Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sws v. Comelec (Digest)

Uploaded by

ArahbellsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sws v. Comelec (Digest)

Uploaded by

ArahbellsCopyright:

Available Formats

SOCIAL WEATHER STATIONS, INCORPORATED and KAMAHALAN PUBLISHING

CORPORATION vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS

G.R. No. 147571. May 5, 2001

Facts:

SWS is a private non-stock, non-profit social research institution conducting

surveys in various fields, including economics, politics, demography, and

social development, and thereafter processing, analyzing, and publicly

reporting the results thereof. On the other hand, petitioner Kamahalan

Publishing Corporation publishes the Manila Standard, a newspaper of

general circulation, which features newsworthy items of information

including election surveys.

Petitioners brought this action for prohibition to enjoin the Commission on

Elections from enforcing 5.4 of R.A. No. 9006 (Fair Election Act), which

provides:

Surveys affecting national candidates shall not be published fifteen (15) days

before an election and surveys affecting local candidates shall not be published

seven (7) days before an election.

Election surveys refer to the measurement of opinions and perceptions of the

voters as regards a candidates popularity, qualifications, platforms or a

matter of public discussion in relation to the election, including voters

preference for candidates or publicly discussed issues during the campaign

period (hereafter referred to as Survey).

Petitioner SWS states that it wishes to conduct an election survey throughout

the period of the elections both at the national and local levels and release to

the media the results of such survey as well as publish them directly.

Petitioners argue that the restriction on the publication of election survey

results constitutes a prior restraint on the exercise of freedom of speech

without any clear and present danger to justify such restraint. They claim

that SWS and other pollsters conducted and published the results of surveys

prior to the 1992, 1995, and 1998 elections up to as close as two days before

the election day without causing confusion among the voters and that there

is neither empirical nor historical evidence to support the conclusion that

there is an immediate and inevitable danger to the voting process posed by

election surveys. They point out that no similar restriction is imposed on

politicians from explaining their opinion or on newspapers or broadcast

media from writing and publishing articles concerning political issues up to

the day of the election. Consequently, they contend that there is no reason

for ordinary voters to be denied access to the results of election surveys

which are relatively objective.

COMELEC justifies the restrictions in 5.4 of R.A. No. 9006 as necessary to

prevent the manipulation and corruption of the electoral process by

unscrupulous and erroneous surveys just before the election. It contends

that:

(1) the prohibition on the publication of election survey results during the

period proscribed by law bears a rational connection to the objective of the

law, i.e., the prevention of the debasement of the electoral process resulting

from manipulated surveys, bandwagon effect, and absence of reply;

(2) it is narrowly tailored to meet the evils sought to be prevented; and

(3) the impairment of freedom of expression is minimal, the restriction being

limited both in duration, i.e., the last 15 days before the national election and

the last 7 days before a local election, and in scope as it does not prohibit

election survey results but only require timeliness.

Ruling:

We hold that 5.4 of R.A. No. 9006 constitutes an unconstitutional abridgment

of freedom of speech, expression, and the press.

To be sure, it lays a prior restraint on freedom of speech, expression, and the

press by prohibiting the publication of election survey results affecting

candidates within the prescribed periods of fifteen (15) days immediately

preceding a national election and seven (7) days before a local election.

Because of the preferred status of the constitutional rights of speech,

expression, and the press, such a measure is vitiated by a weighty

presumption of invalidity.

For as we have pointed out in sustaining the ban on media political

advertisements, the grant of power to the COMELEC under Art. IX-C, 4 is

limited to ensuring equal opportunity, time, space, and the right to reply as

well as uniform and reasonable rates of charges for the use of such media

facilities for public information campaigns and forums among candidates.

MR. JUSTICE KAPUNAN dissents. He rejects as inappropriate the test of clear

and present danger for determining the validity of 5.4.

Instead, MR. JUSTICE KAPUNAN purports to engage in a form of balancing by

weighing and balancing the circumstances to determine whether public

interest [in free, orderly, honest, peaceful and credible elections] is served by

the regulation of the free enjoyment of the rights (page 7). After canvassing

the reasons for the prohibition, i.e., to prevent last-minute pressure on

voters, the creation of bandwagon effect to favor candidates, misinformation,

the junking of weak and losing candidates by their parties, and the form of

election cheating called dagdag-bawas and invoking the States power to

supervise media of information during the election period (pages 11-16), the

dissenting opinion simply concludes:

The dissent does not, however, show why, on balance, these considerations

should outweigh the value of freedom of expression. Instead, reliance is

placed on Art. IX-C, 4. As already stated, the purpose of Art. IX-C, 4 is to

ensure equal opportunity, time, and space and the right of reply, including

reasonable, equal rates therefor for public information campaigns and

forums among candidates. Hence the validity of the ban on media

advertising.

What test should then be employed to determine the constitutional validity

of 5.4? The United States Supreme Court, through Chief Justice Warren, held

in United States v. OBrien:

A government regulation is sufficiently justified

[1] if it is within the constitutional power of the Government;

[2] if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest;

[3] if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free

expression; and

[4] if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms [of

speech, expression and press] is no greater than is essential to the

furtherance of that interest.]

This is so far the most influential test for distinguishing content-based from

content-neutral regulations and is said to have become canonical in the

review of such laws.

Under this test, even if a law furthers an important or substantial

governmental interest, it should be invalidated if such governmental interest

is not unrelated to the suppression of free expression. Moreover, even if the

purpose is unrelated to the suppression of free speech, the law should

nevertheless be invalidated if the restriction on freedom of expression is

greater than is necessary to achieve the governmental purpose in question.

To summarize, we hold that 5.4 is invalid because (1) it imposes a prior

restraint on the freedom of expression, (2) it is a direct and total suppression

of a category of expression even though such suppression is only for a

limited period, and (3) the governmental interest sought to be promoted can

be achieved by means other than the suppression of freedom of expression.

You might also like

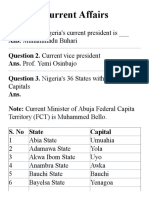

- Nigeria Current AffairsDocument36 pagesNigeria Current Affairsonatade oyinloluwaNo ratings yet

- SWS and Pulse Asia Vs Comelec Case DigestDocument3 pagesSWS and Pulse Asia Vs Comelec Case DigestYna Johanne100% (2)

- SOCIAL WEATHER STATIONS, INC. vs. COMELEC - 2015 POLIDocument2 pagesSOCIAL WEATHER STATIONS, INC. vs. COMELEC - 2015 POLIHadjie Lim100% (1)

- Churchill v. Rafferty PDFDocument3 pagesChurchill v. Rafferty PDFAntonio Rebosa0% (1)

- People V ManriquezDocument2 pagesPeople V ManriquezistefifayNo ratings yet

- 40 - Consti2-People V Cayat GR L-45987 - DigestDocument2 pages40 - Consti2-People V Cayat GR L-45987 - DigestOjie SantillanNo ratings yet

- Remigio Vs SandiganbayanDocument5 pagesRemigio Vs SandiganbayanArahbells67% (3)

- Carbonilla vs. Board of Airlines RepresentativesDocument1 pageCarbonilla vs. Board of Airlines RepresentativesArahbells100% (2)

- NJ-03 Polling ResultsDocument17 pagesNJ-03 Polling ResultsconstantiniNo ratings yet

- Social Weather Station v. Comelec Restriction On Freedom of ExpressionDocument2 pagesSocial Weather Station v. Comelec Restriction On Freedom of ExpressionRoward100% (2)

- Digest SWS Versus ComelecDocument2 pagesDigest SWS Versus ComelecAileenJane Mallonga100% (1)

- Gamboa v. CruzDocument2 pagesGamboa v. Cruzd2015memberNo ratings yet

- Fonacier Vs CADocument1 pageFonacier Vs CAMACNo ratings yet

- Callejo, SR., J.: Writ of Habeas Corpus When Writ Not AllowedDocument3 pagesCallejo, SR., J.: Writ of Habeas Corpus When Writ Not AllowedRion MargateNo ratings yet

- Philippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Document3 pagesPhilippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Marienyl Joan Lopez VergaraNo ratings yet

- GMA Netwaork v. COMELEC (Digest)Document2 pagesGMA Netwaork v. COMELEC (Digest)Arahbells100% (1)

- Dumlao v. Comelec, 95 Scra 392Document3 pagesDumlao v. Comelec, 95 Scra 392RowardNo ratings yet

- 19 Galvez v. CA 237 SCRA 685Document2 pages19 Galvez v. CA 237 SCRA 685Zepht BadillaNo ratings yet

- Borjal vs. CADocument3 pagesBorjal vs. CAJm Santos100% (1)

- Ang Tibay V CIRDocument2 pagesAng Tibay V CIRSultan Kudarat State University100% (2)

- People V Nitafan 207 Scra 726Document1 pagePeople V Nitafan 207 Scra 726MylesNo ratings yet

- People v. Fajardo (GR No. L-12172 Aug 29, 1958)Document2 pagesPeople v. Fajardo (GR No. L-12172 Aug 29, 1958)Ei BinNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST: Legaspi Vs Civil Serv. CommDocument3 pagesCASE DIGEST: Legaspi Vs Civil Serv. CommKIM COLLEEN MIRABUENANo ratings yet

- Tieng v. Palacio-Alaras, G.R. Nos. 164845, 181732 & 185315Document1 pageTieng v. Palacio-Alaras, G.R. Nos. 164845, 181732 & 185315Mac Jan Emil De OcaNo ratings yet

- Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Petition (Digests From Various Websites)Document66 pagesFreedom of Expression, Assembly and Petition (Digests From Various Websites)ejusdem generisNo ratings yet

- Lozano V Martinez Case DigestDocument2 pagesLozano V Martinez Case DigestThea Barte100% (1)

- Sanidad VS ComelecDocument2 pagesSanidad VS ComelecRuss Tuazon100% (1)

- Chavez V Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesChavez V Comelec DigestkristinevillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Cantwell v. Connecticut 310 U.S. 296 May 20, 1940Document3 pagesCantwell v. Connecticut 310 U.S. 296 May 20, 1940Edwin VillaNo ratings yet

- Borjal v. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageBorjal v. Court of AppealsErikaNo ratings yet

- MTRCB V Abs-Cbn (GR 155282)Document1 pageMTRCB V Abs-Cbn (GR 155282)scartoneros_1No ratings yet

- 01 Ichong v. Hernandez (G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957) PDFDocument2 pages01 Ichong v. Hernandez (G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957) PDFChristine Casidsid67% (3)

- VILLAR V TIP CDDocument2 pagesVILLAR V TIP CDheloiseglaoNo ratings yet

- Pamil v. Teleron (Digest)Document2 pagesPamil v. Teleron (Digest)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Fonacier vs. CA (96 Phil. 417 (1955) )Document2 pagesFonacier vs. CA (96 Phil. 417 (1955) )Mary Angeline Gurion100% (1)

- Feeder International v. CADocument1 pageFeeder International v. CAPaul Joshua Torda Suba100% (1)

- Magoncia Vs PalacioDocument2 pagesMagoncia Vs PalacioElvin Salindo100% (3)

- Comelec VS TagleDocument1 pageComelec VS TagleISULAN BFP 12No ratings yet

- Dela Cruz V People - Case DigestDocument2 pagesDela Cruz V People - Case DigestAbigail TolabingNo ratings yet

- Lozano vs. MartinezDocument2 pagesLozano vs. MartinezMichelle Montenegro - Araujo100% (1)

- CONSTI2 - MTRCB v. ABS-CBNDocument2 pagesCONSTI2 - MTRCB v. ABS-CBNdelayinggratificationNo ratings yet

- BAYAN Vs ERMITADocument2 pagesBAYAN Vs ERMITACeresjudicataNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument1 pageCase DigestShiela BrownNo ratings yet

- Taruc v. de La Cruz (G.R. No. 144801, March 10, 2005) Case DigestDocument3 pagesTaruc v. de La Cruz (G.R. No. 144801, March 10, 2005) Case DigestCarlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corp. v. Comelec Restrictions On Freedom of ExpressionDocument2 pagesABS-CBN Broadcasting Corp. v. Comelec Restrictions On Freedom of ExpressionRoward100% (1)

- De Los Santos v. MallareDocument2 pagesDe Los Santos v. MallareTasneem C BalindongNo ratings yet

- People v. Malmstedt - Case DigestDocument4 pagesPeople v. Malmstedt - Case DigestRobeh AtudNo ratings yet

- Anonymous VDocument5 pagesAnonymous VEnav LucuddaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 139465Document1 pageG.R. No. 139465RizzaNo ratings yet

- People Vs O'cochlain (Hijacking)Document10 pagesPeople Vs O'cochlain (Hijacking)JimNo ratings yet

- People v. Fajardo, 104 SCRA 443Document2 pagesPeople v. Fajardo, 104 SCRA 443Dominique VasalloNo ratings yet

- People V. Malngan G.R. No. 170470, Sep 26, 2006Document3 pagesPeople V. Malngan G.R. No. 170470, Sep 26, 2006Jamiah Obillo HulipasNo ratings yet

- Osmena v. COMELECDocument3 pagesOsmena v. COMELECRaymond RoqueNo ratings yet

- Go v. CA G.R. No. 101837, February 11, 1992: FactsDocument3 pagesGo v. CA G.R. No. 101837, February 11, 1992: FactsJoseph John Santos RonquilloNo ratings yet

- COrdero V CabatuandoDocument1 pageCOrdero V CabatuandoPrincess AyomaNo ratings yet

- Taruc V Dela CruzDocument1 pageTaruc V Dela CruzAiza Giltendez0% (1)

- Adiong Vs Comelec Case DigestDocument2 pagesAdiong Vs Comelec Case DigestEbbe Dy100% (1)

- Legaspi v. Civil Service CommissionDocument2 pagesLegaspi v. Civil Service CommissionButch Sui GenerisNo ratings yet

- Case Digest CalingasanDocument4 pagesCase Digest CalingasanAce EspañoNo ratings yet

- Ayer Productions VS CapulongDocument2 pagesAyer Productions VS CapulongAlyssa Mae Ogao-ogaoNo ratings yet

- Dissent of Justice LeonenDocument17 pagesDissent of Justice LeonenLhem NavalNo ratings yet

- Social Weather Station, Inc. v. Commission On Elections (357 SCRA 496)Document6 pagesSocial Weather Station, Inc. v. Commission On Elections (357 SCRA 496)Jomarc MalicdemNo ratings yet

- Petitioners RespondentDocument27 pagesPetitioners RespondentAlfredMendozaNo ratings yet

- SWS V ComelecDocument11 pagesSWS V ComelecRuby TorresNo ratings yet

- Lagman v. MedialdeaDocument4 pagesLagman v. MedialdeaArahbellsNo ratings yet

- NPC v. The Provincial Treasurer of BenguetDocument2 pagesNPC v. The Provincial Treasurer of BenguetArahbells100% (3)

- Guingona v. CaragueDocument2 pagesGuingona v. CaragueArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Petron v. TiangcoDocument1 pagePetron v. TiangcoArahbells100% (1)

- Valley Trading Co v. CFI of IsabelaDocument1 pageValley Trading Co v. CFI of IsabelaArahbells100% (2)

- Republic Vs Sunlife Assurance Co. of CanadaDocument1 pageRepublic Vs Sunlife Assurance Co. of CanadaArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Province of Bulacan v. CA, GR 126232Document1 pageProvince of Bulacan v. CA, GR 126232ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- City of Manila Vs Coca-Cola Bottlers Phils.Document3 pagesCity of Manila Vs Coca-Cola Bottlers Phils.Arahbells100% (2)

- PBA vs. CADocument1 pagePBA vs. CAArahbellsNo ratings yet

- The New Government Accounting System ManualDocument37 pagesThe New Government Accounting System ManualArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Substantial EvidenceDocument15 pagesSubstantial EvidenceArahbells100% (1)

- What Is The Reason For According Greater Protection To Employees? Explain. 2. What Is Bonus?Document22 pagesWhat Is The Reason For According Greater Protection To Employees? Explain. 2. What Is Bonus?ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Dizon Vs Posadas JRDocument1 pageDizon Vs Posadas JRArahbells100% (1)

- Wells Fargo vs. CIR, 70 Phil. 505Document1 pageWells Fargo vs. CIR, 70 Phil. 505ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- OptDocument2 pagesOptArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations Cases Listed in The SyllabusDocument6 pagesLabor Relations Cases Listed in The SyllabusArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Domondon Taxation Notes 2010Document80 pagesDomondon Taxation Notes 2010ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Mercado Vs NLRCDocument17 pagesMercado Vs NLRCArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Mercado Vs AMA Computer CollegeDocument59 pagesMercado Vs AMA Computer CollegeArahbellsNo ratings yet

- 1984 - G.R. No. L-39999, (1984-05-31)Document10 pages1984 - G.R. No. L-39999, (1984-05-31)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Matling Vs CorosDocument11 pagesMatling Vs CorosArahbellsNo ratings yet

- 2000 - G.R. No. 90828, (2000-09-05)Document12 pages2000 - G.R. No. 90828, (2000-09-05)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- 2003 - G.R. No. 145804, (2003-02-06)Document6 pages2003 - G.R. No. 145804, (2003-02-06)ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Substantial EvidenceDocument2 pagesSubstantial EvidenceArahbells100% (1)

- BP - Batas Pambansa Blg. 68Document52 pagesBP - Batas Pambansa Blg. 68ArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Adayof Remembrance: Splost A Go in Dekalb CountyDocument20 pagesAdayof Remembrance: Splost A Go in Dekalb CountyDonna S. SeayNo ratings yet

- Tanada V Cuenco G.R. No. L-10520Document1 pageTanada V Cuenco G.R. No. L-10520April Toledo67% (3)

- AP Gov Ch. 9 NotesDocument3 pagesAP Gov Ch. 9 NotesAnaNo ratings yet

- 2005 11 04 - DR1amended3Document2 pages2005 11 04 - DR1amended3Zach EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Lok Sabha ArunDocument2 pagesLok Sabha ArunHuzaifa SalimNo ratings yet

- Vol 6 Issue 47 - March 22-28, 2014Document38 pagesVol 6 Issue 47 - March 22-28, 2014Thesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- Election Cases Moya Vs Del FierroDocument7 pagesElection Cases Moya Vs Del FierroAkiko AbadNo ratings yet

- Learn Grammar Rules Through Editorial Everyday at 7Pm: The Hindu Editorial Analysis With VocabularyDocument23 pagesLearn Grammar Rules Through Editorial Everyday at 7Pm: The Hindu Editorial Analysis With VocabularyKinjal KapadiaNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 06-04-2013Document32 pagesTimes Leader 06-04-2013The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- VadrumDocument108 pagesVadrumamru56No ratings yet

- Case Digest For Dec. 17Document3 pagesCase Digest For Dec. 17CLARISSE ILAGANNo ratings yet

- Rules of Procedure Election Contests MTCDocument16 pagesRules of Procedure Election Contests MTCCL DelabahanNo ratings yet

- Elec 2Document121 pagesElec 2manumaraNo ratings yet

- Form 6: Application For Inclusion of Name in Electoral RollDocument5 pagesForm 6: Application For Inclusion of Name in Electoral RollSaurav HalderNo ratings yet

- Mpa 209 RecallDocument11 pagesMpa 209 RecallArantxa Stefi Leyva SantosNo ratings yet

- Bagabuyo Vs COMELECDocument3 pagesBagabuyo Vs COMELEC上原クリスNo ratings yet

- Brooke's Point, PalawanDocument2 pagesBrooke's Point, PalawanSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- SSLTR 2 PMRe Naming Madurai AirportDocument2 pagesSSLTR 2 PMRe Naming Madurai AirportPGurusNo ratings yet

- History Topic: The History of VotingDocument3 pagesHistory Topic: The History of VotingVitor FébrusNo ratings yet

- NCR - PaterosDocument4 pagesNCR - PaterosireneNo ratings yet

- Americanpageantchapter11 PDFDocument22 pagesAmericanpageantchapter11 PDFBella WhiteNo ratings yet

- HIST 300 - Module 2 - Section 1 - Essay Question 1Document2 pagesHIST 300 - Module 2 - Section 1 - Essay Question 1Berrak GüloğluNo ratings yet

- Notice of Obama ID Forgery and Fraud Sent To Loretta LynchDocument181 pagesNotice of Obama ID Forgery and Fraud Sent To Loretta LynchSyndicated NewsNo ratings yet

- Constitution YBPDocument14 pagesConstitution YBPAsh Hykal100% (2)

- CH 5 Interest Aggregation and Political PartiesDocument9 pagesCH 5 Interest Aggregation and Political PartiesLö Räine AñascoNo ratings yet

- Lectures On DemocracyDocument60 pagesLectures On DemocracymanhioNo ratings yet

- Order Finn V Cobb County Board ElectionsDocument34 pagesOrder Finn V Cobb County Board ElectionsLindsey BasyeNo ratings yet

- Stephanie Clifford v. Donald Trump Et Al Amended ComplaintDocument41 pagesStephanie Clifford v. Donald Trump Et Al Amended ComplaintDoug Mataconis100% (1)