Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inmate Lawsuit

Uploaded by

Daily Freeman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

77 views5 pagesPATRICK J. WASSMANN JR. v. COUNTY OF ULSTER, et al.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPATRICK J. WASSMANN JR. v. COUNTY OF ULSTER, et al.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

77 views5 pagesInmate Lawsuit

Uploaded by

Daily FreemanPATRICK J. WASSMANN JR. v. COUNTY OF ULSTER, et al.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

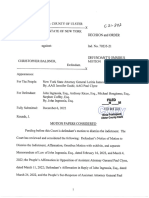

State of New York

Supreme Court, Appellate Division

Third Judicial Department

Decided and Entered: November 23, 2016

________________________________

PATRICK J. WASSMANN JR.,

Appellant,

v

522709

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

COUNTY OF ULSTER et al.,

Respondents.

________________________________

Calendar Date:

Before:

October 14, 2016

McCarthy, J.P., Garry, Lynch, Devine and Clark, JJ.

__________

Bloom & Bloom, PC, New Windsor (Robert N. Isseks,

Middletown, of counsel), for appellant.

Cook, Netter, Cloonan, Kurtz & Murphy, PC, Kingston (Robert

D. Cook of counsel), for respondents.

__________

Devine, J.

Appeal from an order of the Supreme Court (Work, J.),

entered June 22, 2015 in Ulster County, which, among other

things, granted defendants' motion for summary judgment

dismissing the complaint.

On July 13, 2010, while an inmate at the Ulster County

Jail, plaintiff was assaulted by another inmate and sustained

injuries. Plaintiff thereafter commenced this negligence action

against defendants.1 Defendants moved for summary judgment

Plaintiff previously commenced a federal action against

defendants, asserting a cause of action under 42 USC 1983, that

was dismissed due to the absence of proof that defendants "acted

-2-

522709

dismissing the complaint following joinder of issue and

discovery, while plaintiff cross-moved for a variety of relief

that included summary judgment on the issue of liability.

Supreme Court granted defendants' motion, dismissed the complaint

and denied the remainder of the relief sought by plaintiff as

moot. Plaintiff now appeals, focusing upon the grant of summary

judgment to defendants.

"Having assumed physical custody of inmates, who cannot

protect and defend themselves in the same way as those at liberty

can, the [s]tate [or its political subdivisions] owe[] a duty of

care to safeguard inmates, even from attacks by fellow inmates"

(Sanchez v State of New York, 99 NY2d 247, 252 [2002] [citations

omitted]; see Smith v County of Albany, 12 AD3d 912, 913 [2004]).

This duty of care does not render the custodial entity "an

insurer of inmate safety[,] and negligence cannot be inferred

merely because an incident occurred" (Vasquez v State of New

York, 68 AD3d 1275, 1276 [2009]; Sanchez v State of New York, 99

NY2d at 253). The duty owed is instead "limited to providing

reasonable care to protect inmates from risks of harm that are

reasonably foreseeable, i.e., those that [the custodial entity or

its agents] knew or should have known" (Vasquez v State of New

York, 68 AD3d at 1276; see Sanchez v State of New York, 99 NY2d

at 253; Smith v County of Albany, 12 AD3d at 913).

Plaintiff alleges, as is relevant here, that defendants

were negligent by not taking into account the assailant's violent

conduct while previously imprisoned and placing him in "close

custody" at the jail. Defendants did not have actual knowledge

that the assailant, who had no disciplinary issues in the leadup

with the deliberate indifference to inmate safety necessary for

an Eighth Amendment claim" (Wassmann v County of Ulster, N.Y.,

528 Fed Appx 105, 107 [2d Cir 2013]). Defendants make much of

that dismissal on appeal, but it suffices to say that "deliberate

indifference . . . requires more than [the] showing of mere

negligence" demanded of plaintiff here (Rodriguez v City of New

York, 87 AD3d 867, 869 [2011] [internal quotation marks and

citations omitted]; see Farmer v Brennan, 511 US 825, 835

[1994]).

-3-

522709

to the assault, had violent propensities. Defendants further

demonstrated that the information in their possession gave them

no reason to believe that the assailant had a specific problem

with plaintiff. Plaintiff responds by pointing out that

defendants failed to obtain records related to the assailant's

prior time in state prison and that, had they done so, they would

have learned that the assailant had engaged in violent conduct

while imprisoned in 2003 and 2005.

Plaintiff first argues that a statutory duty existed to

obtain those records, and a "violation of a [s]tate statute that

imposes a specific duty constitutes negligence per se" (Elliott v

City of New York, 95 NY2d 730, 734 [2001]; see Yenem Corp. v 281

Broadway Holdings, 18 NY3d 481, 489 [2012]; Bauer v Female

Academy of Sacred Heart, 97 NY2d 445, 453 [2002]). Correction

Law 500-b (7) (a) states that the reviewing officer "shall

exercise good judgment and discretion and shall take all

reasonable steps to ensure that the assignment of persons to

facility housing units" advances the safety and security of all

inmates and that of the facility in general. The statute

enumerates a number of factors to consider in that analysis, but

an inmate's history of assaultive behavior or his or her prior

prison disciplinary history are not among them (see Correction

Law 500-b [7] [b]; cf. Arnold v County of Nassau, 89 F Supp 2d

285, 299-300 [ED NY 2000], vacated on different grounds 252 F3d

599 [2d Cir 2001] [negligence per se where the custodian

disregarded specific criteria set forth in Correction Law 500-b

(7)]). The statute further lacks a specific requirement that the

reviewing officer obtain all records pertaining to an inmate,

instead directing a review of whatever "relevant and known"

records are "accessible and available" (Correction Law 500-b

[7] [c] [3]). The statute accordingly creates a "possibility of

exceptions . . . significant enough to justify a case-by-case

determination of negligence without the automatic imposition of

negligence under the negligence per se doctrine," although a

failure to obtain specific records could well constitute evidence

of negligence in a given case (Dance v Town of Southampton, 95

AD2d 442, 447 [1983]; see Schmidt v Merchants Despatch Transp.

Co., 270 NY 287, 305 [1936]).

Turning to whether questions of fact exist as to

-4-

522709

plaintiff's common-law negligence claim, the regulations

implementing Correction Law 500-b direct that the reviewing

official consider an inmate's "attitude and behavior during

present and prior incarceration(s)" in making a housing

assignment, necessitating a review of disciplinary records from

prior stays in prison (9 NYCRR 7013.8 [c] [8] [emphasis added]).

The reviewing official here, defendant Michael Coughlin, did not

consider the assailant's prior prison disciplinary records, and

that omission constituted a violation of the regulation that is

"some evidence of negligence" (Bauer v Female Academy of Sacred

Heart, 97 NY2d at 453). Coughlin completed a classification

worksheet reflecting that, even without factoring in the

assailant's conduct while previously confined, the assailant

should be placed in close custody due to his violent criminal

history and the existence of a detainer warrant against him.

Inasmuch as the assailant had "never been in [the jail] and [was

not] a discipline problem," however, Coughlin disregarded the

classification suggested by those "policies and practices

designed to address" risks to the safety of others and placed the

assailant in general population (Sanchez v State of New York, 99

NY2d at 254; see Brown v City of New York, 95 AD3d 1051, 1052

[2012]). Coughlin averred that he still would have allowed the

assailant to enter general population had he known of the

assailant's prior disciplinary history, as the incidents of

violence occurred several years before the events at issue here.

Nevertheless, the foregoing raises questions of fact as to

whether defendants may have failed to take action to address a

reasonably foreseeable threat that resulted in the assault upon

plaintiff, and those questions must be resolved at trial (see

Smith v County of Albany, 12 AD3d at 913-914).

McCarthy, J.P., Garry, Lynch and Clark, JJ., concur.

-5-

522709

ORDERED that the order is modified, on the law, without

costs, by reversing so much thereof as granted defendants' motion

for summary judgment dismissing the complaint; motion denied;

and, as so modified, affirmed.

ENTER:

Robert D. Mayberger

Clerk of the Court

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Public Service Investigation Report On Central HudsonDocument62 pagesPublic Service Investigation Report On Central HudsonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Real Property Tax Audit With Management Comment and ExhibitsDocument29 pagesReal Property Tax Audit With Management Comment and ExhibitsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger Order Regarding Implementation of The New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection ActDocument4 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger Order Regarding Implementation of The New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection ActDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms Notarial WillDocument4 pagesLegal Forms Notarial WillClaire Margot CastilloNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- New York State Senate Committee Report On Utility Pricing PracticesDocument119 pagesNew York State Senate Committee Report On Utility Pricing PracticesDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger's Open LetterDocument2 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger's Open LetterDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- BARECON 2017 v2Document22 pagesBARECON 2017 v2rafaelNo ratings yet

- Jane Doe v. Bard CollegeDocument55 pagesJane Doe v. Bard CollegeDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- FI To MM IntegrationDocument8 pagesFI To MM IntegrationsurendraNo ratings yet

- Business Law - Pledge, Mortgage and AntichresisDocument11 pagesBusiness Law - Pledge, Mortgage and AntichresisrickyNo ratings yet

- Central Hudson Class Action LawsuitDocument30 pagesCentral Hudson Class Action LawsuitDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- NY AG Report On Saugerties Police Officer Dion JohnsonDocument15 pagesNY AG Report On Saugerties Police Officer Dion JohnsonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Three Stages of DiversionDocument2 pagesThree Stages of DiversionLea BanasigNo ratings yet

- RCBC Vs ArroDocument2 pagesRCBC Vs ArroakimoNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Filed by Charles Whittaker Against Donald Markle and Joseph MaloneyDocument9 pagesLawsuit Filed by Charles Whittaker Against Donald Markle and Joseph MaloneyDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Joseph Maloney's Affidavit in SupportDocument12 pagesJoseph Maloney's Affidavit in SupportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Fire Investigators Report On Oct. 10, 2023, Fire in KerhonksonDocument19 pagesFire Investigators Report On Oct. 10, 2023, Fire in KerhonksonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Kingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDocument9 pagesKingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Out of Reach 2023Document17 pagesOut of Reach 2023Daily Freeman100% (1)

- Ulster County First Quarter 2023 Financial ReportDocument7 pagesUlster County First Quarter 2023 Financial ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Vassar College Class Action ComplaintDocument25 pagesVassar College Class Action ComplaintDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Solar PILOTs Audit - Review of Billing and CollectionsDocument7 pagesUlster County Solar PILOTs Audit - Review of Billing and CollectionsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Tyrone Wilson StatementDocument2 pagesTyrone Wilson StatementDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Filed by Frank and Pam Eighmey Against Town of WoodstockDocument46 pagesLawsuit Filed by Frank and Pam Eighmey Against Town of WoodstockDwayne Kroohs100% (1)

- Ulster County Sales Tax Revenues 2022Document2 pagesUlster County Sales Tax Revenues 2022Daily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger Open Letter On County FinancesDocument2 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger Open Letter On County FinancesDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- HydroQuest UCRRA Landfill Siting Report 1-05-22 With MapsDocument29 pagesHydroQuest UCRRA Landfill Siting Report 1-05-22 With MapsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger, Municipal Leaders Letter Over Rail SafetyDocument3 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger, Municipal Leaders Letter Over Rail SafetyDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Terramor Application Withdrawa February 2023Document1 pageTerramor Application Withdrawa February 2023Daily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan ResponseDocument3 pagesUlster County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan ResponseDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Schumer RRs Safety LetterDocument2 pagesSchumer RRs Safety LetterDaily Freeman100% (1)

- Central Hudson Response To Public Service Commission ReportDocument92 pagesCentral Hudson Response To Public Service Commission ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- 2022 Third Quarter Financial ReportDocument7 pages2022 Third Quarter Financial ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Letter To Ulster County Executive Regarding Request For Updated Emergency PlanDocument1 pageLetter To Ulster County Executive Regarding Request For Updated Emergency PlanDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Judge Ruling Dismisses Murder Charge Against State TrooperDocument23 pagesUlster County Judge Ruling Dismisses Murder Charge Against State TrooperDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Democrats' Lawsuit Seeking New Ulster County Legislative MapsDocument21 pagesDemocrats' Lawsuit Seeking New Ulster County Legislative MapsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Eldomiaty Et. Al (2020)Document12 pagesEldomiaty Et. Al (2020)Leonardo VelizNo ratings yet

- Posner JurisprudenceGreed 2003Document38 pagesPosner JurisprudenceGreed 20038dmz7sbtvcNo ratings yet

- Filipino ResearchDocument2 pagesFilipino ResearchKielene PalosNo ratings yet

- Organizational Development ThesisDocument4 pagesOrganizational Development Thesisbk184deh100% (2)

- Related Philippine Standards in Auditing (Psas) : November 16, 2020Document30 pagesRelated Philippine Standards in Auditing (Psas) : November 16, 2020Aki StephyNo ratings yet

- Compound Interest Calculator - Daily, Monthly, Yearly CompoundingDocument1 pageCompound Interest Calculator - Daily, Monthly, Yearly CompoundingEhsanNo ratings yet

- Law Dictionary: by Susan Ellis Wild, Legal EditorDocument332 pagesLaw Dictionary: by Susan Ellis Wild, Legal EditorFlan Chris Junior DiomandeNo ratings yet

- Global Migration ReferenceDocument28 pagesGlobal Migration ReferenceBabee HaneNo ratings yet

- 74 - INTEC Cebu v. CA, June 22, 2016Document2 pages74 - INTEC Cebu v. CA, June 22, 2016Christine ValidoNo ratings yet

- International Research Assistant or Administrative Assistant ChecklistDocument1 pageInternational Research Assistant or Administrative Assistant ChecklistJubaeR Inspire TheFutureNo ratings yet

- Loans Appraisal GuidelinesDocument15 pagesLoans Appraisal GuidelinesMichael KattaNo ratings yet

- "Yes, But Not To The Fullest in My Opinion." - Threjann Ace NoliDocument2 pages"Yes, But Not To The Fullest in My Opinion." - Threjann Ace NoliJANNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle: Chapter 1-Chapter 4 1Document18 pagesAccounting Cycle: Chapter 1-Chapter 4 1CHRISHA PARAGASNo ratings yet

- General Knowledge - Awareness Quiz - Multiple Choice Question (MCQ) Answers Solution 2013 Online Mock TestDocument8 pagesGeneral Knowledge - Awareness Quiz - Multiple Choice Question (MCQ) Answers Solution 2013 Online Mock TestSanjay Thapa100% (1)

- Study Guide For Module No.Document5 pagesStudy Guide For Module No.Darlene Dacanay DavidNo ratings yet

- Living With Art 11th Edition Mark Getlein Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesLiving With Art 11th Edition Mark Getlein Solutions Manualbombyciddispelidok100% (18)

- Graph of Vertical and Horizontal Measurements Over TimeDocument2 pagesGraph of Vertical and Horizontal Measurements Over TimeWan Wan SetyawanNo ratings yet

- (Los Angeles) Cyber Crisis Management Planning Professional Boot Camp Tickets, Tue 21 Jan 2020 at 9 - 00 AM - Eventbrite PDFDocument8 pages(Los Angeles) Cyber Crisis Management Planning Professional Boot Camp Tickets, Tue 21 Jan 2020 at 9 - 00 AM - Eventbrite PDFtuskar godlike3No ratings yet

- Documents Requisition Form Blank FINALDocument1 pageDocuments Requisition Form Blank FINALdidid2No ratings yet

- American History Module One Lesson Four ActivityDocument3 pagesAmerican History Module One Lesson Four Activitymossohf293No ratings yet

- Name List Form 5 2023Document10 pagesName List Form 5 2023Muhamad IpeayNo ratings yet

- MB No Go Zone For Reprisal or Local Preference Clauses in Public Tenders FriesenDocument1 pageMB No Go Zone For Reprisal or Local Preference Clauses in Public Tenders FriesenJohn WestNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Quiz MaterialDocument4 pagesLesson 2 Quiz Materiallinkin soyNo ratings yet

- CONWORLD - Global City, Demography, MigrationDocument7 pagesCONWORLD - Global City, Demography, Migrationbea marieNo ratings yet