Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Statin-Associated Weakness in Myasthenia Gravis: A Case Report

Uploaded by

tamionkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Statin-Associated Weakness in Myasthenia Gravis: A Case Report

Uploaded by

tamionkCopyright:

Available Formats

Keogh et al.

Journal of Medical Case Reports 2010, 4:61

http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/4/1/61

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL

CASE REPORTS

CASE REPORT

Open Access

Statin-associated weakness in myasthenia gravis:

a case report

Michael J Keogh*, John M Findlay, Simon Leach, John Bowen

Abstract

Introduction: Myasthenia gravis is a commonly undiagnosed condition in the elderly. Statin medications can

cause weakness and are linked to the development and deterioration of several autoimmune conditions, including

myasthenia gravis.

Case presentation: We report the case of a 60-year-old Caucasian man who presented with acute onset of

dysarthria and dysphagia initially attributed to a brain stem stroke. Oculobulbar and limb weakness progressed

until myasthenia gravis was diagnosed and treated, and until statin therapy was finally withdrawn.

Conclusion: Myasthenia gravis may be underappreciated as a cause of acute bulbar weakness among the elderly.

Statin therapy appeared to have contributed to the weakness in our patient who was diagnosed with myasthenia

gravis.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is characterised by fatigable

muscle weakness and has an incidence of only 1 in 5 to

10,000 people [1]. Autoimmune myasthenia gravis, often

in association with thymus hyperplasia or thymoma, can

affect young adults. However, it is now recognized that

myasthenia gravis is actually more prevalent in middleaged and older groups than younger age groups [2]. In

elderly patients, bulbar presentation is common [3] and

often mislabeled as a stroke [4] leading to poorer rates

of survival [5].

Statins (inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA

reductase) lower the incidence of cerebrovascular disease and coronary heart disease. Statin use has increased

dramatically over the last decade, with a four-fold

increase from 1996 to 1998 [6].

Although generally well-tolerated, statins may have

primary care discontinuation rates of up to 30% [7] due

to their side effects such as headache, myalgia, paraesthesia, and abdominal discomfort.

Here, we report a case of acute myasthenia gravis presenting in a 60-year-old Caucasian man whose condition

deteriorated until immunosuppressive therapy was commenced and statin therapy was withdrawn.

* Correspondence: mikekeogh@doctors.org.uk

Department of Stroke Medicine, United Lincolnshire Hospitals Trust, Lincoln

County Hospital, Lincoln, LN2 5QY, UK

Case presentation

A 60-year-old Caucasian man of British origin was

admitted to our hospital in September 2007 following

acute onset of dysarthria and dysphagia. He was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia three

months prior to presentation.

He had no visual disturbance or sensorimotor symptoms in his limbs or torso on presentation. He was commenced on gliclazide, ramipril and aspirin when he was

diagnosed with diabetes and hyperlipidemia 3 months

earlier. He was also started on simvastatin at that time,

but this was stopped following the development of proximal muscle weakness, myalgia, and an elevated creatine

kinase (CK) of 2599 (normal: <200), which all resolved

upon the termination of this medication. Gliclazide,

ramipril and aspirin, however, were continued.

Aside from the finding of mild dysarthria, examination

revealed that our patient had no remarkable conditions.

Results of routine haematology, biochemistry, thyroid

function tests, and creatine kinase were also unremarkable. His serum cholesterol was 6.1 mmol/L and his random blood glucose was 11.2 mmol/L.

An initial diagnosis of a brain stem stroke was considered, so dipyridamole and atorvastatin were added to his

medication four days after his admission to our hospital.

Meanwhile, a computed tomography (CT) brain scan

showed that he had no obvious infarct.

2010 Keogh et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keogh et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2010, 4:61

http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/4/1/61

Our patient remained stable over the next few days

with a mild dysarthria and dysphagia (tolerating soft

food), but no other symptoms or signs were noted.

One week after his admission to our hospital, his dysarthria and dysphagia worsened. Bilateral fatigable ptosis, diplopia, fatigable weakness of his neck flexion, and

shoulder abduction were noted for the first time. A previously planned cranial magnetic resonance brain scan

was thus cancelled.

Edrophonium testing demonstrated a dramatic transient improvement in his dysarthria, and a diagnosis of

myasthenia gravis with high titre anti-acetylcholine

receptor antibodies was confirmed. A serum immunoglobulin assay revealed an IgA level of <0.05 g/L. He

was noted to have normal IgG and IgM, and no paraprotein band.

Our patient was then commenced on treatment with

pyridostigmine. He was also started on incrementally

increasing prednisolone every other day. Regular monitoring of his respiratory function was also initiated.

His respiratory function worsened over the next 3

days. His spirometry also deteriorated. He developed a

new fatigable diplopia and an inability to stand from a

low squat position, together with increasing neck and

proximal limb weakness.

In view of his deteriorating state, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg) was commenced. Following

immunological advice regarding his low IgA titre, it was

decided to use Vigam Immunoglobulin (2 g/kg over the

next 4 days), which did not result in any adverse effect.

No objective gains were noted over the subsequent

week, and a repeat CK yielded a result of 842 mmol/L.

His atorvastatin medication was then stopped two weeks

after it had been introduced. Following this, our patient

showed significant improvement in ptosis, a resolution

of diplopia, and improved neck, shoulder, and elbow

power. His ability to stand from a low squat position

returned, and significant spirometric improvements

were also seen.

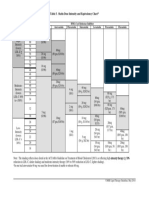

His CK readings fell over this period and returned to

normal levels one week after the cessation of his statin

medication (Figure 1).

Our patient remained stable until two weeks later

when, just prior to a planned discharge, a further deterioration and unresponsiveness to a second course of

IVIg necessitated respiratory and nutritional support,

intensive care, and plasma exchange.

Following prolonged treatment, his muscle strength

improved and he returned to independent living at

home four months after his admission to our hospital.

His gastrostomy feeding tube and tracheostomy were

removed 10 months after he was discharged from our

hospital.

Page 2 of 4

Discussion

Myasthenia gravis has an incidence of only 1 in every 5

to 10,000 people and is potentially fatal. A recent study

suggests that 2.2% of patients admitted with myasthenia

gravis overall died during admission [8], and that the

risk could be reduced by 69% if the patient is under the

care of a neurologist. It is thus important not to readily

dismiss the condition and that appropriate referrals are

made.

The actual incidence of statin-exacerbated myasthenia

is unknown, and only a handful of reports of statinassociated myasthenia gravis have ever been described

[9-11].

Out of 6 published case reports, only 5 patients were

noted to have some degree of recovery and only one

patient had a complete recovery upon termination of

statin therapy [11].

How statins could appear to exacerbate MG is

unclear. It is possible that the mechanism actually

reflects a double hit phenomenon of defective neuromuscular transmission secondary to antibody-mediated

post-synaptic acetylcholine receptor dysfunction in combination with a statin-induced myopathy.

The clear development of a statin myopathy with simvastatin treatment prior to the onset of myasthenia in

our patient is consistent with the possibility of a second

(atorvastatin- induced) myopathy coalescing with the

onset of myasthenia gravis. The symptomatic improvement that followed his withdrawal from atorvastatin

treatment resulted from the resolution of this statin

myopathy.

We also considered other potential causes of deterioration such as sepsis, steroid-induced worsening of

MG, steroid myopathy, and cholinergic crisis, but we

considered their development less likely based on clinical grounds.

We cannot rule out completely the possibility that the

worsening of our patients MG simply reflected a progression of his MG. However, the clinical course of his

condition, as well as the statin-induced proximal limb

pain and weakness (without bulbar features) he experienced prior to his presentation, raises at the very least

the possibility that a component of his initial deterioration was statin-related.

Similarly, we note that his improvement could have

reflected the immunosuppressive effects of therapy for

his MG rather than the withdrawal of his atorvastatin

treatment. It seems probable, however, that both factors

played a significant role in the improvement of his clinical state.

The development of other autoimmune disorders such

as dermatomyositis [12], polymyalgia rheumatica, vasculitis [13], and Lupus-like syndrome [14] upon initiation

Keogh et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2010, 4:61

http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/4/1/61

Page 3 of 4

Figure 1 This image of a graph shows creatinine kinase readings during admission, and a correlation to clinical progress.

of statin therapy [13] raises the possibility that in predisposed individuals, statins may precipitate an immunological trigger that is analogous to penicillamine-induced

MG [15] although clearly different in temporal respect.

However, given the paucity of reports and the widespread use of statins, the possibility of chance association cannot be excluded still.

Conclusion

Myasthenia gravis is a potentially fatal condition that

should be considered in elderly patients with bulbar

symptoms. Statin medication should be introduced cautiously and considered as a potential cause or precipitant of worsening muscle strength in patients with

myasthenia gravis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and any

accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is

available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this

journal.

Abbreviations

CK: creatinine kinase; CT: computed tomography; IVIg: intravenous

immunoglobulins; MG: myasthenia gravis.

Acknowledgements

None

Authors contributions

MJK reviewed the patients clinical data, performed the literature search, and

wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. JMF, SL and JB reviewed the initial

draft and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Received: 29 January 2008

Accepted: 20 February 2010 Published: 20 February 2010

References

1. Vincent A, Palace J, Hilton-Jones D: Myasthenia gravis. Lancet 2001,

357:2122-2128.

2. Slesak G, Melms A, Gerneth F, Sommer N, Weissert R, Dichgans J: Lateonset myasthenia gravis: follow-up of 113 patients diagnosed after age

60. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998, 841:777-780.

3. Vincent A, Clover L, Buckley V, Evans JG, Rothwell PM: Evidence of

underdiagnosis of myasthenia gravis in older People. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 2003, 74:1105-1108.

4. Kleiner-Fisman G, Kott HS: Myasthenia gravis mimicking stroke in elderly

patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1998, 73:1077-1078.

5. Christensen PB, Jensen TS, Tsiropoulos I, Sorensen T, Kjaer M, HojerPedersen E, Rasmussen M, Lehfeldt E: Mortality and survival in myasthenia

gravis: a Danish population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

1998, 64:78-83.

6. Packham C, Pearson J, Robinson J, Gray D: Use of statins in general

practices, 1996-1998: a cross sectional study. BMJ 2000, 320:1583-1584.

7. Simons LA, Simons J: Discontinuation rates of statins are high. BMJ 2000,

321:1084.

8. Hill M, Ben-Shlomo Y: Neurological care and risk of hospital mortality for

patients with myasthenia gravis in England. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

2008, 79(4):421-425.

9. Prvin A, Kawasaki A, Smith K, Kestler A: Statin-associated myasthenia

gravis: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore)

2006, 85:82-85.

Keogh et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2010, 4:61

http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/4/1/61

Page 4 of 4

10. Cartwright M, Jeffery D, Nuss G, Donofrio P: Statin-associated exacerbation

of myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2004, 63:2188.

11. Parmar B, Francis P, Ragge N: Statins, fibrates and ocular myasthenia.

Lancet 2002, 360:717.

12. Khattak FH, Morris IM, Branford WA: Simvastatin-associated

dermatomyositis. Br J Rheumatology 1994, 33:199.

13. Rudski L, Rabinovitch M, Danoff D: Systemic immune reactions to HMGCoA reductase inhibitors: a report of 4 cases and review of the

literature. Medicine 1998, 77:378-383.

14. Ahmad S: Lovastatin-induced lupus erthymatosus. Arch Int Med 1991,

151:1667-1668.

15. Wittbrodt E: Drugs and myasthenia gravis: an update. Arch Int Med 1997,

157:399-408.

doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-61

Cite this article as: Keogh et al.: Statin-associated weakness in

myasthenia gravis: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2010

4:61.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color figure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

You might also like

- Myasthenic Crisis with Myxedema and Dual Antibody PositivityDocument4 pagesMyasthenic Crisis with Myxedema and Dual Antibody PositivityFitria ChandraNo ratings yet

- tmpA8FD TMPDocument2 pagestmpA8FD TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Klair 2014Document3 pagesKlair 2014PabloIgLopezNo ratings yet

- A Pain in The Butt - A Case Series of Gluteal Compartment Syndrome - PMCDocument6 pagesA Pain in The Butt - A Case Series of Gluteal Compartment Syndrome - PMCchhabraanNo ratings yet

- Management of Morbid Obesity and Diabetes in Boy After Craniopharyngioma TreatmentDocument5 pagesManagement of Morbid Obesity and Diabetes in Boy After Craniopharyngioma Treatmentmuhammad_rosyidi_1No ratings yet

- Lithium Encephalopathy: D Smith P Keane J Donovan K Malone T J MckennaDocument2 pagesLithium Encephalopathy: D Smith P Keane J Donovan K Malone T J MckennaJosé Luis Gómez JuárezNo ratings yet

- Association of Myasthenia Gravis and Behçet's Disease: A CaseDocument4 pagesAssociation of Myasthenia Gravis and Behçet's Disease: A CaseTrần Văn ĐệNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis in The Elderly: NeurologyDocument4 pagesMyasthenia Gravis in The Elderly: NeurologyAirin QueNo ratings yet

- CCR3-5-1210Document3 pagesCCR3-5-1210NovelNo ratings yet

- Convulsive Seizures With A Therapeutic Dose of Isoniazid: Case ReportDocument4 pagesConvulsive Seizures With A Therapeutic Dose of Isoniazid: Case ReportSeptira MurtiningsihNo ratings yet

- JournalDocument3 pagesJournalJey GencianosNo ratings yet

- Journal of DiabetesDocument6 pagesJournal of DiabetesSartika Rizky HapsariNo ratings yet

- Two Takayasu Arteritis Patients Successfully Treated With Infliximab: A Potential Disease-Modifying Agent?Document8 pagesTwo Takayasu Arteritis Patients Successfully Treated With Infliximab: A Potential Disease-Modifying Agent?tera95No ratings yet

- ASIA Syndrome Following Breast Implant Placement: Case CommunicationsDocument3 pagesASIA Syndrome Following Breast Implant Placement: Case Communicationssilvana31No ratings yet

- Tratament of Miastenia GravisDocument9 pagesTratament of Miastenia GravisAndres MardonesNo ratings yet

- Paraneoplasic Encephalitis LalDocument13 pagesParaneoplasic Encephalitis Lalkmarmol77No ratings yet

- Article - Text 78439 3 10 20220829 PDFDocument19 pagesArticle - Text 78439 3 10 20220829 PDFAndré Iván SicairosNo ratings yet

- A. Discussion of The Health ConditionDocument5 pagesA. Discussion of The Health ConditionPeter AbellNo ratings yet

- Hiperglikemia & Geriatric - ICU-AWDocument9 pagesHiperglikemia & Geriatric - ICU-AWArmi ZakaNo ratings yet

- Hepatotoxicity Induced by High Dose of Methylprednisolone Therapy in A Patient With Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Brief Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesHepatotoxicity Induced by High Dose of Methylprednisolone Therapy in A Patient With Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Brief Review of LiteratureBayu ParmikaNo ratings yet

- N3102 Case Study: Musculoskeletal - Instructor Copy: Day 1 - Patient AssignmentDocument17 pagesN3102 Case Study: Musculoskeletal - Instructor Copy: Day 1 - Patient AssignmentBrittany LynnNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Hemichorea After Hyperglycemia CorrectionDocument3 pagesMedicine: Hemichorea After Hyperglycemia CorrectionanankastikNo ratings yet

- Pustaka 1Document7 pagesPustaka 1RizkyMaidisyaTaqwinNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Rhabdomyolysis Following Status Epilepticus With HyperuricemiaDocument3 pagesMedicine: Rhabdomyolysis Following Status Epilepticus With HyperuricemiaIsmi RachmanNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 021778Document11 pagesNejmoa 021778aandakuNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Ocular Myasthenia Gravis: Scott R. Haines, MD Matthew J. Thurtell, MBBSDocument10 pagesTreatment of Ocular Myasthenia Gravis: Scott R. Haines, MD Matthew J. Thurtell, MBBSTarun MathurNo ratings yet

- JFP 06309 Article1Document9 pagesJFP 06309 Article1Fcm-srAafNo ratings yet

- 10 Relato de Caso Acute CoronaryDocument4 pages10 Relato de Caso Acute CoronaryAsis FitrianaNo ratings yet

- Ep171984 CRDocument3 pagesEp171984 CRAssifa RidzkiNo ratings yet

- Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibodies in Patients With Optic and SeizuresDocument17 pagesAnti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibodies in Patients With Optic and SeizuresEmmanuel AguilarNo ratings yet

- JCO 2005 Pink 6809 11Document3 pagesJCO 2005 Pink 6809 11claudiaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus: Anaesthetic Management : ReviewarticleDocument4 pagesDiabetes Mellitus: Anaesthetic Management : Reviewarticledrdion mangku alamNo ratings yet

- Use of Anti-Epileptic Drugs in Post-Stroke Seizures:: A Cross-Sectional Survey Among British Stroke PhysiciansDocument3 pagesUse of Anti-Epileptic Drugs in Post-Stroke Seizures:: A Cross-Sectional Survey Among British Stroke Physiciansleo randa sebaztian simangunsongNo ratings yet

- HyperthyroidDocument7 pagesHyperthyroidHaerun Nisa SiregarNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutical Science Invention (IJPSI)Document3 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutical Science Invention (IJPSI)inventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Seizures and HypoglycemiaDocument2 pagesCase Study - Seizures and Hypoglycemiamob3No ratings yet

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis (2016-2017) Lecture NotesDocument9 pagesMyasthenia Gravis (2016-2017) Lecture NotesJibril AbdulMumin KamfalaNo ratings yet

- Immediate Recovery of Ischaemic Stroke Following Vitamin b1 AdministrationDocument2 pagesImmediate Recovery of Ischaemic Stroke Following Vitamin b1 AdministrationBill Jones Tanawal100% (1)

- Udy 2010Document3 pagesUdy 2010aNo ratings yet

- Examen DafdDocument5 pagesExamen DafdEdgar Villota OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation - Acute Kidney InjuryDocument5 pagesCase Presentation - Acute Kidney InjuryC KandasamyNo ratings yet

- Nursing VIVA FinalDocument9 pagesNursing VIVA FinalzakiatalhaNo ratings yet

- Unusual Presentation of Pancreatic Insulinoma:a Case ReportDocument5 pagesUnusual Presentation of Pancreatic Insulinoma:a Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- PBL 10Document4 pagesPBL 10lliioNo ratings yet

- Medical Complications After Stroke: A Multicenter StudyDocument8 pagesMedical Complications After Stroke: A Multicenter StudyVika AriliaNo ratings yet

- Acute Coronary Syndrome, STEMI, Anterior Wall, Killips - 1, DM Type II - UncontrolledDocument61 pagesAcute Coronary Syndrome, STEMI, Anterior Wall, Killips - 1, DM Type II - UncontrolledJai - Ho100% (5)

- Hypoglycemic Encephalopathy A Case Series and Literature Review On Outcome DeterminationDocument7 pagesHypoglycemic Encephalopathy A Case Series and Literature Review On Outcome Determinationc5qdk8jnNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Cushing. Maybe Not So Uncommon of An Endocrine DiseaseDocument10 pagesSíndrome de Cushing. Maybe Not So Uncommon of An Endocrine DiseaseStephany Gutiérrez VargasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anemia 1Document5 pagesJurnal Anemia 1reginsNo ratings yet

- MedulloblastomaDocument3 pagesMedulloblastomaMohammadAwitNo ratings yet

- Asymptomatic Aplastic Anemia Case Due to Anti-TB DrugsDocument4 pagesAsymptomatic Aplastic Anemia Case Due to Anti-TB DrugsayuNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Vertigo As A Predominant Manifestation of NeurosarcoidosisDocument5 pagesCase Report: Vertigo As A Predominant Manifestation of NeurosarcoidosisDjumadi AkbarNo ratings yet

- Seronegative Myasthenia Gravis Presenting With PneumoniaDocument4 pagesSeronegative Myasthenia Gravis Presenting With PneumoniaJ. Ruben HermannNo ratings yet

- Fulltext - Ams v5 Id1040Document4 pagesFulltext - Ams v5 Id1040yaneemayNo ratings yet

- Use of Human Embryonic Stem Cells in The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Case SeriesDocument6 pagesUse of Human Embryonic Stem Cells in The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Case SeriesAnonymous 7l69XWy12UNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument6 pages1 PBaulia fikriNo ratings yet

- Tugas Kelompok 3 - Penggunaan Obat Secara BijakDocument15 pagesTugas Kelompok 3 - Penggunaan Obat Secara BijakMaria IglesiaNo ratings yet

- Clozapine Induced Myocarditis: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesClozapine Induced Myocarditis: A Case ReportJAVED ATHER SIDDIQUINo ratings yet

- Clinical TrialDocument25 pagesClinical TrialHernawati Bagenda100% (1)

- DiabetologiDocument7 pagesDiabetologiSehati ChehaNo ratings yet

- Miliaria Definition, Types, Causes and TreatmentDocument31 pagesMiliaria Definition, Types, Causes and Treatmenttamionk0% (1)

- RosaceaDocument19 pagesRosaceatamionkNo ratings yet

- KonkliDocument2 pagesKonklitamionkNo ratings yet

- الخلاصه في 23 ورقهDocument23 pagesالخلاصه في 23 ورقهصلاح البازليNo ratings yet

- Statins Stimulate Atherosclerosis and Heart Failure Pharmacological MechanismsDocument12 pagesStatins Stimulate Atherosclerosis and Heart Failure Pharmacological MechanismsSonata DaniatiekNo ratings yet

- Thomas N. Tozer, Malcolm Rowland - Essentials of Pharmacokinetics and Pharma PDFDocument401 pagesThomas N. Tozer, Malcolm Rowland - Essentials of Pharmacokinetics and Pharma PDFSamNo ratings yet

- DIVERSE StudyDocument9 pagesDIVERSE StudyyashubyatappaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Case Analysis JohnDocument8 pagesModule 2 Case Analysis Johnkimwei clintonNo ratings yet

- Practice Test 2013 PDFDocument21 pagesPractice Test 2013 PDFDebarghya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Martini2012 PDFDocument10 pagesMartini2012 PDFSofia ImaculataNo ratings yet

- Final Research PaperDocument16 pagesFinal Research Paperapi-593862121No ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus National Clinical Management Guidelines Final Approved Version High Reso PDF July 6 2021Document107 pagesDiabetes Mellitus National Clinical Management Guidelines Final Approved Version High Reso PDF July 6 2021محمداحمد محمدنور ابايزيدNo ratings yet

- HYPERLIPIDEMIADocument16 pagesHYPERLIPIDEMIARoessalin PermataNo ratings yet

- RosuNext (Market Plan For PPI)Document15 pagesRosuNext (Market Plan For PPI)Muhammad UmerNo ratings yet

- Cardiology Pharmacology Review: HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors MechanismDocument74 pagesCardiology Pharmacology Review: HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors Mechanismshannon_marrero_1No ratings yet

- Group 5- PHARM 3D Case DiscussionDocument20 pagesGroup 5- PHARM 3D Case DiscussionCristine LalunaNo ratings yet

- Jama Style Lorem Ipsum EndnoteDocument2 pagesJama Style Lorem Ipsum Endnotegreeen.pat6918No ratings yet

- Effect of Malunggay (Moringa Oleifera) Capsules On Lipid and Glucose LevelsDocument6 pagesEffect of Malunggay (Moringa Oleifera) Capsules On Lipid and Glucose LevelsJulia DeleonNo ratings yet

- NEJM - Orion-10 and Orion-11 - 2020-03-18 ProtocolDocument598 pagesNEJM - Orion-10 and Orion-11 - 2020-03-18 ProtocolMets FanNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.251.182.254 On Sat, 18 Jan 2020 04:52:17 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.251.182.254 On Sat, 18 Jan 2020 04:52:17 UTCsinnanancyNo ratings yet

- Brian D. Smith - The Future of Pharma - Evolutionary Threats and Opportunities-Gower (2011)Document215 pagesBrian D. Smith - The Future of Pharma - Evolutionary Threats and Opportunities-Gower (2011)Marcelo Garbini100% (1)

- MCQ For FINAL (3&4)Document12 pagesMCQ For FINAL (3&4)api-2693862480% (5)

- 2021 Philippine Guidelines On PHEx Phase 1Document148 pages2021 Philippine Guidelines On PHEx Phase 1Famed residentsNo ratings yet

- Patient Decision Aid PDF 243780159 PDFDocument23 pagesPatient Decision Aid PDF 243780159 PDFJimboNo ratings yet

- Statin Dose Intensity and Equivalency ChartDocument1 pageStatin Dose Intensity and Equivalency ChartMavisVermilionNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Outcomes of PCSK9 InhibitorsDocument17 pagesCardiovascular Outcomes of PCSK9 InhibitorsAndi SusiloNo ratings yet

- Hyperlipidemia 1. PathophysiologyDocument2 pagesHyperlipidemia 1. PathophysiologyGlyneth FranciaNo ratings yet

- Statin Drugs-What Your Doctor Should Have Told YouDocument3 pagesStatin Drugs-What Your Doctor Should Have Told YouDr. Michael Ackerman100% (1)

- Dyslipidemia ATP4 GUIDLINESDocument9 pagesDyslipidemia ATP4 GUIDLINESSandy GunawanNo ratings yet

- List Signals Discussed Prac September 2012 - en Till 31-07-2023Document62 pagesList Signals Discussed Prac September 2012 - en Till 31-07-2023Amany HagageNo ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia: Hisham Aljadhey, Pharmd, PHDDocument55 pagesDyslipidemia: Hisham Aljadhey, Pharmd, PHDRany Waisya0% (1)

- CMS 2013 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) Claims/Registry Measure Specifications ManualDocument637 pagesCMS 2013 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) Claims/Registry Measure Specifications ManualHLMeditNo ratings yet