Professional Documents

Culture Documents

No Charges Approved in Paige Gauchier Case

Uploaded by

CKNW980Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

No Charges Approved in Paige Gauchier Case

Uploaded by

CKNW980Copyright:

Available Formats

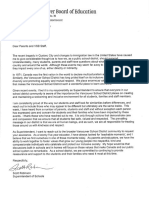

MEDIA STATEMENT

CRIMINAL JUSTICE BRANCH

December 6, 2016

16-27

No Charges Approved in RCMP Investigation re: Paige Gauchier

Victoria - The Criminal Justice Branch, Ministry of Justice (CJB) announced today that

no charges have been approved against the Delta Police Service officers and

paramedics who dealt with Paige Gauchier on January 22, 2011 and did not report the

incident to the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD).

The incident was investigated by the RCMP which subsequently submitted a Report to

Crown Counsel to CJB recommending charges of failing to report a child in need of

protection contrary to section 14(1) of the Child, Family and Community Services Act.

CJB has concluded, based on the available evidence, that there is no substantial

likelihood that the officers or paramedics would be convicted of the offence

recommended by the RCMP. The decision, which is explained in greater detail in the

attached Clear Statement, follows an extensive and thorough review of the available

evidence by Crown Counsel.

In order to maintain confidence in the integrity of the criminal justice system, a Clear

Statement explaining the reasons for not approving charges is made public by CJB in

high profile cases where the investigation has become publicly known.

Media Contact:

Dan McLaughlin

Communications Counsel

Criminal Justice Branch

(250) 387-5169

To learn more about B.C.'s criminal justice system visit the British Columbia Prosecution

Service website at: www.gov.bc.ca/prosecutionservice

Branch Vision

Courageous, Fair and Efficient A Prosecution Service that has the Confidence of the Public..

Office of the

Assistant Deputy Attorney General

Criminal Justice Branch

Ministry of Justice and Attorney General

Mailing Address:

PO Box 9276 Stn Prov Govt

Victoria, BC V8W 9J7

Office Location:

th

9 Floor, 1001 Douglas Street

Victoria, BC V8W 9J7

Telephone: (250) 387-3840

Fax: (250) 387-0090

- 2 -

Clear Statement

16-27

Summary of Decision

Just after 2:00 AM on January 22, 2011, 17 year-old Paige Gauchier walked into a gas

station in Delta. She was intoxicated and suffering from a sore, slightly bleeding nose.

She said that she had recently been assaulted by six girls but she was unclear on the

details.

The Delta Police and the British Columbia Ambulance Service (BCAS) attended.

Paramedics determined that Ms. Gauchiers injuries were minor but they recommended

that she go to hospital. She refused. The police then spoke to her uncle in Vancouver,

who asked that she be delivered by taxi to his residence. The police understood that he

was her guardian and that she was living with him at the time. Neither the police nor the

BCAS paramedics reported the incident to the Ministry of Child and Family

Development (MCFD).

Just over two years later, in April 2013, Ms. Gauchier was found dead in a public

washroom adjacent to Oppenheimer Park in Vancouver. The cause of death was a drug

overdose. She was 19. The Representative for Children and Youth (RCY) subsequently

conducted an extensive investigation of Ms. Gauchiers life, and released her findings in

May 2015 as Paiges Story.

A major focus of the RCYs report was a review of numerous contacts Ms. Gauchier had

during her life with police, paramedics, health care workers, school staff, and others

who typically come into contact with children in distress. In the RCYs opinion, many of

those contacts should have been reported to the MCFD, pursuant to the Child, Family

and Community Service Act (the Act) because Ms. Gauchier was a reportable child in

need of protection as defined in the Act.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, in his role as president of the Union of British Columbia

Indian Chiefs, requested that police investigate to determine if any offences of failing to

report a child in need of protection had been committed. Ms. Gauchier was of

Indigenous ancestry.

The RCMP completed an investigation and submitted a Report to Crown Counsel in

March 2016 recommending that the main police investigator and two paramedics who

dealt with Ms. Gauchier on January 22, 2011, be charged with failing to report a child in

need of protection to the MCFD, contrary to section 14(1) of the Act.

Charge Assessment and the Criminal Standard of Proof

The Charge Assessment Guidelines applied by the Criminal Justice Branch in reviewing

all Reports to Crown Counsel are established in Branch policy and are available online

at:

www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal-justice/prosecution-service/crowncounsel-policy-manual/cha-1-charge-assessment-guidelines.pdf

- 3 -

Under the Charge Assessment Guidelines, charges will only be approved where Crown

Counsel is satisfied that the evidence gathered by the investigative agency provides a

substantial likelihood of conviction and, if so, that a prosecution is required in the public

interest. The charge assessment in this case was conducted by senior Crown Counsel

with knowledge of the applicable legislation, the relevant case law, and the legal and

evidentiary issues that can arise in this kind of case. Crown Counsel conducting the

charge assessment reviewed the material provided by the RCMP and had ongoing

communications with the RCMP during the charge assessment process to ensure that

Crown Counsel had a solid understanding of the available evidence.

In making a charge assessment, Crown Counsel must review the evidence gathered by

investigators in light of the legal elements of any offence that may have been

committed. Crown Counsel must also remain aware of the presumption of innocence,

the prosecutions burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt and the fact that under

Canadian criminal law, a reasonable doubt can arise from the evidence, the absence of

evidence, inconsistencies in the evidence or the credibility or reliability of one or more of

the witnesses. The person accused of a crime does not have to prove that he or she did

not commit the crime. Rather, the Crown bears the burden of proof from beginning to

end. When assessing the strength of the case the Crown must also consider the

likelihood that viable defences will succeed.

Potential Charges

The potential charge that was considered in this assessment was under section 14(1) of

the Act, which provides that:

A person who has reason to believe that a child needs protection under section

13 must promptly report the matter to a director or a person designated by a

director.

Relevant Law

The Duty to Report

There have been no prosecutions for breaching the duty to report in British Columbia.

There have been some reported cases for a similar offence in Ontario, where the duty

to report has been narrowly interpreted. The outcome in all of the reported cases from

outside BC ultimately turned on issues that do not arise in the present case.

Child in Need of Protection

Section 13(1) of the Act identifies a broad array of circumstances in which a child is

defined as a child in need of protection, including if the child is absent from home in

circumstances that endanger the childs safety or well-being. If a director is informed

that a child is in need of protection, the director has wide powers under the Act to

investigate, to provide assistance and support, or even to remove a child whose health

or safety is in immediate danger.

- 4 -

Section 13 has been judicially considered and has been given an expansive

interpretation in order to ensure that children are protected from abuse, neglect, harm,

or the threat of harm. The circumstances listed in s. 13 are not exclusive or exhaustive.

Courts have noted that while children must be protected from harm, child welfare

legislation does not mandate protection from every conceivable harm. The harm must

be significant, and not trifling or transitory in nature. It must be substantial enough to

warrant direct intervention by government, beyond mere government assistance

through the provision of support services. Courts have also noted the risks associated

with raising children and that it is not uncommon for children to stray beyond safe

boundaries. Not all such cases are indicative of a lack of supervision that would require

the Director to take child protection steps.1

Judicial commentary and the context of the Act indicate that the basis for governmental

intervention, and therefore the duty to report, requires both harm (or the threat of harm)

to the child and an unsatisfactory home situation, and a connection between the two.

In summary, the case law provides three helpful parameters for the definition of child in

need of protection and therefore the scope of the duty to report:

a. Harm means harm that is more than trifling or transitory in nature;

b. There must be a need for governmental intervention rather than simply

governmental assistance; and,

c. The duty to report must be considered in the context of the childs home

situation since the Act is essentially aimed at ameliorating unsatisfactory

home situations. In other words, the duty to report requires a nexus between

harm (or the threat of harm) to a child and an unsatisfactory home situation.

The Circumstances Surrounding the Incident

On the date of the incident, Ms. Gauchier was 17 years old. She was alone, and had

walked into a gas station just after 2:00 AM, impaired by alcohol and suffering a sore,

slightly bleeding nose. A paramedic recorded the injury as a soft tissue injury. Ms.

Gauchier said she had been in Surrey, and had been picked up, driven somewhere

unknown, and then assaulted by six females. Delta Police reported the assault

allegation to the Surrey RCMP. Ms. Gauchier refused to go to hospital as urged by the

paramedics.

Ms. Gauchier was not in the care of MCFD at the time. Police learned that she was

living with her uncle whom they understood to be her guardian. At the uncles request,

the police put Ms. Gauchier in a taxi to go to his home in Vancouver.

Neither the police nor the paramedics reported the incident to MCFD.

The first responders had no information suggesting that Ms. Gauchier was being

abused or neglected by a parent or guardian. They indicated to the RCMP members

investigating the alleged failure to report that they did not consider the incident

1

J.L. (Re), 2011 YKTC 61, paras 39 - 42.

- 5 -

reportable as there were no indications of a problem in Ms. Gauchiers home. One of

the first responders noted that he saw no reason to report the matter of a 17 year-old

who had been drinking alcohol, as that was something he came across on a regular

basis, probably ten times a day.

Application of the Law to the Circumstances of the Case

Crown Counsel determined that there was a narrower and a broader possible

interpretation that could be given to the offence of failing to report under the Act, giving

rise to two possible routes to culpability:

1. The duty to report might be said to arise if Ms. Gauchier were suffering abuse or

neglect at the hands of a parent or guardian; or,

2. The duty to report might be said to arise if Ms. Gauchier were at risk of non-trivial

harm or the threat of non-trivial harm, and there were some nexus between the

harm or threat of harm and Ms. Gauchiers home situation.

On either interpretation, Crown Counsel determined that the available evidence would

not support a finding of a failure to report under s. 14(1) of the Act.

There is no evidence to suggest that the paramedics and police who dealt with Ms.

Gauchier on January 22, 2011, had any reason to believe Ms. Gauchiers uncle or

anyone else in his household had supplied her with liquor or had injured her in Surrey or

Delta. Further, they had no reason to believe she was neglected by her uncle or that

such neglect played any part in Ms. Gauchiers circumstances on January 22, 2011.

It is a reality of contemporary life that parents and guardians have limited ability to

monitor and control the behaviour of children in their late teens. It is not unusual for

teenagers to be out late at night unsupervised and to be drinking. It is also not unusual

for teenagers to become involved in physical altercations with their peers. Neither of

these situations necessarily suggests neglect on the part of parents or guardians.

The paramedics attended to Ms. Gauchiers apparent injuries and suggested that she

go to the hospital. She refused. The police ensured Ms. Gauchier was delivered by taxi

to her uncles home, which they believed to be her residence, and which appeared to be

a suitable and safe place for her to go. In fact, in her Report the RCY commented that

living with her uncle was one of the best options for Ms. Gauchier.2

In the circumstances, it would have been reasonable for the paramedics and police to

conclude Ms. Gauchier was not a child in need of protection and that a report to a

director was neither appropriate nor necessary.

Conclusion

There is no substantial likelihood of conviction under s.14(1) of the Act, and as such, no

charges have been approved.

2

Paiges Story at p 7.

You might also like

- Missing Pieces: Joshua's StoryDocument66 pagesMissing Pieces: Joshua's StoryAshley WadhwaniNo ratings yet

- Judge Silverman Re Basyal v. Macs Convenience Stores Inc. 09-18Document43 pagesJudge Silverman Re Basyal v. Macs Convenience Stores Inc. 09-18CKNW980No ratings yet

- Minister Bruce Ralston Retraction - August 12, 2017Document1 pageMinister Bruce Ralston Retraction - August 12, 2017CKNW980No ratings yet

- Statement From Deputy Minister Kim HendersonDocument2 pagesStatement From Deputy Minister Kim HendersonCKNW980No ratings yet

- NDP-Green AgreementDocument10 pagesNDP-Green AgreementThe Globe and Mail100% (1)

- Abbotsford School District Report Into Deadly Stabbing Last FallDocument31 pagesAbbotsford School District Report Into Deadly Stabbing Last FallCKNW980No ratings yet

- 06/20/17 - Angus Reid Institute Poll: Snap Elections?Document21 pages06/20/17 - Angus Reid Institute Poll: Snap Elections?The Vancouver SunNo ratings yet

- Ipsos Reid - TablesDocument4 pagesIpsos Reid - TablesCKNW980No ratings yet

- CCSA Life in Recovery From Addiction Report 2017Document84 pagesCCSA Life in Recovery From Addiction Report 2017Ashley WadhwaniNo ratings yet

- BC Political Release PDFDocument4 pagesBC Political Release PDFCKNW980No ratings yet

- BC Political Release PDFDocument4 pagesBC Political Release PDFCKNW980No ratings yet

- John Horgan Letter To BC HydroDocument2 pagesJohn Horgan Letter To BC HydroThe Vancouver SunNo ratings yet

- Grizzly FoundationDocument90 pagesGrizzly FoundationCKNW980No ratings yet

- Mainstreet - B.C. April 29-May 1Document11 pagesMainstreet - B.C. April 29-May 1Mainstreet100% (1)

- REBGV Statistics For May 2017Document9 pagesREBGV Statistics For May 2017CKNW980No ratings yet

- CommitteeReport WSRPReviewUpdateNov2016Document6 pagesCommitteeReport WSRPReviewUpdateNov2016CKNW980No ratings yet

- Judge Weatherill G C Re Kazakoff V Taft 05-04Document51 pagesJudge Weatherill G C Re Kazakoff V Taft 05-04CKNW980No ratings yet

- Site C Economics ReportDocument161 pagesSite C Economics ReportCKNW980No ratings yet

- Letter For Parents and Staff From Superintendent of Schools, February 3, 2017Document1 pageLetter For Parents and Staff From Superintendent of Schools, February 3, 2017CKNW980No ratings yet

- March 3 2017 AICDocument12 pagesMarch 3 2017 AICCKNW980No ratings yet

- Firefighters and Cancer StudyDocument24 pagesFirefighters and Cancer StudyCKNW980No ratings yet

- B.C. Ambulance ApologyDocument4 pagesB.C. Ambulance ApologyCKNW980No ratings yet

- Health Wellness SurveyDocument38 pagesHealth Wellness SurveyCKNW980No ratings yet

- Bartoli LawsuitDocument14 pagesBartoli LawsuitCKNW980No ratings yet

- NAFTA POLL - Angus Reid InstituteDocument9 pagesNAFTA POLL - Angus Reid InstituteCKNW980No ratings yet

- RCC Canadian Shopping Center Study FinalDocument33 pagesRCC Canadian Shopping Center Study FinalCKNW980No ratings yet

- 17-02 - No Charges Approved in Vancouver Police ShootingDocument10 pages17-02 - No Charges Approved in Vancouver Police Shootingpaula_global0% (1)

- Poorly Thought Out BirthdayCelebration Leads To Tickets and FinesDocument1 pagePoorly Thought Out BirthdayCelebration Leads To Tickets and FinesCKNW980No ratings yet

- MissinginAction SUN LIFE enDocument12 pagesMissinginAction SUN LIFE enCKNW980No ratings yet

- Canada Public Private 2016Document12 pagesCanada Public Private 2016CKNW980No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Supreme Court upholds interest on tax refundsDocument2 pagesSupreme Court upholds interest on tax refundsMaria Berns PepitoNo ratings yet

- Dismounting A 'Beast' LawsuitDocument6 pagesDismounting A 'Beast' LawsuitAnthony TalcottNo ratings yet

- Tex McIver Georgia Supreme Court DecisionDocument97 pagesTex McIver Georgia Supreme Court DecisionJonathan Raymond100% (2)

- Husby Forest Products Ltd. v. Jane Doe, 2018 BCSC 676Document14 pagesHusby Forest Products Ltd. v. Jane Doe, 2018 BCSC 676Andrew HudsonNo ratings yet

- Company Law Lec 3Document16 pagesCompany Law Lec 3Arif.hossen 30No ratings yet

- Mithu, Etc., Etc Vs State of Punjab Etc. Etc On 7 April, 1983Document19 pagesMithu, Etc., Etc Vs State of Punjab Etc. Etc On 7 April, 1983Mohd ShajiNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of William E. Thoresen, III, 395 F.2d 466, 1st Cir. (1968)Document3 pagesIn The Matter of William E. Thoresen, III, 395 F.2d 466, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing: Teaching MaterialDocument114 pagesLegal Writing: Teaching MaterialSulaiman CheliosNo ratings yet

- Work For Hire AgreementDocument2 pagesWork For Hire AgreementpetmartinoNo ratings yet

- 21-01-01 Samsung Opposition To Ericsson PI MotionDocument22 pages21-01-01 Samsung Opposition To Ericsson PI MotionFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- THIS RENTAL AGREEMENT Is Executed at Kolkata On This 1st Day of June, 2018 by andDocument3 pagesTHIS RENTAL AGREEMENT Is Executed at Kolkata On This 1st Day of June, 2018 by andMriganka SahaNo ratings yet

- Eric Lloyd Supreme Court OpinionDocument31 pagesEric Lloyd Supreme Court OpinionXerxes WilsonNo ratings yet

- A. Local Police Units Operating Outside Their Territorial Jurisdiction and NationalDocument10 pagesA. Local Police Units Operating Outside Their Territorial Jurisdiction and NationalShienie Marie Incio SilvaNo ratings yet

- Santiago v. Alikpala, 25 SCRA 356 (1968)Document8 pagesSantiago v. Alikpala, 25 SCRA 356 (1968)Karen Patricio LusticaNo ratings yet

- 2 PCI LEASING AND FINANCE, INC., Petitioner, vs. TROJAN METAL INDUSTRIES INCORPORATED, WALFRIDO DIZON, ELIZABETH DIZON, and JOHN DOE, Respondents.Document2 pages2 PCI LEASING AND FINANCE, INC., Petitioner, vs. TROJAN METAL INDUSTRIES INCORPORATED, WALFRIDO DIZON, ELIZABETH DIZON, and JOHN DOE, Respondents.Ken MarcaidaNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs MendozaDocument5 pagesRepublic Vs MendozaSachuzenNo ratings yet

- Legal Brief-Motion For Mandatory Judicial NoticeDocument112 pagesLegal Brief-Motion For Mandatory Judicial Noticecaljics100% (3)

- Removal of Judges in IndiaDocument2 pagesRemoval of Judges in Indiasrinath kanneboinaNo ratings yet

- US Park Police - General Order On Vehicular PursuitsDocument9 pagesUS Park Police - General Order On Vehicular PursuitsFOX 5 NewsNo ratings yet

- 03-15-2016 ECF 305 USA V JON RITZHEIMER - Response To Motion by USA As To Jon Ritzheimer Re Motion For Release From CustodyDocument12 pages03-15-2016 ECF 305 USA V JON RITZHEIMER - Response To Motion by USA As To Jon Ritzheimer Re Motion For Release From CustodyJack RyanNo ratings yet

- ObliCon Reviewer SMDocument111 pagesObliCon Reviewer SMJessa Marie BrocoyNo ratings yet

- Sonny Lo vs. KJS Eco-Formwork System Phil, Inc, GR No. 149420 (2003)Document2 pagesSonny Lo vs. KJS Eco-Formwork System Phil, Inc, GR No. 149420 (2003)Je S BeNo ratings yet

- Doa - Nep 500K - 3B KTTDocument20 pagesDoa - Nep 500K - 3B KTTmaro jerry0% (1)

- Contract of ServiceDocument3 pagesContract of ServiceBuna Lejos IndangNo ratings yet

- Fieldmens Insurance Co v. Asian Surety and Insurance CoDocument2 pagesFieldmens Insurance Co v. Asian Surety and Insurance CoMaribel Nicole LopezNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Second Impeachment of Chief Justice UnconstitutionalDocument2 pagesSupreme Court Rules Second Impeachment of Chief Justice UnconstitutionalHaelSerNo ratings yet

- Topacio Nueno v. Angeles, 76 Phil. 12Document29 pagesTopacio Nueno v. Angeles, 76 Phil. 12EmNo ratings yet

- 14 Loria VS FelixDocument2 pages14 Loria VS FelixÇhøAÿaÇhānNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Court of Appeals Manila: PetitionersDocument12 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Court of Appeals Manila: PetitionersNetweightNo ratings yet

- CONFLICT RULES ON CORP. Et - Al.Document13 pagesCONFLICT RULES ON CORP. Et - Al.RubierosseNo ratings yet