDGEMENT-Polyflor Limited vs. A.N. Goenka and OrsShirish ParasharNo ratings yet

- Filemon A. Verzano, JR., G.R. No. 171643 PresentDocument8 pagesFilemon A. Verzano, JR., G.R. No. 171643 PresentAnonymous ubixYANo ratings yet

- People v. Jikiri: Court Allows Prosecution to Amend Pre-Trial OrderDocument5 pagesPeople v. Jikiri: Court Allows Prosecution to Amend Pre-Trial OrderCris FloresNo ratings yet

- PRELIM - Media Law MC AdDUDocument136 pagesPRELIM - Media Law MC AdDUKimmy May Codilla-AmadNo ratings yet

- Gere vs. Anglo Eastern Jurisprudence On Labor LawDocument13 pagesGere vs. Anglo Eastern Jurisprudence On Labor LawAldos Medina Jr.No ratings yet

- SPO1 Lenito AcuzarDocument6 pagesSPO1 Lenito AcuzarJohn Vladimir A. BulagsayNo ratings yet

- C. George Swallow and Betty D. Swallow v. United States, 380 F.2d 710, 10th Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesC. George Swallow and Betty D. Swallow v. United States, 380 F.2d 710, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- DJJDDocument7 pagesDJJDCyril Mae VillavelezNo ratings yet

- Escobar v. People and Sandiganbayan, G.R. Nos. 228349 and 228353, September 19, 2018Document3 pagesEscobar v. People and Sandiganbayan, G.R. Nos. 228349 and 228353, September 19, 2018Chinky Dane SeraspiNo ratings yet

- Pimentel v. LlorenteDocument4 pagesPimentel v. LlorenteUnknown userNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 140679 January 14, 2004 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Appellee, vs. MANNY A. DOMINGCIL, AppellantDocument9 pagesG.R. No. 140679 January 14, 2004 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Appellee, vs. MANNY A. DOMINGCIL, AppellantKaren YuNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 166414, October 22, 2014: The RTC. However, The RTC Dismissed The Petition. The Petitioners Next Went To The CADocument6 pagesG.R. No. 166414, October 22, 2014: The RTC. However, The RTC Dismissed The Petition. The Petitioners Next Went To The CAGlaiza OtazaNo ratings yet

- Small Claims JurisprudenceDocument11 pagesSmall Claims JurisprudenceMay YellowNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V LlorenteDocument2 pagesPimentel V LlorenteRuab PlosNo ratings yet

- Lim V GamosaDocument2 pagesLim V GamosaJohnNo ratings yet

- 06 Rule120 - Villena vs. People, 641 SCRA 127, G.R. No. 184091 January 31, 2011Document11 pages06 Rule120 - Villena vs. People, 641 SCRA 127, G.R. No. 184091 January 31, 2011Galilee RomasantaNo ratings yet

- Coscolluela Vs Sandiganbayan G.R. 191411 July 15, 2013Document8 pagesCoscolluela Vs Sandiganbayan G.R. 191411 July 15, 2013MWinbee VisitacionNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument6 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Conditionel Contract To SellDocument2 pagesConditionel Contract To SellN.V.50% (2)

- 217194Document13 pages217194Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 223366Document25 pages223366Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Vera Vs AvelinoDocument42 pagesVera Vs AvelinoTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 226679Document21 pages226679Trishia Fernandez Garcia100% (3)

- Pelaez Vs AuditorDocument11 pagesPelaez Vs AuditorTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Direct Examination of The Expert WitnessDocument29 pagesDirect Examination of The Expert WitnessTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 224886Document15 pages224886Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 566 2011 2 PBDocument12 pages566 2011 2 PBTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 2011 235Document3 pages2011 235Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 210669Document23 pages210669Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 226679Document21 pages226679Trishia Fernandez Garcia100% (3)

- BoceaDocument25 pagesBoceaRam Migue SaintNo ratings yet

- Anak Vs ExecutiveDocument12 pagesAnak Vs ExecutiveTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Sema Vs ComelecDocument37 pagesSema Vs ComelecTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Anak Vs ExecutiveDocument12 pagesAnak Vs ExecutiveTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mmda Vs VironDocument26 pagesMmda Vs VironTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 566 2011 2 PBDocument12 pages566 2011 2 PBTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- KMUDocument12 pagesKMUTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Gerochi VsDocument21 pagesGerochi VsTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence June 2017 HighlightsDocument8 pagesJurisprudence June 2017 HighlightsTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Conference Vs PoeaDocument9 pagesConference Vs PoeaTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 213922Document14 pages213922Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 164171Document23 pagesG.R. No. 164171Kyle AlmeroNo ratings yet

- BoceaDocument25 pagesBoceaRam Migue SaintNo ratings yet

- 170341Document25 pages170341Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- November 2016 Philippine Court Decisions SummaryDocument3 pagesNovember 2016 Philippine Court Decisions SummaryTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Pimentel Ochia PDFDocument12 pagesPimentel Ochia PDFAms HussainNo ratings yet

- 219501Document13 pages219501Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- 227757Document11 pages227757Trishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Ortiz-Anglada v. Ortiz-Perez, 183 F.3d 65, 1st Cir. (1999)Document4 pagesOrtiz-Anglada v. Ortiz-Perez, 183 F.3d 65, 1st Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MENA Blasphemy Laws & ExtremismDocument3 pagesMENA Blasphemy Laws & ExtremismRose SabadoNo ratings yet

- M783 & Prem CF Ammo Rebate FORMDocument1 pageM783 & Prem CF Ammo Rebate FORMdunhamssports1No ratings yet

- Application To The Local Court: Notice of ListingDocument3 pagesApplication To The Local Court: Notice of ListingRoopeshaNo ratings yet

- In The Matter Of: Re U (Child) (1999)Document7 pagesIn The Matter Of: Re U (Child) (1999)Fuzzy_Wood_PersonNo ratings yet

- Compendium of Instructions Volume - 2 (English)Document355 pagesCompendium of Instructions Volume - 2 (English)remix1958No ratings yet

- Philippine Court Decision Appeal NoticeDocument2 pagesPhilippine Court Decision Appeal NoticeQueenie LeguinNo ratings yet

- Rule 1 - Part of Rule 3 Full TextDocument67 pagesRule 1 - Part of Rule 3 Full TextJf ManejaNo ratings yet

- PCW Barangay VAW Desk Handbook Tagalog December 2019Document112 pagesPCW Barangay VAW Desk Handbook Tagalog December 2019Genele PautinNo ratings yet

- Mambayya House: Aminu Kano Centre For Democratic StudiesDocument51 pagesMambayya House: Aminu Kano Centre For Democratic Studieshamza abdulNo ratings yet

- Reviewer 2Document122 pagesReviewer 2Lou AquinoNo ratings yet

- Law124 1stsem 12 13outlinerevisedDocument5 pagesLaw124 1stsem 12 13outlinerevisedClaudineNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines v. Sandiganbayan, Major General Josephus Q. Ramas and Elizabeth DimaanoDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines v. Sandiganbayan, Major General Josephus Q. Ramas and Elizabeth DimaanozacNo ratings yet

- Resolution On Standing Committee ChairmanshipDocument3 pagesResolution On Standing Committee ChairmanshipNikki BautistaNo ratings yet

- York County Court Schedule For March 24, 2016Document5 pagesYork County Court Schedule For March 24, 2016HafizRashidNo ratings yet

- Lgu-Zaragoza OpmaDocument11 pagesLgu-Zaragoza OpmaArrah BautistaNo ratings yet

- San Miguel Corporation v. MonasterioDocument6 pagesSan Miguel Corporation v. MonasterioAlyssaOgao-ogaoNo ratings yet

- History Class 9 FRENCH REVOLUTIONDocument18 pagesHistory Class 9 FRENCH REVOLUTIONAngadNo ratings yet

- Consitutional and Statutory Basis of TaxationDocument50 pagesConsitutional and Statutory Basis of TaxationSakshi AnandNo ratings yet

- Final ObliconDocument4 pagesFinal ObliconPortgas D. AceNo ratings yet

- Amritansh Agarwal: 15 Lacs 7 Yrs BhilaiDocument4 pagesAmritansh Agarwal: 15 Lacs 7 Yrs BhilaiAndreNo ratings yet

- Lahore High Court, Lahore: Judgment SheetDocument12 pagesLahore High Court, Lahore: Judgment SheetM Xubair Yousaf XaiNo ratings yet